Abstract

This study examined the relationship between the characteristics of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) and the severity of consequent posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, suicidal ideation, and substance use in a sample of 83 female adolescents aged 13-18 years seeking treatment for PTSD. Nearly two-thirds of the sample (60.7%, n = 51) reported the perpetrator of the CSA was a relative. A large portion (40.5%, n = 34) of the sample reported being victimized once, while almost a quarter of the sample reported chronic victimization (23.8%, n = 20). PTSD and depression scores were in the clinical range, whereas reported levels of suicidal ideation and substance use were low. The frequency of victimizations was associated with suicidal ideation. Contrary to expectation, CSA characteristics including trauma type, perpetrator relationship, and duration of abuse were unrelated to PTSD severity, depressive symptoms, or substance abuse.

Keywords: childhood sexual abuse, posttraumatic stress disorder, adolescent mental health

Child sexual abuse (CSA) is defined as any forced or coerced sexual activity with a minor including noncontact abuse, sexual molestation, and rape (American Psychological Association, 2012). CSA is a serious public health problem that affects a substantial number of children in the United States each year. In the most comprehensive study of child abuse to date, the Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect, it was estimated that 135,300 children are sexually abused each year (National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect, 2010). Because many incidences of CSA are not reported, the actual incidence is thought to be significantly larger than this estimated figure (Watkins & Bentovim, 1992).

The possible negative consequences of CSA are numerous. CSA has been identified as a risk factor for several mental health problems during adolescence including depression (e.g., Buzi, 2007), suicidality (e.g., Brent et al., 2002), low self-esteem (e.g., Cecil & Matson, 2005), and risky behavior such as substance use (e.g., Shin, Hong, & Hazen, 2010). One of the disorders most frequently associated with CSA is posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Deblinger, Hefler, & Clark, 1997; McCutcheon et al., 2010). The rate of PTSD among adolescents who were sexually abused as children has been estimated at 38.5% in nonclinical samples (Perkonigg, Kessler, Storz, & Wittchen, 2000) and as high as 88% in clinical samples (Carey, Walker, Rossouw, Seedat, & Stein, 2008).

Many studies attempting to identify factors that influence the impact of CSA on future mental health outcomes have focused on abuse characteristics. One abuse characteristic that has been linked with subsequent PTSD is the severity of abuse including the type, duration, and frequency of CSA. Among adults, more severe types of CSA (e.g., rape) have been associated with a higher risk for PTSD, compared to less severe types (e.g., molestation; Briggs & Joyce, 1997; Feerick & Snow, 2005). One study found CSA severity accounted for 33% of the variance in PTSD symptoms in treatment-seeking adults (Rodriguez et al., 1996). The relationship between the perpetrator and the victim has also been identified as an important predictor of the occurrence and severity of PTSD in adult survivors of CSA. Specifically, PTSD symptoms were significantly higher among CSA survivors who were abused by a family member compared to those who were abused by a stranger (Lev-Wiesel et al., 2005).

Research with adult survivors of CSA has provided insight into the relationship between characteristics of CSA and consequent PTSD. However, findings regarding adult experiences of CSA and resultant PTSD may not generalize to adolescents for several reasons. One reason is that CSA is a more recent trauma for adolescents than for adults. Not only has length of time since a trauma been shown to significantly predict PTSD severity (see Foy, Madvig, Pynoos, & Camilleri, 1996) but there is evidence that the factors that predict PTSD soon after a trauma are not the same as those that predict PTSD later on (Adams & Boscarino, 2006). Second, adolescents express PTSD and related conditions differently than do adults. For example, in a survey study of trauma-exposed youth, Ayer et al. (2011) found that numbing symptoms were not related to PTSD severity in adolescents the way they are in adults. Research has also shown that CSA survivors are more vulnerable to becoming depressed and suicidal during adolescence relative to adulthood (Brown, Cohen, Johnson, & Smailes, 1999).

Research on the relationship between CSA characteristics and PTSD among adolescents has yielded less consistent results than in studies with adults. In adolescent CSA survivors, some studies have found that the type of victim-perpetrator relationship is associated with PTSD (e.g., Lawyer, Ruggiero, Resnick, Kilpatrick, & Saunders, 2006) but other studies have not (e.g., Wolfe, Sas, & Wekerle, 1994). Similarly, some studies have found that duration and type of abuse were associated with psychopathology in children and adolescents (e.g., Lucenko, Gold, & Cott, 2000; Wolfe et al., 1994) while other studies have not (Mennen & Meadow, 1995). One explanation for these mixed findings is that previous studies examining PTSD among adolescent CSA victims have focused on diagnosis of PTSD rather than upon the severity of PTSD symptoms. This focus shift may be responsible for the reduced probability of finding a significant effect between characteristics of CSA and PTSD.

To better understand the impact of CSA, it is important to identify the factors that increase risk for PTSD and related psychopathology in adolescent survivors of CSA. However, studies to date have either focused on adult samples or yielded mixed results. The purpose of the current study was to examine characteristics of CSA and the severity of PTSD and related problems among adolescents seeking treatment for PTSD. We hypothesized that a closer perpetrator-victim relationship and a greater frequency of victimizations would each predict more severe PTSD depressive symptoms, suicidality, and substance abuse. In addition, we explored the relationship between CSA type (e.g., rape) and PTSD severity, depressive symptoms, suicidality, and substance abuse.

Method

Participants

The participants were 83 female adolescents aged 13 – 18 years (M = 15.42; SD = 1.49) seeking treatment for PTSD at Women Organized Against Rape (WOAR), a community mental health clinic in Philadelphia that provides counseling to survivors of rape and childhood sexual abuse. The majority of the sample was African American (56.6%), 24.1% was bi-racial, 14.5% was Caucasian, 3.6% was of Spanish origin, and 1.2% was Asian/Pacific Islander.

Adolescents with a primary diagnosis chronic or subthreshold PTSD (≥1 re-experiencing symptom, ≥ 2 avoidance symptoms, and ≥ 2 hyperarousal symptoms) resulting from rape or attempted rape by same-age peers, or sexual abuse (by a perpetrator five or more years older were eligible to participate. Adolescents with primary diagnoses other than PTSD such as conduct disorder, alcohol or substance dependence, or suicidal ideation with intent, were excluded.

Measures

Schedule of Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Epidemiological Version (K-SADS-E; Orvaschel, 1995)

The K-SADS is a semi-structured clinician-administered interview of DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric disorders that incorporates both child and parent reports. The K-SADS had excellent reliability and validity (Orvaschel et al., 1982).

Child PTSD Symptom Scale (CPSS; Foa, Johnson, Feeny, & Treadwell, 2001)

The CPSS is a 24-item clinician-administered interview that maps on DSM-IV criteria, yielding a PTSD total score as well as scores on the re-experiencing, avoidance and hyperarousal subscales. Items are rated on a scale from 0 to 3; with total score ranging from 0 to 51. During the original development of the scale, internal consistency ranged from .70 - .89 for the total and subscales symptom scores (Foa et al., 2001). The CPSS has good test-retest reliability (.84 for the total score, .85 for reexperiencing, .63 for avoidance and .76 for hyperarousal), good convergent validity, and good discriminant validity (Foa, et al., 2001). Functional analysis indicated that a linear combination of the three subscales significantly discriminated between diagnostic groups (Wilks lambda = .33, X2 (3) = 79.1, p <.0001; Foa et al., 2001).

Trauma History Interview (THI)

The THI is a revised version of the Standardized Assault Interview (SAI; Rothbaum, Foa, Riggs, Murdock, & Walsh, 1992) that can be used to help establish PTSD diagnosis and identify a target trauma. The SAI has a demonstrated interrater reliability of .90 (Rothbaum et al., 1992).

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1961)

The BDI is a self-report measure of depression that is widely used in a variety of populations, including trauma victims (Foa et al., 1991). The scale has 21 items, each consisting of four self-statements. The statements are assigned values of 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating more severe symptomatology. Total scores range from 0-63. Individuals are instructed to endorse those statements which have been true for them during the past week (Radnitz, et al., 1997). Split half-reliability is .93, and correlations with clinician ratings of depression range from .62 to .65 (Beck et al., 1961). It has been found sensitive to treatment effects in numerous treatment outcome studies (e.g., Foa et al., 1992).

Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Junior (SIQ-JR; Reynolds, 1987)

The SIQ-JR is a 15-item instrument used to identify and assess suicidal ideation in adolescents. Items are scored on a 7-point scale, ranging from 0-6, with 6 being the most severe. A cutoff score of 21 has been identified as indicating a clinically significant level of suicidal ideation (Reynolds, 1988). The SIQ-JR has been shown to be a valid and reliable measure of suicidality in children and young adolescents, from a variety of cultural backgrounds (Reynolds & Mazza, 1999; Keane, Dick, Bechtold, & Manson, 1996; Ang & Ooi, 2004).

Personal Experience Screening Questionnaire (PESQ; Winters, 1991)

The PESQ is a 40-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess lifetime and current alcohol and drug use among 12-18 year olds. Across several empirical studies, the PESQ has demonstrated internal consistency estimates of 0.90 or higher (see Shields et al., 2008).

Procedure

The current study was part of a larger randomized controlled trial of Prolonged Exposure for adolescents with PTSD that enrolled study participants from 2007-2012 and completed all follow-up assessment in January of 2013. Participants were recruited from the following sources: 1) direct referrals to WOAR; 2) referrals to WOAR from their outreach efforts within the Philadelphia School District; 3) referrals from mental health providers and pediatricians or other physicians in the Philadelphia area; 4) referrals from the adolescent sexual abuse evaluation unit of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP); and 5) referrals to WOAR from local community organizations. Potential participants completed an intake assessment at WOAR that included assessment of trauma history, social and family functioning, and drug and alcohol use. Symptoms of PTSD were assessed using the CPSS. Adolescents who met study criteria based on this initial assessment were informed about the opportunity to participate in the study and were invited to complete a baseline evaluation to determine study eligibility.

Baseline evaluations were conducted by independent evaluators (IEs), who were doctoral-level clinicians from the Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety at the University of Pennsylvania. During the evaluation, the IE interviewed the adolescent and the guardian separately to assess current and lifetime disorders including PTSD, using the K-SADS. Baseline evaluations consisted of a diagnostic interview (using the K-SADS-E) and self-report measures of PTSD and related problems. The CPSS was then used to determine PTSD severity. The IE also reviewed the Trauma History Interview with the participant and completed information that was not obtained in the WOAR intake. After obtaining informed consent (or assent for adolescents ≤ age 17), eligible participants were asked to complete the self-report questionnaires described above. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania.

Data Analytic Approach

Participants' descriptions of the type of trauma were recoded into three categories: rape was defined as a single incidence of sexual trauma in which vaginal or anal penetration occurred, sexual assault was defined as a single incidence of sexual trauma that did not include vaginal or anal penetration, and sexual abuse was defined as rape or sexual assault that occurred more than one time.

Previous studies have not used a uniform system for categorizing perpetrator relationship to the survivor. Examples include categorizing the perpetrator as either family member or stranger (e.g., Lev-Wiesel, Amir, & Besser, 2005) and labeling the perpetrator as a parent, family member, family friend, stranger, or “other” (Feerick & Snow, 2005). For the present study, participants' relationship to their perpetrator was categorized into three groups. Strangers, acquaintances, and friends were categorized as non-relatives. Step-parents and step-siblings as well as mother's romantic partners and god-parents were categorized as non-blood relatives. All immediate family members, including grandparents, were categorized as blood-relatives.

Four outliers were identified on the CPSS-SR; three in the upper extreme and one in the lower extreme. One upper extreme outlier was identified in the SIQ-JR. Data was recoded using the Winzor method.

ANOVAs were conducted to examine the relationships between trauma characteristics and severity of PTSD, depression, suicidality, and substance use. To correct for multiple comparisons, the Holm procedure was applied, which involves setting different alpha levels for rejecting individual hypotheses (Holm, 1979). The p-values were ordered from smallest to largest, and the smallest p -value was subjected to the most conservative alpha level (i.e., α = .05/3 for this study; equivalent to the Bonferroni correction). Subsequent p-values were then compared to sequentially-increasing alpha levels (i.e., α = .05/2 for the second hypothesis, α = .05/1 for the third hypothesis), thus gaining statistical power at each step by sequentially increasing the criterion for statistical significance (see Olejnik, Li, Supattathum, & Huberty, 1997 for a review of this procedure).

Results

Trauma Characteristics

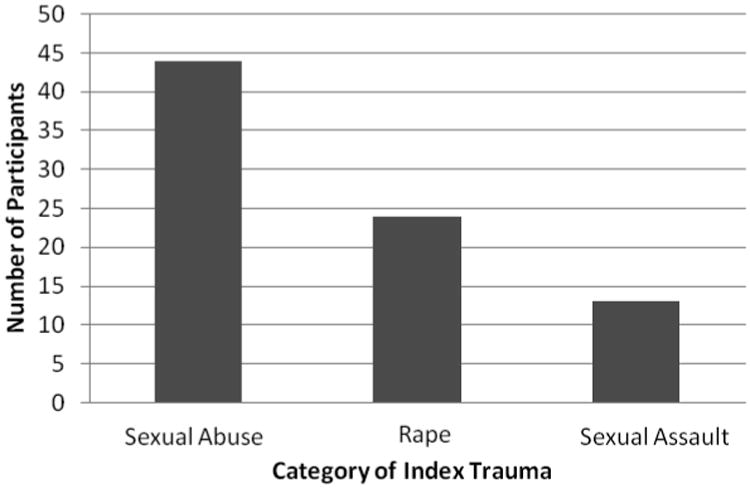

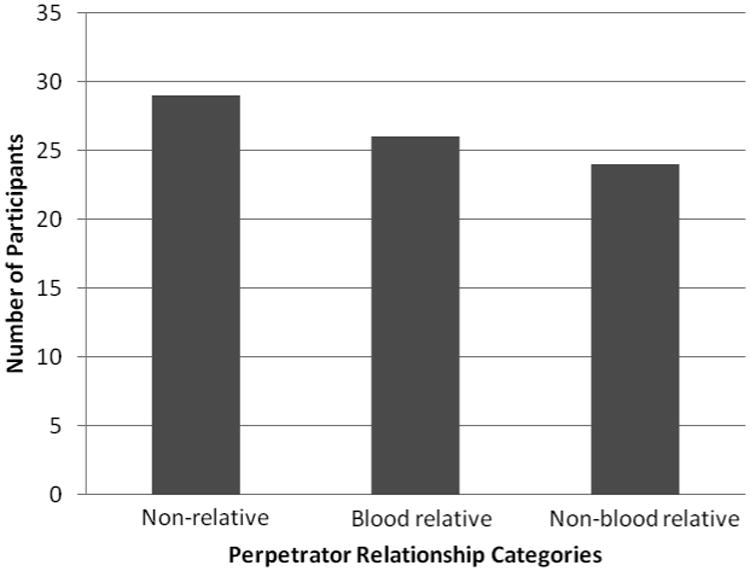

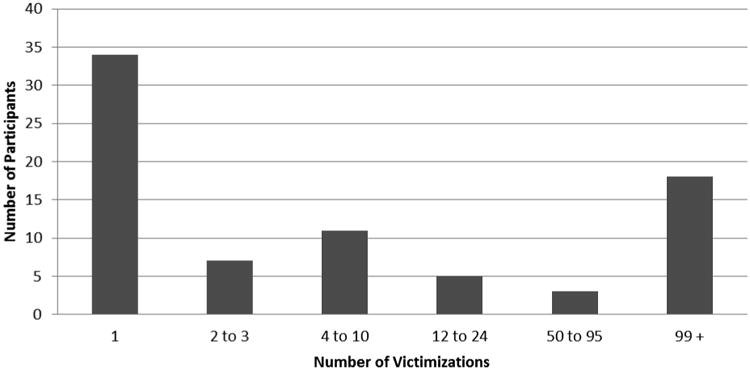

The index traumas reported were sexual abuse (52.4%, n = 44), rape (28.6%, n = 24), and sexual assault (15.5%, n = 13; see Figure 1). The perpetrator of the abuse was identified as a non-relative (i.e., stranger, acquaintance; 34.5%, n = 29), a blood-relative (i.e., parent, sibling; 32.1%, n = 27), and non-blood-relative (i.e., step-parent; 28.6%, n = 24; see Figure 2). A large portion of the sample reported being victimized once (40.5%, n = 34) while almost a quarter of the sample reported chronic victimization that was difficult to quantify; this response was coded as >99 victimizations (23.8%, n = 20). Thus, the mean number of victimizations, 29.78 (41.99), does not represent the bimodal distribution of this variable (see Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Number of participants reporting each category of index trauma.

Figure 2.

Number of participants reporting each category of perpetrator relationship.

Figure 3.

Number of participants reporting incidence of victimizations.

Psychopathology

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for the sample on each of the outcome measures. Mean PTSD scores were above the clinical cut-off of 11 (Foa et al., 2001) on the total CPSS score, M = 28.51 (7.37), and each of the CPSS subscales: Reexperiencing M = 7.57 (2.93); Avoidance M = 10.90 (3.92); and Arousal M = 10.03 (3.00). The mean depression score on the BDI fell in the moderate range, M = 22.55(9.78), and the mean suicidality score on the SIQ-JR score was 21.58 (23.34), which falls below the clinical cut-off of 31 (Reynolds, 1988). The mean substance use, measured by the PESQ Problem Severity Scale was within one standard deviation of the mean for a non-clinical sample (Winters, 1992), M = 23.39(6.89).

Table 1. Mean Scores on Main Outcome Measures.

| Measure | n | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| CPSS | 83 | 28.51 (7.37) |

| Reexperiencing | 83 | 7.57 (2.93) |

| Avoidance | 83 | 10.90 (3.92) |

| Arousal | 83 | 10.03 (3.00) |

| BDI | 71 a | 22.55 (9.78) |

| SIQ-JR | 43 b | 21.58 (23.34) |

| PESQ | 83 | 23.39 (6.89) |

Note. CPSS = Child PTSD Symptom Scale; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; SIQ-JR = Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Junior; PESQ = Personal Experience Questionnaire.

=decreased n due to missing data from 13 subjects

=decreased n due to missing data from 40 subjects

Trauma Characteristics and Psychopathology

One-way ANOVAs were used to test for differences in PTSD severity based on type of index trauma, perpetrator identity, and number of victimizations. PTSD severity did not differ significantly across trauma type (F (3, 78) = .827, p = .483), perpetrator identity (F (3, 78) = .428, p = .734), or number of victimizations (F (15, 77) = .702, p = .773).

One-way ANOVAs were used to test for differences in depression severity based on type of index trauma, perpetrator identity, and number of victimizations. Depression severity did not differ significantly across trauma type, (F (3, 70) = .593, p = .621), perpetrator identity (F (3, 70) = .528, p = .665), or number of victimizations (F (15, 68) = 1.338), p = .214).

One-way ANOVAs were used to test for differences in suicidality based on type of index trauma, perpetrator identity, and number of victimizations. Suicidality did not differ significantly across trauma type, (F (3, 42) = 1.099, p = .361), or perpetrator identity (F (3, 42) = .149, p = .930). Suicidality did differ significantly based on number of victimizations (F (12, 41) = 3.399), p = .003).

Discussion

This study examined trauma characteristics and symptoms of PTSD and associated psychopathology in a sample of treatment-seeking female adolescents with a history of childhood sexual abuse. The mostly commonly reported trauma in this sample was sexual abuse, followed by rape, then sexual assault. An equal number of participants reported the perpetrator of the CSA was a blood-relative, a non-blood relative, and a non-relative. Thus, two-thirds of the sample reported CSA perpetrated by a relative. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that CSA is more likely to be perpetrated by a family member than a non-family member (e.g., Gold, Hughes, & Swingle, 1996; Crisma, Bascelli, Paci, & Romito, 2004). The distribution of CSA frequency was bimodal; many participants (approximately 2 in 5) reported only one incidence of CSA, while other participants (approximately 1 in 5) reported chronic CSA occurring so frequently and/or over an extended period of time (i.e., several years) that the response was coded at “>99 incidents”.

Participants in this study reported minimal suicidal ideation, which is consistent with some previous research (Brand, King, Olson, Ghaziuddin, & Naylor, 1996). We found that suicidality was significantly associated with the frequency of victimizations suggesting that adolescent survivors of CSA who have suffered from chronic abuse are at particularly high risk for suicide. This is consistent with a recent study by Soylu and Alpaslan (2013), who found that adolescents exposed to continuous CSA reported greater suicidal ideation than those exposed to a single CSA incident. In contrast to the current study, Soylu and Alpaslan also found that a closer relationship to the perpetrator and the type of CSA predicted suicidal ideation. The results of the current study underscore the importance of screening adolescent CSA survivors for suicidal ideation, and provide further support for the hypothesis that the frequency of victimizations is an important indicator to help identify adolescent at a higher risk for suicide.

Rates of substance use fell within the non-clinical range. Although substance dependence was an exclusion criterion in this study, the low level of substance use is still surprising given that a history of CSA and symptoms of PTSD have each been identified as risk factors for problematic substance use in adolescence (Giaconia, Reinherz, Paradis, Stashwick, & 2003). A study conducted by Kingston and Raghavan (2009) found that CSA was not related to an earlier age of substance use initiation. While participants in our study reported low levels of substance use, it is possible their use may increase over time.

Contrary to our hypotheses, none of the CSA characteristics examined (type of CSA, perpetrator of the abuse, or frequency of abuse) were significantly related to the severity of PTSD, depression or substance use. These null findings were unexpected given that research with adult CSA survivors has found that these characteristics are predictors of the development and severity of PTSD. Although some studies with adolescents have found significant relationships between CSA characteristics and PTSD (e.g., Lawyer et al., 2006), these studies have relied on non-clinical samples of CSA survivors. Studies with treatment-seeking adolescents have not found significant relationships between symptoms of PTSD and specific CSA characteristics including perpetrator identity, type of abuse, and duration of abuse (Mennen & Meadow, 1995; Wolfe et al., 1994). Sample characteristics may explain these discrepant findings. In the current study, all participants reported moderate to high PTSD severity. Therefore, there was a restricted range of scores on the criterion variable. This may explain why studies of non-clinical samples have identified significant relationships between CSA characteristics and PTSD while the present study did not.

In a prospective study of sexually abused children, Tebbutt (1996) found that continued contact with the abuser was an important predictor of functioning at a 5-year follow-up. Also, Wolfe, et al. (1994) found that when the perpetrator was not a father figure, the use of force predicted PTSD symptom severity. Neither continued contact with the perpetrator nor use of force was examined in this study. Future studies should examine these variables among on treatment seekers.

A strength of this study is the ethnically diverse clinical sample; more than half of the sample identified as African American and another quarter as bi-racial. Thus, the participants in the current study were representative of the urban population from which they were drawn. In contrast, a majority of the participants in epidemiological studies of adolescent CSA survivors were Caucasian (e.g., Lawyer et al., 2006; Danielson et al., 2010). Although CSA survivors are disproportionally female, a significant minority of CSA victims is male (Lawyer et al., 2006). It is important to note that this study recruited only female adolescents and that the results may not generalize to male survivors of CSA.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institute of Health, Grant 5-R01-MH-074505-04, PI: Edna Foa.

References

- American Psychological Association. Understanding Child Sexual Abuse: Education, Prevention, and Recovery. 2012 [Brochure]. Retrieved June 10, 2012 from http://www.apa.org/pubs/info/brochures/sex-abuse.aspx.

- Adams RE, Bascarino JA. Predictors of PTSD and Delayed PTSD after Disaster. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194(7):485–493. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000228503.95503.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang RP, Ooi YP. Impact of gender and parents' marital status on adolescents' suicidal ideation. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2004;50(4):351–360. doi: 10.1177/0020764004050335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayer L, Danielson CK, Amstadter AB, Ruggiero K, Saunders B, Kilpatrick D. Latent classes of adolescent posttraumatic stress disorder predict functioning and disorder after 1 year. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(4):364–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelsohn M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler LE, Williams RE, Zetzer HA. Efficacy of treatment for victims of child sexual abuse. The Future of Children. 1994;4(2):156–175. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1602529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand EF, King CA, Olson E, Ghaziuddin N, Naylor M. Depressed Adolescents with a history of sexual abuse: diagnostic comorbidity and suicidality. Journal of the American Academy of child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35(1):743–751. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199601000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Oquendo M, Birmaher B, Greenhill L, Kolko D, Stanley B, Mann JJ. Familial pathways to early-onset suicide attempt: risk for suicidal behavior in offspring of mood-disordered suicide attempters. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(9):801–807. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.9.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs L, Joyce PR. What determines post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology for survivors of childhood sexual abuse? Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997;21(6):575–582. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Cohen P, Johnson JG, Smailes EM. Childhood abuse and neglect: Specificity of effects on adolescent and young adult depression and suicidality. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(12):1490–1496. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199912000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzi RS, Weinman ML, Smith P. The relationship between adolescent depression and a history of sexual abuse. Adolescence. 2007;42(168):679–688. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/621993384?accountid=14707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey PD, Walker JL, Rossouw W, Seedat S, Stein DJ. Risk indicators and Psychopathology in traumatised children and adolescents with a history of sexual abuse. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;17:93–98. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0641-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecil H, Matson SC. Differences in psychological health and family dysfunction by sexual victimization type in a clinical sample of African American adolescent women. Journal of Sex Research. 2005;42(3):203–214. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0641-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisma M, Bascelli E, Paci D, Romito P. Adolescents who experienced sexual abuse: Fears Needs and impediments to disclosure. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28(10):1035–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigneault I, Tourigny M, Hebert M. Self-attributions of blame in sexually abused adolescents: A meditational model. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19(1):153–157. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson CK, Macdonald A, Amstadter AB, Hanson R, de Arellano MA, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG. Risky behaviors and depression in conjunction with — or in the absence of—lifetime history of PTSD among sexually abused adolescents. Child Maltreatment. 2010;15(1):101–107. doi: 10.1177/1077559509350075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Johnson KM, Feeny NC, Treadwell KRH. The child PTSD symptom scale (CPSS): A preliminary examination of its psychometric properties. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:376–384. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feerick MM, Snow KL. The relationship between childhood sexual abuse, social anxiety, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in women. Journal of Family Violence. 2005;20(6):409–417. doi: 10.1007/s10896-005-7802-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Rothbaum BO, Riggs D, Murdock T. Treatment of PTSD in rape victims: A comparison between cognitive-behavioral procedures and counseling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:715–723. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.5.715. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.59.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foy DW, Madvig BT, Pynoos RS, Camiller AJ. Etiological factors in the development of posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Journal of School Psychology. 1996;34(2):133–145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-4405(96)00003-9. [Google Scholar]

- Giaconia RM, Reinherz HZ, paradis AD, Stashwick CK. Comorbidity of substance use disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder in adolescents. In: Ouimette P, Brown PJ, editors. Trauma and substance abuse: causes, consequences, and treatment of comorbid disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 227–242. [Google Scholar]

- Gold SN, Hughes DM, Swingle JM. Characteristics of childhood sexual abuse among female survivors in therapy. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1996;20(4):323–335. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(96)00001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1979;6:65–70. Retrieved from [ http://www.jstor.org/stable/4615733] [Google Scholar]

- Keane EM, Eick RW, Bechtold DW, Manson SM. Predictive and concurrent validity of the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire among American Indian adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1996;24(6):735–747. doi: 10.1007/BF01664737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston S, Raghavan C. The relationship of sexual abuse, early initiation of substance use, and adolescent trauma to PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22(1):65–68. doi: 10.1002/jts.20381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawyer SR, Ruggiero KJ, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Saunders BE. Mental health correlates of the victim-perpetrator relationship among interpersonally victimized adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21(10):1333–1353. doi: 10.1177/0886260506291654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev-Wiesel R, Amir M, Besser A. Posttraumatic growth among female survivors of childhood sexual abuse in relation to the perpetrator identity. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2005;10:7–17. doi: 10.1080/15325020490890606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucenko BA, Gold SN, Cott M. Relationship to perpetrator and posttraumatic symptomology among sexual abuse survivors. Journal of Family Violence. 2000;15:169–179. doi: 10.1023/A:1007542911767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon VV, Sartor CE, Pommer NE, Bucholz KK, Nelson EC, Madden PAF, Heath AC. Age at trauma exposure and PTSD risk in young adult women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23(6):811–814. doi: 10.1002/jts.20577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennen FE, Meadow D. The relationship of abuse characteristics to symptoms in sexually abused girls. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1995;10(3):259–274. doi: 10.1177/088626095010003002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olejnik S, Li J, Supattathum S, Huberty CJ. Multiple testing and statistical power with modified Bonferroni procedures. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1997;22:389–406. doi: 10.2307/1165229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Continuity of psychopathology in a community sample of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:1525–1535. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199511000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H, Thompson WD, Belanger A, Prusoff BA, Kidd KK. Comparison of the family history method to direct interview: Factors affecting the diagnosis of depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1982;4:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(82)90019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkonigg A, Kessler RC, Storz S, Wittchen HU. Traumatic events and post-traumatic stress disorder in the community; prevalence, risk factors and comorbidity. ACTA Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2000;101:46–59. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.101001046.x. 0.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.101001046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tebbutt J, Swanston H, Oates RK, O'Toole BI. Five years after child sexual abuse: persisting dysfunction and problems of prediction. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;36(3):330–339. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radnitz C, McGrath RE, Tirch DD, Willard J, Perez-Strumolo L, Festa J, et al. Lillian LB. Use of the Beck Depression Inventory in veterans with spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation Psychology. 1997;42(2):93–101. doi: 10.1037/0090-5550.42.2.93. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Junior. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM, Mazza JJ. Assessment of suicidal ideation in inner-city children and young adolescents: Reliability and validity of the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-JR. School Psychology Review. 1999;28(1):17–30. Retrieved from http://www.wce.wwu.edu/Depts/SPED/Forms/Kens%20Readings/Violence/Suicide/Assessment%20of%20Suicidal%20Ideation%20in%20InnerCity%20Children%20v.28%20iss.1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez N, Ryan S, Rowan AB, Foy DW. Posttraumatic stress disorder in a clinical sample of adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1996;20(10):943–952. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(96)00083-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romans SE, Martin JL, Anderson JC, O'Shea ML, Mullen The ‘anatomy’ of female child sexual abuse: who does what to young girls? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;30(3):319–325. doi: 10.3109/00048679609064993. Retrieved from http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/00048679609064993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields AL, Campfield DC, Miller CS, Howell RT, Wallace K, Weiss RD. Score reliability of adolescent screening measures: A meta-analytic inquiry. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2008;17(4):75–97. doi: 10.1080/15470650802292855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SH, Hyokyoung HG, Hazen AL. Childhood sexual abuse and adolescent substance use: A latent class analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;109:226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soylu N, Alpaslan AH. Suicidal behavior and associated factors in sexually abused adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review. 2013;35(2):253–257. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1312429902?accountid=14707. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins B, Bentovim A. The sexual abuse of male children and adolescents: a review of current research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1992;33:197–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC. Development of an adolescent alcohol and other drug use screening scale: Personal experience screening questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 1992;17:479–490. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90008-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Stinchfield RD, Henly GA, Schwartz RH. Validity of adolescent self-report of alcohol and other drug involvement. International Journal of the Addictions: Special Issue: Nonexperimental methods for studying addictions. 1991;25(11A):1379–1395. doi: 10.3109/10826089009068469. Retrieved from http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/10826089009068469?journalCode=sum. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Sas L, Wekerle C. Factors associated with the development of posttraumatic stress disorder among child victims of sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1994;18:37–50. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]