Significance

Asset price bubbles are an important example of human group decision making gone awry, but the behavioral and neural underpinnings of bubble dynamics remain mysterious. In multisubject markets determined by 11–23 subjects, with 2–3 subjects simultaneously scanned using functional MRI, we show how behavior and brain activity interact during bubbles. Nucleus accumbens (NAcc) activity tracks the price bubble and predicts future price changes. Traders who buy more aggressively based on NAcc signals earn less. High-earning traders have early warning signals in the anterior insular cortex before prices reach a peak, and sell coincidently with that signal, precipitating the crash. These experiments could help understand other cases in which human groups badly miscompute the value of actions or events.

Keywords: neuroeconomics, asset bubbles, hyperscanning

Abstract

Groups of humans routinely misassign value to complex future events, especially in settings involving the exchange of resources. If properly structured, experimental markets can act as excellent probes of human group-level valuation mechanisms during pathological overvaluations—price bubbles. The connection between the behavioral and neural underpinnings of such phenomena has been absent, in part due to a lack of enabling technology. We used a multisubject functional MRI paradigm to measure neural activity in human subjects participating in experimental asset markets in which endogenous price bubbles formed and crashed. Although many ideas exist about how and why such bubbles may form and how to identify them, our experiment provided a window on the connection between neural responses and behavioral acts (buying and selling) that created the bubbles. We show that aggregate neural activity in the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) tracks the price bubble and that NAcc activity aggregated within a market predicts future price changes and crashes. Furthermore, the lowest-earning subjects express a stronger tendency to buy as a function of measured NAcc activity. Conversely, we report a signal in the anterior insular cortex in the highest earners that precedes the impending price peak, is associated with a higher propensity to sell in high earners, and that may represent a neural early warning signal in these subjects. Such markets could be a model system to understand neural and behavior mechanisms in other settings where emergent group-level activity exhibits mistaken belief or valuation.

Asset price bubbles are extended periods in which prices rise well above fundamental values. Identifying bubbles and predicting crashes from price data alone is a notoriously difficult problem (1). However, prices are created by the collective behavior of the market participants, so neural activity could offer biomarkers for the evolution of price bubbles. Studies of asset price bubbles indicate a role for psychological factors such as “euphoria” (2), “irrational exuberance” (3), “mania” (4), “animal spirits” (5), and “sentiment” (6). We sought neural data supporting such psychological constructs that might help to identify price bubbles.

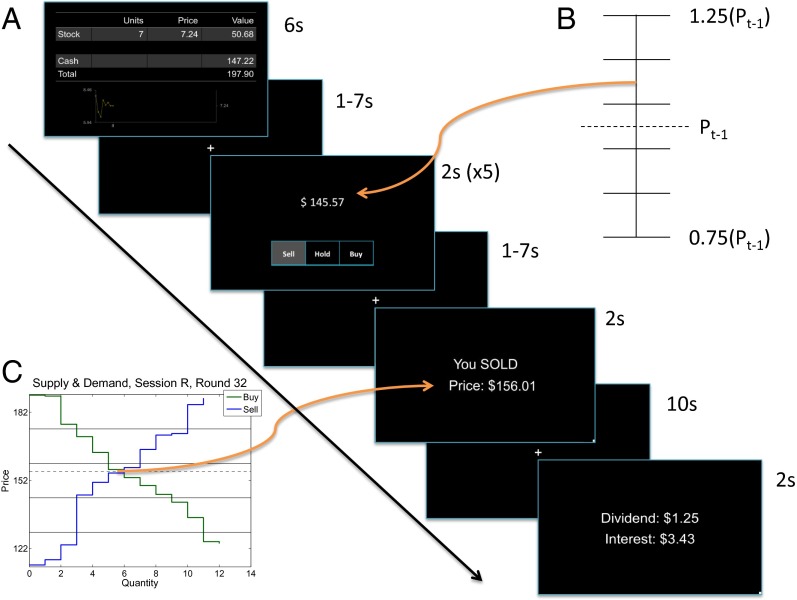

We observed the formation and crash of endogenous bubbles in experimental asset markets (7, 8) using multisubject neuroimaging. In each of 16 market sessions, consisting of an average of 20 traders (range, 11–23), we measured the neural activity of 2–3 participants (n = 44 total) using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Our market design is based upon ref. 9. Traders could buy or sell one risky asset unit in each period. Fig. 1A illustrates the sequence of experimental events. Each market had 50 trading periods. All subjects began with 100 units of experimental currency (a risk-free asset) and 6 units of a risky asset. Each period, the risky asset paid a currency dividend d of either 0.40 or 1.00 per unit (with equal probability), creating an expected dividend E[d] = 0.70. Currency earned a fixed interest rate r of 5% each period. After all 50 rounds of trading were completed, the risky asset was redeemed for 14 units of the risk-free currency.

Fig. 1.

Asset market experiment. (A) Each period subjects viewed the following screens, in order: Positions, Order Entry (×5), Trading Results, and Dividends and Interest. (B) Order elicitation procedure. Subjects responded Buy, Sell, or Hold to a random (uniform) price draw from each of five bins, each of width equal to 10% of the last period’s price. The middle bin was centered on the last period’s price. (C) How the price is chosen (=market clearing). The highest price at which subjects responded Buy, and the lowest price at which subjects responded Sell, were entered into a closed book call market. Prices and trading outcomes were reported on the Trading Results screen.

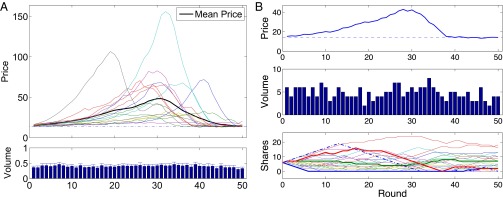

These parameters defined an unambiguous fundamental value for the risky asset. Buying the risky asset in period t at price Pt and selling it one period later leads to the expected net gain . The same investment of Pt in the risk-free asset yields a sure net gain of rPt. If these two amounts are equal—in economic terms, if asset prices are “in equilibrium”—then there is a stationary price equal to a constant fundamental value F defined by . Prices persistently above F = 14 indicate a bubble; such a clear bubble measure is rarely available in field data. Fig. 2A illustrates the price paths for all 16 markets in this experiment. Bubbles are typical and large: the median price peak was 64.30 (range, 19.68–156.01). The bubble paths always result in a crash, and prices in the final period are near the fundamental F = 14 (median, 14.13). Fig. 2B illustrates a typical experimental session. This market bubble crashed after period 30. Trading volume is substantial, which means that prices do not result from a few extreme traders.

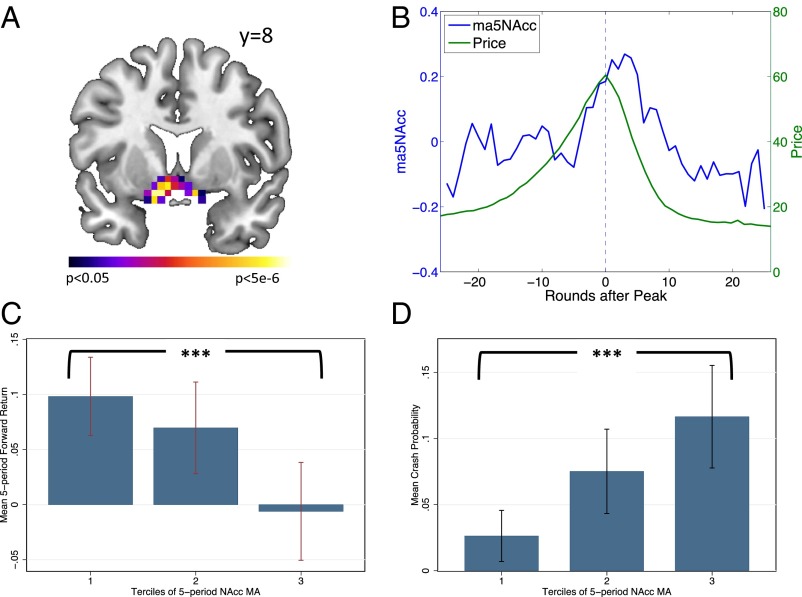

Fig. 2.

Endogenous market bubbles. (A) Price paths in16 different experimental market sessions. The dark line shows the average price in each period over the 16 sessions. Plotted below the prices is the normalized per-subject volume for each period; error bars are SEs. (B) Single-session prices (Top) and trading volume (Middle) from one statistically typical experimental session. At Bottom is shown the risky asset holdings; each subject is indicated by a different color. MRI subjects are shown with thicker lines. The dashed line is the “clairvoyant” profit-maximizing share path (assuming subjects could somehow correctly anticipate all future prices).

Results

A key computation during the asset market experiment involves the monitoring of round-to-round trading activity. Using a general linear model (GLM) of the blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal of neural activity, we first established that the ventral striatum, including the nucleus accumbens (NAcc), responds strongly to both buying and selling outcomes revealed at the “Trading Results” screen (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Table S4). In the call market mechanism that we use, subjects trade only when the market clearing price is below their expressed maximum willingness to buy (best bid), or is above their expressed minimum willingness to sell (best offer). Because the market price is unknown when the orders are placed, any trade therefore results in a positive reward prediction error. The NAcc receives a high density of projections from midbrain dopamine neurons, which are known to encode reward prediction error signals (10). Therefore, these GLM results are consistent with hundreds of studies that indicate that the NAcc plays a central role in the encoding of reinforcement, subjective value, and reward (11–13) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B).

Fig. 3.

Irrational exuberance. (A) GLM results showing the conjunction of neural responses to “You Bought” and “You Sold” messages; P < 0.05 (familywise error corrected). Peak T = 7.69, MNI = [−10, 8, −14]. (B) Average NAcc activity tracks the endogenous market bubble. MA5Nacc (blue) is the average of the five previous periods’ NAcc activity, recentered around the maximal (peak) price in each session. (C) NAcc activity predicts future returns of the risky asset. Earners were divided into three groups, by terciles of earnings. Each bar shows the mean five-period forward return, for each tercile of the five-period moving average of NAcc activity, calculated within session. The mean return in the highest tercile of NAcc activity is significantly less than the mean return in the lowest tercile. (D) NAcc activity within session predicts crashes. Each bar shows the relative frequency of a crash (defined as a price drop of greater than 50%) occurring in the next five periods. The observed incidence of crashes is much greater in the highest tercile of our moving-average NAcc activity signal.

To connect the temporal dynamics of neural activity to the valuation dynamics reflected in the market price, we extracted trial-to-trial BOLD signal responses to the “Trading Results” screen (which shows both prices and bought-or-sold information) in a region of interest (ROI) centered on the bilateral NAcc [Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) [±12, 8, −8]; see SI Appendix, Fig. S2A]. Recent studies have suggested a role for the NAcc in the evaluation of both states and policies (14), and we hypothesized that the time series of neural activity in the NAcc would contain information about the current state of the market (15). To test this hypothesis, we realigned neural and behavioral data from all of the sessions on a common timescale with 0 marking the peak price in each session. We then averaged the BOLD signal in our NAcc ROI across all subjects and then computed the moving average of the previous five periods of aggregate NAcc activity. The resulting moving-average NAcc time series is associated with the current level of the endogenous price bubble (Fig. 3B).

We next investigated whether neural activity in the NAcc could signal future price changes within a given market session. To do so, we calculated the five-period moving-average NAcc signal (as described above) within each session, and sorted this measure into three terciles. For each tercile of our market-level measure of NAcc activity, we computed the mean of the five-period forward return, . Fig. 3C shows a clear and statistically significant difference between forward returns in the lowest tercile and forward returns in the highest tercile, with high values of NAcc activity associated with the lowest returns (P < 0.001, Mann–Whitney/Wilcoxon rank sum test for equality of distributions). Furthermore, Fig. 3D shows that when the within-session NAcc moving average is high, the empirical probability of a crash (defined as a drop of more than 50% in price over the next five trading rounds) is more than four times greater than when it is low (0.117 vs. 0.026; baseline, 0.075; P < 0.001, Fisher’s exact test). Within the context of these experiments, neural activity in the NAcc appears to predict future changes in the price of the risky asset. Lower levels of NAcc activity are associated with higher future returns and low likelihood of a crash, whereas higher levels of NAcc activity are associated with low future returns and increased likelihood of a crash.

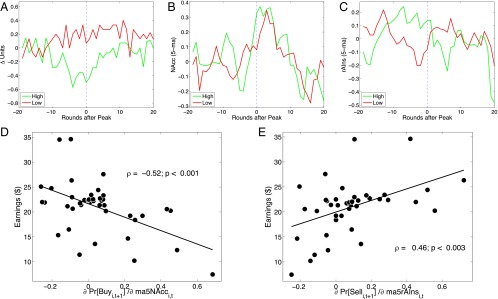

Many finance theories of bubbles describe mixtures of naïve backward-looking “momentum” investors, fundamental traders, and sophisticated investors who plan ahead (16–18). When bubbles form and crash, these three types will have low, medium, and high earnings, respectively. To investigate the relationship between individual task performance and neural activity, we sorted all subjects into three terciles of experimental earnings. These groups clearly have different patterns of dynamic share trading (Fig. 4A). However, Fig. 4B shows that the moving-average NAcc time series in the highest and lowest-earning groups are similar across trading periods.

Fig. 4.

Individual differences: high and low earners and neurobehavioral metrics. (A) Trading behavior of the highest and lowest earnings terciles, aligned around the market peaks. The y axis plots the mean change in units of the risky asset in each period. These trading curves cross about 10 periods before the peak of the market. The high earners’ sell-off continues unabated until about 10 periods after the peak. (B) The NAcc activity association of prices appears to be consistent across subject groups. The colored lines plot the mean NAcc activity in the highest and lowest terciles of the payout distribution. (C) Average right anterior insula activity in high earners and low earners shows that low earner activity fluctuates around 0, whereas high earner activity shows a peak that coincides with the beginning of the sell-off of units shown in A (5–10 periods before the price peak). We used an ROI centered on MNI [36, 24, 2], corresponding to the peak “risk prediction” signal from ref. 23. (D) The cost of changing one’s buying probability as a function of the change in activity in the NAcc as read out by earnings. Forty-one scanned subjects are included in this plot. The negative slope shows that tracking the group-defined bubble and committing to it in the form of increased brain-to-buying probability costs money. This defines a neural metric for irrational exuberance and measures it in terms of earnings. (E) Increased propensity to sell based on right anterior insula activity (a neurobehavioral brain-selling relation) is associated with higher earnings. The positive slope shows that subjects whose insula activity is predictive of future selling earn more.

Because average NAcc signal dynamics are similar in these two groups, but earnings performances are so different, we looked for an association across individuals between their NAcc-buying sensitivity and performance. For each trader, we computed via logistic regression, where is the probability of buying at time t + 1 and Nt is the average NAcc activity at time t over the five periods from t − 4 to t. The partial derivative is a brain-buying signal: it measures the change in propensity to buy as a function of recent NAcc activity. Fig. 4C plots individual trader profits against . The relation is significantly negative (ρ = −0.52, P < 0.001). The negative slope measures the economic cost of “following one’s nucleus accumbens.”

We also used interval regression analysis to estimate the independent contribution of neural activity in several ROIs to future valuation (SI Appendix). We find that the NAcc response is positively associated with demand for the risky asset in subsequent trading periods, after controlling for observable variables such as returns, dividend yield, and the individual’s current policy (SI Appendix, Table S7). This pattern appears to be driven by a stronger brain–behavior link in low-earning subjects.

Although low earners are net buyers around the price peak, high earners begin to sell their shares a few periods before the bubble peak (Fig. 4A). To investigate the neural activity associated with the switch to selling before the peak, we focused a priori on the anterior insular cortex. The insula is an “interoceptive” area that is active during bodily discomfort and unpleasant emotional states, such as pain, anxiety, and disgust. Its anterior region is thought to be associated with the awareness of bodily states (19, 20). Anterior insula is also activated by financial risk (21, 22) and by variance in prediction errors, a measure of uncertainty in temporal-difference learning models (23). We hypothesized that neural activity in the anterior insula might motivate sophisticated participants to begin selling the risky asset. Fig. 4D shows the average BOLD activity paths from the anterior insular cortices of the high- and low-earnings groups (using an ROI centered at MNI [36, 24, 2], radius of 6 mm, based on ref. 21; SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Near the time that the two groups begin their respective shifts to selling and buying, insula activity increases in the high earners but there is no similar response in the low earners.

Analogously to the previous NAcc-buying sensitivity analysis, we measured the association between the insula-selling relationship and performance. Fig. 4E plots total earnings against , where is the probability of selling at time t + 1, and It is the average neural activity in the right anterior insula at time t over the previous five periods (including time t). This measure of the neural brain-selling link is positively correlated with performance (ρ = 0.46, P < 0.003). In the high earners, the right anterior insula signal seems to encode a risk detection or warning signal that is associated with selling profitably.

Discussion

The experimental method is ideal for understanding the neuropsychology of asset bubbles, because the experimenter can control the fundamental asset value, and hence clearly identify when prices are too high (1–3, 18, 24, 25). Our experimental design used live trading to show that asset price bubbles result endogenously from interactions between different types of traders. Traders react to buy or sell events and represent bubble magnitude commonly in the NAcc [also observed in other investment decision tasks (26–28)]. Elevated NAcc activity is associated with low future returns and higher likelihood of a crash. Therefore, NAcc activity in our experiments appears to provide an indicator for price bubbles that is consistent with historical accounts of euphoria and irrational exuberance near the peak in prices.

Traders who buy more aggressively given NAcc signals perform worse in the task. The slope of this buy/NAcc relation represents a new “neurobehavioral metric” for the financial cost of “irrational exuberance” and could be used as quantitative and parametric biomarker in other contexts where humans overvalue bad acts or outcomes like compulsive gambling, overeating, or drug addiction (29).

Another neurobehavioral finding is a positive association between trading performance and selling when neural activity in the anterior insula is elevated. The insula signal may reflect increased perception of risk (21–23) or of uncomfortable bodily states (19, 20). The presence of an elevated insula signal in the high earners before the price peak, its concurrent absence in the low earners, its association with trading pattern changes, and the stronger neurobehavioral insula-selling link among high earners suggest that increased neural activity in the right anterior insula may constitute an early warning signal for these individuals to begin switching from the risky to the risk-free asset. The evidence from both of our neurobehavioral metrics is consistent with the study by Kuhnen and Knutson (26), who show that activations in both of these regions can lead to shifts in risk preferences.

Many theories of bubbles in large natural markets depend on economic agents’ incentives (30) or on market structure (31). A recent literature examines the interaction between valuation and media coverage (32–34). Another explanation involves traders who get internal signals (or “hunches”) that a bubble exists; bubbles then persist because traders who get early signals keep buying, expecting that the other traders’ signals will not arrive until later (35). However, these theories do not specify neural mechanisms (36). Our evidence is consistent with bubble accounts based on bounded rationality, emotion, and neural activity (2–9, 16–18, 36, 37). Warren Buffet famously said, “Be fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful.” Our experimental results support the first part of his advice to a surprising degree: Wiser traders who begin selling when their insula is active (indicating discomfort) sell a few periods before the peak to traders with the highest “greed,” measured by increased NAcc-buying sensitivity.

Our results contribute to understanding the biological basis of group valuation in natural asset markets. Modern examples of bubbles in the last three decades include stocks in Japan, in China, and in the US high-tech sector, and housing in many countries. Bubbles redistribute enormous wealth and can leave long-lasting macroeconomic scars, and are therefore important to both investors and policymakers. In 1996, Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan asked: “But how do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values?” (38). His successor, Ben Bernanke, suggested “progress will require careful empirical research with attention to psychological as well as economic factors” (39). Our results point in the direction of theories based on an interaction between traders with exuberant valuation and forward-looking traders who ride bubbles, and then sell when they feel uncertain.

Materials and Methods

We conducted 16 experiment sessions (2 in October 2011, 8 in January 2012, and 6 in April 2012) with 320 total subjects. Each session included between 11 and 23 subjects (mean, 20; min, 11; max, 23). The majority of our subjects (276 total) were University of California, Los Angeles, students participating in the experiment at the California Social Science Experimental Laboratory (CASSEL). In addition, 2–3 individuals per session (44 total) took part in the experiment from two locations at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute (Blacksburg and Roanoke, VA). These subjects underwent fMRI of their neural activity during the experiment. All participants were networked together via a special experiment software package, NEMO, to conduct the experiment. NEMO was designed for use with multiple subjects in the scanner.

Of the 44 total subjects we scanned, 2 subjects were dropped because of technical issues with syncing behavioral and functional imaging data. One additional subject was dropped because the subject had no “Sell” transactions, leaving 41 fMRI subjects.

Behavior-only participants received a $5 show-up payment, whereas subjects who underwent fMRI scanning received an additional payment of $50. Before trading began, the experimenters read the instructions aloud. Subjects then took a five-question quiz (reproduced below), after which the experimenters reviewed the quiz answers. In addition, subjects participated in three practice trading rounds before live trading began.

SI Appendix, Table S1, provides summary statistics separately for subjects who did and did not undergo imaging. We also conducted one pilot session where all subjects (behavior-only and fMRI) were located in Virginia; this session is included in the data. Our scanned subjects are in general older (mean age, 28.43 vs. 23.15). In addition, 85% of our scanned population indicated their race as White or Hispanic, whereas 70% of our behavior-only subjects indicated that their race was Asian. The sex balance for both groups is close to 50%.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Nathan Apple for help implementing the large group experiment across three cities and four sites simultaneously. We also thank Antonio Rangel for contributions to the early stages of this project. This research was supported by National Science Foundation Grant SES-00-99209, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Lipper Family Foundation (C.F.C.), National Institutes of Health Grants DA11723 and MH085496 (to P.R.M.), The Kane Family Foundation (P.R.M.), Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (P.R.M.), and a Wellcome Trust Principal Research Fellowship (to P.R.M.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1318416111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Flood RP, Garber PM. Market fundamentals versus price-level bubbles: The first tests. J Polit Econ. 1980;88(4):745–770. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kindleberger CP, Aliber RZ. Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shiller R. Irrational Exuberance. 2nd Ed. New York: Broadway Books; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ofek E, Richardson M. Dotcom mania: The rise and fall of internet stock prices. J Finance. 2003;58(3):1113–1138. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akerlof G, Shiller R. Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism. Princeton: Princeton Univ Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker M, Wurgler J. Investor sentiment and the cross-section of stock returns. J Finance. 2006;61(4):1645–1680. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plott CR, Sunder S. Rational expectations and the aggregation of diverse information in laboratory security markets. Econometrica. 1988;56(5):1085–1118. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith VL, Suchanek GL, Williams AW. Bubbles, crashes, and endogenous expectations in experimental spot asset markets. Econometrica. 1988;56(5):1119–1151. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bostian AJ, Holt CA. Price bubbles with discounting: A Web-based classroom experiment. J Econ Educ. 2009;40(1):27–37. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montague PR, Dayan P, Sejnowski TJ. A framework for mesencephalic dopamine systems based on predictive Hebbian learning. J Neurosci. 1996;16(5):1936–1947. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01936.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montague PR, Hyman SE, Cohen JD. Computational roles for dopamine in behavioural control. Nature. 2004;431(7010):760–767. doi: 10.1038/nature03015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yarkoni T, Poldrack RA, Nichols TE, Van Essen DC, Wager TD. Large-scale automated synthesis of human functional neuroimaging data. Nat Methods. 2011;8(8):665–670. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartra O, McGuire JT, Kable JW. The valuation system: A coordinate-based meta-analysis of BOLD fMRI experiments examining neural correlates of subjective value. Neuroimage. 2013;76:412–427. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.02.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J, Daw ND. Signals in human striatum are appropriate for policy update rather than value prediction. J Neurosci. 2011;31(14):5504–5511. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6316-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kishida KT, et al. Sub-second dopamine detection in human striatum. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23291. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shleifer A. Inefficient Markets. Oxford: Oxford Univ Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barberis N, Greenwood R, Jin L, Shleifer A (2013) X-CAPM: An extrapolative capital asset pricing model. NBER Working Paper (National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA), No. 19189.

- 18.Haruvy E, Noussair CN. The effect of short selling on bubbles and crashes in experimental spot asset markets. J Finance. 2006;61(3):1119–1157. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Critchley HD, Wiens S, Rotshtein P, Öhman A, Dolan RJ. Neural systems supporting interoceptive awareness. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(2):189–195. doi: 10.1038/nn1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Craig AD. How do you feel—now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(1):59–70. doi: 10.1038/nrn2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Preuschoff K, Bossaerts P, Quartz SR. Neural differentiation of expected reward and risk in human subcortical structures. Neuron. 2006;51(3):381–390. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohr PN, Biele G, Heekeren HR. Neural processing of risk. J Neurosci. 2010;30(19):6613–6619. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0003-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Preuschoff K, Quartz SR, Bossaerts P. Human insula activation reflects risk prediction errors as well as risk. J Neurosci. 2008;28(11):2745–2752. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4286-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Camerer C, Weigelt K. In: Double Auction Markets. Friedman D, Rust J, editors. Redwood City, CA: Addison-Wesley; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dufwenberg M, Lindqvist T, Moore E. Bubbles and experience: An experiment. Am Econ Rev. 2005;95(5):1731–1737. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuhnen CM, Knutson B. The neural basis of financial risk taking. Neuron. 2005;47(5):763–770. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lohrenz T, McCabe K, Camerer CF, Montague PR. Neural signature of fictive learning signals in a sequential investment task. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(22):9493–9498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608842104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Martino B, O’Doherty JP, Ray D, Bossaerts P, Camerer C. In the mind of the market: Theory of mind biases value computation during financial bubbles. Neuron. 2013;79(6):1222–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brewer JA, Potenza MN. The neurobiology and genetics of impulse control disorders: Relationships to drug addictions. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75(1):63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen F, Gorton G. Churning bubbles. Rev Econ Stud. 1993;60(4):813–836. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hong H, Scheinkman J, Xiong W. Asset float and speculative bubbles. J Finance. 2006;61:1073–1117. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dyck A, Zingales L. The bubble and the media. In: Cornelius P, Kogut B, editors. Corporate Governance and Capital Flows in a Global Economy. Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Veldkamp L. Media frenzies in markets for financial information. Am Econ Rev. 2006;96(3):577–601. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhattacharya U, Galpin N, Ray R, Yu X. The role of the media in the Internet IPO bubble. J Financ Quant Anal. 2009;44(3):657–682. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abreu D, Brunnermeier M. Bubbles and crashes. Econometrica. 2003;71(1):173–204. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lo A. Fear, greed, and financial crises: A cognitive neurosciences perspective. In: Fouque JP, Langsam J, editors. Handbook on Systemic Risk. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shefrin H. Beyond Greed and Fear. Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenspan A. 1996. The Challenge of Central Banking in a Democratic Society. Available at www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/1996/19961205.htm. Accessed June 12, 2014.

- 39.Bernanke B. 2010. Implications of the Financial Crisis for Economics. Available at www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20100924a.htm. Accessed June 12, 2014.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.