Abstract

Objective

A reduced response of articular chondrocytes to growth factors with aging could contribute to the development of osteoarthritis. The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of aging and oxidative stress on the response of human articular chondrocytes to insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and osteogenic protein-1 (OP-1).

Methods

Chondrocytes isolated from normal human articular cartilage obtained from tissue donors were cultured in alginate beads or monolayer. Cells were stimulated with 50–100 ng/ml of IGF-1, OP-1, or both. Oxidative stress was induced using tert-butyl-hydroperoxide. Sulfate incorporation was used to measure proteoglycan synthesis and cell lysates to evaluate signaling proteins by immunoblotting. Confocal microscopy was used to measure nuclear translocation of Smad4.

Results

Chondrocytes isolated from tissue donors ranging in age from 24 to 81 years demonstrated an age-related decline in IGF-1 and IGF-1+OP-1 stimulated proteoglycan synthesis. Induction of oxidative stress inhibited both IGF-1 and OP-1 stimulated proteoglycan synthesis. Signaling studies revealed oxidative stress inhibited IGF-1 stimulated Akt phosphorylation while increasing phosphorylation of ERK and these effects were greater in cells from older donors. Oxidative stress also increased p38 phosphorylation which resulted in phosphorylation of Smad1 at the Ser206 inhibitory site and reduced Smad1 nuclear accumulation. Oxidative stress also modestly reduced OP-1 stimulated nuclear translocation of Smad4.

Conclusion

These results demonstrate an age-related reduction in response of human chondrocytes to IGF-1 and OP-1, two important anabolic factors in cartilage, and suggest oxidative stress may be a contributing factor by altering IGF-1 and OP-1 signaling.

The development of osteoarthritis (OA) has been linked closely to aging but the mechanisms responsible are incompletely understood. The loss of articular cartilage seen during the development of OA is related to an imbalance in anabolic and catabolic activity by the resident chondrocytes (1–3). Because growth factors such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and osteogenic protein-1 (OP-1) are pro-anabolic and anti-catabolic (4, 5), reduced responsiveness to growth factor stimulation could play a key role in the link between aging and OA.

There is evidence for an age-related decline in chondrocyte response to IGF-1 in bovine (6), rat (7, 8), and monkey chondrocytes (9). However, there is a lack of data for human chondrocytes, most likely due to the difficulty in obtaining sufficient numbers of samples from normal cartilage of young and old humans. One previous study demonstrated an age-related decrease of human chondrocytes in the mitogenic response to IGF-1 but the anabolic response was not measured (10). However, IGF-1 is the major growth factor responsible for the stimulation of proteoglycan synthesis by serum and the ability of 10% serum to stimulate sulfate incorporation by human chondrocytes in explant culture was shown to decrease with donor age (11).

Growth factors do not act alone in tissues such as articular cartilage that contain multiple growth factors acting in concert to regulate cell function. In addition to IGF-1, OP-1 (also known as bone morphogenetic protein-7) is an important anabolic factor in adult articular cartilage (12, 13). Previous studies have demonstrated that chondrocytes isolated from either normal or osteoarthritic cartilage have better survival and produce more matrix when stimulated with the combination of IGF-1 and OP-1 as compared to cells treated with either growth factor alone (4, 14). Likewise, the combination of IGF-1 and OP-1 was more effective than either growth factor alone at inhibiting chondrocyte MMP production in response to IL-1β or fibronectin fragments (5). However, chondrocyte expression of OP-1 declined with increasing age and this was accompanied by a decrease in the endogenous levels of OP-1 in cartilage (15).

We have previously shown that IGF-1 stimulated phosphorylation of the cell signaling protein Akt is necessary for proteoglycan synthesis in normal chondrocytes and this was reduced in OA chondrocytes and in normal chondrocytes under conditions of oxidative stress (16, 17). It is not known how aging might alter the articular chondrocyte cell signaling response to IGF-1 or OP-1 that mediates matrix synthesis. The purpose of the present study was to determine if aging affects the response of normal adult human articular chondrocytes stimulated with IGF-1 and OP-1 alone and in combination and to determine if altered cell signaling due to oxidative stress played a role. The results support an age-related decline in human chondrocyte growth factor response that may be due to altered cell signaling mediated by oxidative stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chondrocyte isolation and culture

Normal human cartilage was obtained from the ankle joints of tissue donors through the Gift of Hope Organ and Tissue Donor Network (Elmhurst, IL) or the National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI, Philadelphia, PA). Joints from 33 individual donors were acquired. The donors had no known history of joint disease and each joint was graded on a modified Collin’s scale for gross evidence of damage as described (18). Collin’s grade 0 or 1 was considered to be normal cartilage.

Chondrocytes were isolated enzymatically from cartilage slices removed from the joints as previously described (14). After isolation, viability and cell count were determined using trypan blue exclusion and then the cells were cultured either in alginate beads or in monolayers. Alginate beads were used for the experiments shown in Figure 1 and all other experiments were done in high density monolayers. For alginate bead experiments, the cells were resuspended at 2×106 cells/ml in sodium alginate and alginate beads were produced as previously described resulting in approximately 20,000 cells per bead (9). The beads were cultured at 8 beads per well in 24 well plates in 0.5 ml/well of serum-free DMEM:Ham’s F-12 (1:1). All media was supplemented with 1% mini-ITS+ which contains 5 nM insulin (“mini”-dose insulin so that the IGF-1 receptor is not stimulated), 2 μg/ml transferrin, 2 ng/ml selenous acid, 25 μg/ml ascorbic acid, and BSA/linoleic acid at 420/2.1 μg/ml (9). For high-density monolayer culture experiments, isolated cells were plated in 6-well plates at 2 × 106 cells/well in DMEM: Ham’s F-12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. Confluent primary cultures were changed to serum-free media and used the next day for stimulation experiments.

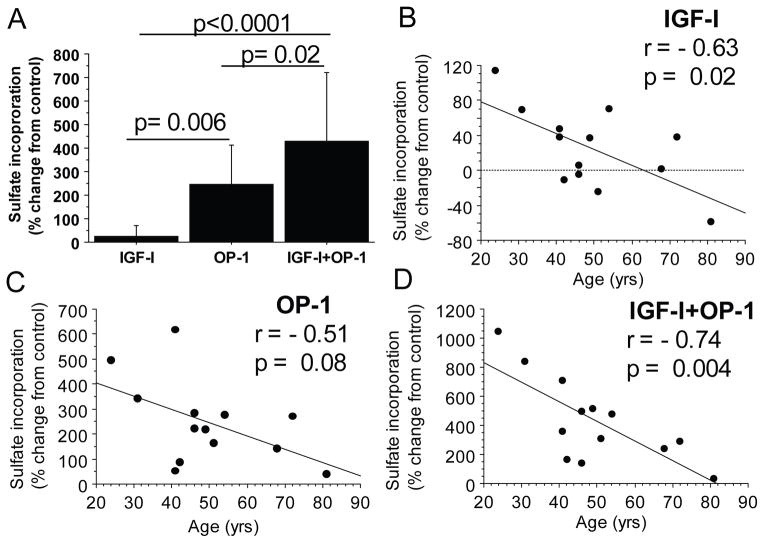

Figure 1.

Effect of age on proteoglycan synthesis stimulated by IGF-1 and OP-1. Human articular chondrocytes from 13 tissue donors ages 24 to 81 years old were cultured in alginate beads and treated with control media or 100ng/ml of IGF-1, OP-1 or both. Proteoglycan synthesis was measured by sulfate incorporation normalized to cell numbers by DNA content. A) Comparison of sulfate incorporation relative to unstimulated controls for all donors. Results shown are mean± standard deviation. B, C and D) Relationship between donor age and sulfate incorporation stimulated by IGF-1 (B), OP-1 (C), and IGF-1+OP-1 (D).

Proteoglycan synthesis

In order to examine the effect of donor age on the response to IGF-1 and OP-1, proteoglycan synthesis assays were performed in cells cultured in alginate beads as detailed above. IGF-1 treated wells received 100 ng/ml of recombinant human IGF-1 (gift from Chiron Corporation, Emeryville, CA or purchased from Austral Biologicals (San Ramon, CA), OP-1 treated wells received 100 ng/ml recombinant human OP-1 (provided by Stryker Biotech, Hopkinton, MA) and the combination treatment wells received 100 ng/ml of each growth factor. Triplicate wells were used for each condition. Medium was changed every 48 hours with the addition of fresh growth factor to the treated wells. Proteoglycan synthesis was measured at day 7 using the sulfate incorporation assay, corrected for cell numbers by a DNA assay, as previously described (14).

The experiments examining the effect of oxidative stress on proteoglycan synthesis were performed using confluent monolayer cultures. Cells were changed to serum-free media for 6 hours and then pre-treated for 30 minutes with 25μM tert-butylhydroperoxide (tBHP, Sigma) followed by addition of 100 ng/ml IGF-1 or OP-1. After an overnight incubation, proteoglycan synthesis was measured using the sulfate incorporation assay as described (17).

Analysis of intracellular signaling by immunoblotting

Cell signaling studies were performed as previously described in detail (17). Briefly, overnight serum-free confluent monolayer cultures were treated with 50 ng/ml IGF-1 or OP-1 or the combination of the two. For oxidative stress experiments, cells were pre-treated for 30 minutes with 250μM tBHP prior to addition of growth factors. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase inhibitor studies utilized 10μM of the MEK inhibitor U0126 to block ERK, 10μM SB203580 to block p38, and 20μM SP600125 to block JNK and were added 30 minutes prior to tBHP. Cultures were lysed at the indicated time points after addition of growth factors and lysates used for analysis of cell signaling proteins by immunoblotting with phospho-specific antibodies and with antibodies to total protein (non-phospho-specific) as a control for protein loading. Phospho-Akt (Ser473), Akt, phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), ERK1/2, phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182), p38, phospho-Smad1(Ser463/465)/Smad5(Ser463/465)/Smad8(Ser426/428), phospho-Smad1(Ser206) and Smad1 antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology. The phospho-JNK (Tyr183/185) and JNK2 antibodies were from Invitrogen. The cytosolic and nuclear samples were prepared from cell lysates using the NE-PER kit from Pierce. Densitometry was performed using Eastman Kodak 1D 3.6 image analysis software.

Smad4 nuclear translocation

Analysis of Smad4 activation was performed by measuring the translocation of Smad4 from the cytoplasm into the nucleus by confocal microscopy. We used a previously published protocol (19) except the secondary antibody was an anti-rabbit antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor® 488 (Invitrogen) and nuclear staining was performed with TO-PRO®-3 Iodide (Invitrogen). Approximately 100 cells on each slide were counted and cells in the green (Smad4) and red (nuclear stain) overlay images that had a bright yellow fluorescence were counted as positive for nuclear translocation of Smad4.

Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was performed at least three times with cells from independent tissue donors. The number of independent samples used for each experiment is provided in the text or figure legends. Unless indicated, results are shown as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using Statview software (SAS Institute). Simple linear regression was used to analyze the relationship between age and sulfate incorporation. The other results were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA).

RESULTS

Age-related reduction in growth factor stimulated chondrocyte proteoglycan synthesis

Human articular chondrocytes isolated from normal donor tissue from 13 individuals were stimulated while in alginate bead cultures. The ages of the donors ranged from 24 to 81 yrs old (mean 49.7±16). Independent of age, proteoglycan synthesis was greatest in cultures treated with the combination of IGF-1 and OP-1 (average of 429% change from control) followed by OP-1 (247%) alone and IGF-1 alone (24%) (Figure 1A). With increasing age, there was a significant decline in the response to IGF-1 (r=−0.63, p=0.02, Figure 1B) and to IGF-1 + OP-1 (r=−0.74, p=0.004, Figure 1D) with a trend towards a decline in response to OP-1 alone (r=−0.51, p=0.08, Figure 1C).

Effects of oxidative stress on the response of chondrocytes to growth factor stimulation

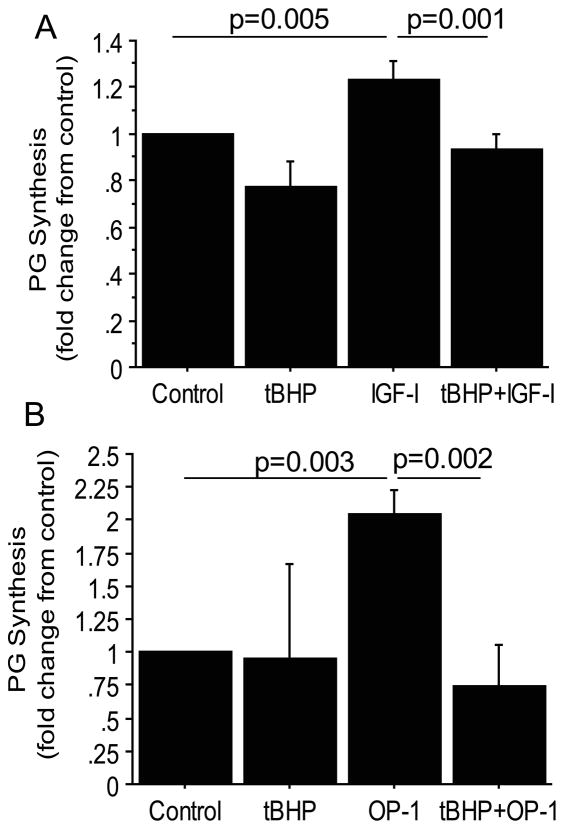

We previously noted that oxidative stress increased with increasing age in normal human articular chondrocytes (20) and that induction of oxidative stress in vitro impaired IGF-1 stimulated signaling in chondrocytes (17). In order to determine if oxidative stress could reduce proteoglycan synthesis in response to growth factors, chondrocytes were treated with tBHP, a glutathione peroxidase substrate that induces oxidative stress by decreasing the cell’s content of reduced glutathione and increasing the amount of oxidized glutathione (21). Treatment with tBHP reduced both IGF-1 (Figure 2A) and OP-1 (Figure 2B) stimulated proteoglycan synthesis. We did not have sufficient cells for these experiments to include tBHP with the combination of IGF-1+OP-1but would expect a similar reduction in response based on the signaling studies below.

Figure 2.

Oxidative stress inhibition of proteoglycan synthesis stimulated by IGF-1 or OP-1. Human articular chondrocytes in confluent monolayers were pre-treated for 30 minutes with 25μM tert-butylhydroperoxide (tBHP) to induce oxidative stress or control media followed by 100ng/ml IGF-1 or OP-1 treatment overnight. Proteoglycan (PG) synthesis was measured by the sulfate incorporation assay normalized to cell numbers by DNA content in response to IGF-1 (A) and OP-1 (B). Results shown are the mean± standard deviation. N=3 independent donors for IGF-1 and n=4 independent donors for OP-1.

Oxidative stress disrupts chondrocyte IGF-1 signaling

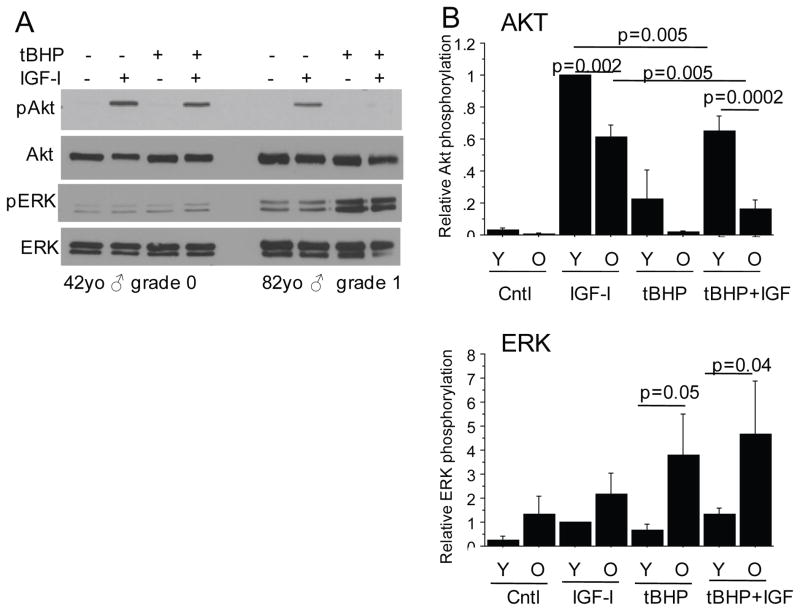

We examined the effects of treatment with tBHP on the cell signaling response to the growth factors in order to determine the mechanism for proteoglycan synthesis inhibition. We had previously shown that proteoglycan synthesis stimulated by IGF-1 required activation of Akt while ERK activation was inhibitory (16, 17). In preliminary experiments, we did not detect any stimulation of Akt or ERK in cells treated with OP-1 and so focused the first set of experiments on IGF-1. As we had previously reported (17), tBHP pre-treatment inhibited IGF-1 stimulated Akt phosphorylation. Here we extended those findings to determine the effects of age. For these experiments, we chose age 50 years old to separate younger and older adults because osteoarthritis becomes more common after the age of 50 (22) and the response to growth factors shown in Figure 1 dropped around age 50.

Relative to older adults, chondrocytes from younger adults had a higher level of Akt phosphorylation in response to IGF-1 and were much less affected by tBHP (Figure 3 A and B). In contrast, ERK phosphorylation in response to tBHP treatment was greater in cells from older adults compared to younger adults, both in cells treated with tBHP alone and in those treated with tBHP prior to IGF-1 (Figure 3A and B). These results are consistent with increased susceptibility to oxidative stress with age resulting in an imbalance in Akt and ERK activity.

Figure 3.

Effects of oxidative stress on phosphorylation of Akt and ERK in normal chondrocytes from young and old donors. For these experiments young (Y) was <50 years-old and old (O) was >50 years-old. Human articular chondrocytes in confluent serum-free monolayer cultures were pre-treated for 30 minutes with 250μM tert-butylhydroperoxide (tBHP) to induce oxidative stress or control media followed by stimulation with IGF-1 or control media. After 30 minutes, cell lysates were prepared and immunoblotted with antibodies to phosphorylated Akt (pAkt) or phosphorylated ERK (pERK). The blots were then stripped and reprobed with the respective antibodies to total Akt and ERK. A) Representative immunoblots from a young and old donor. (B) Results of densitometric analysis from immunoblots of n=4 independent donors in each age group. Relative phosphorylation is the phosphorylated protein band density relative to the density of the total band for each sample. Results shown are the mean ± standard deviation.

Effects of oxidative stress on chondrocyte OP-1 signaling

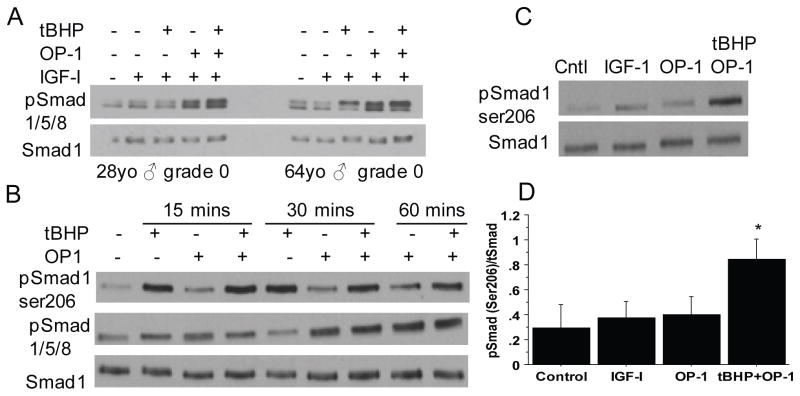

Next, we examined the effect of oxidative stress on phosphorylation of Smads 1/5/8 which are upstream in the canonical signaling pathway stimulated by OP-1(19). We first tested an antibody that recognizes a phosphorylation site in all three of the Smads and therefore cannot distinguish Smad1 from Smad5 or Smad8 which run at the same location of gels while the antibody to total Smad used as a control is specific for Smad1. The phosphorylation site is in the conserved SSXS motif in the C-terminal region of the all three Smads and is associated with BMP signals that increase Smad activity (23). As expected, we detected phosphorylation at this site in chondrocytes treated with OP-1 but not in cultures treated with IGF-1 or tBHP (Figure 4A and B). The response to IGF-1+OP-1 was similar to OP-1 alone, indicating IGF-1 did not promote OP-1 signaling via Smads1/5/8 phosphorylation. Treatment with tBHP did not alter OP-1 or IGF-1+OP-1 induced Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation at the activating site (Figure 4A and B).

Figure 4. Effect of age and oxidative stress on phosphorylation of Smads 1/5/8.

(A) Chondrocytes cultured in monolayers from donors aged 28 and 64 years were treated with tBHP to induce oxidative stress followed by 30 minutes of stimulation with IGF-1 or IGF-1 plus OP-1. Cell lysates were prepared and immunoblotted with an antibody to the activating phosphorylation site present in all 3 Smads (pSmad1/5/8). Blots were stripped and re-probed with an antibody to total Smad 1. (B) Chondrocytes from a 67 year-old donor were pre-treated with tBHP or control media for 30 minutes followed by time course stimulation by OP-1. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with an antibody to the Smad1 inhibitory Ser206 phosphorylation site (pSmad1ser206) or the active site Smad1/5/8 and total Smad1 antibodies as in panel A. (C) Chondrocytes were treated with IGF-1 or OP-1 for 30 minutes or tBHP for 30 minutes followed by OP-1 and lystates were immunoblotted as in panel B. (D) Densitometry results from immunoblots as shown in (C) from n=4 independent donors. Results are mean± standard deviation. *p=0.002 for tBHP+OP-1 vs. OP-1, p=0.004 for tBHP+OP-1vs control and p=0.001 for tBHP+OP-1vs IGF-1

There are additional phosphorylation sites in Smad1 in what has been termed the linker region due to its location between the MH1 and MH2 globular domains. Phosphorylation at these sites, which is mediated by MAP kinases, has been shown to inhibit the nuclear accumulation and the transcriptional activity of Smad1 (24). Immunoblotting of chondrocyte lysates from a time course experiment with an antibody that recognizes Ser206 phosphorylation of Smad1 in the linker region revealed increased phosphorylation in chondrocytes treated with tBHP as early as 15 minutes after stimulation and in cultures treated with tBHP prior to OP-1 (Figure 4B). The same lysates were immunoblotted for the Smad1/5/8 active site phosphorylation which was strongest with OP-1 alone at 30 minutes and not significantly altered by pre-treatment with tBHP (Figure 4B).

Additional experiments were performed at the 30 minute time point which revealed a consistent increase in Smad1 ser206 phosphorylation in cells treated with tBHP prior to OP-1 when compared to IGF-1 or OP-1 alone (Figure 4C and D). These results demonstrate that tBHP-induced oxidative stress increases the level of phosphorylation of Smad1 at an inhibitory site in the linker region without altering phosphorylation at the active site.

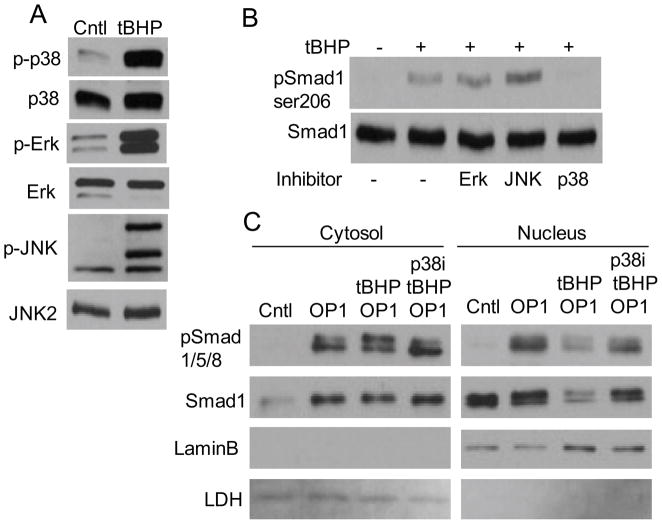

We next examined which of the MAP kinases was responsible for Smad1 linker region phosphorylation. Treatment of chondrocytes with tBHP resulted in a similar increase in phosphorylation of p38, ERK and JNK (Figure 5A). When chondrocytes were pre-treated with MAP kinase inhibitors, only the p38 inhibitor blocked tBHP induced Smad1 linker region phosphorylation (Figure 5B). As noted above, Smad1 linker region phosphorylation reduces nuclear accumulation of Smad1 which we found also occurred in cells treated with tBHP prior to OP-1 (Figure 5C). Pre-treatment with the p38 inhibitor blocked this effect of tBHP.

Figure 5.

MAP kinase activation by oxidative stress and effects on phosphorylation of Smad1 in the linker region. (A) Chondrocyte lysates from cells treated for 30 minutes with control media or media with 250μM tBHP were immunoblotted with antibodies to phosphorylated (p-) p38, Erk, or JNK. The blots were then stripped and reprobed with antibodies to the total protein as control. Note, the p-JNK antibody recognizes JNK2 (upper band) and JNK1 (middle band) as well as a background band while the total JNK antibody recognizes JNK2. (B) Chondrocytes were pre-treated for 30 minutes with control media or MAP kinase inhibitors (described in the Methods) and the treated with tBHP for 30 minutes. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for pSmad1ser206 or total Smad 1 as in Figure 4. (C) Chondrocytes were pre-treated with tBHP and the p38 inhibitor as in panel B and then stimulated with OP-1 for 30 minutes. Cell lysates were used to prepare cytosol and nuclear fractions which were used for immunoblotting with Smad antibodies as indicated or with antibodies to LaminB (a nuclear protein) and LDH (a cytosolic protein).

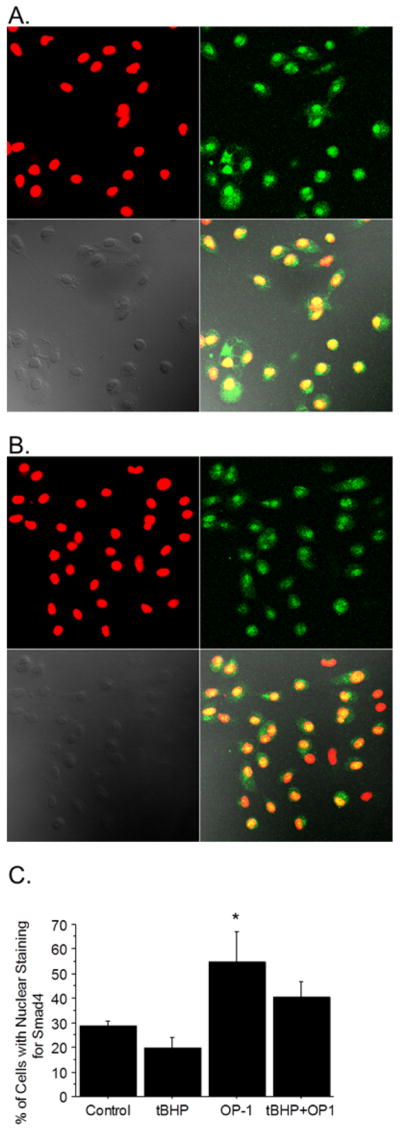

The activation and translocation of Smad4 into the nucleus is another important step downstream in the OP-1 signaling pathway and so we determined if oxidative stress induced by tBHP altered this step. For these experiments, we used an anti-Smad4 antibody and measured nuclear translocation by confocal microscopy. Treatment of chondrocytes with OP-1 for 30 minutes resulted in a significant increase in nuclear Smad4 that was partially inhibited by tBHP (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of oxidative stress on Smad 4 nuclear translocation. Chondrocytes were cultured on coverslips and pre-treated with tBHP or control media for 30 minutes followed by 30 minutes of OP-1. The cells were then fixed and permeabilized and slides were incubated with rabbit anti-Smad4 antibodies followed by Alexa-fluor anti-rabbit antibody (green fluorescence). The nuclei were stained with TO-PRO3 (red). A) Representative images from cells treated with OP-1 alone and B) from tBHP + OP-1 treated cells. Panels going clockwise show the red nuclear fluorescence, green Smad4 fluorescence, the overlay of red and green, and a phase contrast image. (C) Approximately 100 cells per slide with or without nuclear staining for Smad4 (yellow) were counted and expressed as a % of total cells counted. Results are mean ± standard deviation from an n of 3 independent donors. *p=0.04 vs. control.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study using primary cultures of human articular chondrocytes to demonstrate an age-related reduction in the ability of IGF-1 and IGF-1 plus OP-1 to stimulate proteoglycan synthesis. These two growth factors are important in the maintenance of cartilage homeostasis and a loss in chondrocyte responsiveness could contribute to the development of age-related OA. Consistent with a previous study where matrix production was measured after 21 days in alginate culture (14), we found that the combination of IGF-1 and OP-1 was more potent than either growth factor alone in stimulating proteoglycan synthesis, independent of donor age. Our present results, using normal chondrocytes from young and old tissue donors, combined with previous work using chondrocytes from normal and OA joints (17) suggest that the reduced anabolic response to IGF-1 and to OP-1 can be due to disrupted cell signaling caused by oxidative stress.

Oxidative stress, resulting from elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) relative to levels of anti-oxidants, is thought to be a major contributor to many of the chronic disease associated with aging (25) including OA (26, 27). Using human cartilage from tissue donors, we have previously shown an age-related decrease in the amount of reduced relative to oxidized glutathione which is consistent with age-related oxidative stress (20). There is evidence for other changes in the anti-oxidant capacity of chondrocytes with aging including a decrease in catalase noted in rat cartilage (28) and a decrease in the mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2) noted in human chondrocytes (29). Similar to our findings of increased oxidative stress induced by tBHP in human chondrocytes from older adults, Jallali et al (28) demonstrated that ROS levels induced by menadione were higher in chondrocytes from older rats.

In addition to causing damage to proteins, lipids, and DNA, elevated levels of ROS can alter the activity of specific cell signaling pathways that are critical to maintaining normal cell function (25). Intracellular signaling pathways activated by IGF-1 via the IGF-1 receptor include the IRS-1-PI-3-kinase-Akt pathway and the Shc-Grb2-SOS-Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathway. We have previously shown that the ability of IGF-1 to stimulate chondrocyte matrix production, including proteoglycans and type II collagen, requires activation of Akt while ERK is inhibitory (16, 17). Induction of oxidative stress with tBHP was found to alter the balance of Akt to ERK phosphorylation to favor ERK which results in the inhibition of proteoglycan and collagen production. Here we show that when compared to chondrocytes from younger donors, chondrocytes from older donors exhibited lower levels of Akt phosphorylation in response to IGF-1 that correlates with the reduced proteoglycan synthesis. In addition, cells from older donors treated with tBHP exhibited greater inhibition of IGF-1 stimulated Akt phosphorylation accompanied by increased ERK phosphorylation consistent with the older chondrocytes being more sensitive to oxidative stress induction.

Although we found a significant decline with age in proteoglycan synthesis in chondrocytes treated with IGF-1 and IGF-1 + OP-1, we only noted a trend (p=0.08) towards a reduced response with OP-1 alone. Chondrocyte proteoglycan synthesis has been reported to decline with age in response to the related BMP family members BMP-6 (30) and TGFβ (31) but OP-1 had not been previously studied. We did observe that induction of oxidative stress using tBHP inhibited OP-1 stimulated proteoglycan synthesis.

Unlike IGF-1, little is known about ROS regulation of BMP signaling. There is some evidence that ROS generated by NAD(P)H oxidases can promote BMP-2 stimulated gene transcription in bone and vascular tissue (32, 33) but effects on specific BMP pathway signaling proteins have not been investigated and we are not aware of previous studies that have examined an effect of ROS on OP-1 signaling. We could not detect a significant effect of oxidative stress on Smad 1,5,8 phosphorylation at the BMP-activating site but, interestingly, did detect increased phosphorylation in the Smad1 linker region at Ser 206 which has been found to inhibit Smad1 accumulation and activity in the nucleus (24). Phosphorylation at this site has been shown to be mediated by members of the MAP kinase family including ERK (24) which we found was activated in chondrocytes by oxidative stress (Figure 3) and is a major contributor to inhibition of IGF-1 stimulated proteoglycan synthesis (17). However, although tBHP induced phosphorylation of ERK as well as p38 and JNK, inhibitor experiments revealed that p38 mediated Smad1 linker region phosphorylation and this was associated with reduced nuclear accumulation of Smad1 in response to OP-1. In previous work, IL-1β was shown to inhibit chondrocyte OP-1 signaling via linker region phosphorylation mediated by the JNK and p38 MAP kinases (19). These results indicate that MAP kinase activation resulting in Smad1 inhibition through phosphorylation in the linker region is an important mechanism for inhibition of chondrocyte OP-1 activity by oxidative stress and cytokines.

In addition, we measured a modest (14%) decrease in Smad 4 translocation into the nucleus in chondrocytes treated with tBHP suggesting a second mechanism for oxidative stress inhibition of OP-1 may be involved. This level of inhibition by itself may not be sufficient to explain the almost complete inhibition of OP-1 stimulated proteoglycan synthesis by tBHP but may be when combined with inhibition of Smad1 activity. The Smads function as a complex to regulate gene transcription although Smad1 can regulate some transcriptional activity on its own (24).

In summary, using human articular chondrocytes isolated from normal joints of young and older adult tissue donors, we found an age-related reduction in the ability of IGF-1 and IGF-1 plus OP-1 to stimulate proteoglycan synthesis with a trend towards a reduced response to OP-1 alone. Chondrocytes from older donors were more susceptible to the effects of oxidative stress on IGF-1 signaling resulting in an imbalance in Akt and ERK phosphorylation. Oxidative stress was also found to inhibit OP-1 activity, likely through p38 mediated phosphorylation of Smad1 in the inhibitory linker region resulting in reduced nuclear accumulation of Smad1 combined with reduced Smad4 nuclear translocation. These findings support the hypothesis that oxidative stress resulting in a reduced growth factor response may be an important contributing factor to the development of age-related osteoarthritis.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grant AG-044034 (RL), The Dorothy Rhyne Kimbrell and Willard Duke Kimbrell Professorship (RL) and the Ciba Geigy Endowed Chair (SC).

We would like to thank NDRI and the Gift of Hope Tissue and Organ Donor Network and the donor families for providing human donor tissues. We also thank Dr. David Rueger from Stryker Biotech for providing OP-1.

Contributor Information

Richard F. Loeser, Department of Internal Medicine, Section on Molecular Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Uma Gandhi, Department of Internal Medicine, Section on Molecular Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

David L. Long, Department of Internal Medicine, Section on Molecular Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina

Weihong Yin, Department of Internal Medicine, Section on Molecular Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Susan Chubinskaya, Department of Biochemistry, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois.

References

- 1.Pelletier JP, Martel-Pelletier J, Abramson SB. Osteoarthritis, an inflammatory disease: potential implication for the selection of new therapeutic targets. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1237–47. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200106)44:6<1237::AID-ART214>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldring MB, Marcu KB. Cartilage homeostasis in health and rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:224. doi: 10.1186/ar2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loeser RF, Goldring SR, Scanzello CR, Goldring MB. Osteoarthritis: A disease of the joint as an organ. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1697–707. doi: 10.1002/art.34453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chubinskaya S, Hakimiyan A, Pacione C, Yanke A, Rappoport L, Aigner T, et al. Synergistic effect of IGF-1 and OP-1 on matrix formation by normal and OA chondrocytes cultured in alginate beads. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:421–30. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Im HJ, Pacione C, Chubinskaya S, Van Wijnen AJ, Sun Y, Loeser RF. Inhibitory effects of insulin-like growth factor-1 and osteogenic protein-1 on fibronectin fragment- and interleukin-1beta-stimulated matrix metalloproteinase-13 expression in human chondrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25386–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302048200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barone-Varelas J, Schnitzer TJ, Meng Q, Otten L, Thonar EJ. Age-related differences in the metabolism of proteoglycans in bovine articular cartilage explants maintained in the presence of insulin-like growth factor I. Connect Tissue Res. 1991;26:101–20. doi: 10.3109/03008209109152167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin JA, Ellerbroek SM, Buckwalter JA. Age-related decline in chondrocyte response to insulin-like growth factor-I: the role of growth factor binding proteins. J Orthop Res. 1997;15:491–8. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100150403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Messai H, Duchossoy Y, Khatib A, Panasyuk A, Mitrovic DR. Articular chondrocytes from aging rats respond poorly to insulin-like growth factor-1: an altered signaling pathway. Mech Ageing Dev. 2000;115:21–37. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(00)00107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loeser RF, Shanker G, Carlson CS, Gardin JF, Shelton BJ, Sonntag WE. Reduction in the chondrocyte response to insulin-like growth factor 1 in aging and osteoarthritis: studies in a non-human primate model of naturally occurring disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:2110–20. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200009)43:9<2110::AID-ANR23>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerne PA, Blanco F, Kaelin A, Desgeorges A, Lotz M. Growth factor responsiveness of human articular chondrocytes in aging and development. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:960–8. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeGroot J, Verzijl N, Bank RA, Lafeber FP, Bijlsma JW, TeKoppele JM. Age-related decrease in proteoglycan synthesis of human articular chondrocytes: the role of nonenzymatic glycation. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1003–9. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199905)42:5<1003::AID-ANR20>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chubinskaya S, Kuettner KE. Regulation of osteogenic proteins by chondrocytes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35:1323–40. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(03)00035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chubinskaya S, Otten L, Soeder S, Borgia JA, Aigner T, Rueger DC, et al. Regulation of chondrocyte gene expression by osteogenic protein-1. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R55. doi: 10.1186/ar3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loeser RF, Pacione CA, Chubinskaya S. The combination of insulin-like growth factor 1 and osteogenic protein 1 promotes increased survival of and matrix synthesis by normal and osteoarthritic human articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2188–96. doi: 10.1002/art.11209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chubinskaya S, Kumar B, Merrihew C, Heretis K, Rueger DC, Kuettner KE. Age-related changes in cartilage endogenous osteogenic protein-1 (OP-1) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1588:126–34. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(02)00158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Starkman BG, Cravero JD, Delcarlo M, Loeser RF. IGF-I stimulation of proteoglycan synthesis by chondrocytes requires activation of the PI 3-kinase pathway but not ERK MAPK. Biochem J. 2005;389:723–9. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin W, Park JI, Loeser RF. Oxidative stress inhibits insulin-like growth factor-I induction of chondrocyte proteoglycan synthesis through differential regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase-Akt and MEK-ERK MAPK signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:31972–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.056838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muehleman C, Bareither D, Huch K, Cole AA, Kuettner KE. Prevalence of degenerative morphological changes in the joints of the lower extremity. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1997;5:23–37. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(97)80029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elshaier AM, Hakimiyan AA, Rappoport L, Rueger DC, Chubinskaya S. Effect of interleukin-1beta on osteogenic protein 1-induced signaling in adult human articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:143–54. doi: 10.1002/art.24151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Del Carlo M, Jr, Loeser RF. Increased oxidative stress with aging reduces chondrocyte survival: Correlation with intracellular glutathione levels. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3419–30. doi: 10.1002/art.11338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurz DJ, Decary S, Hong Y, Trivier E, Akhmedov A, Erusalimsky JD. Chronic oxidative stress compromises telomere integrity and accelerates the onset of senescence in human endothelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2417–26. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson SA, Loeser RF. Why is osteoarthritis an age-related disease? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24:15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawabata M, Miyazono K. Signal transduction of the TGF-beta superfamily by Smad proteins. J Biochem. 1999;125:9–16. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kretzschmar M, Doody J, Massague J. Opposing BMP and EGF signalling pathways converge on the TGF-beta family mediator Smad1. Nature. 1997;389:618–22. doi: 10.1038/39348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408:239–47. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henrotin YE, Bruckner P, Pujol JP. The role of reactive oxygen species in homeostasis and degradation of cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003;11:747–55. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(03)00150-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loeser RF. Aging and osteoarthritis: the role of chondrocyte senescence and aging changes in the cartilage matrix. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:971–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jallali N, Ridha H, Thrasivoulou C, Underwood C, Butler PE, Cowen T. Vulnerability to ROS-induced cell death in ageing articular cartilage: the role of antioxidant enzyme activity. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13:614–22. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruiz-Romero C, Lopez-Armada MJ, Blanco FJ. Mitochondrial proteomic characterization of human normal articular chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:507–18. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bobacz K, Gruber R, Soleiman A, Erlacher L, Smolen JS, Graninger WB. Expression of bone morphogenetic protein 6 in healthy and osteoarthritic human articular chondrocytes and stimulation of matrix synthesis in vitro. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2501–8. doi: 10.1002/art.11248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blaney Davidson EN, Scharstuhl A, Vitters EL, van der Kraan PM, van den Berg WB. Reduced transforming growth factor-beta signaling in cartilage of old mice: role in impaired repair capacity. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R1338–47. doi: 10.1186/ar1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mandal CC, Ganapathy S, Gorin Y, Mahadev K, Block K, Abboud HE, et al. Reactive oxygen species derived from Nox4 mediate BMP2 gene transcription and osteoblast differentiation. Biochem J. 2011;433:393–402. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Csiszar A, Lehoux S, Ungvari Z. Hemodynamic forces, vascular oxidative stress, and regulation of BMP-2/4 expression. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:1683–97. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]