Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) utilize (at least) two signal transduction pathways to elicit cellular responses including the classic G protein-dependent, and the more recently discovered β-arrestin-dependent, signaling pathways. In human and murine models of asthma, agonist-activation of β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) or Protease-activated-receptor-2 (PAR2) results in relief from bronchospasm via airway smooth muscle relaxation. However, chronic activation of these receptors, leads to pro-inflammatory responses. One plausible explanation underlying the paradoxical effects of β2AR and PAR2 agonism in asthma is that the beneficial and harmful effects are associated with distinct signaling pathways. Specifically, G protein-dependent signaling mediates relaxation of airway smooth muscle, whereas β-arrestin-dependent signaling promotes inflammation. This review explores the evidence supporting the hypothesis that β-arrestin-dependent signaling downstream of β2AR and PAR2 is detrimental in asthma and examines the therapeutic opportunities for selectively targeting this pathway.

INTRODUCTION

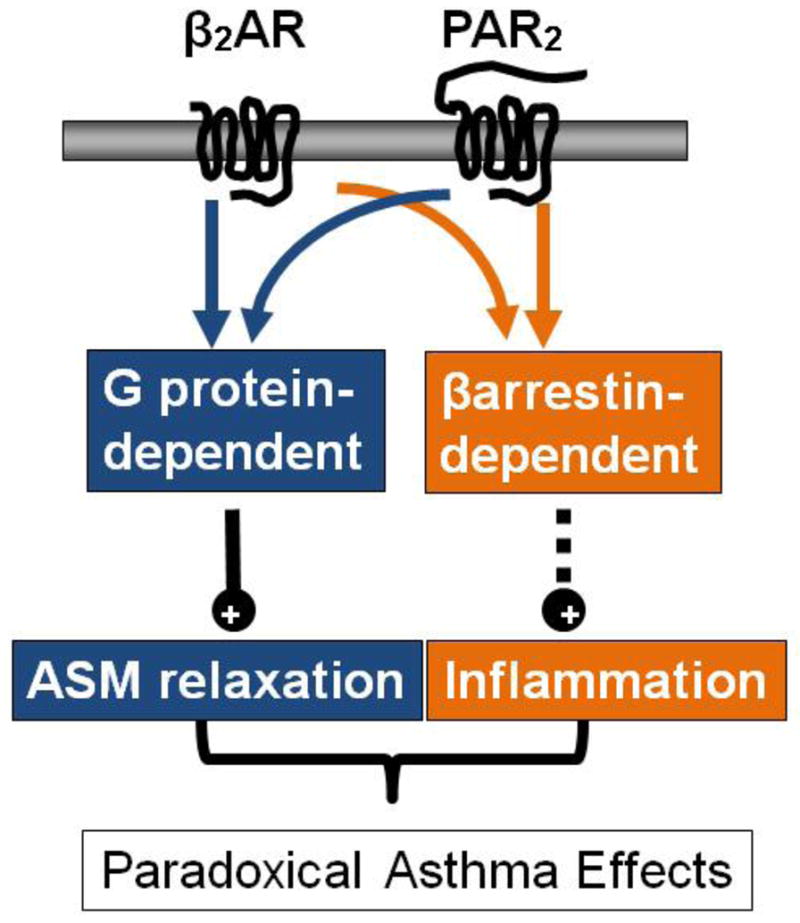

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by airway inflammation, hyperresponsiveness and remodeling [1]. Airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), a measure of bronchoconstrictor responsiveness, is associated with debilitating asthma signs and symptoms such as coughing, wheezing and shortness of breath. Beta-2-adrenergic receptor (β2-AR) agonist (β-agonist) administration is the mainstay therapy during bronchospastic episodes, providing significant relief to asthmatics [2]. However, chronic β-agonist therapy has also been associated with loss of asthma control, worsening of disease and increased morbidity and mortality (reviewed in [3]). Activation of Protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR2), which promotes bronchorelaxation, has also been explored as a treatment for asthma. However, similar to the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) paradox, murine studies have shown that PAR2 activation can play diametrically opposed roles in allergic asthma providing both potent bronchorelaxation and increased inflammation [4]. Activation of dual independent signaling pathways by agonist binding to a single receptor may underlie these respective paradoxical effects. It is well known that signal transduction at the β2AR and PAR2 (as well as a multitude of other GPCRs) occurs through classic G-protein-dependent signaling, as well as via the more recently described β-arrestin-dependent signaling pathway (Fig. 1) [5,6]. Interestingly, the two pathways are also temporally separable, with β-arrestin signaling sometimes occurring earlier than the G-protein signaling pathway [7], and other times exhibiting a delayed and/or more prolonged signal [8]. Consistent with these distinct signaling pathway characteristics, we and others have shown that β2AR and PAR2 mediate bronchorelaxation through G protein-dependent signaling [4,9,10] and have accumulated evidence suggesting that β-arrestin-dependent signaling downstream of these receptors leads to a pro-inflammatory effect (Fig. 1) [4,11,12]. Because bronchorelaxation and inflammation are mediated via two independent signaling pathways, there is therapeutic potential in developing “biased” or “pathway-specific” ligands that preferentially activate or inhibit one signaling pathway over the other. Substantial murine and initial human data suggest that preferential activation of G-dependent, and inhibition of β-arrestin-dependent, signaling downstream of β2AR or PAR2 receptors would promote desirable effects for asthmatics such as bronchodilation while reducing associated pro-inflammatory effects (reviewed in [3]). This review examines how the dual signaling pathways activated by ligand binding at the β2AR and PAR2 give rise to both beneficial and detrimental effects in asthma and highlights β-arrestin-dependent signaling as the link underlying the parallels between the two.

Figure 1. Dual signaling pathways and paradoxical response to bronchodilators.

Activation of β2AR or PAR2 leads to both β-arrestin-dependent and G protein-dependent signaling. Activation of the G protein-dependent pathway leads to bronchorelaxation whereas activation of the β-arrestin-2-dependent signaling pathway is pro-asthmatic. (β2AR, beta-2-adrenergic receptor; PAR2, protease-activated-receptor-2; ASM, airway smooth muscle.

β-arrestins

β-arrestins are adaptor proteins that are recruited to GPCRs to promote receptor desensitization and internalization, but they can also promote G-protein-independent signals, leading to a diverse array of physiological responses [5,6]. The role for β-arrestins in G protein-dependent signal termination occurs on several levels. The first characterized role for β-arrestins was the uncoupling of GPCRs from their cognate heterotrimeric Gα subunit, leading to a decrease in the responsiveness of the receptor to further agonist stimulation. β-arrestins can also link receptors to clathrin-coated pits, facilitating their internalization. Finally, ubiquitination, and thus, degradation of internalized receptors is facilitated by β-arrestins. In this fashion, β-arrestins are thought to “arrest” the initial G-protein-triggered signal [13]. Over the last decade, a more extensive role for β-arrestins in GPCR signaling has become appreciated. β-arrestins can serve as scaffolds for signaling complexes that then promote G-protein-independent signals. Most of these signals are positive, in that they facilitate activation of the proteins they scaffold, but there are also examples of β-arrestin-dependent inhibition of the enzymatic activity of kinases and GTPases [7,14,15]. A common result of β-arrestin-dependent signaling is cell migration and actin reorganization, as well as transcription of specific genes not targeted by the G-protein pathway [13,16–18]. In some cases, these targets of β-arrestin-dependent inhibition are downstream of G-protein signaling pathways, providing yet another mechanism by which β-arrestins can turn off the G-protein signal. Both the desensitization and signaling roles for β-arrestins come into play in physiological and pathological situations such as regulation of airway responsiveness and airway inflammation. While loss of β-arrestin-induced desensitization can result in uncontrolled G-protein signaling events, which can be pathological, other G-protein signaling events are protective and in the absence of β-arrestins, these protective pathways are enhanced. Furthermore, β-arrestins can promote inflammatory signals; thus in the absence of β-arrestin signaling downstream of a number of GPCRs, inflammation is abated [4,12,19]. This review focuses on two such receptors: β2AR and PAR2, highlighting recent studies that demonstrate the potential therapeutic advantage of developing biased agonists or antagonists that target these receptors.

β2AR and PAR2 signaling in asthma

Dual roles for β-arrestin and G protein signaling in mediating β2AR effects in asthma

β2ARs are ubiquitously expressed and modulate a wide range of cellular responses when activated by epinephrine, their only endogenous ligand [20]. In the airway smooth muscle (ASM) agonist-activated β2ARs couple to Gαs resulting in stimulation of membrane bound adenylyl cyclase, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) generation and activation of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), which mediates relaxation through phosphorylation of cross-bridge cycling regulatory proteins. In addition to the Gαs/cAMP second messenger system, β2ARs also mediate cellular responses via Gαi – induced generation of cGMP and Ca2+; however, cAMP/PKA is the predominant mechanism underlying ASM relaxation (for a more complete review see [21] and Pera and Penn this issue). Through activation of β2AR coupling to Gas, beta-agonists oppose airway smooth muscle (ASM) constriction and inhibit the release of pro-contractile agents, chiefly vagally-released acetylcholine (reviewed in [21,22]). We have shown using multiple methods (in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo) that β-arrestin-2 constrains β2AR-mediated G protein-dependent ASM relaxation [9] making β-arrestin-2 inhibition an attractive therapeutic strategy in asthma irrespective of its pro-inflammatory role.

Shenoy et al. were the first to show that β2ARs can utilize a G-protein-independent, β-arrestin-dependent signaling pathway to exert physiological effects [23]. Since then, several pieces of evidence, when taken together, suggest that β2AR-mediated β-arrestin-dependent signaling is pro-inflammatory in asthma. Firstly, β-arrestins have been implicated as regulators of inflammation in a variety of diseases including asthma, sepsis, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, multiple sclerosis and atherosclerosis [24,25]. Lung β-arrestin expression is up-regulated in murine models of asthma [10] and is similarly dynamically regulated in other inflammatory diseases [24]. Results from multiple murine studies have shown that the asthma phenotype is strikingly diminished in β-arrestin-2−/− mice irrespective of the method of induction of allergic airway disease [4,12,19]. Although development of the asthma phenotype is likely mediated by multiple GPCRs that signal through the β-arrestin-dependent pathway, β2ARs are distinguished as being extremely important. Results from murine studies have shown that the asthma phenotype is significantly suppressed when either β2AR expression or epinephrine synthesis is genetically abrogated [26,27]. Furthermore, blockade of β2AR with select β2AR antagonists (nadolol) can significantly diminish asthma severity in murine models [26,28] and reduce airway sensitivity to methacholine in human trials [29]. Finally, chronic dosing with β-agonists can restore the asthma phenotype in mice that lack epinephrine or exacerbate it in mice that are replete with epinephrine [10,27,30] strongly suggesting that the deleterious effects associated with chronic β2AR agonism in asthma result from β-arrestin-2-dependent signaling.

Like β2ARs, β-arrestin proteins are also widely expressed. Thus, presently it is unknown in which cell type(s) β2AR-mediated β-arrestin-dependent signaling contributes to the development of asthma. Recent evidence points to airway epithelial cells as playing a key role [31]. Airway epithelial expression of membrane-bound β2AR and cytosolic β-arrestin-2 is significantly elevated relative to that in ASM cells [9,10] or T lymphocytes (unpublished data), two additional cell types that also figure prominently in asthma pathogenesis, and the magnitude of impairment of the mucin phenotype in β2AR−/− mice is noticeably greater than that of the inflammatory cell or AHR phenotypes [11]. However, data from β-arrestin-2−/− bone marrow transplant chimeric mice suggest that βarr-mediated signal transduction in hematopoietic cells, in addition to that in lung structural cells, is required for full development of the asthma phenotype [19]. Consistent with this notion, both PAR2- and C-C chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4)-mediated inflammatory cell chemotaxis is β-arrestin-dependent [4,12] in murine asthma models.

Dual roles for β-arrestin and G-protein signaling in mediating PAR2 effects in asthma

PAR2 is widely expressed on inflammatory cells, airway epithelium, smooth muscle and vascular endothelium, where it is activated by serine proteases that cleave the extracellular N-terminus to unveil a tethered ligand (human: SLIGKV/mouse: SLIGRL)[32,33]. This tethered ligand then binds to and activates the receptor, triggering downstream signaling events. Recently, high-affinity and stable agonists, such as 2-furoyl-LIGRL-O (aka 2fAP), have been developed and used both in vivo and in vitro to activate PAR2 [34–36]. Although PAR2 has been implicated in a number of inflammatory disorders, and has been heavily investigated as a putative therapeutic target for asthma, the nature of its involvement remains highly controversial. In favor of a protective role for PAR2 in the airway, PAR2−/− mice demonstrate heightened bronchial smooth muscle cell contraction and airway constriction, and administration of a PAR2 peptide agonist promotes smooth muscle relaxation in isolated bronchioles and abrogates LPS-mediated inflammation [32,37,38]. In contrast, in an OVA-induced model of airway inflammation, cytokine production and infiltration of leukocytes into the bronchioles is impaired in PAR2−/− mice, suggesting a pro-inflammatory role for PAR2 [39–42], and intranasal administration of SLIGRL or 2fAP exacerbates these effects [4,43,44].

Recent studies have provided a plausible answer to this conundrum of the PAR2 role in asthma. First, cytoskeletal reorganization and chemotaxis, which are the main cellular processes underlying the pro-inflammatory effects of PAR2, do not require Gαq/Ca2+ signaling, but rather utilize β-arrestins [7,14,45,46]. β-arrestins can signal to various actin assembly pathways to promote chemotaxis, but a major player in PAR2/β-arrestin signaling is the actin filament severing protein, cofilin [7,47]. Conversely, other studies have demonstrated that PAR2-induced smooth muscle relaxation, which initiates the protective effects in the airway, is mediated by prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), derived from epithelial cells. PGE2 production requires Gαq-induced mobilization of intracellular Ca2+, activation of PI3K and phosphorylation of Akt (which leads to release of PGE2), and nuclear ERK1/2 activation (which leads to expression of cyclooxygenase-1 and -2) [37,48]. Solidifying the importance of the PAR2/β-arrestin signaling axis to inflammation in a modified mouse OVA-induced asthma model are the observations that PAR2-induced recruitment of leukocytes to the airways, mucus production and cytokine release are abolished in β-arrestin-2−/− mice, while PGE2 release and smooth muscle relaxation remain intact [4]. These studies suggest that two different signaling pathways may account for the contrasting effects of PAR2: β-arrestin-dependent leukocyte chemotaxis and Gαq-dependent PGE2 production.

Just as β2ARs are ubiquitously expressed, so too is PAR2, being found in the airway epithelium as well as the invading leukocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes and macrophages) [37,49–51]. The protective effects of PAR2 have been shown to be epithelium-dependent, as PGE2 production and smooth muscle relaxation in bronchiolar rings in response to PAR2 agonists is abolished when the epithelial cells are removed [48,51]. PAR2-induced inflammation in mice is significantly reduced when wild type mice are transplanted with PAR2−/− bone marrow, suggesting a crucial role for PAR2 expressed on the infiltrating leukocytes [4]. However, PAR2−/− mice transplanted with wild type bone marrow also showed reduced leukocyte infiltration, pointing to a role of epithelial PAR2 in the progression of inflammation as well as the protective PGE2 release. Together these data suggest that β-arrestins expressed within the structural and epithelial cells of the lungs, as well as invading leukocytes, contribute to the inflammatory responses during asthma.

Therapeutic Opportunities

Therapeutic targeting of GPCRs has, until very recently, been focused entirely on modulation of responses thought to be mediated by G protein-dependent signaling pathways. With the discovery that GPCRs also utilize β-arrestin-dependent signaling to cause physiological (and pathophysiological) effects, comes the opportunity to therapeutically regulate a second signaling pathway. Specifically, the now established concept of dual independent GPCR signaling pathways allows us to consider the possibility that one signaling pathway can be selectively manipulated to promote events that are therapeutic and avoid, or even inhibit, those that are harmful. For example, the superior clinical efficacy of carvedilol over other β-blockers, which inhibit classic G protein adrenoceptor signaling, in treating heart failure is attributed to carvedilol’s activation of the β-arrestin-dependent signaling pathway [52]. Whereas β–arrestin-dependent signaling is beneficial in heart failure, it appears deleterious in several other diseases (cancer, atherosclerosis, chronic inflammation) including asthma. Substantial murine, and initial human, data suggest that asthma treatment would be significantly improved by preferential activation of β2AR- and PAR2–mediated G protein-dependent bronchodilation and/or inhibition of β-arrestin-dependent pro-inflammatory signaling.

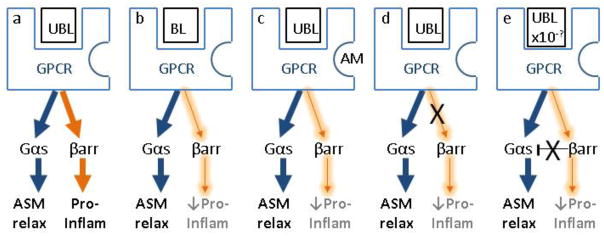

Appreciation for the impact of β-arrestin-dependent signaling on drug discovery is rapidly emerging in the quest for biased ligands, allosteric receptor modulators and β-arrestin inhibitor compounds. Recently developed cell based assays demonstrate that endogenous GPCR ligands are unbiased, in that they activate both the G protein- and β-arrestin-dependent signaling pathways at functionally relevant levels (Fig. 2a). Using these assays, β2AR or PAR2 ligands that favor G signaling over β-arrestin signaling could be found, or designed, and used to treat asthma (Fig. 2b). As an alternative approach, the signaling effects of an unbiased ligand could be shifted to favor Gs-dependent signaling over β-arrestin-dependent signaling by addition of a second drug that, through allosteric modulation, moves the receptor into a biased signaling conformation (Fig. 2c) (see Thanawala this issue). Along the same lines, an unbiased ligand could give rise to G protein-biased signaling if β-arrestin was pharmacologically prevented from participating in signal transduction (Fig. 2d). Yet another angle by which unbiased ligand-induced G protein-dependent signaling might be favored over that mediated by β-arrestin is to develop a drug that inhibits β-arrestin-mediated constraint of G protein-dependent bronchorelaxation (Fig. 2e). Such a drug may allow a normal bronchodilation effect to be generated by a much lower dose of β-agonist/PAR2-agonist which in turn would only weakly activate the pro-inflammatory β-arrestin-dependent signaling pathway.

Figure 2. Impact of β-arrestin-dependent signaling on drug discovery for asthma treatment.

a) Unbiased GPCR ligand functionally activates both the G protein- and Barrestin-dependent signaling pathways leading to bronchorelaxation and inflammation, respectively; b) Biased ligand favors G signaling over β-arrestin signaling; c) Allosteric modulation of the receptor facilitates biased signaling even though the ligand is unbiased; d) Intracellular inhibition of β-arrestin-dependent signaling; e) Low dose unbiased agonist results in normal ASM relaxation due to intracellular inhibition of β-arrestin-mediated constraint of G protein signaling. UBL, unbiased ligand; BL, biased ligand; AM, allosteric modulator; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor, ASM relax, airway smooth muscle relaxation; Pro-inflam, pro-inflammatory; βarr, β-arrestin.

Concluding remarks

Unbiased agonists acting at either β2AR or PAR2 elicit paradoxical responses in asthma. Evidence suggests that ligand-induced protective bronchodilation and deleterious pro-inflammation are mediated through separate G protein- and β-arrestin-dependent signaling pathways, respectively. Selective promotion of the protective signaling pathway or inhibition of the inflammatory one, will lead to therapeutic advances in the treatment of asthma.

Highlights.

β2AR or PAR2 activation is both protective and pro-inflammatory in asthma

β2AR and PAR2 G protein-dependent signaling is protective in asthma

β2AR and PAR2 β-arrestin-dependent signaling is pro-inflammatory in asthma

Biased activation of PAR2 and β2AR G protein signaling may improve asthma treatment.

Biased inhibition of PAR2 and β2AR β-arrestin signaling may improve asthma treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants 1R21HL092388 (to K.A.D.) and R01HL084123 and R01HL093103 (to J.K.L.W.).

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended readings

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Walker JKL, Kraft M, Fisher JT. Assessment of murine lung mechanics outcome measures: alignment with those made in asthmatics. Frontiers in Physiology. 2013;3 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(NAEPP) NAEaPP: Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma–Summary Report 2007. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2007;120:S94–S138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker JKL, Penn RB, Hanania NA, Dickey BF, Bond RA. New perspectives regarding β2-adrenoceptor ligands in the treatment of asthma. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2011;163:18–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4••.Nichols HL, Saffeddine M, Theriot BS, Hegde A, Polley D, El-Mays T, Vliagoftis H, Hollenberg MD, Wilson EH, Walker JKL, et al. β-Arrestin-2 mediates the proinflammatory effects of proteinase-activated receptor-2 in the airway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:16660–16665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208881109. This study demonstrates that unbiased PAR2 ligands mediate protective bronchorelaxation and deleterious inflammation via the G protein-dependent and β-arrestin-dependent signaling pathways, respectively, in an antigen-driven murine asthma model. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lefkowitz RJ, Whalen EJ. [beta]-arrestins: traffic cops of cell signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lefkowitz RJ, Rajagopal K, Whalen EJ. New Roles for β-Arrestins in Cell Signaling: Not Just for Seven-Transmembrane Receptors. Molecular Cell. 2006;24 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zoudilova M, Kumar P, Ge L, Wang P, Bokoch GM, DeFea KA. Beta-arrestin-dependent regulation of the cofilin pathway downstream of protease-activated receptor-2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20634–20646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahn S, Shenoy SK, Wei H, Lefkowitz RJ. Differential kinetic and spatial patterns of beta-arrestin and G protein-mediated ERK activation by the angiotensin II receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35518–35525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9••.Deshpande DA, Theriot BS, Penn RB, Walker JK. Beta-arrestins specifically constrain beta2-adrenergic receptor signaling and function in airway smooth muscle. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2008;22:2134–2141. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-102459. This study shows that β-arrestin significantly constrains β2AR-mediated bronchorelaxation by interrupting G protein-dependent signaling, making β-arrestin an attractive therapeutic target for the treatment of asthma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin R, Degan S, Theriot BS, Fischer BM, Strachan RT, Liang J, Pierce RA, Sunday ME, Noble PW, Kraft M, et al. Chronic treatment in vivo with β-adrenoceptor agonists induces dysfunction of airway β2-adrenoceptors and exacerbates lung inflammation in mice. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2012;165:2365–2377. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Callaerts-Vegh Z, Evans KLJ, Dudekula N, Cuba D, Knoll BJ, Callaerts PFK, Giles H, Shardonofsky FR, Bond RA. Effects of acute and chronic administration of β-adrenoceptor ligands on airway function in a murine model of asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4948–4953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400452101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12•.Walker JK, Fong AM, Lawson BL, Savov JD, Patel DD, Schwartz DA, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta-arrestin-2 regulates the development of allergic asthma. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2003;112:566–574. doi: 10.1172/JCI17265. This study shows that β-arrestin-2 expression is crucial to the development of inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in an antigen-driven murine asthma model. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane receptor signaling through beta-arrestin. Science’s STKE: signal transduction knowledge environment. 2005;2005:cm10. doi: 10.1126/stke.2005/308/cm10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang P, Jiang Y, Wang Y, Shyy JY, DeFea KA. Beta-arrestin inhibits CAMKKbeta-dependent AMPK activation downstream of protease-activated-receptor-2. BMC Biochem. 2010;11:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-11-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang P, Kumar P, Wang C, Defea KA. Differential regulation of class IA phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalytic subunits p110 alpha and beta by protease-activated receptor 2 and beta-arrestins. Biochem J. 2007;408:221–230. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeWire SM, Ahn S, Lefkowitz RJ, Shenoy SK. Beta-arrestins and cell signaling. Annual Review of Physiology. 2007;69:483–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.022405.154749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Defea K. Beta-arrestins and heterotrimeric G-proteins: collaborators and competitors in signal transduction. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153 (Suppl 1):S298–309. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luttrell LM, Gesty-Palmer D. Beyond desensitization: physiological relevance of arrestin-dependent signaling. Pharmacological reviews. 2010;62:305–330. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.002436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hollingsworth JW, Theriot BS, Li Z, Lawson BL, Sunday M, Schwartz DA, Walker JK. Both hematopoietic-derived and non-hematopoietic-derived {beta}-arrestin-2 regulates murine allergic airway disease. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2010;43:269–275. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0198OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lands AM, Arnold A, McAuliff JP, Luduena FP, Brown TG., Jr Differentiation of receptor systems activated by sympathomimetc amines. Nature. 1967;214:597–598. doi: 10.1038/214597a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Penn R, Bond R, Walker JL. GPCRs and Arrestins in Airways: Implications for Asthma. In: Gurevich VV, editor. Arrestins - Pharmacology and Therapeutic Potential. Vol. 219. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: 2014. pp. 387–403. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Billington C, Penn R. Signaling and regulation of G protein-coupled receptors in airway smooth muscle. Respir Res. 2003;4:2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shenoy SK, Drake MT, Nelson CD, Houtz DA, Xiao K, Madabushi S, Reiter E, Premont RT, Lichtarge O, Lefkowitz RJ. beta-arrestin-dependent, G protein-independent ERK1/2 activation by the beta2 adrenergic receptor. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:1261–1273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506576200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan H. β-Arrestins 1 and 2 are critical regulators of inflammation. Innate Immunity. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1753425913501098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vroon A, Heijnen CJ, Kavelaars A. GRKs and arrestins: regulators of migration and inflammation. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2006;80:1214–1221. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0606373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26•.Nguyen LP, Lin R, Parra S, Omoluabi O, Hanania NA, Tuvim MJ, Knoll BJ, Dickey BF, Bond RA. β2-Adrenoceptor signaling is required for the development of an asthma phenotype in a murine model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2435–2440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810902106. This study shows that β2-adrenoceptor null mice are resistant to developing airway hyperresponsiveness, mucous metaplasia, and inflammatory cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, compared to wild type mice in an antigen-driven murine asthma model. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thanawala VJ, Forkuo GS, Al-Sawalha N, Azzegagh Z, Nguyen LP, Eriksen JL, Tuvim MJ, Lowder TW, Dickey BF, Knoll BJ, et al. β2-adrenoceptor Agonists are Required for Development of the Asthma Phenotype in a Murine Model. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2013 doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0364OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen LP, Omoluabi O, Parra S, Frieske JM, Clement C, Ammar-Aouchiche Z, Ho SB, Ehre C, Kesimer M, Knoll BJ, et al. Chronic exposure to beta-blockers attenuates inflammation and mucin content in a murine asthma model. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2008;38:256–262. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0279RC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanania NA, Singh S, El-Wali R, Flashner M, Franklin AE, Garner WJ, Dickey BF, Parra S, Ruoss S, Shardonofsky F, et al. The safety and effects of the β-blocker, nadolol, in mild asthma: an open-label pilot study. Pulm Pharmacol Therapeut. 2008;21:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riesenfeld E, Sullivan M, Thompson-Figueroa J, Haverkamp H, Lundblad L, Bates J, Irvin C. Inhaled salmeterol and/or fluticasone alters structure/function in a murine model of allergic airways disease. Respir Res. 2010;11:22. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dickey BF, Walker JK, Hanania NA, Bond RA. beta-Adrenoceptor inverse agonists in asthma. Current opinion in pharmacology. 2010;10:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cocks TM, Moffatt JD. Protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR2) in the airways. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2001;14:183–191. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2001.0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramachandran R, Noorbakhsh F, Defea K, Hollenberg MD. Targeting proteinase-activated receptors: therapeutic potential and challenges. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2012;11:69–86. doi: 10.1038/nrd3615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGuire JJ, Saifeddine M, Triggle CR, Sun K, Hollenberg MD. 2-furoyl-LIGRLO-amide: a potent and selective proteinase-activated receptor 2 agonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:1124–1131. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.064584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boitano S, Flynn AN, Schulz SM, Hoffman J, Price TJ, Vagner J. Potent agonists of the protease activated receptor 2 (PAR2) Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2011;54:1308–1313. doi: 10.1021/jm1013049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flynn AN, Hoffman J, Tillu DV, Sherwood CL, Zhang Z, Patek R, Asiedu MN, Vagner J, Price TJ, Boitano S. Development of highly potent protease-activated receptor 2 agonists via synthetic lipid tethering. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2013;27:1498–1510. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-217323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cocks TM, Fong B, Chow JM, Anderson GP, Frauman AG, Goldie RG, Henry PJ, Carr MJ, Hamilton JR, Moffatt JD. A protective role for protease-activated receptors in the airways. Nature. 1999;398:156–160. doi: 10.1038/18223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moffatt JD, Jeffrey KL, Cocks TM. Protease-Activated Receptor-2 Activating Peptide SLIGRL Inhibits Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Recruitment of Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes into the Airways of Mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:680–684. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.6.4693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gatti R, Andre E, Amadesi S, Dinh TQ, Fischer A, Bunnett NW, Harrison S, Geppetti P, Trevisani M. Protease-activated receptor-2 activation exaggerates TRPV1-mediated cough in guinea pigs. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:506–511. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01558.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmidlin F, Amadesi S, Dabbagh K, Lewis DE, Knott P, Bunnett NW, Gater PR, Geppetti P, Bertrand C, Stevens ME. Protease-activated receptor 2 mediates eosinophil infiltration and hyperreactivity in allergic inflammation of the airway. J Immunol. 2002;169:5315–5321. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidlin F, Amadesi S, Vidil R, Trevisani M, Martinet N, Caughey G, Tognetto M, Cavallesco G, Mapp C, Geppetti P, et al. Expression and function of proteinase-activated receptor 2 in human bronchial smooth muscle. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1276–1281. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.7.2101157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takizawa T, Tamiya M, Hara T, Matsumoto J, Saito N, Kanke T, Kawagoe J, Hattori Y. Abrogation of bronchial eosinophilic inflammation and attenuated eotaxin content in protease-activated receptor 2-deficient mice. J Pharmacol Sci. 2005;98:99–102. doi: 10.1254/jphs.scz050138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ebeling C, Lam T, Gordon JR, Hollenberg MD, Vliagoftis H. Proteinase-activated receptor-2 promotes allergic sensitization to an inhaled antigen through a TNF-mediated pathway. J Immunol. 2007;179:2910–2917. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.2910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ebeling C, Forsythe P, Ng J, Gordon JR, Hollenberg M, Vliagoftis H. Proteinase-activated receptor 2 activation in the airways enhances antigen-mediated airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness through different pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:623–630. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ge L, Ly Y, Hollenberg M, DeFea K. A beta-arrestin-dependent scaffold is associated with prolonged MAPK activation in pseudopodia during protease-activated receptor-2-induced chemotaxis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34418–34426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang P, DeFea KA. Protease-activated receptor-2 simultaneously directs beta-arrestin-1-dependent inhibition and Galphaq-dependent activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9374–9385. doi: 10.1021/bi0602617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DeFea KA. Stop that cell! Beta-arrestin-dependent chemotaxis: a tale of localized actin assembly and receptor desensitization. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:535–560. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.022405.154804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nagataki M, Moriyuki K, Sekiguchi F, Kawabata A. Evidence that PAR2-triggered prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) formation involves the ERK-cytosolic phospholipase A2-COX-1-microsomal PGE synthase-1 cascade in human lung epithelial cells. Cell Biochem Funct. 2008;26:279–282. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shpacovitch V, Feld M, Bunnett NW, Steinhoff M. Protease-activated receptors: novel PARtners in innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:541–550. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bunnett NW. Protease-activated receptors: how proteases signal to cells to cause inflammation and pain. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2006;32 (Suppl 1):39–48. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-939553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawabata A, Kubo S, Ishiki T, Kawao N, Sekiguchi F, Kuroda R, Hollenberg MD, Kanke T, Saito N. Proteinase-activated receptor-2-mediated relaxation in mouse tracheal and bronchial smooth muscle: signal transduction mechanisms and distinct agonist sensitivity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:402–410. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.068387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wisler JW, DeWire SM, Whalen EJ, Violin JD, Drake MT, Ahn S, Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. A unique mechanism of β-blocker action: Carvedilol stimulates β-arrestin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16657–16662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707936104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]