Abstract

Rumination is a well-established risk factor for the onset of major depression and anxiety symptomatology in both adolescents and adults. Despite the robust associations between rumination and internalizing psychopathology, there is a dearth of research examining factors that might lead to a ruminative response style. In the current study, we examined whether social environmental experiences were associated with rumination. Specifically, we evaluated whether self-reported exposure to stressful life events predicted subsequent increases in rumination. We also investigated whether rumination served as a mechanism underlying the longitudinal association between self-reported stressful life events and internalizing symptoms. Self-reported stressful life events, rumination, and symptoms of depression and anxiety were assessed in 2 separate longitudinal samples. A sample of early adolescents (N = 1,065) was assessed at 3 time points spanning 7 months. A sample of adults (N = 1,132) was assessed at 2 time points spanning 12 months. In both samples, self-reported exposure to stressful life events was associated longitudinally with increased engagement in rumination. In addition, rumination mediated the longitudinal relationship between self-reported stressors and symptoms of anxiety in both samples and the relationship between self-reported life events and symptoms of depression in the adult sample. Identifying the psychological and neurobiological mechanisms that explain a greater propensity for rumination following stressors remains an important goal for future research. This study provides novel evidence for the role of stressful life events in shaping characteristic responses to distress, specifically engagement in rumination, highlighting potentially useful targets for interventions aimed at preventing the onset of depression and anxiety.

Keywords: rumination, stress, internalizing symptoms, depression, anxiety

Rumination involves repetitive and passive focus on the causes and consequences of one’s symptoms of distress without engagement in active coping or problem solving to alleviate dysphoric mood (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). Numerous studies suggest that the tendency to ruminate is associated prospectively with increases in depressive symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema & Davis, 1999; Nolen-Hoeksema, Larson, & Grayson, 1999;Nolen-Hoeksema, Morrow, & Frederickson, 1993; Nolen-Hoeksema, Parker, & Larson, 1994), heightened risk for new onsets of major depression (Abela & Hankin, 2011; Just & Alloy, 1997; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Robinson &Alloy, 2003), and greater chronicity of depressive episodes (Robinson & Alloy, 2003). Rumination is also associated with elevated risk for anxiety symptomology (Fresco, Frankel, Mennin, Turk, & Heimberg, 2002; Harrington & Blankenship, 2002; Mellings & Alden, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991). In addition, experimentally inducing rumination in distressed individuals prolongs both depressed and anxious mood compared with inducing distraction (Blagden & Craske, 1996; McLaughlin, Borkovec, & Sibrava, 2007; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1993).

Despite the fact that rumination is among the most robust risk factors for depression and anxiety (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010), we know very little about the factors that predict the development of a ruminative response style. Identifying such factors would not only improve our understanding of the etiology of a ruminative response style but also have important implications for designing preventive interventions. One factor that may increase engagement in rumination is the experience of stress, that is, social and environmental circumstances that require psychological and physiological adaptation over time by the organism (Monroe, 2008). The stress process involves a dynamic interaction between the organism and environment that changes over time in response to external challenges, perceptions of those challenges, and the coping resources that are activated following social and environmental challenges (Monroe, 2008). Conceptual models regarding the etiology of rumination argue that the experience of stressful life events might lead to rumination not only about those events but also about many areas of an individual’s life (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1994; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1999). The current report examines this possibility.

Control theories (Carver & Scheier, 1981; Martin & Tesser, 1996) provide the most direct explanation for how stressful experiences might lead to rumination (cf. Watkins, 2008). Negative events can create discrepancies between goals or desired states and one’s current state and lead to rumination about how to reduce such discrepancies (Carver & Scheier, 1981; Martin & Tesser, 1996). For example, receiving an unexpectedly low grade on a term paper may create a discrepancy with a student’s goal of doing well in a course, which in turn leads to rumination about this discrepancy. If the rumination leads to resolution of the discrepancy (e.g., the student decides the course is too difficult and decides to drop it), then the rumination will stop. If the discrepancy cannot be resolved, the individual may continue to ruminate about it. Uncontrollable or chronic stressors may be especially likely to lead to rumination because they create discrepancies between the individual’s current state and his or her goals or desired states (e.g., happiness) that cannot be resolved (Watkins, 2008). Indeed, one study of bereaved adults found that those who reported greater chronic stress showed increased rumination over time (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1994). Similarly, in an experience sampling study of individuals facing stigma-related stressors due to race or sexual orientation, engagement in rumination was higher on days when stigma-related stressors were experienced (Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Dovidio, 2009).

Stress may also induce rumination by undermining self-regulation, or the capacity to engage in self-control over one’s behavior (Baumeister, Gailliot, DeWall, & Oaten, 2006; Inzlicht, McKay, & Aronson, 2006). Limited regulatory abilities may impair an individual’s ability to engage in problem solving or active coping and increase the likelihood of engagement in rumination. Indeed, various studies have shown that active coping strategies such as problem solving are negatively correlated with rumination (see review by Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008). A variety of other cognitive mechanisms might also increase the likelihood of rumination following stressful life events, including attention to negative thoughts and feelings, autobiographical memory for previous negative events, and negative self-schema activation (Scher, Ingram, & Segal, 2005; Segal & Ingram, 1994).

Slavich’s psychobiological theory of depression (Slavich, O’Donovan, Epel, & Kemeny, 2010) provides an additional conceptual framework linking experiences of stress—particularly interpersonal stressors involving social rejection—to engagement in rumination. This theory proposes that social rejection stressors elicit a coordinated pattern of cognitive, emotional, and neurobiological responses that culminate in heightened risk for depression (Slavich, O’Donovan, et al., 2010). In particular, social rejection is associated with activation in brain regions involved in emotional awareness and emotion regulation (Beauregard, Lévesque, & Bourgouin, 2001; Lane et al., 1998; Ochsner & Gross, 2005; Slavich, Way, Eisenberger, & Taylor, 2010; Somerville, Heatherton, & Kelley, 2006) that are activated during self-reflection (Johnson et al., 2006). Thus, brain regions that are sensitive to social rejection stressors are also centrally involved in the core self-reflective process that underlies rumination, suggesting a potential neurobiological mechanism linking interpersonal stressors to increased engagement in rumination.

Like rumination, stressful life events consistently predict the onset of major depression and anxiety disorders (Brown, 1993; Hammen, 2005; Kendler, Hettema, Butera, Gardner, & Prescott, 2003; Kendler, Karkowski, & Prescott, 1999), and it is possible that rumination represents a mechanism that explains the relationship between stress exposure and the onset of internalizing psychopathology. Early studies with individuals who had experienced stressors such as a natural disaster (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991) or bereavement (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1994) found that those who were prone to ruminate had more severe and longer periods of negative mood following these events than those not prone to ruminate. However, these studies did not directly examine rumination as a mechanism linking stress to internalizing symptoms. More recently, evidence from an experience sampling study suggested that engagement in rumination partially mediates the association between negative life events and negative affect (Moberly & Watkins, 2008). Similarly, rumination was found to mediate the relationship between stigma-related stressors and psychological distress (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009). Yet, the extent to which rumination explains the association between stressful events and symptoms of psychopathology is not well understood.

The purpose of the current study was twofold: (a) to examine the role of self-reported stressful life events as a predictor of changes in rumination over time, and (b) to determine whether rumination is a mechanism linking self-reported stressful life events to subsequent increases in symptoms of depression and anxiety. We expected that self-reported stress exposure would be associated prospectively with increases in rumination, such that individuals reporting greater stress exposure would show greater increases in rumination over time than those reporting less stress exposure. We additionally predicted that increases in rumination following self-reported exposure to stress would mediate the relationship between reported stressful life events and increases in symptoms of depression and anxiety over time. To evaluate these hypotheses, we examined the association between self-reported stressful life events, rumination, and symptoms of depression and anxiety in two longitudinal studies: one using a school-based sample of early adolescents and one based on a community sample of adults. Finally, given substantial gender differences in rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991) and in the prevalence of symptoms of depression and anxiety beginning in adolescence (Hankin et al., 1998;Nolen-Hoeksema & Girgus, 1994; Twenge & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002), we examined whether the relationships between self-reported stressful life events, rumination, and symptoms of depression and anxiety varied by gender.

Study 1

Method

Participants and procedure

Adolescents were recruited from the total enrollment of two middle schools (Grades 6–8) in central Connecticut that agreed to participate in the study, excluding students in self-contained special education classrooms and technical programs who did not attend school for the majority of the day. The schools were located in a small urban community (metropolitan population of 71,538). Schools were selected for the study on the basis of demographic characteristics of the school district and their willingness to participate.

The parents of all eligible children (N = 1,567) in the participating middle schools were asked to provide active consent for their children to participate in the study. Parents who did not return written consent forms to the school were contacted by telephone. Twenty-two percent of parents did not return consent forms and could not be reached to obtain consent, and 6% of parents declined to provide consent. Adolescent participants provided written assent. The overall participation rate in the study at baseline was 72%.

The baseline sample included 51.2% (n = 545) boys and 48.8% (n = 520) girls. Participants were evenly distributed across grade level (mean age = 12.2 years, SD = 1.0). The race/ethnicity composition of the sample was as follows: 13.2% (n = 141) non-Hispanic White, 11.8% (n = 126) non-Hispanic Black, 57.3% (n = 610) Hispanic/Latino, 2.3% (n = 24) Asian/Pacific Islander, 0.2% (n = 2) Native American, 0.8% (n = 9) Middle Eastern, 9.4% (n = 100) biracial/multiracial, and 4.2% (n = 45) other racial/ethnic groups. Several students (n = 8, 0.8%) did not provide information on race/ethnicity. Twenty-seven percent (n = 293) of participants reported living in single-parent households. The participating middle schools reside in a predominantly lower socioeconomic status community, with a per capita income of $18,404 (Connecticut Department of Education, 2006, based on data from 2001). School records indicated that 62.3% of students qualified for free or reduced lunch in the 2004–2005 school year. There were no differences across the two schools in demographic variables.

Two additional assessments took place after the baseline assessment. Of the participants who were present at baseline, 221 (20.8%) did not participate at the Time 2 assessment, and 217 (20.4%) did not participate at the Time 3 assessment, largely due to transient student enrollment in the district. Over the 4-year period from 2000 to 2004, 22.7% of students had left the school district (Connecticut Department of Education, 2006). Participants who completed the baseline but not both follow-up assessments (n = 1,065) were more likely to be girls, χ2(1) = 6.85, p < .01, but did not differ in grade level, race/ethnicity, or being from a single-parent household (ps > .10). Participants who did not complete at least one of the follow-up assessments did not differ from participants who completed all three assessments on levels of rumination or symptoms of depression or anxiety symptoms at baseline (ps > .10).

Participants completed study questionnaires during their homeroom period. All questionnaires used in the present analyses were administered at Time 1 and Time 3, and the rumination measure was additionally administered at Time 2. Four months elapsed between the Time 1 (November 2005) and Time 2 (March 2006) assessments, and 3 months elapsed between Time 2 and Time 3 (June 2006) assessments. This timeframe was chosen to allow the maximum time between assessments to observe changes in internalizing symptoms while also ensuring that all assessments occurred within the same academic year to avoid high attrition. Participants were assured of the confidentiality of their responses and the voluntary nature of their participation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Yale University.

Measures

Self-reported stressful life events

The Life Events Scale for Children (Coddington, 1972) is composed of 25 items, each of which represents a stressful life event (e.g., “Your parents got divorced” and “You got suspended from school”). Participants are asked to indicate which events they had experienced in the prior 6 months. Life events checklists are the most commonly used instruments to assess adolescent stress (Grant, Compas, Thurm, & McMahon, 2004). Good test–retest reliability over 1- to 2-week intervals has been reported for life event checklists in adolescents (Cohen, Burt, & Bjork, 1987; Compas, 1987), as well as convergent validity with maternal reports of exposure to stressful life events in young adolescents (Cohen et al., 1987) and roommate reports in older adolescents (Compas, 1987).

Rumination

The Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire (CRSQ; Abela, Brozina, & Haigh, 2002) is a 25-item scale that assesses the extent to which children respond to sad feelings with rumination (defined as self-focused thought concerning the causes and consequences of depressed mood), distraction, or problem solving. The measure is modeled after the Response Styles Questionnaire (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991) that was developed for adults. For each item, youths are asked to rate how often they respond in that way when they feel sad on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). The Rumination subscale includes 13 items that are summed to generate a score ranging from 13 to 42. Sample items include “Think about a recent situation wishing it had gone better” and “Think ‘Why can’t I handle things better?’” The reliability and validity of the CRSQ have been demonstrated in samples of early adolescents (Abela et al., 2002). The CRSQ rumination scale demonstrated good reliability in this study (α = .86).

Depressive symptoms

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992) is a widely used self-report measure of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. The CDI includes 27 items consisting of three statements (e.g., “I am sad once in a while,”“I am sad many times,”“I am sad all the time”) representing different levels of severity of a specific symptom of depression. The CDI has sound psychometric properties, including internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and discriminant validity (Kovacs, 1992; Reynolds, 1994). The item pertaining to suicidal ideation was removed from the measure at the request of school officials and the human subjects committee. The 26 remaining items were summed to create a total score ranging from 0 to 52. The CDI demonstrated good reliability in this sample (α = .82).

Anxiety symptoms

The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, 1997) is a 39-item measure of child anxiety. The MASC assesses physical symptoms of anxiety, harm avoidance, social anxiety, and separation anxiety and is appropriate for children ages 8 to 19 years. Each item presents a symptom of anxiety, and participants indicate how true each item is for them on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never true) to 3 (very true). A total score, ranging from 0 to 117, is generated by summing all items. The MASC has high internal consistency and test–retest reliability across 3-month intervals and established convergent and divergent validity (Muris, Merckelbach, Ollendick, King, & Bogie, 2002). The MASC demonstrated good reliability in this sample (α = .88).

Data analysis

Structural equation modeling was used to perform all analyses in MPlus software (Muthén & Muthén, 1998). Analyses were conducted using the full information maximum likelihood estimation method, which estimates means and intercepts to handle missing data. Multiply indicated latent variables were created for depression, anxiety, and rumination using three methods: (1) including scale items as observed variables; (2) creating parcels of items using the domain representative approach, such that each parcel included items from each of the subscales of the relevant measures (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002); and (3) creating parcels of items using the within-domain approach, such that each parcel included items from one and only one of the subscales of each measure. We compared these three methods because the value of using parcels to model constructs as latent factors remains debated. Although using parcels as opposed to an observed variable representing a total scale score confers a number of psychometric advantages including greater reliability, reduced error variance, and increased efficiency (Coffman & MacCallum, 2005; Kishton & Widaman, 1994; Little et al., 2002), there are also limitations to parceling. Drawbacks include the possibility of model misspecification if constructs are multidimensional and items load onto an additional latent factor that is not included in the model and reduced interpretability of scales that have established norms (Little et al., 2002). Because the field has not reached consensus regarding the use of parcels or the most advantageous method for constructing parcels, we compared these three approaches to determine which provided the best fit to our data. Subscales used to create parcels were drawn from the established lower order factors of each construct based on prior research and exploratory factor analysis in our data. Subscales of rumination included brooding, reflection, and dysphoria (Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003); subscales of depressive symptoms included internalizing (dysphoria, self-deprecation, and social problems) and externalizing (school problems and aggression/disobedience) dimensions (Craighead, Smucker, Craighead, & Ilardi, 1998); and subscales of anxiety symptoms included physical symptoms, social anxiety, harm avoidance, and separation anxiety (March et al., 1997).

After comparing the three measurement models, each of which included all latent constructs modeled simultaneously, we conducted analyses to examine the role of rumination as a mediator of the longitudinal associations between self-reported stressful life event exposure and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Standard tests of statistical mediation were employed. We first examined each of the steps in the mediation pathway: (1) the association between Time 1 self-reported life events and Time 3 symptoms of depression and anxiety, controlling for symptom levels at Time 1; (2) the association between self-reported life events at Time 1 and rumination at Time 2, controlling for Time 1 rumination; (3) the association between Time 2 rumination and Time 3 symptoms, controlling for Time 1 symptoms and rumination; and (4) the attenuation in the association between self-reported stressful life events at Time 1 and symptoms at Time 3 after accounting for changes in rumination from Time 1 to Time 2. We tested the significance of the mediator using a bootstrapping approach that provides confidence intervals around the indirect effect (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Confidence intervals that do not include zero indicate significant mediation. This analysis provides a stringent test of mediation, which allowed us to investigate whether Time 1 self-reported stressful life events predicted changes in rumination and whether those changes predicted subsequent increases in symptoms of depression and anxiety. Multigroup analyses were conducted to examine whether the process of mediation was moderated by gender. Each of the mediation paths was constrained to be equal for boys and girls, and the difference in model fit was examined using a chi-square test. Finally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine whether the longitudinal association between stressful life events at Time 1 and rumination at Time 2 was driven entirely by those individuals with high rumination at Time 1. We evaluated this possibility by examining whether Time 1 stressful life events interacted with Time 1 rumination to predict Time 2 rumination.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 displays the means and standard deviations of all measures at each time point, separately for boys and girls. Girls reported higher levels of rumination and symptoms of depression and anxiety than boys; no gender difference was observed in the number of self-reported stressful life events. Table 2 provides the zero-order correlations among self-reported stressful life events, rumination, and symptoms of depression and anxiety. As expected, rumination was positively associated with depression and anxiety symptoms, which were positively associated with one another. Self-reported stressful life events were associated positively with rumination and with symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Stressful Life Events, Rumination, and Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety

| Measure | Total sample

|

Males

|

Females

|

Gender difference t | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Adolescent sample | |||||||

| Stressful life events | 5.10 | 3.33 | 5.09 | 3.47 | 5.12 | 3.19 | t(999)=0.15 |

| Time 1 CRSQ rumination | 10.94 | 7.65 | 9.40 | 7.12 | 12.53 | 7.84 | t(1045)=6.77* |

| Time 1 CDI depression | 9.67 | 6.44 | 9.11 | 6.37 | 10.25 | 6.47 | t(1052)=2.87* |

| Time 1 MASC anxiety | 40.19 | 15.39 | 36.67 | 14.98 | 43.95 | 14.95 | t(1058)=7.92* |

| Time 2 CRSQ rumination | 10.84 | 7.65 | 8.72 | 6.66 | 12.24 | 8.17 | t(835)=6.85* |

| Time 3 CRSQ rumination | 10.18 | 8.07 | 8.25 | 7.31 | 11.43 | 8.35 | t(830)=5.83* |

| Time 3 CDI depression | 10.63 | 8.15 | 9.70 | 8.18 | 10.73 | 7.74 | t(852)=1.90* |

| Time 3 MASC anxiety | 34.80 | 18.05 | 31.64 | 18.51 | 37.49 | 17.22 | t(853)=4.79* |

| Adult sample | |||||||

| Stressful life events | 1.98 | 1.77 | 1.85 | 1.73 | 2.09 | 1.79 | t(1325)=2.55* |

| Time 1 RSQ rumination | 1.88 | 0.48 | 1.82 | 0.45 | 1.91 | 0.49 | t(1325)=3.65* |

| Time 1 BDI depression | 4.58 | 4.35 | 4.11 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 4.60 | t(1325)=3.74* |

| Time 1 BAI anxiety | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.38 | t(1241)=4.00* |

| Time 2 RSQ rumination | 38.81 | 10.23 | 37.35 | 9.51 | 40.05 | 10.65 | t(1130)=4.47* |

| Time 2 BDI depression | 3.97 | 4.08 | 3.51 | 3.83 | 4.35 | 4.25 | t(1131)=3.50* |

| Time 2 BAI anxiety | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.35 | t(1131)=5.00* |

Note. CRSQ = Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire; CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory; MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; RSQ = Response Styles Questionnaire; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory.

Significant at the .01 level, 2-sided test.

Table 2.

Correlations Between Stressful Life Events, Rumination, and Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent sample | ||||||||

| 1. LES-C stressful life events | — | |||||||

| 2. CRSQ rumination Time 1 | .18** | — | ||||||

| 3. CDI depression Time 1 | .29** | .42** | — | |||||

| 4. MASC anxiety Time 1 | .10** | .55** | .28** | — | ||||

| 5. CRSQ rumination Time 2 | .18** | .57** | .39** | .43** | — | |||

| 6. CRSQ rumination Time 3 | .16** | .48** | .35** | .41** | .48** | — | ||

| 7. CDI depression Time 3 | .20** | .23** | .54** | .13** | .33** | .44** | — | |

| 8. MASC anxiety Time 3 | .14** | .35** | .24** | .53** | .44** | .69** | .33** | — |

| Adult sample | ||||||||

| 1. HDL stressful life events | — | |||||||

| 2. RSQ rumination Time 1 | .27** | — | ||||||

| 3. BDI depression Time 1 | .21** | .50** | — | |||||

| 4. BAI anxiety Time 1 | .24** | .46** | .60** | — | ||||

| 5. RSQ rumination Time 2 | .24** | .67** | .44** | .38** | — | |||

| 6. BDI depression Time 2 | .14** | .37** | .60** | .47** | .50** | — | ||

| 7. BAI anxiety Time 1 | .20** | .39** | .50** | .63** | .46** | .61** | — |

Note. LES-C = Life Events Scale for Children; CRSQ = Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire; CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory; MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; HDL = Health and Daily Living Form; RSQ = Response Styles Questionnaire; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory.

Significant at the .01 level, 2-sided test.

Measurement models

Three measurement models were tested, each of which included latent variables for adolescent depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and rumination. Of the three approaches to constructing the latent variables, only the domain representative approach (using four parcels for each of the three constructs) provided a good fit to the data. All fit indices indicated that the measurement model fit the data well: χ2(51) = 173.8, p < .001; comparative fit index (CFI) = .98; Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = .98; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .05 (90% CI [.04, .06]). The model constructed using within-domain parcels (three parcels for rumination, two for depression, and four for anxiety) did not fit the data well, χ2(24) = 332.0, p < .001; CFI = .99; TLI = .99; RMSEA = .10 (90% CI [.90, .10]), nor did the model constructed using observed variables, χ2(2846) = 8480.7, p < .001; CFI = .69; TLI = .68; RMSEA = .04 (90% CI [.04, .04]).

Stressful life events and rumination

Self-reported exposure to stressful life events was associated with rumination at Time 2, controlling for Time 1 rumination, β = .08, p = .007. The relationship between stressful life events and rumination at Time 2 remained significant after additional controls for internalizing symptoms at Time 1 were added to the model, β = .07, p = .030.

Longitudinal mediation analyses

After documenting a prospective association between self-reported stress exposure and engagement in rumination, we examined the role of rumination as a mediator of the longitudinal associations between self-reported stressors and symptoms of depression and anxiety. We examined two longitudinal mediation models, one predicting depression and one predicting anxiety.

Self-reported exposure to stressful life events at Time 1 was marginally associated with depressive symptoms at Time 3, controlling for Time 1 depression, β = .06, p = .053. As noted above, Time 1 self-reported life events were associated with Time 2 rumination, controlling for rumination at Time 1. Time 2 rumination was associated with Time 3 depressive symptoms, controlling for Time 1 symptoms and rumination, β = .19, p < .001. In the final mediation model, Time 1 self-reported stressful life events were not associated significantly with Time 3 depressive symptoms, controlling for Time 1 depression and rumination, when Time 2 rumination was added to the model, β = .03, p = .393. The indirect effect of self-reported life events on depressive symptoms through rumination was not statistically significant (point estimate = .01; 95% CI [−.01, .03]). The final mediation model accounted for the covariance between symptoms of depression, rumination, and self-reported life events. Fit indices indicated that the model fit the data well: χ2(112) = 420.7, p < .001; CFI = .97; TLI = .96; and RMSEA = .05 (90% CI [.04, .05]).

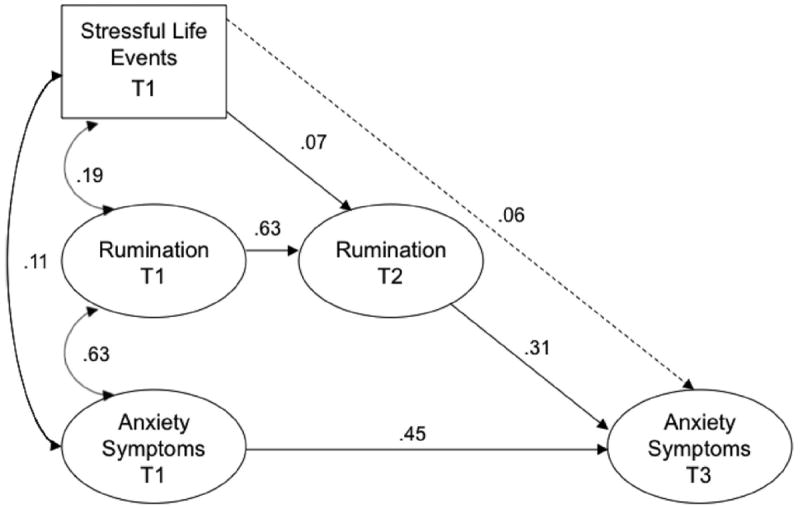

Self-reported exposure to stressful life events at Time 1 was associated with anxiety symptoms at Time 3, controlling for Time 1 anxiety, β = .10, p = .002. Time 2 rumination was associated with Time 3 anxiety symptoms, controlling for Time 1 symptoms and rumination, β = .37, p < .001. In the final mediation model, Time 1 self-reported stressful life events were no longer associated significantly with Time 3 anxiety symptoms, controlling for Time 1 anxiety and Time 1 rumination, when Time 2 rumination was added to the model, β = .06, p = .183 (see Figure 1), and the indirect effect of self-reported stressful life events on anxiety through rumination was statistically significant (point estimate = .12; 95% CI [.02, .24]). The covariance between symptoms of anxiety, rumination, and self-reported stressful life events was accounted for in the final model. Fit indices indicated that the model fit the data well: χ2(112) = 332.7, p < .001; CFI = .98; TLI = .98; and RMSEA = .04 (90% CI [.03, .04]).

Figure 1.

Final mediation model for anxiety symptoms in the adolescent sample. Numbers represent standardized path coefficients (β). All paths shown are significant (p < .05), except those drawn with broken lines. All constructs were modeled as latent variables other than stressful life events. Given space constraints, indicator variables are not displayed.

Moderation by gender

Finally, we examined whether the role of rumination as a mediator of the relationship between stressful life events and changes in internalizing symptoms was moderated by gender. When the mediation paths of interest (see Figure 1) were constrained to equivalence across male and female adolescents, the model fit did not significantly worsen for depression, χ2(3) = 1.53, p = .68, or anxiety, χ2(3) = 3.43, p = .33.

Sensitivity analysis

We examined whether self-reported stressful life events interacted with rumination at Time 1 to predict rumination at Time 2 to evaluate whether the association between self-reported stressful life events and later rumination was driven entirely by those individuals with high rumination at Time 1. This interaction was not significant, β = .04, p = .396, indicating that changes in rumination following self-reported stressful life events did not occur only among those with high levels of rumination at Time 1.

Discussion

Study 1 results indicate that self-reported exposure to stressful life events is associated with increased engagement in rumination over time in adolescents. Self-reported stress at Time 1 predicted increases in rumination at a 4-month follow-up, suggesting lasting changes in the degree to which participants were engaging in rumination following a self-reported stressful life event. Findings further indicate that increases in rumination, in turn, significantly mediated the relationship between self-reported stress exposure and subsequent increases in anxiety over a 7-month period. Although a similar pattern of findings emerged regarding the role of rumination as a mediator of the association between self-reported stressors and changes over time in depressive symptoms, the indirect effect was not statistically significant. We observed no gender differences in the role of rumination as a mechanism linking self-reported stressful life events to internalizing symptoms in adolescents.

Study 2

Method

Participants and procedure

Adults living in the greater San Francisco Bay Area were recruited using random-digit-dial telephone calls to households in San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland, California. These specific communities were chosen to increase the racial/ethnic diversity of the sample. One adult from the household was recruited for the study. Participants provided written informed consent.

Of the 1,789 individuals identified as eligible for participation, 1,317 completed a baseline interview (22.6% declined participation and 3.7% agreed to participate but did not return calls to schedule the interview). The mean age was 47.0 years old (SD = 15.2) and the proportion female was 45.5%. The racial/ethnic composition of the sample was as follows: 72% non-Hispanic White, 9% Hispanic/Latino, 7% Black, 6% Asian/Pacific Islander, and 6% multiracial or other race/ethnicity. The majority of the sample (54%) was married or cohabiting, 18% were single, 16% were separated or divorced, 9% were widowed, and 3% were in a committed relationship but not cohabiting. The sample was diverse in regards to educational attainment, with 19% of respondents having a high school degree or less education, 27% with some college, 26% with a college degree, 8% with some postgraduate education, and 21% with a graduate or professional degree. The median income of the sample in 1994 was $40,000 to $50,000.

Of the 1,317 baseline respondents, 1,132 (85.9%) completed a second interview 1 year later. Respondents who did not complete a second interview had significantly higher interview-rated and self-reported depressive symptoms than respondents who completed both interviews (p < .05). The analyses include only the 1,132 respondents who completed both interviews.

Respondents were interviewed in person by an extensively trained clinical interviewer at both the baseline interview and follow-up interview 1 year later. Most interviews were conducted in the respondents’ homes. Interviews lasted approximately 90 min. Interviewers read the instructions aloud to the respondent for each measure and recorded the responses. Respondents were given a card with response options for all items that required the use of a Likert scale or involved a choice between groups of possible answers. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Stanford University.

Measures

Stressful life events

We used a revised version of the Stressful Life Circumstances Index of the Health and Daily Living Form (Moos, Cronkite, Billings, & Finney, 1986) to evaluate stress in adults. The original index consists of 42 items that each describes an undesirable life change event (e.g., “Serious illness or injury of a family member” and “Divorce”). Respondents are asked to indicate which events they, or someone close to them, had experienced during the previous 6 months. Six of the 42 items are specific to women. We revised the original index by removing 10 items that were inconsistent with our definition of stressful life events (i.e., undesirable social and environmental events requiring adaptation by the respondent). Items that were removed included events that would likely be experienced by most as positive and not require significant adaptation (e.g., “Income increased substantially [20%]”) or experiences that captured qualities of the respondent’s behavior rather than social or environmental events (e.g., “Alcohol or drug problems”). The remaining 32 items were summed to calculate a total life events score. Only events that happened directly to the respondent in the previous 6 months were included in the total score. Adequate test–retest reliability has been found for this measure over a 6-month period (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1994).

Rumination

The Response Styles Questionnaire (RSQ; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991) was administered to assess participants’ tendencies to ruminate in response to dysphoric mood. The Ruminative Responses scale of the RSQ includes 22 items describing responses that are self-focused (e.g., “I think, ‘Why do I react this way?’”), symptom focused (e.g., “I think about how hard it is to concentrate”), and focused on the possible consequences and causes of negative mood (e.g., “I think, ‘I won’t be able to do my job if I don’t snap out of this’”). Respondents rate each item on a scale from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). The Ruminative Responses scale demonstrated good internal consistency in this sample (α = .90). Scores on this scale ranged from 22 to 76 at baseline and from 22 to 75 at the follow-up. Previous studies have documented acceptable convergent and predictive validity of this scale (Butler & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1994; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991).

Depression

Participants completed the 13-item form of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck & Beck, 1972), a self-report measure of current depressive symptoms. The BDI is one of the most widely used self-report instruments for detecting depressive symptoms. The BDI demonstrated good internal consistency in this sample (α = .82). Scores on the BDI ranged from 0 to 29 at baseline and from 0 to 26 at the follow-up. A meta-analysis of the psychometric properties of the BDI documented good internal consistency and test–retest reliability across intervals ranging up to 1 month, as well as excellent convergent and discriminant validity (Beck, Steer, & Carbin, 1988).

Anxiety

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck & Steer, 1990) was used to assess anxiety symptoms. The BAI has 21 items assessing the severity of anxiety symptoms using a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (severely/could barely stand it). Beck and Steer (1991) reported strong concurrent validity of the BAI with clinical ratings of anxiety. The BAI demonstrated good internal consistency in this sample (α = .88). Scores on the BAI ranged from 0 to 52 at baseline and from 0 to 41 at the follow-up.

Data analysis

We followed the same procedures for constructing the latent variables and testing the measurement models as described in Study 1. Subscales of rumination included brooding, reflection, and dysphoria (Treynor et al., 2003); subscales of depressive symptoms included somatic-affective and cognitive (Steer, Ball, Ranieri, & Beck, 1999); and subscales of anxiety symptoms included neurophysiological, subjective, panic, and autonomic (Osman, Kopper, Barrios, Osman, & Wade, 1997).

Because the adult sample included only two time points, we followed the procedure for evaluating mediation in a half-longitudinal design (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). Specifically, we examined (a) the association between Time 1 self-reported stressful life events and Time 2 symptoms of depression and anxiety, controlling for Time 1 symptoms; (b) the association between stressful life events at Time 1 and rumination at Time 2, controlling for Time 1 rumination; (c) the association between Time 1 rumination and Time 2 symptoms of depression and anxiety, controlling for Time 1 symptoms; and (d) the attenuation in the association between self-reported stressful life events at Time 1 and Time 2 symptoms of depression and anxiety after accounting for rumination at Time 1. The significance of the indirect effect was tested using the standard bootstrapping method (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Multigroup analysis to test moderation and sensitivity analysis were conducted using the same procedures as in Study 1.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 displays the means and standard deviations of all measures at each time point, separately for men and women. Higher levels of rumination, symptoms of depression and anxiety, and stressful life events were reported by women compared with men. Table 2 provides the zero-order correlations among self-reported stressful life events, rumination, and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Rumination was positively associated with depression and anxiety symptoms, which were positively associated with one another. Self-reported stressful life events were associated positively with rumination and with symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Measurement models

Three measurement models were tested, each of which included latent variables for depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and rumination. Of the three approaches to construct the latent variables, only the domain representative approach (using four parcels for each of the three constructs) fit the data well: χ2(51) = 215.9, p < .001; CFI = .98; TLI = .98; RMSEA = .05 (90% CI [.04, .06]). Poor model fit was observed for the model constructed using within-domain parcels (three parcels for rumination, two for depression, and four for anxiety), χ2(24) = 374.8, p < .001; CFI = .92; TLI = .89; RMSEA = .11 (90% CI [.10, .11]), and the model constructed using observed variables, χ2(1536) = 8405.2, p < .001; CFI = .74; TLI = .73; RMSEA = .06 (90% CI [.06, .06]).

Self-reported stressful life events and rumination

In the adult sample, greater self-reported exposure to stressful life events at Time 1 was associated with greater rumination at Time 2, controlling for rumination at Time 1, β = .06, p = .012. The longitudinal relationship between stressful life events and rumination remained significant even after controls for internalizing symptoms at Time 1 were added to the model, β = .07, p = .032.

Longitudinal mediation models

Self-reported stressful life events at Time 1 were marginally associated with Time 2 depression, controlling for Time 1 depression, β = .05, p = .061. As noted above, self-reported life events were associated longitudinally with rumination. Rumination at Time 1 was associated with Time 2 depressive symptoms, controlling for Time 1 depression, β = .40, p < .001. In the final mediation model, Time 1 self-reported stressful life events were not a significant predictor of Time 2 depressive symptoms, controlling for Time 1 depression, when Time 1 rumination was added to the model, β = .02, p = .217; the covariances between Time 1 self-reported stressful life events, rumination, and symptoms of depression were also modeled. The indirect effect of self-reported stressful life events on depression through rumination was significant (point estimate = .05; 95% CI [.02, .09]). Fit indices indicated that the model fit the data adequately: χ2(112) = 840.4, p < .001; CFI = .95; TLI = .94; and RMSEA = .06 (90% CI [.06, .07]).

We next examined the extent to which rumination mediated the association between self-reported stressful life events and subsequent anxiety symptoms. Stressful life events at Time 1 predicted anxiety symptoms at Time 2, controlling for Time 1 anxiety, β = .06, p = .010. Stressful life events were also associated with rumination at Time 2, as noted above. Rumination at Time 1 was associated significantly with Time 2 anxiety symptoms, controlling for anxiety at Time 1, β = .18, p < .001. In the final mediation model, self-reported stressful life events at Time 1 were no longer a significant predictor of Time 2 anxiety symptoms, controlling for Time 1 anxiety, when Time 1 rumination was added to the model, β = .01, p = .736. The indirect effect of self-reported stressful life events on anxiety through rumination was statistically significant (point estimate = .04; 95% CI [.02, .07]). This model included terms to account for the covariance between Time 1 self-reported stressful life events, rumination, and symptoms of anxiety at Time 1. Fit indices indicated that the model provided adequate fit to the data: χ2(112) = 829.6, p < .001; CFI = .95; TLI = .94; and RMSEA = .07 (90% CI [.06, .07]).

Moderation by gender

No gender differences were observed in the mediating role of rumination in the association between self-reported stressful life events and symptoms of depression, χ2(3) = 3.47, p = .33, or anxiety, χ2(3) = 4.82, p = .19.

Sensitivity analysis

We examined whether self-reported stressful life events interacted with rumination at Time 1 to predict rumination at Time 2 to determine whether the association between self-reported stressful life events at Time 1 and rumination at Time 2 occurred only in individuals with high rumination at Time 1. This interaction was not significant, β = .04, p = .698.

Discussion

In a longitudinal community-based sample of adults, self-reported exposure to stressful life events predicted increases in rumination 1 year later. Heightened rumination was a significant mediator of the association between self-reported stressful life events and subsequent increases in symptoms of both depression and anxiety in adults. The role of rumination as a mediator of the longitudinal association between stressful life events and depression and anxiety symptoms did not vary by gender in adults.

General Discussion

Although rumination is a well-established risk factor for emotional disorders, little is known about vulnerability factors for a ruminative response style. The purpose of this study was first to examine exposure to stressful life events as a vulnerability factor for rumination. As predicted, self-reported stressful life events were associated with increased engagement in rumination over time. Self-reported stressful life events were associated with higher levels of rumination in both adolescents and adults over follow-up periods ranging from several months to a year, suggesting that these life events are associated with changes in depressive rumination that are maintained for prolonged periods of time. The second objective was to determine whether rumination served as a mechanism linking stressful life events to later increases in symptoms of depression and anxiety, and our findings largely support this idea. Rumination was a mediator of the longitudinal association between self-reported stressful life events and anxiety symptoms among adolescents and adults and both males and females. In addition, rumination significantly mediated the relationship between self-reported stressful life events and increases in depressive symptoms in adults, but not in adolescents. Together, these findings highlight the importance of social environmental experiences in shaping responses to distress and the role of rumination as a mechanism underlying stress-related internalizing psychopathology.

Our finding that self-reported stressful life events predicted increases in subsequent engagement in rumination suggests that events perceived as stressful may lead to changes in responses to distress that generalize to many areas of an individual’s life. The measures of rumination used in this study evaluated the degree to which respondents engaged in ruminative responses to feeling sad, down, or dysphoric, rather than engagement in rumination specifically in response to stressors. Given the length of follow-up between our assessment of life events and rumination, the persisting elevation in rumination among those who reported greater exposure to stressful life events suggests a potentially lasting change in characteristic styles of responding to distress. This finding is consistent with a previous study of bereaved adults in which greater stress burden following the death of a loved one was associated with later increases in rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1994).

Why might experiences of stress increase engagement in rumination? A variety of cognitive and neurobiological mechanisms are likely to underlie this relationship. One possible explanation is that negative events increase self-focused rumination as an attempt to reduce discrepancies between goals or desired states and current states (Carver & Scheier, 1981; Martin & Tesser, 1996; Watkins, 2008). Rumination on discrepancies following negative events may persist if it focuses on the causes and/or consequences of those events or on the distress/negative affect associated with stressful events, rather than on actions aimed to resolve the discrepancies (Watkins, 2008). Exposure to stressful life events might also hinder one’s ability to engage in active coping or problem solving (Baumeister et al., 2006; Inzlicht et al., 2006). Specifically, the cognitive and emotional effort required to manage the negative affect elicited by stressful experiences may reduce regulatory resources needed to engage in adaptive coping. Efforts to suppress thoughts about negative events may also increase ruminative thinking (Wenzlaff, Wegner, & Roper, 1988). Stressful life events may also increase attention to negative thoughts and feelings, heighten memory for previous negative events, lead to negative expectations of the future, and activate existing negative self-schemas (Scher et al., 2005; Segal & Ingram, 1994). Activation of negative schemas may be particularly likely when stressors occur in life domains considered central to one’s self-concept (Hammen & Goodman-Brown, 1990). Each of these cognitive processes may contribute to increased engagement in rumination following stressful events.

Finally, exposure to interpersonal stressors, particularly social rejection, activates brain regions that are centrally involved in self-reflection and emotion regulation (Eisenberger, Lieberman, & Williams, 2003; Slavich, Way, et al., 2010; Somerville et al., 2006), including regions involved in emotional awareness (McRae, Reiman, Fort, Chen, & Lane, 2008) as well as in directing attention toward salient environmental cues and monitoring conflict (Botvinick, Cohen, & Carter, 2004; Weissman, Gopalakrishnan, Hazlett, & Woldorff, 2005). As such, activation of these brain regions following interpersonal stressors may result in heightened attention both to the social and environmental changes associated with a negative life event, goal discrepancies associated with these changes, and attention to one’s emotional state. These processes may ultimately result in increased engagement in rumination.

Our findings also suggest that rumination may act as a mechanism linking stress exposure to increases in internalizing psychopathology. In adolescents, rumination served as a mediator between self-reported exposure to stressful life events and increases in anxiety over time, and in adults, rumination mediated the association between self-reported life events and symptoms of both depression and anxiety. Rumination may be more strongly associated with anxiety than depression among early adolescents because they have yet to pass through the period of adolescence associated with greatest risk for onset of depression (Hankin et al., 1998). Previous studies have found that adolescents experiencing a negative event (academic failure or hearing that a parent was diagnosed with cancer) who engaged in more rumination had higher levels of depressed mood than adolescents who did not ruminate (Compas & Grant, 1993; Compas, Malcarne, & Fondacaro, 1988), but these studies did not test rumination as a mediator between negative events and depressed mood. More recently, Moberly and Watkins (2008) found that engagement in rumination partially mediated the association between negative events and negative affect in an experience sampling study. Our results expand on those of Moberly and Watkins, suggesting that rumination serves as a psychological pathway linking negative social environmental experiences to risk for symptoms of anxiety in adolescents and both depression and anxiety in adults. This pattern is similar to results observed recently in another experience sampling study documenting that rumination mediated the association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms among adolescents with low dispositional levels of traits central to mindfulness, including nonreactivity, nonjudgment, and awareness (Ciesla, Reilly, Dickson, Emanuel, & Updegraff, 2012).

Rumination may lead to negative mood after stressful life events because it is associated with reduced capacity to disengage attention from negative emotional information (Joormann, 2006). In addition, rumination is associated with difficulties in generating good solutions to problems (Donaldson & Lam, 2004; Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995; Ward, Lyubomirsky, Sousa, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003; Watkins & Moulds, 2005; Watkins & Baracaia, 2002) and decreased willingness to engage in mood-lifting activities (Lyubomirsky, Kasri, Chang, & Chung, 2006; Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1993). Thus, rumination after stressful events could undermine individuals’ attempts to solve their problems or to engage in other more positive coping activities, leading to depressive and anxiety symptoms.

The role of rumination as a mechanism linking self-reported life events to increases in internalizing symptoms did not vary by gender. There are well-established gender differences in trait rumination and in the prevalence of depression and anxiety symptomatology beginning in adolescence and continuing throughout adulthood (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2001; Nolen-Hoeksema & Girgus, 1994; Twenge & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002). Despite these gender differences in average levels of rumination and symptoms of depression and anxiety, however, there is little reason to expect gender differences in the relationship between rumination and psychopathology. Indeed, previous research suggests a lack of gender difference in this relationship in both adolescents and adults (Hilt, McLaughlin, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010; Nolen-Hoeksema & Aldao, 2011), and such a difference was not predicted theoretically (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2001; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1999).

Our results also show no gender differences in the relationship between stressful life events and rumination. Although females and males may be equally likely to engage in rumination following stressful life events, females may be more likely than males to experience certain types of stressors that lead to rumination, namely uncontrollable interpersonal stressors (e.g., sexual abuse, harassment at work; Nolen-Hoeksema, 1994). We found no gender difference in reports of stressful life events in our adolescent sample, but did find that women reported a significantly greater number of stressful life events than men in the adult sample (see also Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1999).

The findings of this study point to several promising areas of future inquiry. Although rumination is typically conceptualized as a stable trait, our findings suggest that perceived changes in the social environment can increase engagement in rumination. Given the potent role that rumination plays in the etiology of major depression and anxiety pathology, identifying factors associated with the development of a ruminative response style is critical to facilitate the targeting of interventions toward adolescents and adults at high risk for the development of psychopathology.

Some studies have found that rumination interacts with stressful life events to predict depression, such that individuals high in rumination are more likely to experience depression following stressors than those who do not ruminate (e.g., Driscoll, Lopez, & Kistner, 2009; Robinson & Alloy, 2003). Our findings suggest that the relationship between stressful life events and depression might be more complicated. Specifically, exposure to stressful life events might lead to increased engagement in rumination, regardless of one’s level of trait rumination at the time of the stressor, which in turn increases risk for internalizing psychopathology. Although risk for depression is likely to be particularly heightened among those already prone to ruminate, our findings suggest that increases in rumination are not confined to those with high trait rumination. In sensitivity analyses conducted in both of our samples, we found that increases in rumination following stressful life events did not occur exclusively among those with high levels of rumination at baseline. These findings are important because they suggest that engagement in rumination might represent a global response to experiences of stress that underlies the strong relationship between stressful life events and internalizing psychopathology. This possibility warrants further investigation in future research.

An alternative interpretation of our findings is that the negative affect generated by exposure to stressful life events, rather than the experiences themselves, is the factor that results in heightened levels of rumination following stressors. Our finding that perceived stressful life events are associated prospectively with rumination even after controlling for internalizing symptoms assessed at the same time point as the perceived life events argues against this interpretation. Nevertheless, inclusion of measures of perceived distress following stressors will allow these relationships to be disentangled to a greater degree than was possible in the current studies.

Identifying mechanisms linking stress and psychopathology is critical to develop interventions aimed at preventing the onset of stress-related mental disorders. Our findings suggest that rumination is a promising target for such interventions in both adolescents and adults who have experienced recent stressors. One example of a relevant intervention is rumination-focused cognitive–behavioral therapy (RFCBT; Watkins et al., 2007). The goal of RFCBT is to help individuals identify their ruminative thoughts and help them to shift into more effective thinking styles. Watkins and colleagues (2011) found that RFCBT was a beneficial treatment for persistent depression in adults compared with treatment as usual. Although RFCBT has also been examined as a treatment for adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder in a small pilot study (Sezibera, Van Broeck, & Philippot, 2009), the effectiveness of rumination-focused interventions for the treatment of adolescent disorders remains unknown. More critically, the extent to which the techniques used in RFCBT could be applied in preventive interventions aimed at reducing risk for anxiety and depression following social environmental stressors has yet to be examined empirically. This remains an important goal for future research. Mindfulness mediation and other interventions focusing on emotional experience have also been shown to reduce engagement in rumination among previously depressed individuals (Jain et al., 2007; Kingston, Dooley, Bates, Lawlor, & Malone, 2007; Ramel, Goldin, Carmona, & McQuaid, 2004). Mindfulness is therefore another promising technique that might be useful in interventions aimed at preventing the onset of internalizing problems among individuals exposed to stressful life events.

Study findings should be interpreted in light of several key limitations. First, our measures of stress in both the adult and adolescent samples relied on stressful life events questionnaires. Questionnaire checklists are limited both by recall failure and bias as well as misclassification problems (Dohrenwend, 2006; Raphael, Cloitre, & Dohrenwend, 1991). Interview methods have been developed that largely overcome these methodological problems with checklists (Hammen, 2008). Given their time intensive nature, however, we were not able to use this approach in the current study. The primary concern about use of a life events checklist is that individuals vary widely in the degree to which they experience negative affect in response to stressors, and those who are experiencing low mood or are already engaging in high levels of rumination might be most likely to perceive and report stressful life events. This concern is partially mitigated by the longitudinal design of our studies; rumination was measured between 4 and 12 months after the assessment of stressful life events. This time lag makes it less likely that the relationship between rumination and reports of stressful life events is explained entirely by greater propensity for perceiving or reporting stressors among those with high levels of rumination. Moreover, the nature of our statistical models takes into account, at least in part, the influence that both rumination and internalizing symptoms have on the perceptions/reports of stress because Time 1 rumination was a covariate in all longitudinal models and the relationship between perceived life events and rumination remained significant after controlling for Time 1 internalizing symptoms. Finally, the relationship between perceived stressful life events and rumination remained significant when we removed several events from each scale (e.g., items involving interpersonal conflicts) to ensure that only relatively objective events (e.g., divorce, illness of a family member) were retained. Nevertheless, the possibility that personality traits or other factors that are stable over time across individuals influenced reports of both stressful life events and rumination remains a possibility. Replication of the relationship between stress and rumination in studies that use more rigorous interview-based measures of stress exposure is therefore required.

Second, our analysis focused on self-reported symptoms of depression and anxiety. Although the association between rumination and onset of clinician-identified depressive episodes is well established (Abela & Hankin, 2011; Just & Alloy, 1997; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Robinson & Alloy, 2003), the role of rumination as a risk factor for the later onset of anxiety disorders requires further empirical examination. As such, future studies would benefit from the use of a clinical interview to establish the relationship between rumination and the onset of anxiety disorders. Third, we used a domain representative parceling approach to construct our latent variables. The issue of whether or not to use parcels to model latent variables in structural equation models is a controversial and hotly debated topic, with most studies noting both advantages and limitations of the approach (Bagozzi & Edwards, 1998; Bandalos, 2002; Coffman & MacCallum, 2005; Kishton & Widaman, 1994; Little et al., 2002). Drawbacks of using parcels include the possibility of model misspecification if constructs are multidimensional and items load onto an additional latent factor that is not included in the model and reduced interpretability of scales that have established norms (Little et al., 2002). As such, we empirically examined different methods for constructing the latent variables used in this study and found that the domain representative parceling approach provided the best fit to our data. However, because the constructs examined in the current study are multidimensional, it is possible that the lower order factors would have behaved differently than the higher order constructs used in our models. Although we did not have specific hypotheses about these lower order factors, examining the role of rumination as a mechanism linking stressful life events to specific types of anxiety and depressive symptoms is an important direction for future research.

Fourth, although the longitudinal design allowed us to establish the temporal ordering of stressful life events, rumination, and changes in internalizing symptoms, the relationships between stress and internalizing psychopathology and between internalizing psychopathology and rumination are almost certainly reciprocal. Consistent evidence suggests that individuals with depression and anxiety contribute to the generation of stress in their lives (Hammen, 1991; Rudolph et al., 2000). In addition, although rumination clearly predicts increases in symptoms of depression and anxiety, experience sampling evidence suggests that negative affect is also associated with later increases in rumination (Moberly & Watkins, 2008). A final limitation of the current study is the use of only two assessment time points in the adult sample, making our mediation analysis of this population more limited. A preferable approach is to use multiwave data to establish that the exposure predicts changes in the mediator that precede changes in the outcome (Cole & Maxwell, 2003; Maxwell & Cole, 2007), as we were able to do in the adolescent sample. To more rigorously test the conceptual model in adults, a prospective study with three waves of data is required.

Rumination is among the most robust vulnerability factors for the development of internalizing psychopathology (Aldao et al., 2010). Although extensive research has examined the consequences of engagement in rumination, few studies have sought to identify vulnerability factors for rumination itself. Our findings suggest that self-reported stressful life events are associated with subsequent increases in ruminative responses to distress among both adolescents and adults. Moreover, results indicate that rumination is an important psychological mechanism linking perceived stress exposure to symptoms of depression and anxiety. These findings have important implications for guiding the development of prevention programs aimed at reducing vulnerability to internalizing problems and stress-related psychiatric morbidity.

Contributor Information

Louisa C. Michl, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School

Katie A. McLaughlin, Department of Pediatrics & Psychiatry, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School

Kathrine Shepherd, Department of Psychology, Kent State University.

Susan Nolen-Hoeksema, Department of Psychology, Yale University.

References

- Abela JR, Brozina K, Haigh EP. An examination of the response styles theory of depression in third- and seventh-grade children: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:515–527. doi: 10.1023/A:1019873015594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JR, Hankin BL. Rumination as a vulnerability factor to depression during transition from early to middle adolescence: A multiwave longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:259–271. doi: 10.1037/a0022796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi RP, Edwards JR. A general approach for representing constructs in organizational research. Organizational Research Methods. 1998;1:45–87. doi: 10.1177/109442819800100104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandalos DL. The effects of item parceling on goodness-of-fit and parameter estimate bias in structural equation modeling. Educational Psychology Papers and Publications. 2002 Paper 65. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/edpsychpapers/65/

- Baumeister RF, Gailliot M, DeWall CN, Oaten M. Increase regulatory success, and how depletion moderates the effects of traits on behavior. Journal of Personality. 2006;74:1773–1801. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauregard M, Lévesque J, Bourgouin P. Neural correlates of conscious self-regulation of emotion. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:RC165. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-j0001.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Beck RW. Screening depressed patients in family practice: A rapid technique. Postgraduate Medicine. 1972;52:81–85. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1972.11713319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the revised Beck Anxiety Inventory. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blagden JC, Craske MG. Effects of active and passive rumination and distraction: A pilot replication with anxious mood. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1996;10:243–252. doi: 10.1016/0887-6185(96)00009-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick MM, Cohen JD, Carter CS. Conflict monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: An update. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2004;8:539–546. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW. Life events and affective disorder: Replications and limitations. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1993;55:248–259. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199305000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler ID, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in response to depressed mood in a college sample. Sex Roles. 1994;30:331–346. doi: 10.1007/BF01420597. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. Attention and self-regulation: A control-theory approach to human behavior. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1981. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla JA, Reilly LC, Dickson KS, Emanuel AS, Updegraff JA. Dispositional mindfulness moderates the effects of stress among adolescents: Rumination as a mediator. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41:760–770. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.698724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coddington DR. The significance of life events as etiologic factors in the diseases of children: A study of normal population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1972;16:205–213. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(72)90045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffman DL, MacCallum RC. Using parcels to convert path analysis models into latent variable models. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2005;40:235–259. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4002_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L, Burt C, Bjork J. Life stress and adjustment: Effects of life events experienced by young adolescents and their parents. Developmental Psychology. 1987;23:583–592. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.23.4.583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE. Stress and life events during childhood and adolescence. Clinical Psychology Review. 1987;7:275–302. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(87)90037-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Grant KE. Stress and adolescent depressive symptoms: Underlying mechanisms and processes; Paper presented at the biannual meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; New Orleans, LA. 1993. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Malcarne VL, Fondacaro KM. Coping with stressful life events in older children and young adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:405–411. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.3.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connecticut Department of Education. Strategic school profile 2005–2006: New Britain Public Schools. Hartford, CT: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Craighead WE, Smucker MR, Craighead LW, Ilardi SS. Factor analysis of the Children’s Depression Inventory in a community sample. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP. Inventorying stressful life events as risk factors for psychopathology: Toward resolution of the problems of intracategory variability. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:477–495. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.3.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson C, Lam D. Rumination, mood and social problem solving in major depression. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:1309–1318. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704001904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll KA, Lopez CM, Kistner JA. A diathesis-stress test of response styles in children. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2009;28:1050–1070. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2009.28.8.1050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD, Williams KD. Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science. 2003 Oct 10;302:290–292. doi: 10.1126/science.1089134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fresco DM, Frankel AN, Mennin DS, Turk CL, Heimberg RG. Distinct and overlapping features of rumination and worry: The relationship of cognitive production to negative affective states. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2002;26:179–188. doi: 10.1023/A:1014517718949. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Thurm AE, McMahon SD. Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Measurement issues and prospective effects. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:412–425. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:555–561. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Stress exposure and stress generation in adolescent depression. In: Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt LM, editors. Handbook of depression in adolescents. New York, NY: Routledge; 2008. pp. 305–334. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Goodman-Brown T. Self-schemas and vulnerability to specific life stress in children at risk for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1990;14:215–227. doi: 10.1007/BF01176210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington JA, Blankenship V. Ruminative thoughts and their relation to depression and anxiety. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2002;32:465–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00225.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J. How does stigma “get under the skin”? Psychological Science. 2009;20:1282–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilt LM, McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Examination of the response style theory in a community sample of young adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:545–556. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9384-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inzlicht M, McKay L, Aronson J. Stigma as ego depletion: How being the target of prejudice affects self-control. Psychological Science. 2006;17:262–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Shapiro SL, Swanick S, Roesch SC, Mills PJ, Bell I, Schwartz GE. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training: Effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination, and distraction. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;33:11–21. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3301_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, Raye CL, Mitchell KJ, Touryan SR, Greene EJ, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Dissociating medial frontal and posterior cingulate activity during self-reflection. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2006;1:56–64. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsl004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J. Differential effects of rumination and dysphoria on the inhibition of irrelevant emotional material: Evidence from a negative priming task. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2006;30:149–160. doi: 10.1007/s10608-006-9035-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Just N, Alloy L. The response styles theory of depression: Tests and an extension of the theory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:221–229. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.106.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Hettema JM, Butera F, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Life event dimensions of loss, humiliation, entrapment, and danger in the prediction of onset of major depression and generalized anxiety. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:789–796. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:837–848. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston T, Dooley B, Bates A, Lawlor E, Malone K. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for residual depressive symptoms. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 2007;80:193–203. doi: 10.1348/147608306X116016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishton JM, Widaman KF. Unidimensional versus domain representative parceling of questionnaire items: An empirical example. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1994;54:757–765. doi: 10.1177/0013164494054003022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory manual. North Tonawanda NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lane RD, Reiman EM, Axelrod B, Yun L-S, Holmes A, Schwartz GE. Neural correlates of levels of emotional awareness: Evidence of an interaction between emotion and attention in the anterior cingulate cortex. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1998;10:525–535. doi: 10.1162/089892998562924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To parcel or not to parcel: Examining the question, weighing the evidence. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:151–173. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Kasri F, Chang O, Chung I. Ruminative response styles and delay of seeking diagnosis for breast cancer symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2006;25:276–304. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2006.25.3.276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Self-perpetuating properties of dysphoric rumination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:339–349. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]