Abstract

Repeated, intense contractile activity compromises the ability of skeletal muscle to generate force and velocity, resulting in fatigue. The decrease in velocity is thought to be due, in part, to the intracellular build-up of acidosis inhibiting the function of the contractile proteins myosin and troponin; however, the underlying molecular basis of this process remains poorly understood. We sought to gain novel insight into the decrease in velocity by determining whether the depressive effect of acidosis could be altered by 1) introducing Ca++-sensitizing mutations into troponin (Tn) or 2) by agents that directly affect myosin function, including inorganic phosphate (Pi) and 2-deoxy-ATP (dATP) in an in vitro motility assay. Acidosis reduced regulated thin-filament velocity (VRTF) at both maximal and submaximal Ca++ levels in a pH-dependent manner. A truncated construct of the inhibitory subunit of Tn (TnI) and a Ca++-sensitizing mutation in the Ca++-binding subunit of Tn (TnC) increased VRTF at submaximal Ca++ under acidic conditions but had no effect on VRTF at maximal Ca++ levels. In contrast, both Pi and replacement of ATP with dATP reversed much of the acidosis-induced depression of VRTF at saturating Ca++. Interestingly, despite producing similar magnitude increases in VRTF, the combined effects of Pi and dATP were additive, suggesting different underlying mechanisms of action. These findings suggest that acidosis depresses velocity by slowing the detachment rate from actin but also by possibly slowing the attachment rate.

Keywords: fatigue, regulation, troponin C, troponin I, 2-deoxy-ATP, phosphate

after several minutes of repeated high-intensity contraction, muscle loses much of its ability to generate force and velocity (13, 14). While the mechanisms underlying the decrease in force have been intensively investigated, the mechanisms of the depression in velocity have received less attention and are therefore still poorly understood, particularly at the molecular level (1, 25, 34).

In response to fatiguing stimulation, the maximal shortening velocity of muscle decreases by 20 to 33% (13, 14). A significant portion of this loss is believed to be due to the accumulation of hydrogen ions (i.e., acidosis) acting to directly inhibit the function of contractile proteins (9, 15, 20, 26, 35). Specifically, acidosis is thought to 1) directly slow the kinetics of the actomyosin cross-bridge cycle (16, 35) and 2) decrease the ability of calcium (Ca++) to activate the thin filament (19, 24).

Early hypotheses suggested that the decreased maximal shortening velocity in response to fatigue and the related observation of a slowed rate of relaxation were due to a slowing of the rate of cross-bridge detachment (21). Subsequent findings using skinned muscle fibers suggested a role for acidosis in this process, as it elicits a reduction in unloaded shortening velocity that is quantitatively similar to that observed during fatigue (6, 8, 35). Because the acidosis-induced decrements in velocity were observed at full Ca++ activation (i.e., pCa 4–5), it was suggested that acidosis directly inhibited the cross-bridge cycle (6, 8, 35). However, determining a direct effect at the cross-bridge level is extremely difficult within the highly complex environment of an intact muscle fiber where billions of myosin molecules interact with actin in the presence of a myriad of other proteins. Therefore, the effects of fatiguing levels of acidosis have been determined in an in vitro motility assay that used isolated myosin and actin (16). Decreasing pH from a neutral value (∼7.0) to a value experienced during fatigue (6.8–6.2) causes a sharp reduction in actin filament velocity (Vactin) in the absence of regulatory proteins, supporting the notion that acidosis directly affects myosin function (36). Our most recent work (17) suggests that acidosis slows an isomerization step in an ADP-bound state of the cross-bridge cycle (Fig. 1); however, it remains unclear whether this is the only step in the cycle affected by acidosis.

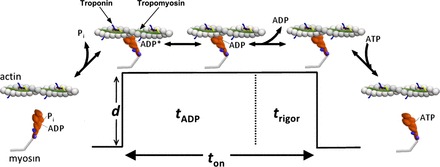

Fig. 1.

Simplified consensus model of the cross-bridge cycle. The key steps of the ATPase cycle of myosin linked to the mechanical events. The first step, inorganic phosphate (Pi) release, is linked to actin strong binding and the movement of the lever arm that results in a unitary displacement (d). During this step, tropomyosin moves over the surface of actin to allow actomyosin binding, and this is thought to be the step regulated by Ca++, i.e., the weak-to-strong transition (28). There are likely two actomyosin state with ADP bound in the active site (AM-ADP) states (60), with acidosis thought to regulate the transition from the first (AM-ADP) to the second (AM-ADP) (17). We also believe that, when Pi is elevated, the powerstroke may not be reversed, but rather myosin dissociates from actin in a postpowerstroke state to account for Pi-induced increase in regulated thin-filament velocity (VRTF) (17, 18). Thus there are likely many more steps than represented here, but for clarity we have reduced the key steps.

The other well-characterized effect of acidosis is its depressive effect on Ca++ sensitivity of the thin filament (19, 24). The limited previous investigations on shortening velocity have yielded contradictory results, with early work from the in vitro motility assay showing a significant decrease in Ca++ sensitivity (57, 58), whereas more recent work suggests that acidosis has no effect on Ca++ sensitivity (69).

The effect of acidosis on the force-pCa relationship is much less equivocal and is thought to result from acidosis directly affecting the ability of the muscle-regulatory protein troponin (Tn) to regulate and modulate the actomyosin interaction (50). One proposed mechanism suggests that acidosis affects Ca++ binding to Tn (via the Ca++-binding subunit, TnC), possibly by protons directly reducing the affinity of Ca++ for its binding site (22, 44, 50). At very low levels of Ca++ activation (>pCa 6.0), unloaded shortening velocity can be limited by the rate of cross-bridge formation (46); therefore, inhibiting Ca++ activation acidosis could also limit velocity through this mechanism. This mechanism could be particularly important in the latter stages of fatigue when Ca++ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, and thus myoplasmic [Ca++] is compromised (37).

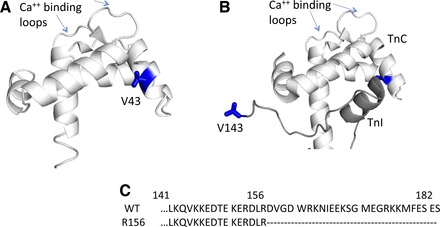

To probe the effects of acidosis mediated by Tn, we took advantage of a recently characterized mutation in TnC (V43Q) that has an increased sensitivity for Ca++ and therefore causes a leftward shift in the force-pCa relationship at neutral pH (38). The location of this mutation in Tn crystal structure is shown in Fig. 2. Based on these prior observations, we hypothesized that, if the affinity of Ca++ for TnC were increased, it might overcome the depressive effects of acidosis.

Fig. 2.

Location of mutations within troponin (Tn) structure. A: rabbit skeletal crystal structure of the NH2-terminal region of Ca++-binding subunit of Tn (TnC) shown with V43 labeled in blue, coordinates from Soman et al. (61). V43 is part of the hydrophobic patch in TnC thought to swing away from the center helix of TnC, allowing inhibitory subunit of Tn (TnI) to bind in the presence of Ca++ (73). B: TnI (dark gray) binds to the NH2-terminal of TnC (white) in the Ca++-activated state. The R156 TnI used in the present study represents a truncation mutant that eliminates the last 26 residues. The COOH terminus of TnI is not defined in the crystal structure, so the figure is truncated at residue 143. Both structural images were rendered with Polyview 3D. C: sequence of the COOH terminus of TnI for wild-type (WT) and for the TnI R156 variant illustrating the truncated residues.

A competing view of the mechanism underlying the acidosis-induced decrease in Ca++-sensitivity posits a more prominent role for the inhibitory subunit of Tn (TnI) (2, 45). Various regions of TnI may play a role mediating the effects of acidosis; however, the COOH-terminal end has received considerable attention (11, 12, 68) because it contains the region thought to interact with actin, thus maintaining tropomyosin (Tm) in a position that helps to prevent myosin from strongly binding to actin in the absence of Ca++ (65). Indeed truncation of the COOH-terminal residues beyond 156 in TnI, which is associated with the development of distal arthrogyrposis, increases contractile function in vitro, including increasing Ca++ sensitivity of force (56). Similarly, the proteolytic cleavage of the analogous region in the cardiac isoform of TnI, which occurs during myocardial ischemia, results in an increased sensitivity to Ca++ (27, 40). To explore this potential mechanism, we introduced a truncation mutant lacking a portion of the COOH-terminal end of TnI (see Fig. 2 for structural information). We hypothesized that removal of a portion of this region of TnI would weaken its affinity for actin at low Ca++ and thus would attenuate the altered Ca++ sensitivity and the depression in velocity of the thin filaments under acidic conditions.

To probe the direct effect of acidosis on the actomyosin interaction, we used two agents, inorganic phosphate (Pi) and 2-deoxy-ATP (dATP), both thought to increase the detachment rate by affecting one or more steps in the actomyosin cross-bridge cycle (Fig. 1). Elevating Pi increases the detachment rate from an actomyosin state with ADP bound in the active site (AM-ADP) by putatively reversing the Pi-release step (29) and therefore can probe the effects of shortening the lifetime of this state (29). Although less well characterized than the effects of Pi, dATP is thought to accelerate both the rate of cross-bridge formation (i.e., the weak-to-strong binding transition) and ADP release from myosin (54, 55). An effect on ADP release may be particularly relevant to fatigue because this step is thought to limit unloaded shortening velocity (47), and it is also the step thought to be slowed by acidosis (16). Therefore, we hypothesized that substituting dATP for ATP would attenuate the depressive effects of acidosis on maximal velocity in the motility assay due to both its effects on ADP release and the rate of cross-bridge formation.

By using agents that affect specific steps in the actomyosin cross-bridge cycle and by introducing Ca++-sensitizing alterations into Tn, we aimed to gain novel insight into the molecular basis of the role of acidosis in depressed contraction velocity during fatigue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Proteins.

Myosin and actin were purified from chicken pectoralis muscle as previously described (41, 49), with minor modifications described previously (18). Purified filaments were stabilized in the filamentous form and fluorescently labeled with tetramethylrodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)/phalloidin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Purified Tm was obtained from either rabbit psoas muscle or from human cardiac tissue (Life Diagnostics, West Chester, PA). Gel electrophoresis revealed that the human cardiac Tm was made up of roughly 60% of the α-isoform and 40% β-isoform, whereas the Tm from rabbit skeletal tissue was 50/50 α- and β-isoforms. Roughly half of the data were collected using each variant of Tm; however, a statistical comparison revealed that the different Tm had no effect on any of the variables tested (data not shown). Therefore, the two data sets were combined in the final analysis. The lack of a functional difference may be the result of there being similar portions of the α- and β-isoform or due to the fact that even pure isoforms of α- and β-Tm dimers fail to display differences in biological activity (53).

Wild-type Tn (WT) subunits (TnI, TnC, and TnT) were isolated from rabbit psoas muscle as previously described (63). The TnC mutant was constructed by expressing the sequence (pET-24 plasmid) for rabbit fast skeletal TnC and purified as previously described (66). The WT and R156 truncated TnI were constructed in a pET-17b plasmid, expressed and purified as previously described (39).

Solutions.

Purified myosin was diluted from a concentration of 25–35 mg/ml to 100 μg/ml in a high-salt myosin buffer (300 mM KCl, 25 mM imidazole, 1 mM EGTA, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT) before experimentation. The buffers for the motility assay were based on a lower-salt actin buffer (25 mM KCl, 25 mM imidazole, 1 mM EGTA, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT) and 2 mM ATP or 2-deoxy-ATP (Sigma-Aldrich). An oxygen-scavenging system was also added to prevent photobleaching of the actin filaments (57 mg glucose, 2.5 mg glucose oxidase, and 0.45 mg catalase), and methylcellulose (1% vol/vol) was added to these buffers to keep the filaments near the coverslip surface.

Buffer recipes were determined using WinMaxC (52). The total ionic strength of each solution was held constant at 95 mM in each condition by adjusting the amount of KCl added to the final motility buffer. It is important to note that the computer program for determining solution composition (52) takes into account the strong pH dependence of the chelating capacity of EGTA (3). The pH of the assay buffers was set to 7.4, 6.8, or 6.5 by manipulating added HCl. To simulate fatigue conditions, we added Pi, which, to maintain the total ionic strength at 95 mM, the Pi concentration was set to 15 mM. The Ca++ concentration under each condition was varied from pCa 10 to pCa 5, carefully considering the pH dependence of the Ca++-binding affinities to all the other constituents in the solution.

In vitro motility assay.

In vitro motility assays with reconstituted thin filaments were performed as previously described (17) using the equipment detailed in Debold et al. (18), with minor modifications. Briefly, myosin was loaded onto a nitrocellulose-coated coverslip surface at a saturating concentration of 100 μg/ml. This was followed by 0.5 mg/ml BSA to block any uncoated areas of the coverslip surface from interacting with actin. TRITC-labeled actin filaments were added to the flow cell in the absence of ATP but in the presence of 0.25 μM Tm and 0.75 μM Tn and incubated in the flowcell for 7 min to reconstitute regulated thin filaments, as previously detailed (32). The final assay buffer contained an additional 100 nM Tn and 100 nM Tm to ensure that the filaments remained fully regulated during experimentation (31). Reconstituted thin-filament motion was visualized using a Nikon Ti-U inverted microscope, with a ×100, 1.4 NA CFI Plan Apo oil-coupled objective with the temperature maintained at 30.0°C for all experiments. For each flow cell, three 30-s videos were captured at 10 frames/s and at three different locations within each flow cell.

Video analysis.

The velocity of the reconstituted thin filaments was determined using an automated filament-tracking software program (CellTrak; MotionAnalysis, Santa Rosa, CA), as previously described for regulated thin filaments (30, 69). In an effort to eliminate the possibility of analyzing noise in the fluorescence signal, filaments <0.5 μm were eliminated from the analysis, and filaments with velocities <0.13 μm/s were considered to be stationary. A typical field of view generated 25–75 filament velocities, and the mean of these velocities was taken as the average velocity for a given field of view. The microscope slide was then moved to a new field of view within the flow cell twice more to generate a total of three recordings for each flow cell. For each condition tested, three to eight flow cells were used to generate the data, resulting in a total of 9–24 recordings contributing to the overall mean filament velocity for each condition.

Statistical analyses.

Filament velocity at each pCa level was plotted and fit with a Hill equation: V = Vmax/[1 + 10n(pCa50 −pCa)], where V is the average RTF velocity, Vmax is the maximum velocity, n is the Hill coefficient, and pCa50 is the free [Ca++] (in -log units) at which RTF velocity is half the maximum value. The curve fits to the data were generated for the velocity vs. pCa relationship using a curve-fitting routine within SigmaPlot 11.2 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA). Goodness-of-fit was evaluated using the R2 value.

The data set of each day was fit separately to the above equation to generate individual parameters from the fits and the derived values used for inferential statistics, a methodology previously suggested as the optimum approach for comparing differences in the force or velocity-pCa relationships (28). The differences between maximal VRTF and the parameters of the Hill fit were quantified using a two-way ANOVA, and a Tukey's post hoc test was used to locate the differences. The effect of 15 mM Pi and dATP on the velocity-pCa relationship of filaments with WT Tn was determined by comparing the parameters of the Hill fit using a two-way ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc tests. To compare the combined effects of the 15 mM Pi and dATP on maximal VRTF velocities for filaments reconstituted with WT Tn, the data were analyzed using a three-way ANOVA (pH × Pi × ATP type) with specific differences located using Tukey's post hoc tests. All inferential statistics were performed in SigmaPlot/SigmaStat version 11.2, and the α-level for all statistical tests was set at 0.05.

RESULTS

Decreasing the pH from 7.4 to 6.8 caused a large reduction in VRTF at both saturating and subsaturating Ca++ concentrations (Fig. 3). Decreasing the pH further to 6.5 caused even larger reductions in VRTF at all [Ca++] from pCa 7.0 to 4.0 (Fig. 4), with the maximal velocity reaching only ∼10% of the maximum value. In fact, VRTF (0.21 ± 0.08 μm/s) at pH 6.5, even at saturating Ca++ levels (pCa 4 and 5), was not significantly different from the threshold used to define filaments as moving (0.13 μm/s). At pH 6.8 most of the reduction in VRTF occurred at saturating [Ca++], with little effect on the pCa50 (Table 1). In contrast, lowering the pH further to 6.5 caused a very dramatic rightward shift in the velocity-pCa relationship, resulting in a greater than two-unit change in the pCa50 value (Table 2). In fact, the severity of the acidosis-induced depression in velocity likely contributed to the data being poorly fit (R2 = 0.22) by the Hill equation.

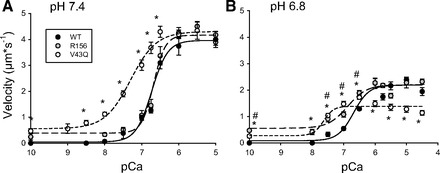

Fig. 3.

Effect of mutations in Tn on velocity-pCa relationship at different pH. VRTF determined at normal (7.4) and low pH (6.8) using filaments reconstituted with WT Tn, Tn with a V43Q mutation in TnC, and Tn with TnI truncated beyond R156. VRTF plotted as a function of the -log of the [Ca++] (pCa). Data points represent means ± SE. Data were fit with Hill equation with fit parameters displayed in Table 1. *VRTF with V43Q is significantly different from control at the given pCa value. #VRTF with R156 is significantly different from control at the given pCa value.

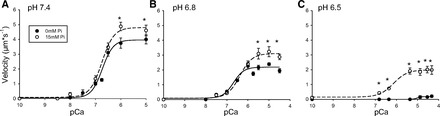

Fig. 4.

A–C: effect of 15 mM Pi on the velocity-pCa relationship at different pH. VRTF with WT Tn plotted as a function of the pCa and pH in the presence and absence of 15 mM Pi. Data points represent means ± SE. Data were fit with Hill equation with fit parameters displayed in Table 2. *VRTF with 15 mM Pi is significantly different from control at the given pCa value.

Table 1.

Parameter estimates of the Hill fits to velocity-pCa data

| pH | Tn | pCa50 | Hill | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.4 | WT | 6.71 ± 0.07 | 2.02 ± 0.37 | 0.86 |

| R156 | 6.76 ± 0.11 | 2.76 ± 0.49 | 0.82 | |

| V43Q | 7.26 ± 0.08* | 1.24 ± 0.17 | 0.84 | |

| 6.8 | WT | 6.71 ± 0.07 | 1.76 ± 0.45 | 0.82 |

| R156 | 6.78 ± 0.01 | 1.43 ± 0.41 | 0.80 | |

| V43Q | 7.59 ± 0.18* | 2.72 ± 1.36 | 0.55 |

Values represent means ± SE for filaments reconstituted with wild-type (WT) troponin (Tn), Tn with a V43Q mutation in Ca++-binding subunit of Tn (TnC) or Tn with the inhibitory subunit of Tn (TnI) truncated beyond residue 156.

Significantly different from WT.

Table 2.

Parameter estimates from Hill fits to velocity-pCa data for the effect of Pi

| pH | Pi | pCa50 | Hill | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.4 | 0 | 6.71 ± 0.07 | 2.02 ± 0.37 | 0.86 |

| 15 | 6.75 ± 0.04 | 1.83 ± 0.33 | 0.90 | |

| 6.8 | 0 | 6.71 ± 0.07 | 1.76 ± 0.45 | 0.83 |

| 15 | 6.34 ± 0.26 | 1.49 ± 0.46 | 0.81 | |

| 6.5 | 0 | 4.55 ± 0.24* | 4.57 ± 12.1 | 0.22 |

| 15 | 6.24 ± 0.18† | 1.32 ± 0.63 | 0.67 |

Values represent means ± SE for filaments reconstituted with WT Tn.

Significantly different from pH 7.4 and 0 mM inorganic phosphate (Pi). †Significantly different from 0 mM Pi at pH 6.5.

Introducing the V43Q Ca++-sensitizing mutation into TnC increased VRTF compared with filaments with WT Tn at every submaximal [Ca++] from pCa 10 to 6.5 and at both high (7.4) and low pH (6.8) (Fig. 3). At pH 6.8, this resulted in an increase of 0.8 pCa units in the pCa50 value compared with WT filaments (Table 1), suggesting that the mutation increased the Ca++ sensitivity for velocity. This effect occurred at both pH 7.4 and 6.8, indicating that it was pH independent. It is important to note that, although the presence of this mutation increased the Ca++ sensitivity, acidosis still significantly decreased VRTF at every pCa level from 10.0 to 4.5 (Fig. 3). This suggests that the mutation did not reverse the depressive effect of acidosis despite sensitizing the filaments to Ca++. We attempted to determine the effect at pH 6.5; however, the depression in VRTF at pH 6.5 was so severe that a reasonable fit to the velocities with the Hill equation could not be generated (data not shown).

It is important to point out that, whereas filaments reconstituted with WT Tn did not move in the absence of Ca++ (pCa 10, Fig. 3), some intermittent filament motion was detected for the filaments reconstituted with the V43Q TnC mutation (Fig. 3). This represented only a small percentage (∼3%) of the total filaments, but it suggests a decreased ability to regulate actomyosin binding even in the absence of Ca++.

Regulated thin filaments reconstituted with the truncated form of TnI (R156) responded nearly identically to filaments with WT Tn to increases in [Ca++] at pH 7.4, with no difference in any VRTF from 10.0 to 5.0 (Fig. 3). However, at pH 6.8 the filaments with truncation at R156 moved significantly faster than the filaments with WT TnI at subsaturating [Ca++] (pCa 7.5, 7.0, and 6.5, see Fig. 3), indicating a pH-dependent response to increases in Ca++. The presence of the truncated TnI did not, however, alter the strong depressive effect of acidosis (pH 7.4 vs 6.8) at saturating Ca++ (e.g., pCa 5.0), where the depression was similar to that observed for filaments with WT TnI (Fig. 3). Despite the individual differences at specific subsaturating [Ca++], the value for the pCa50 was, like filaments with WT TnI, not affected by the decrease in pH from 7.4 to 6.8 (Table 1). We attempted to obtain filament velocities with this construct at pH 6.5, but, like the V43Q TnC mutation, the measureable velocities were so slow that reasonable fits to the Hill equation could not be obtained (data not shown).

Influence of Pi and dATP on VRTF.

Acidosis had the strongest effect on VRTF at saturating Ca++ levels (Fig. 4), suggesting that much of the depression in velocity was due to a direct effect on the actomyosin interaction. To test this idea, we sought to directly perturb actomyosin interaction using agents that alter myosin function. Our first candidate was Pi because it is thought to have little or no direct effect on Tn (48) but induces the detachment of myosin from actin in the strongly bound state (18, 29).

Indeed, at pH 7.4 the addition of 15 mM Pi increased VRTF by 10% at saturating Ca++ levels but did not alter VRTF at subsaturating Ca++ (Fig. 4). This is quantitatively similar to the 7% increase we observed previously using cardiac Tn (17) although in the present study it reached statistical significance. The effect was stronger at pH 6.8, where Pi increased VRTF by 25% at saturating Ca++ levels (pCa 5.5 to 4.5) but, again, had no effect on VRTF at subsaturating Ca++ (Fig. 4). This Pi-induced increase in VRTF was even more pronounced at pH 6.5, where VRTF increased roughly 10-fold (Fig. 4), which is also qualitatively consistent with our previous observations using cardiac Tn (17). In fact, at subsaturating Ca++ levels, where filaments exhibited no velocity in the absence of Pi, they began to move in the presence of the Pi. For example, at pCa 5.25, filaments went from displaying zero movement in the absence of Pi to near maximal velocity in the presence of Pi. This latter result caused the acidosis-induced depression in pCa50 at pH 6.5 to be reversed by almost 2 pCa units (Table 2).

Replacing the ATP with dATP at pH 7.4 did not affect VRTF at low Ca++ levels but significantly increased it from pCa 7.0 to 6.5 (Fig. 5), reaching a maximum of threefold at pCa 6.75 and representing an 18% increase at pCa 6.5. dATP also influenced the shape of the velocity-pCa relationship, resulting in a doubling of the steepness of the relationship, evidenced by the change in the Hill coefficient (Table 3). The effects of dATP at saturating [Ca++] were qualitatively similar at pH 6.8 and 6.5 but larger in magnitude; in fact at pH 6.5 VRTF changed from zero at low Ca++ levels to near maximal values in the presence of dATP. This drastic increase in VRTF caused by dATP attenuated the depressive effect of acidosis on the pCa50 value, increasing it by ∼2 pCa units at pH 6.5 (Table 3).

Fig. 5.

A–C: effect of 2-deoxy ATP (dATP) of the velocity-pCa relationship at different pH. VRTF with WT Tn plotted as a function of the pCa and pH in the presence of dATP. Data points represent means ± SE. Data were fit with Hill equation with fit parameters displayed in Table 3. *VRTF with dATP is significantly different from control at the given pCa value.

Table 3.

Parameter estimates from Hill fits to velocity-pCa data for the effect of dATP

| pH | ATP | pCa50 | Hill | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.4 | normal | 6.71 ± 0.07 | 2.02 ± 0.37 | 0.86 |

| 2-deoxy | 6.95 ± 0.06 | 4.31 ± 1.43 | 0.87 | |

| 6.8 | normal | 6.71 ± 0.07 | 1.76 ± 0.45 | 0.83 |

| 2-deoxy | 6.52 ± 0.02‡ | 4.47 ± 2.01 | 0.88 | |

| 6.5 | normal | 4.55 ± 0.24†* | 4.57 ± 12.1 | 0.22 |

| 2-deoxy | 6.30 ± 0.03‡ | 4.09 ± 2.84 | 0.77 |

Values represent means ± SE for filaments reconstituted with WT Tn.

Indicates significantly different from pH 6.5 in 2-deoxy ATP (dATP). †Indicates significantly different from pH 7.4 and 6.8 with normal ATP.

Indicates significantly different from pH 7.4 in dATP.

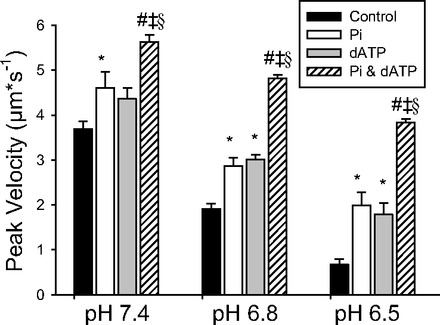

In a separate set of experiments we systematically determined the effects of pH, dATP, and elevated Pi on VRTF at saturating Ca++ levels (pCa 5.0). The magnitude of the increases in VRTF induced by Pi and dATP at saturating Ca++ levels were strikingly similar across all pH levels (Fig. 6). This suggested that the underlying mechanisms might be similar; therefore, we examined the combined effect of both of these changes on maximal VRTF in a separate set of experiments. Interestingly, the combined effects were much greater than those of either Pi or dATP when added alone (Fig. 6). A three-way ANOVA (pH × ATP type × Pi) revealed that the effect of dATP was dependent on both pH and the presence of Pi. Specifically, the effect of dATP was significantly greater at the lower pH levels (6.8 and 6.5) then at pH 7.4. This is most evident when comparing the extremes of pH; for example, changing ATP for dATP increased VRTF by only 18% (ns) at pH 7.4 but almost doubled VRTF at pH 6.5.

Fig. 6.

Effect of pH, Pi, and dATP on WT VRTF. VRTF for filaments reconstituted with WT Tn at pCa 5.0 as a function of pH, in the presence and absence of 15 mM Pi, and dATP. Values represent means ± SE and were analyzed using a 3-way ANOVA. All pairwise comparisons were significant except the effect of Pi (open bar) vs. dATP (shaded bar) at each pH level. *Significantly different from control; #significantly different from Pi condition; ‡significantly different from dATP condition. The interactions for pH × ATP type and Pi by ATP type were both significant (P < 0.05), indicated by §, but the Pi × pH interaction only trended toward significance (P = 0.07). The 3-way interaction (pH × Pi × ATP type) was not significant (P = 0.564).

The significant interaction between ATP × Pi indicates that the magnitude of the effect of dATP on VRTF depends on the presence of Pi. These findings, therefore, suggest that the combined effects of dATP and Pi may not be solely attributed to an additive effect, implying the existence of a synergistic component to the effects of Pi and dATP. Thus it is clear that these two agents do not have the same effect on VRTF but rather act independently and possibly synergistically to increase VRTF.

In this ANOVA, the three-way interaction was not significant, indicating that interaction between Pi and type of ATP was not dependent on the pH. This implies that any synergy between Pi and dATP was similar in magnitude at each pH. In addition, post hoc tests revealed that the drop in pH caused a significant depression in VRTF under every condition, suggesting that acidosis caused a depression in VRTF even in the presence of Pi or dATP, either separately or in combination.

DISCUSSION

The accumulation of H+ (i.e., acidosis) is thought to play a significant role in the process of skeletal muscle fatigue, in part, by reducing the velocity of contraction. Acidosis is thought to decrease velocity by slowing the kinetics of the cross-bridge cycle and decreasing the sensitivity of the thin filaments to Ca++ (15, 26). In the present investigation, we probed 1) the direct effect on the cross-bridge by using Pi and dATP to alter the kinetics of the actomyosin interaction, and 2) the effect on Ca++ sensitivity by introducing Ca++-sensitizing mutations into Tn. Both Pi and dATP increased VRTF at saturating [Ca++], and both variants of Tn enhanced VRTF at subsaturating Ca++ levels under acidic conditions but to a lesser extent than Pi and dATP. Exploration of the mechanisms underlying these effects provides potentially novel insights into the molecular basis of the depressive effects of acidosis experienced during muscle fatigue.

Pi and dATP can reverse the acidosis-induced depression in VRTF.

The most pronounced effect of acidosis in the present study was the large depression in VRTF at saturating Ca++ levels (Fig. 4). This suggests that much of the depression in velocity was due to a direct effect on the actomyosin interaction. This notion is supported by the observation that elevating Pi increased VRTF at saturating Ca++ levels in a pH-dependent manner (Fig. 4). We have previously observed this same phenomenon using cardiac isoforms of Tn at twice the Pi concentration (17) and postulated that it is likely due to Pi rebinding to actomyosin in an ADP-bound state and inducing dissociation from a postpowerstroke state (18). The fact that we observe a similar response at 15 and 30 mM Pi suggests that the effect of Pi on VRTF is saturated below 15 mM.

The pH dependence of this effect, we have postulated, results from acidosis slowing the rate of ADP release from actomyosin, prolonging the AM-ADP state (16, 18). Prolongation of this AM-ADP state means that the cross-bridge spends more time in the AM-ADP state, which is the state vulnerable to Pi rebinding (74); therefore the Pi-induced increase in VRTF is more pronounced at lower pH levels (see Fig. 1 for cross-bridge model). Thus the present data provide additional support for this hypothesis and demonstrate that the same effect is produced when an actin filament is reconstituted with fast skeletal Tn as with cardiac Tn.

An alternative hypothesis is that the increase in Pi increases the population of weakly bound AM-ADP Pi heads, putatively increasing the activation level of the thin filament. Indeed there is evidence to indicate that this can occur based on X-ray diffraction experiments in single fibers (5) and solution experiments on isolated thin filaments in the presence of weakly bound myosin S1 (42). On the basis of this mechanism, elevated Pi should have increased the attachment rate, and thus VRTF, at low [Ca++]. However, Pi did not enhance velocity at low Ca++ levels at any pH (Fig. 4). Therefore, this effect, if acting in the present study, was not pronounced enough to affect our results. The much stronger effect of Pi was observed at saturating Ca++, which is consistent with Pi increasing the detachment rate rather than affecting the attachment rate.

We also probed the direct effect of acidosis on the actomyosin interaction by substituting dATP for ATP in our buffers. This substrate was used because it has previously been shown to increase unregulated and regulated thin-filament velocity at neutral pH, and, unlike Pi, it does so without decreasing the force-generating capacity of muscle (55). In fact, dATP can even increase the force-generating capacity of isolated myosin (7). We did not observe an increase in VRTF at pH 7.4, which contrasts with the increases observed previously (55), but this is likely due to the fact that the dATP-induced increases in filament velocity are dependent on the presence of regulatory proteins on the thin filament (7). More importantly, we show for the first time that dATP can also significantly increase VRTF under acidic conditions, recovering roughly 50% of the loss in VRTF caused by decreasing the pH to 6.5 (Figs. 5 and 6). In fact, the enhancement of VRTF was significantly greater at pH 6.5 and 6.8 vs. pH 7.4, indicating that the magnitude of the effect of dATP is dependent on pH. Interestingly, the magnitude and the pH dependence of the increase in VRTF caused by dATP at saturating [Ca++] was quite similar to the effect caused by Pi (Fig. 6). This suggested that Pi and dATP might be acting through a similar mechanism; however, when both were combined, they had a largely additive effect on VRTF, suggesting that they act through distinctly different mechanisms, a notion more consistent with previous findings. For example, Pi is thought to increase VRTF by preferentially rebinding to actomyosin in an AM-ADP state before the state from which ADP is released (the AM-ADP state) (10, 64, 74). Once rebound to Pi, myosin quickly dissociates from a post-power stoke state, thereby reducing the strongly bound lifetime and thus increasing VRTF (17, 18). In contrast, dATP is thought to increase both the weak-to-strong binding transition (54, 55). An increased rate of the weak-to-strong binding transition could underlie the strong effect of dATP that persists in the presence of 15 mM Pi (Fig. 6). Assuming that at 15 mM Pi the effect on the detachment rate is saturated, as is the case for the effect of Pi on force (51), only an increase in the attachment rate (i.e., weak-to-strong binding) could enable VRTF to be increased in the additive manner observed (Fig. 6). This would suggest that acidosis, not only slows the detachment rate, but also slows the rate of cross-bridge attachment (i.e., the weak-to-strong binding transition). The slowed attachment rate could result from a slowing of any step in the cross-bridge cycle subsequent to ATP-induced dissociation to a step immediately before the formation of the strong binding to actin. This would certainly include the step involving the hydrolysis of ATP, which we have previously hypothesized is slowed by acidosis (16).

The increase in VRTF could also be due to an increased rate of dADP release from myosin because this is thought to be the step that limits unloaded shortening velocity (47, 59, 75). The increased rate of ADP release may result from the subtle structural alterations to ATP reducing the affinity of myosin for dADP hastening its release from actomyosin and consequently increasing velocity (55). Paradoxically, speeding the release of ADP from the AM-ADP state might be expected to decrease the number of strongly attached cross-bridges and thus force; however, this effect must be compensated for by the increased rate of the transition from weak-to-strong binding to maintain or even increase force (54).

The increased rate of weak-to-strong binding might also explain the distinctly different effect dATP had on the shape of velocity-pCa relationship compared with Pi (Fig. 5). For example, dATP increased the steepness of the curve evidenced by an increase in the Hill coefficient. This effect likely contributed to restoration of the pCa50 value at pH 6.5 from 4.55 to 6.30 (Table 3). This increase in the weak-to-strong binding transition would increase the number of strongly bound cross-bridges, which in turn would enhance the activation of the thin filament via strong binding (28). If the increased rate of the weak-to-strong transition underlies our observations, it would be consistent with previous findings demonstrating that dATP can speed the overall rate of ATP hydrolysis (55) and increase maximal isometric force in muscle fibers (7).

Regulatory proteins play a minor role in the acidosis-induced depression of VRTF.

We found that acidosis decreases VRTF at both subsaturating and saturating Ca++ concentrations in a manner that is qualitatively similar to previous observations using cardiac isoforms of Tn (17, 57, 58, 69). This similarity was somewhat unexpected based on previous findings showing that acidosis can have a more pronounced effect on the Ca++ sensitivity of force in cardiac vs. skeletal muscle (2). This may be due the differential factors regulating force and velocity as discussed below and suggests that, unlike force, the structural differences between cardiac and skeletal Tn do not seem to dictate the acidosis sensitivity of VRTF in vitro.

With the use of WT skeletal Tn, decreasing the pH from 7.4 to 6.8 did not significantly alter the apparent value for pCa50, suggesting that the Ca++ sensitivity was not altered; however, at certain subsaturating [Ca++], the decrease in velocity was significant (Fig. 3). Therefore, the decrease in the apparent value for pCa50 may not fully reflect that acidosis had a depressive effect on the ability of Ca++ to bind to TnC and activate the thin filament. Indeed decreasing the pH to 6.5 elicited a more pronounced rightward shift in the velocity pCa (Fig. 3). This finding suggests that acidosis does indeed decrease the Ca++ sensitivity of VRTF but that it requires the pH to be below 6.8 to elicit a significant change in the apparent pCa50.

The present findings are consistent with acidosis primarily slowing the detachment rather than the attachment rate because elevated Pi, which increases the detachment rate (64), reversed much of the acidosis-induced depression in VRTF (Fig. 4). This is further supported by the observation that filaments reconstituted with the Ca++-sensitizing variants of Tn (Fig. 2) and WT Tn filaments responded similarly to decreasing pH and had no effect on the pronounced depression in VRTF at saturating Ca++ levels.

The actomyosin detachment rate may not, however, be the only factor governing filament velocity, particularly at low Ca++ levels. Filaments reconstituted with both the V43Q mutation in TnC and the truncated variant of TnI (R156) showed increased VRTF at subsaturating Ca++ levels at low pH compared with filaments with WT Tn (Fig. 3). For example, filaments reconstituted with the V43Q TnC mutation demonstrated an apparent increase in Ca++ sensitivity compared with filaments with WT Tn under normal pH and retained this increase at pH 6.8. The increased velocity at subsaturating Ca++ suggests that the filament experienced a greater level of activation at any given subsaturating [Ca++], which would lead to more cross-bridges attaching to and moving the thin filament. This is consistent with previous work in muscle fibers demonstrating that at low [Ca++] (typically pCa 6.0 or below) unloaded shortening velocity can be limited by the rate of cross-bridge attachment (46). Therefore, the increased velocity at subsaturating conditions suggests that acidosis also affects the attachment rate of myosin at low [Ca++].

However, it is important to note that acidosis still significantly depressed VRTF in the presence of this mutation (V43Q). This finding suggests that, although the mutation to TnC sensitizes the filaments to Ca++, it does not reverse the effects of acidosis and implies that this amino acid is not involved in the putative mechanism that allows acidosis to affect the ability of Ca++ to bind to TnC (23, 50).

In contrast, the small but significant increase in VRTF at subsaturating [Ca++] observed for filaments reconstituted with the truncated TnI (R156) was only observed at low pH (Fig. 3). Indeed at pCa 7.5 VRTF was significantly greater under acidic conditions vs. normal pH for this construct (Fig. 3). These observations indicate a pH-dependent effect on VRTF and suggest that the final 26 residues of fast skeletal TnI contain a pH-sensitive domain. Again, at the cross-bridge level, this increase in VRTF at subsaturating Ca++ could be due to either an increase in the rate of weak-to-strong binding transition of myosin (i.e., cross-bridge formation) or an increased rate of detachment of myosin from the strongly bound state (for model see Fig. 1). If the increase were due to an acceleration of the rate of detachment of myosin, then we would have expected VRTF to also be increased at saturating Ca++ levels with this variant of TnI, but this was not evident in the data (Fig. 3). Therefore, the findings suggest that the increase in VRTF at subsaturating Ca++ is due to an increase in the rate of the weak-to-strong binding transition.

At the molecular level, the removal of the final 26 residues may weaken the contacts of TnI with actin and thus weaken the inhibition of actomyosin binding in the absence of Ca++ (65). Further support for this notion comes from the observation that filaments with R156 TnI are not completely stopped in the absence of Ca++ (Fig. 3). However, our findings suggest that this would have to occur in a pH-dependent manner.

Thus, although the major effect of acidosis is on the actomyosin interaction, the findings from these mutations suggest that, at subsaturating levels of Ca++, there is a small but potentially important role for Tn in the acidosis-induced decrease in VRTF.

Comparison with the effects on the force-pCa relationship.

The rightward shift in the velocity-pCa relation we observed at pH 6.5 is qualitatively similar to the acidosis-induced rightward shift in the force-pCa relationship seen by others (19, 24, 48, 50). However, isometric force (71) and unloaded shortening velocity (67) are thought to be governed by distinctly different steps in the cross-bridge cycle (67, 70); thus it is likely that distinctly different mechanisms underlie the rightward shift in the velocity-pCa relationship observed in the present study.

Maximal isometric force is thought to be limited by the force per cross-bridge and the duty cycle of myosin (i.e., percent of the ATPase cycle spent strongly bound to actin) (72). Although there is some evidence to suggest that acidosis may decrease the force per cross-bridge (43), most evidence suggests that the rightward shift in the force-pCa relationship is predominantly caused by decreased activation of the thin filament (19, 44, 48, 50). By inhibiting activation of the thin filament, force is reduced due to a slowing of the rate at which myosin progresses from a weakly to strongly bound state, leading to a decrease in the number of force-generating cross-bridges (4, 28). In contrast, unloaded shortening velocity is thought to be most strongly governed by the rate of detachment of myosin from actin, rather than the weak-to-strong binding rate (33, 67). Thus it appears that, even though acidosis produces a similar rightward shift in the force and velocity-pCa relationships, the underlying mechanisms of the two effects are likely distinctly different.

It is of course possible that these mechanisms may overlap due to the ability of myosin strong binding to influence thin-filament activation (62). For example, increasing the detachment rate would decrease the number of strongly bound cross-bridges and thus decrease thin-filament activation. This decrease in thin-filament activation would lead to a slowing of the rate of attachment of subsequent cross-bridges (i.e., negative cooperativity), which should be reflected in the Hill coefficient (n). However, in the present data, acidosis did not have a significant effect on n (Table 1), suggesting that a change in the cooperative binding does not play a major role in the acidosis-induced depression of VRTF.

Conclusions.

The most pronounced effect of acidosis occurred at saturating Ca++ levels, suggesting that it slows VRTF through a direct effect on the actomyosin interaction. Much of this effect can be attenuated by either increasing the detachment rate and/or increasing the rate of the weak-to-strong binding transition with Pi and dATP. To a much lesser extent, the acidosis-induced decrease in VRTF may be mediated by an effect on Tn because Ca++-sensitizing variants of Tn attenuated some of the decrease in filament velocity but only at subsaturating Ca++ levels.

GRANTS

This work was supported by an AHA Scientist Development Grant (09SDG2100039) to E. Debold.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: T.J.L., J.P.D., J.L., B.J.B., and E.P.D. conception and design of research; T.J.L., M.A.T., and J.L. performed experiments; T.J.L., M.A.T., and E.P.D. analyzed data; T.J.L., M.A.T., J.P.D., B.J.B., and E.P.D. interpreted results of experiments; T.J.L. and E.P.D. prepared figures; T.J.L. and E.P.D. drafted manuscript; T.J.L., J.P.D., B.J.B., and E.P.D. edited and revised manuscript; T.J.L., M.A.T., J.P.D., J.L., B.J.B., and E.P.D. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen DG. Fatigue in working muscles. J Appl Physiol 106: 358–359, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball KL, Johnson MD, Solaro RJ. Isoform specific interactions of troponin I and troponin C determine pH sensitivity of myofibrillar Ca2+ activation. Biochemistry 33: 8464–8471, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bers DM, Patton CW, Nuccitelli R. A practical guide to the preparation of Ca2+ buffers. Methods Cell Biol 40: 3–29, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner B. Effect of Ca2+ on cross-bridge turnover kinetics in skinned single rabbit psoas fibers: Implications for regulation of muscle contraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85: 3265–3269, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner B, Schoenberg M, Chalovich JM, Greene LE, Eisenberg E. Evidence for cross-bridge attachment in relaxed muscle at low ionic strength. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 79: 7288–7291, 1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chase PB, Kushmerick MJ. Effects of pH on contraction of rabbit fast and slow skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys J 53: 935–946, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clemmens EW, Regnier M. Skeletal regulatory proteins enhance thin filament sliding speed and force by skeletal HMM. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 25: 515–525, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooke R, Franks K, Luciani GB, Pate E. The inhibition of rabbit skeletal muscle contraction by hydrogen ions and phosphate. J Physiol 395: 77–97, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtin NA, Edman KA. Force-velocity relation for frog muscle fibres: effects of moderate fatigue and of intracellular acidification. J Physiol 475: 483–494, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dantzig JA, Goldman YE, Millar NC, Lacktis J, Homsher E. Reversal of the cross-bridge force-generating transition by photogeneration of phosphate in rabbit psoas muscle fibres. J Physiol 451: 247–278, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Day SM, Westfall MV, Fomicheva EV, Hoyer K, Yasuda S, La Cross NC, D'Alecy LG, Ingwall JS, Metzger JM. Histidine button engineered into cardiac troponin I protects the ischemic and failing heart. Nat Med 12: 181–189, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Day SM, Westfall MV, Metzger JM. Tuning cardiac performance in ischemic heart disease and failure by modulating myofilament function. J Mol Med 85: 911–921, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Ruiter CJ, Jones DA, Sargeant AJ, de HA. The measurement of force/velocity relationships of fresh and fatigued human adductor pollicis muscle. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 80: 386–393, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de HA, Jones DA, Sargeant AJ. Changes in velocity of shortening, power output and relaxation rate during fatigue of rat medial gastrocnemius muscle. Pflügers Arch 413: 422–428, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Debold EP. Recent insights into muscle fatigue at the cross-bridge level. Front Physiol 3: 151, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Debold EP, Beck SE, Warshaw DM. The effect of low pH on single skeletal muscle myosin mechanics and kinetics. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C173–C179, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Debold EP, Longyear TJ, Turner MA. The effects of phosphate and acidosis on regulated thin filament velocity in an in vitro motility assay. J Appl Physiol 113: 1413–1422, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Debold EP, Turner MA, Stout JC, Walcott S. Phosphate enhances myosin-powered actin filament velocity under acidic conditions in a motility assay. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 300: R1401–R1408, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donaldson SK, Hermansen L, Bolles L. Differential, direct effects of H+ on Ca2+-activated force of skinned fibers from the soleus, cardiac and adductor magnus muscles of rabbits. Pflügers Arch 376: 55–65, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edman KA, Mattiazzi AR. Effects of fatigue and altered pH on isometric force and velocity of shortening at zero load in frog muscle fibres. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 2: 321–334, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards RH, Hill DK, Jones DA. Metabolic changes associated with the slowing of relaxation in fatigued mouse muscle. J Physiol 251: 287–301, 1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.el-Saleh SC, Solaro RJ. Troponin I enhances acidic pH-induced depression of Ca2+ binding to the regulatory sites in skeletal troponin C. J Biol Chem 263: 3274–3278, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engel PL, Kobayashi T, Biesiadecki B, Davis J, Tikunova S, Wu S, Solaro RJ. Identification of a region of troponin I important in signaling cross-bridge-dependent activation of cardiac myofilaments. J Biol Chem 282: 183–193, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fabiato A, Fabiato F. Effects of pH on the myofilaments and the sarcoplasmic reticulum of skinned cells from cardiace and skeletal muscles. J Physiol 276: 233–255, 1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fitts RH. Cellular mechanisms of muscle fatigue. Physiol Rev 74: 49–94, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fitts RH. The cross-bridge cycle and skeletal muscle fatigue. J Appl Physiol 104: 551–558, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foster DB, Noguchi T, VanBuren P, Murphy AM, Van Eyk JE. C-terminal truncation of cardiac troponin I causes divergent effects on ATPase and force: implications for the pathophysiology of myocardial stunning. Circ Res 93: 917–924, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gordon AM, Homsher E, Regnier M. Regulation of contraction in striated muscle. Physiol Rev 80: 853–924, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hibberd MG, Dantzig JA, Trentham DR, Goldman YE. Phosphate release and force generation in skeletal muscle fibers. Science 228: 1317–1319, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Homsher E, Kim B, Bobkova A, Tobacman LS. Calcium regulation of thin filament movement in an in vitro motility assay. Biophys J 70: 1881–1892, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Homsher E, Lee DM, Morris C, Pavlov D, Tobacman LS. Regulation of force and unloaded sliding speed in single thin filaments: effects of regulatory proteins and calcium. J Physiol 524: 233–243, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Homsher E, Nili M, Chen IY, Tobacman LS. Regulatory proteins alter nucleotide binding to acto-myosin of sliding filaments in motility assays. Biophys J 85: 1046–1052, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huxley HE. Sliding filaments and molecular motile systems. J Biol Chem 265: 8347–8350, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones DA. Changes in the force-velocity relationship of fatigued muscle: implications for power production and possible causes. J Physiol 588: 2977–2986, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knuth ST, Dave H, Peters JR, Fitts RH. Low cell pH depresses peak power in rat skeletal muscle fibres at both 30 degrees C and 15 degrees C: implications for muscle fatigue. J Physiol 575: 887–899, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kron SJ, Spudich JA. Fluorescent actin filaments move on myosin fixed to a glass surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 83: 6272–6276, 1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JA, Westerblad H, Allen DG. Changes in tetanic and resting [Ca2+]i during fatigue and recovery of single muscle fibres from Xenopus laevis. J Physiol 433: 307–326, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee RS, Tikunova SB, Kline KP, Zot HG, Hasbun JE, Minh NV, Swartz DR, Rall JA, Davis JP. Effect of Ca2+ binding properties of troponin C on rate of skeletal muscle force redevelopment. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299: C1091–C1099, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Little SC, Tikunova SB, Norman C, Swartz DR, Davis JP. Measurement of calcium dissociation rates from troponin C in rigor skeletal myofibrils. Front Physiol 2: 70, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu B, Lee RS, Biesiadecki BJ, Tikunova SB, Davis JP. Engineered troponin C corrects disease-related cardiac myofilament calcium sensitivity. J Biol Chem 287: 20027–20036, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Margossian SS, Lowey S. Preparation of myosin and its subfragments from rabbit skeletal muscle. Methods Enzymol 85: 55–71, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKillop DF, Geeves MA. Regulation of the interaction between actin and myosin subfragment 1: evidence for three states of the thin filament. Biophys J 65: 693–701, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Metzger JM, Fitts RH. Role of intracellular pH in muscle fatigue. J Appl Physiol 62: 1392–1397, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Metzger JM, Parmacek MS, Barr E, Pasyk K, Lin WI, Cochrane KL, Field LJ, Leiden JM. Skeletal troponin C reduces contractile sensitivity to acidosis in cardiac myocytes from transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 9036–9040, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morimoto S, Harada K, Ohtsuki I. Roles of troponin isoforms in pH dependence of contraction in rabbit fast and slow skeletal and cardiac muscles. J Biochem 126: 121–129, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moss RL. Effects on shortening velocity of rabbit skeletal muscle due to variations in the level of thin-filament activation. J Physiol 377: 487–505, 1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nyitrai M, Rossi R, Adamek N, Pellegrino MA, Bottinelli R, Geeves MA. What limits the velocity of fast-skeletal muscle contraction in mammals? J Mol Biol 355: 432–442, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palmer S, Kentish JC. The role of troponin C in modulating the Ca2+ sensitivity of mammalian skinned cardiac and skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol 480: 45–60, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pardee JD, Spudich JA. Purification of muscle actin. Methods Enzymol 85: 164–181, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parsons B, Szczesna D, Zhao J, Van SG, Kerrick WG, Putkey JA, Potter JD. The effect of pH on the Ca2+ affinity of the Ca2+ regulatory sites of skeletal and cardiac troponin C in skinned muscle fibres. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 18: 599–609, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pate E, Cooke R. Addition of phosphate to active muscle fibers probes actomyosin states within the powerstroke. Pflügers Arch 414: 73–81, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patton C, Thompson S, Epel D. Some precautions in using chelators to buffer metals in biological solutions. Cell Calcium 35: 427–431, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perry SV. Vertebrate tropomyosin: distribution, properties and function. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 22: 5–49, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Regnier M, Homsher E. The effect of ATP analogs on posthydrolytic and force development steps in skinned skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys J 74: 3059–3071, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Regnier M, Lee DM, Homsher E. ATP analogs and muscle contraction: mechanics and kinetics of nucleoside triphosphate binding and hydrolysis. Biophys J 74: 3044–3058, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robinson P, Lipscomb S, Preston LC, Altin E, Watkins H, Ashley CC, Redwood CS. Mutations in fast skeletal troponin I, troponin T, and β-tropomyosin that cause distal arthrogryposis all increase contractile function. FASEB J 21: 896–905, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sata M, Sugiura S, Yamashita H, Fujita H, Momomura S, Serizawa T. MCI-154 increases Ca2+ sensitivity of reconstituted thin filament. A study using a novel in vitro motility assay technique. Circ Res 76: 626–633, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sata M, Yamashita H, Sugiura S, Fujita H, Momomura S, Serizawa T. A new in vitro motility assay technique to evaluate calcium sensitivity of the cardiac contractile proteins. Pflügers Arch 429: 443–445, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Siemankowski RF, Wiseman MO, White HD. ADP dissociation from actomyosin subfragment 1 is sufficiently slow to limit the unloaded shortening velocity in vertebrate muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82: 658–662, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sleep JA, Hutton RL. Exchange between inorganic phosphate and adenosine 5'-triphosphate in the medium by actomyosin subfragment 1. Biochemistry 19: 1276–1283, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Soman J, Tao T, Phillips GN., Jr Conformational variation of calcium-bound troponin C. Proteins 37: 510–511, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Swartz DR, Moss RL. Influence of a strong-binding myosin analogue on calcium-sensitive mechanical properties of skinned skeletal muscle fibers. J Biol Chem 267: 20497–20506, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Swartz DR, Yang Z, Sen A, Tikunova SB, Davis JP. Myofibrillar troponin exists in three states and there is signal transduction along skeletal myofibrillar thin filaments. J Mol Biol 361: 420–435, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Takagi Y, Shuman H, Goldman YE. Coupling between phosphate release and force generation in muscle actomyosin. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 359: 1913–1920, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takeda S, Yamashita A, Maeda K, Maeda Y. Structure of the core domain of human cardiac troponin in the Ca(2+)-saturated form. Nature 424: 35–41, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tikunova SB, Rall JA, Davis JP. Effect of hydrophobic residue substitutions with glutamine on Ca(2+) binding and exchange with the N-domain of troponin C. Biochemistry 41: 6697–6705, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tyska MJ, Warshaw DM. The myosin power stroke. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 51: 1–15, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Urboniene D, Dias FA, Pena JR, Walker LA, Solaro RJ, Wolska BM. Expression of slow skeletal troponin I in adult mouse heart helps to maintain the left ventricular systolic function during respiratory hypercapnia. Circ Res 97: 70–77, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.VanBuren P, Alix SL, Gorga JA, Begin KJ, LeWinter MM, Alpert NR. Cardiac troponin T isoforms demonstrate similar effects on mechanical performance in a regulated contractile system. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H1665–H1671, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.VanBuren P, Guilford WH, Kennedy G, Wu J, Warshaw DM. Smooth muscle myosin: a high force-generating molecular motor. Biophys J 68: 256S-258S, 1995 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.VanBuren P, Palmiter KA, Warshaw DM. Tropomyosin directly modulates actomyosin mechanical performance at the level of a single actin filament. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 12488–12493, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.VanBuren P, Work SS, Warshaw DM. Enhanced force generation by smooth muscle myosin in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 202–205, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vinogradova MV, Stone DB, Malanina GG, Karatzaferi C, Cooke R, Mendelson RA, Fletterick RJ. Ca(2+)-regulated structural changes in troponin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 5038–5043, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Webb MR, Hibberd MG, Goldman YE, Trentham DR. Oxygen exchange between Pi in the medium and water during ATP hydrolysis mediated by skinned fibers from rabbit skeletal muscle. Evidence for Pi binding to a force-generating state. J Biol Chem 261: 15557–15564, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weiss S, Rossi R, Pellegrino MA, Bottinelli R, Geeves MA. Differing ADP release rates from myosin heavy chain isoforms define the shortening velocity of skeletal muscle fibers. J Biol Chem 276: 45902–45908, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]