Abstract

Objective:

To assess the prevalence of medication and nutritional supplement use in male Football Super League players and to observe the long term changes of players’ attitudes during 5 years period (4 seasons).

Study Design:

Retrospective study.

Material and Methods:

Review and analysis of 4176 doping control forms -declaration reports- about players’ medication intake including; Super League, UEFA Cup and the UEFA Champions League matches. Team physician was asked to document all medications and nutritional supplements taken by the Football Super League players in the last 72 hours before each match.

Results:

A total intake of 5939 substances were documented, of which almost half 49.2% (n=2921) were classified as medications and 50.8% (n=3018) were nutritional supplements. The average consumption per player was 1.42 substance/match; 0.70 were medications and 0.72 of nutritional supplements. The supplements used most frequently were NSAIDs 24.6% (n=1460) accounting for almost one in four of all reported supplements. Diclofenac Sodium was the most frequently reported active pharmaceutical ingredient. Second most frequently used supplements were vitamins (22.2%). The average drug consumption reported per player has been increasing every passing year. It was 0.7 substance/match/player (0.4 medication; 0.3 nutritional supplement) in 2003–2004 season; was increased to 1.8 substance/match (0.8 medication; 1.0 nutritional supplement) in 2006–2007 season.

Conclusion:

The trends seen in this survey point to an overuse of NSAIDs and vitamins in comparison with other medications, amoung Turkish Super League football players (p<0.001). The use of NSAIDs has increased but the medication groups did not differ significantly between seasons, in terms of distribution. This increasing use of medications especially of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and nutritional supplements is alarming and needs to be argued.

Keywords: Permitted medications, nutritional supplements, doping

Introduction

Sports, especially the football is one of the most popular entertainment areas for the people having lots of stress in today’s difficult life routine. The use of medication and nutritional supplements have always been a highlight in the world of sports but argued mainly from the aspect of doping for about five decades since the Federation Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) introduced doping and doping controls in football. On the other hand only very limited studies exist about permitted drug use in sports. The permitted and not permitted use of drugs in sports, especially amoung the ones requiring high physical endurance and performance, is taking more attention day by day. FIFA has a clear vision for its anti-doping strategy in football; make the game doping free. But the main principles in sport concern not only equality and fairness but also health of people doing sports in other words to protect the players from harm as FIFA declared (1, 2). In this view, many literature had focused on doping substances, medications not permitted to use in sports. On the other hand, very limited literature had focused on prescribed substances such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and nutritional supplements (3–5). Only a few study are available on professional football players, mostly because access to large numbers of elite players is restricted, and elite players are generally reluctant to discuss their habits (6). One study conducted on Italian professional soccer players reported data on permitted drug usage during one season, and other study conducted on English professional soccer players reported data on supplement and vitamin use in a selected sample of subjects (6, 7). One study conducted on the World Cups 2002 and 2006 reported data on permitted drug usage during these two football tournaments (8).

As such, the investigation and control of the unnecessary and overuse of permitted, legally prescribed medications should be as important as the drugs not permitted. Because these medications -when used in high doses- have a potential to be harmful. More than 20.000 doping controls are performed annually on football players as a result of the colloborative effort between FIFA and regional confederations and the overall incidence of positive doping samples for prohibited substances accounts for only 0.4% of all tests (9). FIFA, the Union of the Europian Football Association (UEFA), and some of the national anti-doping organisations also perform out of competition controls at training venues during the football season (10).

The objective of this study was to gather data on permitted medication and nutritional supplement use in Turkish professional football Super League players during 5 years period, in order to create a realistic picture of their use and more importantly to be able to see the picture of the players’ changing attitudes about the use of medications and nutritional supplements over 5 years interval between 2003 and 2008.

Material and Methods

Data collection

Data included in the present study were acquired in connection with the doping controls carried out in the Turkish Football League and in the UEFA Leagues (Table 1). Each player and the team physician were asked to declare any medication taken by the players or administered to them in the 72 hours preceding each match.

Table 1.

Distribution of matches and numbers of players doping control forms

| Number of matches (n1) and players doping control forms (n2) | Season 2003–2004 | Season 2004–2005 | Season 2005–2006 | Season 2006–2007 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n1 | n2 | % | n1 | n2 | % | n1 | n2 | % | n1 | n2 | % | |

| Preparation matches | 8 | 144 | 17.4 | 11 | 198 | 19.0 | 11 | 198 | 18.3 | 14 | 252 | 20.6 |

| European Cups | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 144 | 13.8 | 6 | 108 | 10.0 | 12 | 216 | 17.6 |

| Turkish Cup matches | 4 | 72 | 8.7 | 5 | 90 | 8.6 | 9 | 162 | 15.0 | 8 | 144 | 11.8 |

| Turkish Super league | 34 | 612 | 73.9 | 34 | 612 | 58.6 | 34 | 612 | 56.7 | 34 | 612 | 50.0 |

| Total | 46 | 828 | 100.0 | 58 | 1044 | 100.0 | 60 | 1080 | 100.0 | 68 | 1224 | 100.0 |

n1=Number of matches,

n2=Number of doping control forms

Data analysed in this study were acquired from the reports declared to the concerning doping committee for each player in the squad (18 players each). A total of 4176 declaration reports (a report/player) from a total of 232 matches studied during 2003–2004; 2004–2005; 2005–2006 and 2006–2007 seasons, including the; Super League, UEFA Champions League, UEFA Cup, Turkish Cup matches and also the preparation matches (Table 1).

Data presentation

The incidence of substance intake was calculated as follows:

Pharmaceutical ingredients

Based on the information provided by the team physician, the active pharmaceutical ingredient of each reported substance was identified, and the substance was classified as one of the following (11):

Medications, one of the two main used substance groups, were classified into sub-groups as; anti-inflammatory drugs (This group was studied separately from pain killer drugs in order to be able to emphasize the consumption of NSAIDs), pain killer drugs, injections (This group was studied separately from other drug groups in order to be able to emphasize the parenteral use of drugs), muscle relaxants, antimicrobial medications, medications for the Respiratory System, medications for the Gastro-intestinal System and other medications (Table 2).

Table 2.

Classification of the used drugs and supplements

| Medications | Anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Pain killer drugs | |

| Injections | |

| Muscle relaxants | |

| Antimicrobial medication | |

| Medications for the Respiratory System | |

| Medications for the Gastro-intestinal System | |

| Others | |

| Nutritional Supplements | Vitamins |

| Minerals | |

| Amino Acids | |

| Creatine | |

| L-Carnitine | |

| Herbal and Homeopathic Supplements | |

| Others |

Nutritional Supplements, second main substance group used, were also classified into sub-groups; Vitamins, Minerals, Amino Acids, Creatine, L-Carnitine, Herbal and Homeopathic Supplements and others (Table 2).

Data Analysis

In the analysis, medications and nutritional supplements have dealt with separately. The data were analyzed using frequencies and cross-tabulations. Chi-square tests were used for comparison of medication and nutritional supplement categories. The level of significance was taken as 0.05.

Results

In these 4 seasons, a total intake of 5.939 substances were documented, of which almost half 2921 (49.2%) were classified as medications (Table 2) and 3018 (50.8%) were nutritional supplements (Table 3).

Table 3.

Use of medications according to the football seasons

| Medications | Season 2003–2004 | Season 2004–2005 | Season 2005–2006 | Season 2006–2007 | P value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| NSAID’s | 148 | 46.8 | 311 | 49.2 | 426 | 49.9 | 575 | 51.3 | >0.05 |

| Injections | 20 | 6.4 | 36 | 5.7 | 52 | 6.1 | 65 | 5.8 | >0.05 |

| Analgesic | 34 | 10.8 | 62 | 9.8 | 73 | 8.6 | 88 | 7.9 | >0.05 |

| Muscle Relaxant | 41 | 12.9 | 70 | 11.1 | 109 | 12.8 | 152 | 13.5 | >0.05 |

| Respiratory Agents | 7 | 2.2 | 11 | 1.7 | 19 | 2.2 | 17 | 1.5 | >0.05 |

| Gastrointestinal Agents | 20 | 6.4 | 58 | 9.2 | 61 | 7.2 | 85 | 7.6 | >0.05 |

| Antimicrobial Agents | 31 | 9.8 | 52 | 8.2 | 75 | 8.7 | 88 | 7.9 | >0.05 |

| Others | 15 | 4.7 | 32 | 5.1 | 38 | 4.5 | 50 | 4.5 | >0.05 |

| Total | 316 | 100.0 | 632 | 100.0 | 853 | 100.0 | 1120 | 100.0 | |

Comparison of rates of drug use according to seasons

The average permitted drug consumption per player was 1.42 substance/match. The average medication use per game by each player was 0.70 and similarly, the average nutritional supplement us eper game by each player was 0.72.

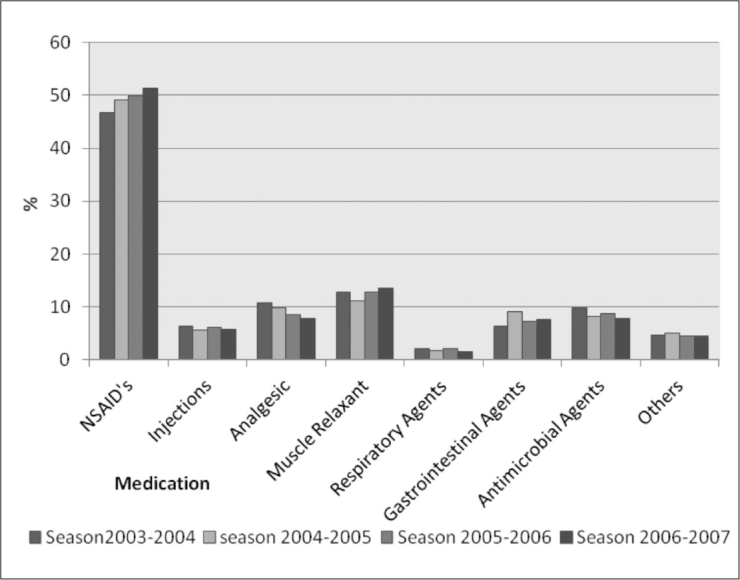

NSAIDs were the most frequently prescribed substances, accounting for almost one in four of all reported medicines used (2003–2004: 26%, 2004–2005: 24%, 2005–2006: 24.5%, 2006–2007: 24.8%) and half (49.9%) of all reported medications used (2003–2004: 46.8%, 2004–2005: 49.2%, 2005–2006: 49.9%, 2006–2007: 51.3%).

Diclofenac Sodium was the most frequently reported active pharmaceutical ingredient.

A total intake of 3018 nutritional substances were documented, of which vitamins represented the majority with slightly less than half of the total intake of nutritional supplements: 1319 (43.7%). Besides vitamins, 572 (19%) were minerals: 555 (18.4%) were homeopathic and herbal supplements (Table 4).

Table 4.

Use of nutritional supplements according to the football seasons

| Nutritional Supplements | Season 2003–2004 | Season 2004–2005 | Season 2005–2006 | Season 2006–2007 | p value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Vitamins | 110 | 41.7 | 308 | 45.8 | 375 | 42.9 | 526 | 43.6 | >0.05 |

| Minerals | 56 | 21.2 | 126 | 18.7 | 170 | 19.4 | 220 | 18.2 | >0.05 |

| Herbal and Homeopathic | 44 | 16.6 | 112 | 16.5 | 164 | 18.7 | 235 | 19.5 | >0.05 |

| Aminoacids | 32 | 12.1 | 73 | 10.9 | 92 | 10.5 | 118 | 9.9 | >0.05 |

| Creatine | 10 | 3.8 | 24 | 3.6 | 36 | 4.2 | 42 | 3.5 | >0.05 |

| L-Carnitine | 7 | 2.7 | 18 | 2.7 | 24 | 2.7 | 35 | 2.8 | >0.05 |

| Others | 5 | 1.9 | 12 | 1.8 | 14 | 1.6 | 30 | 2.5 | >0.05 |

| Total | 100 | 100.0 | 673 | 100.0 | 875 | 100.0 | 1206 | 100.0 | |

Comparison of rates of drug use according to seasons

2003–2004 Season

The average consumption per player was 0.7 substance/match (0.4 medication; 0.3 nutritional supplement) prior to each match during 2003–2004 season (Figure 1). A total in-take of 580 substances were documented, of which more than half 316 (54.5%) were classified as medications (Table 3) and 264 (45.5%) were nutritional supplements (Table 4). Some individual players took as many as four different substances or three of the seven different substance groups prior to a match at maximum. On average 3 players use at least one substance/match. Nearly 70% of the players use at least one substance and more than half of the players (66%) took NSAIDs at least once during 2003–2004 season. On average, NSAIDs used by 2 players/match. More than 10% of the players taking NSAIDs were using at least two substances, in some as many as four different substances were taken.

Figure 1.

Use of medications according to the football seasons

2004–2005 Season

The average consumption was sharply increased to 1.25 substance/player/match (0.60 medication; 0.65 nutritional supplement) prior to each match during 2004–2005 season (Tables 3, 4). A total intake of 1305 substances were documented, of which slightly less than half 632 (48.4%) were classified as medications and 673 (51.5%) were nutritional supplements. Some individual players took as many as five different substances or four of the seven different substance groups prior to a match at maximum. On average 5 players use at least one substance/match. Nearly 80% of the players use at least one substance and 75% of the players took NSAIDs at least once during 2003–2004 season. On average, NSAIDs used by 3 players/match. More than 20% of the players taking NSAIDs were using at least one more substance, in some as many as five different substances were taken.

2005–2006 Season

The average consumption per player was increased to 1.6 substance/match (0.79 medication; 0.81 nutritional supplement) prior to each match during 2005–2006 season (Figure 1). A total intake of 1728 substances were documented, of which almost half 853 (49.3%) were classified as medications and 875 (50.6%) were nutritional supplements. Some individual players took as many as five different substances or four of the seven different substance groups prior to a match at maximum. On average 6 players use at least one substance/match. Nearly 85% of the players use at least one substance and 80% of the players took NSAIDs at least once during 2005–2006 season. On average, NSAIDs used by 4 players/match. More than 25% of the players taking NSAIDs were using at least one more substance, in some as many as five different substances were taken.

2006–2007 Season

The average consumption per player was continued to increase to 1.8 substance/match (0.8 medication; 1.0 nutritional supplement) prior to each match during 2006–2007 season (Tables 3, 4). A total intake of 2326 substances were documented, of which 1120 (48.2%) were classified as medications and 1206 (51.7%) were nutritional supplements. Some individual players took as many as six different substances or five of the seven different substance groups prior to a match at maximum. On average 7 players use at least one substance/match. Nearly 88% of the players use at least one substance and 82% of the players took NSAIDs at least once during 2006–2007 season. On average, NSAIDs used by 4 players/match. More than 33.3% of the players taking NSAIDs were using at least one more substance, in some as many as five different substances were taken.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics

NSAIDs were the most frequently prescribed substances, accounting for almost one in four of all reported substances used (2003–2004: 26%, 2004–2005: 24%, 2005–2006: 24.5%, 2006–2007: 24.8%) and half (49.9%) of all reported medications used (2003–2004: 46.8%, 2004–2005: 49.2%, 2005–2006: 49.9%, 2006–2007: 51.3%) More than 80% of the players took NSAIDs at least once during a season and. Most of the players took NSAIDs at least once (2003–2004: 66%, 2004–2005: 75%, 2005–2006: 80%, 2006–2007: 82%) during a football season and 24.8% prior to a match. On average, NSAIDs used by 4 players/match. (2003–2004: 2 players/match, 2004–2005: 3 players/match, 2005–2006: 4 players/match, 2006–2007: 4 players/match).

More than 25% of the players taking NSAIDs were using at least two preparations prior to a match (2003–2004: 10%; 2004–2005: 20%, 2005–2006: 25%, 2006–2007: 33.3%); in some players, as many as five different preparations were taken. Diclofenac was the most frequently reported active pharmaceutical ingredient (2003–2004: 146, 2004–2005; 305, 2005–2006: 400, 2006–2007: 510),almost 22% of all pharmaceutical ingredients followed by Ketoprofen (4%). Acetylsalicylic acid was rarely reported 0.9%. Other analgesics represented 4.4% of all prescribed medicines.

Other medications

Corticosteroids, accounting for 3% of all medications, were mainly injected and used as ointments (66.5%). Other medical indications, such as for ears and eyes (23.5%), respiratory tract and gastrointestinal problems were less frequent.

In nearly 1/3 of the cases, gastric protectors such as proton pump inhibitors, prostaglandins and others were reported in combination with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Substances acting primarily on the upper and lower respiratory tract were one of the least frequently prescribed substances (2003–2004: 1.2%, 2004–2005: 1%, 2005–2006 1.1%; 2006–2007: 0.75%), with antihistamines being the most common of these, accounting for 52.5%, antitussives 17.5%, followed by β2–agonists 11.7%, inhaled corticosteroids 9.2%, and others 9%.

Nutritional supplements

The average consumption of the nutritional supplements was 0.72 substance/player/match. prior to each match during 2004–2005 season (Figure 1). A total intake of 3018 substances were documented, of which vitamins represented the majority with slightly less than half: 1319 (43.7%): 572 (19%) were minerals: 555 (18.4%) were Homeopathic and herbal supplements: 315 (10.5%) were aminoacids: 112 (3.7%) were creatine products: 84 (2.7%) were L-carnitine products and 61 (2%) were other nutritional supplements. Some individual players took as many as 6 different substances or four of the seven different substance groups prior to a match at maximum. On average 5 players use at least one substance/match. Nearly 80% of the players use at least one substance and 75% of the players took NSAIDs at least once during 2003–2004 season. On average, NSAIDs used by 3 players/match. More than 20% of the players taking NSAIDs were using at least one more substance, in some as many as five different substances were taken.

Iron supplementation represented 9.8% of the prescribed minerals substantially less than the mineral complexes 58.2% and magnesium 25.5%. Of the amino acids, polyamino-acids were represented the majority with more than half (52.2%) followed by arginine (22.6%) and glutamine (21.2%).

Combined preparations were the most often used herbal and homeopathic substances, most of which containing Ginseng supplementation (68.4%); preparations containing guarana (14.7%) and arnica (10.5%) were rarely used compared to ginseng.

Discussion

The use of medications and nutitional supplements has been increasing significantly in sports at large, and it is perhaps not suprising that professional football players reflect this trend (12). Although, in absolute terms, the number of controls carried out in football is relatively large, the fact that there is also a large number of professional players means that professional footballers are tested for drugs much less frequently than are most other elite athletes (9). During the doping control of a choosen match, only 2 players choosen from the team squad in general practice. In other words doping controllers could be able to test approximately 10% of the players of the team. The study conducted on English professional soccer players indicated that, on average, only about one third of professional footballers will be tested in any given year and this compares unfavourably with the situation in many other sports (7).

The substantial variations in the previous studies’ reported medication use, especially with respect to NSAIDs, highlight the difference in therapeutic concepts and also the different affinities to the use of nutritional supplements that currently exists in sports medicine. The majority are most likely based on individual empirical evidence or experience rather than on any firm evidence base.

Most of the studies performed has been about the substances which were not permitted to use in sports. From the few studies about the permitted drug use in football, previous study of Italian professional soccer players found that 92.6% of players reported having used oral anti-inflammatory drugs in a year, and most of them were current users 86.1%. Besides the medications about one from each three Italian players reported using vitamins (6). Another study on English professional football players found that many players use supplements to enhance their performance and 45% of players personally knew other players who used recreational drugs (7). Study conducted on the World Cups 2002 and 2006 reported a high intake of medication in international football, average drug consumption found was 1.8 substances/player/match (42.9% of which were medicinal and 57.1% were nutritional supplements) during these two tournaments (8). About other sports, a study of athletes participating in the Olympic Games 2000 in Sydney found that 80% of athletes declared using some sort of medication (13). A mean intake of 4.6 dietary supplements per player, prescribed medications and over-the-counter substances were reported for Canadian athletes (14). Recently published data on medication use in professional footballers indicate a high intake of both supplements7 and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (7–15).

The present study was able to document the prevalence of long term medication use in a Football Super League Team in Turkey during 5 years period. This long term documentation had also given us a chance to be able to see the yearly changes of players attitudes about the permitted drug use. However our study was not able to scrutinise the underlying motivations for such use or the likely implications of such changes in the players attitudes about the drug use.

Also the relationship between team success and the amount or type of prescribed medication was not issued in this study.

The present results show a widespread use of prescribed medicines in professional football, with 1.42 substances per player per match being reported. NSAIDs represented nearly 25% of all substances, with one in four players being prescribed NSAIDs prior to a match, on average 4 players per match. More than 25% of the players taking NSAIDs were using at least two preparations prior to a match and some taking as many as seven different preparations.

Players with a high average playing time were prescribed more medications and more NSAIDs per match than were substitutes.

A wide range was reported for nutrititonal supplement use (24 different supplements), with as many as 11 different substances being taken prior to a match in some cases.

Some previous studies have analysed the use of prescription medicines in different areas of sports, such as; in athletes during the Olympic Games (OG), in National Olympic squads participating in winter and summer sports and in professional soccer players in England and in Italy during one season (6, 7, 13, 16). The present study differs from all of the previous studies in this field about the use of permitted drugs with the duration, data were collected prior to every match during 5 years (4 football seasons).

Compared with the information acquired during the doping controls In professional football players in Italy, however, 86% were reported to be current NSAIDs users (6). Although there are reports of a high prevalence of sustained adverse effects with NSAID use in athletes, the indication for NSAIDs appears to have been broadened to almost any painful condition (16, 17).

National Health Service recommends lowest possible dose for shortest possible period referring the use of NSAIDs and they also recommend to avoid the use of additional preparations with NSAIDs (18). According to the results of the studies in the literature, it looks like these therapeutic recommendations have not yet been adopted in sports. In the present study, more than one in ten players taking NSAIDs were using at least two preparations, NSAIDs were used 7.5 times more frequently than other analgesics, 24.8% of all players used NSAIDs before their matches.

Respiratory system medications were rarely prescribed in international football as seen in previous studies (8–13).

The results of the present survey also showed a widespread use of prescribed nutritional substances in professional football. Nearly half of all reported substances were the nutritional supplements (50.8%). A total intake of 3018 nutritional substances were documented, of which vitamins represented the majority with slightly less than half: 1319 (43.7%). Besides vitamins, 572 (19%) were minerals: 555 (18.4%) were homeopathic and herbal supplements.

Although there are different opinions about the use nutritional supplements, almost all agree at the point that nutritional supplementation is not so necessary with an “adequate” diet (19). Therefore, professional advice from a physician on the quality and quantity and also the necessary types and dosages of supplementation according to the players’ needs is essential.

Although incidence of doping seems to be low, the use of permitted medications and nutritional supplements is quite high in todays football. But this study, in addition to this result which was also shown by previous studies, points to an additional finding that the use of mentioned medications and supplements tend to increase each year.

This is one of the first long term study about this subject on professional elite football players, giving idea about the changes of the players attitudes on “legally” prescribed drug usage and strikingly picturing the alarming situation in the use of permitted drugs spesifically NSAIDs and nutritional supplements. The results raise questions as to whether the medication was taken only for therapeutic reasons. In view of the potential side effects, more restrictive recommendations and controls for sports especially for football may needs to be argued and revised.

The strength of our study is the difficulty to interpret the long term data -high intake of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and nutritional supplements- reported during this 5 years period in elite football players. One of the limitations of our study is that we did not objectively quantify the dosages of actual consumption.

We see this as an important warning in today’s football industry, strikingly picturing the alarming increase in the use of permitted drugs, spesifically NSAIDs and nutritional supplements. And also as a warning to alert sport physicians as well as sport administrators and doping committees who must understand the current situation and develop strategies and approaches to this problematic area of particular urgency.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: Ethics committee approval was received for this study.

Informed Consent: N/A.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author contributions: Concept - E.K.; Design - E.K.; Supervi sion -E.K.; Resource - E.K.; Materials - E.K.; Data Collec tion&/or Processing - E.K.; Analysis&/or Interpretation - M.K.B., Literature Search - E.K.; Writing - E.K.; Critical Reviews -E.K.; M.K.B.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Financial Disclosure: No financial disclosure was declared by the authors.

References

- 1.Blatter JS. FIFA’s commitment to doping free football. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:i1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dvorak J, Graf-Baumann T, D’Hooghe M, Kirkendall D, Taennler H, Saugy M. FIFA’s approach to doping in football. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(Suppl I):i3–12. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.027383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paoloni JA, Orchard JW. The use of therapeutic medications for soft-tissue injuries in sports medicine. MJA. 2005;183:384–8. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker J, Cotter JD, Gerrard DF, Bell ML, Walker RJ. Effects of indomethacin and celecoxib on renal function in athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37:712–7. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000162700.66214.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwenk TL, Costley CD. When food becomes a drug:nonanabolic nutritional supplement use in athletes. Am J Ortho Soc Sports Med. 2002;30:907–16. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300062701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taioli E. Use of permitted drugs in Italian professional soccer players. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:439–41. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.034405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waddington I, Malcolm D, Roderick M, Naik R. Drug use in English professional football. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:e18. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.012468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tscholl PM, Junge A, Dvorak J. The use of medication and nutritional supplements during FIFA World Cups 2002 and 2006. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42:725–30. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.045187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dvorak J, McCrory P, D’Hooghe M. FIFA’s future activities in the fight against doping. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:i58–9. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.027771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Regulations - Doping Control for FIFA Competitions and Out of Competition. Accessed at: http://de.fifa.com/mm/document/afdeveloping/medical/6.17.%20fifa%20doping%20control%20regulations_1533.pdf, on January 10, 2012.

- 11.Tscholl P, Alonso JM, Dollé G, Junge A, Dvorak J. The use of drugs and nutritional supplements in top-level track and field athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:133–40. doi: 10.1177/0363546509344071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thuyne WV, Delbeke FT. Declared use of medication in sports. Clin J Sport Med. 2008;18:143–7. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e318163f220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corrigan B, Kazlauskas R. Medication Use in Athletes Selected for Doping Control at the Sydney Olympics (2000) Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13:33–40. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200301000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang SH, Johnson K, Pipe AL. The use of dietary supplements and medications by Canadian athletes at the Atlanta and Sydney Olympic Games. Clin J Sport Med. 2006;16:27–33. doi: 10.1097/01.jsm.0000194766.35443.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alaranta A, Alaranta H, Holmila J, Palmu P, Pietilä K, Helenius I. Self-reported attitudes of elite athletes towards doping:differences between type of sport. Int J Sports Med. 2005;27:842–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-872969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alaranta A, Alaranta H, Heliövaara M, Airaksinen M, Helenius I. Ample use of physician-prescribed medications in Finnish elite athletes. Int J Sports Med. 2006;27:919–25. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-923811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dieppe PA, Ebrahim S, Martin RM, Jüni P. Lessons from the withdrawal of rofecoxib. BMJ. 2004;329:867–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7471.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NHS Guidelines. Accessed at http://www.cks.nhs.uk/CksContent/TopicReview/PreviousVersions/nonsteriodal_anti_inflammatory_drugs.pdf, on January 14, 2012.

- 19.Burke L, Deakin V. Nutritional Supplements in Clinical Sports Nutrition. Sydney: McGraw-Hill Australia; 2006. [Google Scholar]