Abstract

Low cloning efficiency is considered to be caused by the incomplete or aberrant epigenetic reprogramming of differentiated donor cells in somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) embryos. Oxamflatin, a novel class of histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACi), has been found to improve the in vitro and full-term developmental potential of SCNT embryos. In the present study, we studied the effects of oxamflatin treatment on in vitro porcine SCNT embryos. Our results indicated that the rate of in vitro blastocyst formation of SCNT embryos treated with 1 μM oxamflatin for 15 h postactivation was significantly higher than all other treatments. Treatment of oxamflatin decreased the relative histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity in cloned embryos and resulted in hyperacetylation levels of histone H3 at lysine 9 (AcH3K9) and histone H4 at lysine 5 (AcH4K5) at pronuclear, two-cell, and four-cell stages partly through downregulating HDAC1. The suppression of HDAC6 through oxamflatin increased the nonhistone acetylation level of α-tubulin during the mitotic cell cycle of early SCNT embryos. In addition, we demonstrated that oxamflatin downregulated DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) expression and global DNA methylation level (5-methylcytosine) in two-cell-stage porcine SCNT embryos. The pluripotency-related gene POU5F1 was found to be upregulated in the oxamflatin-treated group with a decreased DNA methylation tendency in its promoter regions. Treatment of oxamflatin did not change the locus-specific DNA methylation levels of Sus scrofa heterochromatic satellite DNA sequences at the blastocyst stage. Meanwhile, our findings suggest that treatment with HDACi may contribute to maintaining the stable status of cytoskeleton-associated elements, such as acetylated α-tubulin, which may be the crucial determinants of donor nuclear reprogramming in early SCNT embryos. In summary, oxamflatin treatment improves the developmental potential of porcine SCNT embryos in vitro.

Introduction

Somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) is a useful tool for studying the potential mechanisms of nuclear epigenetic reprogramming. It opens up a wide range of biomedical applications. For example, the success of porcine cloning (Betthauser et al., 2000; Onishi et al., 2000; Polejaeva et al., 2000) may provide suitable donor organs for regenerative medicine and xenotransplantation (Prather et al., 2003). However, the low efficiency and higher developmental abnormalities of SCNT embryos are limiting its applications (Yang, X, et al., 2007). Intriguingly, cloned animals with an abnormal obese phenotype are likely to be due to incomplete epigenetic modifications rather than genetic mutations (Tamashiro et al., 2002). Because most of the reprogramming events of the donor cell nucleus are known to occur before zygotic gene activation (ZGA), most of the efforts to improve SCNT efficiency are focused on boosting the oocyte's reprogramming ability (Zuccotti et al., 2000).

The process of nuclear reprogramming involves a series of epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, histone acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination (Li et al., 2004; Rideout et al., 2001). Among the different epigenetic modifications, histone acetylation seems to be key for successful reprogramming (Rybouchkin et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2010), because the hyperacetylation state corresponds to chromatin relaxation, allowing a transcriptionally permissive state. Recently, a large number of histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi), such as trichostatin A (TSA) (Cervera et al., 2009; Ding et al., 2008; Enright et al., 2003; Wee et al., 2007), valproic acid (VPA) (Costa-Borges et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2011), Scriptaid (Wang et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2009, 2010), sodium butyrate (Das et al., 2010; Shi et al., 2003; Yang, F., et al., 2007), suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) (Ono et al., 2010) and m-carboxycinnamic acid bishydroxamide (CBHA) (Dai et al., 2010) have been shown to enhance in vitro and full-term development of SCNT embryos by modifying the epigenetic pattern of the donor nucleus.

Oxamflatin, a novel anticancer drug, is a HDACi (Kim et al., 1999). It has been shown that treatment with oxamflatin at appropriate concentrations and time points can significantly increase cloning efficiency in mouse (Ono et al., 2010), pig (Park et al., 2012), and cattle (Su et al., 2011). However, the mechanism underlying the improved in vitro development of SCNT embryos remains unclear. The aim of our study was to explore the effects of oxamflatin on the in vitro development of porcine SCNT embryos. We examined the global acetylation levels of histone H3 at lysine 9 (AcH3K9) and histone H4 at lysine 5 (AcH4K5), global DNA methylation and hydroxymethylcytosine levels, and acetylated α-tubulin levels at different stages of porcine SCNT embryos after oxamflatin treatment. The expression patterns of histone deacetylation, DNA methylation, and development-related genes were assessed during different developmental stages. Then we investigated the locus-specific DNA methylation levels of Sus scrofa heterochromatic satellite DNA sequences and POU5F1 promoter at blastocyst stage.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless specifically stated. All of the media and solutions were filtered by a 0.22-mm filter (Millipore, USA).

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were carried out according to Huazhong Agricultural University Animal Care and Use Committee Guidelines.

Primary cells establishment and nuclear donor cell preparation

Porcine fetal fibroblast (PFF) cell cultures were established according to the previously described methods with some modification (Lai and Prather, 2003). Briefly, 30-day-old fetuses were recovered from the uterus and rinsed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco). After removal of the head, limbs, intestine, liver, and heart, the remaining tissues were minced into pieces (1 mm3) using scissors in the PBS. Then, the minced tissue pieces were digested with collagenase (200 IU/mL) in a complete medium containing 82% Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM; Gibco), 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone), 1% glutathione (Gln), 1% MEM nonessential amino acids (NEAA), 1% sodium pyruvate (SP), and 2 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (Invitrogen, USA) for 3 h at 37.5°C and 5% CO2 in air. After digestion and washing, the cell pellets were seeded in a 60-mm culture plate (Corning, USA). The fibroblast cells were rinsed, trypsinized, and frozen in DMEM containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 20% FBS when the cells were at about 90% confluence. Donor cells were used at passages 4–10 and synchronized at the G0/G1 phase by contact inhibition for 2–5 days before SCNT. A single-cell suspension was prepared by trypsinization of the cultured cells and then resuspension in oocyte manipulation medium (MAN) [25 mM HEPES-buffered tissue culture medium-199 (TCM-199) with 3 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA)] prior to nuclear transfer.

Oocytes collection and in vitro maturation

The collection of porcine oocytes and in vitro maturation (IVM) were performed as described previously (Hao et al., 2004). Briefly, porcine ovaries were collected from prepubertal gilts at a slaughterhouse and then transported to the laboratory within 2–3 h in a thermos bottle with sterile saline at 35–38°C. Using an 18-gauge needle attached to a 10-mL syringe, cumulus–oocyte complexes (COCs) were aspirated from follicles with a diameter of 3–6 mm. Only oocytes surrounded by three to five layers of cumulus cells and with uniform cytoplasm were selected and rinsed three times in TL-HEPES medium containing 0.1% (wt/vol) polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). Then, 40–50 COCs were placed into 500 μL of maturation medium (TCM-199, Gibco) supplemented with 0.1% PVA (wt/vol), 3.05 mM d-glucose, 0.91 mM sodium pyruvate, 1 mg/mL gentamicin, 0.57 mM cysteine, 0.5 mg/mL luteinizing hormone (LH), 0.5 mg/mL follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), 10 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF), and 10% porcine follicular fluid (pFF). Subsequently, the medium containing COCs was transferred to a 24-well plate (Cloning, USA) covered by mineral oil, and the cells were cultured for 42–44 h at 37.5°C, 5% CO2 in air, and 100% humidity.

Somatic cell nuclear transfer

Briefly, after 42–44 h of IVM, cumulus cells were removed by 0.1% hyaluronidase TL-HEPES and by repeated pipetting. Only oocytes having an extruded first polar body (PB) with intact and uniform cytoplasm were used for nuclear transfer (NT). Matured metaphase II (MII) oocytes (30–40 oocytes/batch) were placed in MAN medium supplemented with 7.5 mg/mL cytochalasin B and fixed with a glass pipette having an outer diameter of around 120–140 μm and the inner diameter around 20 μm. With the aid of optical birefringence of an Oosight spindle-check system (CRI, Hopkinton, MA, USA), enucleation was accomplished by aspirating the PB and a small amount of cytoplasm containing the MII chromosomes using a beveled glass pipette with an inner diameter of 18–20 μm (Kim et al., 2012; Li et al., 2010). After that, a single intact donor cell with good morphology and size was injected into the perivitelline space and placed adjacent to the enucleated oocyte cytoplasm. Subsequently, fusion and activation of karyoplast–cytoplast complexes (KCCs) were accomplished synchronously in a chamber filled with fusion medium (supplemented with 0.3 M mannitol, 1.0 mM CaCl2·2H2O, 1.0 mM MgCl2·6H2O, and 0.5 mM HEPES, pH adjusted to 7.0–7.4) with 2 DC pulses of 1.2 kV/cm for 30 μsec on a BTX Electro Cell Manipulator 2001 (BTX, San Diego, CA). Approximately 30–40 reconstructed embryos were washed and cultured in porcine zygote medium-3 (PZM-3) supplemented with 3 mg/mL BSA, 20 μL/mL BME amino acid solution, and 10 μL/mL MEM nonessential amino acid solution (NEAA) and then covered with mineral oil and cultured at 39°C, 5% CO2 in air. In each experimental group, the ≥two-cell, ≥four-cell cleavage rates, and blastocyst rates were evaluated at 24, 48, and 144 h postactivation, respectively.

Preparation of oxamflatin and treatment protocol

Previous results in porcine SCNT showed that the chromatin decondensation that occurs during the pronuclear (PN) stage is crucial to allow HDACi to act. When using VPA or Scriptaid, the optimal duration of the treatment is between 14 and 16 h (Huang et al., 2011; Whitworth et al., 2011). Using this incubation time as reference, we treated the porcine SCNT embryos with various concentrations of oxamflatin (0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, or 10 μM) for 15 h postactivation. Then the culture medium was changed to PZM-3 without oxamflatin. The ≥two-cell, ≥four-cell cleavage rates, and blastocyst formation rates were evaluated. After finding the best suitable concentration of oxamflatin, the embryos were treated for different intervals (0, 6–8, 14–16, or 22–24 h). This optimized concentration and treatment duration were later used in the further experiments.

Histone deacetylase activity assay

Porcine embryos were treated with/without oxamflatin for 15 h and following the removal of zonae pellucidae by using acidic tyrode solution (pH 2.5); total protein from 20 embryos was extracted by using Nuclear Extraction Kit (Active Motif, 40010, Japan) following the whole-cell extract protocol. A histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity assay was performed as per the manufacturer's protocol (Active Motif, 56200, Japan). Briefly, 10 μL of HDAC substrate (500 μM) and 10 μL of HDAC assay buffer were added to 30 μL of total protein lysate and later incubated at 37°C for 1 h in the dark. The reaction was stopped by adding 50 μL of working HDAC Developing Solution and activity was measured on a fluorometer (Biotek, Elx 800, USA) using an excitation at 360 nm and an emission wavelength of 460 nm.

Immunofluorescence staining of embryos

Embryos were washed in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) containing 0.1% poly(vinylpyrrolidinone) (PVP), fixed for 1 h in 4% paraformaldehyde, and permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 in DPBS for 30 min at room temperature (RT). After washing three times, samples were blocked overnight at 4°C with 1% BSA prepared in DPBS and then incubated with the primary antibodies AcH3K9 (Abcam, USA, ab10812, diluted 1:1000), AcH4K5 (Abcam, USA, ab51997, diluted 1:500), Ac-α-tubulin (Lys40) XP™ Rabbit mAb (Cell Signaling, USA, #5335, diluted 1:800) for 1 h at RT, respectively. After washing three times, the embryos were treated with secondary antibodies of Alexa Fluor 555-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA, diluted 1:500) for AcH3K9, Alexa Fluor 488-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA, diluted 1:500) for AcH4K5, or Cy3-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA, diluted 1:500) for Ac-α-tubulin for 1 h at 37°C in the dark, respectively. Finally, the DNA was stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 5 min at RT.

For co-staining of global methylation and hydroxymethylcytosine, embryos were treated with 3 M HCl/PVP for 30 min at 37°C to denature DNA and neutralized with 100 mM Tris/PVP for 10 min at RT. After washing three times, samples were blocked overnight and co-stained overnight with primary antibodies, anti-5-methylcytosine (5-mC) mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb; Calbiochem, NA81, USA, diluted 1:500) and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5-hmC) antibody (Active Motif, 39769, Japan, diluted 1:500), and the secondary antibodies were mixed Alexa Fluor 488-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (1:500) and Cy3-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:500) for 5-mC and 5-hmC.

After this, samples were mounted on the glass slides and analyzed using an epifluorescence microscope (ZEISS, Observer. A1, Germany) equipped with a CoolSNAP™ 3.3 M digital camera (Photometrics, USA) with similar exposure adjustments. At least 10–15 embryos were processed for each group. The mean density [integrated optical density (IOD) sum/area sum] of fluorescence levels of samples was measured by using Image-Pro Plus 5.0 (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA from PFF cells, MII oocytes (100 oocytes), and embryos at the pronuclear stage (50 embryos), two-cell (30 embryos), four-cell (15 embryos), or the day-7 blastocysts (10 embryos), including three biological reps for each group, were collected for treatment (T-NT) and control (C-NT) groups by using the RNeasy Plus Micro Kit (Qiagen, #74034, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. Total RNA of these samples was carried out for reverse transcription (RT) reaction by using the RevertAid™ First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas, Canada) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The quantification of all the genes' mRNA levels were conducted by using SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II (TaKaRa, Japan) on CFX96 real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, USA). Briefly, total reaction mixture (20 μL) was consisted of 10 μL of SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II, 0.5 μL of each primer, 1 μL cDNA template, and 8 μL of ddH2O. The primers are listed in Table S1 (Supplementary Data are available at www.liebertpub.com/cell/). Real-time quantitative PCR was performed at the following thermal cycling conditions: 95°C for 2 min, followed by 45 cycles at 95°C for 10 sec, 55–62.5°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 15 sec. The melting protocol was a step cycle starting at 65°C and increasing to 95°C with 0.5°C/sec increments. Each transcript sample was quantified in three replicates by using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001), and the mRNA levels of all genes were normalized to the housekeeping gene β-actin.

Bisulfite sequencing analysis

The genomic DNA of the blastocyst samples (day 7) was treated with sodium bisulfite by using the EZ DNA Methylation-Direct™ Kit (Zymo Research, USA) in the C-NT and T-NT groups according to the manufacturer's protocol. Three blastocysts were transferred to 20 μL of digestion mixture and then incubated at 50°C for 3 h. The digested samples were added to 130 μL of CT Conversion Reagent and incubated for 8 min at 98°C and later 3.5 h at 64°C. Then modified DNA samples were desalted, purified, and finally eluted with 15 μL of elution buffer.

The BS-PCR reaction mixture was conducted in a volume of 20 μL and was consisted of 10 μL of Taq HS Mix (TaKaRa, Japan), 0.5 μL of each primer, 1 μL of modified DNA template, and 8 μL of ddH2O. The primers of the porcine satellite region (GenBank™ Z75640) or the POU5F1 promoter (GenBank™ CT737281.12) were synthesized as described previously (Kang et al., 2001a; Zhao et al., 2013). The cycling conditions consisted of one cycle at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation for 30 sec at 95°C, annealing for 30 sec at 55°C, extension for 20 sec at 72°C, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. Then the PCR products were purified using the Gel Purification Kit (Omega, USA).

The purified fragments were subcloned into pMD18-T vectors (TaKaRa, Japan), transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α, plated on Luria–Bertani (LB) agar containing ampicillin. After positive clones were confirmed by PCR, these clones later sent for sequencing (Sangon, Shanghai, China). Three independent amplification experiments were performed for C-NT and T-NT groups and six to ten clones were sequenced in each amplification experiment, so there were a total of 18–30 clones for each group. Bisulfite sequencing data was analyzed by using QUMA software (RIKEN, http://quma.cdb.riken.jp) according to the QUMA User's Manual.

Statistical analysis

Data expressed as percentages were analyzed by using a chi-squared test, whereas the other data were tested by Student's t-test, and p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Optimization of oxamflatin treatment for porcine SCNT embryos

To assess the effect of different concentrations of oxamflatin treatment on the developmental pattern of different embryonic stages, SCNT embryos were cultured in modified PZM-3, supplemented with 0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, or 10 μM oxamflatin for 15 h. The results showed that SCNT embryos displayed similar cleavage rates (around 62.9–68.9% of ≥two-cell and 46.1–51.6% ≥four-cell embryos, respectively) in all experimental groups, except those treated with 10 μM oxamflatin that, not only showed lower cleavage rates, but also lower blastocyst rates then the rest. The rate of blastocyst formation reached with 1 μM oxamflatin was significantly higher than that the control group (23.6% vs. 11.7%; p<0.05; Table S2). Then, 1 μM oxamflatin was used to test the optimum duration of treatment (0, 6–8, 14–16, or 22–24 h). The results showed that 1 μM oxamflatin for 14–16 h rendered a blastocyst rate significantly higher than in the control group (25.5% vs. 10.3%, p<0.05; Table 1). Therefore, 1 μM oxamflatin for 15 h was used in the rest of experiments.

Table 1.

Effect of 1 μM Oxamflatin Treatment Duration Time on In Vitro Development of Pig SCNT Embryos

| Treatment duration time | No. reconstructed | replications | Rate. (%)≥2-cell embryos | Rate. (%)≥4-cell embryos | Rate. (%) blastocysts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 h | 116 | 3 | 75 (64.7)a | 60 (51.7)b | 12 (10.3)a |

| 6–8 h | 124 | 4 | 77 (62.1)a | 65 (52.4)b | 19 (15.3)b |

| 14–16 h | 153 | 5 | 100 (65.3)a | 77 (50.3)b | 39 (25.5)c |

| 22–24 h | 133 | 3 | 84 (63.2)a | 66 (49.6)b | 23 (17.3)b |

Experiments were replicated three to five times. Data are presented as a synthesis of all experimental replicates; therefore, no error terms are associated with the data points (Isom et al., 2012). Different superscript letters in one line indicate significant differences at p<0.05.

Treatment with oxamflatin reduced the histone deacetylase activity

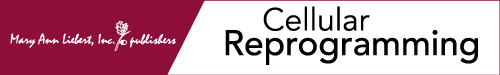

To investigate the effect of oxamflatin on the histone deacetylase activity, porcine SCNT embryos were treated with (T-NT) or without (C-NT) oxamflatin at the pronuclear stage (15 h, postactivation). Treatment with 1 μM oxamflatin for 15 h decreased the relative HDAC activity of SCNT embryos compared to the control (Fig. 1A; p<0.05).

FIG. 1.

Treatment of oxamflatin resulted in the histone hyperacetylation status of donor nucleus of porcine SCNT embryos. (A) Relative HDAC activities between nontreated (C-NT) and treated (T-NT) porcine SCNT embryos. Embryos were collected 15 h after activation. HDAC activities of embryos were measured using a short peptide substrate, BOC-(Ac) Lys-AMC. (B and C) Quantification of AcH3K9 and AcH4K5 mean fluorescence signals intensities of porcine SCNT embryos between C-NT and T-NT groups, respectively. Labeling intensity was expressed relative to that of the C-NT embryos. (D) The relative expression levels of histone deacetylation-related genes in MII oocytes and PFF cells. (E) The relative expression levels of HDAC1, -2, and -3 in MII, C-NT, and T-NT groups. Relative expression level of mRNA was calculated relative to β-actin. MII, oocytes in metaphase II stage; T-NT, SCNT embryos treated with 1 μM oxamflatin for 15 h postactivation; C-NT, nontreated SCNT embryos. Data are presented as mean±standard deviation (SD). (*) p<0.05; (**) p<0.01).

Treatment with oxamflatin leads to the histone hyperacetylation status of donor nucleus by downregulating HDAC1

To clarify the effects of oxamflatin on in vitro developmental potential of porcine SCNT embryos, we first compared the acetylation levels of two epigenetic markers (AcH3K9 and AcH4K5) by using immunofluorescence (IF) in pronuclear (15 h, postactivation), two-cell, four-cell, and blastocyst-stage embryos. The results indicated that the histone acetylation levels of AcH3K9 and AcH4K5 in pronuclear, two-cell and four-cell stage embryos were significantly increased by oxamflatin treatment (Fig. S1A, B, C). However, the acetylation levels of AcH3K9 and AcH4K5 were not different between the C-NT and T-NT groups at the blastocyst stage (Fig. S1D). These results were further confirmed by immunofluorescence analysis (Fig. 1B, C).

To better understand the effect of oxamflatin on the expression levels of histone deacetylation-related genes, we first compared the mRNA expression levels of different HDACs and sirtuins (HDAC1-11, and Sirt1, 2) between MII oocytes and PFF cells. The results demonstrated that higher mRNA levels of HDAC1, -2, -3, -8, -9, and -11 (p<0.01), Sirt1 and -2 (p<0.01), and HDAC7 and -10 (p<0.05) were observed in MII oocytes than in PFFs. There were no obvious differences between the two groups HDAC4 and HDAC5 (Fig. 1D; p>0.05); however, the mRNA expression level of HDAC6 was significantly higher in PFFs than that in MII oocytes (p<0.01). Overall, HDAC1, -2, and -3 have shown relatively higher expressions than other HDACs in PFFs and MII oocytes (Fig. 1D). The expression levels of HDAC1, -2, and -3 were further analyzed in MII oocytes and at the pronuclear stage in SCNT embryos (both C-NT and T-NT groups). The results indicated that the mRNA abundance of HDAC1 and HDAC2, but not HDAC3, was downregulated in porcine NT embryos at the pronuclear stage as compared with MII oocytes. Treatment with oxamflatin significantly downregulated the expression levels of HDAC1, but not HDAC2 and HDAC3 (Fig. 1E; p<0.05).

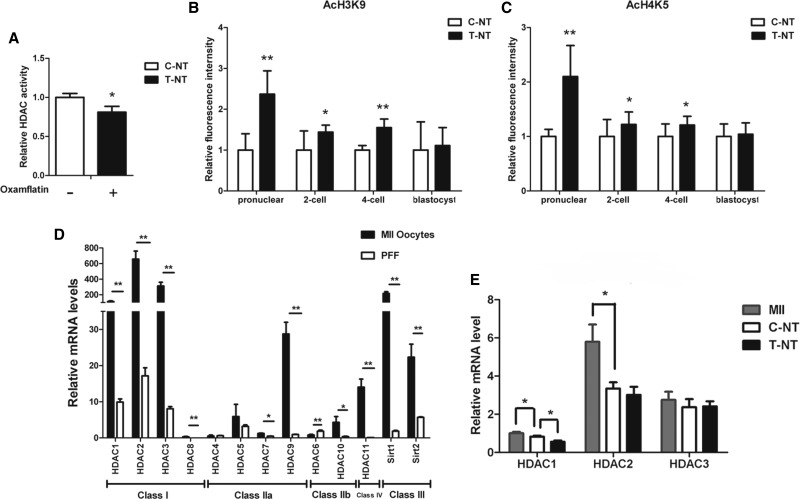

Oxamflatin induced non–histone protein acetylation of α-tubulin during the first and second mitotic cell cycle of porcine SCNT embryos

Because HDAC6 has previously shown relatively higher mRNA expression in PFF cells as compared with MII oocytes (Fig. 1D), we tested its expression in SCNT embryos at the two-cell (24–28 h, postactivation) and four-cell stages (48–52 h, postactivation). Unfortunately we did not have enough cDNA left to evaluate the expression levels of HDAC6 at the pronuclear (PN) stage. We found a significant downregulation of HDAC6 mRNA expression after oxamflatin treatment in two-cell- (Fig. 2A; p<0.05) and four-cell-stage embryos (Fig. 2B; p<0.05). Because the lack of HDAC6 results in the hyperacetylated α-tubulin level (Zhang et al., 2008), we checked the acetylation of α-tubulin during the first and second mitotic cell cycle in porcine SCNT embryos after oxamflatin treatment. The results indicated that during the first cell cycle, a high level of acetylated α-tubulin was found in the second meiotic midbody at prophase, spindle at anaphase, and the midbody in the interzonal region at telophase. During the second cell cycle, the spindle at metaphase showed a high level of acetylated α-tubulin in the oxamflatin-treated group, but not in the midbody at telophase, which showed no obvious difference in the acetylation level of α-tubulin between these two groups (Fig. 2C, D). These results were consistent with the analysis of mean fluorescence intensity (Fig. 2E, F).

FIG. 2.

Treatment with oxamflatin increased the acetylation levels of α-tubulin during the first and second mitotic cell cycle of porcine SCNT embryos through downregulating HDAC6. (A and B) The relative expression levels of HDAC6 at two-cell- (24–28 h, postactivation) and four-cell- (48–52 h, postactivation) stage embryos between C-NT and T-NT groups, respectively. The relative expression level of mRNA was normalized with β-actin. (C) Acetylation levels of α-tubulin at the first cell cycle after treatment with or without oxamflatin. Arrows indicate the second meiotic midbody at prophase, spindle at anaphase, and the midbody at telophase, respectively. (D) Acetylation levels of α-tubulin at the second cell cycle after treatment with or without oxamflatin. Arrows indicate the spindle at metaphase and the midbody at telophase, respectively. The experiments were repeated three times and each replication included at least 10–15 embryos. Representative examples are shown. Scale bar, 20 μm. (E and F) Quantification of mean fluorescence signal intensities of Ac-α-tubulin at the first cell cycle (prophase, anaphase, telophase) or the second cell cycle (metaphase, telophase) of porcine SCNT embryos between C-NT and T-NT groups. T-NT, SCNT embryos treated with 1 μM oxamflatin for 15 h postactivation; C-NT, nontreated SCNT embryos. Data are presented as mean±standard deviation (SD). (*) p<0.05; (**) p<0.01.

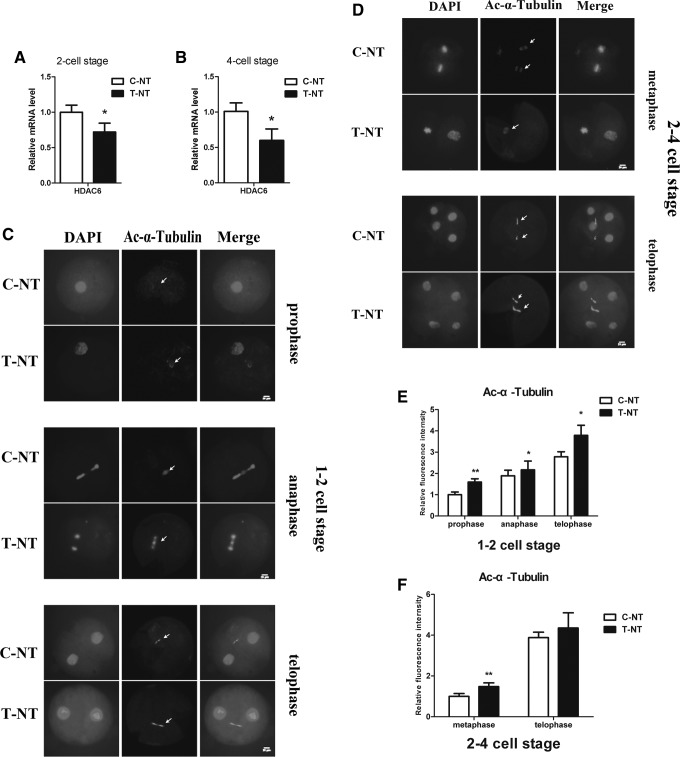

Oxamflatin decreased the global DNA methylation levels of two-cell-stage porcine SCNT embryos through downregulation of DNMT1

To determine whether oxamflatin treatment affected the global 5-mC and 5-hmC levels in porcine SCNT embryos, we performed immunocytofluorescent co-staining of 5-mC and 5-hmC at the two-cell and four-cell stages, but not at the PN stage when the SCNT embryos were undergoing the process of DNA replication. Our findings showed that the global 5-mC and 5-hmC levels were significantly reduced from the two-cell to the four-cell stage (Fig. 3A, B; p<0.01). In addition, oxamflatin treatment significantly decreased global 5-mC and 5-hmC levels at the two-cell stage (p<0.05), but not at the four-cell stage (Fig. 3A, B).

FIG. 3.

Treatment with oxamflatin resulted in decreased global DNA methylation levels of two-cell-stage porcine SCNT embryos through downregulation of DNMT1. (A) Immunofluorescence co-staining of global 5-mC and 5-hmC between C-NT and T-NT groups at the two-cell and four-cell stages. The experiments were repeated three times and each replication included at least 10–15 embryos. Representative examples are shown. Scale bar, 20 μm. (B) Quantification of mean fluorescence signal intensities of 5-mC and 5-hmC between C-NT and T-NT groups. (C) The relative mRNA expression levels of DNMT1, DNMT2, DNMT3a, and DNMT3b in MII oocytes. (D and E) The relative mRNA expression levels of DNMT1 at the two-cell- and four-cell-stage embryos between C-NT and T-NT groups, respectively. The relative expression level of mRNA was calculated with β-actin. T-NT, SCNT embryos treated with 1 μM oxamflatin for 15 h postactivation; C-NT, nontreated SCNT embryos. Data were presented as mean±standard deviation (SD). (*) p<0.05; (**) p<0.01.

Because the expression level of DNA methyltransferase-1 (DNMT1) was relatively higher in MII oocytes compared with other DNMTs (Fig. 3C; more than 50-fold; p<0.01), we examined the relative expression levels of DNMT1 in the two-cell- and four-cell-stage SCNT embryos after oxamflatin treatment. The results showed that mRNA expression of DNMT1 was significantly downregulated in two-cell-stage embryos (Fig. 3D; p<0.05) but not in four-cell-stage embryos when treated with oxamflatin (Fig. 3E; p>0.05).

The effect of oxamflatin on the expression levels of pluripotency-related genes in SCNT blastocysts

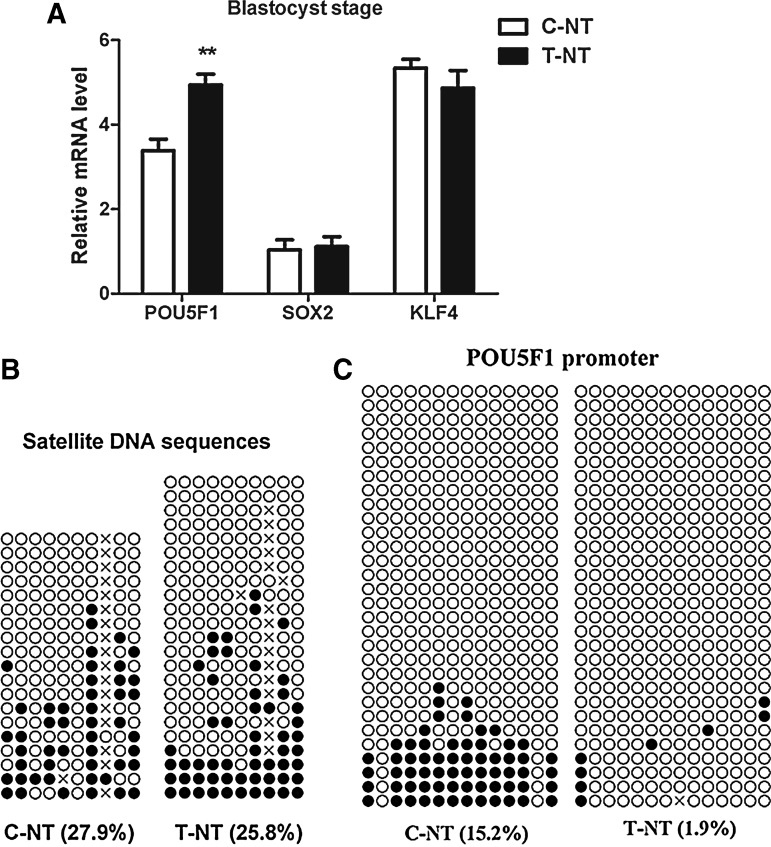

To investigate whether the increase in the blastocyst formation rate was correlated with the expression levels of pluripotency-related genes, the expression levels of three reprogramming factors, POU5F1, SOX2, and KLF4, were detected in blastocysts by using real-time quantitative PCR. As shown in Figure 4A, the expression level of POU5F1 was significantly higher in the oxamflatin treatment group than that of the control group (p<0.01). However, there were no significant differences in the relative expression levels of SOX2 and KLF4 between these two groups.

FIG. 4.

The effects of oxamflatin on the expression level of pluripotency-related genes and the locus-specific methylation status of satellite DNA sequences and POU5F1 promoter in porcine SCNT blastocysts. (A) Relative expression levels of POU1F, SOX2, and KLF4 in day-7 blastocysts derived from porcine SCNT embryos not treated (C-NT) or treated (T-NT) with 1 μM oxamflatin for 15 h postactivation. The relative expression level of mRNA was normalized to β-actin. Data are presented as mean±standard deviation (SD). (**) p<0.01. (B and C) Methylation profile analysis of porcine satellite sequences (GenBank accession no. Z75640.1) and POU5F1 promoter (GenBank accession no. CT737281.12) in day-7 porcine blastocysts between C-NT and T-NT groups, respectively. Open and filled circles, unmethylated and methylated CpG sites, respectively; horizontal lines of circles, one separated clone. Some CpG sites are absent from the satellite sequence in some clones due to mutations in the particular copies of the satellite sequences. Numbers at the bottom of the chart indicate the proportion of methylated CpG sites relative to the whole CpG sites counted.

The effects of oxamflatin on the locus-specific methylation status of satellite DNA sequences and POU5F1 promoter in porcine SCNT blastocysts

To understand the effect of oxamflatin treatment on the methylation status of locus-specific promoters or repetitive DNA sequences, we analyzed the DNA methylation levels of porcine satellite DNA sequences (GenBank™ Z75640) and POU5F1 promoter (GenBank™ CT737281.12) in SCNT blastocysts (day 7) by using bisulfite sequencing. The results showed that the methylation levels of porcine satellite DNA sequences did not display a significant difference between C-NT and T-NT groups (27.9 vs. 25.8%; p=0.36; Fig. 4B), and although the POU5F1 promoter showed low methylation levels in the T-NT group, but was not statistically significant (1.9% vs. 15.2%; p=0.39; Fig. 4C).

Discussion

The cytoplasm of MII oocytes can reprogram the differentiated somatic cell to a pluripotent state after SCNT (Hochedlinger and Jaenisch, 2002; Wilmut et al., 1997). However, not all enucleated MII oocytes have the competence to accomplish the correct reprogramming process. Therefore, the low cloning efficiency after SCNT is mainly attributed to the incomplete or aberrant epigenetic reprogramming of the differentiated donor nuclear genome (Rideout et al., 2001).

TSA, a widely available HDACi, has been shown to improve the cloning efficiency in pig (>40%; Cervera et al., 2009); however, its effect and application on cloning remains controversial. A recent study showed that treatment with 1 μM oxamflatin for 9 h after nuclear transfer could significantly improve the in vitro and full-term development of cloned mouse, at least without leading to obvious abnormalities, suggesting that oxamflatin may have a positive effect on mammalian cloning (Ono et al., 2010). Moreover, it has been found that oxamflatin treatment (1 μM oxamflatin after ionomycin for 12 h) can significantly enhance the in vitro developmental potential of cloned cattle embryos (Su et al., 2011). Recently, Park et al. (2012) found that treatment with 1 μM oxamflatin for 9 h after activation increased the developmental competence of porcine SCNT embryos both in vitro and in vivo (Park et al., 2012). Our results are consistent with most of the research published to date (Ono et al., 2010; Park et al., 2012; Su et al., 2011). Although Park et al. (2012) reported a considerably higher blastocyst formation rate than the present study, the more obvious reason for this difference is the distinguishing statistical method used to evaluate cleavage rate and blastocyst formation rate.

To clarify the mechanism of how oxamflatin improves the in vitro development of the SCNT embryos, we first focused on histone acetylation, which plays a crucial role in the process of somatic cell nuclear reprogramming (Wee et al., 2007; Yamanaka et al., 2009). Earlier studies have shown that the acetylated status of lysine residues within core histones (AcH3K9, AcH3K14, AcH3K18, AcH4K8, AcH4K5, etc.) can be modified by HDACi treatment in reconstructed embryos and donor cells of pig (Cervera et al., 2009; Das et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2011; Martinez-Diaz et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2010), cattle (Iager et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011), and mouse (Bui et al., 2010; Costa-Borges et al., 2010). Furthermore, it is well accepted that increasing histone acetylation levels on most amino acid residues could form a transcriptionally permissive state by loosening the binding of nucleosomes to DNA, relaxing chromatin structure, and facilitating access of various factors to nucleosomes (Rybouchkin et al., 2006). Previous data suggest that the in vitro and full-term development rates of cloning embryos of various species are likely to be influenced by the inhibition of HDAC activity. Our results also support the notion that the inhibitory activity of HDAC is a critical factor for the in vitro development rate of cloning embryos (Pasque et al., 2011).

The stable status of histone acetylation is controlled by balancing the expression of histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and HDACs. HDACs are comprised of four classes based on homology. Class I HDACs include HDAC1, -2, -3, and -8; class II enzymes are divided into two classes, class IIa (HDAC4, -5, -7, and -9) and class IIb (HDAC6 and -10); class III HDACs include Sirt1–7, which require the co-factor nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) for activity; and class IV HDAC includes only HDAC11 (Blackwell et al., 2008). In a previous study, HDAC1 appeared to play a vital role in the overall acetylation state of hyperacetylated histones of preimplantation mouse embryos based on an inverse correlation between HDAC1 (but not HDAC2, −3) expression and acetylation state of H4K5 (Ma and Schultz, 2008). Our results are consistent with this study by showing significantly downregulated expression of HDAC1 after oxamflatin treatment. Therefore, we hypothesized that oxamflatin treatment may lead to the histone hyperacetylation status of H3K9 and H4K5, at least in part by downregulating HDAC1 in the early developmental stage of SCNT embryos. However, because both HDAC1 and HDAC2 were reduced in porcine NT embryos at the pronuclear stage as compared with MII oocytes (Fig. 1E), we cannot exclude a possibility that HDAC2 may be contributing to this site-specific hyperacetylation. Addition of an appropriate control group (at least IVF embryos) and the gene knockdown/out models for HDAC1 or HDAC2 in the future should be used to better understand these results.

Ono et al. (2010) have shown that compared to VPA, an inhibitor of classes I and IIa HDACs, oxamflatin has an additional function in restraining the activity of class IIb HDACs, suggesting it is more important for improving mouse cloning efficiency (Ono et al., 2010). A recent study from Matsubara et al. (2013) indicated that a TSA-treated mouse zygote enhanced the acetylation of α-tubulin in the entire cytoplasm and the midbody structure (Matsubara et al., 2013). α-Tubulin is the main component of microtubules and contributes to the formation of cytoskeleton, spindle, and midbody and appears in a cell cycle–specific pattern in mouse embryos (Schatten et al., 1988). Moreover, acetylation of α-tubulin has been implicated in regulating microtubule stability and function (Piperno et al., 1987; Schatten et al., 1988). HDAC6, one of the members of class IIb HDACs, functions as a microtubule-associated deacetylase, and its downregulation increases α-tubulin acetylation (Hubbert et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2008). Our study confirmed these results in SCNT embryos because treatment of oxamflation increased the acetylation levels of α-tubulin by suppressing the mRNA level of HDAC6. The results from this study reveal that treatment with oxamflatin may contribute to maintaining the stable status of the cytoskeleton-associated element acetylated α-tubulin, which appears crucial for SCNT embryos.

DNA methylation is another crucial epigenetic mechanism that exists extensively in the mammalian genome and is modulated during the reprogramming process after SCNT. DNA methylation is maintained through the activity of DNMTs, including DNMT1, DNMT2, DNMT3a, DNMT3b, and DNMT3L. DNMT1 plays a vital role in methylation maintenance during the replication of the newly formed DNA strands (Okano et al., 1999; Sharif et al., 2007). Previous studies found that treatment with TSA significantly downregulated DNMT1 mRNA and protein expression in different cell types (Choi et al., 2010; Januchowski et al., 2007; Xiong et al., 2005). Moreover, TSA and oxamflatin are structurally related HDAC inhibitors, all derived from hydroxamic acid (Blackwell et al., 2008). Consistent with these findings, our study revealed that treatment of oxamflatin downregulating DNMT1 expression in two-cell embryos and the reduction of global 5-mC level contributing to the chromatic-relaxed status compatible with transcriptional activity. Indeed, treatment with 1 μM oxamflatin for 96 h also significantly downregulated DNMT1 expression without leading to obvious changes in the morphology of porcine fetal fibroblast cells (data not shown).

Recent studies suggest that Tet (ten eleven translocation) family proteins can convert 5mC to 5hmC (also known as the “sixth base”) (Ito et al., 2010; Tahiliani et al., 2009), and this process may involve in the preferential demethylation of paternal genome in mouse zygotes. During the mouse preimplantation development, 5-hmC displays a replication-dependent dilution pattern (Inoue and Zhang, 2011), and our results showed that 5-mC presented a reduction trend from the two-cell to the four-cell stage, and the change of 5-hmC similar to 5-mC (Fig. 3A). Because 5-mC is the precursor of 5-hmC, it seems that the reduction of 5-hmC after treatment with oxamflatin is due to the result of reduced 5-mC; however, whether oxamflatin is a direct cause of reduced 5-hmC signals (independent of 5-mC) needs further investigations.

To evaluate the quality of blastocysts, we analyzed the mRNA expression levels of the pluripotency-related genes POU5F1, SOX2, and KLF4 in SCNT blastocysts after oxamflatin treatment. The mRNA level of POU5F1, a key regulator of pluripotency (Nichols et al., 1998), was significantly higher in the oxamflatin-treated group (Fig. 4A), and this finding is consistent with a previous study (Park et al., 2012). The expression level of POU5F1 correlates tightly with the methylation status of its promoter (Gidekel and Bergman, 2002; Hattori et al., 2004, Simonsson and Gurdon, 2004). Although, the methylation level of the POU5F1 promoter showed no apparent difference between treated and nontreated groups, a decreased tendency may explain the higher expression level of POU5F1 that we found in the oxamflatin treatment group. SOX2 cooperation with POU5F1 has been shown to maintain the pluripotent embryonic stem cell phenotype (Rodda et al., 2005); however, oxamflatin treatment appeared to have no direct effect on the expression of SOX2 and KLF4 in porcine SCNT embryos.

Satellite DNA, the component of functional centromeres, is composed of highly conserved tandem repeat DNA sequences in the genome and forms the main structural constituent of heterochromatin (Charlesworth et al., 1994). Reports have shown that satellite DNA offers specific binding proteins and plays an important role in the structural changes of the genetic material, gene regulation, and cell differentiation (Palomeque and Lorite, 2008). A study revealed that cloned bovine embryos showed aberrant hypermethylation in the satellite region as compared with the IVF blastocysts (Kang et al., 2001b). Furthermore, Zhang and his colleagues also found that in bovines, the DNA methylation level of satellite sequences between IVF blastocysts and oxamflatin-treated NT blastocysts was significantly lower than that of nontreated NT blastocysts (Su et al., 2011). Inconsistently, we found that there were no significant differences in the methylation levels of porcine satellite regions in 7-day-old SCNT blastocysts between the oxamflatin-treated and nontreated groups (27.9 vs. 25.8%; Fig. 4B). Perhaps there could be a species difference (Kang et al., 2001a); however, in vivo or in vitro fertilized embryos should be used as controls to better understand these results. Moreover, a recent study showed that certain repetitive elements seemed more resistant to demethylation after nuclear transfer as compared to the dynamics at fertilization (Chan et al., 2012). This result can partly account for the insignificant differences of the methylation level of porcine satellite DNA sequences between oxamflatin-treated and nontreated groups.

In summary, our study indicates that treatment of 1 μM oxamflatin for 15 h postactivation improves the rate of blastocyst formation and in vitro development of cloned porcine embryos. Furthermore, treatment of oxamflatin results in histone hyperacetylation of reconstructed embryos partly by downregulating HDAC1; it decreases global DNA methylation levels at the two-cell stage by downregulating DNMT1 and increases the acetylation level of α-tubulin during the first and second cell cycle of porcine SCNT embryos by suppressing HDAC6. A series of changes in related gene expression and proteins before the four-cell stage (ZGA) may play a critical role in the development of better blastocysts with higher expression of POU5F1. These results further corroborate the notion that treatment with oxamflatin has a positive effect on ZGA to support more accurate remodeling and reprogramming regulation in early porcine SCNT embryos (Park et al., 2012). However, absence of a control group (IVF embryos) is a critical limitation, and it is recommended that further research be undertaken involving this issue. Meanwhile, studies on the role of cytoskeleton-associated elements in the nuclear transfer reprogramming process, such as tubulin and tubulin-related protein, and on nuclear actin and actin-binding proteins (Miyamoto et al., 2011, 2013a, 2013b) are needed. These studies could guide in gaining insights into the potential mechanism of reprogramming when donor cells are transferred into enucleated MII oocytes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Project for Breeding of Transgenic Pig (grant no. 2013ZX08006-002), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant no. 2013PY032), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31000996, 31172179, 3120764), the National Research Program of China (grant no. 2014CB138500), and Wuhan Youth Chenguang Program of Science and Technology (grant no. 2014070404010204).

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Betthauser J., Forsberg E., Augenstein M., Childs L., Eilertsen K., Enos J., Forsythe T., Golueke P., Jurgella G., Koppang R., Lesmeister T., Mallon K., Mell G., Misica P., Pace M., Pfister-Genskow M., Strelchenko N., Voelker G., Watt S., Thompson S., and Bishop M. (2000). Production of cloned piglets from in vitro systems. Nat. Biotechnol. 18, 1055–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell L., Norris J., Suto C.M., and Janzen W.P. (2008). The use of diversity profiling to characterize chemical modulators of the histone deacetylases. Life Sci. 82, 1050–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui H.T., Wakayama S., Kishigami S., Park K.K., Kim J.H., Thuan N.V., and Wakayama T. (2010). Effect of Trichostatin A on chromatin remodeling, histone modifications, DNA replication, and transcriptional activity in cloned mouse embryos. Biol. Reprod. 83, 454–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervera R.P., Marti-Gutierrez N., Escorihuela E., Moreno R., and Stojkovic M. (2009). Trichostatin A affects histone acetylation and gene expression in porcine somatic cell nucleus transfer embryos. Theriogenology 72, 1097–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan M.M., Smith Z.D., Egli D., Regev A., and Meissner A. (2012). Mouse ooplasm confers context-specific reprogramming capacity. Nat. Genet. 44, 978–980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B., Sniegowski P., and Stephan W. (1994). The evolutionary dynamics of repetitive DNA in eukaryotes. Nature 371, 215–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J.H., Min N.Y., Park J., Kim J.H., Park S.H., Ko Y.J., Kang Y., Moon Y.J., Rhee S., Ham S.W., Park A.J., and Lee K.H. (2010). TSA-induced DNMT1 down-regulation represses hTERT expression via recruiting CTCF into demethylated core promoter region of hTERT in HCT116. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 391, 449–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Borges N., Santalo J., and Ibanez E. (2010). Comparison between the effects of valproic acid and trichostatin A on the in vitro development, blastocyst quality, and full-term development of mouse somatic cell nuclear transfer embryos. Cell. Reprogram. 12, 437–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X., Hao J., Hou X., Hai T., Yu Y., Jouneau A., Wang L., and Zhou Q. (2010). Somatic nucleus reprogramming is significantly improved by m-carboxycinnamic acid bishydroxamide, a histone deacetylase inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 31002–31010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das Z.C., Gupta M.K., Uhm S.J., and Lee H.T. (2010). Increasing histone acetylation of cloned embryos, but not donor cells, by sodium butyrate improves their in vitro development in pigs. Cell. Reprogram. 12, 95–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X., Wang Y., Zhang D., Wang Y., Guo Z., and Zhang Y. (2008). Increased preimplantation development of cloned bovine embryos treated with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine and trichostatin A. Theriogenology 70, 622–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright B.P., Kubota C., Yang X., and Tian X.C. (2003). Epigenetic characteristics and development of embryos cloned from donor cells treated by trichostatin A or 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. Biol. Reprod. 69, 896–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidekel S., and Bergman Y. (2002). A unique developmental pattern of Oct-3/4 DNA methylation is controlled by a cis-demodification element. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 34521–34530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y., Lai L., Mao J., Im G.S., Bonk A., and Prather R.S. (2004). Apoptosis in parthenogenetic preimplantation porcine embryos. Biol. Reprod. 70, 1644–1649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori N., Nishino K., Ko Y., Hattori N., Ohgane J., Tanaka S., and Shiota K. (2004). Epigenetic control of mouse Oct-4 gene expression in embryonic stem cells and trophoblast stem cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 17063–17069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochedlinger K., and Jaenisch R. (2002). Monoclonal mice generated by nuclear transfer from mature B and T donor cells. Nature 415, 1035–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Tang X., Xie W., Zhou Y., Li D., Yao C., Yao C., Zhou Y., Zhu J., Lai L., Ouyang H., and Pang D. (2011). Histone deacetylase inhibitor significantly improved the cloning efficiency of porcine somatic cell nuclear transfer embryos. Cell. Reprogram. 14, 513–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbert C., Guardiola A., and Shao R. (2002). HDAC6 is a microtubule-associated deacetylase. Nature 417, 455–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iager A.E., Ragina N.P., Ross P.J., Beyhan Z., Cunniff K., Rodriguez R.M., and Cibelli J.B. (2008). Trichostatin A improves histone acetylation in bovine somatic cell nuclear transfer early embryos. Cloning Stem Cells 10, 371–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue A., and Zhang Y. (2011). Replication-dependent loss of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mouse preimplantation embryos. Science 334, 194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isom S.C., Li R.F., Whitworth K.M., and Prather R.S. (2012). Timing of first embryonic cleavage is a positive indicator of the in vitro developmental potential of porcineembryos derived from in vitro fertilization, somatic cell nuclear transfer and parthenogenesis. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 79, 197–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S., D'Alessio A.C., Taranova O.V., Hong K., Sowers L.C., and Zhang Y. (2010). Role of Tet proteins in 5mC to 5hmC conversion, ES-cell self-renewal and inner cell mass specification. Nature 466, 1129–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Januchowski R., Dabrowski M., Ofori H., and Jagodzinski P.P. (2007). Trichostatin A down-regulates DNA methyltransferase 1 in Jurkat T cells. Cancer Lett. 246, 313–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin D., Tan H.J., Lei T., Gan L., Chen X.D., Long Q.Q., Feng B., and Yang Z.Q. (2009). Molecular cloning and characterization of porcine sirtuin genes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 153, 348–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y.K., Koo D.B., Park J.S., Choi Y.H., Kim H.N., Chang W.K., Lee K.K., and Han Y.M. (2001a). Typical demethylation events in cloned pig embryos. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 39980–39984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y.K., Koo D.B., Park J.S., Choi Y.H., Kim H.N., Chang W.K., Lee K.K., and Han Y.M. (2001b). Aberrant methylation of donor genome in cloned bovine embryos. Nat. Genet. 28, 173–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E.Y., Park M.J., Park H.Y., Noh E.J., Noh E.H., Park K.S., Lee J.B., Jeong C.J., Riu K.Z., and Park S.P. (2012). Improved cloning efficiency and developmental potential in bovine somatic cell nuclear transfer with the oosight imaging system. Cell. Reprogram. 14, 305–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.B., Lee K.H., Sugita K., Yoshida M., and Horinouchi S. (1999). Oxamflatin is a novel antitumor compound that inhibits mammalian histone deacetylase. Oncogene 18, 2461–2470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar B.M., Maeng G.H., Lee Y.M, Lee J.H., Jeon B.G., Ock S.A., Kang T., and Rho G.J. (2012). Epigenetic modification of fetal fibroblasts improves developmental competency and gene expression in porcine cloned embryos. Vet. Res. Commun. 37, 19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai L.X., and Prather R.S. (2003). Production of cloned pigs by using somatic cells as donors. Cloning Stem Cells 5, 233–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Du W., and Li N. (2004). Epigenetic reprogramming in mammalian nuclear transfer. Chin. Sci. Bull. 49, 766–771 [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Liu J., Dai J., Xing F., Fang Z., Zhang T., Shi Z., Zhang D., and Chen X. (2010). Production of cloned miniature pigs by enucleation using the spindle view system. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 45, 608–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K.J., and Schmittgen T.D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(T) (−Delta Delta C) method. Methods 25, 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma P., and Schultz R.M. (2008). Histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) regulates histone acetylation, development, and gene expression in preimplantation mouse embryos. Dev. Biol. 319, 110–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Diaz M.A., Che L., Albornoz M., Seneda M.M., Collis D., Coutinho A.R., El-Beirouthi N., Laurin D., Zhao X., and Bordignon V. (2010). Pre- and postimplantation development of swine-cloned embryos derived from fibroblasts and bone marrow cells after inhibition of histone deacetylases. Cell. Reprogram. 12, 85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara K., Lee A.R., Kishigami S., Ito A., Matsumoto K., Chi H., Nishino N., Yoshida M., and Hosoi Y. (2013). Dynamics and regulation of lysine-acetylation during one-cell stage mouse embryos. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 434, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto K., Pasque V., Jullien J., and Gurdon J.B. (2011). Nuclear actin polymerization is required for transcriptional reprogramming of Oct4 by oocytes. Genes Dev. 25, 946–958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto K., and Gurdon J.B. (2013a). Transcriptional regulation and nuclear reprogramming: Roles of nuclear actin and actin-binding proteins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 70, 3289–3302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto K., Teperek M., Yusa K., Allen G.E., Bradshaw C.R., and Gurdon J.B. (2013b). Nuclear Wave1 is required for reprogramming transcription in oocytes and for normal development. Science 341, 1002–1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols J., Zevnik B., Anastassiadis K., Niwa H., Klewe-Nebenius D., Chambers I., Scholer H., and Smith A. (1998). Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell 95, 379–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano M., Bell D.W., Haber D.A., and Li E. (1999). DNA methyltransferases DNMT3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo methylation and mammalian development. Cell 99, 247–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishi A., Iwamoto M., Akita T., Mikawa S., Takeda K., Awata T., Hanada H., and Perry A.C. (2000). Pig cloning by microinjection of fetal fibroblast nuclei. Science 289, 1188–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono T., Li C., Mizutani E., Terashita Y., Yamagata K., and Wakayama T. (2010). Inhibition of class IIb histone deacetylase significantly improves cloning efficiency in mice. Biol. Reprod. 83, 929–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomeque T., and Lorite P. (2008). Satellite DNA in insects: A review. Heredity 100, 564–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.J., Park H.J., Koo O.J., Choi W.J., Moon J., Kwon D.K., Kang J.T., Kim S., Choi J.Y., Jang G., and Lee B.C. (2012). Oxamflatin improves developmental competence of porcine somatic cell nuclear transfer embryos. Cell. Reprogram. 14, 398–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasque V., Jullien J., Miyamoto K., Halley-Stott R.P., and Gurdon J.B. (2011). Epigenetic factors influencing resistance to nuclear reprogramming. Trends Genet. 27, 516–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piperno G., LeDizet M., and Chang X.J. (1987). Microtubules containing acetylated alpha-tubulin in mammalian cells in culture. J. Cell. Biol. 104, 289–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polejaeva I.A., Chen S.H., Vaught T.D., Page R.L., Mullins J., Ball S., Dai Y., Boone J., Walker S., Ayares D.L., Colman A., and Campbell K.H.S. (2000). Cloned pigs produced by nuclear transfer from adult somatic cells. Nature 7, 86–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prather R.S., Hawley R.J., Carter D.B., Lai L., and Greenstein J.L. (2003). Transgenic swine for biomedicine and agriculture. Theriogenology 59, 115–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout W.M., 3rd, Eggan K., and Jaenisch R. (2001). Nuclear cloning and epigenetic reprogramming of the genome. Science 293, 1093–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodda D.J., Chew J.L., Lim L.H., Loh Y.H., Wang B., Ng H.H., and Robson P. (2005). Transcriptional regulation of Nanog by Oct4 and Sox2. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 24731–24737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybouchkin A., Kato Y., and Tsunoda Y. (2006). Role of histone acetylation in reprogramming of somatic nuclei following nuclear transfer. Biol. Reprod. 74, 1083–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatten G., Simerly C., Asai D.J., Szuke E., Cooke P., and Schatten H. (1988). Acetylated alpha-tubulin in microtubules during mouse fertilization and early development. Dev. Biol. 130, 74–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif J., Muto M., Takebayashi S., Suetake I., Iwamatsu A., Endo A., Shinga J., Mizutani-Koseki Y., Toyoda T., Okamura K., Tajima S., Mitsuya K., Okano M., and Koseki H. (2007). The SRA protein Np95 mediates epigenetic inheritance by recruiting DNMT1 to methylated DNA. Nature 450, 908–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W., Hoeflich A., Flaswinkel H., Stojkovic M., Wolf E., and Zakhartchenko V. (2003). Induction of a senescent-like phenotype does not confer the ability of bovine immortal cells to support the development of nuclear transfer embryos. Biol. Reprod. 69, 301–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsson S., and Gurdon J. (2004). DNA demethylation is necessary for the epigenetic reprogramming of somatic cell nuclei. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 984–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su J., Wang Y., Li Y., Li R., Li Q., Wu Y., Quan F., Liu J., Guo Z., and Zhang Y. (2011). Oxamflatin significantly improves nuclear reprogramming, blastocyst quality, and in vitro development of bovine SCNT embryos. PLoS One 6, e23805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahiliani M., Koh K.P., Shen Y., Pastor W.A., Bandukwala H., Brudno Y., Agarwal S., Iyer L.M., Liu D.R., Aravind L., and Rao A. (2009). Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science 324, 930–935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamashiro K.L.K., Wakayama T., Akutsu H., Yamazaki Y., Lachey J.L., Wortman M.D., Seeley R.J., D'Alessio D.A., Woods S.C., Yanagimachi R., and Sakai R.R. (2002). Cloned mice have an obese phenotype not transmitted to their offspring. Nat. Med. 8, 262–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.J., Zhang H., Wang Y.S., Xu W.B., Xiong X.R., Li Y.Y., Su J.M., Hua S., and Zhang Y. (2011). Scriptaid improves in vitro development and nuclear reprogramming of somatic cell nuclear transfer bovine embryos. Cell. Reprogram. 13, 431–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee G., Shim J.J., Koo D.B., Chae J.I., Lee K.K., and Han Y.M. (2007). Epigenetic alteration of the donor cells does not recapitulate the reprogramming of DNA methylation in cloned embryos. Reproduction 134, 781–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth K.M., Zhao J., Spate L.D., Li R., and Prather R.S. (2011). Scriptaid corrects gene expression of a few aberrantly reprogrammed transcripts in nuclear transfer pig blastocyst stage embryos. Cell. Reprogram. 13, 191–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmut I., Schnieke A.E., McWhir J., Kind A.J., and Campbell K.H.S. (1997). Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells. Nature 385, 810–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y., Dowdy S.C., Podratz K.C., Jin F., Attewell J.R., Eberhardt N.L., and Jiang S.W. (2005). Histone deacetylase inhibitors decrease DNA methyltransferase-3B messenger RNA stability and down-regulate de novo DNA methyltransferase activity in human endometrial cells. Cancer Res. 65, 2684–2689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka K., Sugimura S., Wakai T., Kawahara M., and Sato E. (2009). Acetylation level of histone H3 in early embryonic stages affects subsequent development of miniature pig somatic cell nuclear transfer embryos. J. Reprod. Develop. 55, 638–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Hao R., Kessler B., Brem G., Wolf E., and Zakhartchenko V. (2007). Rabbit somatic cell cloning: Effects of donor cell type, histone acetylation status and chimeric embryo complementation. Reproduction 133, 219–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Smith S.L., Tian X.C., Lewin H.A., Renard J.P., and Wakayama T. (2007). Nuclear reprogramming of cloned embryos and its implications for therapeutic cloning. Nat. Genet. 39, 295–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Kwon S.H., Yamaguchi T., Cubizolles F., Rousseaux S., Kneisse,l M., Cao C., Li N., Cheng H.L., Chua K., Lombard D., Mizeracki A., Matthias G., Frederick W.A., Khochbin S., and Matthias P. (2008). Mice lacking histone deacetylase 6 have hyperacetylated tubulin but are viable and develop normally. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 1688–1701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Hao Y., Ross J.W., Spate L.D., Walters E.M., Samuel M.S., Rieke A., Murphy C.N., and Prather R.S. (2010). Histone deacetylase inhibitors improve in vitro and in vivo developmental competence of somatic cell nuclear transfer porcine embryos. Cell. Reprogram. 12, 75–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Ross J.W., Hao Y., Spate L.D., Walters E.M., Samuel M.S., Rieke A., Murphy C.N., and Prather R.S. (2009). Significant improvement in cloning efficiency of an inbred miniature pig by scriptaid treatment after somatic cell nuclear transfer. Biol. Reprod. 81, 525–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M., Rivera R.M., and Prather R.S. (2013). Locus-specific DNA methylation reprogramming during early porcine embryogenesis. Biol. Reprod. 88, 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccotti M., Garagna S., and Redi C.A. (2000). Nuclear transfer, genome reprogramming and novel opportunities in cell therapy. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 23, 623–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.