Significance

Stressful cellular events cause intracellular Ca2+ dysregulation, rapid loss of inner mitochondrial membrane potential [the permeability transition (PT)], metabolic dysfunction, and death. Rapid Ca2+-induced uncoupling is one of the most important regulators of cell demise. We show that the c-subunit ring of the F1FO ATP synthase forms a voltage-sensitive channel, the persistent opening of which leads to PT and cell death. In contrast, c-subunit channel closure promotes cell survival and increased efficiency of cellular metabolism. The c-subunit channel is therefore strategically located at the center of the energy-producing complex of the cell to regulate metabolic efficiency and orchestrate the rapid onset of death and thus is a candidate for the mitochondrial PT pore.

Keywords: metabolism, necrosis, apoptosis, ion channel, excitotoxicity

Abstract

Mitochondria maintain tight regulation of inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) permeability to sustain ATP production. Stressful events cause cellular calcium (Ca2+) dysregulation followed by rapid loss of IMM potential known as permeability transition (PT), which produces osmotic shifts, metabolic dysfunction, and cell death. The molecular identity of the mitochondrial PT pore (mPTP) was previously unknown. We show that the purified reconstituted c-subunit ring of the FO of the F1FO ATP synthase forms a voltage-sensitive channel, the persistent opening of which leads to rapid and uncontrolled depolarization of the IMM in cells. Prolonged high matrix Ca2+ enlarges the c-subunit ring and unhooks it from cyclophilin D/cyclosporine A binding sites in the ATP synthase F1, providing a mechanism for mPTP opening. In contrast, recombinant F1 beta-subunit applied exogenously to the purified c-subunit enhances the probability of pore closure. Depletion of the c-subunit attenuates Ca2+-induced IMM depolarization and inhibits Ca2+ and reactive oxygen species-induced cell death whereas increasing the expression or single-channel conductance of the c-subunit sensitizes to death. We conclude that a highly regulated c-subunit leak channel is a candidate for the mPTP. Beyond cell death, these findings also imply that increasing the probability of c-subunit channel closure in a healthy cell will enhance IMM coupling and increase cellular metabolic efficiency.

Mitochondria produce ATP by oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Leak currents in the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) reduce the efficiency of this process by uncoupling the electron transport system from ATP synthase activity. Many studies have described the biophysical and pharmacological features of an IMM pore [the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP)] that is responsible for a rapid IMM uncoupling, causing osmotic shifts within the mitochondrial matrix in the setting of cellular Ca2+ dysregulation and adenine nucleotide depletion (1–4). Some studies suggest that such uncoupling also functions during physiological events and that the mPTP may transiently operate as a Ca2+-release channel (5–7). Although models for the molecular identity of the mPTP have been proposed (8), deletions of putative components, such as adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT) and the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC), have failed to prevent rapid depolarizations (9). In the meantime, nonpore forming regulatory components of the mPTP, such as cyclophilin D (CypD), have been extensively investigated (10, 11).

We recently reported a leak conductance sensitive to ATP/ADP and the Bcl-2 family member B-cell lymphoma-extra large (Bcl-xL) within the membrane of isolated submitochondrial vesicles (SMVs) enriched in ATP synthase (12, 13). We demonstrated binding of Bcl-xL within F1 to the beta-subunit of the ATP synthase, suggesting that the channel responsible for the leak conductance lies within the membrane portion (ATP synthase FO) and that Bcl-xL binding to F1 might close the leak. Recent studies also support the idea that the mPTP is located within the multiprotein–lipid complex of the ATP synthase (10, 14, 15); however, a review of these articles confirms that the specific protein responsible for pore formation remains undetermined (16). We now describe that the purified c-subunit of the mammalian ATP synthase, when reconstituted into liposomes, forms a voltage-dependent channel sensitive to adenine nucleotides, recombinant F1 beta-subunit protein, and anti–c-subunit antibodies. In cells, fluorescent labeling of the c-subunit detects ring opening and closing in response to Ca2+ and the mPTP inhibitor cyclosporine A (CsA). C-subunit single-channel conductance is increased by permanent loosening of the c-subunit ring structure by specific mutagenesis, promoting cell death. In contrast, depletion of the c-subunit in cells inhibits Ca2+-induced IMM depolarization and cell death. Finally, we show that high matrix Ca2+ dissociates the c-subunit ring from the ATP synthase enzyme in F1, providing a mechanism for PT.

Results

The Purified C-Subunit Lacks Regulatory Components and Forms a Voltage-Sensitive Conductance When Reconstituted into Liposomes.

ATP synthase comprises an extrinsic catalytic domain (F1) and a membrane-bound portion (FO) connected by a central stalk and a peripheral stator. Movement of protons down their electrochemical gradient through a translocator at the junction between subunit-c and -a of FO provides the energy used by the alpha- and beta-subunits of F1 to synthesize ATP (17). The octameric c-subunit forms a central pore-like structure that could conceivably allow for uncoupling when exposed. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the role of the c-subunit in IMM uncoupling. Mammalian c-subunit is encoded on three separate nuclear genes (ATP5G1 to -3). Antibodies raised against the common sequence discerned 8-kDa and 15-kDa bands (Fig. S1A). ATP5G1-encoded myc/FLAG-tagged c-subunits were purified from HEK 293T cells (Fig. S1B). In the absence of denaturation, purified c-subunit was detected at ∼250 kDa, suggesting the presence of oligomers (Fig. S1C) (for endogenous oligomers, see Fig. 5G); similar c-subunit–containing complexes have been observed previously (18). Either an antibody raised against ATP5G or an ATP synthase (F1 binding) immunocapture antibody immunoprecipitated multiple subunits of ATP synthase (Fig. S2A), suggesting that the antibodies find epitopes within F1 and FO in the assembled ATP synthase complex.

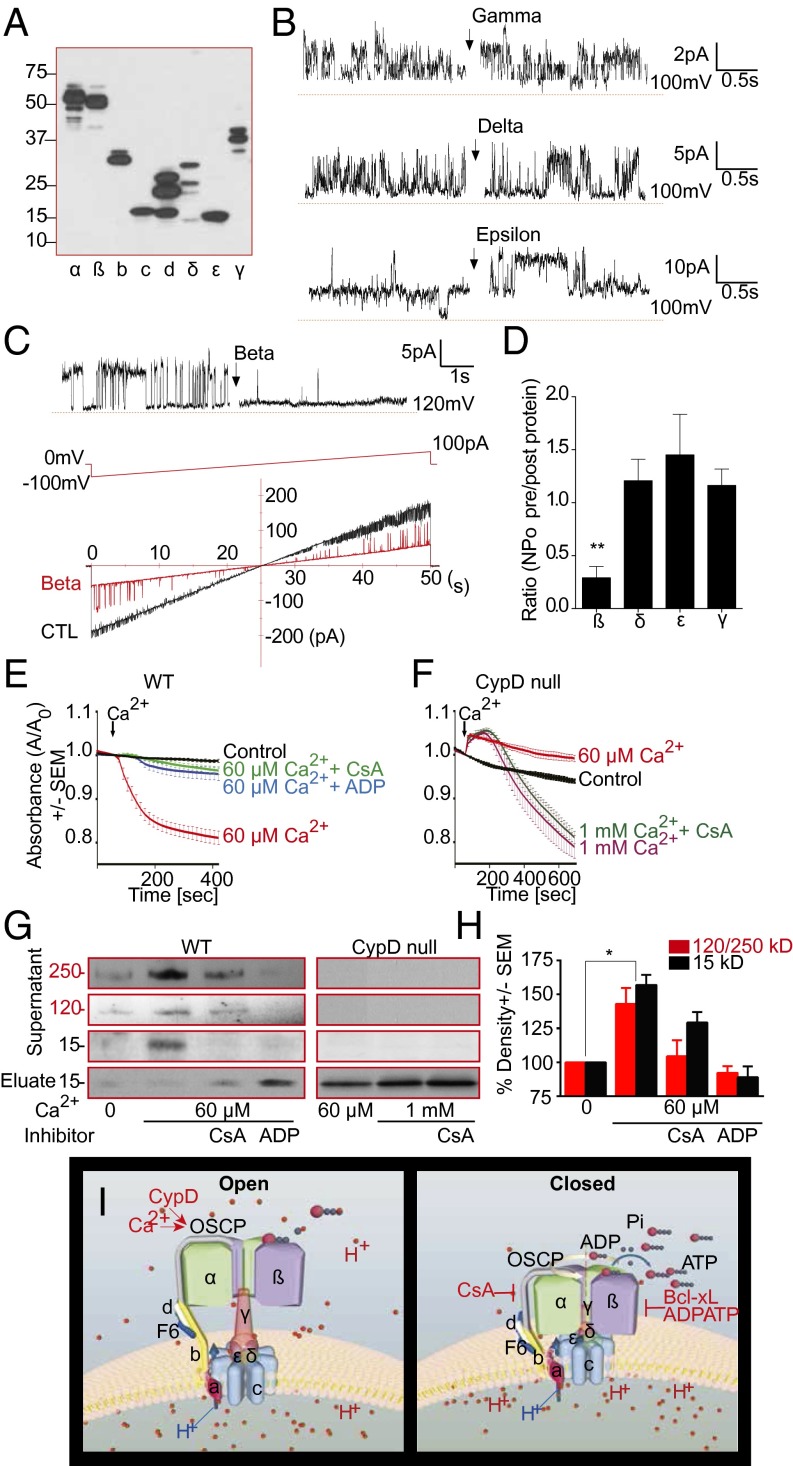

Fig. 5.

Structural rearrangements of ATP synthase unmask the c-subunit pore. (A) Immunoblot using antibody against mammalian myc/FLAG-tagged human ATP synthase subunit proteins (blot representative of 3 blots). (B and C) Representative proteoliposome patch clamp recordings of purified c-subunit. Purified gamma, delta, epsilon or beta-subunit (50 ng/µL recording solution) were added (arrow). (C, Lower) Ramp voltage recording. (D) NPO ratio after/before addition of indicated ATP synthase subunits (n = 5, **P = 0.0036). (E and F) Ca2+-induced IMM swelling assay of WT heart or CypD KO mitochondria in 200 nM CsA or 0.5 mM ADP. Plotted is ratio of absorbance at 540 nm (A) after/before Ca2+ (n ≥ 3 each). (G) Immunoblots (ATP5G-com or ATP5G1) of the supernatants and eluates after ATP synthase IP from WT and CypD KO mitochondrial lysates, as in E and F (representative of ≥4 blots). (H) Quantification of 15-kDa band and 120 plus 250 kDa oligomer band density in gels represented in G (n ≥ 3 for all bands, *P = 0.0331 for 120 plus 250 kDa and 0.0417 for 15 kDa compared with control). (I) Schematic of regulation of PT (c-subunit) pore by ATP synthase F1. (Left) CypD and Ca2+ expand the c-subunit ring and open the pore by releasing F1. (Right) CsA, Bcl-xL, and ADP/ATP close the c-subunit pore by positioning beta-subunit over its mouth.

The purified c-subunit was reconstituted into liposomes in its native form. Immunoblotting confirmed the absence of regulatory moieties in the purified c-subunit elution including ANT, VDAC1, CypD, ATP synthase b-subunit, and oligomycin sensitivity conferring protein (OSCP) (Fig. S1 C and E). The c-subunit was localized to the liposomes by immunolabeling (Fig. S1D). Recordings of excised patches from the proteoliposomes demonstrated a multiconductance channel with prominent subconductance states (Fig. 1A). Recordings of empty liposomes showed no activity (n = 3). Patches contained an ∼100-pS conductance as a subconductance state of multiconductance activity, with peak conductances of up to ∼1.5–2 nS (Fig. 1A), similar to activity described previously for the mitochondrial multiple conductance channel (MCC) (11, 19–21). Also consistent with MCC, channel activity showed negative rectification (Fig. 1B and Fig. S3C). At very positive patch pipette potentials of over 100 mV, channel conductances of ∼1.5 nS and ∼2 nS were also consistently observed (Fig. 1 A–D).

Fig. 1.

ATP synthase c-subunit ring forms a large conductance ion channel. (A, Upper) Excised proteoliposome patch-clamp recording of purified c-subunit protein. (Left) Amplitude histogram shows conductances of ∼227 pS, 1,450 pS, and 1,680 pS; C, closed; O1–O3, open. (Right) Amplitude histograms of six random recordings taken after depolarization of the patch. The histogram from the Left is indicated in red. C is closed; O1–O3 mark the open levels at conductances of ∼100–300 pS, ∼1,500 pS, and ∼1,800–2,000 pS. Conductance levels of ∼500–750 pS are also seen but not designated in the figure. (B) Representative (∼600 pS) excised proteoliposome patch-clamp recording of purified c-subunit protein during continuous ramp voltage clamp from −100 mV to +100 mV before and after 1 mM ATP. (C) Representative patch-clamp recordings of purified c-subunit protein before and after exposure to anti–pan-ATP5G1/2/3 (C-Sub ab.), control antibody (IgG), or 2 µM CsA. (D) Quantification of peak conductance before and after exposure to anti-ATP5G1/2/3 (n = 10, **P = 0.0022), control IgG (n = 3), 100 µM Ca2+ (n = 3), or 2 µM CsA (n = 4). (E) Representative patch-clamp recordings of purified ATP synthase reconstituted into liposomes before and after addition of (in sequence) recombinant CypD protein (5 µg/mL final), 100 µM CaCl2, and 5 µM CsA. (F) Group data for recordings represented in E (n = 12; *P = 0.0228, **P = 0.00391). Closed state of channel activity indicated by the dotted red line.

Such channel currents are not likely to represent movement of protons through the ATP synthase proton translocator because of their very high conductance, lack of ion selectivity, and the absence of the a-subunit in the liposome recordings. For example, the channel was only 1.5 times more selective for Na+/K+ (Fig. S3). In addition, although we could not specifically measure proton conductance electrophysiologically, it is unlikely that protons are excluded from such a large, nonselective channel. In summary, the nonselective, high-conductance c-subunit channel could conduct leak current that uncouples the IMM.

In a previous study, we measured a large leak conductance in the IMM directly by patch clamping SMVs isolated from native rat brain (12). Here, we show that ATP blocks this activity with an EC50 of ∼50 µM (Fig. S4 A and B). However, parallel experiments with purified reconstituted c-subunit demonstrate decreased sensitivity to ATP, with an EC50 of 660 µM (Fig. 1B and Fig. S4 C–F). These data suggest that some ATP sensitivity is localized directly within the c-subunit itself and that other ATP binding sites are removed during partial (urea-treated SMVs) or complete c-subunit purification. The purified c-subunit channel activity was equally attenuated by ATP, ADP, or AMP (Fig. S4F) so ATP hydrolysis by ATP synthase is not likely to be required for its inhibition. Because there appear to be multiple sites of inhibition by ATP within F1FO ATP synthase, we used a more specific inhibitor of the purified c-subunit channel, the anti–pan-c-subunit antibody, which rapidly and effectively attenuated purified c-subunit conductance (Fig. 1 C and D). We found similar antibody-mediated attenuation in SMVs after exposure to Ca2+, a known activator of mPTP (Fig. 2A). These data strongly support the notion that the c-subunit forms the pore of the Ca2+-sensitive mPTP.

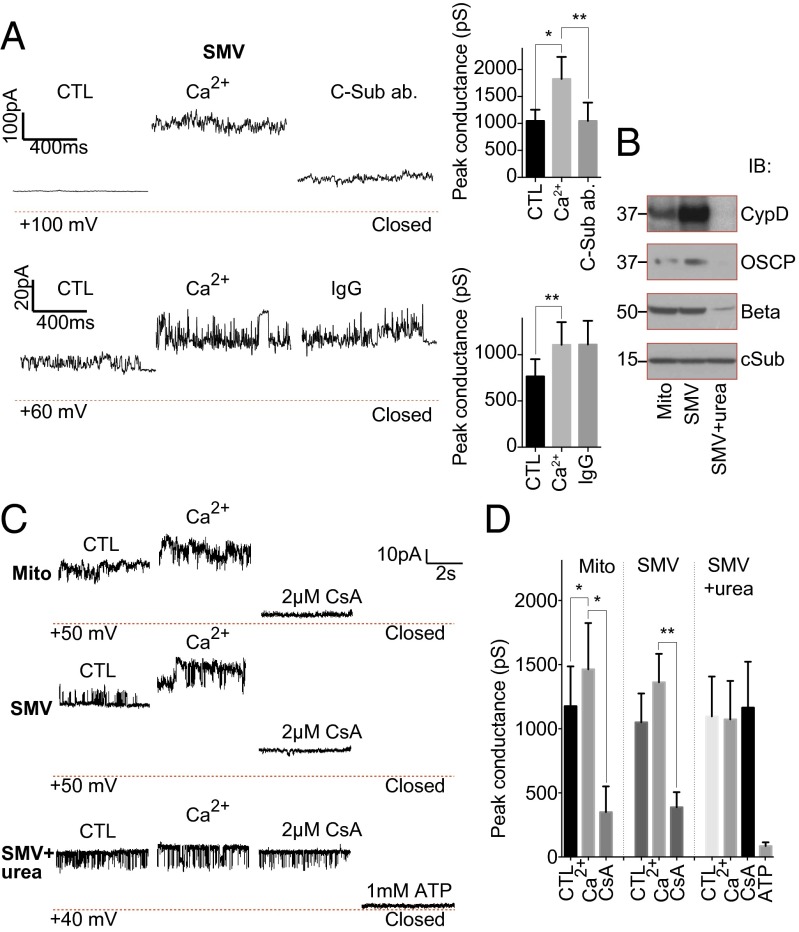

Fig. 2.

The c-subunit large conductance ion channel is present in mitochondria. (A) Representative (∼1,900 pS, Upper; ∼1,000 pS, Lower) SMV patch-clamp recordings before and after exposure to 100 µM Ca2+ followed by anti-ATP5G1/2/3 (C-sub ab.) or control antibody (IgG). Bar graphs show quantification of peak conductances (Upper, N = 8, *P = 0.0194, **P = 0.0033; Lower, N = 5, **P = 0.0256). (B) SDS immunoblot of mitochondria, SMVs, and urea-treated SMVs. C-sub ab is to ATP5G1. (C) Representative patch-clamp recordings of whole-liver mitochondria, SMVs, and urea-exposed SMVs before and after treatment with Ca2+ then CsA and ATP (Bottom trace). (D) Peak conductance in response to Ca2+, CsA, and ATP (n = 4 Mito, 5 SMV, 10 urea-treated SMV, 5 ATP; *P = 0.0045, **P < 0.0001). Closed (0 pA) indicated by the dotted red line.

A number of lines of evidence, including our ATP concentration-dependence data, suggested that the purified c-subunit channel lacked regulatory components that might control its activity in vivo. The mPTP is sensitive not only to high levels of intramatrix Ca2+, but also to the protein CypD (22, 23), possibly by its binding to OSCP on the F1 stator, and to CsA, which may interfere with the CypD–OSCP interaction (10, 15, 21). We performed electrophysiology on three preparations to study the following: (i) purified recombinant c-subunit preparations lacking CypD and OSCP (Fig. S1 C and E) that were reconstituted into proteoliposomes, (ii) purified ATP synthase monomers lacking CypD (Fig. S2 B and C) reconstituted into proteoliposomes, and (iii) mitochondria and SMVs containing endogenous CypD and OSCP (Fig. 2B). In keeping with the lack of Ca2+ and CsA sensitive sites present in the purified c-subunit ring, neither Ca2+ nor CsA had an effect on channel activity of the purified c-subunit (Fig. 1 C and D). Purified monomeric ATP synthase had F1-related enzymatic activity and contained OSCP but lacked CypD (Fig. S2 B and C) (15). When reconstituted into liposomes, monomeric ATP synthase showed infrequent channel activity significantly enhanced by the addition of recombinant CypD protein whether or not Ca2+ was present; channel activity was readily inhibited by CsA (Fig. 1 E and F). Finally, we recorded channel activity of whole mitochondria, SMVs, and SMVs that were exposed to urea to denature and remove extramembrane proteins, including F1 components such as OSCP, beta-subunit, and CypD (Fig. 2B). Channel activity of mitochondria and SMVs revealed robust Ca2+ and CsA responsiveness that was completely absent from the urea-exposed SMVs although 1 mM ATP still rapidly inhibited the channel activity (Fig. 2 C and D). These recordings confirm that Ca2+, CypD, and CsA regulate an IMM conductance by binding to an extramembrane protein site, possibly within the OSCP-subunit of ATP synthase, and explain why Ca2+ and CsA have little effect on the conductance of the purified c-subunit channel.

The C-Subunit Leak Channel Undergoes Measurable Conformational Changes upon Entering the Open and Closed States.

To determine whether the c-subunit ring structure within the ATP synthase responds to CsA and Ca2+ in cells, we adapted a fluorescent method, bipartite tetracysteine display (FlAsh), which detects protein–protein interactions in living cells and localizes proteins to subcellular compartments (24–26). When two pairs of cysteines placed on proteins come in close proximity, they bind tightly to the FlAsh dye, increasing its fluorescence intensity (Fig. 3A). We expressed in separate experiments two constructs, each containing a cysteine pair inserted into ATP5G1 (C sub 1 or C sub 2) (Fig. 3 A–D). At 48 h after transfection, FlAsh fluorescence was apparent at high levels at puncta colocalized with mitochondria within the cells (Fig. 3 B–D), suggesting that the individual c-subunit proteins were in relatively close proximity, as expected. However, only background FlAsh fluorescence was observed in the absence of cysteine binding partners or after transfection of a construct expressing a single pair of cysteines on OSCP (Fig. 3 C and D). Specimens were then exposed to vehicle or CsA, followed by ionomycin to increase intracellular and matrix Ca2+ (Fig. 3 C and D). In the C sub 1- and C sub 2-expressing cells, FlAsh fluorescence was significantly higher in cells preexposed to CsA, suggesting that channel inhibition brings individual FlAsh-labeled c-subunits closer together, thus increasing the packing of the c-subunit ring. Ionomycin decreased FlAsh fluorescence, which was prevented by CsA, suggesting that pore opening loosens the packing of the c-subunit ring. In cells in which two cysteine pairs were inserted on OSCP, FlAsh fluorescence was high, as expected, but failed to respond to ionomycin or CsA (Fig. 3 C and D), indicating no relative movement of the two cysteine pairs in response to the addition of Ca2+ when both were located on the monomeric OSCP. Overall, these studies suggest that activation or inhibition of the c-subunit channel results in changes in the structure of the c-subunit ring that are correlated with changes in c-subunit channel conductance.

Fig. 3.

The c-subunit ring regulates Ca2+-induced IMM uncoupling. (A) Schematic of cysteine pair labeling of two adjacent c-subunit monomers in the open and closed position. Binding by FlAsh and subsequent fluorescence occur when cysteine pairs move together. (B) Representative TMRE, FlAsh fluorescence, and merged image in HEK 293T cells. (C) Time course of FlAsh fluorescence intensity in HEK 293T cells 72 h after transfection (CC-CC indicates two cysteine pairs, and CC indicates one cysteine pair). Cells were pretreated with vehicle or 2 µM CsA for 1 h and exposed to 2 µM ionomycin (Ion., arrow). (D) Group data for FlAsh fluorescence intensity (n = 12 data points and ≥3 independent experiments per condition; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.0001, N.S., not significant). (E) Time course of calcein fluorescence intensity before and after addition of 1 µM (for CsA experiment) or 4 µM ionomycin to HEK 293T cells treated with 5 µM CsA or transfected with the indicated shRNA constructs (Scr, scrambled). (F) Group data for experiment in E at 20 min after addition of ionomycin (n = 3 cells, 16 cells, 13 cells, 18 cells for CsA (1 culture), scrambled, ATP5G3, and ATP5G1 shRNA (three independent cultures) (***P < 0.0001). (Scale bar: 10 μm.)

C-Subunit Depletion Prevents PT.

Ca2+-induced PT can be quantified in live cells by examining IMM permeability and electrical potential (Δψm) (10, 11, 27). To determine whether the c-subunit ring is necessary for such rapid uncoupling in intact cells, we depleted HEK 293T cells of c-subunit proteins by shRNA (Fig. 4A) and then tested cells for IMM permeabilization using calcein/cobalt quenching (7). After the addition of ionomycin to the control cells, a rapid drop in mitochondrial calcein fluorescence was measured, with a time course correlated with changes seen in FlAsh fluorescence (compare Fig. 3 C and E); the drop in calcein fluorescence was prevented by CsA or depletion of c-subunit isomers ATP5G1 or ATP5G3 (Fig. 3 E and F). Next, we measured Δψm with the voltage-dependent indicators JC-1 and TMRE, which decrease the intensity of mitochondrial fluorescence upon IMM depolarization (27). Compared with scrambled shRNA-transfected controls, cells (on glycolytic media) transfected with c-subunit shRNA had similar starting Δψm (Fig. S5A), cytosolic ATP levels (Fig. S5B), and cell survival (MTT assay, n = 24 wells per condition). Ionomycin decreased Δψm in both untransfected control cells and those transfected with scrambled shRNA but not after treatment with 2 µM CsA or depletion of ATP5G1 (Fig. S5 C and D). Together, these data suggest that the c-subunit is necessary for rapid IMM permeabilization and membrane depolarization induced by PT.

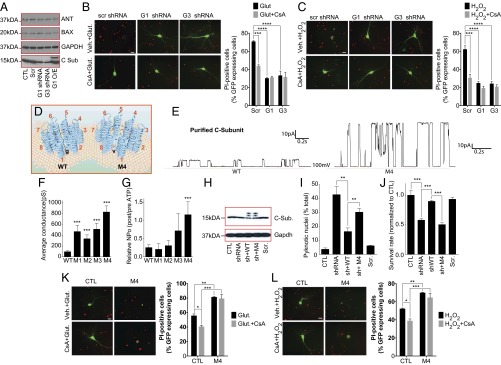

Fig. 4.

Altering c-subunit expression or packing regulates IMM conductance and sensitivity to excitotoxic and ROS-mediated cell death. (A) Immunoblot using the indicated antibodies. (B and C) Images and group data of propidium iodide (PI) staining of cultured hippocampal neurons at 24 h after 30-min exposure to 100 µM glutamate or 20 µM H2O2 with or without 0.5 µM CsA (n ≥ 3 independent cultures, 56–65 micrographs of each condition; G1, ATP5G1; G3, ATP5G3). (D) Schematic of the WT and M4 c-subunit rings. Increased channel conductance of M4 mutant suggests decreased packing and a larger central pore due to the Gly-Val mutation. (E) Representative patch clamp recordings of liposomes reconstituted with WT or M4 c-subunit. (F) Peak single channel conductance for liposome recordings with the indicated protein (WT, n = 38; M1, n = 7; M2, n = 17; M3, n = 7 M4, n = 22; ***P < 0.0001 for WT vs. M1–M4). (G) Normalized NPO before and after addition of 1 mM ATP to patches with the indicated protein (WT, n = 21; M1, n = 3; M2, n = 6; M3, n = 5; M4, n = 8; ***P = 0.0009 comparing WT to M4 ATP response, NPO, number of channels multiplied times the probability of opening of each channel). (H) Immunoblot using the indicated antibodies. The uppermost bands labeled with anti–c-subunit antibody represent the myc/FLAG tagged overexpressed protein. The lower bands have lost one of the tags (blot is representative of >5 blots). (I and J) Percent pyknotic nuclei (I) and cell survival (MTT assay) (J), measured in HEK 293T cells expressing the indicated constructs (n = 2 experiments with three coverslips, two fields per coverslip per condition (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.0001). Measurements were made 24 h after switching to galactose-containing, glucose-free medium. (K and L) Images and group data of PI staining of hippocampal neurons at 18 h after 30-min exposure to 100 µM glutamate or 20 µM H2O2 with vehicle or 0.5 µM CsA (n = 3 independent cultures, 38–53 micrographs of each condition. (Scale bars: B, C, K, and L, 20 µm.) *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Depletion of the C-Subunit Attenuates, Whereas Overexpression of Mutant Large Conductance C-Subunit Aggravates, Cell Death.

Because PT is the hallmark of certain forms of cell death, particularly after ischemia in brain and heart (28, 29), we tested whether c-subunits were required for Ca2+- and H2O2-induced death. We found that, as previously reported, CsA attenuated H2O2- or glutamate-induced death in cultured hippocampal neurons (Fig. 4 B and C). In addition, although depletion of ATP5G1 or ATP5G3 by shRNA did not affect protein levels of Bax or ANT (Fig. 4A), it attenuated H2O2- or glutamate-induced death to a similar extent to that of CsA (Fig. 4 B and C). These studies suggest that c-subunit expression is required for excitotoxicity and reactive oxygen species (ROS)-associated cell death.

To further demonstrate that the c-subunit ring creates an uncoupling pore, we mutated four highly conserved glycines within the first (N terminus) alpha-helical region of the c-subunit (Fig. S6). These glycines may be responsible for the tight packing of the c-subunit molecules within the ring structure and control membrane coupling and OXPHOS (Fig. 4D) (30–32). To decrease this tight packing, we made four individual constructs containing glycine-to-valine mutations (M1–M4), and all four mutant proteins when reconstituted into liposomes demonstrated increased single-channel conductance averaging over multiple traces (including those with subconductance states only) compared with WT c-subunit; the conductance of M4 was the largest of the four (Fig. 4 E and F). We also found that M4 abolished attenuation of channel activity by ATP (Fig. 4G). Because these changes in the c-subunit ring could decrease metabolic efficiency and thus increase cell death, we determined whether the mutations altered cell survival by combining intrinsic c-subunit depletion with overexpression of shRNA-resistant WT and M4 constructs (Fig. 4H). After depletion of c-subunits, forcing OXPHOS using glucose-free, galactose-containing medium increased cell death whereas overexpression of the WT, but not M4, c-subunit rescued these effects (Fig. 4 I and J). Therefore, we overexpressed M4 c-subunit in neurons and determined effects on H2O2- or glutamate-induced cell death in normal medium. Neuronal death was markedly increased in cells overexpressing M4, and this death was not inhibited by CsA (Fig. 4 K and L). These data demonstrate that mutations that loosen the packing of c-subunits of ATP synthase permanently increase the conductance of the c-subunit ring, decrease sensitivity to CsA and ATP, and increase cell death under oxidative conditions or in response to PT-inducing stimuli.

F1 Is Required for Inhibition of C-Subunit Channel Activation, and FO Releases F1 During PT.

Because our previous studies suggested that the F1 beta-subunit may control leak current (12, 13) and other studies suggested that F1 removal uncouples bacterial membranes (33), we hypothesized that positioning of F1 over the c-subunit ring may be required for adequate coupling and inhibition of the c-subunit leak conductance. To detect whether components of F1 bind to and inhibit the c-subunit channel, we applied purified individual F1 proteins to reconstituted c-subunit channels (Fig. 5A). Although gamma-, delta-, and epsilon-subunits had no effect, purified beta-subunit protein attenuated the c-subunit conductance in both the small and large conductance modes (Fig. 5 B–D), suggesting that the beta-subunit can bind to the c-subunit directly to inhibit pore activity in vitro.

Our findings that removal of the F1 proteins with urea unmasked, and adding back the beta-subunit inhibited, the conductance of the c-subunit pore raised the intriguing possibility that physical uncoupling of F1 from FO could increase c-subunit pore conductance and initiate PT. Therefore, we determined whether release of F1 from c-subunit rings was associated with PT. Indeed, using immunocapture of the whole ATP synthase (experimental design in Fig. S7), Ca2+-induced swelling released c-subunit oligomers (15 kDa, 120 kDa, and 250 kDa) seen in denaturing or native immunoblots whereas PT inhibitors (CsA, ADP) prevented the release from ATP synthase (Fig. 5 E, G, and H). Furthermore, c-subunit release was not detectable in mitochondria from CypD KO mice, even when swelling was induced with very high concentrations of Ca2+ (Fig. 5 F and G) (22). This release of c-subunits was not due to mitochondrial rupture because insignificant amounts of c-subunit were found in the postmitochondrial supernatant after Ca2+-induced swelling, which, in contrast, did release cytochrome c (Fig. S8). These data suggest that CypD-mediated Ca2+ binding to F1 destabilizes ATP synthase, causing unmasking of the c-subunit ring, which initiates PT (Figs. 5I and Fig. S7B).

Discussion

Mitochondrial PT was first described in the 1950s (10) whereas the electrophysiologic properties of the mPTP (or MCC) were described in the 1980s and 1990s as a voltage- and Ca2+-sensitive multiconductance channel (conductances from 100 pS to 2 nS (1, 19–21)). mPTP is inhibited by CsA and ADP. We find similar biophysical features in the purified c-subunit, yet it is not sensitive to Ca2+ and it is resistant to CsA. However, the original recordings of MCC/mPTP used preparations of IMM or mitoplasts that contain now appreciated regulatory components such as CypD, and we recapitulate the data of these reports using SMVs and purified ATP synthase. Thus, we conclude that the major regulatory sites for the mPTP, which provide sensitivity to Ca2+, CypD, CsA, and ADP, reside in F1. These sites are removed during purification of the c-subunit or by stripping F1 from FO using urea, exposing a lower-affinity adenine nucleotide binding site (Figs. 1 and 2 and Figs. S1 and S3). Furthermore, the purified c-subunit ring largely lacks cation selectivity, similar to the MCC. For these reasons, we suggest that the c-subunit ring is the pore of the mPTP.

If the c-subunit comprises the mPTP, then there exists a relationship between the opening of the mPTP and ATP synthase activity. If the mPTP is open, ATP hydrolysis, rather than synthesis, occurs, leading to a rundown of energy and further opening of the mPTP. In addition, eliminating the c-subunit may disrupt assembly and function of ATP synthase, compromising metabolism in cells that depend on OXPHOS (Fig. 4 H–J). However, glycolytic conditions prevent this toxicity unless stress occurs (excitotoxicity, H2O2) (Fig. 4 and Fig. S5). Overall, too much pore activity will prevent ATP production and too little mPTP activity, although enhancing the efficiency of OXPHOS, could be detrimental to cell survival by preventing an escape valve for Ca2+ and ROS.

In summary, we find that the long-sought molecular pore of the mPTP is a heretofore-undetected ion channel located within the c-subunit ring of the mammalian ATP synthase that may be exposed during physical uncoupling of the F1 and FO complexes. Depletion of the c-subunit prevents mitochondrial PT, attenuating excitotoxicity- and ROS-induced death in primary neurons. Mutations of the transmembrane domain that loosen c-subunit packing increase the size of the c-subunit channel conductance and predispose cells to death in a CsA-resistant manner. The c-subunit channel is inhibited by the beta-subunit of ATP synthase, regulated also by Bcl-xL to improve metabolism (12). From a pathophysiologic standpoint, induction of PT unmasks c-subunit rings that create the mPTP. We suggest that the c-subunit ring is so situated as to regulate both metabolism and death.

Materials and Methods

Purification of the F1FO ATP Synthase Subunit Proteins and C-Subunit Knockdown.

Cells were transfected to express or knock down (shRNA) WT or mutant human ATP5G1 or -3.

Electrophysiology.

SMV, mitochondrial, or proteoliposome recordings were made by forming a giga-ohm seal in intracellular solution. Group data were quantified in terms of conductance.

Bipartite Tetracysteine Display.

Two cysteine residues were placed on the N terminus of the c-subunit sequence before the first alpha-helical region (on the intermembraneous space side).

Statistical Analysis.

Data in graphs are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons included t tests or ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis tests with post hoc testing (P < 0.05).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Leonard K. Kaczmarek for insightful scientific discussion and constructive review of the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant NS064967 (to E.A.J.) and American Heart Association Grant 12GRNT12060233 (to G.A.P.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Commentary on page 10396.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1401591111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Petronilli V, Szabò I, Zoratti M. The inner mitochondrial membrane contains ion-conducting channels similar to those found in bacteria. FEBS Lett. 1989;259(1):137–143. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81513-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonenko YN, Smith D, Kinnally KW, Tedeschi H. Single-channel activity induced in mitoplasts by alkaline pH. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1194(2):247–254. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernardi P, et al. Modulation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore: Effect of protons and divalent cations. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(5):2934–2939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernardi P. Modulation of the mitochondrial cyclosporin A-sensitive permeability transition pore by the proton electrochemical gradient: Evidence that the pore can be opened by membrane depolarization. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(13):8834–8839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jonas EA, Buchanan J, Kaczmarek LK. Prolonged activation of mitochondrial conductances during synaptic transmission. Science. 1999;286(5443):1347–1350. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hüser J, Blatter LA. Fluctuations in mitochondrial membrane potential caused by repetitive gating of the permeability transition pore. Biochem J. 1999;343(Pt 2):311–317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hom JR, et al. The permeability transition pore controls cardiac mitochondrial maturation and myocyte differentiation. Dev Cell. 2011;21(3):469–478. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haworth RA, Hunter DR. Control of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore by high-affinity ADP binding at the ADP/ATP translocase in permeabilized mitochondria. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2000;32(1):91–96. doi: 10.1023/a:1005568630151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kokoszka JE, et al. The ADP/ATP translocator is not essential for the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Nature. 2004;427(6973):461–465. doi: 10.1038/nature02229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernardi P. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore: A mystery solved? Front Physiol. 2013;4:95. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elrod JW, Molkentin JD. Physiologic functions of cyclophilin D and the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Circ J. 2013;77(5):1111–1122. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-13-0321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alavian KN, et al. Bcl-xL regulates metabolic efficiency of neurons through interaction with the mitochondrial F1FO ATP synthase. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(10):1224–1233. doi: 10.1038/ncb2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen YB, et al. Bcl-xL regulates mitochondrial energetics by stabilizing the inner membrane potential. J Cell Biol. 2011;195(2):263–276. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonora M, et al. Role of the c subunit of the FO ATP synthase in mitochondrial permeability transition. Cell Cycle. 2013;12(4):674–683. doi: 10.4161/cc.23599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giorgio V, et al. Dimers of mitochondrial ATP synthase form the permeability transition pore. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(15):5887–5892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217823110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chinopoulos C, Szabadkai G. What makes you can also break you: Mitochondrial permeability transition pore formation by the c subunit of the F(1)F(0) ATP-synthase? Front Oncol. 2013;3:25. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watt IN, Montgomery MG, Runswick MJ, Leslie AG, Walker JE. Bioenergetic cost of making an adenosine triphosphate molecule in animal mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(39):16823–16827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011099107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Havlícková V, Kaplanová V, Nůsková H, Drahota Z, Houstek J. Knockdown of F1 epsilon subunit decreases mitochondrial content of ATP synthase and leads to accumulation of subunit c. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797(6-7):1124–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zorov DB, Kinnally KW, Perini S, Tedeschi H. Multiple conductance levels in rat heart inner mitochondrial membranes studied by patch clamping. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1105(2):263–270. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(92)90203-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szabó I, Zoratti M. The mitochondrial megachannel is the permeability transition pore. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1992;24(1):111–117. doi: 10.1007/BF00769537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szabó I, Bernardi P, Zoratti M. Modulation of the mitochondrial megachannel by divalent cations and protons. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(5):2940–2946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baines CP, et al. Loss of cyclophilin D reveals a critical role for mitochondrial permeability transition in cell death. Nature. 2005;434(7033):658–662. doi: 10.1038/nature03434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakagawa T, et al. Cyclophilin D-dependent mitochondrial permeability transition regulates some necrotic but not apoptotic cell death. Nature. 2005;434(7033):652–658. doi: 10.1038/nature03317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luedtke NW, Dexter RJ, Fried DB, Schepartz A. Surveying polypeptide and protein domain conformation and association with FlAsH and ReAsH. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3(12):779–784. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffmann C, et al. A FlAsH-based FRET approach to determine G protein-coupled receptor activation in living cells. Nat Methods. 2005;2(3):171–176. doi: 10.1038/nmeth742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams SR, et al. New biarsenical ligands and tetracysteine motifs for protein labeling in vitro and in vivo: Synthesis and biological applications. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124(21):6063–6076. doi: 10.1021/ja017687n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicholls DG. Fluorescence measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential changes in cultured cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;810:119–133. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-382-0_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown DA, O’Rourke B. Cardiac mitochondria and arrhythmias. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;88(2):241–249. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crompton M. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore and its role in cell death. Biochem J. 1999;341(Pt 2):233–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norris U, Karp PE, Fimmel AL. Mutational analysis of the glycine-rich region of the c subunit of the Escherichia coli F0F1 ATPase. J Bacteriol. 1992;174(13):4496–4499. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.13.4496-4499.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pogoryelov D, et al. The oligomeric state of c rings from cyanobacterial F-ATP synthases varies from 13 to 15. J Bacteriol. 2007;189(16):5895–5902. doi: 10.1128/JB.00581-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vonck J, et al. Molecular architecture of the undecameric rotor of a bacterial Na+-ATP synthase. J Mol Biol. 2002;321(2):307–316. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00597-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitome N, Suzuki T, Hayashi S, Yoshida M. Thermophilic ATP synthase has a decamer c-ring: Indication of noninteger 10:3 H+/ATP ratio and permissive elastic coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(33):12159–12164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403545101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.