Abstract

This study examined attitudes and perspectives of 34 health service providers through in-depth interviews in the Republic of Georgia who encountered an injection drug-using woman at least once in the past two months. Most participants’ concept of drug dependence treatment was detoxification, as medication-assisted therapy was considered part of harm reduction, although it was thought to have relatively better treatment outcomes compared to detoxification. Respondents reported that drug dependence in women is much more severe than in men. They also expressed less tolerance towards drug-using women, as most providers view such women as failures as a good mother, wife, or child. Georgian women are twice stigmatized, once by a society that views them as fulfilling only a limited purposeful role and again by their male drug-using counterparts. Further, the vast majority of respondents were unaware of the availability of specific types of drug-treatment services in their city, and even more did not seek connections with other service providers, indicating a lack of linkages between drug-related and other services. The need for women-specific services and a comprehensive network of service linkages for all patients in drug treatment is critical. These public health issues require immediate consideration by policy makers, and swift action to address them.

Keywords: injection drug use, Republic of Georgia, service providers, stigma, women

It is estimated that Georgia has 40,000 adult “problem drug users” (systematic users of hard and/or injecting drugs) (Sirbiladze 2010) of whom approximately 2,000–3,000 are women. This estimate is likely quite conservative, because needle exchange programs and other nongovernmental organizations in the region report that most injection drug-using women are neither in treatment nor in harm reduction services. Routinely collected data show that females compose 1% to 5% of drug-related service beneficiaries in Georgia (Javakhishvili et al. 2006; Javakhishvili & Sturua 2009).

HIV prevalence is less than 0.1% in the general population and between 1% to 4% among the drug-using population in Georgia (Government of Georgia 2010). Prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is estimated to be 58% among the injection drug-using population (Curatio International Foundation & Public Union Bemoni 2009; Government of Georgia 2010; Javakhishvili et al. 2011). Several surveys have reported that needle-sharing rates among female drug users are as much as twice those of rates among males (Curatio International Foundation & Public Union Bemoni 2009). Together, these data indicate a high level of injecting equipment and paraphernalia sharing among injection drug-using adults, especially women. These data also strongly suggest that the low HIV prevalence does not reflect the drug-risk environment. Moreover, these higher equipment-sharing rates may reflect a power differential favoring male dominance, leading to women’s particular vulnerability to HIV and HCV infection and underscoring the need for women-centred drug treatment in Georgia.

Injection drug-using women are one of the most hidden and underserved groups in Georgia (Javakhishvili et al. 2011). Publicly-funded substance abuse treatment is not readily available in the country, limiting the access of indigent injection drug-using adults to treatment. Women face additional barriers to treatment, including the absence of women-specific drug treatment services. In most drug treatment and harm reduction programs, the majority of clients are middle-aged men. Most such programs rarely have women counselors, and the male counselors may be ill-equipped to be address women’s specific problems, and lack sensitivity to the unique needs and challenges that injection drug-using women face in their daily lives (Curatio International Foundation & Public Union Bemoni 2009; Burns 2009; Javakhishvili et al. 2011).

In one regional study women were less likely than men to seek treatment or attend harm reduction services, which increased their reliance on male partners for access to clean needles and syringes (Burns 2009). Low motivation and denial, social stigma and labelling, lack of trust, unreliable treatment, and the absence of comprehensive treatment services were commonly identified as barriers that limited access to treatment (Copeland 1997; Jessup et al. 2003; Smith & Marshall 2007). Previous research has also found that fear of losing custody of their children and the possibility of detection of substance use were identified as important barriers that prevented drug-using women from accessing general health care services (Smith & Marshall 2007).

Various drug abuse treatment modalities such as detoxification, medication-assisted therapy (methadone and buprenorphine), and harm reduction programs are available in Georgia. Harm reduction services are relatively well developed and include voluntary HIV counselling and testing, needle and syringe programs, condom distribution, medical consultations, and case management (Javakhishvili et al. 2006). Many substance abuse treatment providers share a drug-free orientation to treatment. Traditionally, substance abuse treatment in Georgia has been restricted to detoxification, without subsequent psychosocial rehabilitation, due to the limited availability of psychosocial counselling. Accordingly, the relapse rate following two-week detoxification was high (Javakhishvili & Sturua 2009). More recently, medication-assisted treatment with opioid agonists has been rapidly scaled up and has accounted for more than 2/3 of all treatment episodes in 2010 (Javakhishvili et al. 2011).

Empirical data on drug use by women in the Republic of Georgia are scarce. No research has examined the factors that motivate injection drug-using women to seek health care and the barriers they encounter when they do. Moreover, there is no research examining factors that may encourage or inhibit the disclosure of substance use to health service providers by women in Georgia. The purpose of the present study was to examine the attitudes, beliefs, and practice of health service providers in Georgia that influence demand for and access to treatment by women with substance use problems.

METHODS

Procedure

A qualitative study was conducted from May to September 2011 among health care providers in three cities in the Republic of Georgia: Tbilisi, Gori, and Zugdidi. These cities were selected to provide diversity in city size (e.g., Tbilisi, Zugdidi and Gori are estimated to have 1,152,500, 75,900 and 49,500 inhabitants, respectively) and geographic representation. A purposive sampling method was used to select health care providers who had encountered an injection drug-using woman at least once in the past two months. The research project utilized a Community Advisory Board (CAB), composed of eleven health care providers for women, and a Beneficial Advisory Board (BAB) comprised of four drug-using women to select a sample of health service providers. Collaboration with the CAB and BAB yielded a comprehensive listing of all treatment settings and locations that encounter injection drug-using women in Tbilisi, Gori, and Zugdidi (n = 17). Using this list, several providers in each treatment setting were selected to represent a diverse range of services and types of health service professionals: nurses, physicians, psychologists, social workers, addiction specialists, methadone maintenance providers, and other drug treatment-related professionals. Research staff contacted the prospective participants nominated by the CAB and BAB by phone or in person and briefly described the study. Research staff assessed eligibility and briefly described the study procedures to eligible participants. Study-eligible and interested candidates set an appointment time for the staff to consent and interview them at a mutually convenient and private location.

Institutional Review Board Approval for this study was obtained from the Office of Research Protection Institutional Review Board at RTI International, USA and from the Maternal and Child Care Union, Georgia.

Participants

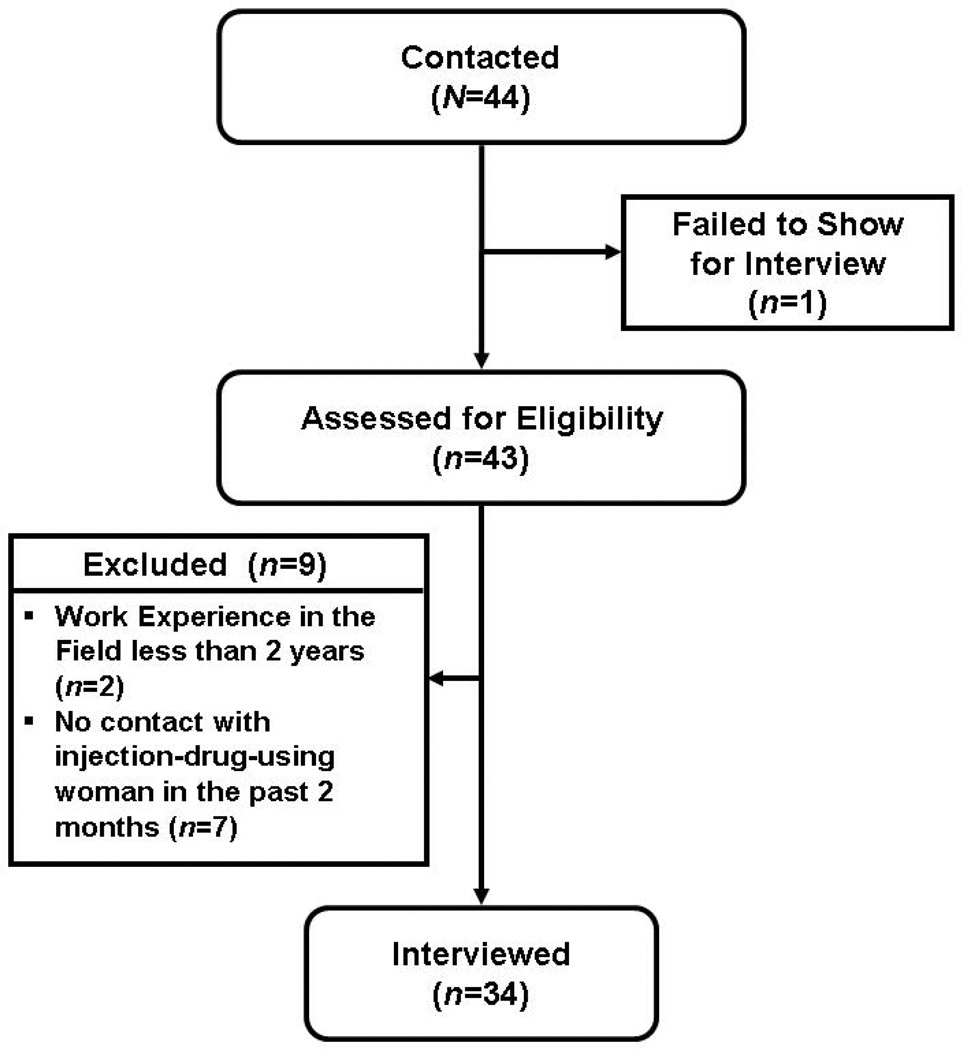

A total sample of 44 health service providers was contacted. Of these 44, one did not show up for an initial assessment, and nine were determined to be ineligible to participate, leaving a final sample of 34 (see Figure 1). In-depth interviews were conducted with these 34 health service providers. In terms of respondents’ specialisation and professional affiliation the sample was fairly diverse: physicians, psychologists, nurses, and drug counsellors working in addiction clinics, harm reduction programs and general health care settings (see Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow Chart for Recruitment of Service Providers

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Working Area of Health Service Providers (N = 34)

| N (%) | M (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Males | 10 (29%) | ||

| Females | 24 (71%) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Georgian | 34 (100%) | ||

| Age | 42.6 (9.9) | ||

| Years of education | 17.0 (1.4) | ||

| Highest Degree | |||

| MD | 22 (65%) | ||

| Bachelor | 6 (18%) | ||

| PhD | 4 (12%) | ||

| Nurse | 2 (6%) | ||

| Working area | |||

| Addiction treatment (including residential and medication-assisted) | 15 (44%) | ||

| Low-threshold services (including psycho-social rehabilitation, voluntary counseling and testing, needle and syringe programs) | 8 (24%) | ||

| Cardiologist, neurologist and internal medicine specialist | 4 (12%) | ||

| Rehabilitation field (plasmopheresis, physiotherapy, and massage) | 3 (9%) | ||

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 2 (6%) | ||

| Infectious diseases treatment | 1 (3%) | ||

| Intensive therapy (anesthesiologist) | 1 (3%) |

It is important to note that the professional community treating addiction disorders in Georgia is quite small. Therefore, in order to protect the identities of the participants, no demographic information accompanies the quotations found in the Results.

Interviews

Individual in-depth interviews lasted approximately 60 minutes and were administered by experienced interviewers in Georgian. The interview covered four main topics: (1) questions about the respondents’ clinical practice, (2) respondents’ perspectives on the roles of women and men in Georgian society, (3) respondents’ perceptions of drug use and addiction treatment, and (4) respondents’ thoughts about the current drug addiction treatment system in Georgia. All interviews were audio-recorded following the written consent of the participant.

Qualitative Analysis

These digital audio files were transcribed directly into Georgian in Unicode text format, in preparation for analysis. Resulting transcripts were exported as pdf files that were then imported directly into nVivo 9 (http://www.qsrinternational.com/products_nvivo.aspx) qualitative data analysis software, followed by a content and thematic analysis. The analytic process involved searching the text for themes, which were coded, examined, and collected together to form categories. The analysis was driven by research questions and objectives defined at the outset of the research. These a priori questions provide a theoretical framework within which themes could be grouped and synthesized to create typologies and provide explanations.

RESULTS

Participants

Basic information about study participants can be found in Table 1. A little less than one third (30%) were males. Participants, all of whom were Georgian, varied widely in terms of age (range 23–62 years old), and were generally highly educated (range 14–20 years of education completed).

Barriers to Being in Treatment or Receiving Services

Providers shared the belief that there was both a lack of services and a lack of diversity of services. Demand for services such as needle and syringe programs, rehabilitation, shelters, crisis centers is high, but these services are not available in most cities in Georgia. Methadone maintenance programs are well developed and geographical coverage is high; however, service providers reported that there are still empty treatment slots, which suggests that other barriers to entry, including stigma, may exist or demand for methadone maintenance may be low.

Based on unofficial figures, available harm reduction services are insufficient. The existing kinds of services are also insufficient.

… there are not so many options as for example in Tbilisi. There are not lot choices in Tbilisi too, but you know if we compare …

Low appeal in the substitution therapy program is a real problem and we plan to find out the reasons by conducting a survey … in order to identify the barriers holding male and female patients from participation in the substitution therapy program.

Moreover, there is a lack of information regarding medication-assisted therapy among health care representatives. Evidence-based information is sometimes lacking and myths about methadone still dominate. This situation provokes societal misunderstanding and may partially explain why medication-assisted therapy has not rapidly expanded in Georgia.

Because there are myths in our society, not only among users, but among general society and I have heard it even from the medical personnel, not from the methadone-related personnel, from surgeons, general physicians … That methadone kills! And imagine what would a relative of a drug user feel when he hears it from a doctor?

Outcome Measurements of Successful Treatment

There was no consensus among the providers about what was a successful outcome of treatment for drug dependence. None of the respondents provided indicators for treatment effectiveness, although a combination of all stages of treatment and modalities starting from detoxification or opioid-agonist treatment followed by long-term psychotherapy and rehabilitation were often described as effective approaches. Almost all respondents shared a drug and medication abstinence orientation to treatment, as being both drug and medication-free were seen as a desired outcome of a treatment. At the same time, opioid-agonist treatment was well accepted and considered to be an effective intervention.

Basically I support detoxification with its long-term rehabilitation …

First of all, when we start treatment through detoxification, and not only detox, in a substitution program as well … treatment shall necessarily be accompanied by psychotherapy and approach from the church … and treatment gets more effective …

I can say it as a narcologist … There are some candidates who need, definitely need this methadone or suboxone program, but it should be in a small number … others should get treatment in clinics.

Service Providers’ Vision of Drug-Using Women and Drug-Using Men

The vast majority of service providers consider that drug dependence and its related health consequences in women are more severe than in men. In terms of treatment outcome the viewpoint of service providers falls in two opposing camps—some view treatment outcomes for women as likely to be more positive than for men, while others take the opposite view, but also demonstrate some sensitivity about the complexity in treating women.

In terms of perspective if a woman ends up in a safe social environment she has a better perspective then men.

I guess it is more effective among men than among women … as far as I know …

This disease is very complicated among women and it is very difficult to cure them, to make them aware, to take them out of this condition … You have to work with them a lot … It is far more complicated if compared with men …They are less open …

Women become degraded very fast.

If a woman started to use the drug because of her young age or due to some trauma, there is a more chance for her to get the curing.

Based on the practical experience of service providers, drug-using females constitute about 2% to 30% of their beneficiaries, with 10% to 15% indicated by providers in most cases.

In order to better understand differences in the perception of substance-using women and men on the part of health service providers, they were asked to provide three adjectives or phrases to separately describe drug-using women and men. Results of this exercise are presented in Table 2. The information contained in this table is both quite simple to see and quite profound. First, the only positive adjective used by the service providers to describe substance-using women was “pretty.” Second, there are a number of negative descriptors that serve both for men and women, notably: liars, irresponsible, aggressive, and self-centered. The only positive adjective to describe both men and women was “intellectual.” Third, there are a number of descriptors that are unique to substance-using women, including: hysterical, unstable, and pitiful. And, there are several adjectives or phrases that serve to describe men but not women, most notably: psychopath, cunning, and rude.

TABLE 2.

Adjectives or Phrases Health Service Providers Used to Describe Drug-Using Women and Men

| Women | Men | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quote | Number | Adjective of Phrase | Number | Quote |

| 6 | liar | 6 | ||

| “She loves to lie…” | “They’re liars too; unreliable people.” | |||

| 5 | irresponsible | 9 | ||

| “They are all irresponsible…” | “…they also lack sense of responsibility…” | |||

| 2 | aggressive | 4 | ||

| “Aggressive, agitated and liars.” | “…aggressive. I think men are more aggressive.” | |||

| 2 | selfish | 2 | ||

| “…does not care about other people…” | “…irresponsible and selfish, sponger.” | |||

| 2 | impudent | 1 | ||

| “They are cynical, they behave impudently…” | “…some of them are impudent…” | |||

| 2 | egoist | 4 | ||

| “Egocentrism; lack of criticism and inclination to aggravation…” | “Egocentrism is the dominant trait…” | |||

| 3 | lack criticism | 3 | ||

| “…lacking self-criticism.” | ||||

| 3 | agitated | 0 | ||

| “Agitated, hesitating, stubborn and not self-established.” | ||||

| 2 | anxious | 3 | ||

| “Over-emotional, anxious and unbalanced.” | “…in constant panic and fearing tomorrow and not having drugs…” | |||

| 3 | untidy | 3 | ||

| “Quite pretty looking, but untidy…” | “…they can be untidy, just like women users…” | |||

| 3 | apathetic | 3 | ||

| “Apathy…untidiness…” | ||||

| 2 | miserable | 1 | ||

| “Miserable, sorrowful and not self-fulfilled.” | “…ill-bred and others are miserable…” | |||

| 2 | weak | 1 | ||

| “She is a weak person and might be influenced by others easily…” | “…what else… weak-willed…” | |||

| 1 | not self-realized | 2 | ||

| “…a non-realized woman, who could realize herself in the field of drugs only…” | “They are not self-realized…” | |||

| 1 | intellectual | 1 | ||

| “…and intellectual even…” | “Intellectuals mostly, a bit irresponsible…” | |||

| 1 | hopeless | 1 | ||

| “…women are particularly hopeless, pessimist.” | “…unfortunate, but still determined; Somehow hopeless…” | |||

| 1 | lack willpower | 1 | ||

| “…the lack of willpower is another characteristic.” | ||||

| 1 | withdrawn | 1 | ||

| “Second, they are withdrawn…” | “And the third is secluded.” | |||

| 1 | disillusioned | 1 | ||

| “…they have wrong views, have illusions…” | “…miserable and… disappointed or disillusioned…” | |||

| 1 | shameless | 1 | ||

| “Shameless, dull and without interests…” | “Rude, untidy, and shameless.” | |||

| 2 | stubborn | 0 | ||

| “…stubborn, pig-headed” | ||||

| 4 | hysterical | 0 | ||

| “She is very hysterical…” | ||||

| 3 | unstable | 1 | ||

| “…ones I have dealt with are psychologically unstable…” | “…emotionally unstable.” | |||

| 2 | not future focused | 0 | ||

| “…the person does not think about future…not result-oriented.” | ||||

| 3 | pretty | 0 | ||

| “Pretty, yes, pretty…” | ||||

| 2 | unfortunate | 0 | ||

| “…unfortunately, but in reality, unfortunate.” | ||||

| 4 | pitiful | 0 | ||

| “She’s a pitiful, struggling person…” | ||||

| 2 | bold | 0 | ||

| “…and they are too bold.” | ||||

| 0 | psychopath | 3 | ||

| “Psychopath…often explosive…” | ||||

| 0 | cunning | 3 | ||

| “…they are also cunning…very cunning persons…” | ||||

| 0 | rude | 3 | ||

| “Rude, he is rude in general…” | ||||

| 0 | aimless | 3 | ||

| “…they are aimless.” | ||||

| 1 | thin | 2 | ||

| “Skinny, all of them…” | “…they are really skinny and somewhat aggressive…” | |||

| 0 | idle | 2 | ||

| “Idler…I think this is the best word.” | ||||

| 0 | lost | 2 | ||

| “Light-minded, lost and permanently anxious.” | ||||

Note. Number refers to the number of health service providers who provided such an adjective or phrase.

Barriers to Life Satisfaction for Drug-Using Women: Drug-Using Male Partners

Almost all service providers viewed male partners as introducing women to drug use and also obstructing drug-using women from seeking treatment, support or help. Women drug users were viewed as lacking the necessary skills to support themselves and being fully dependent on their male partners.

It depends on many external factors, first of all always, or in 90% of cases, when a woman is a drug user … their sexual partners or husbands were also drug users, who were the first to let them try it.

It is a hidden one, because, … if a woman starts to use drugs it means that she had some reason for that…either because of some man, or because of a father, or a son … because of somebody. That’s why this system does not need to treat such a woman. That’s why there is considerably low number of visits.

Partners are major obstacles … because she has her own surroundings, where she had to stay on a daily basis … drug user husband, his friends and …

There are a lot of barriers. For example, revelation of their status; they want to quit but depend on someone, they could turn out to be violence victims, and leaving this circle is really hard. If they could change it, they would do it probably, but as far as I see, not many of them want it. There are a lot of barriers since they often do not know where to go, whom to talk to.

Barriers to Life Satisfaction for Drug-Using Women: Vulnerability to Violence

The majority of service providers share the idea that drug-using women are more vulnerable to violence than nondrug-using women. They could be victims of violence from their family members, partner and friends.

Surely the drug-using women find themselves in risky situations more often than nonusers. If we compare ten women not using drugs, who are the victims of violence and ten drug-using women with potential exposure to any kind of violence, the latter group is much more vulnerable anyway.

Violence has become an ordinary thing for them. For example, I know a drug addict woman that says that her partner beating her up is not violence, since it has turned into a routine. Another one said she was beaten up with the foot in her stomach and said it’s nothing.

I don’t think the types of violence differ from each other, but I think frequency and intensiveness does, since drug user women become victims of violence even more.

Yes, the level of violence against them is very high … From the part of family and also from the society in general.

Barriers to Treatment for Drug-Using Women: Stigma

Respondents suggested that due to stigma and fear of disclosure women drug users never talk about their drug use with health care providers. Georgian women generally do not seek adequate medical care and, therefore, it is not surprising that female drug users often avoid visiting a doctor, and especially receiving drug-related services due to the fact that confidentiality and anonymity can be breached. Some service providers talked about cases in which service providers disclosed confidentiality.

Well, there were cases, maybe I shouldn’t say it, but there were cases when doctors refused their patients’ medical services after patients told them about their [drug] problem.

When a woman joins the substitution therapy program or turns for treatment, for instance when she says she’s a substance addict, this means that she had stepped over many things before she came to us.

Georgian society often prescribes and proscribes behavioral “norms” and attitudes towards women and men. The vast majority of respondents pointed out that a drug-using woman is less tolerated and more stigmatized than a nondrug-using woman. Indeed, Georgian women are twice stigmatized: once by a society, including service providers, that views them as fulfilling only a limited purposeful role, and again by their male drug-using counterparts. They are viewed as failed mothers, wives or daughters, and as less acceptable compared with a man.

Daughter drug user is less acceptable for parents than boy drug users.

Well … I am not sure … probably she would still fail to go [for treatment], because public opinion is very important for her … and staff of this program [substitution therapy] is also a part of the society, is not it? I mean we need to work a lot in this direction to change a level of consciousness of the society in the first place …

A female drug user is a heavier burden for the family than a male user.

Female drug users first of all encounter stigma and discrimination on behalf of the society and male drug users, as we’ve already mentioned, not to mention doctors.

This is quite a stigmatized group, even twice more stigmatized than group of the men users. Even the drug user men themselves do not perceive these women as … full-fledged members of the society.

Barriers to Treatment for Drug-Using Women: Health Care Providers are in Need of Training Regarding the Illness and Treatment of Drug Addiction

It should be noted that other than drug-related medical care personnel, health care providers are not ready to provide adequate health service to drug-using women, due to lack of information, lack of skills and lack of knowledge on how to treat a drug-dependent person with their own unique sets of health conditions.

The only thing I can notice—there are some pricks, or scars, and if I ask them where these scars and cicatrices come from, they would answer that they had some accidents in their childhood ….

Even if I notice! They would tell me that they had done blood transfusion after some infection! The only thing which is really distinguishable, that they have cicatrices on their stomach and hands … many of them have … both men and women, so this is a direct; indicator for me, but when I ask them, they say that they had some accidents in their childhood … or they got drunk the other day and … they are trying to get rid of you …

I don’t want to say it’s more superficial treatment, but drug user women become subjects to criticism …Yes, probably. If her status were revealed a woman disclosing her drug user status would be treated less adequately and in an undesirable manner.

Drug-Using Women, Pregnancy, and Childbirth: Lack of Knowledge

Most respondents pointed out that there is no measurement and evaluation tools for the pregnant drug-using woman and Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS), so drug-dependent neonates almost never receive appropriate treatment. Drug-using pregnant women are often advised to undergo an abortion, because of fears around the possible unhealthy development of the fetus related to illicit substance use. Participants who were physicians stated that medical guidelines and protocols for opioid-agonist treatment of opioid-dependent pregnant women and NAS are urgently needed.

If she gets pregnant, that’s another issue. There is almost no service for adequate supervision and patronage for pregnant drug user women.

Well, if this problem is revealed by women and if gynecologists can, they will always advise it [abortion] …They say that pregnancy will be complicated; a child would be inferior, etc.… I cannot say they treat them badly, but there is a doubt about her perspectives as a parent, and her possibilities to adequately look after children.…

If they know that a child is born to a drug user they do not know what to do, at least in regions … none of the doctors would realize what to do if the child is born with abstinence syndrome, and may not realize what it means if the child is anxious, unless a mother discloses her status.

Need for Women-Focused Services

There was consensus among health care providers regarding the need for specialized treatment programs for women; however, the components and systems for such treatment were not specified.

I would probably do a separate site for women only. Not sure why, but this would be better. Not that men and women would go together, but where women would attend separately.

Well … it should be a house for women having difficult life conditions. This is how I would call it. I would not call it the house for drug user women. A rehabilitation center … something like a crisis center … with psychological rehabilitation, for example detox, substitution therapy … some kind of a complex approach. I think it would be better in terms of violence.

Although endorsement of such a viewpoint was not universal among the service providers:

Ah, gynecologist and dentist—that’s for women separately and they can go to other services and institutions. It’s incorrect to have separate services for drug user women. I think it’s not correct. But I think there should be some kind of educational work … for example, she would also be told what to do if she gets pregnant, that infections are transmitted through blood and that these infections can be transferred to fetus. I would teach what to do, I would educate more.

DISCUSSION

This study examines the attitudes and perspectives of health service providers (drug related and nondrug-related) towards factors that may influence treatment-seeking behavior of women with substance use problems in Georgia. Several major issues were identified which can be used to shape directions for interventions, public policy discussions and future research.

Opportunity to Provide Education and Training about the Illness and Treatment of Addiction

Findings from the in-depth interviews suggest that health care providers would benefit from the opportunity to receive additional education and training regarding the best methods for confidentially and empathetically screening, assessing and referring drug-addicted patients for treatment that would also include sensitivity training about the context of women’s lives. Further, health care professionals working in addiction treatment may also benefit from the development of national drug treatment guidelines which would provide a stated consensus on what effective treatment is and how its success should be measured, and what role each modality of treatment plays in the recovery of the addicted patient.

Women Drug-Users are Twice Stigmatized, Creating the Context for Restricted Access and Utilization of Health Care Services, Including Addiction Treatment

Overall, the quotes from health care providers, both within and outside of drug treatment, illustrated how society more severely stigmatizes women than men for drug use. According to the health care providers, this stigmatization of drug-using women is also held among drug-using men. To a large extent stigmatization of drug-using women appears to be driven by the belief that they are failed daughters, mothers, wives, and human beings in general. Drug-using women are seen by providers to be irresponsible, unreliable, pitiful, liars and hysterical. They are viewed as unskilled and unable (and/or unwilling) to support themselves, and highly dependent on their (often drug-using) partners. This double stigma from the society and from drug-using males negatively influences drug-using females’ self worth, creates a context that is highly vulnerable to discrimination, neglect and violence (emotional, physical and sexual). Together, these forces create an environment in which drug-using women rarely trust anyone from whom they might seek help and support. Therefore, it is not surprising that they are rarely, if ever, willing to disclose their drug use and associated problems, and are reluctant to discuss the violence they experience.

In addition to the treatment barriers related to stigma, there are also structural barriers. These structural barriers include the fact that most drug treatment services are provided by private and nongovernmental organizations and, as such, are limited in terms of number of beneficiaries they can serve, as they depend on donor organizations. There are five methadone-maintenance treatment sites that are fully free for beneficiaries, as these programs are funded by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. There are presently 11 state cofunded methadone-maintenance programs in which participants have to cover part of the costs, and not all drug-dependent individuals can bear the treatment cost, which is about US$80 per month in terms of patient copay (the average monthly Georgian salary in 2009 was approximately US$350). Most respondents mentioned that this cost-related barrier primarily adversely impacted drug-using women, as most of them are not able to pay for their own treatment due to financial dependency on someone (mostly on their male partner). Inpatient detoxification clinics provide two-week detoxification and payment for this short-term treatment is about US$1200. There are limited possibilities to undergo detoxification free of charge—the Georgian government covers treatment for some limited number (80–100) of patients per year (Chikovani et al. 2010).

Further, the potential barrier of a breach of confidentiality is an extremely important issue in the case of agonist-medication maintenance treatment services. Programs cannot guarantee full anonymity due to a strict drug enforcement policy and agonist medication regulations in Georgia. All methadone maintenance treatment programs require ID cards from patients to receive services, and this registry of patients who are in methadone maintenance treatment is something that strongly discourages potential patients from entering treatment. It has been suggested that as a result of this registration, methadone slots are not filled in regional centres providing methadone maintenance treatment, while at times when methadone maintenance treatment was initiated in 2005–2006, there were waiting lists for such programs (Otiashvili, Sárosi & Somogyi 2008). Harm reduction programs do not require ID cards, and injection drug-using adults view them as more or less trustworthy and acceptable.

These perceptions and current barriers underscore the importance and need for interventions focusing on internal and external barrier reduction for women. Interventions for drug-using women should include life and health skills building and educating women to become independent and self-confident in decision-making and life planning. If any reforms are to be planned in relation to female drug users’ services, promoting a sensitive, nonjudgmental and empathetic approach to this patient population must be a priority and should be considered as an indispensable precondition for any further interventions.

Lack of Integrated Care Approach

Study results suggest that there is a complete disconnect among the various health services that might deal with females who use drugs at different stages of their addiction, comorbidity, and lifespan. The vast majority of health service providers are not aware of the existing drug abuse-related services in their cities and are unable to provide appropriate referrals for patients in need. There is clearly an opportunity for the development of a comprehensive network of services, which if published and provided to all health care providers, could enhance their ability to make relevant referrals. It should be mentioned that in many instances appropriate referrals and initiation of specialized treatment depend on the high cost of such services and the inability of drug-using patients to bear those costs.

Limitations

Like all studies, there are limitations to be noted. First, the sampling approach was purposive and not random. Thus, it may not be fully representative of service providers. Furthermore, the data are based on self-reports provided during in-depth interviews, which creates a potential threat to the validity of these findings. However, to minimize this threat participants were guaranteed confidentiality and individual face-to-face interviews were conducted. Respondents were free to respond to or skip any questions. Finally, we do not know to what extent our findings generalize to other cities in Georgia or elsewhere.

In conclusion, health care providers provide a unique look into the strengths and opportunities for further improving the treatment approach for women drug-users in the Republic of Georgia. The need for empathetic, confidential and nonjudgmental women-specific services and a comprehensive network of service linkages for all patients in drug treatment are central issues for advancing the drug treatment policy in Georgia.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIDA grant R01 DA029880. The authors thank Marina Chavchanidze, Natia Topuria, Mariam Chelidze, Lika Kirtadze, Lile Batselashvili, and Mariam Sinjikashvili for conducting and transcribing interviews.

REFERENCES

- Burns K. Women, Harm Reduction, and HIV: Key Findings from Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Ukraine. New York: International Harm Reduction Development Program of the Open Society Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chikovani I, Chkartishvili N, Gabunia T, Tabatadze M, Gotsadze G. Document for Country Coordination Mechanism. 2010. HIV/AIDS Situation and National Response Analysis: Priorities for the NSPA 2011–l2016. Available at http://ungeorgia.ge/userfiles/files/GEO%20HIV-AIDS%20NSPA%202011-1016.%20Eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland J. A qualitative study of barriers to formal treatment among women who self-managed change in addictive behaviours. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1997;14(2):183–190. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(96)00108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curatio International Foundation & Public Union Bemoni. Study report. Tbilisi, Georgia: 2009. Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Surveys Among Injecting Drug Users in Georgia (Tbilisi, Batumi, Zugdidi, Telavi, Gori, 2008–2009) Available at http://bemonidrug.org.ge/userfiles/files/Kvlevebi/EN/Bio-behavioral%20surveillance%20surveys%20among%20injecting%20drug%20use.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Georgia. UNGASS Country Progress Report, Reporting Period 2008 – 2009 Calendar Years. 2010 Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/knowyourresponse/countryprogressreports/2010countries/georgia_2010_country_progress_report_en.pdf.

- Javakhishvili J, Sturua L. Drug Situation in Georgia - 2008. Southern Caucasus Anti-Drug Programme. Tbilisi, Georgia: Southern Caucasus Anti-Drug Programme; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Javakhishvili DJ, Sturua L, Otiashvili D, Kirtadze I, Zabransky T. Overview of the drug situation in Georgia. Adictologie. 2011;11(1):42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Javakhishvili J, Kariauli D, Lejava G, Stvilia K, Todadze K, Tsintsadze M. Drug Situation in Georgia - 2005. Tbilisi, Georgia: Southern Caucasus Anti-Drug Programme; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jessup MA, Humphreys JC, Brindis CD, Lee KA. Extrinsic barriers to substance abuse treatment among pregnant drug dependent women. Journal of Drug Issues. 2003;33(2):285–304. [Google Scholar]

- Otiashvili D, Sárosi P, Somogyi G. The Beckley Foundation Drug Policy Program Briefing Paper Fifteen. London: The Beckley Foundation; 2008. Drug Control in Georgia: Drug Testing and the Reduction of Drug Use? [Google Scholar]

- Sirbiladze T. Estimating the Prevalence of Injection Drug Use in Georgia: Concensus Report. Tbilisi: Bemoni Public Union; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Smith FM, Marshall LA. Barriers to effective drug addiction treatment for women involved in street-level prostitution: A qualitative investigation. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health (CBMH) 2007;17(3):163–170. doi: 10.1002/cbm.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]