Abstract

Since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, there has been considerable speculation about how many employers will stop offering health insurance once the major coverage provisions of the Act take effect. While some observers predict little aggregate effect, others believe that 2014 marks the beginning of the end for our current system of employer- sponsored insurance. We address the question “how will employer health insurance offering respond to health reform?” using theoretical and empirical evidence. First, we describe economic models of why employers offer insurance. Second, we recap the relevant provisions of health reform and use our economic framework to consider how they may affect employer offers. Third, we review the various predictions that have been made on this subject. Finally, we offer some observations on interpreting early data from 2014.

“If you like the plan you have, you can keep it.

” President Obama

Since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, there has been considerable speculation about how many employers will stop offering health insurance to their workers once the major coverage provisions of the Act health insurance exchanges, premium tax credits for low-income families, individual and employer mandates, and a Medicaid expansion take effect. Speculation has only increased since the recent announcement by the Department of the Treasury that the implementation of the employer penalty for not offering insurance will be delayed until 2015.

The response of employers to health reform is important for several reasons. First, less employer coverage may increase Federal outlays if more workers receive premium tax credits in the exchanges or enroll in Medicaid. Second, if the employers who drop coverage have relatively less healthy workers, this worsens the exchange risk pool, driving up average premiums. Finally, the Affordable Care Act was presented to the American public as a reform that would not seriously disrupt existing employer-sponsored coverage. To the approximately 160 million Americans who have such coverage and are for the most part quite satisfied with it, large-scale employer dropping of coverage would be an unwelcome surprise.

Some observers predict that health reform will have relatively little aggregate effect on employer-sponsored coverage. Others believe that 2014 marks the beginning of the end for our current system of employer-sponsored health insurance. This disagreement is driven at least in part by fundamental differences in assumptions about employer behavior. To put it more simply, what you think about how health reform will affect employer-sponsored coverage depends on why you think employers provide insurance in the first place. We will soon have early data on employers’ health insurance offerings for 2014. Making sense of these data determining whether it is business as usual or the beginning of the end requires an underlying model of how employers respond to incentives in choosing a menu of employee benefits.

In this essay, we address the question “how will employer health insurance offering respond to health reform?” from multiple perspectives. First, we briefly describe economic models of why employers offer insurance and how they might respond to the changes that health reform brings. Second, we recap the relevant provisions of health reform and use our economic framework to consider how they are likely to affect employer offers. Third, we review the various predictions that have been made on this subject. Finally, we offer some observations on what to look for as early data from 2014 begin to come in.

1. The Economics of Employer Health Insurance Offering

Employers currently face no requirement to provide health insurance and yet most do; nearly 80% of full-time workers are eligible for employer-sponsored coverage (1). The economic explanation for this relies on three factors: employers have a comparative advantage in providing health insurance; workers bear the cost of health insurance through lower wages; and employer benefit offerings reflect, albeit imperfectly, worker demand for health insurance.

Employers have a comparative advantage in providing health insurance

There are three reasons why employer-sponsored insurance tends to be a better deal than coverage in the individual market. First, employer-sponsored health insurance premiums are not subject to federal or state income taxes or the Social Security payroll tax. For a typical worker in the 15 percent tax bracket, the tax exclusion reduces the cost of insurance by roughly one-third (2). For higher income workers, the subsidy is even greater. Research has shown that this tax subsidy increases the likelihood that small firms offer insurance and leads employers of all sizes to provide more generous coverage (3, 4). Second, employer provision of insurance mitigates adverse selection. Workers in a large firm constitute an effective risk pool, with premiums from the healthy subsidizing expenditures on the sick, and aggregate medical claims that are fairly predictable from one year to the next. In contrast, adverse selection in the individual market greatly limits the availability of coverage. Third, since administrative and marketing costs are relatively fixed, employers enjoy significant economies of scale. For a large group, the “loading factor” per enrollee - which includes profits and any risk premium in addition to administrative and marketing costs - may be as little as half what it would be for individually purchased insurance (5).

Workers bear the cost of health insurance through lower wages

Economists are in near-unanimous agreement that workers ultimately pay for health insurance through lower wages (6–8), unless minimum wages are a binding constraint (9). The logic is that employers care about the cost of total compensation, not how compensation is split between wages and benefits and, therefore, will only offer insurance if wages adjust to keep total compensation constant. Because of the cost advantages just described, workers who want health insurance will find this trade-off to be a good deal, particularly if the marginal tax rate on earned income is high. There is considerable empirical evidence of a compensating wage differential for health insurance (10–13).

Employer benefit offerings take into account worker preferences

Not all workers want health insurance, in the sense that they are not willing to trade off the amount of wages required to pay for it. Even among workers who want insurance, some will want more generous coverage than others. Because of both practical considerations and Federal non-discrimination rules, employers generally cannot tailor health benefits to the preferences of each individual worker (14, 15). Rather, they must balance the preferences of workers who have a strong demand for insurance against those who are less willing to trade wages for benefits, although it is not entirely clear how they do this (16–18). Firms may also tailor employee premium contribution requirements or the scope of benefits in response to diversity in worker demand for insurance (19). Clearly, the problem is simpler for employers with workers who are similar to one another in their demand for insurance, although firms may need to hire diverse workers depending on the nature of their business.

The advantages afforded to employer-sponsored insurance explain why most Americans receive their health coverage through the workplace. Nonetheless, as increases in health care costs have outpaced wage and price inflation, employer-sponsored coverage has declined (20).

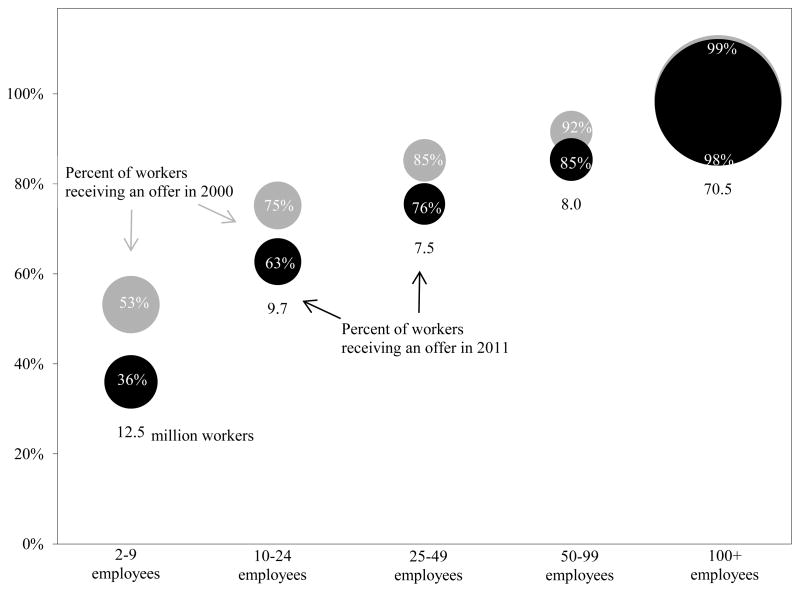

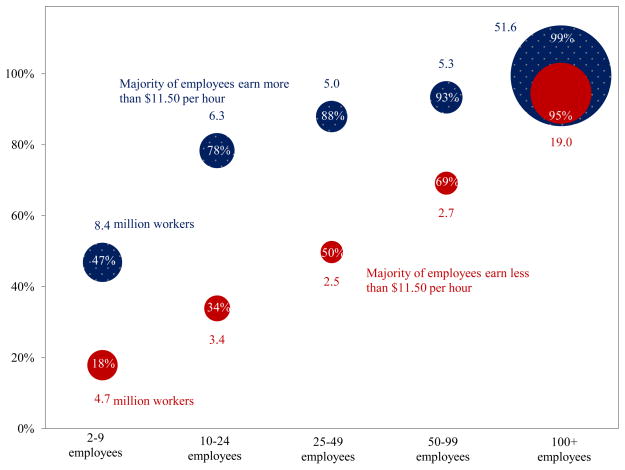

Exhibits 1 and 2 illustrate three features of the current market landscape that are important for understanding the potential impact of the Affordable Care Act on employer-sponsored coverage. First, the size of the circles highlights a fundamental feature of the labor market: while most firms are very small roughly 60 percent of all private-sector employers have fewer than 10 employees nearly two-thirds of private sector workers are employed at firms with more than 100 employees. This means that the aggregate effect of the Affordable Care Act on employer-sponsored insurance will depend disproportionately on the decisions made by large employers and their workers.

Exhibit 1.

Percent of Private Sector Workers Receiving Offers of Health Insurance, by Firm Size, 2000 and 2011

Source: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, Insurance Component.

Exhibit 2.

Percent of Private Sector Workers Receiving Offers of Health Insurance, by Firm Size and Majority Low-Wage Status, 2011

Source: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, Insurance Component.

Second, because both administrative economies of scale and the benefits of risk pooling increase with group size, there is a strong positive relationship between firm size and insurance offers. Only 36 percent of workers in firms with fewer than 10 employees are offered coverage, compared to over 96 percent of workers in firms with 50 or more employees. Part of this difference is likely due to the fact that small employers do not enjoy the economies of scale and risk pooling that large employers do; in these respects, the market for small group coverage is characterized by some of the same problems as the market for individual coverage. The data in Exhibit 1 also show that while employer-based insurance rates have been stable for large firms, small business offer rates have fallen.

Third, Exhibit 2 shows that holding constant firm size, there is a strong relationship between employee wages and employer-sponsored insurance coverage. The red circles correspond to employers in which the majority of workers are “low-wage” workers, defined here as workers earning less than $11.50 per hour. The dotted blue circles represent employers where the majority of workers earn more than this amount. For all but the largest size category, workers at high-wage firms are substantially more likely to be offered coverage than those working at low-wage firms. The relationship between wages and employer-sponsored insurance is in part driven by the tax exclusion for employer premiums, which presents greater tax savings to higher-income workers. Other work has documented the regressive nature of this tax expenditure (21).

2. Relevant Provisions of the Affordable Care Act

With these facts in mind, we consider which provisions of the Affordable Care Act are likely to affect employers’ decisions about whether or not to offer insurance. First, though, we note that there are other dimensions on which employers may respond to these provisions. They may change employee premium contribution requirements; they may adjust plan generosity; they may offer more or fewer plans; they may change their policies for which workers are eligible for coverage. We do not attempt to consider these infra-marginal decisions here, focusing instead on the bottom line offer/not offer decision, which has been the focus of most policy attention.

Exhibit 3 describes the provisions of the ACA that are most relevant to employer health insurance offering. We group these provisions into two categories: those that affect employer decisions about offering health insurance coverage directly, and those that affect this decision indirectly, through their effect on worker demand for coverage from their employers. Provisions with direct effects include employer penalties for not offering affordable coverage, small business health insurance exchanges, and small business health insurance tax credits. Provisions that affect employers indirectly through their effect on workers’ demand include health insurance exchanges, premium tax credits, Medicaid expansion, and the individual mandate. While we do not attempt to predict the impact that all of these provisions will have on employer offering this would, in effect, replicate the work of the microsimulation models discussed in the next section some general observations come from the simple economic understanding of firm behavior that is outlined above.

Exhibit 3.

Major Affordable Care Act Provisions Affecting Employer Health Insurance Offering

| Provisions affecting employers directly: | Impact on offering: |

|---|---|

| Employer penalties: Employers with 50 or more full-time workers face a penalty if any of their full-time workers qualifies for a premium tax credit. If the firm does not offer coverage at all the penalty is $2,000 for each full-time worker beyond the first 30. If the firm offers coverage that is not affordable, the penalty is the lesser of (1) $3,000 for each full-time worker who receives a credit or (2) $2,000 for each full-time worker in the firm beyond the first 30. Originally scheduled to take effect in 2014, HHS recently announced that this penalty will not be implemented until 2015. | Increase offering for large firms |

| Small business exchanges: Establishes the Small Business Health Options Program (“SHOP exchange”) on which small employers, defined as those with fewer than 50 full-time workers, can get coverage. Between 2014 and 2016, states may choose to allow employers with 50 to 100 workers in the SHOP exchange; in 2017 and later, they may choose to allow employers of any size to offer coverage from the SHOP exchange. As of 2014 in some states and 2015 in others, a small employer may designate a menu of insurance options for employees. | Increase offering for small firms |

| Small business tax credits: Employers with fewer than 25 employees and average annual wages below $50,000 are eligible for premium tax credits to offset the cost of coverage for up to 2 years. The maximum credit is currently 35 percent, rising to 50 percent in 2014. In 2014 and later, coverage must be purchased through a SHOP exchange. | Increase offering for small, low-wage firms |

| Provisions affecting worker demand for employer-sponsored insurance: | |

| Health insurance exchanges with community rating and guaranteed issue: Exchanges should, in theory, provide a viable alternative to employer-sponsored insurance since they capture the “economies of scale” and “risk pooling” advantages that employers have. In practice this depends on what the exchange risk pool looks like. | Reduce offering for firms with many low- income workers |

| Premium tax credits: Premium tax credits are available to workers without access to affordable employer-sponsored coverage, where “affordable” means that the worker’s share of the premium for single coverage does not exceed 9.5 of the worker’s income. | Reduce offering for firms with many low- income workers |

| Medicaid expansion: In some states, all individuals with incomes below 138% of the Federal poverty threshold will become eligible for Medicaid. | Reduce offering for firms with many low- income workers |

| Individual mandate: Individuals who lack coverage for more than 3 months in a year face a penalty that is phased in between 2014 and 2016. The penalty is the greater of $285/1% of family income in 2014, $975/2% of family income in 2015, and $2,085/2.5% of family income in 2016 and later. Exemptions apply in the case of hardship, families with incomes below the tax filing threshold, Indians, and certain religious groups. | Increase offering |

We begin by noting that the provisions affecting employers directly some of which affect only large firms (50 or more full time employees) and some of which affect only small firms all increase the likelihood that firms will offer coverage. Consider, first, the effect of the employer “responsibility requirement” facing large employers who do not offer affordable coverage to their full-time workers. As already noted, nearly all firms large enough to face this penalty already offer coverage. The small minority of large firms that do not currently offer insurance will face a choice of either offering coverage (and presumably reducing cash wages) or paying the penalty. For a typical full-time employee (40 hours per week, 50 weeks per year) a $2,000 penalty raises the employer’s cost by $1/hour (although the per-employee cost is reduced by the fact that the penalty does not apply to an employer’s first thirty employees). Some employers in this group may decide that it is now worth offering insurance. Others will not and will simply pay the penalty. Others will find ways to appear to be “small” employers in order to avoid the penalty, such as reducing hours below the ACA definition of “full time” (30 hours) or converting employees to contractors. For small employers, who face no penalty for not offering coverage, the cost of offering coverage is reduced by both the small business tax credits and the Small Business Health Options Program (“SHOP exchanges”), insurance marketplaces intended to give small employers the administrative efficiencies and risk-pooling long enjoyed by large employers.

Offsetting these incentives for employers to offer insurance is the fact that with one exception (the individual mandate), the indirect provisions listed in Exhibit 3 largely decrease worker demand for employer coverage. They do this by creating viable alternatives to employer-sponsored coverage that cost low-income workers less than employer coverage. The net effect of these new alternatives on employers’ incentive to offer coverage depends on the characteristics of the firm and its workforce (22). In particular, for low-income workers, the benefit of exchange coverage subsidized by premium tax credits exceeds the value of the tax exclusion associated with employer-sponsored coverage, while for higher-income workers the opposite will be true. Blumberg et al. identify 250% of the Federal Poverty Level as the threshold at which the value of this credit will (on average) exceed the value of the tax exclusion for employer-sponsored insurance (23), although the calculation will depend on household circumstances, employee contributions, and plan parameters. Since subsidized exchange coverage is available only for lower-income workers without access to affordable employer-sponsored coverage, some lower-income workers who wanted employer coverage in the past will now prefer not to be offered it, since it stands between them and a generous tax credit. For employers who are already balancing the varied demands of different workers in deciding whether or not to offer coverage this may tip the balance against offering coverage. Or it may not.

Back on the other side of the ledger (i.e. in favor of employers continuing to offer insurance), the individual mandate should increase workers’ demand for employer-sponsored coverage. Indeed, the fact that employer offering actually increased after reform was implemented in Massachusetts has largely been credited to the fact that workers want to avoid paying tax penalties (24–27). This “crowd-in” effect for some workers potentially offsets the reduction in demand for employer-sponsored coverage among others.

3. Projections of How the Affordable Care Act Will Affect Employer Offers

These competing incentives make it difficult to make simple predictions of how employers and employees will respond. It is particularly hard to predict how small employers will respond to the new incentives under the ACA. On the one hand, the factors just described reduce small employers’ cost of offering coverage relative to what it is now; on the other hand, they do not face penalties for not offering coverage, and to the extent that their workers can now obtain affordable coverage through the exchanges, they do not necessarily need to offer coverage in order to attract workers. As noted above, however, the decisions of large employers will drive the aggregate impact of the ACA on offering of employer-sponsored insurance.

In light of this theoretical uncertainty, two main approaches have been used to make projections about how the number of Americans with employer-sponsored insurance will change after all provisions of the Affordable Care Act are in place. The most widely cited estimates, including that of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) who calculate legislation’s budgetary “score”, are based on a microsimulation methodology (28, 29). The second approach is to ask employers directly about how, if at all, their decisions concerning health insurance are likely to change in 2014 and beyond. We review both types of predictions.

Microsimulations

Microsimulation models combine data from nationally representative surveys with the best evidence from the research literature to predict how families, employers and insurers will respond to policies that alter their incentives (30, 31). The models used to simulate the effects of health reform are based on the conventional economic theory summarized above, although details vary across models. Employers are assumed to set their compensation policies to attract and retain the desired number and type of employees, who implicitly pay for employer-sponsored insurance with reduced wages. Employer and employee behavior is modeled within the context of key institutional features of the system, such as Federal non-discrimination rules that essentially prohibit firms from offering benefits to some full-time workers but not others. Insurance premiums, which are a key input to these decisions, are assumed to depend on the expected medical costs of the individuals who are insured and on market regulations, such as guaranteed issue and community rating.

In addition to CBO, organizations that have conducted microsimulation analyses include the Urban Institute (32, 33), the RAND Corporation (34), the Lewin Group (35), and the Office of the Actuary (OACT) of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (36). The bottom-line predictions from these analyses about how health reform will affect employer offering are summarized in Exhibit 4. Given the number of assumptions that must be made and the complexity of the models, it is not surprising that different models yield different results. However, it is clear from Exhibit 4 that even with different assumptions, the various models tell a similar story. Consistent with economic logic discussed above, the models predict that the Affordable Care Act will cause little change in the number of Americans covered by employer-sponsored health insurance. The predicted change in employer-sponsored coverage ranges from the CBO’s estimate of a 1.8 percentage point decline to RAND’s estimate of a 2.9 percentage point increase. These estimated changes represent the net effect of some workers and their dependents gaining coverage and others moving from employer coverage to other categories.

Exhibit 4.

Simulated Impacts of Health Insurance Coverage for Nonelderly Americans

| Rate in 2011 | Estimated ACA Impact in Percentage Points | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBO/JCT | RAND | Urban | Lewin | OACT | ||

|

|

|

|||||

| Employer Coverage

|

||||||

| Traditional Market | 58.3% | NA | −10.1 | −7.9 | −4.7 | NA |

| SHOP | 0.0% | NA | 13.0 | 7.7 | 3.7 | NA |

| Total | 58.3% | −1.8 | 2.9 | −0.2 | −1.0 | −0.5 |

| Individual Coverage

|

||||||

| Traditional Market | 7.1% | −1.1 | −6.1 | −4.3 | −2.8 | −5.6 |

| Exchange | 0.0% | 8.4 | 11.9 | 8.6 | 10.0 | 11.3 |

| Total | 7.1% | 7.3 | 5.8 | 4.3 | 7.1 | 5.7 |

| Medicaid/CHIP | 17.6% | 5.8 | 4.3 | 6.2 | 4.9 | 7.3 |

| Other | 6.9% | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Uninsured | 17.9% | −11.3 | −12.3 | −10.4 | −10.9 | −11.7 |

Notes: Each microsimulation compares the Affordable Care Act to continuation of the status quo. However, the studies simulate the Act’s effect in different years; we report estimates for 2019 for CBO/JCT and OACT, who present estimates for several years. Different assumptions govern how quickly the Act’s effects are realized and how coverage trends in the status quo. While all microsimulations include the major market reforms and coverage incentives of the Affordable Care Act, they differ somewhat in their inclusion of smaller provisions, such as the extension of parents’ policies to adult children 25 and younger. Although the Congressional Budget Office (38) and the Urban Institute (39, 45) have issued new estimates reflecting updated policies, we use older CBO and Urban estimates that are more comparable to the policy assumptions used by RAND, Lewin, and OACT. Lewin and OACT simulate insurance coverage for the full population including elderly, but we attribute all changes to the nonelderly population. “Other” includes Medicare and military-related insurance. The changes by type of coverage do not add up to reduction in uninsured because some individuals will have more than one type of coverage.

These modest effects stand in contrast to a prediction by the American Action Forum (AAF) that 43 million workers will lose access to employer coverage (37). We believe that a critical assumption driving this difference is that while most microsimulation models assume that in deciding whether or not to offer coverage employers aggregate their workers’ demand for health insurance as described above, the AAF estimates appear to assume employers offer insurance to those who want it and withhold it from those who do not. This could happen only if employers ignore federal non-discrimination regulations or dramatically restructure firms so that workers with low demand for employer-based insurance are isolated in separate firms or in part-time/temporary jobs. In addition, the AAF estimates overstate the number of workers below 250 percent of the poverty line currently enrolled in employer coverage and fail to include any offsetting increases in employer coverage due to factors such as the individual mandate.

Because there is substantial uncertainty associated with projecting the effects of any policy, especially one this significant, modelers typically conduct sensitivity analyses, varying key behavioral assumptions. For example, in a 2012 report, the CBO discusses how alternative assumptions about employers’ responsiveness to employee utility and their willingness to restructure their firms affect their results (29). The most important finding that emerges from this sensitivity testing is that even when alternative assumptions yield divergent estimates of the number of workers with employer-sponsored insurance, they produce similar estimates of overall insurance coverage and of the Federal budgetary cost of the coverage provisions. The main reason for this latter result is that greater exchange enrollment entails greater spending on premium tax credits, but lower tax expenditures for premiums as well as increased revenue from employer penalties.

The estimates summarized in Exhibit 4 pertain to the Affordable Care Act as enacted in March 2010. Recent developments such as states declining to expand Medicaid eligibility and the one-year delay in the enforcement of the employer mandate are not reflected, since most researchers have not released updated estimates. As of this writing, only CBO has released updated estimates to reflect the fact that not all states will expand Medicaid; CBO assumed that 30 percent of those otherwise eligible for Medicaid would reside in states that do not fully expand eligibility and would instead enroll in the exchanges or go uninsured (38). The Urban Institute predicts that the delay in the employer mandate will have no effects on rates of coverage (39). These findings reinforce our view that rates of employer-sponsored coverage are driven by the business case for benefits for the firm’s workers.

Predictions Based on Employer Surveys

Two caveats apply to interpreting survey evidence on firm behavior. Firstly, because most firms are small but most employees work for large firms, estimates of the number of firms adding or dropping coverage can be difficult to translate into corresponding numbers of individuals affected. Secondly, surveys of employers currently offering insurance the sampling frame of the surveys described below will miss offsetting increases from firms beginning to offer benefits, and therefore cannot predict net changes in coverage.

With those caveats noted, the results of a number of surveys are consistent with the predictions from microsimulation models. Most surveys suggest that most employers offering health insurance now will continue to offer it in 2014, and that the vast majority of individuals enrolled in employer-sponsored insurance will continue in it next year. In one 2012 survey, 9% of currently offering large firms, representing 3% of the workforce, said that they anticipated dropping coverage in the next three years, an estimate consistent with the microsimulation estimates of gross flows from employer-based coverage (40). In a 2013 survey, nearly all (98%) of very large firms (firms with more than 1000 employees, which account for about half of total employment) said that they expected health benefits to be an important component of compensation three to five years from now (41).

These survey results suggest that reports of the demise of employer-sponsored coverage soon after the Act’s passage (42) may have reflected a lack of awareness of its true effects on employers’ incentives. The International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans has surveyed plans repeatedly since the Affordable Care Act became law (43, 44). Over the last two years, it reports that fewer employers are “taking a ‘wait-and-see’ approach” and more employers have “modeled the financial impact of reform”. Over the same period, the number of employers who are considering dropping benefits has fallen by half to 2% and the share of employers reporting they will definitely offer coverage in 2014 jumped from 46% to 69%.

At the same time, employers continue to report uncertainty about various provisions of the Affordable Care Act. In March 2013, 84% of employers reported that they were still studying the Act (44). Only two-thirds of large employers are “familiar” with the shared responsibility penalty (40). As firms see the Act’s provisions in action, they may explore new health insurance options. Among firms with 50 to 100 employees, 71% reported that they would be more likely to participate in the SHOP exchanges if a large choice of plans were available at the employer’s targeted benefit level (40).

4. Summing up and looking ahead

For an employer, deciding whether or not to offer health insurance already requires a complex calculus that takes into account a host of factors including employee preferences, wages, taxes, and regulations. The Affordable Care Act throws more into the mix new taxes, new subsidies, new requirements, new insurance markets. But it does not fundamentally change the economics of the firm. Microsimulation models built on sound economic principles have for the most part predicted relatively small declines in employer-sponsored coverage as a result of the Affordable Care Act, and we believe that these predictions are likely to be correct.

If we are wrong, though, how will we know? Inevitably, reports will come in that some employers are dropping coverage. Although it will be tempting to attribute reported changes to the Affordable Care Act, it is important to interpret new data on employer-sponsored insurance coverage within the context of the basic economics of firm behavior and pre-existing trends. For decades, the combination of rising health care costs and stagnant earnings for middle income workers have led to a gradual, but steady decline in employer-sponsored insurance. This trend is the appropriate baseline against which to measure the impact of health reform.

It is, perhaps, stating the obvious to add a caution against reading too much into anecdotal reports. But, for reasons described above, even surveys with large samples can produce results that are difficult to interpret. Fortunately, there are several high quality data resources that will be useful for monitoring changes in employer-sponsored insurance and drawing inferences about the effect of health reform. We expect that the earliest data on rates of coverage will come in September 2014, when both the National Health Interview Survey and the Current Population Survey should report on individuals’ sources of coverage in early 2014. If historical patterns hold, the Kaiser Family Foundation’s survey of employer-sponsored insurance will be published the same month. A year later, in September 2015 the American Community Survey will provide state and metro-area estimates of individual-level coverage patterns, and in July 2015 the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey will provide further information on employer offerings. Of course, effects in early 2014 will not be the last word as individuals and employers may take a wait-and-see approach. And since the employer penalty for not offering coverage will not take effect until 2015, it may be several years before the true effects of these policies become evident.

These data will begin to answer the question posed in our title. Given the historical importance of employer-sponsored insurance, the attention that is paid to this question is understandable. However, it is not a question of great economic significance. There is no efficiency argument for preferring private insurance facilitated by employers to private insurance facilitated by the state or any other mechanism that could be used to pool risk and achieve administrative economies of scale. It is also important to remember that relying on firms as a mechanism for pooling insurance risk generates efficiency costs because of labor market distortions. A better functioning individual health insurance market has the potential to improve labor market efficiency by reducing job-lock, eliminating a barrier to entrepreneurship and making it easier for workers to find a job and an insurance plan that matches their preferences. If the shift from employer-sponsored insurance to individual coverage is greater than projected, these labor market gains may be significant.

Contributor Information

Thomas Buchmueller, Ross School of Business, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Colleen Carey, School of Public Health, University of Michigan.

Helen G. Levy, Institute for Social Research and the Ford School of Public Policy, University of Michigan

References

- 1.Fronstin P. Employment-Based Health Benefits: Trends in Access and Coverage, 1997–2010. Employee Benefit Research Institute; 2012. p. 370. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gruber J. The Tax Exclusion for Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance. National Tax Journal. 2011;64(2):511–30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gruber J, Lettau M. How Elastic Is the Firm’s Demand for Health Insurance? Journal of Public Economics. 2004;88(7–8):1273–93. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Royalty AB. Tax Preferences for Fringe Benefits and Workers’ Eligibility for Employer Health Insurance. Journal of Public Economics. 2000;75(2):209–27. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swartz K. Reinsuring Health: Why More Middle-Class People Are Uninsured and What Government Can Do. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cawley J, Morrisey M, Simon K. The Results of the 2012 Survey of Health Economists; San Diego, CA. ASHEcon Luncheon at the Allied Social Sciences Association Convention; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuchs VR. Economics, Values, and Health Care Reform. American Economic Review. 1996;86(1):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrisey MA, Cawley J. Health Economists’ Views of Health Policy. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2008;33(4):707–24. doi: 10.1215/03616878-2008-013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baicker K, Levy H. Employer Health Insurance Mandates and the Risk of Unemployment. Risk Management and Insurance Review. 2008;11(1):109–39. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baicker K, Chandra A. The Consequences of the Growth of Health Insurance Premiums. American Economic Review. 2005;95(2):214–8. doi: 10.1257/000282805774670121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gruber J. The incidence of mandated maternity benefits. The American Economic Review. 1994;84(3):622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolstad JT, Kowalski AE. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 17933. 2012. Mandate-Based Health Reform and the Labor Market: Evidence from the Massachusetts Reform. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olson CA. Do workers accepts lower wages in exchanges for health benefits? Journal of Labor Economics. 2002;20(2):S91–S114. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrington WJ, McCue K, Pierce B. Nondiscrimination Rules and the Distribution of Fringe Benefits. Journal of Labor Economics. 2002;20(2):S5–33. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dafny L, Ho K, Varela M. Let Them Have Choice: Gains from Shifting Away from Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance and toward an Individual Exchange. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 2013;5(1):32–58. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bundorf MK. Employee Demand for Health Insurance and Employer Health Plan Choices. Journal of Health Economics. 2002;21(1):65–88. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein GS, Pauly MV. Group Health Insurance as a Local Public Good. In: Rosett R, editor. The Role of Health Insurance in the Health Services Sector. New York: Watson Academic; 1976. pp. 73–114. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monheit AC, Vistnes JP. Health insurance availability at the workplace - How important are worker preferences? J Hum Resour. 1999;34(4):770–85. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller NH. Pricing health benefits: A cost-minimization approach. J Health Econ. 2005;24(5):931–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilmer TP, Kronick RG. Hard times and health insurance: how many Americans will be uninsured by 2010? Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(4):w573–7. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selden TM, Gray BM. Tax subsidies for employment-related health insurance: estimates for 2006. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25(6):1568–79. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.6.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abraham JM, Graven P, Feldman R. Employer-Sponsored Insurance and Health Reform: Doing the Math. Washington, DC: National Institute for Health Care Reform; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blumberg LJ, Buettgens M, Feder J, Holahan J. Why Employers Will Continue to Provide Health Insurance: The Impact of the Affordable Care Act. Washington, DC: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Urban Institute; 2011. Oct, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gabel JR, Whitmore H, Pickreign J, Sellheim W, Shova KC, Bassett V. After The Mandates: Massachusetts Employers Continue To Support Health Reform As More Firms Offer Coverage. Health Affairs. 2008:W566–W75. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.6.w566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gruber J. The Impacts of the Affordable Care Act: How Reasonable are the Projections? National Tax Journal. 2011;64:893–908. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Long SK, Stockley K, Dahlen H. Massachusetts Health Reforms: Uninsurance Remains Low, Self-Reported Health Status Improves As State Prepares To Tackle Costs. Health Affairs. 2012;31(2):444–51. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pricewaterhouse Coopers. The Massachusetts Experience: Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance Post Reform. Washington, DC: Health Research Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Congressional Budget Office. H.R. 4872, Reconciliation Act of 2010 (Final Health Care Legislation) Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office; 2010. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- 29.Congressional Budget Office. CBO and JCT’s Estimates of the Effects of the Affordable Care Act on the Number of People Obtaining Employment-Based Health Insurance. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office; 2012. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glied S, Remler DK, Zivin JG. Inside the sausage factory: improving estimates of the effects of health insurance expansion proposals. The Milbank quarterly. 2002;80(4):603–35. iii. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abraham JM. Using microsimulation models to inform U.S. health policy making. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(2 Pt 2):686–95. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garrett B, Buettgens M. Employer-Sponsored Insurance under Health Care Reform: Reports of Its Demise are Premature. Washington, DC: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Urban Institute; 2011. Jan, [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buettgens M, Garrett B, Holahan J. America Under the Affordable Care Act. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eibner C, Girosi F, Price CC, Cordova A, Hussey PS, Beckman A, et al. Establishing State Health Insurance Exchanges: Implications for Health Insurance Enrollment, Spending, and Small Businesses. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2010. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Lewin Group. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA): Long Term Costs for Governments, Employers, Families and Providers. Falls Church, VA: Lewin Group; 2010. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foster RS. Estimated Financial Effects of the ‘Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act,’ as Amended. Baltimore, MD: Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holtz-Eakin D, Smith C. Labor Markets and Health Care Reform: New Results. Washington, DC: American Action Forum; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Congressional Budget Office. Effects on Health Insurance and the Federal Budget for the Insurance Coverage Provisions in the Affordable Care Act May 2013 Baseline. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office; 2013. May, [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blumberg LJ, Holahan J, Buettgens M. It’s No Contest: The ACA’s Employer Mandate Has Far Less Effect on Coverage and Costs Than the Individual Mandate. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deloitte. 2012 Deloitte Survey of US Employers: Opinions about the US Health Care System and Plans for Employee Health Benefits: Deloitte Center for Health Solutions and Deloitte Consulting. 2012. Jul, [Google Scholar]

- 41.Towers Watson/NBGH. Towers Watson/NBGH Employer Survey on Purchasing Value in Health Care. 2013. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singhal S, Stueland J, Ungerman D. McKinsey Quarterly. 2011. How U.S. Health Care Reform Will Affect Employee Benefits. [Google Scholar]

- 43.International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans. Health Care Reform: 2012 Employer Actions Update: International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans. 2012. May, [Google Scholar]

- 44.International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans. 2013 Employer-Sponsored Health Care: ACA’s Impact: International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans. 2013. May, [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blumberg LJ, Buettgens M, Feder J, Holahan J. Why Employers Will Continue to Provide Health Insurance: The Impact of the Affordable Care Act. Inquiry. 2012;49(2):116–26. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_49.02.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2011. Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau and U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration; 2012. Sep, [Google Scholar]