Regardless of therapeutic or prophylactic indication, the number of women undergoing mastectomy in Canada is substantial, and higher in some areas of the country than others. This systematic review addresses nine specific questions and provides evidence-based strategies and recommendations for the management of patients who are candidates for breast reconstruction.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Breast reconstruction, Guideline, Mastectomy

Abstract

The side effects of mastectomy can be significant. Breast reconstruction may alleviate some distress; however, there are currently no provincial recommendations regarding the integration of reconstruction with breast cancer therapy. The purpose of the present article is to provide evidence-based strategies for the management of patients who are candidates for reconstruction. A systematic review of meta-analyses, guidelines, clinical trials and comparative studies published between 1980 and 2013 was conducted using the PubMed and EMBASE databases. Reference lists of publications were manually searched for additional literature. The National Guidelines Clearinghouse and SAGE directory, as well as guideline developers’ websites, were also searched. Recommendations were developed based on the available evidence. Reconstruction consultation should be made available for patients undergoing mastectomy. Tumour characteristics, cancer therapy, patient comorbidities, body habitus and smoking history may affect reconstruction outcomes. Although immediate reconstruction should be considered whenever possible, delayed reconstruction is acceptable when immediate is not available or appropriate. The integration of reconstruction and postmastectomy radiotherapy should be addressed in a multidisciplinary setting. The decision as to which type of procedure to perform (autologous or alloplastic with or without acellular dermal matrices) should be left to the discretion of the surgeons and the patient after providing counselling. Skin-sparing mastectomy is safe and appropriate. Nipple-sparing is generally not recommended for patients with malignancy, but could be considered for carefully selected patients. Immediate reconstruction requires resources to coordinate operating room time between the general and plastic surgeons, to provide supplies including acellular dermal matrices, and to develop the infrastructure needed to facilitate multidisciplinary discussions.

Abstract

La mastectomie peut avoir des effets secondaires importants. La reconstruction mammaire peut soulager une certaine détresse, mais il n’existe pas de recommandations provinciales sur l’intégration de la reconstruction au traitement du cancer du sein. Le présent article vise à fournir des stratégies fondées sur des données probantes sur la prise en charge des patientes candidates à la reconstruction. Les auteurs ont effectué une analyse systématique des méta-analyses, des lignes directrices, des essais cliniques et des études comparatives publiées entre 1980 et 2013 obtenus dans les bases de données PubMed et EMBASE. Ils ont fait des recherches manuelles dans les listes de référence des publications pour trouver d’autres articles. Ils ont également fouillé le National Guidelines Clearinghouse et le répertoire SAGE, de même que les sites Web des développeurs de lignes directrices. Ils ont fait des recommandations d’après les données probantes disponibles. Les patientes qui subissent une mastectomie devraient profiter d’une consultation sur la reconstruction. Les caractéristiques des tumeurs, le traitement du cancer, les comorbidités des patients, le phénotype corporel et les antécédents de tabagisme peuvent nuire aux résultats de la reconstruction. Même s’il faut envisager une reconstruction immédiate dans la mesure du possible, il est acceptable de la reporter lorsque ce n’est pas possible ou envisageable. Une équipe multidisciplinaire doit discuter de l’intégration de la reconstruction et de la radiothérapie après la mastectomie. Il faut laisser le chirurgien et le patient décider du type d’intervention à privilégier (autologue ou alloplastique, accompagnée ou non de matrices dermiques acellulaires) après avoir offert des conseils thérapeutiques. La mastectomie qui épargne la peau est sécuritaire et pertinente. Il n’est généralement pas recommandé d’épargner le mamelon chez les patientes ayant une tumeur maligne, mais on peut l’envisager auprès de patientes soigneusement sélectionnées. Il faut des ressources pour effectuer une reconstruction immédiate afin de coordonner le temps opératoire entre les plasticiens généraux et plastiques, de fournir le matériel, y compris les matrices dermiques acellulaires, et de prévoir l’infrastructure nécessaire pour faciliter les discussions multidisciplinaires.

Treatment for breast cancer largely favours breast conservation, when appropriate. Current guidelines regarding the surgical management of invasive breast cancer recommend lumpectomy and whole breast irradiation (ie, breast conservation therapy) as an oncologically equivalent option to mastectomy alone for patients with stage I–II disease (1,2). Despite these recommendations, the rate of mastectomy for unilateral invasive breast cancer remains high in some areas. In Alberta, for example, the rate was recently reported to be as high as 50%, compared with 32% for the rest of Canada (3). This difference may be due to patient preference, although no conclusions can be drawn from these epidemiological data. Furthermore, bilateral mastectomy is often performed prophylactically to reduce the risk of breast cancer and ovarian cancer in patients at high genetic risk (4–7). The population of women undergoing mastectomy in Canada is, in fact, considerable.

Whether for therapeutic or prophylactic reasons, the side effects of mastectomy can be significant for women. Anxiety and depression, poor body image, sexual issues and phantom breast syndrome have been well documented (8–16). Breast reconstruction may alleviate some of the postmastectomy distress experienced by these patients (17); however, the successful integration of breast reconstruction with breast cancer therapy first requires a standardized provincial approach. The purpose of the present article is to provide evidence-based strategies for the management of patients who are candidates for breast reconstruction. Specifically, the following questions are addressed:

Who is a candidate for postmastectomy breast reconstruction?

What types of breast reconstruction are available?

What is the appropriate timing of breast reconstruction?

Which factors can affect the outcomes of breast reconstruction?

What is the appropriate extent of mastectomy (ie, skin-sparing, nipple-sparing)?

What are the risks and benefits associated with breast reconstruction?

What is the appropriate post-breast reconstruction surveillance?

What is the role of acellular dermal matrix in implant-based breast reconstruction? and

What is the role of autologous fat grafting as an adjunct to breast reconstruction?

Recommendations are provided along with a review of the evidence.

METHODOLOGY

Guideline development

The review process for the present guideline was developed based on the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence overview of clinical guideline development for stakeholders, the public and the National Health Service (18); Cummings and Rivara’s (19) methodology on reviewing manuscripts for Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine; and the AGREE collaboration (20). With this methodological foundation, a working group consisting of two plastic surgeons with extensive experience in breast reconstruction, a general surgeon with expertise in breast cancer surgery and a cancer research methodologist drafted the guideline recommendations. The recommendations were reviewed by a province-wide panel of plastic surgeons and general surgeons and, finally, by an interdisciplinary group of physicians specializing in medical oncology, radiation oncology, clinical trials research and psychosocial oncology from the Alberta Breast Tumour Team. The evidence base for the present guideline was informed by a systematic review of the literature.

Literature search strategy

A systematic search for relevant literature related to breast reconstruction following prophylactic or therapeutic mastectomy was conducted using the PubMed and EMBASE databases (1980 to April 20, 2013). The search terms included “breast reconstruction” and (“cancer” or “neoplasm”) and results were limited to meta-analyses, systematic reviews, guidelines, randomized controlled trials, prospective cohort studies and retrospective case series. Reference lists of key publications were manually searched for additional literature. Guidelines on breast reconstruction were identified from a search of the National Guidelines Clearinghouse and the SAGE Directory of Cancer Guidelines databases (2006 to June 15, 2012), as well as individual guideline developers’ websites.

Publications were selected for inclusion in the systematic review if they reported outcomes related to oncological safety, time to adjuvant therapy, surgical complications and cosmesis, and/or quality of life. Qualitative or descriptive studies, opinion papers, letters and editorials were excluded from the literature review. Due to a lack of translation services, non-English language articles were excluded from the review of the evidence.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The literature search, coupled with a manual search of key publication reference lists, identified >150 publications on the role of breast reconstruction in the treatment and prophylaxis of breast cancer. Of these, 28 were considered to be high-level evidence (ie, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials and prospective comparative studies). Seven guidelines that discussed breast reconstruction (21–27) were included; however, none of these published guidelines focused specifically and solely on the procedure. Evidence and recommendations to address the nine key questions follow.

I. Who is a candidate for postmastectomy breast reconstruction?

Psychosocial morbidity (ie, anxiety, depression, body image, sexuality and self-esteem) can be significant in women undergoing mastectomy; however, breast reconstruction may alleviate some of the negative psychosocial effects of losing a breast (28). Furthermore, breast reconstruction following mastectomy is oncologically safe. A recent meta-analysis found that the risk of breast cancer recurrence among patients with breast cancer who underwent mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction was equivalent to those who underwent mastectomy alone (OR 0.98 [95% CI 0.62 to 1.54]) (29). Furthermore, breast reconstruction can achieve a high level of satisfaction and better psychosocial outcomes for patients (30–32).

Nevertheless, the rate of breast reconstruction has remained relatively low (<30%) in North America (33,34) compared with countries such as France (>80%) (35). Factors that are significantly associated with a lower rate of reconstruction among breast cancer patients include African American race or other minority races (versus Caucasian), nonmetropolitan (versus metropolitan) dwelling, receipt of radiation therapy, older age, married (versus never married or widowed) and unilateral mastectomy (versus prophylactic mastectomy of contralateral breast) (36–38). Other reasons for not undergoing reconstruction may include the presence of comorbidities or patient preference (39).

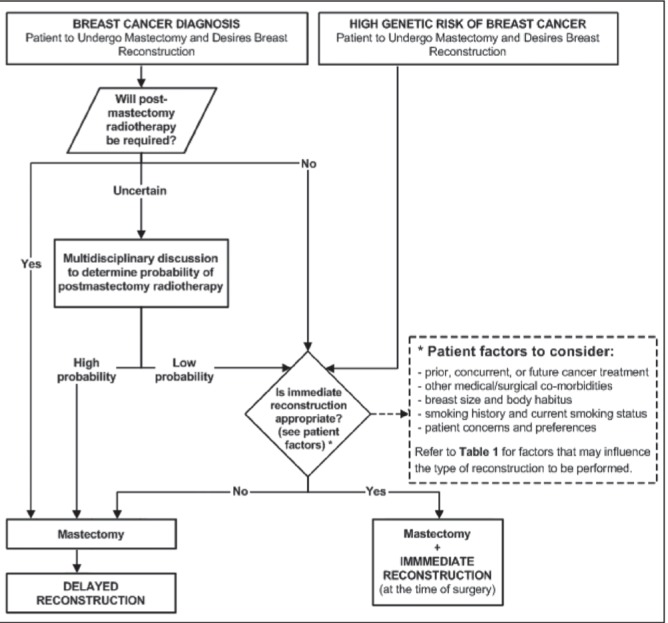

A proposed pathway for integrating breast reconstruction with mastectomy is shown in Figure 1. Adoption of this pathway would standardize the approach to women undergoing mastectomy and improve access to immediate breast reconstruction (40).

Figure 1).

Algorithm for the integration of breast reconstruction with prophylactic or therapeutic mastectomy

Recommendations:

Patients who are to undergo either prophylactic or therapeutic mastectomy should have access to breast reconstruction consultation. Various patient and treatment factors affect options, risks and outcomes of a woman’s breast reconstruction. Consultation with a specialist in breast reconstruction can provide a patient with a specialized treatment plan and anticipated outcomes so she can determine whether breast reconstruction is appropriate. Table 1 presents factors that may limit the options and outcomes of breast reconstruction.

TABLE 1.

Clinical factors to consider when deciding the timing and method of reconstruction

| Clinical factor |

Guidance according to reconstruction type

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate | Delayed | Evidence* | |

| Cancer-related factors | |||

| Ductal carcinoma in situ | Acceptable | Acceptable | Moderate |

| T1 or T2 tumours | Acceptable | Acceptable | Moderate |

| T3 or T4 | Not recommended | Acceptable | Moderate |

| Inflammatory breast cancer | Not recommended | Acceptable | Insufficient |

| Multicentric tumours | Acceptable | Acceptable | Insufficient |

| Suspicious, palpable axillary nodes | Not recommended | Acceptable | Insufficient |

| Positive premastectomy SLNB | Not recommended | Acceptable | Moderate |

| Treatment-related factors | |||

| Previous radiotherapy | Acceptable; favours autologous | Acceptable; favours autologous | Good |

| Prophylactic mastectomy | Acceptable | Acceptable | Good |

| Additional delay to surgery >3 weeks | Not recommended | Acceptable | Insufficient |

| Previous nononcological breast surgery | Acceptable | Acceptable | Moderate |

| After preoperative systemic therapy | Acceptable | Acceptable | Good |

| Before adjuvant chemotherapy | Acceptable | Acceptable | Good |

| Before adjuvant radiotherapy | Not recommended | Acceptable | Good |

| Previous diagnostic/excisional biopsy | Acceptable, but may affect skin sparing | Acceptable | Insufficient |

| Patient factors | |||

| Older age | Acceptable, but may affect risks | Acceptable, but may affect risks | Moderate |

| Obesity | Acceptable, but may affect risks | Acceptable, but may affect risks | Moderate |

| Diabetes | Acceptable, but may affect risks | Acceptable, but may affect risks | Moderate |

| Smoking | Acceptable, but may affect risks | Acceptable, but may affect risks | Moderate |

| Patient preference | Acceptable | Acceptable | Moderate |

| Planned future pregnancy | Acceptable; favors implants | Acceptable; favours implants | Insufficient |

Evidence levels: good – at least one well-designed randomized controlled trial or several comparative studies; moderate – noncomparative observational studies (ie, prospective and/or retrospective cohorts); insufficient – case reports or anecdotal evidence only (recommendations were consensus based in the absence of moderate or good evidence). SNLB Sentinel lymph node biopsy

II. What types of breast reconstruction are available?

Prosthetic implants and autologous tissue are available for breast reconstruction procedures. No randomized controlled trials have been performed to compare these two main methods of reconstruction in terms of cosmesis, complications and oncological safety in patients with breast cancer. Furthermore, the few observational studies available in the literature have used varying, nonstandardized measures to assess aesthetic outcomes (41,42). Factors such as cost (43), pain (44), aesthetics (45–47), feasibility with radiotherapy (48,49) and complication rates (50–53) have been used to rank one reconstructive procedure over another.

The available data suggest that there are pros and cons to each method. Transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous (TRAM) flap tends to be associated with greater aesthetic satisfaction than prosthetic reconstructions, but may cause more difficulties functioning at work or school, performing vigorous physical activities, participating in community or religious activities, and visiting with relatives (54). Lower complication rates have been observed with immediate expander/implant reconstructions (21.7%), versus latissimus dorsi (LD) flap reconstructions (67.9%) or TRAM flap reconstructions (26.9%), while reoperation rates were lower for TRAM flap reconstruction (5.8% versus 11.3% for expander/implant and 10.7% for LD flap) (55). While implant-assisted LD reconstruction and tissue-only autologous LD flap reconstruction have demonstrated equivalent short-term (zero to three months) and long-term (four to 12 months) complication rates (66% versus 51%, respectively [P=0.062] and 48% versus 45%, respectively [P=0.845]), role functioning and pain were significantly worse in the tissue-only group (P=0.002 for both) (56).

Recommendations:

Several types of breast reconstruction are available: these include implant-based reconstructions, combination reconstructions (ie, LD flap with implant), and autologous flap reconstructions using deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP), TRAM, or superficial inferior epigastric artery flaps. There is no evidence to suggest that one type of procedure can be recommended over another. The decision as to which type of reconstruction to use should be left to the discretion of the surgeons and the patient after providing counselling on the benefits and limitations of each procedure. Table 1 presents factors that may influence the type of reconstruction to be performed.

III. What is the appropriate timing of breast reconstruction?

In women undergoing breast reconstruction, the procedure can be performed immediately (ie, at the time of mastectomy), early (ie, within one year) or delayed (ie, more than one year later). The psychological morbidity and distress associated with delayed reconstruction has been reported to be higher than that of immediate or early reconstructions (10,15,16). Regarding safety, mastectomy alone and mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction have been shown prospectively to be equivalent at a median 70 months follow-up in terms of local recurrence (5.2% for immediate versus 9.4%), regional metastases (1.4% for immediate versus 1.3%), distant metastases (13.9% for immediate versus 16.4%), and overall survival (HR 1.03) and disease-free survival (HR 0.99). Radiotherapy was not given to any patients (57). Furthermore, a meta-analysis by Gieni et al (34) found no differences in terms of the risk of recurrence between patients who underwent immediate reconstruction and those who underwent mastectomy alone. Guidelines regarding this issue generally indicate that immediate reconstruction is as safe oncologically as delayed reconstruction and offers patients an improved psychological profile (23–27).

However, the need for adjuvant therapy, particularly radiotherapy in patients with T1/T2 node-positive breast cancer, T3/T4 breast cancer and any stage breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (58), complicates breast reconstruction following mastectomy. As a result, there has been much debate regarding the timing of mastectomy in patients requiring radiotherapy. Most guidelines that address the timing of adjuvant radiotherapy recommend that breast reconstruction be delayed, or at least, discussed in a multidisciplinary setting (22,24,27). Retrospective data from 102 breast cancer patients showed that late complications were significantly higher among patients who underwent immediate reconstruction followed by radiotherapy versus those who underwent radiotherapy followed by delayed TRAM flap reconstruction (87.5% versus 8.6%; P<0.001); the mean radiotherapy dose was 50 Gy to 51 Gy (59). Studies investigating complications in autologous reconstructions in patients undergoing radiotherapy have all demonstrated increased adverse events and events such as fat necrosis and major infection (60,61). A more recent meta-analysis of postoperative morbidity following immediate or delayed breast reconstruction (n=1105) found that patients undergoing radiotherapy were more likely to experience morbidity (OR 4.2 [95% CI 2.4 to 7.2]) but that autologous reconstruction was associated with less morbidity than implant-based reconstruction (OR 0.21 [95% CI 0.1 to 0.4]). Overall, this study found that delaying reconstruction until after radiotherapy had no significant effect on outcome (OR 0.87 [95% CI 0.47 to 1.62]) (62). Complications (eg, capsular contracture, pain, exposure and implant removal) among patients undergoing reconstruction with implants are also more frequent in patients receiving radiotherapy (63,64). A prospective study comparing timing of radiotherapy on permanent implants versus on tissue expanders (all two-stage immediate with subpectoral temporary expanders and permanent implants) found that the rate of failure (ie, removal of the implant, leaving the chest wall flat or change to a flap-based technique) was significantly higher when radiotherapy was delivered at the tissue expander stage rather than at the permanent implant stage (40% versus 6.4%; P<0.0001). The capsular contracture rate was similar for both groups (65). Retrospective data have shown that upfront staging sentinel lymph node biopsy may be useful in determining the probability of postmastectomy radiotherapy in clinically node-negative patients (66–71). No randomized controlled trials have been conducted to compare upfront staging with intraoperative staging in the setting of immediate reconstruction. Therefore, a recommendation cannot be made for or against either strategy.

Data suggest that immediate reconstruction can be safely integrated with chemotherapy without a significant impact on complications. A prospective randomized trial comparing modified radical mastectomy to neoadjuvant chemotherapy or hormone therapy followed by modified radical mastectomy (72) found that there was no significant difference in the risk of complications and that immediate breast reconstruction was not an independent predictor of complications. The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program’s reported wound complication rate among breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery was low (3.1%), with a nonsignificant trend toward increased complications in those who underwent immediate reconstruction (OR 1.58 [95% CI 0.98 to 2.58]) (73). Similar data have been reported elsewhere (74–81). It is important to acknowledge that reconstruction may impact the time to chemotherapy, but not necessarily in a clinically significant manner. A retrospective comparative study found that the mean time period between surgery and commencement of adjuvant treatment was 15 days longer in the immediate reconstruction group; delays were related to surgical complications (82). A prospective series of 391 consecutive women who underwent mastectomy or mastectomy and immediate reconstruction showed a statistically significant increase in the median time to chemotherapy (6.8 weeks for mastectomy alone versus 8.5 weeks for immediate reconstruction; P=0.01) (75); however, both remain within the generally accepted timeframe of systemic therapy commencing no longer than 12 weeks postoperatively. For women who have no requirements for adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment (ie, those undergoing prophylactic mastectomy) there is no reason to delay breast reconstruction.

Recommendations:

Patients undergoing prophylactic mastectomy should be considered for immediate breast reconstruction (ie, at the time of surgery). Patients undergoing therapeutic mastectomy who do not require postmastectomy radiotherapy should also be considered for immediate breast reconstruction because there is sufficient evidence to support the oncological safety of immediate reconstruction in these patients. Patients for whom radiotherapy is planned or highly likely should be discussed for breast reconstruction appropriateness in a multidisciplinary setting. In general, reconstruction should be delayed until after treatment with radiotherapy has been completed. For patients in whom the likelihood of radiotherapy after mastectomy is uncertain (eg, clinically staged node-negative T1 or T2 tumours), an ‘upfront’ staging sentinel lymph node biopsy could be considered as a separate, outpatient procedure to assist in determining the probability of postmastectomy radiotherapy before proceeding with mastectomy and immediate reconstruction. Data regarding the benefits and limitations of an ‘upfront’ sentinel lymph node biopsy are limited to retrospective case series only. Until randomized data are available to compare ‘upfront’ staging with intraoperative nodal evaluation or awaiting final pathological staging, one strategy cannot be recommended over another. Patients receiving other therapies, including chemotherapy, can be safely offered breast reconstruction, with no evidence of adverse effects on the outcome of reconstruction and no clinically important delay in chemotherapy or adverse effect on the efficacy of chemotherapy. Patients for whom immediate breast reconstruction is desired but is not appropriate may be considered for delayed breast reconstruction as an acceptable alternative.

IV. Which factors can affect the outcomes of breast reconstruction?

Outcomes of breast reconstruction may be influenced by both patient and tumour characteristics, which should be carefully assessed at the time of initial consultation. Reconstruction failure, defined as the need for a second operative intervention, including ablation/removal or replacement of a prosthesis, has been associated with larger tumour size (T3/T4), smoking and lymph node positivity in a study evaluating patients who undwent immediate implant-based reconstruction. The rate of failure was 7% for patients with none of these factors, 15.7% for patients with one, 48.3% for patients with two and 100% for patients with all three factors, accurately predicting 80% of failures (83). In a study involving patients who underwent both implant and autologous-based immediate reconstruction (n=374), a follow-up survey five years post-treatment found that the receipt of reconstruction did not vary according to body mass index (BMI): BMI <25 kg/m2 (53%); BMI 25 kg/m2 to 30 kg/m2 (48%); BMI >30 kg/m2 (45%) (P=0.43). However, reconstruction type did vary according to BMI: TRAM flaps were performed in 53% of patients with BMI >30 kg/m2 versus 26% of patients with BMI <25 kg/m2 (P=0.01). Patient satisfaction with surgical decision making and surgical outcomes was similar across BMI categories (84). Guidelines published by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) (21) and the Massachusetts Board of Registration in Medicine Expert Panel (27) list previous cancer therapy (ie, chemotherapy, radiotherapy), body composition and smoking status as factors to consider when selecting patients for reconstruction. The NCCN also adds comorbidities and patient concerns as factors to be considered.

Recommendations:

Factors that should be weighed when considering candidates for any breast reconstruction (immediate or delayed) include previous, concurrent or known future breast cancer treatment, patient comorbidities, body habitus, previous and current smoking status, behavioural/lifestyle factors, tumour stage and location, and risk of relapse (Table 1).

V. What is the appropriate extent of mastectomy?

The extent of mastectomy is an important factor affecting both cosmesis and functioning. A meta-analysis of data from nine studies including >3700 patients showed that skin-sparing mastectomy with immediate reconstruction was equivalent to conventional mastectomy without reconstruction in terms of local recurrence (6.2% for skin-sparing versus 4.0%; OR 1.25 [95% CI 0.81 to 1.94]) and distant relapse (10.0% for skin-sparing mastectomy versus 12.7%; OR 0.67 [95% CI 0.48 to 0.94]) (85). Consistent with these findings, some currently published guidelines recommend skin-sparing mastectomy as an acceptable approach (21,24,27). Nevertheless, skin-sparing mastectomy may be underutilized (86).

Nipple-sparing mastectomy performed in the setting of immediate reconstruction can achieve good cosmetic results (87) without recurrence when patients are carefully selected (ie, no disease within 2 cm of the nipple) (88). A prospectively maintained database of patients (n=428) undergoing nipple-sparing mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction for in situ cancer (16.9%), invasive cancer (45.8%) or prophylactic risk-reduction (37.3%) revealed a locoregional recurrence rate of 2% overall (median follow-up 28 months) and 2.4% among those with at least three years’ follow-up (median follow-up 45 months). Nipple tissue contained in situ cancer in 11 (1.7%) breasts and invasive cancer in nine (1.4%) (89). In a separate study, at 22.5 months, no local or regional recurrences were apparent in 45 prophylactic and 53 therapeutic mastectomies, among patients with tumours ≤3 cm in size and ≥2 cm from the nipple, no clinical invasion of the nipple-areola, no multicentric disease, negative intraoperative retroareolar frozen section and no nodal disease (90). The reported rate of nipple necrosis is quite low (approximately ≤1%) (91). Despite these and other studies (92,93) reporting promising results with nipple-sparing mastectomy, there are currently no randomized controlled trial data on the oncological safety of nipple-sparing compared with conventional skin-sparing mastectomy. Therefore, nipple-sparing mastectomy is generally not recommended for patients with malignancy (21,24,27).

Recommendations:

Skin-sparing mastectomy is acceptable for any patient who is a candidate for immediate breast reconstruction. Nipple-sparing mastectomy is generally not recommended for patients with malignancy. The decision as to whether to pursue a nipple-sparing procedure requires multidisciplinary input and discussion between the surgeons and the patient about potential additional risks associated with this approach.

VI. What are the risks and benefits associated with breast reconstruction?

As with any major surgery, complications can occur with breast reconstruction. The most common complications associated with autologous flap reconstructions are flap necrosis (5%), abdominal hernia or weakness (4%), infections (5%) and seroma (4%) (94). Reoperation is often required in patients who develop flap necrosis (95). Less common complications include bleeding and chronic pain (95,96). DIEP flaps have been shown to carry a higher risk for fat necrosis and flap loss (96) but lower donor-site morbidity (ie, bulge formation, hernia) (97,98) compared with muscle-sparing TRAM flaps. In patients who undergo implant-based breast reconstruction with human acellular dermal matrix (HADM), the total complication rate is approximately 15% and the most common complications are mastectomy flap necrosis (7%), infection (5%) and seroma (5%) (96). Mastectomy flap necrosis can necessitate reoperation and removal of the implants (86). As with autologous reconstruction, implant-based reconstruction may be associated with bleeding (86) and chronic pain (95,96). Implant rupture or malposition (63,64) and capsular contracture may occur more frequently in patients undergoing radiation therapy (83,99). Capsular contracture may be lower with the use of textured implants compared with smooth implants (100). In a very small group of patients with implants, anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) has been observed; however there is no evidence to conclude that breast implants cause ALCL (101) and most of the 34 cases reported up to 2010 were alive and well at the time of publication (102). The American Society of Plastic Surgeons and the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery have stated that ALCL is extremely rare, that the risk of women with implants developing ALCL is extremely low, and that breast implants are safe and effective (103).

Recommendations:

Patients should be made aware that breast reconstruction is a complex, major, multistep surgery and that complications can occur with any reconstruction. Patient expectations should be assessed before surgery to optimize satisfaction. In addition, patients should be made aware that cosmetic results may vary from patient to patient and that the reconstructive surgery will not restore the breast to its original appearance. Complications can occur with each type of reconstructive procedure. The most common complications associated with autologous reconstructions include seroma, scarring, hematoma, chronic back pain, flap failure, abdominal weakness, bulge or hernia, and necrosis; DIEP flaps carry a higher risk for fat necrosis and flap loss but lower donor-site morbidity (ie, bulge formation, hernia) compared with TRAM flaps. The most common complications associated with implant-based reconstructions include mastectomy skin flap necrosis, infection, seroma, hematoma, chronic breast pain, implant rupture or malposition, and capsular contracture. Textured implants carry a lower risk for capsular contracture compared with smooth implants.

VII. What is the appropriate post-breast reconstruction surveillance?

Imaging records from 227 patients with a history of postmastectomy breast reconstruction due to cancer showed that among 116 (51%) patients who underwent surveillance mammography of the reconstructed breast, only one recurrent cancer was detected in an autologous tissue flap reconstruction (0.86% detection rate of nonpalpable recurrent cancer), with a recall rate of 4% (104). Among 54 (24%) patients who presented with symptoms relating to breast reconstructions (most commonly lump or swelling), one-half were subsequently found to have no significant abnormality and one-third (29%) were found to have fat necrosis. Only four recurrences were found (105). Presently, assessment with ultrasound and mammography can only be supported in symptomatic patients, with surgical referral the most efficient means of obtaining a diagnosis while minimizing unnecessary tests or biopsies (106).

Recommendations:

There is no evidence to support routine screening mammography of the reconstructed breast in the absence of a palpable recurrence or symptoms of recurrence. Fat necrosis is a common and benign mammographic finding in patients with reconstructed breasts. Patients with suspicious masses or symptoms should be referred to a surgeon for examination and further workup.

VIII. What is the role of acellular dermal matrix in implant-based breast reconstruction?

Over the past decade, HADMs have been increasingly used to facilitate standard two-stage expander/implant immediate breast reconstructions as well as single-stage ‘direct-to-implant’ techniques. Aesthetic advantages of HADM-assisted techniques include better definition and control of the implant pocket, better infra- and lateral mammary fold definition, more natural ptosis and reduced rates of capsular contracture (107–109). Data from meta-analyses have revealed slightly higher rates of seroma, infection and flap necrosis for HADM-assisted reconstructions compared with traditional, non-HADM-assisted techniques (110,111), although pooling of early results from multiple surgeons’ initial experiences with the product may have biased the results (112). More recent studies have demonstrated that with judicious patient selection and precise intraoperative technique (113,114), superior aesthetic results can be achieved with a safety profile that is comparable with or superior to (115) reported series of traditional, non-HADM-assisted approaches (116–118). Certain questions surrounding HADM-assisted reconstruction have not yet been definitively answered, particularly whether the use of HADM results in reduced postoperative pain, shorter hospital stays and reduced expander fill times compared with traditional techniques (119,120). A multicentre prospective cohort study evaluating HADM-assisted immediate expander-based breast reconstruction (121) reported an overall complication rate of 4.6% (three of 65 breasts). The multicentre Canadian trial (NCT00956384) (122) comparing HADM-assisted single-stage, ‘direct-to-implant’ reconstruction with conventional two-stage expander implant reconstruction is currently underway and should clarify the role of HADM in ‘direct-to-implant’ reconstructions, and will also examine the cost effectiveness of the procedure.

Recommendations:

The use of HADM in immediate prosthetic breast reconstruction confers the potential benefits of improved aesthetic results, reduced rates of capsular contracture and implant malposition, and the possibility of a single-stage ‘direct-to-implant’ procedure for carefully selected patients. These benefits should be weighed against the potentially higher risks of postoperative seroma, infection and mastectomy skin flap necrosis in HADM-assisted prosthetic reconstruction when compared with traditional, non-HADM-assisted techniques. Based on consensus, the use of HADM in breast reconstruction should be at the discretion of the reconstructive surgeon in consultation with the patient and oncological team. Indications to use HADM include direct-to-implant single-stage reconstruction, and to gain increased control over infra- and lateral mammary fold position and ptosis in the setting of two-stage expander implant reconstruction.

IX. What is the role of autologous fat grafting as an adjunct to breast reconstruction?

As an adjunct to primary breast reconstruction, adipose tissue can be harvested and refined, then injected in small aliquots into the reconstructed breast, theoretically providing better structure and contour than could be achieved with an alloplastic or autologous reconstruction alone. There are currently no data from clinical trials or meta-analyses investigating autologous fat grafting (lipofilling). Observational studies have reported that patient-rated and surgeon-rated aesthetic satisfaction is high and well correlated (123,124). There are only limited data regarding the long-term oncological safety of lipofilling; however, one retrospective review did show that after a mean follow-up period of >40 months, fat grafting did not affect local tumour recurrence or survival (125). The most common complications with autologous fat grafting include fat necrosis (3.6%), oil cysts (1.8%) and infection (0.9%) (126–128). Complications appear to be higher with implant-based reconstructions compared with autologous flap reconstructions (129). Prosthetic durability of lipofilling is not well understood at this time (130).

Recommendations:

There are currently only limited data regarding the long-term oncological safety and long-term contour benefits of lipofilling for contour regularities after breast reconstruction. Data from comparative studies and case reports suggest that patient satisfaction is good; however, more data are needed before a recommendation for its use can be made.

CONCLUSIONS

To our knowledge, the present analysis is the most comprehensive systematic review to date on breast reconstruction following prophylactic or therapeutic mastectomy. We have presented data to show that breast reconstruction is oncologically safe and improves patient satisfaction and psychosocial well-being. There are many options for breast reconstruction, from the timing of the surgery with respect to mastectomy, to whether autologous tissue, an implant with autologous tissue or an HADM is used. Regardless, women undergoing mastectomy for prophylactic or therapeutic reasons should be given access to a reconstruction consultation.

SUMMARY

Breast reconstruction consultation should be made available to interested patients undergoing prophylactic or therapeutic mastectomy. Ideally, reconstruction in appropriate patients should be performed at the time of mastectomy, whenever possible. When immediate reconstruction is not performed, delayed reconstruction should be considered. Typically, reconstruction should be delayed until after treatment with radiotherapy has been completed. The implementation of immediate reconstruction requires, at minimum, resources to coordinate operating room time between the general and plastic surgeons, as well as infrastructure to facilitate multidisciplinary case discussions as appropriate.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of the Alberta Breast Tumour Team (CancerControl Alberta) and the Guideline Utilization Resource Unit (CancerControl Alberta) in the development of this clinical practice guideline. Members of the Alberta Breast Reconstruction Working Group: Dr Claire Temple-Oberle (Chair), Dr Lea Austen, Dr Earl Campbell, Dr Michael Chatenay, Dr Kelly Dabbs, Dr. William DeHaas, Dr Anthony Gomes, Dr Mark Haugrud, Dr Douglas Humphreys, Dr Jacqueline Kennedy, Dr Robert Lindsay, Dr Gregory McKinnon, Dr Blair Mehling, Dr David Olson, Dr May Lynn Quan, Dr Christiaan Schrag, Ms Melissa Shea-Budgell, Dr Sveta Silverman, Dr Rebecca Warburton, Dr Kirsten Westberg and Dr James Wolfli.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Breast Cancer Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Version 1.2012. < www.nccn.org> (Accessed August 10, 2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Cancer Care Ontario Program in Evidence-Based Care. Surgical Management of Early-Stage Invasive Breast Cancer. Practice Guideline Report #1-1 Version 2.2003 (updated 2010) < www.cancercare.on.ca/common/pages/UserFile.aspx?fileId=34102> (Accessed August 10, 2012).

- 3.Canadian Partnership Against Cancer and Canadian Institute for Health Information Breast Cancer Surgery in Canada, 2007–2008 to 2009–2010. < http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2012/icis-cihi/H115-61-2010-eng.pdf> (Accessed December 31, 2012).

- 4.CancerControl Alberta Treatment Guidelines: Risk Reduction and Surveillance Strategies for Individuals at High Genetic Risk for Breast and Ovarian Cancer. The Provincial Breast Tumour Team and the Guideline Utilization Resource Unit. < www.albertahealthservices.ca/hp/if-hp-cancer-guide-br011-hereditary-risk-reduction.pdf> (Accessed August 10, 2012).

- 5.Horsman D, Wilson BJ, Avard D, et al. National Hereditary Cancer Task Force Clinical management recommendations for surveillance and risk reduction strategies for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer among individuals carrying a deleterious BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007;29:45–60. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)32349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute of Clinical Excellence, UK Familial breast cancer. The classification and care of women at risk of familial breast cancer in primary, secondary and tertiary care. NICE clinical guideline 41. October 2006. < www.nice.org.uk> (Accessed August 10, 2012).

- 7.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Genetic/familial high risk assessment: Breast and ovarian. Practice Guidelines in Oncology version 1.2006. < www.nccn.org> (Accessed August 10, 2012).

- 8.Chen CL, Liao MN, Chen SC, Chan PL, Chen SC. Body image and its predictors in breast cancer patients receiving surgery. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35:E10–6. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182336f8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn LB, Cooper BA, Neuhaus J, et al. Identification of distinct depressive symptom trajectories in women following surgery for breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2011;30:683–92. doi: 10.1037/a0024366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metcalfe KA, Semple J, Quan ML, et al. Changes in psychosocial functioning 1 year after mastectomy alone, delayed breast reconstruction, or immediate breast reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:233–41. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1828-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skrzypulec V, Tobor E, Drosdzol A, Nowosielski K. Biopsychosocial functioning of women after mastectomy. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:613–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brandberg Y, Sandelin K, Erikson S, et al. Psychological reactions, quality of life, and body image after bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in women at high risk for breast cancer: A prospective 1-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3943–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spyropoulou AC, Papageorgiou C, Markopoulos C, Christodoulou GN, Soldatos KR. Depressive symptomatology correlates with phantom breast syndrome in mastectomized women. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;258:165–70. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0770-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schover LR. Sexuality and body image in younger women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1994;16:177–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schain WS, Wellisch DK, Pasnau RO, Landsverk J. The sooner the better: A study of psychological factors in women undergoing immediate versus delayed breast reconstruction. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:40–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.9.A40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wellisch DK, Schain WS, Noone RB, Little JW., III Psychosocial correlates of immediate versus delayed reconstruction of the breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76:713–8. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198511000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Ghazal SK, Fallowfield L, Blamey RW. Comparison of psychological aspects and patient satisfaction following breast conserving surgery, simple mastectomy and breast reconstruction. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:1938–43. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00197-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . How NICE clinical guidelines are developed: An overview for stakeholders, the public and the NHS. 4th edn. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummings P, Rivara FP. Reviewing manuscripts for Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:11–13. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.AGREE Collaboration Appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation (AGREE) instrument. < www.agreetrust.org/> (Accessed November 15, 2009).

- 21.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast Cancer. v1.2012. < www.nccn.org> (Accessed August 13, 2012).

- 22.Aebi S, Davidson T, Gruber G, Castiglione M, on behalf of the ESMO Guidelines Working Group Primary breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v9–v14. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.New Zealand Guidelines Group . Surgery for early invasive breast cancer. In: New Zealand Guidelines Group, editor. Management of Early Breast Cancer. Wellington: New Zealand Guidelines Group (NZGG); 2009. pp. 29–57. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaufmann M, Morrow M, Von MG, et al. Locoregional treatment of primary breast cancer: Consensus recommendations from an International Expert Panel. Cancer. 2010;116:1184–91. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Collaborating Centre for Cancer . Early and locally advanced breast cancer: Diagnosis and treatment (NICE clinical guideline; no. 80) London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE); 2009. p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dawood S, Merajver SD, Viens P, et al. International expert panel on inflammatory breast cancer: Consensus statement for standardized diagnosis and treatment. Ann Oncol. 2010;22:515–23. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee BT, Duggan MM, Keenan MT, et al. Massachusetts Board of Registration in Medicine Expert Panel on Immediate Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction following Mastectomy for Cancer. Commonwealth of Massachusetts Board of Registration in Medicine Expert Panel on immediate implant-based breast reconstruction following mastectomy for cancer: Executive summary. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:800–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nissen MJ, Swenson KK, Ritz LJ, Farrell JB, Sladek ML, Lally RM. Quality of life after breast carcinoma surgery: A comparison of three surgical procedures. Cancer. 2001;91:1238–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atisha D, Alderman AK, Lowery JC, Kuhn LE, Davis J, Wilkins EG. Prospective analysis of long-term psychosocial outcomes in breast reconstruction: Two-year postoperative results from the Michigan Breast Reconstruction Outcomes Study. Ann Surg. 2008;247:1019–28. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181728a5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guyomard V, Leinster S, Wilkinson M. Systematic review of studies of patients’ satisfaction with breast reconstruction after mastectomy. Breast. 2007;16:547–67. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xue DQ, Qian C, Yang L, Wang XF. Risk factors for surgical site infections after breast surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:375–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2012.02.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Temple C, Cook EF, Ross DC, et al. Development of a Breast Reconstruction Satisfaction Questionnaire (BRECON): Dimensionality and clinical importance of breast symptoms, donor site issues, patient expectations, and relationships. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:209–16. doi: 10.1002/jso.21477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dool JS. Reconstruction following mastectomy for stage I or stage II breast cancer – an epidemiologic study. 2005 Oct; Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary. Master of Science Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gieni M, Avram R, Dickson L, et al. Local breast cancer recurrence after mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction for invasive cancer: A meta-analysis. Breast. 2012;21:230–6. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ceradini DJ, Levine JP. Breast cancer reconstruction: More than skin deep. Prim Psych. 2008:72–80. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clark L, Holcombe C, Hill J, et al. Sexual abuse in childhood and postoperative depression in women with breast cancer who opt for immediate reconstruction after mastectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93:106–10. doi: 10.1308/003588411X12851639107593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alderman AK, Hawley ST, Janz NK, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of postmastectomy breast reconstruction: Results from a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5325–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joslyn SA. Patterns of care for immediate and early delayed breast reconstruction following mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:1289–96. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000156974.69184.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elmore L, Myckatyn TM, Gao F, et al. Reconstruction patterns in a single institution cohort of women undergoing mastectomy for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:3223–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2530-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Platt J, Baxter N, Zhong T. Breast reconstruction after mastectomy for breast cancer. CMAJ. 2011;183:2109–16. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pezner RD, Lipsett JA, Vora NL, et al. Limited usefulness of observer-based cosmesis scales employed to evaluate patients treated conservatively for breast cancer. Int J Radiation Oncology Biol Phys. 1985;11:1117–9. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(85)90058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kroll SS, Evans GRD, Reece GP, et al. Comparison of resource costs between implant-based and TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97:364–72. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199602000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kroll SS, Sharma S, Koutz C, et al. Postoperative morphine requirements of free TRAM and DIEP flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:338–41. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200102000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kroll SS, Baldwin B. A comparison of outcomes using three different methods of breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90:455–62. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199209000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clough KB, O’Donoghue JM, Fitoussi AD, et al. Prospective evaluation of late cosmetic results following breast reconstruction: II. TRAM flap reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1710–6. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200106000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clough KB, O’Donoghue JM, Fitoussi AD, et al. Prospective evaluation of late cosmetic results following breast reconstruction: I: Implant reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1702–9. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200106000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cordeiro PG, Pusic AL, Disa JJ, et al. Irradiation after immediate tissue expander/implant breast reconstruction: Outcomes, complications, aesthetic results, and satisfaction among 156 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:877–81. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000105689.84930.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams JK, Carlson GW, Bostwick III, et al. The effects of radiation treatment after TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100:1153–60. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199710000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blondeel PN, Vanderstraeten CG, Monstrey SJ, et al. The donor site morbidity of free DIEP flaps and free TRAM flaps for breast reconstruction. Br J Plast Surg. 1997;50:322–30. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(97)90540-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blondeel PN. One hundred free DIEP flap breast reconstructions: A personal experience. Br J Plast Surg. 1999;52:104–11. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1998.3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grotting JC. The free abdominoplasty flap for immediate breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 1991;27:351–54. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199110000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Allen RJ, Treece P. Deep inferior epigastric perforator flap for breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 1994;32:32–8. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199401000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Klok JA, Cordeiro PG, Cano SJ. Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: The BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:345–53. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spear SL, Newman MK, Bedford MS, Schwartz KA, Cohen M, Schwartz JS. A retrospective analysis of outcomes using three common methods for immediate breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:340–7. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31817d6009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eriksen C, Lindgren EN, Frisell J, Stark B. A prospective randomized study comparing two different expander approaches in implant-based breast reconstruction: One stage versus two stages. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:254e–64e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182589ba6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Winters ZE, Haviland J, Balta V, Benson J, Reece-Smith A, Betambeau N. Prospective Trial Management Group. Integration of patient-reported outcome measures with key clinical outcomes after immediate latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction and adjuvant treatment. Br J Surg. 2013;100:240–51. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Petit JY, Gentilini O, Rotmensz N, et al. Oncological results of immediate breast reconstruction: Long term follow-up of a large series at a single institution. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112:545–9. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9891-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alberta Health Services. Provincial Breast Tumour Team Adjuvant Radiation Therapy for Invasive Breast Cancer<www.albertahealthservices.ca/hp/if-hp-cancer-guide-br005-adjuvant-rtinvasive-breast.pdf> (Accessed August 15, 2012).

- 59.Tran NV, Chang DW, Gupta A, et al. Comparison of immediate and delayed free TRAM flap breast reconstruction in patients receiving postmastectomy radiation therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:78–82. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200107000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Williams JK, Bostwick J, III, Bried JT, Mackay G, Landry J, Benton J. TRAM flap breast reconstruction after radiation treatment. Ann Surg. 1995;221:756–64. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199506000-00014. discussion 764–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Javaid M, Song F, Leinster S, Dickson MG, James NK. Radiation effects on the cosmetic outcomes of immediate and delayed autologous breast reconstruction: An argument about timing. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barry M, Kell MR. Radiotherapy and breast reconstruction: A meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127:15–22. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1401-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Evans GR, Schusterman MA, Kroll SS, et al. Reconstruction and the radiated breast: Is there a role for implants? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:1111–5. discussion 1116–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kronowitz SJ, Robb GL. Radiation therapy and breast reconstruction: A critical review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:395–408. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nava MB, Pennati AE, Lozza L, Spano A, Zambetti M, Catanuto G. Outcome of different timings of radiotherapy in implant-based breast reconstructions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:353–9. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31821e6c10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McGuire K, Rosenberg AL, Showalter S, Brill KL, Copit S. Timing of sentinel lymph node biopsy and reconstruction for patients undergoing mastectomy. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;59:359–63. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3180326fb9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schrenk P, Woelfl S, Bogner S, Moser F, Wayand W. The use of sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer patients undergoing skin sparing mastectomy and immediate autologous reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1278–86. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000181515.11529.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Christante D, Pommier SJ, Diggs BS, et al. Using complications associated with postmastectomy radiation and immediate breast reconstruction to improve surgical decision making. Arch Surg. 2010;145:873–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mannu GS, Navi A, Morgan A, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy before mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction may predict post-mastectomy radiotherapy, reduce delayed complications and improve the choice of reconstruction. Int J Surg. 2012;10:259–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brady B, Fant J, Jones R, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy followed by delayed mastectomy and reconstruction. Am J Surg. 2003;185:114–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)01205-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wood BC, David LR, Defranzo AJ, et al. Impact of sentinel lymph node biopsy on immediate breast reconstruction after mastectomy. Am J Surg. 2009;75:551–6. discussion 556–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Forouhi P, Dixon JM, Leonard RC, Chetty U. Prospective randomized study of surgical morbidity following primary systemic therapy for breast cancer. Br J Surg. 1995;82:79–82. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Decker MR, Greenblatt DY, Havlena J, Wilke LG, Greenberg CC, Neuman HB. Impact of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on wound complications after breast surgery. Surgery. 2012;152:382–8. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Donker M, Hage JJ, Woerdeman LA, Rutgers EJ, Sonke GS, Vrancken Peeters MJ. Surgical complications of skin sparing mastectomy and immediate prosthetic reconstruction after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for invasive breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhong T, Hofer SO, McCready DR, Jacks LM, Cook FE, Baxter N. A comparison of surgical complications between immediate breast reconstruction and mastectomy: The impact on delivery of chemotherapy – an analysis of 391 procedures. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:560–6. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1950-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Caffo O, Cazzolli D, Scalet A, et al. Concurrent adjuvant chemotherapy and immediate breast reconstruction with skin expanders after mastectomy for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;60:267–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1006401403249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Giacalone PL, Rathat G, Daures JP, Benos P, Azria D, Rouleau C. New concept for immediate breast reconstruction for invasive cancers: Feasibility, oncological safety and esthetic outcome of post-neoadjuvant therapy immediate breast reconstruction versus delayed breast reconstruction: A prospective pilot study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;122:439–51. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0951-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mitchem J, Herrmann D, Margenthaler JA, Aft RL. Impact of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on rate of tissue expander/implant loss and progression to successful breast reconstruction following mastectomy. Am J Surg. 2008;196:519–22. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oh E, Chim H, Soltanian HT. The effects of neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy on the surgical outcomes of breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:e267–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2012.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Azzawi K, Ismail A, Earl H, Forouhi P, Malata CM. Influence of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on outcomes of immediate breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1–11. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181da8699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vandeweyer E, Deraemaecker R, Nogaret JM, Hertens D. Immediate breast reconstruction with implants and adjuvant chemotherapy: A good option? Acta Chir Belg. 2003;103:98–101. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2003.11679374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kontos M, Lewis RS, Lüchtenborg M, Holmberg L, Hamed H. Does immediate breast reconstruction using free flaps lead to delay in the administration of adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:745–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cowen D, Gross E, Rouannet P, et al. Immediate post-mastectomy breast reconstruction followed by radiotherapy: Risk factors for complications. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;121:627–34. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0791-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kulkarni AR, Katz S, Hamilton AS, Graff JJ, Alderman AK. Patterns of use and patient satisfaction with breast reconstruction among obese patients: Results from a population-based study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:263–70. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182589af7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lanitis S, Tekkis PP, Sgourakis G, Dimopoulos N, Al Mufti R, Hadjiminas DJ. Comparison of skin-sparing mastectomy versus non-skin-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Surg. 2010;251:632–9. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d35bf8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shen J, Ellenhorn J, Qian D, Kulber D, Aronowitz J. Skin-sparing mastectomy: A survey based approach to defining standard of care. Am J Surg. 2008;74:902–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Petit JY, Veronesi U, Orecchia R, et al. The nipple-sparing mastectomy: Early results of a feasibility study of a new application of perioperative radiotherapy (ELIOT) in the treatment of breast cancer when mastectomy is indicated. Tumori. 2003;89:288–91. doi: 10.1177/030089160308900311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wijayanayagam A, Kumar AS, Foster RD, Esserman LJ. Optimizing the total skin-sparing mastectomy. Arch Surg. 2008;143:38–45. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.1.38. discussion 45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Warren Peled A, Foster RD, Stover AC, et al. Outcomes after total skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate reconstruction in 657 breasts. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:3402–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2362-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Maxwell GP, Storm-Dickerson T, Whitworth P, Rubano C, Gabriel A. Advances in nipple-sparing mastectomy: Oncological safety and incision selection. Aesthet Surg J. 2011;31:310–9. doi: 10.1177/1090820X11398111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stolier AJ, Sullivan SK, Dellacroce FJ. Technical considerations in nipple-sparing mastectomy: 82 consecutive cases without necrosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1341–7. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9753-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Voltura AM, Tsangaris TN, Rosson GD, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: Critical assessment of 51 procedures and implications for selection criteria. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3396–401. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sacchini V, Pinotti JA, Barros AC, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer and risk reduction: Oncologic or technical problem? J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:704–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kim JY, Davila AA, Persing S, et al. A meta-analysis of human acellular dermis and submuscular tissue expander breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:28–41. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182361fd6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dell DD, Weaver C, Kozempel J, Barsevick A. Recovery after transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap breast reconstruction surgery. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:189–96. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.189-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Man LX, Selber JC, Serletti JM. Abdominal wall following free TRAM or DIEP flap reconstruction: A meta-analysis and critical review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:752–64. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31818b7533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Egeberg A, Rasmussen MK, Ahm Sørensen J. Comparing the donor-site morbidity using DIEP, SIEA or MS-TRAM flaps for breast reconstructive surgery: A meta-analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:1474–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Futter CM, Weiler-Mithoff E, Hagen S, et al. Do pre-operative abdominal exercises prevent post-operative donor site complications for women undergoing DIEP flap breast reconstruction? A twocentre, prospective randomised controlled trial. Br J Plast Surg. 2003;56:674–83. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(03)00362-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Scuderi N, Alfano C, Campus GV, et al. Multicenter study on breast reconstruction outcome using Becker implants. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2011;35:66–72. doi: 10.1007/s00266-010-9559-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Barnsley GP, Sigurdson LJ, Barnsley SE. Textured surface breast implants in the prevention of capsular contracture among breast augmentation patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:2182–90. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000218184.47372.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.U.S. Food and Drug Administration Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) in women with breast implants: Preliminary FDA findings and analyses. < www.fda.gov> (Accessed September 13, 2012).

- 102.Eaves FF, Haeck PC, Rohrich RJ. Breast implants and anaplastic large cell lymphoma: Using science to guide our patients and plastic surgeons worldwide. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:2501–3. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31821787e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.American Society of Plastic Surgeons Important Health News on Breast Implants. < www.plasticsurgery.org> (Accessed September 13, 2012).

- 104.Sim YT, Litherland JC. The use of imaging in patients post breast reconstruction. Clin Radiol. 2012;67:128–33. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2011.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Barnsley GP, Grunfeld E, Coyle D, Paszat L. Surveillance mammography following the treatment of primary breast cancer with breast reconstruction: A systematic review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:1125–32. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000279143.66781.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zakhireh J, Fowble B, Esserman LJ. Application of screening principles to the reconstructed breast. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:173–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.7588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Jansen LA, Macadam SA. The use of AlloDerm in postmastectomy alloplastic breast reconstruction: Part I. A systematic review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:2232–44. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182131c56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jansen LA, Macadam SA. The use of AlloDerm in postmastectomy alloplastic breast reconstruction: Part II. A cost analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:2245–54. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182131c6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Vardanian AJ, Clayton JL, Roostaeian J, et al. Comparison of implant-based immediate breast reconstruction with and without acellular dermal matrix. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:403–10e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31822b6637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ho G, Nguyen TJ, Shahabi A, Hwang BH, Chan LS, Wong AK. A systematic review and meta-analysis of complications associated with acellular dermal matrix-assisted breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2012;68:346–56. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31823f3cd9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hoppe IC, Yueh JH, Wei CH, Ahuja NK, Patel PP, Datiashvili RO. Complications following expander/implant breast reconstruction utilizing acellular dermal matrix: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eplasty. 2011;11:e40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Salzberg CA. Focus on technique: One-stage implant-based breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:95S–103S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318262e1a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kim JY, Connor CM. Focus on technique: Two-stage implant-based breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;140:104S–15S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31825f2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Colwell AS, Damjanovic B, Zahedi B, Medford-Davis L, Hertl C, Austen WG., Jr Retrospective review of 331 consecutive immediate single-stage implant reconstructions with acellular dermal matrix: Indications, complications, trends, and costs. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:1170–78. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318230c2f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Cordeiro PG, McKarthy CM. A single surgeon’s 12-year experience with tissue expander/implant basted breast reconstruction: Part I. A prospective analysis of early complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:8225–831. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000232362.82402.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Cordeiro PG, McCarthy CM. A single surgeon’s 12-year experience with tissue expander/implant bresast reconstruction: Part II. An analysis of long-term complications, aesthetic outcomes, and patient satisfaction. Plast Recosntr Surg. 2006;118:832–39. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000232397.14818.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Handel N, Cordray Y, Gutierrez J, Jensen JA. A long-term study of outcomes, complications, and patient satisfaction with breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:757–67. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000201457.00772.1d. discussion 768–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.McCarthy CM, Lee CN, Halvorson EG, et al. The use of acellular dermal matrices in two-stage expander/implant reconstruction: A multicenter, blinded, randomized controlled trial. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(5 Suppl 2):57S–66S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31825f05b4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Preminger BA, McCarthy CM, Hu QY, Mehrara BJ, Disa JJ. The influence of AlloDerm on expander dynamices and complications in the setting of immediate tissue expander/implant reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;60:510–3. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31816f2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Venturi ML, Mesbahi AN, Boehmler JH, IV, Marrogi AJ. Evaluating sterile human acellular dermal matrix in immediate expander-based breast reconstruction: A multicenter, prospective, cohort study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:9e–18e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182729d4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sbitany H, Sandeen SN, Amalfi AN, Davenport MS, Langstein HN. Acellular dermis-assisted prosthetic breast reconstruction versus complete submuscular coverage: A head-to-head comparison of outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:1735–40. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181bf803d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Clinical Trials.gov One-stage breast reconstruction using dermal matrix/Implant versus two-stage expander/implant procedure (AllodermRCT) < http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00956384> (Accessed February 26, 2013).

- 123.Sarfati I, Ihrai T, Duvernay A, Nos C, Clough K. [Autologous fat grafting to the postmastectomy irradiated chest wall prior to breast implant reconstruction: A series of 68 patients.] Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2012:S0294–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.anplas.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Seth AK, Hirsch EM, Kim JY, Fine NA. Long-term outcomes following fat grafting in prosthetic breast reconstruction: A comparative analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:984–90. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318267d34d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Mestak O, Zimovjanová M. Breast reconstruction by autologous fat transfer. Rozhl Chir. 2012;91:373–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.de Blacam C, Momoh AO, Colakoglu S, Tobias AM, Lee BT. Evaluation of clinical outcomes and aesthetic results after autologous fat grafting for contour deformities of the reconstructed breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:411e–418e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31822b669f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Losken A, Pinell XA, Sikoro K, Yezhelyev MV, Anderson E, Carlson GW. Autologous fat grafting in secondary breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;66:518–22. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181fe9334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Pérez-Cano R, Vranckx JJ, Lasso JM, et al. Prospective trial of adipose-derived regenerative cell (ADRC)-enriched fat grafting for partial mastectomy defects: the RESTORE-2 trial. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:382–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2012.02.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Alderman AK, Kuhn LE, Lowery JC, et al. Does patient satisfaction with breast reconstruction change over time? Two-year results of the Michigan Breast Reconstruction Outcomes Study. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Cigna E, Ribuffo D, Sorvillo V, et al. Secondary lipofilling after breast reconstruction with implants. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16:1729–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]