Abstract

The global fight against HIV is progressing; however, women living in rural areas particularly in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) continue to face the devastating consequences of HIV and AIDS. Lack of knowledge and geographical barriers to HIV services are compounded by gender norms often limiting the negotiation of safe sexual practices among women living in rural areas. This paper discusses findings from a qualitative study conducted in rural areas of Mozambique examining factors that influenced women to engage in HIV risk-reduction practices. The findings from this study led to the emergence of an HIV and AIDS risk assessment and reduction (HARAR) model, which is described in detail. The model helps in understanding gender-related factors influencing men and women to engage in risk-reduction practices, which can be used as a framework in other settings to design more nuanced and contextual policies and programs.

Keywords: HIV, gender, risk reduction, rural women

Introduction

The fight against HIV globally is progressing, yet the impact of HIV remains pronounced among marginalized and disempowered individuals, many of whom are women living in rural areas.1 Across sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), there is a gender dynamic linked to HIV risk, with more women than men affected and infected with HIV.2 Women living in rural areas, particularly in SSA, face not only geographical barriers in terms of accessing HIV knowledge and services but also entrenched gender norms that often limit their ability to negotiate safe sex behaviors.3

Gender roles and expectations have been implicated in increased HIV risk and are partially responsible, alongside demographic population structures, for differences in infection rates between men and women. Inequalities in gender relations are a critical factor influencing HIV rates, particularly in SSA according to a number of studies examining global HIV trends.2–5 Although a vast array of literature has noted the consequences of gender inequality and inequity on increasing HIV risk,4,6,7 very few studies have examined the manner in which men and women work within existing gender norms to mitigate their perceived risk. There are important differences between women and men in the underlying mechanisms of infection and in the social and economic consequences of HIV. These originate from biological and socially constructed gender differences between women and men in terms of roles and responsibilities, access to resources, agency, and self-efficacy. Cultural constructs of femininity and masculinity are intertwined with other social dimensions, such as the division of labor within the household, and power inequalities within relationships according to gender and power theory.8 Understanding the interface between local gender norms and HIV risk is thus essential in mounting appropriate program and policy responses.

This paper discusses the application of findings from a qualitative study examining the interaction between gender norms and HIV risk-reduction practices in rural areas of northern Mozambique. An HIV and AIDS risk assessment and reduction (HARAR) model emerging from the research is used to analyze findings at individual, normative, social learning, and structural levels.

Methods

Data were collected over a six month period in mid-2008 across four villages in the province of Cabo Delgado in northern Mozambique. The villages of Mahate (~2,706 inhabitants) and Bilibiza (~4,056 inhabitants) in Quissanga district, and the villages of Mieze (~4,109 inhabitants) and 25 de Junho (~4,034 inhabitants) in Pemba-Metuge district comprised the study sites.9 A three-pronged approach was used: (1) interviews with village chiefs and traditional leaders, (2) participatory exercises with gender-specific groups, and (3) in-depth interviews. A total of 4 leader interviews, 16 group discussions, and 29 in-depth interviews were conducted over the time period.

Interviews with leaders in each village were conducted because of their critical role in shaping and maintaining social norms.10 As the primary aim was to seek permission from leaders and because information detailed in the leader interviews replicated those from group discussions, these discussions were not incorporated into the analysis.

Respondents for the group discussion were selected based on purposive and nonrandom sampling. In each village, leaders selected individuals from naturally existing groups or those formed through development interventions.

Participatory group sessions were conducted to determine HIV knowledge and explore perceptions of risk among respondents. For ethical reasons, participants were not asked whether they knew their own HIV status.

Interviews and group discussions were used to examine factors motivating men and women to respond to HIV risk while also providing a more holistic perspective on their beliefs, attitudes, and practices.

The positive deviance (PD) approach was used to identify individuals from group discussions for in-depth interviews. PD has primarily been used to inform program interventions, but the approach in identifying “good practices and behaviors” is of particular use for research studies seeking to better understand the factors that influence individuals to engage in healthy behaviors. It is based on the premise that there are some individuals who engage in certain behavior and find solutions to problems11 such as taking measures to reduce HIV risk, compared to others in their community, despite living in the same conditions and having the same access to resources. As behaviors are already undertaken by individuals in similar situations and contexts, they are more likely to be accepted and sustained.12 The approach was initially used to identify the practices of mothers who have healthy infants even though they live in conditions of poverty. PD has since been extended and applied to child growth,13 breastfeeding,14 and birth outcomes.15 For this research, PD was used to help identify individuals and assess the extent of the relationship between the following: (1) individuals already taking action to reduce their HIV risk, given that Demographic and Health Survey data16 indicate a general lack of risk-reduction knowledge and practices among men and women and (2) those who hold gender balanced attitudes, given that widespread gender disparities exist in the country.

Given the prominence of grounded theory in influencing rigorous qualitative analysis, the research adapted techniques from the theory17,18 including “constant comparative analysis” to compare and contrast themes across gender and age groups.

Conceptual framework

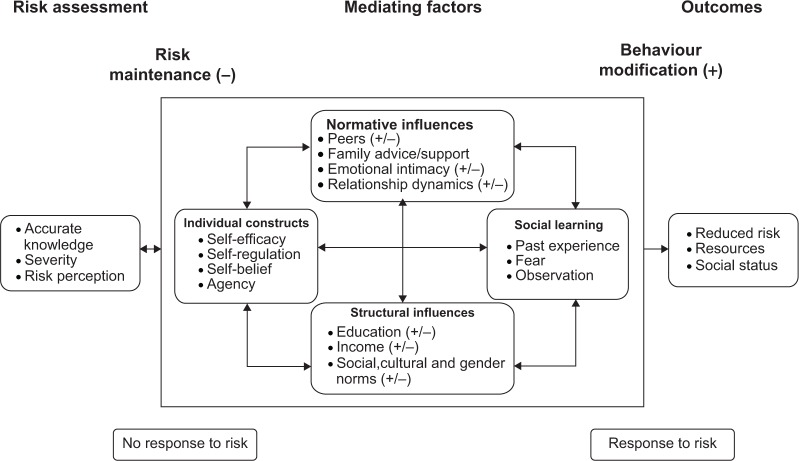

The conceptual framework used to guide the research was developed from the theory of triadic influence (TTI), to account for the multiple levels of influence on norms, attitudes, and behavior, with gender and power theory used to collate findings across levels. Based on the literature indicating that factors at a multitude of levels affect HIV risk and to escape focusing on factors solely at the individual level, an ecological approach was used to guide this study. Many ecological frameworks exist but do not always clearly mark the dynamic and integral nature of different levels (ie individual, family, and community). TTI examines the interplay of risk factors for health outcomes at multiple levels.19 An adapted version of TTI served as the conceptual framework (see Fig. 1) for this study by preserving individual, family, and community levels with corresponding theoretical constructs. However, specific factors from the literature that inhibit or enable risk-reduction practices were inserted at each level (individual, social normative, and structural) alongside corresponding constructs such as self-efficacy, social norms, and social construction. TTI helped to account for the close relationship between the various factors under each of the levels that can combine to influence beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors on gender roles or HIV risk. Factors incorporated within each of the levels can be both enabling and inhibiting in terms of influencing an increase or decrease in HIV risk. Thus, TTI facilitated in guiding the development of research methods to ensure factors at multiple levels were captured as well as identified factors that were most influential in motivating men and women to enact change. Theoretical constructs at each level helped better understand and substantiate research findings. Based on their use in previous studies, self-efficacy was used to examine factors at the individual level, while social norm and social construction were applied to factors at the social normative and structural levels, respectively. Self-efficacy, defined as an individual’s belief of their capability in implementing certain actions to produce a desired effect,20 was a key construct used in this study because despite factors at multiple levels that can influence risk reduction, it is ultimately the decision of the individual to act upon it. The construct was also used to help identify positive deviant cases.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

Results: HARAR Model

The study explored ways in which local constructions of gender norms, particularly among women, influence and motivate responses to HIV in rural Mozambique. Models and theories analyzing HIV behavior change, including the AIDS Risk Reduction Model (ARRM),21 the health belief model,22 and social cognitive theories,23,24 are important for understanding how risk is assessed and behavior is altered to reduce risk. Despite their utility, a key limitation of such approaches is their focus on the individual, with minimal attention directed at the social and relationship norms that influence sexual risk taking. In addition, emphasis is placed on risk recognition and identification, which does not necessarily translate into an individual taking action. There may also be other factors at play that prevent individuals from reducing their risk including lack of desire or a partner who may not be amenable to change. Moreover, the models and theories are homogenous in that they do not account for gender or the different challenges faced by men and women in responding to perceived HIV risk. This research found that factors at a multitude of levels including individual, normative, social learning, and structural levels were important in shaping HIV risk and responsive action, adding to the increasing body of literature indicating the importance of an ecological approach to approach to HIV and Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI) prevention and treatment.25–28

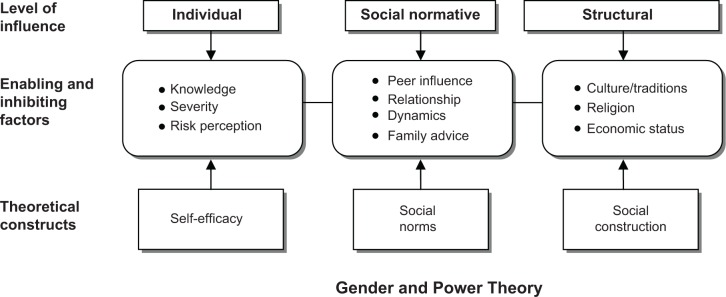

The initial conceptual framework and related theories were useful in understanding risk patterns among individuals, particularly factors at multiple levels that can influence risk. However, findings from the research demonstrated a more complex interplay between the various levels, which tend to operate in an interlinked and more cyclical manner than the TTI framework allowed. These are incorporated into the HARAR model (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

HARAR model.

The model supports and adapts elements from the health belief model29,30 and ARRM21 on risk perception, severity of the HIV epidemic and knowledge, as well as from social cognitive theories,20 which focus on learning and normative influences. It also encompasses the TTI and principles of ecological models by considering the multiple factors that influence risk and risk reduction. In addition, the research also demonstrated that the performative roles of men and women are prominent in both risk and risk reduction practices. Unlike most ecological models, however, HARAR distinguishes the various levels to highlight factors which may operate in isolation, but also recognizes that factors combine and interact at many levels to influence not only risk assessment, which the majority of models focus on, but also risk-reduction efforts. Importantly, the findings suggest that men and women go through three key phases (ie risk assessment, mediating factors, and outcomes) when at HIV risk which in turn influences whether action will be taken. Therefore, the initial conceptual framework has been modified and placed into the HARAR model taking into account the research findings.

Factors at the individual level in the conceptual framework, specifically knowledge, severity of the HIV epidemic, and risk perception were shifted in HARAR under the “risk assessment” phase as these factors have been noted in this research as crucial preconditions for individuals to engage in responsive measures. Factors in the conceptual model under social normative and structural influences have been preserved in the HARAR model under the “mediating factors” phase along with some modifications. In addition to the factors under structural influences in the conceptual framework, social and gender norms were included because of the inhibiting and enabling role they play on risk and risk-reduction efforts. The specific roles of men and women which are culturally defined and socially enacted, as postulated through gender and power8 as well as role and script theories31,32 shape identity and interaction with others as noted in this research. Since sexual encounters are the primary mode of HIV transmission in the study setting, the manner in which men and women identify with their gender and how they learn about and act out their expected roles in society are critical to understand if the dynamics of and responses to HIV risk are to be effectively tackled. As noted by the work of many leading gender and human sexuality theorists,33–37 is the notion of fluid gender roles within discourses of shifting cultural and social norms and where multiple forms of masculinity and femininity co-exist which can transcend sexes based on experiences. Such notions were reaffirmed in this study in the context of HIV risk reduction where at times, men reconstructed widely accepted norms of masculinity, such as the display of power through multiple sexual encounters, and instead prioritized the provider role in order to protect their family from harm. Similarly, women redefined norms of femininity (ie passivity and dependence) by removing themselves from risky situations through self-efficacious and autonomous actions. Under normative influences in the HARAR model, one factor, “emotional intimacy” was added based on findings from this research which demonstrated how it can be both protective or contribute to risk. Individual constructs and social learning were other components added under “mediating factors” as each were critical in shaping both perception of risk and subsequent action. With the exception of self-efficacy, none of the other factors noted under individual constructs or social learning in the HARAR model were in the original conceptual framework. Finally, although the conceptual framework was developed with one outcome in mind—HIV risk reduction—it was evident from this research that in many cases, other outcomes were just as or more important to motivate action, such as the need to maintain a good social standing and/or contain resources. These findings reinforce the need for HIV-related interventions to take on a holistic approach by considering the multiple factors of influence on risk perception and responses, particularly, that risk-reduction efforts may not always be the intended or immediate outcome motivating changes in practices. It also highlights the vital role of the often evolving role of gender dynamics in both HIV risk and risk-reduction practices.

Individuals assess their risk based on accurate knowledge, personal susceptibility, and severity in terms of the prevalence of HIV. Inaccurate knowledge such as notions that HIV is spread through condoms or that it only affects certain groups of people influences risk perception and subsequent mitigating responses. Thus, although many ecological models, including the TTI, state the importance of factors at a multitude of levels in influencing risk, individuals must have accurate knowledge, feel HIV is a severe threat in their lives, and perceive that they may be at risk before they decide to act on it.

HIV increases because people have many partners and they change women or men in whichever manner, these people have no control. We know the information that we must use condoms but we don’t want to use it.

—Participant in Married Male Group, Village B

We fear going to the GATV (voluntary counselling and testing site) and being told that we have HIV. I am afraid to get tested, when you are told that you are HIV positive that is where you want to hang yourself.

—Participant in Unmarried Male Group, Village D

Once risk is assessed, there are factors at the individual, normative, social learning, and structural levels that operate in a cyclical and interactive manner that can mediate this risk and either cause individuals to maintain risk levels (ie no response to risk) or move toward behavior modification (ie responses to risk). Men and women who take measures in response to perceived risk also do so to achieve other outcomes, such as maintaining a good social standing.

I had a girlfriend but I did not like her attitude, she began wandering around with men and did not respect herself, I preferred to stay without a girlfriend. I do not feel at risk, I do not wander around in whichever manner, if I do this and others hear about it, I will be ashamed of myself. I take care of my body, I never practiced evil behavior and feel embarrassed to embrace a woman.

—Male, 28, Unmarried, Village A

All mediating factors in the model motivated men and women in this study to reduce their risk regardless of their stance on gender disparities; however, there are some factors which can move in both directions (+/−). While men and women may be aware of their potential risk, other factors such as peers, emotional intimacy with a partner, relationship dynamics, past experience, education, income opportunities, and social, cultural, and gender norms influence whether individuals will remain complacent to this risk (−) or take action (+).

Even before HIV/AIDS came, I prevented wandering around with just anyone because I wanted to know if I got any diseases who infected me. I only follow with one, if he gives me support or not, I stay with him. I don’t know if I am at risk, when a man discovers a new woman they ignore the old one. We women do not like it when the man likes another one, but we are always afraid to inform them.

—Female, 29, Divorced, Village C

I have friends who have many girlfriends, today they are here tomorrow there. I just have one girlfriend, I like her a lot but have not had sex with her because she is still a virgin, when we reach an older age then we will get married. I never had another girlfriend before her, she is my first girlfriend, I do not have time to face women, I am just worried about my studies.

—Male, 21, Unmarried, Village A

I am happy with my boyfriend because he helps me a lot. The fear of him having other women is there but what to do, if I get HIV/AIDS then I get it, we don’t use a condom, it’s that proverb we say ‘you cannot eat a banana with the peel, it doesn’t have any taste’.

—Female, 40, Divorced, Village B

Components under mediating factors are interlinked, and in many cases, a combination is required to motivate men and women to take action, reinforcing the importance of factors beyond the individual level to be considered when responding to HIV. Importantly, the model accounts for some factors, particularly at the normative and structural level, that can move in either direction to maintain current risk levels or influence changes in behavior to reduce risk, such as when emotional intimacy can lead to risk reduction when love and trust are associated with protection, but can also maintain or increase risk when these same values lead individuals to abandon prevention methods.

I don’t feel at risk because I already know about HIV/AIDS and ways to prevent, I don’t know about my girlfriend but I trust she will not betray me with other people and get infected, that’s what my girlfriend says, we spoke of the disease, that we cannot sleep around in any manner if we don’t want to get it. I will have other girlfriends, it is not possible to only have this current one. I use condoms but not with my girlfriend, only when I am with other women.

—Male, 27, Unmarried, Village B

Peer influence can also be positive, such as when peers have multiple sexual partners and encourage others to abandon condoms with primary partners. Within relationship dynamics, the model accounts for how risk responses can influence individuals in both positive and negative ways through decision-making authority, ability to earn and control an income, and negotiating power.

She was my only girlfriend, but she behaved badly with my friend and for that I left her, I did not need to be contaminated, she can sleep with other people. Yes I always use a condom, there are other youth with girlfriends who say that I cannot use a condom with my principal girlfriend, that I should use condoms with other ladies or women, but I use it with all women.

—Male, 20, Unmarried, Village A

Under structural influences, access to education is a positive mediating factor in this study used to escape poverty and dependence on men for money. Access to income can also move in both directions since some men spend finances on sex outside of the marriage while others prefer to save their income to improve the lives of their family.

My wife works in the farm, even my girlfriend has a farm. When I have money, I give 20 meticais to my wife and 10 meticais I give to my girlfriend.

—Male, 37, Married, Village B

I can use a condom with women outside of my wife. I don’t use it at home because I have control with my wife, I use a condom only when I don’t know a woman’s behavior.

—Male Participant in Mixed Married Group, Village B

Social and cultural norms which shape gender roles can also move in either direction and can change over time. Social norms which tolerate wealth distribution from men to women through sexual encounters or cultural practices highlight different pathways through which risk can increase or decrease. Therefore, how men and women interpret and respond to each of the factors needs to be understood and applied to local contexts.

Risk assessment

Risk is contextualized based on influences at a multitude of levels which determine how individuals assess the severity of HIV and their own susceptibility. Findings confirm positions by AARM and the health belief model that individuals will not engage in risk reduction without accurate HIV knowledge. Men and women in this study believe that HIV exists and made an assessment of their potential risk levels based on their own or partner’s behavior.

With this one friend, we have not stayed together much time to learn about each other’s behavior, but he has still not shown me bad behavior. I see that he has good behavior even when something comes up he helps me. If he stops me from using a condom then he doesn’t like me, and I do not need him. When I tell him to use a condom he has to use because I don’t know where he has been.

—Female, 50, Widowed, Village C

Some factors at the structural and normative levels, as noted earlier, can move in either direction to maintain risk or motivate risk reduction. Gender, cultural, and social norms, which interact with other mediating factors in the model including relationship dynamics, peer influence, and access to education and income-generating opportunities, can profoundly influence the ability of men and women to change their behavior as a result of vested interests to comply with certain norms. For example, some women take minimal if any action in recognized risky relationships to avoid the socially hazardous single status. In other cases, women and men may be aware of potential HIV risk but deflect or deny this risk in order to secure greater resources or sexual pleasure.

In the beginning of the relationship we used a condom and after that he said I am the only one outside of his wife, and that he will not look for other women, he convinced me that he was only with me so we began to make love without condoms.

—Female, 29, Divorced, Village C

When I am not married I am very afraid, I no longer have protection and security, when the men arrive they stay for a time and then disappear. I need to marry, to stay without a man is hard.

—Female, 38, Divorced, Village C

Roles and expectations casting women and men into certain positions in society have a bearing on perceived risk. Consistent with gender and power theory, the ability of women to take action is often but not always constrained by differences in access to labor and opportunities. Economic dependence on men at times, limits women’s ability to act on perceived HIV risk to maintain finances for her and her family. Similarly, masculine norms are often linked to resource generation and provision, which in this study, is often used as a leverage to engage in sex with multiple women.

For a poor woman who is at home with nothing, the only way to support the family is having sex with a man. For the men, it is easy in relation to the women. For example I can stay two or three days without doing anything while for a woman she cannot because she does not have a home.

—Male, 27, Unmarried, Village B

It is because of poverty that women have many partners. If women stay from the morning to night or even two days without them or their children eating, of course they would go with a man who shows them money.

—Participant in Unmarried Female Group, Village A

They say that every man who has a high number of girlfriends is enjoying life and that we are the bosses because we have money, that’s why all the women like us, those who don’t have money are nothing.

—Participant in Married Male Group, Village A

Differences in economic opportunities between men and women influence responses to HIV risk. The resulting power imbalances such as lack of decision-making authority affect the ability of women to communicate safe sex with their partners even though they feel at risk, while among men who use their wealth to access sex, pleasure is often prioritized over potential HIV risk.

Women who marry early have an HIV risk. Their parents don’t understand that girls have not yet reached the age to marry, but they force her. You hear that someone is getting married instead of studying, which I see as a risk. For example, she is 10 or 12 years old, she is still in school and must be educated until she has reached a proper age to get married. If she marries early, she will not have knowledge of how to behave as a married person. If her husband goes to Pemba and starts wandering around with other women how will she take care of herself.

—Male, 35, Married, Village A

Married men are the bearers of this disease and the married women can do what they can to prevent. I am waiting for my husband and hope his behavior of seeing other women will decrease. I do not like how he treated me but I stay with him because I cannot be single.

—Female, 37, Married, Village D

However, in other cases, women who use sex for resources favor wealth over the health status of a man. According to gender and power theory, men who use their wealth to obtain sex from women are doing so to manifest their power. Yet, some women also use their bodies as a source of power to extract wealth from men.

There are women who accept to take the money from a man and be with him, then there appears a man with more money, they soon begin to follow this new man, then another one appears that has even more money than the first and second one, the women accepts to have sex with this new man and so on.

—Female, 23, Village B

Women pick up a man but they don’t know where he is from or even if he is infected, they are quickly conquered and then have sex. When finished, this woman does not go home, it is worse, she is looking for another man. These men also never ask the women where they were from or what they do, they just think of having sexual relations, that is why us women, we are the first to get disease because when we see money we don’t leave it.

—Female, 37, Married, Village D

Peer influence and social norms promoting sexual conquest among men or dictating the use of condoms in certain sexual encounters, such as “outside the house,” have a bearing on HIV risk or use of protection. For women, norms which discourage condom use in a marriage, affect their ability to negotiate safe sex encounters.

Condoms are used outside the house, at home with your husband it is not used. My husband always has other women. I try to speak with him but there is no understanding. I tell him that we have an HIV risk, but we still have sex without condoms because he is my husband.

—Female, 35, Married, Village B

I always explained to him that there are diseases. I can die, he can die and so can these women he is with. When I talked to my husband about it he told me to shut up, that I know nothing and that he is a man and knows everything.

—Female, 58, Divorced, Village D

There is a close relationship between how gender roles become maintained through certain social situations and HIV risk levels between men and women. Cultural, religious, and traditional norms that encourage polygyny and early marriage are viewed as particularly risky for women. This is not only in relation to HIV risk but linked to the limited ability of women to pursue education and income-generating opportunities to increase their agency and autonomy. Although poverty has a bearing on HIV risk, which is affected by income access and control between genders as noted by a systematic review in east, central, and southern Africa,38 the poor economic status of individuals across communities in the study setting resulted in minimal noted differences on risk or responses.

Mediating factors

Individual characteristics

Men and women who decide to act on perceived HIV risk feel it is within their control to take action in order to achieve desired outcomes (decreased risk). The factors that motivate individuals to enact change are based on a combination of normative influences, social learning, and structural components. For example, economic differences, leading to power imbalances can make it challenging for women to mitigate HIV risk; yet, some have made efforts to overcome this and leave a risky relationship as a result of self-efficacy but often also because of the need to secure a healthy life for the family.

I believed that he [former husband] had other women. When someone is bitten by a snake, every time they pass that route, they get frightened and think the same thing will happen. With this one [current husband], we live well, my heart is happy, I have not seen strange movements or bad behavior with him because for a man to treat you badly, he needs to discover another woman. I spoke to my husband about HIV and he says he can’t afford to have many women. When I am married, I like to stay with my husband only. I want to have children, but if I discover that he has many partners, I will make him use a condom. I prefer not to have children and take care of my health because he does not want children if this is how he behaves. If he doesn’t want to use a condom I will leave because I don’t know if the other women have partners besides my husband and then we end up getting a disease.

—Female, 34, Married, Village C

Similarly, men who choose not to allocate resources to extramarital partners, those who remain faithful, and others who use protection across all sexual encounters, are influenced by individual characteristics such as self-efficacy and self-regulation but also by observation of others, family influence, avoidance of diseases, concern for the family, and emotional intimacy with a partner.

My wife does not work, she is at home. I find and bring food home to eat from the farm. I am happy in my marriage, even though I do not have a job, my wife has never left me to marry another man. She has always been with me, it has been 10 years and I have not seen any bad behavior in her. That is a woman. I do not feel at risk, a lot of people admire that I do not have bad behavior, I am always with my wife and do not wander around in whichever form. I have not seen misbehavior on her part and she has also not seen bad behaviors on my part.

—Male, 35, Married, Village A

Normative influences

Derived from social cognitive theories, normative influences include those factors which help shape social or relationship norms. Peers, family advice and monitoring, emotional intimacy, and relationship dynamics are such normative influences and can affect the ability of individuals to reduce perceived HIV risk. As noted in previous studies, peer influence is usually grounded in prevailing gender and social norms, and can either have a positive39–43 or negative effect on health practices44–46 depending on an individual’s social networks. Some unmarried men in this study are questioning peer advice and behavior to engage in unprotected sex with multiple women. Instead, these men consider the consequences of taking on these behaviors in terms of their own HIV risk or the need to protect a primary partner and thus always use protection.

Most have many partners, here today if you have one girlfriend, tomorrow it is another. I have trust in one unique girlfriend so I don’t use a condom with her. I have not yet noticed any HIV/AIDS risk with her. When I am away and with other women, I use condoms in order to avoid diseases, whether it hurts or not I must use condoms so I do not infect my girlfriend, it is a form of prevention because I have responsibility.

—Male, 20, Unmarried, Village D

Parental and family influence has a very positive bearing on men and women to pursue less risky sexual situations as also noted in other studies from South Africa and the US.47–50 For men, the need to secure a sound future for their families by reserving rather than spending resources and the desire to maintain a good status in society are largely influenced by family advice or observation of others. Unmarried men are also influenced by observing parents who have remained monogamous, and abide by family advice to engage in condom use.

I have only one girlfriend but many of my friends have many girlfriends. Everyone deserves to have a girlfriend that you trust, I have only one girlfriend, she knows my secrets and I know hers. She is the one who I want to marry. My father did not have other women outside of my mother, and I now practice the advice that he gave me. He prohibited me from going out at night, it was either to work, study or sleep, I didn’t even go see films.

—Male, 22, Unmarried, Village C

Parental advice also plays a key role in influencing unmarried women to remain abstinent in order to prevent disease acquisition or complete school.

I fear HIV/AIDS but do not feel at risk because I have not yet started having sex with a man. If someday I meet a man who wants to have sex with me I will not accept it even if I love him, first we have to get married. With my husband, before marriage we must first go get tested to know our state of health, if he refuses to get an HIV test he will have to leave me. If he tells me something and I accept it and then if I say something to him and he refuses then how can we live? My mother always gives me moral strength to go to school and she says education is the future of tomorrow.

—Female, 15, Unmarried, Village A

Family support is also vital for women who want to leave risky relationships similar to findings from Malawi.51

My husband sold fish and was a carpenter, the little that he got he brought back for me, but then that turned into suffering, I began to see strange movements with him and realized that this is not a marriage. I felt HIV/AIDS risk with him because he was a womanizer, I was afraid to say anything because they say we can use condoms with women outside not inside the marriage. I also did not talk about condoms because he will say that I forced him to use a condom as if he is any ordinary man, not my husband. That’s why I don’t know what to say, I am limited and just follow his guidelines. When my father heard of this situation, he said it is better to leave so I went to my father’s house to live.

—Female, 35, Married, Village B

Emotional intimacy and relationship dynamics between partners can either exacerbate or decrease HIV risk, a finding which also corresponds to data from European surveys.52 Within relationship dynamics, an individual’s decision-making power over various household and sexual situations is influenced by the ability to earn an income and control resources in the household. Yet, there are instances where decision-making proved negligible and men and women still took measures to engage in HIV risk-reduction efforts because of family support, past experience and certain outcomes such as a respected social status.

In the first few days we started to sleep together, I went with this man to be examined in the hospital, we did an HIV test and it was negative. Always when I am with a man I go to the hospital to control my body. To have many men to help me, never, I do not need it, being with only one man is enough to get things that I cannot get, when you respect your body in your home you do not wander around in whichever manner. When I have a partner we stay together, people will never say that I change men, it has never been, I am a person of respect, I still have not had a disease.

—Female, 50, Widowed, Village C

In relation to emotional intimacy, some men and women feel at minimal risk because of trust, love, and care built with a partner over time. These individuals are confident that their partner would not betray them or do anything to harm their health. Other men and women use risk-reduction strategies to protect loved ones from the harmful consequences of HIV despite adhering to gender norms. Some unmarried men and women associate the acceptance of HIV risk-reduction methods by a partner as confirmation of love, trust, and care in the relationship with such actions providing vital insight into expectant behavior of a partner in the future.

When someone comes to ask me for relations and I accept, I first go for an HIV test. I already went to the hospital to get tested and I am in maximum condition with no infection. If a man comes and I do not know his behavior, I ask him to go to the hospital so we can do a test and know our health status. One day if I travel and leave my boyfriend, during the trip I can be with another man like he has done. When I return, we must go and get a test before we continue with our love. If he really loves me he will agree to get a test done, if not then he does not want me.

—Female, 45, Widowed, Village A

Structural influences

Structural influences include broad factors such as education, income, and social, cultural, and gender norms, which create enabling or constraining environments for individuals to enact change. Access to education and income-generating opportunities among women influences strategies to engage in HIV prevention and also affects measures to decrease perceived HIV risk. Some young unmarried women are determined to complete their education and will use this as a leverage to delay marriage, maintain financial autonomy, and demand an HIV test with a partner prior to marriage.

I have fear because I don’t know this disease, if one day I find a boyfriend and he doesn’t want to use a condom, I will leave him even if I like him because he is going to bring me diseases. If he is my husband I will talk to him to have one partner, if he refuses that is when I will leave him. I would like my husband to be my age and with a job, if the man accepts to marry me and lets me go to school I will marry him, if he doesn’t want me to study I will not marry that man.

—Female, 16, Unmarried, Village A

Some women take steps to survive through accepted forms of work, despite the easy money obtained through transactional sexual encounters, and do so to maintain self-respect and financial independence.

I think that if I don’t bother to go to the fields or work hard to get food, I’m going to suffer. I will not become a prostitute because I don’t deserve that, it is not a good thing, even if it is easy to get money, it doesn’t serve any purpose. If I wanted to I could have changed my behavior a long time ago, but I don’t want to get the diseases they get. Everyone is born with intelligence and ways of thinking, some do evil things and others think of ways to improve their lives, so each one has their own conscience.

—Female, 34, Married, Village C

Men generally have greater access to income and educational opportunities with some relying on their wealth to purchase sex from multiple women and others using their resources to improve their living standards and protect their family from HIV.

To say that I have a relationship with this money to get women, I cannot do this. I don’t need these women and I prefer to stay with my wife. I don’t want to look for another woman who will bring diseases from outside and through me it gets transmitted to my wife. If our child is born and he has this disease, I would feel very much about this, so I cannot do it.

—Male, 32, Married, Village C

Social learning

Based on cognitive theories, men and women take measures to reduce their risk often because of learning from social encounters and experiences. Alongside individual characteristics and structural and normative influences, men and women tend to engage in risk-reduction strategies because of a combination of their own past negative or high risk experiences, fear of disease acquisition based on prior STIs, and observing the behaviors of others. According to social learning theory, positive reinforcement and experiences motivate individuals to repeat successful behavior.20

I will not arrange money to go have other women, otherwise I will struggle to raise my children, that will not happen. Having a woman outside doesn’t give you confidence, because you give money to her and each one goes their own way. My father was always telling me about the diseases, he said I must not have sex in any manner to avoid getting sexually transmitted diseases. I followed what he said and he was not lying because I was seeing it.

—Male, 27, Unmarried, Village B

However, this study also found that negative experiences (STI acquisition or an unfaithful partner) can lead individuals to rethink future action including more careful partner selection and condom use with subsequent partners in order to reach desired positive outcomes such as decreased HIV risk.

I think that a woman knows how to take care but the man increases the disease, he cannot hold onto and support only one woman. When you have women with no power to talk, they practice sexual relations in any manner, these days we do not have value because we don’t have money, we depend on men. To stay without a man is tough in this village. I go to the farm, produce something to sell and do my business. With my first husband, he did not consider me well, he had other woman and I didn’t like that so I left. I feel embarrassed when I ask for condoms, sometimes the nurses wonder why an older women like me uses it. I keep them and wait for my partner to arrive and inform him that I was able to get condoms to use so we can avoid disease and unwanted pregnancies, then I tell him that without condoms you are not able to be with me, if he understands we will use it, if he refuses he can leave. I do not need to see or speak with someone who doesn’t use condoms because I know that it brings conflicts on the part of health and he doesn’t want to hear the decision of the woman, this type of person is never good.

—Female, 38, Divorced, Village C

Outcomes

Risk assessment and the decision to modify behaviors are intimately linked to broader outcomes which not only influence HIV risk-reduction strategies, but take into consideration other factors. In some instances, the focus on broader outcomes may hold more intrinsic value than the reduction in HIV risk. For example, men who do not provide finances to other women in exchange for sex may do so primarily to save money and ensure their family’s well-being with potential mitigation of HIV risk a secondary benefit.

My children and wife depend on me, the little that I have is to give to my family. For many years, I did not have enough money, now I do not see the reason to abandon my children and my wife and look for misery. I do not want this life. I remember when my grandfather was alive, he said that in the world you will never hear that a man has luck for having more than three women. It is nothing more than an illusion, you do not gain anything, on the contrary, you will waste it and have more expenses. He said it is good to just have and support one wife, which I do.

—Male, 28, Married, Village C

Similarly, some women who do not exchange sex for resources may be motivated by wanting to maintain a good social status rather than out of direct fear of HIV.

Here it is easy to get money without doing prostitution, but a lot of people don’t think of it. It is easy for a woman, she can go and fetch firewood, bring it here and sell it to get money. I do this to create a means of living. I have never asked for help from anyone, sometimes I didn’t have anything but I didn’t suffer. For me to do farming was because of my father. Since I didn’t have the opportunity to study, he said I should have my own farm to be like those who studied and feed myself, so I followed his advice.

—Female, 45, Married, Village D

Discussion: Policy and Program Implications

The experiences of positive deviant cases in this study provided insight into the factors influencing risk-reduction practices among a unique sub-group of men and women, regardless of their views on gender norms. The extent to which positive deviant behavior can successfully be replicated beyond the study setting appears promising given that it draws on the experiences of individuals living in the same conditions (ie gender norms and poverty) as other community members, yet barriers have been overcome to reduce HIV risks. Such experiences, therefore, may resonate with men and women in surrounding areas. Positive deviant cases, or those men and women who take measures to reduce their perceived HIV risk regardless of often gender imbalanced norms and social views in this study, are all influenced by a common set of factors noted in the HARAR model including: individual characteristics, family advice and support, observation, learning from past experiences, fear of the infection, the need to protect oneself, a partner or children, the association of risk-reduction strategies with emotional intimacy, and the desire to maintain a good social standing. These drivers of positive behavior could be incorporated into localized HIV responses and build on the specific ways men and women engage in risk reduction.

When designing HIV prevention programs, mediating factors that move in either direction should be carefully considered, with emphasis placed on factors indicating strong positive tendencies toward risk reduction. For example, the association between emotional intimacy and a partner’s acceptance of risk-reduction strategies indicates a shift in norms on safe sexual behavior, which should be focused on in prevention campaigns. There are some factors at the normative and social learning level that are specific to individual cases such as relationship dynamics, family advice, past experience, and observation, which in turn affect both risk and risk reduction. Recognizing how such factors influence behavior modification toward reduced risk should broaden their use including through the sharing of individual experiences with others via peer to peer approaches, and engaging in dialog on how these experiences can be applied to other peoples’ situations through modeling the positive behavior of families or couples. In the policy realm, mediating factors which indicate a strong push to behavior modification, such as access to education (which can in turn affect a women’s negotiating power over safe sex or access to income) or social support services for women wanting to leave risky relationships should be promoted. Complementing this, concerted efforts should also be placed on linking risk reduction with other broad outcomes salient to the population such as “containing income and resources” for the family’s protection and financial well-being.

Conclusion

The HARAR model can be adapted to different settings in order to help curb HIV risk among women living in rural areas. Since gender norms are not static, but rather in constant flux, the ability of men and women to work within and challenge these norms to reduce HIV risk needs to be understood and included into programs and policies. Although in some cases, gender norms which balance out disparities between men and women may heighten HIV risk, efforts should continue to promote gender equality in its own right and as a means to facilitate HIV risk reduction among men and women. Building on what men and women already do to reduce their risk will aid program and policy initiatives in different settings as HIV responses will be grounded in local contexts and social situations.

Acknowledgments

This research would not have been possible without financial support from the Gordon Smith Travelling Scholarship of the Wellcome Trust. The author thanks all the research respondents for agreeing to participate and sharing their intimate experiences with us as well as the research team for the valuable support provided. Gratitude is also extended to all staff at the host institution for accommodating the research.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Conceived the experiments: SB. Analyzed the data: SB. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: SB. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: SB. Agree with manuscript results and conclusions: SB. Jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper: SB. Made critical revisions and approved final version: SB. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

ACADEMIC EDITOR: Goberdhan P. Dimri, Editor in Chief

FUNDING: Author discloses no funding sources.

COMPETING INTERESTS: Author discloses no potential conflicts of interest.

This paper was subject to independent, expert peer review by a minimum of two blind peer reviewers. All editorial decisions were made by the independent academic editor. All authors have provided signed confirmation of their compliance with ethical and legal obligations including (but not limited to) use of any copyrighted material, compliance with ICMJE authorship and competing interests disclosure guidelines and, where applicable, compliance with legal and ethical guidelines on human and animal research participants. Provenance: the authors were invited to submit this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shisana O, Davids A. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2004. Correcting gender inequalities is central to controlling HIV/AIDS; p. 812. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta GR. How men’s power over women fuels the HIV epidemic. Br Med J. 2002;324(7331):183–184. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7331.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim JC, Watts CH. Gaining a foothold: tackling poverty, gender inequality, and HIV in Africa. Br Med J. 2005;331(7519):769–772. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7519.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shisana O. Gender and HIV/AIDS: focus on Southern Africa; Paper presented at: International Institute on Gender and HIV/AIDS; 2004; South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta GR, Whelan D, Allendorf K. Integrating Gender into HIV/AIDS Programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turmen T. Gender and HIV/AIDS. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2003;82(3):411–418. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(03)00202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.UNAIDS . Gender and HIV/AIDS: Taking Stock of Research and Programmes. Geneva: UNAIDS; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connell R. Gender and Power. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Instituto Nacional de Estatistica . Census 2007. Mozambique: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hochfeld T, Bassadien SR. Participation, values, and implementation: three research challenges in developing gender-sensitive indicators. Gend Dev. 2007;15(2):217–230. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marsh DR, Schroeder DG, Dearden KA, Sternin J, Sternin M. The power of positive deviance. Br Med J. 2004;329(7475):1177–1179. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7475.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marsh DR, Schroeder DG. The positive deviance approach to improve health outcomes: experience and evidence from the field: preface. Food Nutr Bull. 2002;23(suppl 4):5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mackintosh UA, Marsh DR, Schroeder DG. Sustained positive deviant child care practices and their effects on child growth in Viet Nam. Food Nutr Bull. 2002;23(4 suppl):18–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dearden KA, Quan Le N, Do M. Work outside the home is the primary barrier to exclusive breastfeeding in rural Viet Nam: insights from mothers who exclusively breastfed and worked. Food Nutr Bull. 2002;23(4 suppl):101–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahrari M, Kuttab A, Khamis S, et al. Factors associated with successful pregnancy outcomes in upper Egypt: a positive deviance inquiry. Food Nutr Bull. 2002;23(1):83–88. doi: 10.1177/156482650202300111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Standard Demographic and Health Survey . Instituto Nacional de Estatistica, Ministerio da Saude, ORC Macro, DHS Program. Mozambique: 2003 Standard Demographic and Health Survey; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strauss AI, Corbin K. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flay B, Petraitus J. The theory of triadic influence: a new theory of health behaviour with implications for prevention interventions. In: Albrecht G, editor. Advances in Medical Sociology, Vol. 1V: A Reconsideration of Models of Behaviour Change. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1994. pp. 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bandura A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Catania JA, Kegeles SM, Coates TJ. Towards an understanding of risk behavior: an AIDS risk reduction model (ARRM) Health Educ Q. 1990;17(1):53–72. doi: 10.1177/109019819001700107. [Spring] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maiman LA, Becker MH. The health belief model: origins and correlates in psychological theory. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2:336–353. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of human development. In: Husen T, Postlethwaite TN, editors. International Encyclopedia of Education. 2nd ed. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1996. pp. 5513–5518. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pajares F. Overview of Social Cognitive Theory and of Self-Efficacy. 2002. [Accessed December 2006]. Available at http://www.emory.edu/EDUCATION/mfp/eff.html.

- 25.DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, Crosby RA, Rosenthal SL. Prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections among adolescents: the importance of a socio-ecological perspective—a commentary. Public Health. 2005;119:825–836. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Latkin CA, Knowlton AR. Micro-social structural approaches to HIV prevention: a social ecological perspective. AIDS Care. 2005;17(suppl 1):S102–S113. doi: 10.1080/09540120500121185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Voisin DR, DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, Crosby RA, Yarber WL. Ecological factors associated with STD risk behaviors among detained female adolescents. Soc Work. 2006;51(1):71–79. doi: 10.1093/sw/51.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roura M, Busza J, Wringe A, Mbata D, Urassa M, Zaba B. Barriers to sustaining antiretroviral treatment in Kisesa, Tanzania: a follow-up study to understand attrition from the antiretroviral program. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(3):203–210. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becker MH, Haefner DP, Kasl SV, Kirscht JP, Maiman LA, Rosenstock RM. Selected psychosocial models and correlates of individual health-related behaviors. Med Care. 1977;15(5):27–46. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197705001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Becker MH. The health belief model and personal health behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2:336–353. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biddle BJ. Recent development in role theory. Annu Rev Sociol. 1986;12:67–92. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomkins S. Part IV Script theory: The differential magnification of affect. In: Demos E Virginia., editor. Exploring Affect: The Selected Writings of Silvan S. Tomkins. Cambridge: Press Syndicate University of Cambridge; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore HL. A Passion for Difference: Essays in Anthropology and Gender. Cambridge: Indiana University Press and Polity Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore HL. The Subject of Anthropology: Gender, Symbolism and Psychoanalysis. Cambridge: Polity Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Beauvoir S. The Second Sex. New York: Knopf Inc; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weeks J. Sexuality. 2nd ed. London: Routledge; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foucault R. The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction. New York: Random House Inc; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wojcicki JM. Socioeconomic status as a risk factor for HIV infection in women in east, central and southern Africa: a systematic review. J Biosoc Sci. 2005;37:1–36. doi: 10.1017/s0021932004006534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Norr KF, Norr JL, McElmurry BJ, Tlou S, Moeti MR. Impact of peer group education on HIV prevention among women in Botswana. Health Care Women Int. 2004;25(3):210–226. doi: 10.1080/07399330490272723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karim AM, Magnani RJ, Morgan GT, Bond KC. Reproductive health risk and protective factors among unmarried youth in Ghana. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2003;29(1):14–24. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.29.014.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith D, Roofe M, Ehiri J, Campbell-Forrester S, Jolly C, Jolly P. Sociocultural contexts of adolescent sexual behavior in rural Hanover, Jamaica. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33:41–48. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00563-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boyer CB, Shafer M, Wibbelsman CJ, Seeberg D, Teitle E, Lovell N. Associations of sociodemographic, psychosocial, and behavioral factors with sexual risk and sexually transmitted diseases in teen clinic patients. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27:102–111. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agha S. An evaluation of the effectiveness of a peer sexual health intervention among secondary-school students in Zambia. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14:269–281. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.5.269.23875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phaladze N, Tlou S. Gender and HIV/AIDS in Botswana: a focus on inequalities and discrimination. Gend Dev. 2006;14(1):23–35. [Google Scholar]

- 45.MacPhail C, Campbell C. ‘I think condoms are good but, aai, I hate those things’: Condom use among adolescents and young people in a Southern African township. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(11):1613–1627. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Millstein SG, Moscicki A. Sexually transmitted disease in female adolescents: effects of psychosocial factors and high risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 1995;17:83–90. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00065-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petersen I, Bhana A, McKay M. Sexual violence and youth in South Africa: the need for community-based prevention interventions. Child Abuse Neglect. 2005;29(11):1233–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dageid W, Duckert F. Balancing between normality and social death: Black, rural, South African women coping with HIV/AIDS. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(2):182–195. doi: 10.1177/1049732307312070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Crosby R, Cobb BK, Harrington K, Davies SL. Parent-adolescent communication and sexual risk behaviors among African American adolescent females. J Pediatr. 2001;139(3):407–412. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.117075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dilorio C, Kelley M, Hockenberry-Eaton M. Communication about sexual issues: mothers, fathers, and friends. J Adolesc Health. 1999;24:181–189. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schatz E. Take your mat and go!’: rural Malawian women’s strategies in the HIV/AIDS era. Cult Health Sex. 2005;7(5):479–492. doi: 10.1080/13691050500151255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bajos N. Social factors and the process of risk construction in HIV sexual transmission. AIDS Care. 1997;9(2):227–238. doi: 10.1080/09540129750125244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]