Abstract

Many animals thrive when given a choice of separate sources of macronutrients. How they do this is unknown. Here, we report some studies comparing the spontaneous choices between carbohydrate-and fat-containing food sources of seven inbred mouse strains (B6, BTBR, CBA, JF1, NZW, PWD and PWK) and three mouse models with genetic ablation of taste transduction components (T1R3, ITPR3 and CALHM1). For 8 days, each mouse could choose between sources of carbohydrate (CHO-P; sucrose-corn-starch) and fat (Fat-P; vegetable shortening) with each source also containing protein (casein). We found that the B6 and PWK strains markedly preferred the CHO-P diet to the Fat-P diet, the BTBR and JF1 strains markedly preferred the Fat-P diet to the CHO-P diet, and the CBA, NZW and PWD strains showed equal intakes of the two diets (by weight). Relative to their WT littermates, ITPR3 and CALHM1 KO mice had elevated Fat-P preferences but T1R3 KO mice did not. There were differences among strains in adaption to the diet choice and there were differences in response between males and females on some days. These results demonstrate the diverse responses to macronutrients of inbred mice and they point to the involvement of chemosensory detectors (but not sweetness) as contributors to macronutrient selection.

Index terms: Mouse strain survey, food choice, gustation, fat preference

1. Introduction

Animals thrive when given appropriate choices of macronutrients to select from (1). How they do this is unknown. There have been several attempts to understand the physiological controls underlying macronutrient selection [e.g., (2–7)] and to assess environmental and behavioral contributions [e.g., (3,8) ; reviews (7,9,10)], but there has been very little effort to characterize the genetic controls. Smith Richards and colleagues found diverse preferences among 13 strains of mice allowed to choose from separate sources of protein, carbohydrate and fat (11). Based on a B6×CAST F2 intercross, they discovered three chromosomal regions linked to macronutrient preference (12) and characterized one, a locus on chromosome 17, in detail (12–15). We demonstrated that a 21-gene region of chromosome 17 influenced macronutrient selection (16) and hypothesized that the causative gene was Itpr3, a component of the canonical G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) taste transduction cascade.

Here, we used the two-cup choice method developed by Smith Richards et al (11) to investigate the selection of carbohydrate and fat by 7 mouse strains. We also took advantage of three knockout (KO) mouse models, involving genetic ablation of T1R3, ITPR3, and CALHM1, to investigate the contribution of these taste transduction elements to macronutrient choice.

2. Methods

We conducted four experiments, which all used the same general test procedures. One experiment compared 7 inbred mouse strains; each of the other three compared mice with a genetic ablation of a taste-related gene to their wild-type (WT) controls. All procedures were approved by the Monell Chemical Senses Center Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.1. Subjects

The largest experiment compared 7 inbred mouse strains, with the following names, abbreviations, and Jackson Lab stock numbers: C57BL/6J (B6; 000664), BTBR T+ Itpr3tf/J (BTBR; 002282), CBA/J (CBA), JF1/Ms (JF1; 003720), NZW/LacJ (NZW; 001058), PWD/PhJ (PWD; 004660), PWK/PhJ (PWK; 003715). The mice were the progeny of founders obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (JAX). The JF1 mice originated from stock provided to us in 2001 (12 years ago; before access to these mice was restricted) so they have had many generations to diverge from the JF1/Ms strain and are best considered as a distinct strain, JF1/MsMon. The other mice tested were 1 – 3 generations descendant from the purchased founders, which allowed little opportunity for genetic drift. The strains were chosen for study because they have wide phylogenetic diversity (17,18) and were conveniently available in our laboratory because of our interest in calcium taste. The BTBR, JF1, PWD and PWK strains have anomalously high preferences for calcium [relative to 37 other strains (19); see Mouse Phenome Project (20)]; the B6, CBA and NZW strains avoid calcium. We have tested the macronutrient preferences of the BTBR and NZW strains previously (16); Smith Richards and colleagues have previously tested B6 mice and another 12 strains (11–13), which were not tested here.

We conducted three experiments involving mice with genetic ablation of the taste-related genes, Tas1r3, Itpr3, and Calhm1. The T1R3 KO mice were provided to us in 2007 by Dr. R. Margolskee (now at Monell), the ITPR3 KO mice were made by us in 2012 according to procedures described elsewhere (21). The CALHM1 KO mice were from stock provided in 2013 by Dr. Kevin Foskett (University of Pennsylvania) which, in turn, were from stock generated by Dr. Philippe Marambaud [Feinstein Institute for Medical Research; (22,23)]. Each KO mouse line was backcrossed to the B6 strain for several generations and then maintained by crossing heterozygotes (+/−) so that homozygous wild-type (WT; +/+) and knockout (KO; −/−) mice could be obtained from the same litter. Genotypes were determined by a commercial assay service (Transnetyx, Inc). Heterozygotes were not tested (they were needed to breed mice for other experiments).

2.2. Test Procedures

The mice were housed in a vivarium maintained at 23°C with a 12:12 h light/dark cycle (lights off at 1900 h). They were weaned at 21 – 23 days and raised in groups of the same sex until ~7 days before testing, when they were individually housed in plastic “tub” cages (dimensions, 26.5 × 17 × 12 cm) with 5 – 10 mm pine shavings on the floor. Deionized water was available to drink from a 300-mL glass bottle with a stainless steel sipper tube, and the maintenance diet, pelleted AIN-76A (Dyets Inc, Bethlehem, PA; catalogue no. 100000) was available to eat from a hopper built into the cage lid.

At the start of the 8-day test, each mouse was housed in a new cage with two glass jars (30-mL capacity; Fisherbrand, catalog no. 02-911-912) holding the diets described in Table 1. The distinctive feature of the CHO-P diet was that it contained corn starch and powdered sucrose, whereas the Fat-P diet contained vegetable shortening. Both diets contained casein (protein), minerals and vitamins. The diets were placed in the cage, with the CHO-P diet on the left and the Fat-P diet on the right. To prevent the two jars being knocked over, each was held upright in the center of a 3” diameter acrylic disk (U.S. Plastics Corp., catalogue no. 44185) by three clear 8–32” × 7/8” screw fasteners (U.S. Plastics Corp., catalogue no. 32016). Food spillage using these jars was minimal but any spillage was easily collected from the acrylic disk and was accounted for. In addition, the cage had a corrugated cardboard sheet on the floor (instead of pine shavings) to allow detection and collection of any far-flung spillage. Every 24 h, the food jars and spillage were weighed with 0.1-g precision and the positions of the two jars were switched. In order to maintain freshness, the Fat-P diet was replaced every other day and refilled on alternate days; the CHO-P diet was refilled as needed. Body weights were measured daily to the nearest 0.1 g.

Table 1.

Composition of carbohydrate-and-protein (CHO-P) and fat-and-protein (Fat-P) diets given as a choice to congenic mice

| Ingredient | CHO-P diet |

Fat-P diet |

|---|---|---|

| Casein, g/kg | 198.8 | 327.7 |

| DL-Methionine, g/kg | 2.9 | 4.9 |

| Sucrose, powdered, g/kg | 212.4 | 0.0 |

| Cornstarch, g/kg | 496.2 | 0.0 |

| Primex (vegetable shortening), g/kg | 0.0 | 519.3 |

| Cellulose, g/kg | 49.2 | 76.2 |

| AIN-76A Mineral Mix #200000, g/kg | 32.0 | 53.3 |

| AIN-76A Vitamin Mix #300050, g/kg | 10.0 | 15.3 |

| Choline chloride, g/kg | 1.8 | 3.1 |

| Energy content, kcal/g | 3.41 | 5.95 |

| % protein | 20.8 | 19.7 |

| % CHO | 79.2 | 1.8 |

| % fat | 0 | 78.5 |

Notes: Values are in g/kg diet. The small percentage of CHO in the Fat-P diet derives from sucrose used as the diluent for the DL-methionine, mineral and vitamin mixes. The diets were prepared by Dyets Inc, Bethlehem, PA (catalogue no. 103259 and 103260).

Because of limited equipment and difficulty breeding the mice, experiments were conducted in replications of 20 – 24 mice. The mice had a wide age range (albeit all adult; Table 2) but care was taken to test cohorts of the same age and, for the KO experiments, WT and KO mice from the same litters. Table 2 summarizes the number, sex, age and body weight of the mice.

Table 2.

Summary of number, age, and weight of mice tested

| Males | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | n | age range, d |

weight, g |

n | age range, d |

weight, g |

| B6 | 9 | 80–114 | 33 ± 1 | 9 | 106 | 20 ± 1 |

| BTBR | 11 | 97–128 | 39 ± 1 | 11 | 87–182 | 30 ± 1 |

| CBA | 8 | 90–101 | 27 ± 1 | 8 | 81–139 | 21 ± 1 |

| JF1 | 9 | 62–172 | 23 ± 2 | 8 | 63–105 | 13 ± 0 |

| NZW | 11 | 72 | 30 ± 0 | 12 | 62 | 25 ± 1 |

| PWD | 8 | 192 | 20 ± 0 | 10 | 91–147 | 14 ± 0 |

| PWK | 8 | 62–164 | 16 ± 1 | 10 | 77–100 | 13 ± 0 |

| T1R3 WT | 8 | 51–58 | 23 ± 1 | 5 | 51–58 | 18 ± 1 |

| T1R3 KO | 5 | 51–58 | 19 ± 2 | 7 | 51–58 | 21 ± 2 |

| ITPR3 WT | 8 | 68–113 | 25 ± 1 | 19 | 68–194 | 24 ± 1 |

| ITPR3 KO | 8 | 83–99 | 28 ± 2 | 19 | 74–194 | 23 ± 1 |

| CALHM1 WT | 6 | 58–116 | 21 ± 1 | 8 | 58–116 | 19 ± 1 |

| CALHM1 KO | 6 | 58 | 23 ± 0 | 4 | 58–116 | 20 ± 1 |

Notes: age range gives youngest – oldest (in days); when only one value is given all mice were the same age.

2.3. Data analysis

The primary measures of each experiment were daily intakes of CHO-P diet and Fat-P diet. Preference for the Fat-P diet was derived in two ways: Preferences by weight were calculated as the ratio of Fat-P intake (in g) divided by total intake [in g; i.e., Fat-P intake/(Fat-P intake + CHO-P intake) × 100]. Preferences by energy were calculated using the same formula after weights (in g) were converted to kilocalories based on an energy density of 3.41 kcal/g for the CHO-P diet and 5.95 kcal/g for the Fat-P diet.

Intakes of each diet (in g), total intakes (in kcal), and Fat-P diet preferences were analyzed using mixed-design ANOVAs with factors of Group (i.e., strain or genotype), Sex and Day. Post hoc LSD tests were used to compare intakes of the groups on individual days when an interaction term was significant. The criterion for statistical significance was p < 0.01.

3. Results

3.1. Macronutrient choices of 7 inbred strains

Omnibus ANOVAs of the results of the inbred strain comparison experiment produced many significant main effects and interactions, including three-way interactions of Strain × Sex × Day (Supplementary Table S1). To simplify, separate two-way ANOVAs (Sex × Day) for each strain were conducted (Supplementary Table S2). These revealed that there were no main effects of Sex on any measure except for Fat-P intake and total energy intake of the PWD strain. Consequently, here we describe the results of both sexes combined. The Sex × Day interactions are depicted in supplementary material (Figure S1).

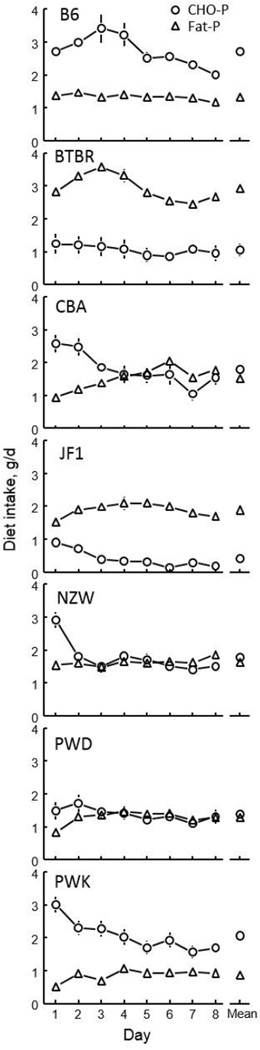

The B6 and PWK strains ate persistently more CHO-P diet than Fat-P diet throughout the 8-day test, although the differences became smaller as the test progressed (Fig. 1). The CBA, NZW and PWD strains ate significantly more CHO-P diet than Fat-P diet on the first day or first two days of the test but this dissipated so that there were no longer significantly differences after the 2nd or 3rd day. In marked contrast, the BTBR and JF1 strains ate significantly more Fat-P than CHO-P diet throughout the test (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Based on diet weight, the CBA, NZW, and PWD strains were indifferent to the Fat-P diet, the BTBR and JF1 strains preferred it, and the B6 and PWK strains avoided it (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Consumption of diets containing carbohydrate-and-protein (CHO-P) and fat-and-protein (Fat-P) during 8-day choice tests by 7 strains of mice.

Table 3.

Measures of daily food consumption averaged over the 8-day macronutrient choice test

| Strain | n | CHO-P intake, g |

Fat-P intake, g |

Total intake, kcal |

Fat-P preference by weight, % |

Fat-P preference by energy, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B6 | 18 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.11 | 17 ± 1 | 34 ± 13 | 47 ± 1 |

| BTBR | 22 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.11 | 21 ± 0 | 77 ± 43 | 84 ± 33 |

| CBA | 16 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 15 ± 0 | 49 ± 4 | 60 ± 33 |

| JF1 | 17 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 1.9 ± 0.11 | 13 ± 1 | 83 ± 23 | 89 ± 13 |

| NZW | 23 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.11 | 16 ± 0 | 45 ± 4 | 57 ± 43 |

| PWD | 17 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 12 ± 0 | 51 ± 5 | 61 ± 43 |

| PWK | 14 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.11 | 12 ± 0 | 31 ± 33 | 41 ± 43 |

| T1R3 WT | 13 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 15 ± 0 | 53 ± 5 | 64 ± 43 |

| T1R3 KO | 12 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 15 ± 1 | 62 ± 73 | 70 ± 63 |

| ITPR3 WT | 27 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 15 ± 0 | 55 ± 4 | 65 ± 43 |

| ITPR3 KO | 27 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.11 | 16 ± 0 | 70 ± 42, 3 | 78 ± 42. 3 |

| CALHM1 WT | 14 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 15 ± 0 | 47 ± 6 | 58 ± 53 |

| CALHM1 KO | 10 | 0.6 ± 0.12 | 2.3 ± 0.11,2 | 16 ± 1 | 82 ± 22, 3 | 88 ± 22, 3 |

Notes: Values are means ± SEs based on daily averages of 8-day tests, including males and females combined.

p<0.01 relative to intake of CHO-P diet.

p<0.01 relative to wild-type (WT) controls.

p<0.01 relative to indifference (50% preference, according to one-sample t-tests).

There were marked differences among the strains in total energy consumption. The BTBR strain consumed significantly more calories than did the B6, CBA and NZW strains, which in turn consumed significantly more calories than did the JF1, PWD and PWK strains. Based on energy content, the B6 strain was indifferent to the Fat-P diet, the BTBR, CBA, JF1, NZW and PWD strains preferred it, and only the PWK strain avoided it (Table 3).

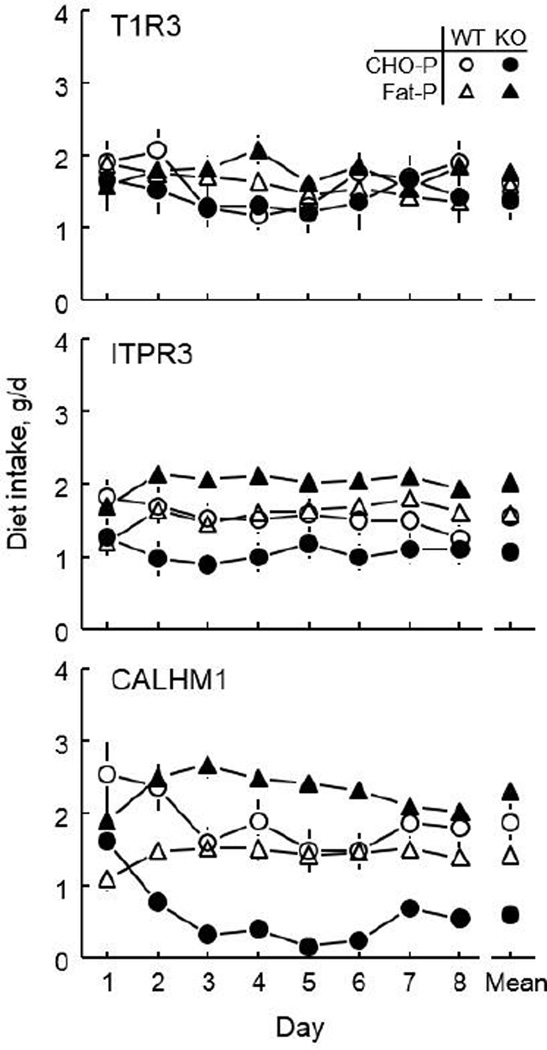

3.2. Influence of taste-related gene knockout on macronutrient choice

In each of the three experiments involving taste-related KO mice, the WT controls ate similar weights of CHO-P and Fat-P diet (except for the ITPR3 WT mice on Day 1 and the CALHM1 WT mice on Day 1 and 2, when these groups ate more CHO-P diet than Fat-P diet). The T1R3 KO mice did not differ from their WT controls in any measure: CHO-P diet intake, Fat-P diet intake, total energy intake, or either form of Fat-P preference score (Table 3 and Table S2). The ITPR3 KO mice did not differ from their WT controls in intake of CHO-P diet, Fat-P diet or energy, but the ITPR3 KOs had significantly higher weight-based and energy-based Fat-P preference scores. Finally, the CALHM1 KOs ate significantly less CHO-P diet and significantly more Fat-P diet than did their WT controls, leading to considerably greater Fat-P preferences in the CALHM1 KO group. Remarkably, between Day 3 and 6 of the test, the CALHM1 KO mice consumed virtually all their food as Fat-P and none as CHO-P. Despite this, these two groups did not differ in energy intake at any time.

4. Discussion

4.1. Differences among strains in macronutrient choice

Our strain survey, albeit small, revealed substantial diversity among strains in the choice between sources of carbohydrate and fat. Based on food weight, the CBA, NZW and PWD strains ate roughly equal amounts of each diet, the B6 and PWK strains ate roughly double the CHO-P diet than Fat-P diet, and the BTBR and JF1 strains ate roughly four times more Fat-P diet than CHO-P diet. It is tempting to conclude that the B6 and PWK strains are “carbohydrate-likers” and the BTBR and JF1 strains are “fat-likers” but this assumes that food weight is the pertinent factor being regulated. If the pertinent factor is energy consumption then the higher energy content of the Fat-P diet than CHO-P diet biases preference ratios toward the fat source, such that the B6 and PWK strains appear indifferent, and the CBA, NZW, and PWD strains moderately prefer the fat source to the carbohydrate source. Whether weight or energy, the BTBR and JF1 are strong fat likers.

It is beyond the scope of this paper to identify the mechanisms underlying these strain differences but it is tempting to speculate. Both of the fat-preferring (or carbohydrate-avoiding) mouse strains, BTBR and JF1, are prone to obesity and diabetes. JF1 mice fed high-fat diet develop early-onset type 2 diabetes and obesity, and were ranked the fattest out of 40 mouse strains tested when fed AIN-76A diet (24). BTBR mice are prone to insulin resistance and abdominal obesity (25). Thus, difficulties in utilizing carbohydrates may contribute to the strong Fat-P preference demonstrated by the JF1 and BTBR strains, just as diabetic rats avoid the diet previously associated with a glucose load (26) and choose a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet (27).

BTBR mice, in addition to having potential difficulties utilizing CHO-P diet, may not find its taste as palatable as did the other strains tested here: The BTBR strain has a mutation that disrupts its ability to transduce GPCR-mediated tastes [including sweet, umami and bitter (21)]. There are no published reports of the taste sensitivity of the JF1 strain, although our unpublished work suggests it has relatively normal avidity for sweet solutions and avoidance of bitter solutions in two-bottle choice tests.

Mean strain macronutrient intakes during the last 6 days of the 8-day test were remarkably stable (Fig. 1). However, the initial response to the diet choice differed among the strains. The CBA, NZW and PWK strains strongly preferred the CHO-P diet to the Fat-P diet during the first day, but this avidity for carbohydrate dissipated over the next day or two. This could reflect adaptation to the diet and learning about its metabolic consequences. However, the other strains showed more-or-less constant carbohydrate and fat choices throughout the test; there was no evidence that the B6, BTBR, JF1 or PWD strains needed to adapt to the diets or learn about them.

The initial preference for CHO-P diet of the majority of the mouse strains tested here is in line with our earlier finding that prior experience with a carbohydrate-rich food source biases subsequent macronutrient selection in favor of carbohydrate-rich food (28): This is because the regular maintenance diet the mice were fed was AIN-76A diet, which provides 68% of energy in the form of carbohydrates, a proportion not dissimilar to the 79% carbohydrate supplied by CHO-P diet. In other words, most mice may have first selected what was familiar to them. The fact that BTBR and JF1 mice did not suggests that they were either unable to recognize the familiar food source or actively avoided it.

The complex interactions between strain, sex and test day we obtained most likely reflect underlying hormonal and environmental factors that interact with genotype. It is also likely that some of these effects result from Type II statistical errors due to a lack of power. We note that the strain mean values we obtained are, as far as we can tell, robust (i.e., replicable). Our finding that B6 mice have a 47 ± 1% Fat-P preference (by energy) compares closely to the values of 53 ± 3% (12) or 52% (13) obtained by Smith Richards and colleagues, who used similar macronutrient sources and procedures to ours, but a 10-day choice test. Similarly, our Fat-P preference values of 84 ± 3% for BTBR mice and 57 ± 4% for NZW mice compare closely to values of 85 ± 3% and 60 ± 3% from our previous work with these two strains (16). Thus, there is reason to believe that the results from inbred strains are replicable, even across laboratories which suggests genetic factors may outweigh environmental factors for this phenotype [see (29)].

4.2. Influence of taste-related gene knockout on macronutrient choice

The CHO-P versus Fat-P choice test is complex. Each nutrient source has several attributes that could potentially influence selection, including nutrient density, digestibility, osmolarity and sensory characteristics. As a preliminary foray to investigate the role of taste as a factor influencing nutrient selection, we examined mice with three genetic ablations that influence taste transduction: T1R3, ITPR3 and CALHM1. T1R3 is a GPCR subunit required for the detection of sweet, umami, calcium and ethanol [e.g., (30–36)]. Stimulation of taste-related GPCRs including T1R3 and other T1R and T2R family members activates G proteins that foster the production of inositol trisphosphate (IP3). IP3 acts on the inositol trisphosphate receptor type 3 (ITPR3) to release calcium from endoplasmic reticulum. The ITPR3-gated elevation of cytosolic calcium activates TRPM5 cation channels, which allow sodium to enter the taste cell, causing membrane depolarization and the initiation of action potentials. In response to this, channels formed from calcium homeostasis modulator 1 (CALHM1) subunits allow ATP to escape from the taste cell. The ATP acts as a neurotransmitter to stimulate receptors on nerves that convey taste information to the brain. Consequently, both ITPR3 KO and CALHM1 KO mice are indifferent to tastes detected by GPCRs, including sweet, bitter, Polycose and calcium (21,37,38). The molecular elements involved in the transduction of fat (long chain fatty acid) taste are less well characterized. Our current understanding is that activation of the putative fat receptor CD36 (39) leads to phosphorylation of the MEK1/2-ERK1/2 cascade and the entry of calcium into the taste cell through CALHM1 channels (40), which are signaled either by delayed rectifying potassium (DRK) channels (41) or by Orai1 and Orai3 calcium channels controlled by STIM1 (42).

The results suggest that knockout of TIR3 had no effect on macronutrient preference whereas knockout of ITPR3 or CALHM1 biased mice toward choosing fat. T1R3 is required for the detection of sweetness and our CHO-P diet was 21% sucrose by weight, so the finding that knockout of this receptor had no effect on macronutrient selection argues against sweetness imparted by the sucrose being a major driver of CHO-P acceptance. This is surprising given the strong avidity of B6 mice (which are similar to the WT mice) for sweeteners [e.g., (43)]. However, rodents have difficulty detecting (or recognizing) sweetness in a food matrix (44). Moreover, they easily learn to associate arbitrary flavors with the postingestive benefits of sucrose even when T1R3 is absent (45,46). T1R3 is not responsible for detecting Polycose [(45); a starch-derived glucose polymer] so the T1R3 KO mice were unlikely to have had difficulty detecting cornstarch, which provided 70% of the carbohydrate contained in the CHO-P source, and is also avidly consumed by WT mice (46).

In contrast to the T1R3 KO mice, the ITPR3 KO and CALHM1 KO mice had elevated preferences for fat relative to their WT controls. Indeed, the CALHM1 KO mice ate virtually all Fat-P and no CHO-P for several days of their choice test. Both ITPR3 and CALHM1 are required for the normal detection of sweeteners and Polycose (21,38) (cornstarch has not been tested in these models) suggesting the mice may not be able to recognize the carbohydrate sources of the CHO-P diet by taste. Both molecular components are also involved in fat detection (40,42) so they also may not be able to recognize the fat source by taste. The taste of fat is generally “liked” by intact rodents (e.g., (39,40,42)) so our finding that mice with reduced or absent ability to taste it show increased preferences for it is counterintuitive but there are many ways to reconcile this, including the high concentrations of fat involved in the Fat-P diet, the potential for predominating contributions of other fat detection mechanisms, and the contribution of impurities, texture, odor and energy density. It is also possible that the diet choice is governed by carbohydrates or fats interacting with ITPR3 or CALHM1 in the gut or other post-oral sites, although to date CALHM1 expression has been observed only in taste buds and the brain (23,38).

In previous work, we demonstrated that the preference for fat was influenced by a gene or genes contained within a small region of chromosome 17 that we introgressed from the NZW to the BTBR strain (16). This region contained only 21 genes, one of which was Itpr3. Our finding here that Itpr3 knockout increases Fat-P preference shows that, indeed, Itpr3 is responsible. Itpr3 is located close to the peak of the Minc1 locus which Smith Richards and colleagues mapped in a B6 × CAST/Ei F2 intercross (12). Our earlier work raised the possibility that Itpr3 was the gene responsible for the Minc1 phenotype but the different parental strains confounded a direct comparison. The finding made here that fat preference is increased by knockout of Itpr3 in mice with a predominantly B6 background provides confirmation that Itpr3 contributes to the Minc1 phenotype.

In summary, this work makes two novel contributions. First, along with the findings of Smith Richards et al (11) we now have the ability to select mouse models that span the range from avid carbohydrate-likers to avid fat-likers. Second, we present here the first evidence of single genes—Itpr3 and Calhm1—contributing to macronutrient selection. We have begun to investigate the contribution of taste to macronutrient choice but acknowledge that so far, we have taken only some rather primitive first steps. The available genetic knockout models are crude and nonspecific tools to isolate and thus test the involvement of taste, and it may be that the mice lacking a mechanism due to gene knockout give misleading insights because they recruit mechanisms not normally used by intact animals. More generally, taste is only one of many factors likely to influence macronutrient choice. Food selection involves other sensory modalities (i.e., vision, audition, texture and odor), multiple physiological mechanisms (e.g., adaptation to fat) and appropriate neurochemistry, all modified by environment and past experience. Phenotypes under polygenic control are described as “complex traits” and macronutrient choice is undoubtedly complex.

Supplementary Material

Fig. 2.

Consumption of diets containing carbohydrate-and-protein (CHO-P) and fat-and-protein (Fat-P) during 8-day choice tests by three KO strains and their WT controls.

Research Highlights.

Mice were offered a choice between sources of carbohydrate and fat

Inbred strains differed, ranging from strong carbohydrate-likers to strong fat-likers

Mice lacking T1R3 and their controls did not differ in their carbohydrate and fat choices

Mice lacking ITPR3 or CALHM1 consumed more fat and less carbohydrate than did their controls

Acknowledgements

Supported by NIH grant RO1 DK-46791. Genotyping was performed at the Monell Genotyping and DNA Analysis Core, which is supported, in part, by funding from NIH–NIDCD Grant P30 DC-011735. AD was supported by an NIH Diversity Award supplement to NIH grant DC-10393 and the Monell Science Apprenticeship Program.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Richter CP. Total self-regulatory functions in animals and human beings. Harvey Lectures. 1942–1943;Series 38:63–103. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shor-Posner G, Grinker JA, Marinescu C, Brown O, Leibowitz SF. Hypothalamic serotonin in the control of meal patterns and macronutrient selection. Brain Res Bull. 1986;17:663–671. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(86)90198-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welch CC, Grace MK, Billington CJ, Levine AS. Preference and diet type affect macronutrient selection after morphine, NPY, norepinephrine, and deprivation. Am J Physiol Regul Integ Comp Physiol. 1994;266:R426–R433. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.2.R426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deems RO, Friedman MI. Macronutrient selection in an animal model of cholestatic liver disease. Appetite. 1988;11:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(88)80007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartness TJ, Waldbillig RJ. Dietary self-selection in intact, ovariectomized, and estradiol-treated female rats. Behav Neurosci. 1984;98:125–137. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.98.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sclafani A, Aravich PF. Macronutrient self-selection in three forms of hypothalamic obesity. Am J Physiol Regul Integ Comp Physiol. 1983;244:R686–R694. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1983.244.5.R686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thibault L, Booth DA. Macronutrient-specific dietary selection in rodents and its neural bases. Neurosci Biobeh Rev. 1999;23:457–528. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(98)00047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reed DR, Friedman MI, Tordoff MG. Experience with a macronutrient source influences subsequent macronutrient selection. Appetite. 1992;18:223–232. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(92)90199-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanarek RB. Determinants of dietary self-selection in experimental animals. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985;42:940–950. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/42.5.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galef BG., Jr A contrarian view of the wisdom of the body as it relates to dietary self-selection. Psychol Rev. 1991;98:218–223. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.98.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith Richards BK, Andrews PK, West DB. Macronutrient diet selection in thirteen mouse strains. Am J Physiol Regul Integ Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R797–R805. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.4.R797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith Richards BK, Belton BN, Poole AC, Mancuso JJ, Churchill GA, Li R, et al. QTL analysis of self-selected macronutrient diet intake: fat, carbohydrate, and total kilocalories. Physiol Genomics. 2002;11:205–217. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00037.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar KG, Poole AC, York B, Volaufova J, Zuberi A, Richards BK. Quantitative trait loci for carbohydrate and total energy intake on mouse chromosome 17: congenic strain confirmation and candidate gene analyses (Glo1, Glp1r) Am J Physiol Regul Integ Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R207–R216. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00491.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar KG, Smith Richards BK. Transcriptional profiling of chromosome 17 quantitative trait loci for carbohydrate and total calorie intake in a mouse congenic strain reveals candidate genes and pathways. J Nutrigenet Nutrigenomics. 2008;1:155–171. doi: 10.1159/000113657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar KG, DiCarlo LM, Volaufova J, Zuberi AR, Richards BK. Increased physical activity cosegregates with higher intake of carbohydrate and total calories in a subcongenic mouse strain. Mammal Genome. 2010;21:52–63. doi: 10.1007/s00335-009-9243-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tordoff MG, Jaji SA, Marks JM, Ellis HT. Macronutrient choice of BTBR.NZW mice congenic for a 21-gene region of chromosome 17. Physiol Behav. 2012;106:556–561. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petkov PM, Ding Y, Cassell MA, Zhang W, Wagner G, Sargent EE, et al. An efficient SNP system for mouse genome scanning and elucidating strain relationships. Genome Res. 2004;14:1806–1811. doi: 10.1101/gr.2825804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Witmer PD, Doheny KF, Adams MK, Boehm CD, Dizon JS, Goldstein JL, et al. The development of a highly informative mouse simple sequence length polymorphism (SSLP) marker set and construction of a mouse family tree using parsimony analysis. Genome Res. 2003;13:485–491. doi: 10.1101/gr.717903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tordoff MG, Bachmanov AA, Reed DR. Forty mouse strain survey of voluntary calcium intake, blood calcium, and bone mineral content. Physiol Behav. 2007;91:632–643. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Jackson Laboratory. Mouse phenome database web site. 2001 http://www.jax.org/phenome. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tordoff MG, Ellis HT. Taste dysfunction in BTBR mice due to a mutation of Itpr3, the inositol triphosphate receptor 3 gene. Physiol Genomics. 2013;45:834–855. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00092.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dreses-Werringloer U, Lambert JC, Vingtdeux V, Zhao H, Vais H, Siebert A, et al. A polymorphism in CALHM1 influences Ca2+ homeostasis, Aβ levels, and Alzheimer's disease risk. Cell. 2008;133:1149–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma Z, Siebert AP, Cheung KH, Lee RJ, Johnson B, Cohen AS, et al. Calcium homeostasis modulator 1 (CALHM1) is the pore-forming subunit of an ion channel that mediates extracellular Ca2+ regulation of neuronal excitability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E1963–E1971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204023109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reed DR, Bachmanov AA, Tordoff MG. Forty mouse strain survey of body composition. Physiol Behav. 2007;91:593–600. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flowers JB, Oler AT, Nadler ST, Choi Y, Schueler KL, Yandell BS, et al. Abdominal obesity in BTBR male mice is associated with peripheral but not hepatic insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E936–E945. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00370.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tordoff MG, Tepper BJ, Friedman MI. Food flavor preferences produced by drinking glucose and oil in normal and diabetic rats: evidence for conditioning based on fuel oxidation. Physiol Behav. 1987;41:481–487. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(87)90084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellush LL, Rowland NE. Dietary self-selection in diabetic rats: an overview. Brain Res Bull. 1986;17:653–661. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(86)90197-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reed DR, Friedman MI, Tordoff MG. Experience with a macronutrient source influences subsequent macronutrient selection. Appetite. 1992;18:223–232. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(92)90199-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crabbe JC, Wahlsten D, Dudek BC. Genetics of mouse behavior: interactions with laboratory environment. Science. 1999;284:1670–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5420.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bachmanov AA, Li X, Reed DR, Ohmen JD, Li S, Chen Z, et al. Positional cloning of the mouse saccharin preference (Sac) locus. Chem Senses. 2001;26:925–933. doi: 10.1093/chemse/26.7.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blednov YA, Walker D, Martinez M, Levine M, Damak S, Margolskee RF. Perception of sweet taste is important for voluntary alcohol consumption in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaudhari N, Pereira E, Roper SD. Taste receptors for umami: the case for multiple receptors. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:738S–742S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27462H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Max M, Shanker YG, Huang L, Rong M, Liu Z, Campagne F, et al. Tas1r3, encoding a new candidate taste receptor, is allelic to the sweet responsiveness locus Sac. Nature Genetics. 2001;28:58–63. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reed DR, Li S, Li X, Huang L, Tordoff MG, Starling-Roney R, et al. Polymorphisms in the taste receptor gene (Tas1r3) region are associated with saccharin preference in 30 mouse strains. J Neurosci. 2004;24:938–946. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1374-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tordoff MG, Alarcon LK, Valmeki S, Jiang P. T1R3: A human calcium taste receptor. Sci Rep. 2012;2:496. doi: 10.1038/srep00496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tordoff MG, Shao H, Alarcon LK, Margolskee RF, Mosinger B, Bachmanov AA, et al. Involvement of T1R3 in calcium-magnesium taste. Physiol Genomics. 2008;34:338–348. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.90200.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hisatsune C, Yasumatsu K, Takahashi-Iwanaga H, Ogawa N, Kuroda Y, Yoshida R, et al. Abnormal taste perception in mice lacking the type 3 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37225–37231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taruno A, Vingtdeux V, Ohmoto M, Ma Z, Dvoryanchikov G, Li A, et al. CALHM1 ion channel mediates purinergic neurotransmission of sweet, bitter and umami tastes. Nature. 2013;495:223–226. doi: 10.1038/nature11906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laugerette F, Passilly-Degrace P, Patris B, Niot I, Febbraio M, Montmayeur JP, et al. CD36 involvement in orosensory detection of dietary lipids, spontaneous fat preference, and digestive secretions. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3177–3184. doi: 10.1172/JCI25299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subramaniam S, Ozdener MH, Abdul-Azize S, Saito K, Malik B, Marambaud P, et al. ERK1/2 and CALHM1 channels in taste bud cells regulate preference for fat. Nature Neurosci. (under review). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gilbertson TA, Fontenot DT, Liu L, Zhang H, Monroe WT. Fatty acid modulation of K+ channels in taste receptor cells: gustatory cues for dietary fat. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:C1203–C1210. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.4.C1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dramane G, Abdoul-Azize S, Hichami A, Vogtle T, Akpona S, Chouabe C, et al. STIM1 regulates calcium signaling in taste bud cells and preference for fat in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2267–2282. doi: 10.1172/JCI59953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bachmanov AA, Beauchamp GK. Amino acid and carbohydrate preferences in C57BL/6ByJ and 129P3/J mice. Physiol Behav. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mook DG. Saccharin preference in the rat: Some unpalatable findings. Psychological Reviews. 1974;81:475–490. doi: 10.1037/h0037238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zukerman S, Glendinning JI, Margolskee RF, Sclafani A. T1R3 taste receptor is critical for sucrose but not Polycose taste. Am J Physiol Regul Integ Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R866–R876. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90870.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zukerman S, Glendinning JI, Margolskee RF, Sclafani A. Impact of T1r3 and Trpm5 on carbohydrate preference and acceptance in C57BL/6 mice. Chem Senses. 2013;38:421–437. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjt011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.