Abstract

Background:

While there are many opinions about the expected knee function, sports participation, and risk of knee reinjury following nonsurgical treatment of injuries of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), there is a lack of knowledge about the clinical course following nonsurgical treatment compared with that after surgical treatment.

Methods:

This prospective cohort study included 143 patients with an ACL injury. Isokinetic knee extension and flexion strength and patient-reported knee function as recorded on the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) 2000 form were collected at baseline, six weeks, and two years. Sports participation was reported monthly for two years with use of an online activity survey. Knee reinjuries were reported at the follow-up evaluations and in a monthly online survey. Repeated analysis of variance (ANOVA), generalized estimating equation (GEE) models, and Cox regression analysis were used to analyze group differences in functional outcomes, sports participation, and knee reinjuries, respectively.

Results:

The surgically treated patients (n = 100) were significantly younger, more likely to participate in level-I sports, and less likely to participate in level-II sports prior to injury than the nonsurgically treated patients (n = 43). There were no significant group-by-time effects on functional outcome. The crude analysis showed that surgically treated patients were more likely to sustain a knee reinjury and to participate in level-I sports in the second year of the follow-up period. After propensity score adjustment, these differences were nonsignificant; however, the nonsurgically treated patients were significantly more likely to participate in level-II sports during the first year of the follow-up period and in level-III sports over the two years. After two years, 30% of all patients had an extensor strength deficit, 31% had a flexor strength deficit, 20% had patient-reported knee function below the normal range, and 20% had experienced knee reinjury.

Conclusions:

There were few differences between the clinical courses following nonsurgical and surgical treatment of ACL injury in this prospective cohort study. Regardless of treatment course, a considerable number of patients did not fully recover following the ACL injury, and future work should focus on improving the outcomes for these patients.

Level of Evidence:

Therapeutic Level II. See Instructions for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Injuries to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) are common in sports, and they may lead to reduced knee function and sports participation as well as the early onset of knee osteoarthritis1. A wish to return to pivoting sports remains the most important indication for ACL reconstruction, and it has been argued that surgery improves the ability to return to sports as well as reduces the risk of knee reinjury2-4. However, there is a lack of evidence that the outcomes of surgical treatment are better than those of nonsurgical treatment with respect to knee function, sports participation, or the early onset of knee osteoarthritis5-8.

Nonsurgical and surgical treatment courses differ not only with regard to whether or not patients undergo ACL reconstruction but also with regard to rehabilitation and recommendations for future sports participation7. Clinicians often must counsel patients for whom either surgical or nonsurgical treatment is a reasonable alternative. In order to guide treatment decisions, knowledge about the clinical course following both treatment options is important. Studies on the outcomes after treatment as it is practiced provide knowledge on the expected outcomes in different patient groups, and a prospective design enables documentation of why patients choose the treatment that they choose. However, nonsurgically and surgically treated patient populations may differ in age and preinjury activity level9,10, two factors that also affect outcome11,12. While there have been several previous observational studies of outcomes following nonsurgical and surgical treatment of a torn ACL10,13-17, the presence of both measured and unmeasured differences between patient groups makes it difficult to conclude whether the outcome is caused by the treatment or by preexisting differences between patient groups. Although seldom utilized, statistical balancing of measured confounders reduces this bias.

The aim of this prospective cohort study was to evaluate knee function, sports participation, and knee reinjuries over two years in a group of patients who chose either nonsurgical or surgical treatment for an ACL injury. To provide information on how the outcome was affected by known baseline differences between the patient groups, we report both unadjusted and adjusted estimates.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

During the years 2007 to 2011, 143 consecutive patients were included in this prospective cohort study (Fig. 1). All patients were recruited from the Norwegian Sports Medicine Clinic (NIMI) and had sustained an ACL rupture within the previous three months. The diagnosis was confirmed with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and a side-to-side difference of ≥3 mm measured with a KT-1000 arthrometer (MEDmetric, San Diego, California). Other inclusion criteria were an age of thirteen to sixty years and participation in level-I or II sports18 twice a week or more (Table I). Patients were excluded if they had a current or previous injury to the contralateral leg or if the MRI showed another grade-III ligament injury, fracture, or full-thickness articular cartilage damage. Patients with a meniscal tear were excluded only if they had pain or effusion during or following plyometric activities.

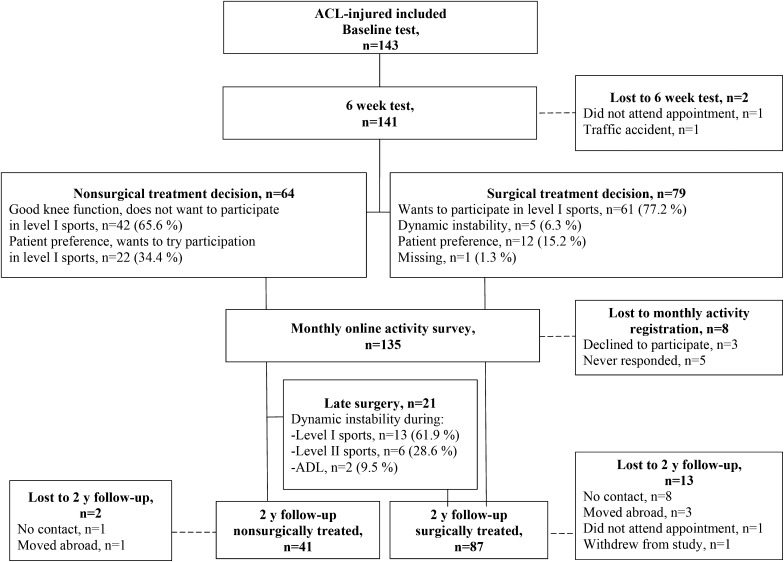

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient participation in the study. ADL = activities of daily living. One nonsurgically treated and four surgically treated patients did not perform strength testing at the two-year follow-up evaluation because of recently sustained injuries.

TABLE I.

Sports Recorded in the Monthly Online Activity Survey Classified According to Activity Level

| Sport | Activity Level |

| Handball, soccer, basketball, floorball | I |

| Volleyball, martial arts, gymnastics, ice hockey, tennis/squash, alpine/telemark skiing, snowboarding, dancing/aerobics | II |

| Cross-country skiing, running, cycling, swimming, strength training | III |

All patients signed an informed-consent form prior to inclusion in the study. The study was approved by the regional ethical committee for South-Eastern Norway. The study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02115451).

Treatment Algorithm

Before inclusion, the patients underwent rehabilitation to resolve initial impairments. Immediately after inclusion, all underwent five weeks of rehabilitation following the protocol that we described previously19. During these weeks, patients received information about nonsurgical and surgical treatment. After this period, they chose the type of treatment and the main reason for their choice was recorded prospectively. Nonsurgically treated patients underwent continued rehabilitation as needed, typically for two to three additional months. Surgically treated patients underwent ACL reconstruction with bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft, single-bundle hamstring autograft, or double-bundle hamstring autograft. The postoperative rehabilitation consisted mainly of strength training, neuromuscular training, and plyometrics and lasted for six to twelve months18.

All patients were advised not to return to level-I or II sports (Table I) until the limb symmetry indexes were ≥90% for hamstring and quadriceps strength as well as for four hop tests7. In addition, surgically treated patients were recommended to avoid level-II sports for the first six postoperative months and level-I sports for the first nine postoperative months. Nonsurgically treated patients were advised not to participate in any level-I sports forever.

Data Collection

Testing was performed at baseline, after completion of the five-week rehabilitation program (six-week test), and two years later (nonsurgically treated patients) or two years postoperatively (surgically treated patients). After the patient performed a standardized warm-up on a stationary bicycle, the isokinetic concentric muscle strength of the knee extensors and knee flexors was measured at 60°/sec with a Biodex 6000 dynamometer (Biodex Medical Systems, Shirley, New York). Four trial repetitions were performed with submaximal effort, followed by a one-minute rest, and then five test repetitions were recorded. The uninjured leg was always tested first. For assessment of patient-reported knee function, the patients completed the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) 2000 form, which is a valid, reliable, and responsive measure of knee function in patients with knee injuries20,21.

An online survey (QuestBack version 9.6; QuestBack AS, Oslo, Norway) was used to record monthly sports participation in the period between the six-week test and the two-year follow-up for nonsurgically treated patients, and between the surgery and the two-year follow-up for surgically treated patients22. The online activity survey posed the question: “Which of the following sports have you participated in during the last four weeks?” followed by the sports listed in Table I. Patients were also asked how many times they had, on average, participated in those sports. This response was categorized as zero or once per week, two or three times per week, four or five times per week, or more than five times per week. The online activity survey is highly reliable and provides a valid representation of sports participation in this patient group22.

Patients reported whether or not they had experienced reinjury in the index or contralateral knee at the follow-up evaluations and on the monthly online survey. Patients who reported knee reinjury underwent clinical examination by a physical therapist or orthopaedic surgeon. According to the standard practice at our institution, the diagnosis was verified with use of MRI and/or during surgery when clinically indicated.

Data Management and Statistical Analysis

Muscle strength was reported as the limb symmetry index for peak torque: (peak torque of involved leg)/(peak torque of uninvolved leg) × 100. The number of patients with a limb symmetry index of <90% and an IKDC-2000 score below the age and sex-specific 15th percentile for uninjured individuals11 was also reported. Participation in level-I, II, and III sports was defined as participation in at least one sport at the respective level.

Group differences in nominal variables were analyzed with the chi-square or Fisher exact test. Independent t tests were used to analyze differences in normally distributed continuous variables, and the Mann-Whitney U test was utilized when variables were not normally distributed.

Knee-function change over time and group differences in the change over time were analyzed with a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). The a priori sample-size estimation showed that thirty-three patients were needed in each group to detect a small group-by-time effect on the IKDC-2000 scores (Cohen’s f = 0.2, between-measures correlation = 0.6). The standardized response mean from baseline to the two-year follow-up evaluation was reported for all functional outcomes, and was calculated on the basis of the mean change from baseline to the two-year follow-up evaluation divided by the standard deviation (SD) of the change23. Standardized response mean values of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 were regarded as small, moderate, and large changes, respectively24.

To analyze group differences in level-I, II, and III sports participation and in weekly frequency of sports participation, generalized estimating equation (GEE) models were fitted, with adjustment for dependence between months with a first-order autoregressive correlation structure. The logit link and binomial variance functions were used for participation in level-I, II and III sports, whereas the identity link and Gaussian variance functions were used in the analysis of frequency of sports participation. Robust standard error estimates were used in all analyses. The analyses of participation in level-I and II sports were stratified by the first and second year of the follow-up period because of significant group-by-time interactions.

Cox regression analysis with robust estimation of standard errors was used to assess group differences in the risk of knee reinjury. Significance was tested with the Wald test.

To account for potentially important baseline differences between surgically and nonsurgically treated patients, propensity score covariate-adjusted analyses were performed for all outcomes. The propensity score was estimated with use of logic regression and provides a single metric of a patient’s probability of being surgically treated, based on the following independent variables: preinjury participation in level-I sports, preinjury participation in level-II sports, age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and concomitant injuries as reported in Table II. The analysis of reinjuries was not adjusted for postinjury sports participation because postinjury sports participation is likely to be affected by treatment. The mean propensity scores (and SD) of the nonsurgically and surgically treated patients were 0.54 ± 0.26 and 0.77 ± 0.16, respectively, with an area under the curve of 0.76 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.67 to 0.85). Sensitivity analyses were performed by comparing results from the full data set with results after trimming non-overlapping regions of the propensity score (87.5% of the data retained). Findings were consistent and led to similar conclusions.

TABLE II.

Descriptive Characteristics of Nonsurgically and Surgically Treated Patients

| Nonsurgical (N = 43) | Surgical (N = 100) | P Value | |

| Preinjury participation (yes/no [% yes]) | |||

| Level I | 19/24 (44) | 80/20 (80) | <0.001 |

| Level II | 30/13 (70) | 51/49 (51) | 0.038 |

| Sex (F/M [% F]) | 24/19 (56) | 56/44 (56) | 0.984 |

| Age* (yr) | 30.2 ± 8.8 | 24.0 ± 7.2 | <0.001 |

| Height* (cm) | 175.6 ± 8.9 | 173.8 ± 9.0 | 0.278 |

| Weight* (kg) | 72.7 ± 11.7 | 72.6 ± 14.5 | 0.974 |

| BMI* (kg/m2) | 23.5 ± 2.6 | 23.9 ± 3.3 | 0.479 |

| Concomitant injuries† (no. [%]) | |||

| Medial meniscus | 10 (23) | 25 (25) | 0.842 |

| Lateral meniscus | 6 (14) | 22 (22) | 0.266 |

| Medial cartilage | 3 (7) | 3 (3) | 0.365 |

| Lateral cartilage | 4 (9.3) | 10 (10) | 1.000 |

| Medial collateral ligament (grades I-II) | 12 (27.9) | 28 (28) | 0.991 |

| Lateral collateral ligament (grades I-II) | 4 (9) | 1 (1) | 0.029 |

| Popliteus | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 1.000 |

| No concomitant meniscal, cartilage, ligament, or muscle injury | 18 (42) | 44 (44) | 0.813 |

| Time from injury to baseline test* (mo) | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 0.615 |

| Time from injury to 6-week test* (mo) | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 0.695 |

The values are given as the mean and standard deviation.

Diagnosed with MRI at inclusion.

Source of Funding

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01HD37985 and R37HD37985.

Results

Of the 143 included patients, forty-three (30%) remained nonsurgically treated and 100 (70%) underwent ACL reconstruction (Fig. 1). Seventy-nine patients made a primary decision to undergo ACL reconstruction, and twenty-one decided later to undergo surgery after initially opting for nonsurgical treatment. Descriptive characteristics and outcomes for these two groups of patients (primary and later decision) can be found in the Appendix.

The nonsurgically treated group was significantly older than the surgically treated group (p < 0.001), less likely to participate in level-I sports prior to injury (p < 0.001), and more likely to participate in level-II sports prior to injury (p = 0.038) (Table II). The two-year follow-up was performed 24.5 ± 0.7 months after the six-week test for nonsurgically treated patients and 24.4 ± 0.6 months after surgery for the surgically treated patients (p = 0.493).

At the time of ACL reconstruction, thirty-two patients (32%) had concomitant surgery on one meniscus (twenty-eight patients) or both menisci (four patients). The medial meniscus was repaired in fifteen patients (15%) and partially resected in five (5%). The lateral meniscus was repaired in one patient (1%) and partially resected in fifteen (15%). No surgical procedures related to the index injury were performed in the nonsurgically treated group.

Knee Function

There were no significant group differences in baseline IKDC-2000 scores or knee extension and flexion strength (all p ≥ 0.16), and no significant group-by-time effects were found (Table III). Both groups showed large standardized response mean values for the IKDC-2000 scores and moderate-to-large standardized response mean values for extension and flexion strength of the involved leg. At the two-year follow-up evaluation, seven nonsurgically treated patients (17%) and nineteen surgically treated patients (22%) had IKDC-2000 scores below the normative 15th percentile. Nine nonsurgically treated patients (23%) and twenty-eight surgically treated patients (34%) had a knee-extension limb symmetry index of <90%, and nine nonsurgically treated patients (23%) and twenty-nine surgically treated patients (35%) had a knee-flexion limb symmetry index of <90%.

TABLE III.

Functional Outcomes of Nonsurgically and Surgically Treated Patients from Baseline to the Two-Year Follow-up Evaluation

| Baseline* |

6 Wk* |

2 Yr* |

Standardized Response Mean from Baseline to 2 Yr |

P Value |

|||||||

| Nonsurgical | Surgical | Nonsurgical | Surgical | Nonsurgical | Surgical | Time P Value | Nonsurgical | Surgical | Group × Time | Propensity-Score-Adjusted Group × Time | |

| IKDC-2000 score | 72.8 ± 11.3 | 69.8 ± 11.5 | 80.4 ± 10.4 | 77.8 ± 11.2 | 89.2 ± 11.3 | 88.9 ± 12.1 | <0.001 | 1.06 | 1.21 | 0.650 | 0.261 |

| Knee extension strength | |||||||||||

| Uninvolved (Nm) | 186.8 ± 46.3 | 193.6 ± 52.3 | 195.1 ± 49.6 | 204.4 ± 52.5 | 198.4 ± 55.4 | 213.1 ± 55.3 | <0.001 | 0.49 | 0.59 | 0.472 | 0.788 |

| Involved (Nm) | 167.1 ± 43.0 | 171.7 ± 48.1 | 180.8 ± 45.4 | 190.0 ± 49.3 | 190.3 ± 51.1 | 200.9 ± 55.5 | <0.001 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.676 | 0.906 |

| Limb symmetry (%) | 90.0 ± 10.9 | 89.0 ± 10.5 | 93.2 ± 8.0 | 93.5 ± 10.6 | 96.4 ± 9.8 | 99.2 ± 15.2 | <0.001 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.664 | 0.448 |

| Knee flexion strength | |||||||||||

| Uninvolved (Nm) | 95.4 ± 29.1 | 95.9 ± 26.1 | 101.2 ± 29.1 | 104.4 ± 26.3 | 104.5 ± 31.9 | 108.6 ± 29.2 | <0.001 | 0.55 | 0.73 | 0.408 | 0.638 |

| Involved (Nm) | 88.8 ± 26.2 | 91.3 ± 25.8 | 98.3 ± 26.8 | 101.8 ± 26.9 | 102.6 ± 29.0 | 102.6 ± 29.3 | <0.001 | 0.80 | 0.60 | 0.413 | 0.689 |

| Limb symmetry (%) | 94.9 ± 15.2 | 95.7 ± 12.4 | 97.9 ± 10.8 | 97.7 ± 10.6 | 99.2 ± 15.2 | 94.7 ± 11.5 | 0.257 | 0.21 | −0.08 | 0.165 | 0.924 |

The values are given as the mean and standard deviation and represent the patients for whom data were available at the time of follow-up. IKDC-2000 scores were available for forty-one nonsurgically treated patients and eighty-six surgically treated patients (one patient did not return for the six-week assessment). Knee extension and flexion strength data were available for forty nonsurgically treated patients and eighty-one surgically treated patients (two patients did not return for the six-week assessment).

Sports Participation

The overall response rate for the online activity survey was 87%. In total, 2820 observations from 135 patients were included in the analyses. The follow-up period was from the six-week test to the two-year follow-up evaluation for the nonsurgically treated patients and from the surgery to the two-year follow-up evaluation for the surgically treated patients.

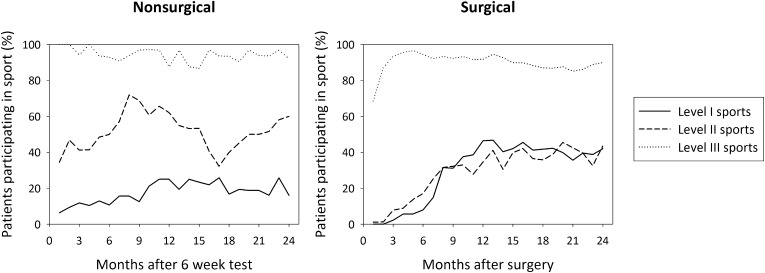

Consistent with the differences in preinjury sports participation, nonsurgically and surgically treated patients had different sports-activity profiles after the injury (Fig. 2). The crude (unadjusted) analysis showed that a significantly higher number of surgically treated patients participated in level-I sports in the second year of the follow-up period (p = 0.004); however, there was no significant difference after propensity-score adjustment (Table IV). The adjusted analyses showed that a significantly higher number of nonsurgically treated patients participated in level-III sports over the two years (p = 0.034) and in level-II sports in the first year of the follow-up period (p < 0.001). In every month of the two-year follow-up period, the median frequency of sports participation was two to three times per week in both groups, and it did not differ significantly between the groups (adjusted β [95% CI]: 0.20 [−0.01 to 0.41], p = 0.060).

Fig. 2.

Percentages of nonsurgically (n = 37) and surgically treated (n = 98) patients participating in level-I, II, and III sports over two years (unadjusted data representing all patients, regardless of preinjury participation in respective level of sport).

TABLE IV.

Comparison of Monthly Sports Participation Between Nonsurgically and Surgically Treated Patients Over Two Postoperative Years*

| Crude Odds Ratio† (95% CI), P Value | Propensity-Score-Adjusted Odds Ratio† (95% CI), P Value | |

| Participation in level-I sports | ||

| 1st year of follow-up | 1.45 (0.76-2.76), 0.265 | 0.73 (0.38-1.41), 0.350 |

| 2nd year of follow-up | 2.78 (1.40-5.52), 0.004 | 1.30 (0.61-2.78), 0.497 |

| Participation in level-II sports | ||

| 1st year of follow-up | 0.23 (0.14-0.38), <0.001 | 0.28 (0.16-0.49), <0.001 |

| 2nd year of follow-up | 0.65 (0.37-1.14), 0.131 | 0.88 (0.47-1.34), 0.689 |

| Participation in level-III sports | 0.47 (0.21-1.05), 0.065 | 0.41 (0.18-0.94), 0.034 |

Sports participation was recorded from the six-week test to the two-year test in the nonsurgical group and from the ACL reconstruction to the two-year test in the surgical group.

An odds ratio of >1 indicates a higher number of patients treated with ACL reconstruction participating in sports.

Knee Reinjuries

Four nonsurgically treated patients (9%) reported a total of seven knee reinjuries (Table V). Twenty-four surgically treated patients (24%) reported a total of thirty-four knee reinjuries in the period from the surgery to the two-year follow-up evaluation. Nonsurgically treated patients sustained 8.0 (95% CI: 2.1 to 13.9) knee reinjuries per 100 patient-years in the period from the six-week test to the two-year follow-up evaluation, and the surgically treated patients sustained 16.8 (95% CI: 11.1 to 22.4) reinjuries per 100 patient-years in the period from the surgery to the two-year follow-up evaluation. While surgically treated patients had a significantly higher crude risk of knee reinjury (hazard ratio [95% CI]: 2.89 [1.02 to 8.13], p = 0.045), there was no significant difference between the groups after propensity-score adjustment (adjusted hazard ratio [95% CI]: 1.87 [0.52 to 6.78], p = 0.340).

TABLE V.

Knee Reinjuries in Nonsurgically and Surgically Treated Patients*

| Nonsurgical (N = 43) | Surgical (N = 100) | |

| Index knee (no. [%]) | ||

| ACL rerupture | 0 | 8 (8) |

| Medial meniscus | 2 (5) | 9 (9) |

| Lateral meniscus | 2 (5) | 4 (4) |

| Medial cartilage | 1 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Lateral cartilage | 1 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Patellofemoral cartilage | 3 (3) | |

| Medial collateral ligament | 1 (1) | |

| Patellar subluxation | 1 (1) | |

| Contralateral knee (no. [%]) | ||

| ACL rupture | 1 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Lateral meniscus | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Medial collateral ligament | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

Knee reinjuries were recorded from the six-week test to the two-year test in the nonsurgical group and from the ACL reconstruction to the two-year test in the surgical group. Of the forty-one injuries, five (12%) were exclusively diagnosed clinically; fifteen (37%) were diagnosed by clinical examination and MRI; thirteen (32%) were diagnosed by clinical examination and arthroscopy; and eight (20%) were diagnosed by clinical examination, MRI, and arthroscopy. The seven injuries in the nonsurgical group were all diagnosed by clinical examination and arthroscopy.

Discussion

Knowledge of the clinical courses following nonsurgical and surgical treatment of ACL injuries is needed to provide patients with evidence-based recommendations for treatment. Our prospective cohort study suggests that there are few differences in the clinical course between patients who choose nonsurgical treatment and those who choose surgical treatment. However, surgically treated patients were more active in level-I sports in the second postoperative year and had a higher crude risk of knee reinjury. These findings were not significant in the adjusted analyses, suggesting that the higher participation in level-I sports and reinjury risk were attributed to surgically treated patients being younger and more active in level-I sports prior to injury rather than to the treatment course. After propensity-score adjustment, the only significant differences found were that nonsurgically treated patients were more likely to participate in level-II sports in the first year of the follow-up period and in level-III sports over two years. The first finding can be explained by surgically treated patients having reduced knee function and activity restrictions early after ACL reconstruction, and the difference in level-III sports participation was likely not important as >85% of the surgically treated patients also participated in these sports from the second to the twenty-fourth postoperative month (Fig. 2).

No significant differences were detected over time in patient-reported knee function or muscle strength between our nonsurgically and surgically treated patients. These results are in line with the findings in previous studies by Frobell et al.5,6, Ageberg et al.25, Daniel et al.13, Meuffels et al.8, and Myklebust et al.16. Consequently, current evidence does not suggest that patients who choose nonsurgical treatment should expect inferior knee function compared with those who choose ACL reconstruction. However, it is likely that some patients will benefit from surgery while others will not. Although previous studies have provided evidence of a differential response to ACL injury26,27, there is no evidence-based algorithm that accurately identifies nonsurgically treated patients who will be able to participate in level-I sports over the long-term28. For this reason, all of our patients were advised to undergo ACL reconstruction if they intended to participate in level-I sports. Still, 34% of the patients who chose a nonsurgical approach intended to resume level-I sports when they made the treatment choice (Fig. 1). As shown previously7, there was a large degree of noncompliance with the recommended activity restrictions (Fig. 2). Thirty-four percent of the surgically treated patients participated in level-I sports and 18% participated in level-II sports earlier than recommended, while 56% of the nonsurgically treated patients at some point participated in level-I sports despite the recommendations to avoid them.

In terms of graft choice and meniscal procedures performed at the time of ACL reconstruction, the surgically treated patients in this study were similar to patients included in the Scandinavian ACL registries29. Although we did not find significant differences in surgical procedures performed at the time of ACL reconstruction between patients who underwent ACL reconstruction as a primary intervention and those who did so as a result of a later decision (see Appendix), studies with larger samples have shown that the prevalence of meniscal tears increases with a longer time from the injury to the ACL reconstruction30,31. However, the comparison period for sports participation and reinjury risk was from the surgery to two years postoperatively, regardless of the timing of the surgery. The four injuries that occurred between the ACL injury and the surgery in the surgically treated group (see Appendix) therefore did not increase the reported reinjury rate in surgically treated patients.

As the current study was not powered to assess differences between patients who made a primary decision and those who made a late decision to undergo ACL reconstruction, the inferences that can be drawn from these results are limited. Patients who made a late decision to undergo ACL reconstruction did so because of episodes of dynamic instability, mainly during level-I-sports activity (Fig. 1). After surgery, a significantly lower number of these patients participated in level-I sports compared with those who chose surgery as a primary decision, and only two patients who made a late decision to undergo surgery reported knee reinjuries. Fear of reinjury is a more frequent reason for ceasing sports participation than knee problems32. As there were no significant differences in functional outcomes, it is plausible to suggest that the patients in our study who made a late decision to undergo surgery avoided level-I sports to protect their knees from additional injury rather than because of a decreased ability to participate in sports.

While this study provides information on the clinical course following treatment of ACL injuries, the observational design prohibits solid conclusions about differences in treatment efficacy. Although we provided propensity-score-adjusted results to reduce the inherent selection bias of the design, unmeasured confounding factors were not accounted for and the patient sample was too small for stratification. Our results may not apply to patients who undergo other surgical or rehabilitation interventions, or to institutions with different criteria for treatment selection. A knee reinjury was recorded only if the patient reported one. Thus, future studies including follow-up MRIs of all patients are needed to evaluate the total extent of structural changes in these patient groups. Additionally, we did not assess the relationship between postinjury sports participation and knee reinjuries in this study; it should be an area of focus in future studies. Although the average functional outcome of both treatments was good, one-fifth of all patients experienced knee reinjury and one-third of patients who initially chose nonsurgical treatment later underwent ACL reconstruction. Studies examining patients characteristics that can predict the success and failure of both treatments are therefore needed. Finally, continued follow-up is necessary to evaluate longer-term sports participation, reinjury risk, and development of knee osteoarthritis.

In conclusion, this prospective cohort study suggests that there are few differences in the two-year clinical course between patients who choose nonsurgical treatment of an ACL injury and those who choose surgical treatment. While surgically treated patients had a significantly higher crude risk of knee reinjury, there was no significant difference in the risk after propensity-score adjustment. Patients in both groups showed large improvements in patient-reported knee function; however, at two years, one-fifth of the patients reported knee reinjuries and one-third exhibited muscle strength deficits.

Appendix

Tables showing descriptive patients characteristics, surgical data, functional outcomes, monthly sports participation, and knee reinjuries according to whether the decision to undergo ACL reconstruction was primary or late are available with the online version of this article as a data supplement at jbjs.org.

Acknowledgments

Note: The authors thank physical therapists Håvard Moksnes, Annika Storevold, Ida Svege, Espen Selboskar, Karin Rydevik, and Marte Lund for assistance with the data collection in this study and Ingar Holme for statistical advice. They also acknowledge the Norwegian Sports Medicine Clinic (NIMI) for supporting the Norwegian Research Center for Active Rehabilitation (NAR; www.active-rehab.no) with rehabilitation facilities and research staff.

Footnotes

Investigation performed at the Norwegian Research Center for Active Rehabilitation, Department of Sports Medicine, Norwegian School of Sport Sciences, and the Department of Orthopaedics, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway

A commentary by Donald C. Fithian, MD, is linked to the online version of this article at jbjs.org.

Disclosure: One or more of the authors received payments or services, either directly or indirectly (i.e., via his or her institution), from a third party in support of an aspect of this work. None of the authors, or their institution(s), have had any financial relationship, in the thirty-six months prior to submission of this work, with any entity in the biomedical arena that could be perceived to influence or have the potential to influence what is written in this work. In addition, no author has had any other relationships, or has engaged in any other activities, that could be perceived to influence or have the potential to influence what is written in this work. The complete Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest submitted by authors are always provided with the online version of the article.

References

- 1.Beynnon BD, Johnson RJ, Abate JA, Fleming BC, Nichols CE. Treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injuries, part I. Am J Sports Med. 2005October;33(10):1579-602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beaufils P, Hulet C, Dhénain M, Nizard R, Nourissat G, Pujol N. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of meniscal lesions and isolated lesions of the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee in adults. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009October;95(6):437-42 Epub 2009 Sep 10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meuffels DE, Poldervaart MT, Diercks RL, Fievez AW, Patt TW, Hart CP, Hammacher ER, Meer Fv, Goedhart EA, Lenssen AF, Muller-Ploeger SB, Pols MA, Saris DB. Guideline on anterior cruciate ligament injury. Acta Orthop. 2012August;83(4):379-86 Epub 2012 Aug 20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roos H, Karlsson J. Anterior cruciate ligament instability and reconstruction. Review of current trends in treatment. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1998December;8(6):426-31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frobell RB, Roos EM, Roos HP, Ranstam J, Lohmander LS. A randomized trial of treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tears. N Engl J Med. 2010July22;363(4):331-42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frobell RB, Roos HP, Roos EM, Roemer FW, Ranstam J, Lohmander LS. Treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tear: five year outcome of randomised trial. BMJ. 2013January24;346:f232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grindem H, Eitzen I, Moksnes H, Snyder-Mackler L, Risberg MA. A pair-matched comparison of return to pivoting sports at 1 year in anterior cruciate ligament-injured patients after a nonoperative versus an operative treatment course. Am J Sports Med. 2012November;40(11):2509-16 Epub 2012 Sep 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meuffels DE, Favejee MM, Vissers MM, Heijboer MP, Reijman M, Verhaar JA. Ten year follow-up study comparing conservative versus operative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament ruptures. A matched-pair analysis of high level athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2009May;43(5):347-51 Epub 2008 Jul 4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eitzen I, Moksnes H, Snyder-Mackler L, Engebretsen L, Risberg MA. Functional tests should be accentuated more in the decision for ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010November;18(11):1517-25 Epub 2010 Apr 22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fithian DC, Paxton EW, Stone ML, Luetzow WF, Csintalan RP, Phelan D, Daniel DM. Prospective trial of a treatment algorithm for the management of the anterior cruciate ligament-injured knee. Am J Sports Med. 2005March;33(3):335-46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson AF, Irrgang JJ, Kocher MS, Mann BJ, Harrast JJ; International Knee Documentation Committee. The International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Evaluation Form: normative data. Am J Sports Med. 2006January;34(1):128-35 Epub 2005 Oct 11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salmon L, Russell V, Musgrove T, Pinczewski L, Refshauge K. Incidence and risk factors for graft rupture and contralateral rupture after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2005August;21(8):948-57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daniel DM, Stone ML, Dobson BE, Fithian DC, Rossman DJ, Kaufman KR. Fate of the ACL-injured patient. A prospective outcome study. Am J Sports Med. 1994Sep-Oct;22(5):632-44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fink C, Hoser C, Hackl W, Navarro RA, Benedetto KP. Long-term outcome of operative or nonoperative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament rupture—is sports activity a determining variable? Int J Sports Med. 2001May;22(4):304-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moksnes H, Risberg MA. Performance-based functional evaluation of non-operative and operative treatment after anterior cruciate ligament injury. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2009June;19(3):345-55 Epub 2009 May 28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myklebust G, Holm I, Maehlum S, Engebretsen L, Bahr R. Clinical, functional, and radiologic outcome in team handball players 6 to 11 years after anterior cruciate ligament injury: a follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. 2003Nov-Dec;31(6):981-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swirtun LR, Renström P. Factors affecting outcome after anterior cruciate ligament injury: a prospective study with a six-year follow-up. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2008June;18(3):318-24 Epub 2007 Dec 7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hefti F, Müller W, Jakob RP, Stäubli HU. Evaluation of knee ligament injuries with the IKDC form. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1993;1(3-4):226-34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eitzen I, Moksnes H, Snyder-Mackler L, Risberg MA. A progressive 5-week exercise therapy program leads to significant improvement in knee function early after anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010November;40(11):705-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irrgang JJ, Anderson AF, Boland AL, Harner CD, Kurosaka M, Neyret P, Richmond JC, Shelborne KD. Development and validation of the International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form. Am J Sports Med. 2001Sep-Oct;29(5):600-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irrgang JJ, Anderson AF, Boland AL, Harner CD, Neyret P, Richmond JC, Shelbourne KD; International Knee Documentation Committee. Responsiveness of the International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form. Am J Sports Med. 2006October;34(10):1567-73 Epub 2006 Jul 26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grindem H, Eitzen I, Snyder-Mackler L, Risberg MA. Online registration of monthly sports participation after anterior cruciate ligament injury: a reliability and validity study. Br J Sports Med. 2013May3 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stratford PW, Binkley JM, Riddle DL. Health status measures: strategies and analytic methods for assessing change scores. Phys Ther. 1996October;76(10):1109-23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Husted JA, Cook RJ, Farewell VT, Gladman DD. Methods for assessing responsiveness: a critical review and recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000May;53(5):459-68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ageberg E, Thomeé R, Neeter C, Silbernagel KG, Roos EM. Muscle strength and functional performance in patients with anterior cruciate ligament injury treated with training and surgical reconstruction or training only: a two to five-year followup. Arthritis Rheum. 2008December15;59(12):1773-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fitzgerald GK, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. A decision-making scheme for returning patients to high-level activity with nonoperative treatment after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8(2):76-82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurd WJ, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. A 10-year prospective trial of a patient management algorithm and screening examination for highly active individuals with anterior cruciate ligament injury: Part 1, outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2008January;36(1):40-7 Epub 2007 Oct 16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moksnes H, Snyder-Mackler L, Risberg MA. Individuals with an anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee classified as noncopers may be candidates for nonsurgical rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008October;38(10):586-95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Granan LP, Forssblad M, Lind M, Engebretsen L. The Scandinavian ACL registries 2004-2007: baseline epidemiology. Acta Orthop. 2009October;80(5):563-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Church S, Keating JF. Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: timing of surgery and the incidence of meniscal tears and degenerative change. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005December;87(12):1639-42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Granan LP, Bahr R, Lie SA, Engebretsen L. Timing of anterior cruciate ligament reconstructive surgery and risk of cartilage lesions and meniscal tears: a cohort study based on the Norwegian National Knee Ligament Registry. Am J Sports Med. 2009May;37(5):955-61 Epub 2009 Feb 26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ardern CL, Webster KE, Taylor NF, Feller JA. Return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the state of play. Br J Sports Med. 2011June;45(7):596-606 Epub 2011 Mar 11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]