Significance

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy along with molecular dynamics simulation is shown to be a useful tool for understanding drug binding to therapeutic proteins. Herein, the selective binding of felodipine to human Aurora A kinase is employed as a test system to demonstrate this powerful technique. Preliminary knowledge of the protein structure makes this approach robust for drug discovery.

Keywords: vibrational spectroscopy, structure–activity relationship, ligand binding

Abstract

We demonstrate the use of surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) as an excellent tool for identifying the binding site of small molecules on a therapeutically important protein. As an example, we show the specific binding of the common antihypertension drug felodipine to the oncogenic Aurora A kinase protein via hydrogen bonding interactions with Tyr-212 residue to specifically inhibit its activity. Based on SERS studies, molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation, biochemical assays, and point mutation-based validation, we demonstrate the surface-binding mode of this molecule in two similar hydrophobic pockets in the Aurora A kinase. These binding pockets comprise the same unique hydrophobic patches that may aid in distinguishing human Aurora A versus human Aurora B kinase in vivo. The application of SERS to identify the specific interactions between small molecules and therapeutically important proteins by differentiating competitive and noncompetitive inhibition demonstrates its ability as a complementary technique. We also present felodipine as a specific inhibitor for oncogenic Aurora A kinase. Felodipine retards the rate of tumor progression in a xenografted nude mice model. This study reveals a potential surface pocket that may be useful for developing small molecules by selectively targeting the Aurora family kinases.

Understanding the mechanism of ligand binding to proteins is imperative for designing new molecules or screening potential drug molecules from available databases. We have used surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS), which is a highly sensitive technique, to understand the binding of the commonly used hypertension drug, felodipine, to Aurora A kinase. Although NMR (1), X-ray crystallography (2), surface plasmon resonance (3), and fluorescence (4) are experimental techniques used to explore protein–drug interactions and each of these techniques provides unique information about the protein–ligand interaction, a common problem of these techniques is the requirement of a high-protein concentration or the incorporation of secondary tagged molecules and a protein size limit. SERS has been traditionally used for the ultrasensitive detection of analytes. However, it can also be used to examine the protein–small molecule interactions and elucidate the mechanism (5–7). A commonly debated aspect is that SERS does not provide complete vibrational information compared with resonant Raman or normal Raman spectroscopy. Despite the limited information from SERS, which can be performed in proteins at extremely low concentrations in their active state, the competitive binding versus noncompetitive binding and specific changes in protein upon ligand binding can be explained. This approach is extremely effective when combined with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and the structural information of the protein. The usefulness of this combination is that drugs can be screened for therapeutic applications. This paper provides a prelude to this development. This finding also facilitates the developing field of tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy for imaging the small molecule interactions for in vitro and in vivo applications. A completely developed SERS–MD simulation combination with adequate help from the structure of the protein may help converge potential small molecules for therapeutic applications and reduce the time for drug discovery. A major advantage of SERS (and Raman spectroscopy) over X-ray crystallography is that the experiments are carried out with protein in an active state and does not require special preparation of the samples.

We present a previously unidentified class of inhibitor-molecule felodipine and demonstrate its selective inhibition of Aurora A with SERS in a label-free manner and in physiological conditions. The inhibition was achieved using a unique surface-binding mode and was verified by point-mutation inhibition assays based on the inputs from SERS and MD simulations. The feasibility to predicting the binding position of ligands to proteins without the need for crystallizing the complex and conducting X-ray diffraction studies has demonstrated the potential for a complementary technique.

Results

Felodipine Inhibits Aurora A Kinase Activity: Tracked by SERS.

Felodipine, which is a dihydropyridine compound that was discovered as a calcium channel antagonist, is an extensively used antihypertensive drug used to treat high blood pressure accompanied by an increased heart rate (8). A 36% reduction in cancer risk was observed in patients administered felodipine (9). Recent studies have shown that felodipine inhibits cell proliferation in human smooth muscle cell (10). These observations motivated us to evaluate the effect of felodipine on cellular proliferation-related molecular targets.

A previous study from our group had suggested that anacardic acid is an Aurora A specific activator (11). We attempted to address the selective inhibition of Aurora A kinase by differentiating it from the closely related Aurora B kinase. The small-molecule inhibitors that have been shown to target Aurora A specifically are all ATP analogs that bind within the catalytic pocket. In this context we were encouraged to screen a dihydropyridine scaffold (such as felodipine, nitrendipine, nimodipine, nicardipine, and amlodipine) against the Aurora family of mitotic kinases (Fig. S1A). Felodipine and nitrendipine were shown to inhibit the kinase activity of the recombinant, full-length, Aurora A in vitro (Fig. S1 B–E). Felodipine can potently inhibit histone H3 phosphorylation by Aurora A in a dose-dependent manner but has a minimal effect on the homolog Aurora B (Fig. 1).

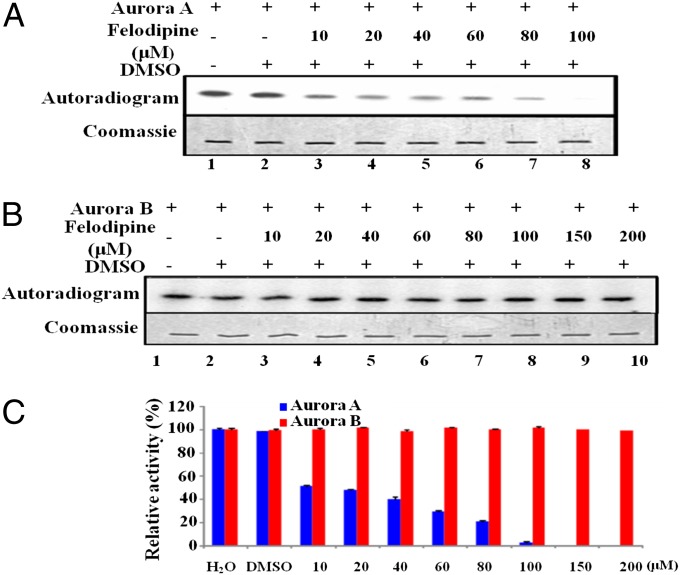

Fig. 1.

Felodipine inhibits Aurora A in a dose-dependent manner. (A) Aurora A (40 ng) was incubated with recombinant histone H3 and 2.5 μM [γ-32P] ATP in the presence of an increasing concentration of felodipine (10, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µM). In a similar experiment (B) histone H3 was incubated with Aurora B (40 ng) and [γ-32P] ATP (lane 1), with DMSO, and with increasing concentration of felodipine (10, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 150, and 200 µM) and subjected to autoradiography. (C) Band intensity was quantified using a Fuji film PhosphorImager analyzer and plotted as a bar chart representing the extent of phosphorylation. Error bars represent SDs calculated for three independent experiments.

As previously mentioned, SERS is an efficient probe for analyzing small-molecule protein interaction. We used SERS to understand the binding and specific inhibition of Aurora A by felodipine. Detailed SERS analysis of Aurora A and B has been performed and discussed (12). We used the mode assignments to discuss our observations. In our previous studies and the SERS studies of Aurora kinases, we demonstrated that silver nanoparticles do not affect kinase activity and do not significantly influence protein structure (12–14). To obtain a suitable SERS spectrum, it is imperative to achieve the effective binding of the protein to the nanoparticle surface. We used negatively charged citrate-capped silver nanoparticles to attach the positively charged regions of the kinase proteins by electrostatic attraction at physiological pH. Fig. 2 shows the SERS of both Aurora A and B in free and complex form with felodipine. A significant change in the spectrum of Aurora A complexed with felodipine compared with the spectrum of Aurora B (Fig. 2) was observed. The SERS spectra of both Aurora A and B are dominated by bands from the aromatic amino acids Phe, Tyr, His, and Trp and the amide bands I, II, and III (12). The amide bands, which are a complex combination of C = O and N–H vibrations, provide information about the secondary structure of a protein. To compare the effects of felodipine with a known inhibitor, we also performed SERS with reversine, which is an ATP analog-competitive inhibitor for both Aurora A and B. To show that protein modes are not influenced by ligand molecules, the nanoparticle solution, the protein buffer, or even the DMSO (Sigma) solvent, we individually conducted the SERS and Raman spectroscopy of these moieties. The results indicated no interference from these factors over the protein spectra (Fig. S2 A–E). Therefore, the new or shifted modes seen in the SERS spectrum of Aurora A–felodipine complex are attributed to the effect of felodipine on the protein.

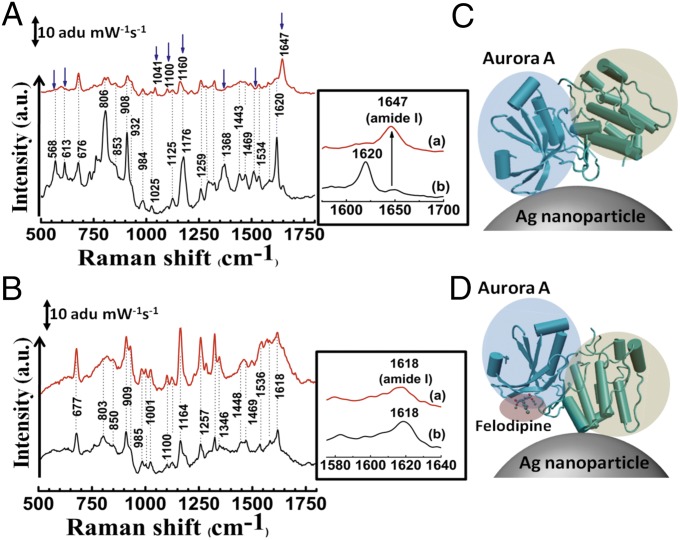

Fig. 2.

SERS study of specific binding of felodipine to Aurora A. (A) SERS spectrum of Aurora A (black) and Aurora A complexed with felodipine (red). (B) SERS spectrum of Aurora B (black) and after treatment with felodipine (red). The change in position of modes and appearance of new modes are indicated by blue arrows in A and amide I bands are highlighted in Insets. (C) Mode of attachment of Aurora A to a silver nanoparticle and (D) change in orientation of Aurora A on the silver nanoparticle surface on complexation with felodipine. The N-terminal β-sheet–rich domain and the C-terminal α-helix–rich domains are highlighted in blue and green, respectively. The bound felodipine in D is highlighted in red.

In quantifying the degree of phosphorylation in the in vitro kinase assay, the results show that felodipine may inhibit the kinase activity of Aurora A with an IC50 value of ∼20 μM (Fig. 1C). The kinase activity of Aurora A may be completely inhibited at a 100-μM concentration of felodipine. In the same assay system, felodipine did not affect the kinase activity of Aurora B at a concentration of 200 μM, which is 10 times higher than the IC50 against Aurora A. These results are consistent with our SERS data.

We have cross-checked our kinase assay by comparing the inhibitory activity of felodipine with the commercially available specific inhibitor of Aurora A MLN8237 with an IC50 of 61 nM (SI Results and Discussion, section 1.1 and Fig. S3) (15). In our kinase assays both felodipine and MLN8237 can inhibit Aurora A without affecting the kinase activity of Aurora B. In addition, felodipine inhibits the autophosphorylation of Aurora A in a dose-dependent manner (SI Results and Discussion, section 1.2 and Fig. S3) with an IC50 of 20 μM (Fig. S3D) and is also determined to have substrate-specific inhibition of Aurora A in cellular systems, as indicated by the assays performed in HeLa S3 (SI Results and Discussion, section 1.3 and Fig. S4). The cellular IC50 for the five cell types in the study (HeLa S3, HEK293T, MCF7, HCT116, and C6 cells) against Aurora A and B kinases were in the range of 6 and 12 μM, respectively (Fig. S4G). The inhibition potential against a panel of 30 mitotic kinases was tested in the presence of 20 micromolar felodipine as listed in Table S1.

Prediction of Unique Surface-Binding Mode Using SERS.

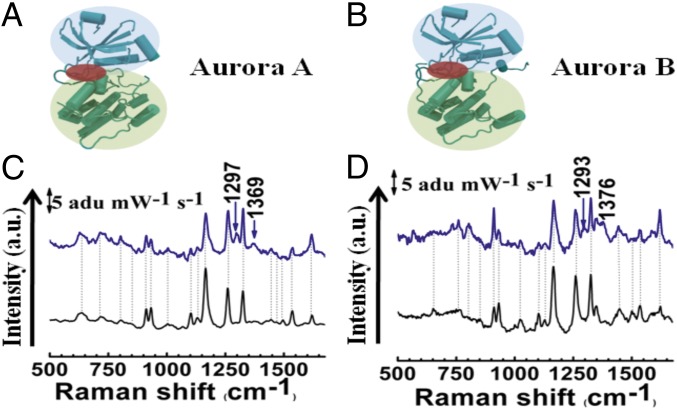

The most significant change in the spectrum of the Aurora A–felodipine complex was the shift of the amide I band from 1,620 to 1,647 cm−1 (Fig. 2A, Inset) which was not observed in the case of the Aurora B–felodipine complex (Fig. 2B, Inset). We believe that felodipine is a surface-binding ligand and the change in the amide I band may have originated from the change in position of the attachment of the protein on the silver surface (schematically represented in Fig. 2 C and D). To confirm this hypothesis, we complexed the protein with another known Aurora A inhibitor–reversine (a dual-competitive inhibitor), which binds in the ATP pocket (Fig. 3 A and B) (16). The choice of reversine was intentional because it inhibits both Aurora A and B and the structural information of binding with Aurora A exists in the literature (16), thus it could act as a control. Because reversine is not a surface-binding ligand, attachment of the protein on a nanoparticle should not be affected and the SERS spectra should not change. As expected, the SERS spectra (Fig. 3 C and D) revealed that the amide band shows no shift in its position on the Aurora A complexed with reversine. In addition, we did not observe any significant change in the protein SERS spectra for either kinase. However, two new peaks appeared at around 1,297 and 1,369 cm−1 for the Aurora A–reversine complex and around 1,293 and 1,376 cm−1 for the Aurora B–reversine complex. To verify whether these originated from the reversine, we performed normal Raman and SERS on the reversine molecule (Fig. S2 C and D). The new peaks, shown in Fig. 3 C and D, corresponded with the strong peaks of the SERS spectra of reversine at high concentrations (2 mM), whereas reversine failed to yield any observable peaks at lower concentrations. These observations suggest that the surface binding of felodipine can be manifested as a noncompetitive inhibition because these binding pockets may be far from the catalytic active site.

Fig. 3.

SERS study of competitive inhibition of Aurora A and B by Reversine. A and B show the structure of Aurora A and B, respectively. The N-terminal β-sheet–rich domain and the C-terminal α-helix–rich domains are highlighted in blue and green, respectively. The ATP binding region where reversine binds is highlighted in red. (C) SERS spectra of Aurora A (black) and Aurora A–reversine complex (blue). (D) SERS spectra of Aurora B (black) and Aurora B–reversine complex (red). New modes are indicated by arrows.

Validation of SERS Results Through Molecular Docking and MD Simulations.

To validate the experimental evidence of felodipine binding to Aurora A, we performed molecular docking to predict the binding site and orientation of felodipine. Molecular docking was assisted by the knowledge of the structure of human Aurora A (17) and B (18). Docking results showed that felodipine binds to a solvent-exposed pocket outside the hinge region (Fig. 4 A and B and Fig. S5A) in the most favorable docked pose (lowest binding energy) and it is in hydrophobic contact with the residues Phe157, Ile-158, and Tyr-212 (Fig. 4B). Moreover, the carbonyl group of felodipine forms a hydrogen bond with the −NH group of the Tyr-212 residue (−O⋅⋅⋅HN, d = 2.05 Å, Ɵ = 170.45°), which is a part of the solvent-exposed front pocket of Aurora A located on the flip side of the catalytic pocket in the hinge region (amino acid residues 210–216). In the case of human Aurora B, the hydrophobic pocket is narrower by ∼2.8 Å (Fig. S5 B, i and ii and C) compared with the hydrophobic pocket of Aurora A because the residues Phe-101 and Ile-102 tilt inwards. Thus, a smaller hydrophobic pocket does not favor felodipine binding at this surface pocket of human Aurora B and selectively inhibits human Aurora A. This change in the hydrophobic pocket is attributed to the differences in the nature of the residues that line it (Lys-156 for Aurora A and His-100 for its counterpart, Aurora B) in the case of human Aurora kinases (Fig. S5D) but not in the case of the Xenopus Aurora kinases (Fig. S5E). Because docking was accomplished with a flexible ligand on a rigid receptor, we also performed MD simulation to consider the flexibility in protein structure from the felodipine binding. The 2-ns MD simulation of the Aurora A–felodipine complex demonstrated the stability of the binding between felodipine and Aurora A. The rmsd distances between the center of masses of felodipine and the residues Phe-157, Ile-158, and Tyr-212 and the protein yielded consistent values over the entire duration of simulation (Fig. S6A).

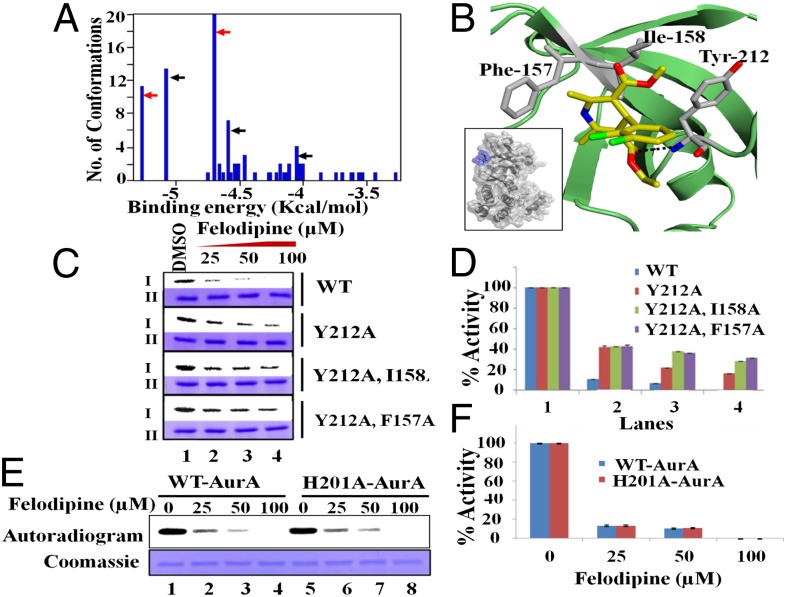

Fig. 4.

Noncompetitive binding of felodipine to Aurora A. (A) Conformational clustering histogram generated from molecular docking of felodipine to Aurora A through Autodock. Red arrows represent the conformations of felodipine bound to the hinge pocket (first site), whereas black arrows represent binding over the N-terminal pocket (second site). (B) The bound configuration of felodipine to Aurora A. The residues colored in gray are in hydrophobic interaction with felodipine. Felodipine is hydrogen bonded to Aurora A through residue Tyr-212 (dotted line). The carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, and chlorine atoms are colored in yellow, red, blue, and green, respectively. Inset shows the felodipine (blue) attached to the surface of Aurora A near the hinge region. (C) Aurora A kinase assay with DMSO control and with an increasing concentration of felodipine using wild type versus mutant kinases (amount normalized with wild-type activity) and subjected to autoradiography. I and II represent autoradiogram and coomassie, respectively. (D) The band intensity was quantified and plotted as a bar chart representing the extent of phosphorylation. Error bars represent SDs calculated for three independent experiments. (E) In vitro kinase assay that compares the wild-type versus second-site mutant (H201A), which is similar to C. (F) The quantification for the same data are represented as a bar chart, which is similar to D.

The comparison of the structures of Aurora A after 2-ns simulation with and without felodipine revealed a number of conformational changes that lined the active site, which may affect the binding of ATP in the ATP-binding pocket (Figs. S5A and S6B). Residues 141–143 in the glycine-rich loop are highly flexible and Lys-143 has been shown to be a switch in the case of ATP binding in Aurora A (19). We also analyzed the second most favorable docked pose in which the felodipine was hydrogen bonded to the residues His-201 and Trp-128. The MD simulations indicated the stability of felodipine in this hydrophobic site (SI Results and Discussion, section 1.4 and Fig. S7 A and C). We also probed the docking of felodipine to another hydrophobic site that is similar to the two previous sites with two aromatic residues coming together (Tyr-334 and Tyr-338). In the course of the MD simulation, felodipine did not exhibit stable binding within this pocket (Fig. S7D). As an analogy to the binding of felodipine with Aurora A selectively, the Aurora B activator protein, INCENP binds in the vicinity of these surface pockets (hinge and N-terminal hydrophobic pocket) over Aurora B but not Aurora A. This finding suggests the uniqueness of one of the hydrophobic binding sites, which can be targeted for selective inhibition of human Aurora kinases.

Point-Mutation and Kinetics Studies.

To physically confirm the binding of felodipine, we performed point-mutation studies. The results confirmed our prediction of the binding site because we obtained a maximum decrease in inhibitory activity of 37% from the complete inhibition of Aurora A activity for 100 μM felodipine (Fig. 4 C and D). Because the complete rescue was not observed, a probable second site is suggested as predicted by docking studies. SERS of Aurora A mutants complexed with felodipine were performed. In case of the combination mutants Ile-158 and Tyr-212, as well as Phe-157 and Tyr-212, significant changes in the SERS spectra were not observed, compared with the changes seen in the wild-type SERS spectra (Fig. S6C). The possibility of a second site binding over the enzyme-inhibition potential of felodipine was validated by performing additional mutations, namely His-201 and Trp-128. Because Trp-128, when mutated to Alanine, did not show any kinase activity, we performed our studies using only the His-201 Ala mutant to compare with the wild-type kinase. Based on the in vitro assay (Fig. 4 E and F), no significant difference in the inhibition level of felodipine was observed against both the Aurora A kinases (wild type versus His-201 Ala) due to the binding of felodipine to the first site. In the case of point-mutant His-201, large-scale changes in the SERS spectrum could be observed when complexed with felodipine. These changes include the shift of the amide I band from 1,625 to 1645 cm−1, which indicates the shift of the attachment point of the nanoparticle to the α-helix domain (Fig. S6 C, iii). These changes are comparable to the SERS spectra of the wild type complexed with felodipine. Thus, the most preferable site of felodipine binding is the hinge pocket surrounded by the hydrophobic residues Phe-157, Ile-158, and Tyr-212.

The data obtained by SERS, molecular docking, and MD suggests that felodipine is an uncompetitive inhibitor of Aurora A. A kinetic characterization of the enzyme inhibition was performed using a fixed concentration of enzyme and histone H3 with an increasing concentration of [γ-32P] ATP in the presence of varying concentrations of felodipine using DMSO as solvent control. The results are presented in SI Results and Discussion, section 1.5 and Fig. S8. It was observed that, unlike the majority of the ATP-competitive inhibitors reported for Aurora kinase, felodipine is a mixed-type inhibitor of Aurora A. These observations indicate that SERS-based prediction of a noncompetitive mode of inhibition is valid.

Cell Cycle and In Vivo Effects of Felodipine: Spindle Pole Defects, Cell Death, and Retardation of Tumor Progression.

The effects of felodipine on the cell cycle were investigated by FACS analysis using four different cell lines: HeLa, HEK293T, MCF7, and HCT116 cells (Fig. S9). The results showed that felodipine can induce a dose-dependent increase in aneuploidy compared with DMSO control (SI Results and Discussion, section 1.6 and Fig. S10 B–E).

Aurora A inhibition induces aneuploidy, which causes cell death (20). We determined that the use of felodipine for the inhibition of Aurora A also induces cell death in HeLa cells, as revealed from the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) assay. Considering untreated cells as a 100% viable population, the viability of cells treated with an increasing concentration of felodipine was compared with the DMSO treatment. Nearly 87% of cell death was observed in the case of 100 µM felodipine-treated cells (Fig. S10A). This finding suggests that felodipine induces cell death in high micromolar concentrations. Mechanistically, the inhibition of Aurora A by felodipine may induce spindle pole defects that cause chromosome congressional problems at metaphase, which results in aneuploidy, as observed in Aurora A knockdown cells (20). Our investigations of the spindle pole morphology in HeLa cells, after felodipine treatment by immunocytochemistry analysis using the anti–α-tubulin antibody, unambiguously established the onset of spindle defects.

Among all cell lines tested for the felodipine-mediated induction of aneuploidy, the most robust effect was observed in the case of the rapidly proliferating C6 glioma cells. Thus, the C6 cell lines were selected to investigate the effect of felodipine in a xenografted nude mice model. We injected 106 cells in the s.c. tissue of the left flank in mice. After 1 wk, these mice were challenged with only DMSO or with felodipine at the rate of 5 mg/kg body weight daily for 4 wk. At the end of every week the tumor size was measured and plotted as the percent tumor progression for mice treated with DMSO and felodipine (n = 3) versus days posttreatment in weeks. We obtained a significant reduction in the tumor progression rate among the mice treated with felodipine compared with mice injected with DMSO (Fig. S10F).

Discussion

In the majority of drug-designing strategies, the small-molecule modulator with the greatest potency is selected. However, the modulator's target specificity is compromised. Similarly, small molecules, which are highly specific, may not be investigated to their full potential due to a high IC50. This scenario becomes more difficult with surface-binding molecules. Based on our results, we located the binding site of one of the surface-binding small-molecule modulators (felodipine), selectively inhibiting Aurora A using SERS, to our knowledge for the first time, and corroborated using molecular docking studies and MD simulations. Due to the simplicity of these studies, the potential to screen drugs and derivatize these small molecules with high IC50 to develop new drugs with better potency exists. Various other advantages and disadvantages of SERS are highlighted in SI Results and Discussion, section 1.7.

SERS to Explain the Noncompetitive Surface-Binding Mode.

SERS was used to show the direct evidence of the unique surface-binding mode for felodipine. The changes observed in the intensity of SERS modes are attributed to the change in the binding nature of the protein to the nanoparticle surface. Structurally Aurora A is bilobed with a N-terminal lobe that primarily consists of β-sheets and a C-terminal lobe, which predominantly consist of α-helices. The 1,620-cm−1 peak is a characteristic peak of the antiparallel β-sheet, which suggests that the N-terminal lobe of the protein is bound to the silver nanoparticle surface. The change in spectra (where the amide I band shifts from 1,620 to 1,647 cm−1) when complexed with felodipine is significant because it suggests that the protein-binding region has been altered due to the presence of felodipine. Note that felodipine possesses a strong hydrophobic region (chloride region) and a hydrophilic region (pyridine region). We did not observe any felodipine signature in the spectra. This result suggests that the hydrophobic region of felodipine faces outwards, repelling the silver because it would prefer to be in a hydrophilic region. This finding also suggests that felodipine is bound to the surface of the protein. Based on the amide I mode obtained from the felodipine-complexed protein, the enzyme is predominantly attached to the nanoparticle’s surface through the α-helix (characteristic amide I bands vary from 1,640 to 1,658 cm−1), which exists in the C-terminal lobe. Based on these observations, two possible events may occur in tandem. The binding of felodipine to the hinge pocket and the second site, which is located in the β-sheet–rich N terminus followed by the blocking of the N-terminal lobe from contacting the nanoparticle surface. Thus, the protein is left with the option of binding the nanoparticle through the α-helical domain. This result is corroborated by large-scale changes in the intensities of modes from aromatic amino acids and other aliphatic side chain modes.

The felodipine binding changes the shape of the ATP-binding hydrophobic pocket; more prominently in the glycine-rich loop (Figs. S5A and S6B). This occurrence is confirmed from the SERS of the Aurora B and Aurora B–felodipine complex. Because we do not find any change in the amide I region, it suggests that felodipine is not binding at the hinge region. Note that Aurora B exhibits a similar structure to Aurora A (21). Because reversine binds to both Aurora A and B competitively from within the ATP-binding pocket (16), it cannot alter the environment around the N-terminal lobe of the protein. The SERS of both Aurora A and B complexed with reversine does not show a change in the amide I mode but shows the appearance of the strong reversine modes around 1,297 and 1,372 cm−1. In addition there was very little change in the intensities of modes of aromatic amino acids in the case of reversine binding to Aurora kinases. The fact that one can see the SERS of reversine (which requires a high concentration to be visible in the absence of protein), suggests that the protein becomes adsorbed onto the silver nanoparticle close to the hinge region toward the N-terminal lobe. Thus, SERS can clearly differentiate different modes of binding for two different molecules and give a hand-waving argument for the different inhibitory mechanisms.

Mechanistic Insights Using Molecular Docking and MD.

Docking and MD studies validated the existence of a unique surface-binding mode in the vicinity of the β-sheet domain, as observed by SERS. The binding of felodipine was ranked according to the binding energies by Autodock (22). The results indicated two potential sites of interaction (Fig. 4A). Felodipine presumably binds near the solvent-exposed hydrophobic pocket outside the hinge region in Aurora A formed by residues Phe-157, Ile-158, and Tyr-212, which has a minimum binding energy and maximum population (first site). These residues create a partly hydrophobic cavity to accommodate the hydrophobic backbone of felodipine, which is lined by a hydrophilic cavity to accommodate the hydrophilic side chains. The change in dimensions of this pocket results in the reduction of the hydrophobic patch in this region by approximately 2.8 Å (Fig. S5C) in the human Aurora kinase, which prevents felodipine from binding to Aurora B and makes it a selective inhibitor for human Aurora A. Binding of a ligand to specific sites on a protein is highly dependent on complementarity in terms of the protein–ligand geometry and electrostatic forces between protein and ligand. Therefore, the detection of binding sites or cavities on proteins has important implications in the area of structural biology. Felodipine exhibits uncompetitive inhibition and reduces the autophosphorylation in Aurora A, which indicates a specific level of conformation changes within the active sites of the protein. These allosteric inhibitors, which bind outside the active site of the protein, cause global conformational change and regulate the kinase activity of the protein target. MD considers the flexibility of the protein and shows a distinct conformational change in the residues lining the active site of the protein. Residues 141–143 are flexible and have high rmsd values, as shown in Fig. S6B. The residue Lys-143 has been shown to be crucial for the binding and release of ATP in the binding site. The state of Lys-143 is controlled by the hydrogen-bonded network between TPX2, which activates Aurora A and the β-sheet region connected to the glycine-rich loop that undergoes translational movement. Because felodipine engages in a hydrophobic interaction with the residues Phe-157 and Ile-158, both of which are part of the β-sheet region, the movement of the glycine-rich loop is expected to occur in the same manner. The global alteration in the conformation is also communicated to the α-helix loop (Fig. S5A), which is responsible for maintaining the phosphorylated Thr-288 in its active conformation. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments suggest the existence of two binding sites. The second site was also predicted by Autodock. This site is located on the N-terminal domain of Aurora A, which is lined by the residues Trp-128 and His-201. Although the MD simulation exhibits the stable binding of felodipine, biochemical assays that use the point mutants did not show any perturbation at the level of the kinase activity for the tested mutant. The lack of activity in the Trp-128 mutant did not allow us to biochemically corroborate the binding convincingly over this pocket. MD simulations also show a slight perturbation of the ATP-binding pocket (residues 210–215; Fig. S6D) after complexing with felodipine at the second site. This situation may be the reason that rescue is not completely achieved with the first site mutants.

Role of Felodipine.

Because felodipine shows inhibition of Aurora A autophosphorylation and substrates, such as TACC3 and H3S10, it may confer cytotoxicity. Thus, additional derivitization based on the information obtained from this study can lead to the development of specific Aurora A inhibitors, which may serve as future antitumor therapeutics.

The majority of the known small molecules that inhibit Aurora kinase are competitive inhibitors that bind to the ATP-binding pocket of the enzymes (23). However, few inhibitors that selectively inhibit Aurora A, such as MLN8054 (24) and MLN8237 (25), exist. MLN8054 possess a benzazepine core scaffold with a fused amino pyrimidine ring and an aryl carboxylic acid that shows ATP-competitive and reversible inhibition of recombinant Aurora A with an IC50 of 42 nM; it had failed in phase I clinical trials on advanced solid tumors (24). Similarly MLN8237 is also a selective and potent competitive inhibitor of Aurora A, which has a pyrimidine-fused benzazepine scaffold with an IC50 of 61 nM. Felodipine, on the other hand, is an uncompetitive inhibitor of Aurora A with low micromolar IC50. MLN8054 treatment induces G2/M arrest due to spindle defect, and prolonged treatment induces aneuploidy, which ultimately leads to apoptosis. A similar effect may also be observed after felodipine treatment, which indicates that felodipine inhibits Aurora A in the cellular system. MLN8054 induces 82% spindle abnormality (26), whereas felodipine can induce a maximum spindle abnormality of 40%. Felodipine was found to be cytotoxic, which may be attributed to its dihydropyridine scaffold. This assumption is supported by the fact that the dihyropyridine group of compounds can reverse drug resistance in multidrug-resistant cancer cells (27, 28). Further, this class of drugs may block the dihydropyridine receptor (DHPR) thereby reducing the cytosolic Ca2+levels essential for activating the calcium dependant signaling events. Recently, Ca2+ was shown to activate Aurora A autophosphorylation in a calmodulin (CaM)-dependant manner (24, 29). Our current observations and previous studies (30) suggest that felodipine, can also inhibit calcium-mediated activation because dihydropyridine can block the cytosolic Ca2+ release by blocking the DHPR, which is an indirect means by which Aurora A activity is inhibited within the cell. Furthermore, many other CaM-dependent pathways may be blocked within the cell.

Collectively, these data suggest that felodipine induces aneuploidy by inhibiting Aurora A and causing G2/M arrest. The majority of these effects comprise only a part of the function served by felodipine, with many unidentified targets, which requires careful investigation to design more potent and selective inhibitors of Aurora A. In addition, our observations indicated a reduction in the tumor progression rate among the mice treated with felodipine. Although felodipine cannot be administered to achieve micromolar concentrations in vivo, the multiple modes of action, such as calcium channel blockade and CaM pathway blocking, and additionally, the direct inhibition of Aurora A kinase, prove effective in the total retardation of tumor growth.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that SERS can be performed at relatively low concentration and provide vital insight into the binding of small molecules to the protein. With the structural information of the protein, molecular docking, and MD studies, we can corroborate these results and highlight the binding site of the small molecule on the protein. This finding has been demonstrated in the case of Aurora kinases and felodipine. SERS can distinguish between surface binding and competitive binding of small molecules of Aurora A kinase. Point mutations performed on the Aurora kinase confirm the binding mechanism predicted by these techniques. Thus, SERS, molecular docking, and MD can be combined to provide an alternative to the current methods used for drug discovery. A properly developed SERS methodology for individual proteins can be used for rapid screening of possible ligands for therapeutic applications. At this juncture, we are enthusiastic to think that, as with valproic acid (31), felodipine-related compounds may soon also be considered as antineoplastic therapeutics.

Materials and Methods

Purification of Enzymes and Substrates and Kinase Assay.

Aurora A and B enzymes expressed as C-terminal His6-tagged proteins were purified using Ni⋅nitrilotriacetic acid affinity purification from the respective, recombinant baculovirus infected Sf21 cells. Details of the procedure, kinetic assay, and ITC experiments are described in SI Materials and Methods, sections 2.1–2.3.

Cell Culture, Treatment, Immunoblotting Analysis, and FACS Analysis.

The preparation of mammalian cells and the methods for immunoblotting, cell cycle analysis, and FACS are described in SI Materials and Methods, section 2.4.

MTS Assay and Immunofluorescence.

Details on the MTS and immunofluorescence assays performed on cultures of HeLa cells treated with DMSO/felodipine are explained in SI Materials and Methods, section 2.5.

Ethics Statement and Animal Experiment.

All animal experiments were performed as per committee for the purpose of control and supervision of experiments on animals (CPSEA) guidelines with the approval of animal facility, Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research. Nude mice procured from the National Institute of Virology (Pune, India) were used for tumor growth rate studies. For details, see SI Materials and Methods, section 2.6.

Raman and SERS.

All Raman and SERS measurements were performed using a custom-built Raman spectrometer. The instrumentation and sample preparation methods are discussed in SI Materials and Methods, section 2.7.

MD Simulations.

The initial structures of human Aurora A and B were obtained from the Protein Data Bank [ID codes 1MQ4 (32) and 4AF3 (18)]. The structures of ligands were optimized by the Gaussian 09 program (33). The MD simulation of human Aurora A was performed by the MD package nanoscale molecular dynamics (NAMD, Version 2.8; www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/namd) using the chemistry at Harvard molecular mechanics 22 (CHARMM22) (34) force field. Details of the methods are discussed in SI Materials and Methods, section 2.8.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Dipak Dasgupta and Amrita Banerjee (Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics) for ITC experiments and B. S. Suma for imaging. T.K.K. acknowledges the financial support of Department of Biotechnology, Grant BT/01/CEIB/10/III/01, and a J. C. Bose National Fellowship. D.K. acknowledges a Council of Scientific and Industrial Research Senior Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1402695111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Goldflam M, Tarragó T, Gairí M, Giralt E. NMR studies of protein–ligand interactions. In: Shekhtman A, Burz DS, editors. Protein NMR Techniques, Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol 831. Clifton, NJ: Humana Press; 2012. pp. 233–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schlichting I. 2005. X-ray crystallography of protein-ligand interactions. Protein–Ligand Interations: Methods and Applications, Methods in Molecular Biology, ed Nienhaus GU Humana Press, Totowa, NJ), Vol 305, pp 155–165.

- 3.Kuroki K, Maenaka K. Analysis of receptor–ligand interactions by surface plasmon resonance. In: Rast JP, Booth JWD, editors. Immune Receptors, Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol 748. Clifton, NJ: Humana Press; 2011. pp. 83–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Möller M, Denicola A. Study of protein-ligand binding by fluorescence. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2002;30(5):309–312. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arif M, Kumar GVP, Narayana C, Kundu TK. Autoacetylation induced specific structural changes in histone acetyltransferase domain of p300: Probed by surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111(41):11877–11879. doi: 10.1021/jp0762931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mantelingu K, et al. Activation of p300 histone acetyltransferase by small molecules altering enzyme structure: Probed by surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111(17):4527–4534. doi: 10.1021/jp067655s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mantelingu K, et al. Specific inhibition of p300-HAT alters global gene expression and represses HIV replication. Chem Biol. 2007;14(6):645–657. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elmfeldt D, Hedner T. Felodipine—a new vasodilator, in addition to beta-receptor blockade in hypertension. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1983;25(5):571–575. doi: 10.1007/BF00542340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu L, et al. FEVER Study Group The Felodipine Event Reduction (FEVER) Study: A randomized long-term placebo-controlled trial in Chinese hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 2005;23(12):2157–2172. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000194120.42722.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Z, et al. Felodipine inhibits nuclear translocation of p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinase and human smooth muscle cell growth. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53(1):227–231. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00419-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kishore AH, et al. Specific small-molecule activator of Aurora kinase A induces autophosphorylation in a cell-free system. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;51(4):792–797. doi: 10.1021/jm700954w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siddhanta S, Karthigeyan D, Partha PK, Kundu TK, Narayana C. Surface enhaced Raman spectroscopy of Aurora kinases: Direct, ultrasensitive detection of autophosphorylation. RSC Advances. 2012;3:4221–4230. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar GVP, Selvi R, Kishore AH, Kundu TK, Narayana C. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopic studies of coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112(21):6703–6707. doi: 10.1021/jp711594z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pavan Kumar GV, Ashok Reddy BA, Arif M, Kundu TK, Narayana C. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering studies of human transcriptional coactivator p300. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110(33):16787–16792. doi: 10.1021/jp063071e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manfredi MG, et al. Characterization of Alisertib (MLN8237), an investigational small-molecule inhibitor of aurora A kinase using novel in vivo pharmacodynamic assays. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(24):7614–7624. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D’Alise AM, et al. Reversine, a novel Aurora kinases inhibitor, inhibits colony formation of human acute myeloid leukemia cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7(5):1140–1149. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheetham GMT, et al. Crystal structure of aurora-2, an oncogenic serine/threonine kinase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(45):42419–42422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200426200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elkins JM, Santaguida S, Musacchio A, Knapp S. Crystal structure of human aurora B in complex with INCENP and VX-680. J Med Chem. 2012;55(17):7841–7848. doi: 10.1021/jm3008954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu X, Wang X, Xiao Z, Li Y, Wang Y. Two TPX2-dependent switches control the activity of Aurora A. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(2):e16757. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garuti L, Roberti M, Bottegoni G. Small molecule aurora kinases inhibitors. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16(16):1949–1963. doi: 10.2174/092986709788682227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown JR, Koretke KK, Birkeland ML, Sanseau P, Patrick DR. Evolutionary relationships of Aurora kinases: Implications for model organism studies and the development of anti-cancer drugs. BMC Evol Biol. 2004;4(1):39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-4-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris GM, et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2009;30(16):2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manfredi MG, et al. Antitumor activity of MLN8054, an orally active small-molecule inhibitor of Aurora A kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(10):4106–4111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608798104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plotnikova OV, Pugacheva EN, Dunbrack RL, Golemis EA. Rapid calcium-dependent activation of Aurora-A kinase. Nat Commun. 2010;1:64. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sloane DA, et al. Drug-resistant aurora A mutants for cellular target validation of the small molecule kinase inhibitors MLN8054 and MLN8237. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5(6):563–576. doi: 10.1021/cb100053q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehdipour AR, Javidnia K, Hemmateenejad B, Amirghofran Z, Miri R. Dihydropyridine derivatives to overcome atypical multidrug resistance: Design, synthesis, QSAR studies, and evaluation of their cytotoxic and pharmacological activities. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2007;70(4):337–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoar K, et al. MLN8054, a small-molecule inhibitor of Aurora A, causes spindle pole and chromosome congression defects leading to aneuploidy. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(12):4513–4525. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02364-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou XF, Yang X, Wang Q, Coburn RA, Morris ME. Effects of dihydropyridines and pyridines on multidrug resistance mediated by breast cancer resistance protein: In vitro and in vivo studies. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33(8):1220–1228. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.003558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plotnikova OV, et al. Calmodulin activation of Aurora-A kinase (AURKA) is required during ciliary disassembly and in mitosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23(14):2658–2670. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-12-1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walsh MP, Sutherland C, Scott-Woo GC. Effects of felodipine (a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker) and analogues on calmodulin-dependent enzymes. Biochem Pharm. 1988;37(8):1569–1580. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blaheta RA, Cinatl J., Jr Anti-tumor mechanisms of valproate: A novel role for an old drug. Med Res Rev. 2002;22(5):492–511. doi: 10.1002/med.10017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nowakowski J, et al. Structures of the cancer-related Aurora-A, FAK, and EphA2 protein kinases from nanovolume crystallography. Structure. 2002;10(12):1659–1667. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00907-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frisch MJ, et al. Gaussian 09, Revision B.01. Wallingford, CT: Gaussian, Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacKerell AD, et al. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102(18):3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.