This review examines the physiological and molecular bone marrow abnormalities associated with diabetes and discusses how bone marrow dysfunction represents a potential root for the development of the multiorgan failure characteristic of advanced diabetes. The notion of diabetes as a bone marrow and stem cell disease opens new avenues for therapeutic interventions ultimately aimed at improving the outcome of diabetic patients.

Keywords: Complications, Stem cells, Regeneration

Abstract

Diabetes mellitus is a global health problem that results in multiorgan complications leading to high morbidity and mortality. Until recently, the effects of diabetes and hyperglycemia on the bone marrow microenvironment—a site where multiple organ systems converge and communicate—have been underappreciated. However, several new studies in mice, rats, and humans reveal that diabetes leads to multiple bone marrow microenvironmental defects, such as small vessel disease (microangiopathy), nerve terminal pauperization (neuropathy), and impaired stem cell mobilization (mobilopathy). The discovery that diabetes involves bone marrow-derived progenitors implicated in maintaining cardiovascular homeostasis has been proposed as a bridging mechanism between micro- and macroangiopathy in distant organs. Herein, we review the physiological and molecular bone marrow abnormalities associated with diabetes and discuss how bone marrow dysfunction represents a potential root for the development of the multiorgan failure characteristic of advanced diabetes. The notion of diabetes as a bone marrow and stem cell disease opens new avenues for therapeutic interventions ultimately aimed at improving the outcome of diabetic patients.

Introduction

Long-term diabetes leads to severe complications in multiple organs that collectively reduce life expectancy, with cardiovascular diseases being the leading cause of diabetes-related death [1]. The molecular pathogenesis of hyperglycemic damage is similar in various cell types, but the impact on functional and homeostatic cellular responses to stressors differ among tissues [2]. Unlike hyperglycemic damage pathways, repair mechanisms have been relatively overlooked. Experimental models that recapitulate the pathophysiology of diabetes show a significant reduction of circulating bone marrow (BM)-derived stem/progenitor cells (notably, endothelial progenitor cells [EPCs]) [3], and depletion of stem/progenitor cells contributes to the development of chronic complications [4]. Moreover, several clinical studies have shown that BM-derived progenitors are functionally impaired in diabetes [5]. These discoveries provide the conceptual basis of a novel pathogenic model for the development of diabetic complications that envisages shortage of BM-derived regenerative cells as its core. Although the concept behind EPCs has been revisited during the last 5 years, such a hypothesis is still valid [6]. Several new studies in mice, rats, and humans reveal that diabetes leads to multiple BM microenvironmental defects (microangiopathy and neuropathy) and impaired stem cell mobilization (mobilopathy). The discovery that diabetes affects BM-derived progenitors implicated in maintaining cardiovascular homeostasis has been proposed as a bridging mechanism between micro- and macroangiopathy in distant organs. To clarify the features and mechanisms driving BM pathology in diabetes, we first introduce the complex cellular networks that regulate BM function and then explore how these networks are altered by diabetes and impact vascular regeneration.

The Bone Marrow Stem Cell Niche

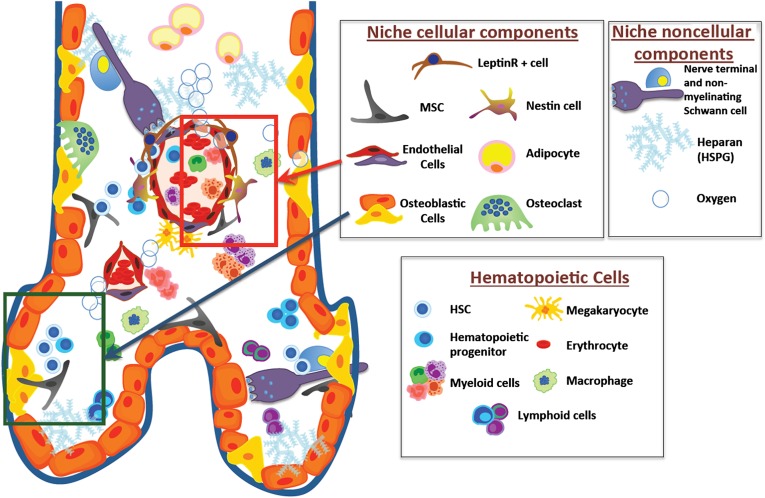

In adulthood, the BM is the major reservoir for hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs), where a specialized microenvironment (niche) hosts and regulates them. Several niche-forming cell types affect HSPC number, fate, and location through an orchestrated network of soluble signals and surface interactions (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The complex cellular and noncellular components of the bone marrow stem cell niche. Green and red boxes highlight the osteoblastic and vascular niches, respectively. Abbreviations: HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; HSPG, heparan sulphate proteoglycan; MSC, mesenchymal stem cells.

The Endosteal Niche

Osteolineage cells lining endosteal surfaces were the first functional niche cells to be discovered. Imaging approaches have demonstrated that transplanted primitive hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) localize closer to the endosteum than more mature progenitors [7]. HSCs at the endosteal location have greater self-renewal capacity than those in the central marrow cavity [8]. Moreover, aged HSCs localize to sites further away from the endosteum compared with young HSCs [9], suggesting that HSC location is affected by aging. Increasing osteoblast number has been shown to expand the HSCs pool [10], whereas deletion of osteoblasts leads to BM HSC depletion [11]. Osteolineage cells secrete large amounts of proteins that affect HSCs, including granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), and express surface molecules that retain HSCs in the niche [12].

Among other cells located at the endosteal region, macrophages have recently received attention as modulators of HSPC mobilization. The mobilizing agent G-CSF reduces osteoblast numbers and inhibits their activity, concomitantly suppressing SDF-1α concentrations, allowing the release of HSPC into the circulation [13]. Macrophages express G-CSF receptor, and G-CSF inhibits osteocalcin and SDF-1α production, leading to osteoblast reduction and HSPC mobilization [14]. Winkler et al. [15] reported that a population of macrophages lining the endosteal region (termed “Osteomacs”) indirectly regulate HSPC retention by modulating the number of osteoblasts. One or more unidentified soluble factors produced by CD169+ macrophages sustain SDF-1α expression by stromal cells, acting against mobilization, whereas macrophage depletion markedly favors spontaneous and G-CSF-induced mobilization [16]. Collectively, these data emphasize the importance of crosstalk between the different components within the endosteal niche.

The Vascular Niche

In addition to the endosteum, HSPCs also localize adjacent to bone marrow sinusoids [7]. The importance of endothelial cells for HSCs traces back to the embryonic life, because HSCs first emerge in the aorta-gonad mesonephric region from a common hemangioblast. Endothelial cells resemble osteoblasts in their ability to nurture HSCs [17]. Ding et al. [18] demonstrated that endothelial cells regulate stem cell factor (SCF) production to retain HSCs in the niche. In addition, vessel microdomains expressing E-selectin are sites of homing for HSC after transplantation [19]. Also, BM endothelial cells undergo extensive changes during conditioning treatments, such as 5′-fluorouracile (5′-FU) administration or irradiation [20]. Interestingly, Winkler et al. [21] reported that the overall number of vessels decreases after G-CSF administration, implying a pivotal role for endothelial cells in mobilization.

Perivascular niche cells in close contact to endothelial cells have also been described as influencing HSPC biology in humans and mice [18, 22]. CD146+ adventitial perisinusoidal cells have bone-forming properties and sustain hematopoiesis [22]. In addition, cells enriched in SDF-1α/CXCL12 (called CAR [CXCL-12 abundant reticular] cells), located close to the vasculature [23], display skeletal stem cell properties and express platelet-derived growth factor receptor, CD44, and vascular cell adhesion molecule. Depletion of perivascular cells leads to HSPC mobilization [24]. Nestin+ cells are enriched in niche and retention genes (Angpt1, Vcam1, Cxcl12, and Scf), have skeletal stem cell properties, and colocalize perivascularly with sympathetic nerve terminal. Nestin+ cells express the β3-adrenergic receptor, and following noradrenergic signaling or administration of G-CSF (which ultimately activates BM sympathetic activity), they downregulate retention signals, allowing HSPC mobilization [25].

Neuronal Control

Beyond the interaction and crosstalk of soluble and cellular components within the niches, the nervous system acts as a multiorgan coordinator by integrating signals coming from distant tissues and by orchestrating rapid responses to stressors. HSPCs are physiologically released in a circadian manner dictated by noradrenergic changes in the BM and fluctuating levels of SDF-1α [26]. HSPC mobilization by G-CSF requires sympathetic nervous signals that act on perivascular cells through β3-adrenergic receptors [27]. Nervous system signaling also has direct effects on HSPCs, because human CD34+ cells express β2-adrenergic receptor, and several neurotransmitters act as direct chemoattractants [28]. Hence, the nervous system exerts global control over multiple cellular components of the hematopoietic system.

Histopathology of the Diabetic Bone Marrow

Arterial vessels enter the BM through foramina nutricia and then divide into arterioles, capillaries, and sinusoids that pervade the central and endosteal marrow. The sinusoids, which are made of a fenestrated endothelium with modest pericyte coverage, form a permeable barrier for the passage of HSPCs into the circulation. Ageing and diseases that disrupt this delicate texture lead to barrier dysfunction and niche destabilization. Of note, the marrow is encapsulated within a rigid container, making it particularly sensitive to local changes in osmotic pressure caused by plasma extravasation. In fact, disruption of vascular or endosteal cells results in HSPC depletion and bone marrow failure [29]. Although the status of BM in diabetes has been overlooked for a long time, it has recently been established that diabetes causes small vessel rarefaction together with relocation of HSPCs, according to a critically reduced perfusion gradient across the marrow [30]. An abnormal location secondary to rearrangement of the hypoxic gradient within the BM was also found in side population HSPCs [31]. Furthermore, markers of oxidative stress, DNA damage, and apoptosis are remarkably increased in BM HSPCs of type 1 diabetic (T1D) mice compared with controls [32]. Such findings in preclinical models are being replicated in humans: a reduction in CD34+ HSPCs was shown in BM aspirates of type 2 diabetic (T2D) compared with nondiabetic subjects, mirroring the scarcity of this population in peripheral blood [33]. An extensive investigation of the histopathology and composition of BM from nondiabetic and T2D subjects confirmed that typical features of the diabetic BM consist of microvascular and hematopoietic cell rarefaction and fat deposition, along with increased apoptosis and reduced abundance of CD34+ cells [34]. In addition, BM endothelial cell dysfunction leads to excess vascular permeability [32], another microangiopathic feature typically seen in diabetic retinopathy. Such endothelial barrier alterations favor extravasation of macromolecules and erythrocytes, paving the way to microangiopathy and complex remodeling of the tissue. In view of the wide heterogeneity in the structure and function of organ-specific endothelial cells [35, 36] and of the specific features of the BM microvasculature, it is important to note that such findings were obtained using BM-derived endothelial cells [32]. Unfortunately, BM endothelial cells are technically difficult to isolate, and there is a general paucity of studies conducted using tissue-specific cells.

Because the BM is rich in sympathetic nerve terminals, this can be easily viewed in the framework of the diabetic autonomic neuropathy, which can affect virtually any organ and tissue. Although discrepancies exist in the literature regarding BM nerve fiber endings in models of diabetes [11, 37], we have recently shown that sympathectomy in T1D and T2D mice develops in response to oxidative stress and is responsible for BM dysfunction. In addition, worsening degrees of autonomic neuropathy associate with progressive depletion of CD34+ cells in diabetic patients, confirming the negative impact of sympathectomy on BM function in humans [38].

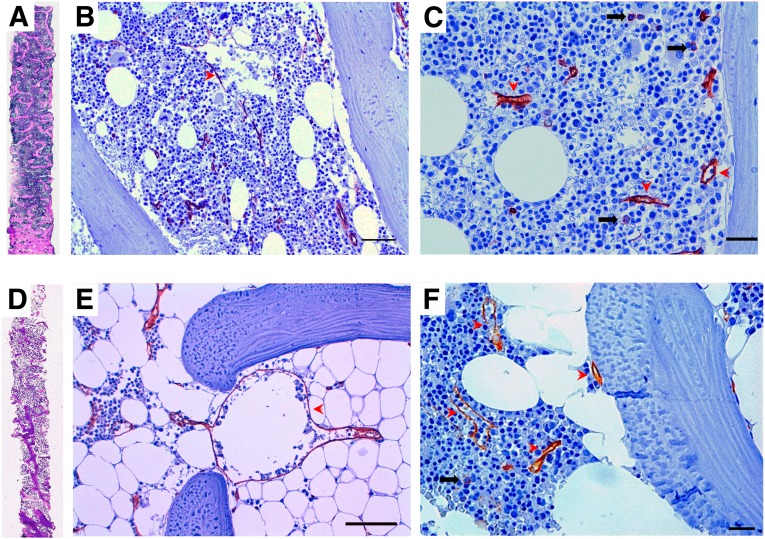

In addition to microangiopathy, neuropathy, and stem cell rarefaction, the diabetic BM is characterized by extensive fatty infiltration (Fig. 2). The reasons for this are unclear, and such excess adipose tissue can be viewed as a feature of accelerated aging or in the framework of ectopic fat accumulation that is typical of T2D, metabolic syndrome, and uncontrolled T1D. Whatever the mechanism, intramarrow fat is recognized as a negative regulator of hematopoiesis [39], suggesting a potential pathogenic role of this alteration.

Figure 2.

Representative histopathologic features of the human diabetic bone marrow. (A, D): The entire biopsies from a control patient (A) and a diabetic (D) patient show reduced trabecular bone and increased marrow fat. (B–F): Immunoperoxidase CD34 (brownish) labeling in sections of human bone marrow (BM) documenting small individual progenitor cells ([C] and [F], black arrows) and the endothelial lining of capillaries and sinusoids (red arrowheads). An abnormally large paratrabecular sinusoid in a diabetic fatty BM is shown in (E), as part of the diabetic BM microangiopathy. Scale bars = 50 µm in (B) and (E) and 20 µm in (C) and (F).

The Diabetic Stem Cell Mobilopathy

The aforementioned histopathological changes impact the ability of the diabetic BM to release HSPCs into the bloodstream. It was first reported in 2006 that T1D rats are unable to mobilize HSPCs after hind limb ischemia. This was attributable to a defective hypoxia-responsive signaling from the muscle to the BM via blunted hypoxia-inducible factor 1α-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)/SDF-1α axis [40]. However, diabetic rats were also less responsive to mobilizing cytokines (G-CSF and SCF) acting directly on the BM, thus suggesting a primary BM defect [40]. In a model of T2D in rats, Busik et al. [37] showed that BM denervation is accompanied by a loss of physiological circadian release of EPCs. We have also recently found that BM sympathectomy is responsible for impaired stem cell mobilization elicited by G-CSF or hind limb ischemia in T1D and T2D mice [38]. Based on the above discussed role of the sympathetic nervous system in regulating HSPC trafficking, it is easy to understand how diabetes-induced neuropathy is a crucial contributing factor to the observed BM dysfunction.

Ischemia- and G-CSF-induced mobilization in T1D rats is also at least in part attributed to a tissue-specific alteration in DPP-4 activity that regulates the local and systemic concentrations of SDF-1α [33]. DPP-4 is believed to exert a key role in the regulation of stem cell mobilization and vascular repair in diabetes [41]. Impaired response to G-CSF-induced mobilization of HSPC in T1D and T2D models has been confirmed in mice [11]. Such study was prompted by a retrospective case series of patients undergoing autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation, showing that diabetes and hyperglycemia were predictors of a poor mobilizer phenotype [11]. This finding in humans has been strongly substantiated by a prospective clinical trial in which diabetic and control subjects received a single low-dose G-CSF administration to study stem/progenitor cell mobilization. Compared with controls, T1D and T2D patients showed a striking inability to mobilize CD34+ stem cells and proangiogenic cells after G-CSF [42]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis of clinical trials in which high-dose G-CSF was administered for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases found that diabetes was the strongest negative determinant of stem cell yield [43]. Recently, impairment of ischemia-induced mobilization has been confirmed in T2D patients who exhibited a lower and delayed peak of spontaneous EPC mobilization after acute myocardial infarction, which correlated with a poorer prognosis compared with nondiabetic controls [44]. Taken together, these data strongly indicate that the diabetic BM fails to mobilize stem/progenitor cells after G-CSF and tissue ischemia, a pathological condition now deemed as “mobilopathy” [45]. This mobilopathy cannot be simply attributed to a reduction in the number of intramarrow cells available for mobilization. In animal models of diabetes, the number of BM stem cells was found to be decreased [46], unaffected [43], or even increased [11], according to diabetes model, type, and duration. In humans, BM CD34+ stem cells are reduced [33, 34], but defective mobilization takes place before baseline circulating stem cell levels decline [42].

Mechanisms of Bone Marrow Damage and Dysfunction in Diabetes

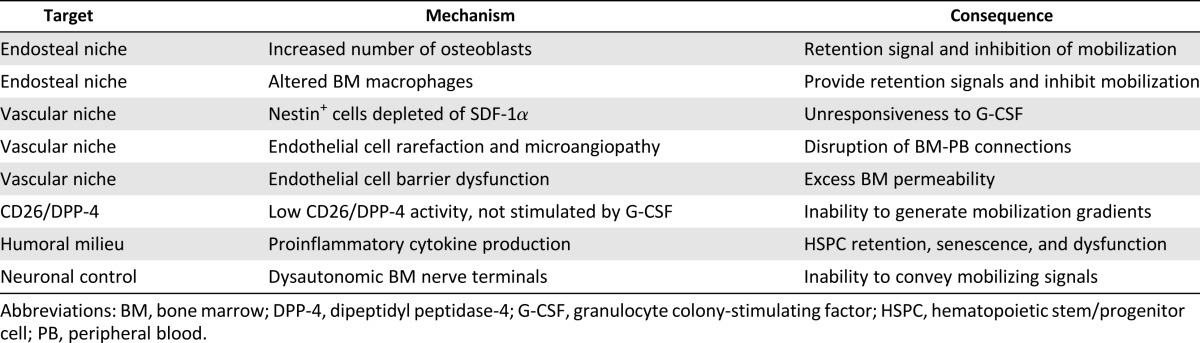

Several potential mechanisms can contribute to the diabetic stem cell mobilopathy (Table 1), because each of the components of the BM stem cell niche shows at least some degree of derangement in models of diabetes. In steady state, T1D mice have reduced numbers of osteoblastic cells, increased plasma SDF-1α concentrations, and increased circulating HSPCs compared with nondiabetic controls. Accordingly, osteoblast depletion in nondiabetic mice increased the number of baseline circulating progenitors and decreased the response to G-CSF administration, partially recapitulating the diabetic phenotype [11]. Furthermore, osteopontin+ cells of the endosteal niche of T1D mice show an impaired ability to support HSPC in vitro and in vivo [47]. These data emphasize the importance of osteoblastic cells in the HSPC retention and mobilization defect in diabetes. How this is related to a general bone remodeling in diabetes is unknown and worthy of investigation.

Table 1.

The mechanisms of BM pathology and dysfunction in diabetes

Perivascular niche cells are also candidate targets of diabetic BM alterations. In diabetic mice, perivascular nestin+ cells are unable to downregulate SDF-1α upon challenge with G-CSF, resulting in deficient mobilization. This is consistent with a study in diabetic rats showing deregulation of the SDF-1α-inactivating enzyme DPP-4 in the BM [33]. Normally, G-CSF stimulates DPP-4, which is required for its mobilizing effect [48], whereas this surge in DPP-4 activity is absent in experimental diabetes and in humans [33, 42].

Given the paracrine role of the BM endothelium in regulating HSPC self-renewal, maintenance, and differentiation [18], a failure of diabetic BM endothelial cells to secrete sufficient amounts of angiocrine factors might contribute to diabetes-induced malfunction of the niche. A study evaluating the impact of diabetes on gene expression profile in BM endothelial cells found that genes involved in cell death, cytoskeleton assembly, organization, trafficking, and inflammation were differentially modulated by diabetes [32]. Functional analyses identified small GTPases, actin cytoskeleton dynamics, integrin, leukocyte extravasation, and tight junctions as the most affected signaling pathways. RhoA activity was increased in diabetic BM endothelial cells through a redox-dependent mechanism activation, the rho-associated, coiled-coil-containing protein kinase (ROCK)1/ROCK2 and mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathways, and inhibiting of Akt, thus leading to changes in cell migration, network formation, and angiocrine factor release that ultimately result in barrier dysfunction [32]. Collectively, these data provide a molecular basis for the observed alteration of endothelial barrier function in the diabetic BM.

Hazra et al. [31] explored the role of inflammation in the derangement of BM microenvironment in T1D mice. In this study, the authors found that BM supernatant of diabetic mice displayed higher concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines, gp130 ligands, and monocyte/macrophage stimulating factors. Interestingly, gp130−/− mice, which are less responsive to inflammatory cytokines, were protected from BM dysfunction induced by diabetes [31]. Alterations in BM cytokine expression by long-term T1D in mice was also reported by Orlandi et al. [46], who found increased levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 and insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5, osteoprotegerin, and VEGF. Together with reduced expression of the Bmi1 gene, which prevents HSPC senescence, these changes might be responsible for the impaired repopulation capacity of the diabetic BM stem cell niche [46]. Defective repopulation and recovery after challenge with 5′-FU have also been reported by Westerweel et al. [49] in T1D mice. Normally, BM stromal cells and endothelial cells support HSPC clonogenesis. It has been shown that stromal cells from diabetic animals and endothelial cells cultured in high glucose show an impaired capacity to sustain HSPC expansion, again pointing to a dysfunction of the diabetic stem cell niche [49].

Alterations in BM monocyte/macrophage cells may represent another inflammatory drive of HSPC retention versus mobilization in diabetes. T2D affects the BM-to-peripheral blood distribution of M1 (inflammatory) and M2 (anti-inflammatory) monocyte macrophages and the M1/M2 mobilizing effect of G-CSF [50]. The pathway linking hyperglycemia to a disturbed myelogenesis has recently been identified and involves the excess production of receptor for advanced glycation end-products ligands by neutrophils [51]. Changes in BM myeloid cells can thus contribute to the diabetic stem cell mobilopathy [16]. In the inflammatory milieu, stem and progenitor cell trafficking is regulated by prostaglandins and can be modulated by prostaglandin synthesis inhibition by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [52]. Whether this is a suitable therapeutic strategy in diabetes is worth investigating.

Finally, diabetes and high glucose affect the expression of master microRNA regulating stem cell homeostasis, expansion, and differentiation, as demonstrated for miR-155 in human CD34+ progenitor cells, whose suppression inhibits cell cycle progression and activation of the p21/p27 pathway [34]. These data are important because they provide initial insight into the molecular mechanisms driving BM stem cell dysfunction in human diabetes.

Consequences and Therapeutic Implications of BM Dysfunction on Vascular Regeneration

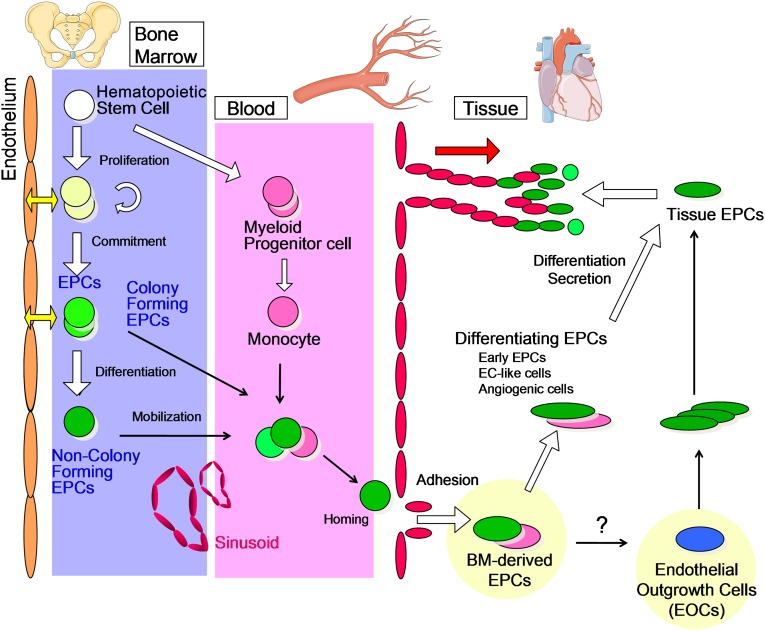

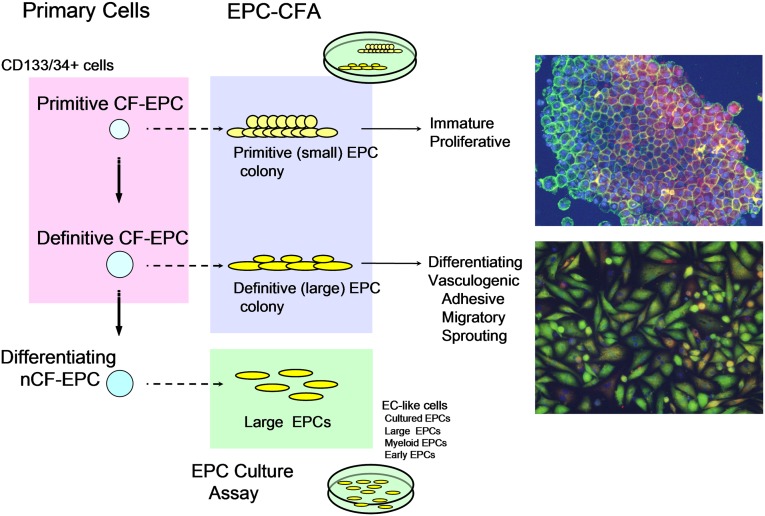

In addition to HSPCs, the BM harbors multiple tissue-committed progenitor cells involved in vascular homeostasis and implicated in diabetic complications, such as EPCs [4]. EPCs migrate from the BM to foci of neovascularisation [53]. They are mainly divided into hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic EPCs. Hematopoietic EPCs originate from the BM (Fig. 3) and represent a heterogeneous population including colony-forming EPCs, non-colony-forming “differentiating” EPCs, and myeloid EPCs (or angiogenic cells) [54]. Because experimental evidence shows that HSPCs and endothelial cells are derived from a common precursor (hemangioblast or hemogenic endothelium) [55], it has been speculated that the origin of circulating adult EPCs could be related to HSCs [54]. In this regard, the characterization and identification of EPCs are tightly linked to methods and markers applied for HSPC [56]. Although beyond the scope of this perspective article, it is worth mentioning that a unique combination of specific and selective markers enabling an unambiguous distinction between EPCs and HSPCs is still missing [54]. Rather, a novel EPC colony-forming assay (EPC-CFA) has been developed to allow a hierarchic view on circulating EPCs [57]. The EPC-CFA of progenitor-enriched populations identifies two kinds of single cell-derived colonies: small-EPC colony and large-EPC colony. Based on their in vitro and in vivo characteristics, small-EPCs represent “primitive EPCs,” a highly immature and proliferative population of cells, whereas large-EPCs represent “definitive EPCs,” cells prone to differentiate and promote vasculogenesis (Fig. 4). In contrast, non-colony-forming EPCs, such as adhesive endothelial-like cells derived from peripheral blood or BM mononuclear cells, represent further differentiating EPC phenotypes [54]. In addition, mature hematopoietic cells, namely myelomonocytic cells, have also been demonstrated to contribute to peripheral endothelium [58]. Myeloid lineage cells may therefore function as differentiating EPCs, giving rise to endothelial-like cells and contributing to neovascularization in ischemia or tissue damage (Fig. 3). Beyond the possibility that myeloid EPCs differentiate into endothelial cells, BM-derived inflammatory cells are important players in vascular regeneration. Specifically, monocyte macrophagones are endowed with great plasticity, and they represent essential regulators of tissue remodeling [59]. Although classically activated M1 macrophages promote inflammation and vascular disease, alternatively activated M2 macrophages provide anti-inflammatory signals and are proangiogenic [60]. Interestingly, diabetes reduces M2 cells through a BM-related effect, thereby unbalancing the M1/M2 polarization status [50]. A series of preclinical and clinical data supports a pathophysiological model primarily involving myeloid cells in the crosstalk between the BM and the heart [61]. Furthermore, neutrophils are receiving renewed attention in the pathogenesis of vascular disease, a role carried out through their release of neutrophil extracellular traps [62]. Therefore, the increased myelogenesis associated with diabetes [51] not only represents one of the features of the diabetic BM, but also has important implications for vascular disease. Altogether, these data indicate that the hematopoietic BM is a source of several cell types with different impact on vascular biology.

Figure 3.

Hierarchical organization of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and EPCs. The relationships between BM HSCs and various EPCs and how the latter reach the bloodstream are shown. The figure depicts the interplay between EPC phenotypes in the processes of angiogenesis. Abbreviations: BM, bone marrow; EC, endothelial cell; EOC, endothelial outgrowth cell; EPC, endothelial progenitor cell.

Figure 4.

The EPC CFA used to define the hematopoietic stem cell/EPC hierarchy. Representative immunofluorescent staining of the two colony-forming EPC types is shown. Red color fluorescence indicates acetylated LDL uptake, and green color fluorescence shows isolectin B4 bindings. The double positivity indicates endothelial lineage cells. Abbreviations: CF, colony-forming; CFA, colony-forming assay; EC, endothelial cell; EPC, endothelial progenitor cell; nCF, non-colony-forming assay.

Diabetic vascular diseases are characterized by endothelial dysfunction, remodeling of large and small arteries with tissue hypoperfusion, and hypoxia. Diabetes typically impairs vascularization mechanisms, such as pre-existing collaterals and new blood vessel formation by arteriogenesis and angiogenesis, thereby worsening the recovery from an ischemic insult [63]. Although the classical pathogenic mechanisms that damage endothelial cells and the vasculature in diabetes are well known [2], the interest has recently moved to consider the impairment in reparatory mechanisms and insufficiency of vascular regeneration processes [6, 64]. CD34+ blood cells from T1D patients were found to be reduced compared with healthy controls, and exogenous nondiabetic CD34+ cells accelerated blood flow recovery in a diabetic model of limb ischemia [65]. Tepper et al. [66] demonstrated impairment of human diabetic EPCs in functions critical for neovascularization, such as cell proliferation, adhesion, and tube formation. Ischemia, a well-recognized entity of diabetic wounds, is a major setting of EPC involvement [67], whereas responses to hypoxia, including EPC kinetic regulation, are impaired in diabetes [68]. Indeed, homing of EPCs to sites of delayed wound healing is markedly compromised in T1D mice [69]. Thus, although the pathogenesis of impaired diabetic wound healing is multifactorial, EPC dysregulation is now believed to play a role. In preclinical studies, the administration of exogenous EPCs proved effective as a vasculogenic therapy in myocardial, cerebral, and hind limb ischemia [70]. When applied to the clinic, cell therapies with EPC-enriched products proved to be safe and potentially effective in treating myocardial infarction and peripheral arterial disease [71, 72]. It should be noted that most BM-derived cell products used in clinical trials include a vast proportion of inflammatory cells, which should be themselves implicated in the clinical effect. In a phase III trial of G-CSF-mobilized EPC therapy for nonhealing diabetic ulcers, better results were seen in patients receiving highly vasculogenic EPCs [73], suggesting that the success of EPC therapy can be compromized by intrinsic diabetic EPC dysfunction and mobilopathy. Recently, a serum-free quality and quantity culture system that enhances the vasculogenic potential of EPCs has been shown to reverse the detrimental effects of diabetes on EPC ex vivo [74], a method that might aid a sufficient number of functional EPCs for autologous cell therapy.

Because impaired EPC function and mobilization accounts, at least in part, for the diminished neovascularization in diabetes, therapies aiming to re-educate endogenous BM-derived EPCs may offer novel opportunities to treat chronic diabetic complications by restoring normal neovascularization and vascular repair. Strategies to counteract BM alterations in diabetes therefore have the potential to delay or reverse the progression of other end-organ complications.

So far, a limited number of strategies can be postulated based on the available data. It was initially suggested that lowering blood glucose with insulin partly restores BM responsiveness to ischemia, in terms of progenitor cell mobilization [40]. Because restoration of EPC levels with glucose control in patients requires time [75], it is more likely that this protective effect is indirectly mediated by mitigation of advanced glycation end products and quenching of oxidative stress. In fact, boosting the thiamine-dependent enzyme transketolase by benfothiamine supplementation was able to prevent diabetic BM microangiopathy in mice [30]. Experiments showing that mice with a genetic deletion of the pro-oxidant p66Shc are protected from BM denervation and mobilopathy confirm the prominent role of oxidative stress in inducing BM damage in diabetes [38]. Along the same line, an epigenetic therapy with microRNA-155, which regulates oxidative stress-induced apoptosis, has been proposed to be beneficial against BM niche dysfunction [34]. In addition to microangiopathy, neuropathy is highly likely to affect BM function in diabetes, and therefore, sympathetic nervous system (SNS)-independent (e.g., AMD3100) rather than SNS-dependent (e.g., G-CSF) factors should be used to stimulate the diabetic BM [11, 38]. Similarly, potentiating the residual sympathetic output with norepinephrin reuptake inhibitors might be a valuable strategy to counter BM dysfunction and impaired vascular recovery induced by diabetic neuropathy [38]. Based on the prominent role played by innate immunity in BM niche regulation and on the proinflammatory pathways activated in the diabetic BM [34, 46], it can also be anticipated that anti-inflammatory therapies can have beneficial effects, but no data are so far available in support of this hypothesis.

Finally, clinically available drugs have the ability to affect BM niche regulatory elements through off-target effects, making them candidates for assessing their beneficial effects on the diabetic BM and BM-derived cell-mediated vascular repair. In this regard, DPP-4 inhibition has been shown to restore ischemia-induced mobilization in diabetes, favoring the SDF-1α switch [33, 41].

Conclusion

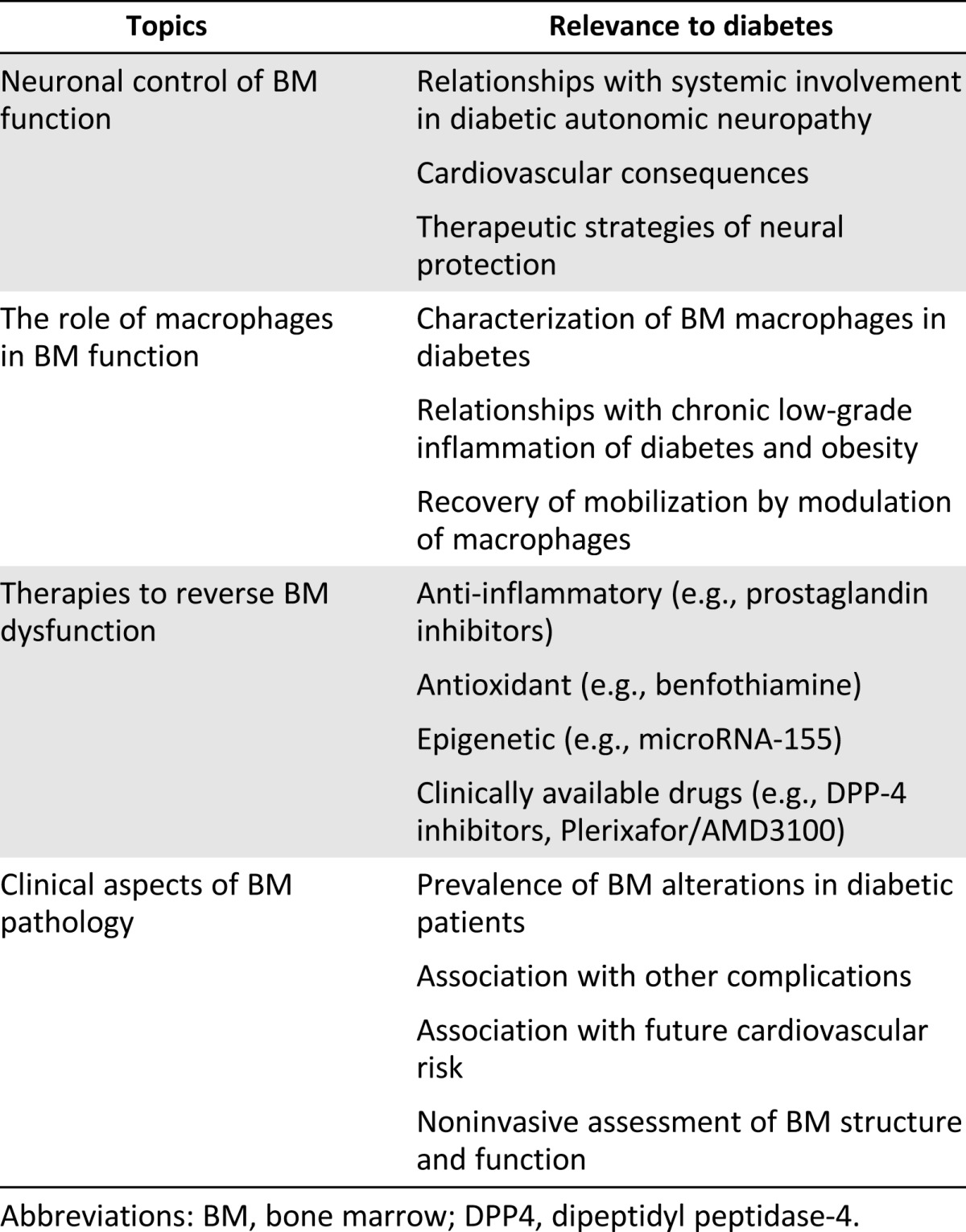

We have presented the current evidence indicating that the BM is a major target of diabetic tissue damage. Diabetes affects BM architecture and function, impairing the mobilization of immature cells into the bloodstream, thus decreasing the pool of circulating cells with regenerative potential. EPCs provide a clue to understand the role of BM-derived cells in the pathophysiology and natural history of diabetes and its vascular complications. By replenishing cells that aid vascular health and repair, the BM normally acts as a central housekeeper that prevents or retards vascular diseases. This previously unrecognized function of the BM is compromised in diabetic patients, mainly because of a broad structural and functional BM remodeling. This field of investigation is in its infancy, and extensive work to detail the mechanisms that govern BM dysfunction in diabetes is needed. We propose a series of topics to be covered and questions to be answered (Table 2). Therapeutic strategies directed to restore BM and boost its endogenous regenerative cells are attractive to delay or potentially reverse diabetic complications.

Table 2.

Topics to be covered by future research on the diabetic BM pathology

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes (EFSD)/Lilly Grant & Fellowship program, a EFSD/Novartis program, and an Italian Ministry of Health grant (GR-2010-2301676) to G.P.F.

Author Contributions

G.P.F., F.Q., F.F., T.A., and P.M.: conception and design, collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Seshasai SR, Kaptoge S, Thompson A, et al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:829–841. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: A unifying mechanism. Diabetes. 2005;54:1615–1625. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, et al. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science. 1997;275:964–967. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fadini GP, Avogaro A.It is all in the blood: The multifaceted contribution of circulating progenitor cells in diabetic complications Exp Diabetes Res 2012;2012:742976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fadini GP. An underlying principle for the study of circulating progenitor cells in diabetes and its complications. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1091–1094. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fadini GP. A reappraisal on the role of circulating (progenitor) cells in the pathobiology of diabetic complications. Diabetologia. 2014;57:4–15. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-3087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lo Celso C, Fleming HE, Wu JW, et al. Live-animal tracking of individual haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in their niche. Nature. 2009;457:92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature07434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haylock DN, Williams B, Johnston HM, et al. Hemopoietic stem cells with higher hemopoietic potential reside at the bone marrow endosteum. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1062–1069. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Köhler A, Schmithorst V, Filippi MD, et al. Altered cellular dynamics and endosteal location of aged early hematopoietic progenitor cells revealed by time-lapse intravital imaging in long bones. Blood. 2009;114:290–298. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arai F, Hirao A, Ohmura M, et al. Tie2/angiopoietin-1 signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence in the bone marrow niche. Cell. 2004;118:149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferraro F, Lymperi S, Mendez-Ferrer S, et al. Diabetes impairs hematopoietic stem cell mobilization by altering niche function Sci Transl Med 2011;3:104ra101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taichman RS, Reilly MJ, Emerson SG. Human osteoblasts support human hematopoietic progenitor cells in vitro bone marrow cultures. Blood. 1996;87:518–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Semerad CL, Christopher MJ, Liu F, et al. G-CSF potently inhibits osteoblast activity and CXCL12 mRNA expression in the bone marrow. Blood. 2005;106:3020–3027. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christopher MJ, Rao M, Liu F, et al. Expression of the G-CSF receptor in monocytic cells is sufficient to mediate hematopoietic progenitor mobilization by G-CSF in mice. J Exp Med. 2011;208:251–260. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winkler IG, Sims NA, Pettit AR, et al. Bone marrow macrophages maintain hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niches and their depletion mobilizes HSCs. Blood. 2010;116:4815–4828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-253534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chow A, Lucas D, Hidalgo A, et al. Bone marrow CD169+ macrophages promote the retention of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in the mesenchymal stem cell niche. J Exp Med. 2011;208:261–271. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li W, Johnson SA, Shelley WC, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell repopulating ability can be maintained in vitro by some primary endothelial cells. Exp Hematol. 2004;32:1226–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding L, Saunders TL, Enikolopov G, et al. Endothelial and perivascular cells maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2012;481:457–462. doi: 10.1038/nature10783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sipkins DA, Wei X, Wu JW, et al. In vivo imaging of specialized bone marrow endothelial microdomains for tumour engraftment. Nature. 2005;435:969–973. doi: 10.1038/nature03703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Narayan K, Juneja S, Garcia C. Effects of 5-fluorouracil or total-body irradiation on murine bone marrow microvasculature. Exp Hematol. 1994;22:142–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winkler IG, Barbier V, Wadley R, et al. Positioning of bone marrow hematopoietic and stromal cells relative to blood flow in vivo: Serially reconstituting hematopoietic stem cells reside in distinct nonperfused niches. Blood. 2010;116:375–385. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-233437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sacchetti P, Sousa KM, Hall AC, et al. Liver X receptors and oxysterols promote ventral midbrain neurogenesis in vivo and in human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:409–419. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Noda M, et al. Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity. 2006;25:977–988. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Omatsu Y, Sugiyama T, Kohara H, et al. The essential functions of adipo-osteogenic progenitors as the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell niche. Immunity. 2010;33:387–399. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Méndez-Ferrer S, Michurina TV, Ferraro F, et al. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466:829–834. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Méndez-Ferrer S, Lucas D, Battista M, et al. Haematopoietic stem cell release is regulated by circadian oscillations. Nature. 2008;452:442–447. doi: 10.1038/nature06685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lucas D, Battista M, Shi PA, et al. Mobilized hematopoietic stem cell yield depends on species-specific circadian timing. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:364–366. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spiegel A, Shivtiel S, Kalinkovich A, et al. Catecholaminergic neurotransmitters regulate migration and repopulation of immature human CD34+ cells through Wnt signaling. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1123–1131. doi: 10.1038/ni1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J, Niu C, Ye L, et al. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature. 2003;425:836–841. doi: 10.1038/nature02041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oikawa A, Siragusa M, Quaini F, et al. Diabetes mellitus induces bone marrow microangiopathy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:498–508. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.200154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hazra S, Jarajapu YP, Stepps V, et al. Long-term type 1 diabetes influences haematopoietic stem cells by reducing vascular repair potential and increasing inflammatory monocyte generation in a murine model. Diabetologia. 2013;56:644–653. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2781-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mangialardi G, Katare R, Oikawa A, et al. Diabetes causes bone marrow endothelial barrier dysfunction by activation of the RhoA-Rho-associated kinase signaling pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:555–564. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fadini GP, Albiero M, Seeger F, et al. Stem cell compartmentalization in diabetes and high cardiovascular risk reveals the role of DPP-4 in diabetic stem cell mobilopathy. Basic Res Cardiol. 2013;108:313. doi: 10.1007/s00395-012-0313-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spinetti G, Cordella D, Fortunato O, et al. Global remodeling of the vascular stem cell niche in bone marrow of diabetic patients: Implication of the microRNA-155/FOXO3a signaling pathway. Circ Res. 2013;112:510–522. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.300598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aird WC. Phenotypic heterogeneity of the endothelium: II. Representative vascular beds. Circ Res. 2007;100:174–190. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000255690.03436.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aird WC. Phenotypic heterogeneity of the endothelium: I. Structure, function, and mechanisms. Circ Res. 2007;100:158–173. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000255691.76142.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Busik JV, Tikhonenko M, Bhatwadekar A, et al. Diabetic retinopathy is associated with bone marrow neuropathy and a depressed peripheral clock. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2897–2906. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Albiero M, Poncina N, Tjwa M, et al. Diabetes causes bone marrow autonomic neuropathy and impairs stem cell mobilization via dysregulated p66Shc and Sirt1. Diabetes. 2014; 63:1353–1365. doi: 10.2337/db13-0894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naveiras O, Nardi V, Wenzel PL, et al. Bone-marrow adipocytes as negative regulators of the haematopoietic microenvironment. Nature. 2009;460:259–263. doi: 10.1038/nature08099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fadini GP, Sartore S, Schiavon M, et al. Diabetes impairs progenitor cell mobilisation after hindlimb ischaemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Diabetologia. 2006;49:3075–3084. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fadini GP, Avogaro A. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibition and vascular repair by mobilization of endogenous stem cells in diabetes and beyond. Atherosclerosis. 2013;229:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fadini GP, Albiero M, Vigili de Kreutzenberg S, et al. Diabetes impairs stem cell and proangiogenic cell mobilization in humans. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:943–949. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fadini GP, Avogaro A. Diabetes impairs mobilization of stem cells for the treatment of cardiovascular disease: A meta-regression analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:892–897. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.10.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ling L, Shen Y, Wang K, et al. Worse clinical outcomes in acute myocardial infarction patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Relevance to impaired endothelial progenitor cells mobilization. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DiPersio JF. Diabetic stem-cell “mobilopathy”. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2536–2538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1112347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Orlandi A, Chavakis E, Seeger F, et al. Long-term diabetes impairs repopulation of hematopoietic progenitor cells and dysregulates the cytokine expression in the bone marrow microenvironment in mice. Basic Res Cardiol. 2010;105:703–712. doi: 10.1007/s00395-010-0109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chiba H, Ataka K, Iba K, et al. Diabetes impairs the interactions between long-term hematopoietic stem cells and osteopontin-positive cells in the endosteal niche of mouse bone marrow. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;305:C693–C703. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00400.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Christopherson KW, 2nd, Cooper S, Broxmeyer HE. Cell surface peptidase CD26/DPPIV mediates G-CSF mobilization of mouse progenitor cells. Blood. 2003;101:4680–4686. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Westerweel PE, Teraa M, Rafii S, et al. Impaired endothelial progenitor cell mobilization and dysfunctional bone marrow stroma in diabetes mellitus. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fadini GP, de Kreutzenberg SV, Boscaro E, et al. An unbalanced monocyte polarisation in peripheral blood and bone marrow of patients with type 2 diabetes has an impact on microangiopathy. Diabetologia. 2013;56:1856–1866. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2918-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagareddy PR, Murphy AJ, Stirzaker RA, et al. Hyperglycemia promotes myelopoiesis and impairs the resolution of atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2013;17:695–708. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoggatt J, Mohammad KS, Singh P, et al. Differential stem- and progenitor-cell trafficking by prostaglandin E2. Nature. 2013;495:365–369. doi: 10.1038/nature11929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Asahara T, Masuda H, Takahashi T, et al. Bone marrow origin of endothelial progenitor cells responsible for postnatal vasculogenesis in physiological and pathological neovascularization. Circ Res. 1999;85:221–228. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fadini GP, Losordo D, Dimmeler S. Critical reevaluation of endothelial progenitor cell phenotypes for therapeutic and diagnostic use. Circ Res. 2012;110:624–637. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dieterlen-Lièvre F, Jaffredo T. Decoding the hemogenic endothelium in mammals. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:189–190. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Timmermans F, Plum J, Yöder MC, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells: Identity defined? J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:87–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Masuda H, Alev C, Akimaru H, et al. Methodological development of a clonogenic assay to determine endothelial progenitor cell potential. Circ Res. 2011;109:20–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.231837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bailey AS, Willenbring H, Jiang S, et al. Myeloid lineage progenitors give rise to vascular endothelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13156–13161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604203103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mantovani A, Garlanda C, Locati M. Macrophage diversity and polarization in atherosclerosis: A question of balance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1419–1423. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.180497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jetten N, Verbruggen S, Gijbels MJ, et al. Anti-inflammatory M2, but not pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages promote angiogenesis in vivo. Angiogenesis. 2014;17:109–118. doi: 10.1007/s10456-013-9381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dutta P, Courties G, Wei Y, et al. Myocardial infarction accelerates atherosclerosis. Nature. 2012;487:325–329. doi: 10.1038/nature11260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Borissoff JI, Joosen IA, Versteylen MO, et al. Elevated levels of circulating DNA and chromatin are independently associated with severe coronary atherosclerosis and a prothrombotic state. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:2032–2040. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abaci A, Oğuzhan A, Kahraman S, et al. Effect of diabetes mellitus on formation of coronary collateral vessels. Circulation. 1999;99:2239–2242. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.17.2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Avogaro A, Albiero M, Menegazzo L, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes: The role of reparatory mechanisms. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(Suppl 2):S285–S290. doi: 10.2337/dc11-s239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schatteman GC, Hanlon HD, Jiao C, et al. Blood-derived angioblasts accelerate blood-flow restoration in diabetic mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:571–578. doi: 10.1172/JCI9087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tepper OM, Galiano RD, Capla JM, et al. Human endothelial progenitor cells from type II diabetics exhibit impaired proliferation, adhesion, and incorporation into vascular structures. Circulation. 2002;106:2781–2786. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000039526.42991.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tepper OM, Capla JM, Galiano RD, et al. Adult vasculogenesis occurs through in situ recruitment, proliferation, and tubulization of circulating bone marrow-derived cells. Blood. 2005;105:1068–1077. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bento CF, Pereira P. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and the loss of the cellular response to hypoxia in diabetes. Diabetologia. 2011;54:1946–1956. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Albiero M, Menegazzo L, Boscaro E, et al. Defective recruitment, survival and proliferation of bone marrow-derived progenitor cells at sites of delayed diabetic wound healing in mice. Diabetologia. 2011;54:945–953. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-2007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Asahara T, Kawamoto A, Masuda H. Concise review: Circulating endothelial progenitor cells for vascular medicine. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1650–1655. doi: 10.1002/stem.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Clifford DM, Fisher SA, Brunskill SJ, et al. Stem cell treatment for acute myocardial infarction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD006536. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006536.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fadini GP, Agostini C, Avogaro A. Autologous stem cell therapy for peripheral arterial disease meta-analysis and systematic review of the literature. Atherosclerosis. 2010;209:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tanaka R, Masuda H, Kato S, et al. Autologous G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood CD34(+) cell therapy for diabetic patients with chronic non-healing ulcer. Cell Transplant. 2012;168:892–897. doi: 10.3727/096368912X658007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tanaka R, Vaynrub M, Masuda H, et al. Quality-control culture system restores diabetic endothelial progenitor cell vasculogenesis and accelerates wound closure. Diabetes. 2013;62:3207–3217. doi: 10.2337/db12-1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fadini GP, de Kreutzenberg SV, Mariano V, et al. Optimized glycaemic control achieved with add-on basal insulin therapy improves indexes of endothelial damage and regeneration in type 2 diabetic patients with macroangiopathy: A randomized crossover trial comparing detemir versus glargine. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:718–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]