Abstract

Background/Objectives

More than half of independent ambulatory patients with spinal cord injury (SCI) need a walking device to promote levels of independence. However, long-lasting use of a walking device may introduce negative impacts for the patients. Using a standard objective test relating to the requirement of a walking device may offer a quantitative criterion to effectively monitor levels of independence of the patients. Therefore, this study investigated (1) ability of the three functional tests, including the five times sit-to-stand test (FTSST), timed up and go test (TUGT), and 10-meter walk test (10MWT) to determine the ability of walking without a walking device, and (2) the inter-tester reliability of the tests to assess functional ability in patients with SCI.

Methods

Sixty independent ambulatory patients with SCI, who walked with and without a walking device (30 subjects/group), were assessed cross-sectionally for their functional ability using the three tests. The first 20 subjects also participated in the inter-tester reliability test.

Results

The time required to complete the FTSST <14 seconds, the TUGT < 18 seconds, and the 10MWT < 6 seconds had good-to-excellent capability to determine the ability of walking without a walking device of subjects with SCI. These tests also showed excellent inter-tester reliability.

Conclusions

Methods of clinical evaluation for walking are likely performed using qualitative observation, which makes the results difficult to compare among testers and test intervals. Findings of this study offer a quantitative target criterion or a clear level of ability that patients with SCI could possibly walk without a walking device, which would benefit monitoring process for the patients.

Keywords: Tetraplegia, Paraplegia, Walking, Assistive device, Rehabilitation, Assessment

Introduction

Approximately 80% of patients with incomplete spinal cord injury (SCI) can regain ambulatory ability after participation in a rehabilitation program. However, most of them can walk non-functionally and require a walking device.1 Nowadays, there has been a trend towards the decrease of rehabilitation for patients (from 115 days in 1974 to 36 days in 2005).2 Therefore, it is likely that the patients cannot reach an optimal level of ability at the time of discharge and increase the need of a walking device to conduct daily activities.

Walking devices are commonly prescribed in order to compensate for excessive skeletal loading, reduction of lower extremity muscle strength (LEMS), and impairment of balance control. Therefore, using a walking device can help to reduce risk of falls, allow task-specific walking practice experience, promote levels of independence, and increase community participation for the patients.1,3,4 However, long-lasting use of a walking device may introduce negative impacts for the patients, e.g. abnormal walking patterns, and puts a considerable demand onto the upper extremities and energy expenditure that results in a slow walking speed and upper limb pain.5–7 Jain et al.6 found that approximately 50% of subjects with SCI who walked with a walking device, such as crutches or cane, had shoulder pain. Brotherton et al.7 reported that subjects with SCI, who used a walker could walk at only a short distance and were least likely to be able to climb a flight of stair. Mahoney et al.8 also found that the use of a walker was associated with 2.8 times increased risk for functional decline in ability to conduct daily activities in elderly. Later, continuing use of a walking device may reduce self-confidence while moving and retard ability to withdraw from the walking device.1,3 This suggests the importance of community rehabilitation and effective monitoring methods to clearly quantify functional alteration and promote level of independence of these individuals.

Clinically, methods of evaluation can be done using either qualitative or quantitative assessments.9 Qualitative observational methods are widely applied as a clinical screening tool, but the result may be subjective and highly dependent on the experience of the assessors. Moreover, the decisions about clinically important change overtime can be difficult when time intervals between visits are long or with a change in the assessors. Quantitative measures are more easily standardized and could provide objective data, thus the results can be compared among testers and test intervals. Therefore a quantitative, valid, reliable, and responsive measure is more preferable to use as a follow-up tool to monitor functional alteration in clinical and community settings.9–12

The reduction of LEMS, balance control, and walking ability can be quantified using the five times sit-to-stand test (FTSST), the timed up and go test (TUGT), and the 10-meter walk test (10MWT), respectively.10,13,14 These tests are time-based assessments that have been proved for their validity, reliability, and responsive to assess functional ability in ambulatory patients with SCI who walked with and without a walking device.11–13,15,16 Using these tests may offer a quantitative criterion to indicate a level of functional ability that the patients can walk without a walking device. Thus, this study investigated and compared the ability of these three functional tests to determine the ability of walking without a walking device in ambulatory patients with SCI using data from cut-off scores, sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve (AUC). Furthermore, the study explored inter-tester reliability of the tools. The findings would support the use of these tools to monitor and facilitate levels of independence of these patients both in clinics and communities.

Methods

Subjects

Subjects were independent ambulatory patients with SCI from either traumatic causes or non-progressive diseases from a tertiary rehabilitation center in Thailand. From sample size calculation, using data from a pilot study, the study required 60 subjects (30 subjects walked with a walking device and the rest of them walked without a walking device). The subjects were required to possess the ability of standing up from a chair or bed independently without using hands, and of walking with or without a preferred walking device at least 50 m (functional independent measure locomotor (FIM-L) scores = 6–7)11 in order for them to complete the tests used in this study with minimal effects of confounding factors, such as levels of external assistance and fatigue that might interfere with the ability to perform the tests. The patients were excluded if they had any conditions that affected ability to execute the tests, such as pain in the musculoskeletal system (at rest or with movement) with an intensity of more than 5 out of 10 according to the visual analog scale, or deformity in the spine or joints (i.e. marked kyphosis or scoliosis, leg length discrepancy, and equinovarus or equinovalgus). Eligible subjects need to sign an informed consent document approved by the local ethics committee prior to taking part in this study.

Experimental procedures

Every subject participated in the study for two consecutive days. On the first day, subjects were interviewed and assessed for their baseline demographics and SCI characteristics including causes and severity of injury, level of the lesion, post-injury time, and baseline walking ability (the ability of walking at least 50 m continuously with or without a walking device). On the second day, subjects were tested for their functional ability using the FTSST, TUGT, and 10MWT in a random order to minimize carrying-over effects due to sequences of the tests that might occur such as fatigue and learning effects. Details of the tests are described in the following sections.

Five times sit-to-stand test

The FTSST has been proposed as a sensitive and responsive tool to assess LEMS, particularly when testing without using hands (r = 0.652–0.708).14,17,18 Subjects sat on a standard armless chair with back upright and hip flexion 90°, and placed their feet flat on the floor at 10 cm behind the knees and their arms on their sides. Then they were instructed to stand up with the hips and knees in full extension, and sit down five times at a fastest and safe speed without using the arms. Then the time required to complete the test was recorded.15,16,19,20

Timed up and go test

The TUGT has been designed to measure mobility and dynamic balance control.12 Subjects stood up from a standard armrest chair, walked with or without a preferred walking device around a traffic cone that was located 3 m away from the chair, and returned to sit down on the chair at a maximum and safe speed. Then the time required to complete the test was recorded.15,16,21,22

10-Meter walk test

The 10MWT reflects walking speed that is considered as a surrogate for the overall quality of gait and motor function.11 Subjects walked at a comfortable pace with or without a walking device along a 10 m walkway. The time was recorded over the middle 4 m of the walkway in order to minimize acceleration and deceleration effects.15,16,23,24

Subjects performed three trials/test with a period of rest as needed between the trials. Then the average findings of the three trials were used for data analyses. During the tests, subjects did not wear any shoes to minimize effects of different types of shoes on the outcomes and risk of injury. In addition, they had to wear a lightweight safety belt around their waist with a physiotherapist walking or being alongside the subjects throughout the tests in order to ensure subjects’ safety and improve accuracy of the outcomes.

Reliability test

The study investigated the inter-tester reliability of the tools in the first 20 subjects who participated in the study using 3 physiotherapists who had different clinical experience (ranged 2–5 years). Prior to participation, the assessors were trained to use the same and standard methods. Then they concurrently investigated the ability of the subjects using the FTSST, TUGT, and 10MWT in a random order. Each subject performed three trials/test with a period of sufficient rest between the trials. Then the average findings for the three trials of each assessor were used to analyze the inter-tester reliability of the tools.

Statistic analyses

The data analyses were executed using the SPSS for Windows (SPSS Statistics 17.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA, serial number: 5068054). Descriptive statistics were applied to explain baseline demographics, SCI characteristics, and findings of the study. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to primarily determine discriminative ability of the tools for subjects who walked with and without a walking device. Then the receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves were further utilized to explore an optimal cut-off score, sensitivity, specificity, and AUC for the tests to indicate the ability of walking without a walking device. The ROC curve is a graphical technique that is generated by plotting sensitivity values on the y-axis and 1-specificity values on the x-axis of all possible cut-off scores for the tests using data of all subjects.25,26 The sensitivity is a true positive rate or the probability of a positive result in subjects with the condition (walked without a walking device). On the contrary, specificity is a true negative rate or the probability of a negative result in subjects without the condition (walked with a walking device). A test that perfectly discriminates between subjects who walked with and without a walking device would yield a curve that coincides with the left and top side of the plot. In addition, a perfect test would have an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 1.0, while a completely useless test would have an AUC of 0.5. In other words, the closer the AUC is to 1, the better the overall diagnostic performance of the test, and the closer it is to 0.5, the poorer the diagnostic performance of the test.26,27

The inter-tester reliability was determined using the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs 3.3) and the standard errors of measurement (SEM) to explain agreements among the testers and amount of variation or spread in the measurement errors for the tests, respectively. The highest possible value of the SEM is zero, which infers no errors of measurement or a perfectly reliable test.28 Then, the Bland–Altman plot was also utilized to explain the degree of agreement between the two testers of each functional test. This method plots the different outcomes between the two testers on the y-axis versus the average findings of these two testers on the x-axis. Thus the closer the horizontal line of the mean differences between the two testers is to the x-axis (zero), the better the reliability of the test.29 The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Table 1 presents baseline demographics and SCI characteristics of subjects. Most of them were males at a chronic stage of injury and had an SCI from non-traumatic causes. Among those who required a walking device, 16 subjects walked with walkers, 8 subjects used crutches, 6 subjects walked with cane, and none of them required an orthosis for daily walking.

Table 1 .

Baseline demographics and SCI characteristics of subjects

| Variable | Walking with a walking device (n = 30) | Walking without a walking device (n = 30) | Reliability test (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) (years)* | 49.30 ± 14.41 | 50.60 ± 9.68 | 51.05 ± 10.59 |

| Post-injury time (mean ± SD) (months)* | 61.60 ± 92.1 | 49.40 ± 66.33 | 30.3 ± 20.39 |

| Sex (male/female) (n) | 19/11 | 23/7 | 15/5 |

| Causes (non-progressive diseases/traumatic cause) (n) | 18/12 | 16/14 | 10/10 |

| Severity of SCI (AIS C/D) (n) | 7/23 | 0/30 | 2/18 |

| Levels of injury (Tetraplegia/paraplegia) (n) | 10/20 | 13/17 | 8/12 |

*Data between subjects who walked with and without a walking device were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test with the P > 0.05.

SCI, spinal cord injury; n, number; SD, standard deviation; AIS, American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale; AIS C, incomplete. Motor function is preserved below the neurological level, and more than half of key muscles below the neurological level have a muscle grade less than 3; AIS D, incomplete. Motor function is preserved below the neurological level, and at least half of key muscles below the neurological level have a muscle grade greater than or equal to 3.

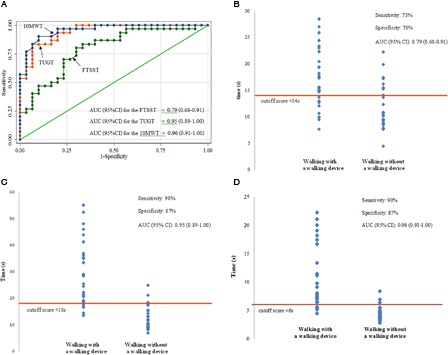

Fig. 1 demonstrates ROC curves (Fig. 1A), data distribution of subjects who walked with and without a walking device, cut-off scores, sensitivity, specificity, and AUC to discriminate the ability of walking with or without a walking device of the tests. The data demonstrated that subjects who walked without a walking device required significantly less time to complete the tests than those who walked with a walking device (P < 0.001, Table 2 and Fig. 1B–D). The data from ROC analysis indicated that the time required to complete the FTSST < 14 seconds (Fig. 1B), the TUGT < 18 seconds (Fig. 1C), and the 10MWT < 6 seconds (Fig. 1D) had good-to-excellent capability to indicate the ability of walking without a walking device. Comparing among the three tests, the 10MWT had the best discriminative ability, followed by the TUGT and the FTSST, respectively (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 .

ROC curves, data distribution, cut-off score, sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of the three functional tests. (A) Comparison of the ROC curves for the three functional tests. (B) Data for the FTSST. (C) Data for the TUGT. (D) Data for the 10MWT.

Table 2 .

Functional abilities in subjects who walked with and without a walking device

| Functional tests | Walking with a walking device (n = 30) | Walking without a walking device (n = 30) | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Five times sit-to-stand test (second) | 16.99 ± 5.50 (15.54) | 11.49 ± 4.08 (10.20) | <0.001 |

| Timed up and go test (second) | 29.09 ± 11.86 (28.17) | 12.44 ± 4.34 (11.07) | <0.001 |

| 10-meter walk test (second) | 12.10 ± 5.77 (11.44) | 4.47 ± 1.16 (4.15) | <0.001 |

Data were presented using mean ± SD (median).

*P value from the Mann–Whitney U test.

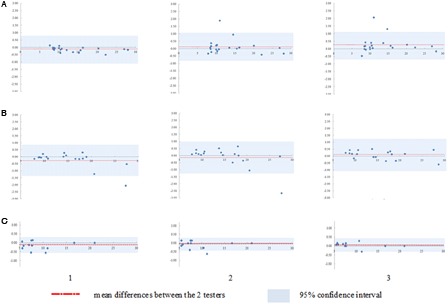

The inter-tester reliability of the tests was excellent when analyzed using the ICCs (ICCs (3.3) = 0.994–0.998, Table 3). However, the SEM data indicated that the 10MWT had the least amount of data variation, followed by the FTSST and the TUGT, respectively (Table 3). Fig. 2 shows the Bland–Altman plot for the tests. The horizontal dash lines (the mean different values between two testers) of the 10MWT were located closest to the x–axis, which indicated the best reliability test (Fig. 2).

Table 3 .

Inter-tester reliabilities of the three functional tests

| Functional tests | ICCs | 95%CI |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | SEM | ||

| Five times sit-to-stand test* | 0.998 | 0.997 | 0.999 | 0.33 |

| Timed up and go test* | 0.998 | 0.997 | 0.999 | 0.41 |

| 10-meter walk test* | 0.994 | 0.988 | 0.998 | 0.03 |

*P value from ICCs < 0.001.

CI, confidence interval; SEM, standard errors of measurements; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient.

Figure 2 .

Bland–Altman plot to assess inter-tester reliability of the three functional tools by plotting the different findings between the two testers (y-axis) against the averaged findings of the two testers (x-axis) including (1) testers A and B, (2) testers A and C, and (3) tester B and C. (A) Data for the FTSST. (B) Data for the TUGT. (C) Data for the 10MWT.

Discussion

With the decrease of rehabilitation length, it may be possible that ambulatory patients with SCI cannot achieve an optimal goal at the time of discharge and increase the need of a walking device. However, long-lasting use of a walking device may introduce negative consequences to the patients. Therefore, an effective monitoring method is crucial to clearly indicate functional alteration and promote level of independence of the patients. The findings indicated that the time required to complete the FTSST, TUGT, and 10MWT were less than 14, 18, and 6 seconds, respectively, had good-to-excellent capability to determine the ability of walking without a walking device of these individuals (Fig. 1). The findings could be used as a quantitative target criterion for functional improvement or levels of ability that the patients could wean-off a walking device. Among the three tests, the 10MWT showed the best discriminative ability, followed by the TUGT and the FTSST, respectively. These tests, particularly the 10MWT, also showed excellent inter-tester reliability (Table 3 and Fig. 2C).

Results of the 10MWT reflect walking speed that associates with motor function, walking endurance, and overall quality of gait.10 The findings of the current study suggested that subjects who walked faster than 0.67 m/second had excellent capability to walk without a walking device (sensitivity 90%, specificity 87%, AUC = 0.96). The findings associated with those of van Hedel,30 who found that the average walking speed of subjects with SCI who walked without aid was 0.70 ± 0.13 m/second (sensitivity 0.99 ± 0.02, specificity 0.94 ± 0.01, and AUC 0.99 ± 0.01). Recently, Saensook et al.16 also found that the data of the 10MWT were significantly different among ambulatory subjects with SCI, who used different types of walking devices in which those who did not required a walking device walked at a median speed of 0.86 m/second. Zorner et al.31 also reported that patients with SCI needed a walking speed at least 0.60 m/second to safely cross a street. The researchers also used this speed to categorize patients with SCI into functional and non-functional ambulators.31 Findings of the present study also indicated that the 10MWT had the best inter-tester reliability, in which the tool demonstrated the least amount of data variation (Table 3 and Fig. 2C). This may relate to characteristics of the test that incorporates less sequential tasks, thus it is easiest to be standardized and shows the least outcome variation among the testers. The findings correlated well with data of a previous study that also found excellent inter-tester reliability of the 10MWT (ICC = 0.999 for subjects with SCI who walked with a walking device, and ICC = 1.00 for those who walked without a walking device, P < 0.001).15 Since the 10MWT can easily be measured and shows excellent reliability, it has been verified for its effectiveness to predict other abilities in patients with SCI and other groups of subjects.30,32

For the TUGT, the findings suggested that subjects who required time to complete the TUGT less than 18 seconds had excellent capability to walk without a walking device (sensitivity 90%, specificity 87%, AUC = 0.95). The test required subjects to perform sequential locomotor tasks that incorporated sitting to standing, walking, and turning activities.22 Results of the test associate with levels of mobility, balance and postural control, walking ability, and risk of falls.21 Saensook et al.16 recently reported that the data of the TUGT had excellent discriminative ability for ambulatory subjects with SCI who walked with different types of a walking device (median data = 10.86, 15.80, 30.69, and 31.03 seconds for subjects who walked without a walking device, and with cane, crutches, and walker, respectively). van Hedel et al.13 reported that the TUGT had excellent and significant association with the 10MWT (r = 0.89), which may explain the similar discriminative ability of the TUGT and 10MWT. However, among the three tests, the TUGT comprised many subtasks that might be difficult to be standardized among the testers; therefore, the test showed the most data variation but still had excellent inter-tester reliability (Table 3, Fig. 2B). Currently, there are only a few evidences using TUGT in patients with SCI. The test has been applied extensively in geriatric medicine, since it has been recommended to be used as a bedside screening test for the presence of gait and balance disorder in older adults.33 However, the optimal cut-off scores to detect risk of fall remains controversial and the values reported in the literatures varied from 10 to 33 seconds.22,33,34

Ability to rise from a chair or bed independently is a crucial fundamental movement for daily activity.20 The task is mechanically demanding and requires adequate torques to be developed at each joint during spatial and temporal motion of the body segments.18 Thus, apart from muscle strength, result of the FTSST is also highly correlated with sensation, balance, speed, and psychological status of individuals.17 However, methods to perform the test incorporate the tasks with less alignment to walking ability than those of the 10MWT and TUGT. Thus the test showed lowest, but acceptable capability to determine the ability to walk without a walking device (cut-off score <14 seconds, sensitivity 73%, specificity 70%, AUC = 0.79, Fig. 1B). The findings were associated with those of Saensook et al.,16 who found that ambulatory subjects with SCI who walked without a walking device required significantly less time to complete the FTSST than those who walked with a walking device (median data = 10.58 seconds for subjects who walked without a walking device, whereas those who walked with cane, crutches, and walker used median time to complete the test ranged from 15.67 to 19.47 seconds). Previously, the FTSST has been used widely in elderly and patients with other conditions. Buatois et al.35 found that time required to complete the FTSST longer than 15 seconds indicates a high risk of recurrent fall in elderly (sensitivity 55%, specificity 65%). Mong et al.14 also reported that a cut-off score of 12 seconds could discriminate healthy elderly and subjects with stroke (sensitivity 83% and specificity 75%). From the researchers’ knowledge, there is only one study using the FTSST in ambulatory subjects with SCI. Poncumhak et al.15 reported that the FTSST had moderate correlation with FIM-L scores (rpb = −0.595), and excellent inter-tester reliability to assess functional ability in ambulatory subjects with SCI (ICCs = 0.999 for subjects with FIM-L 6 and 0.997 for subjects with FIM-L 7). Findings of this study further support the use of the FTSST in ambulatory subjects with SCI.

Findings of the study contain some limitations. First, the eligible subjects required the ability to walk independently at least 50 m in order to minimize other confounding factors that might influence the outcomes such as functional endurance and levels of external assistance. The criteria may limit the use of the findings only to the patients with relative good walking ability. Second, the study utilized a 10 m walkway and recorded the time required over 4 m in the middle of the walkway because of area limitation. Graham et al.23 reviewed 108 studies that measured walking speed in clinical research and found that the speed was mostly recorded during 4, 6, and 10 m distances. Finch et al.24 indicated that acceleration and deceleration periods of walking would take up to 3 m in order to obtain a rhythmic phase. Therefore, this study allowed 3 m before and after timing period and recorded the time over the 4 m in the middle of the 10 m walkway. Data of our previous study suggest that this method is valid and reliable to use in ambulatory subjects with SCI.15 Findings of this study also confirmed that this method had excellent inter-tester reliability. Third, the applicability of the tests may need to consider the availability of area and equipment. The 10MWT had the best discriminative ability and reliability. However, it requires a rather wide area of test (a 10 m walkway) and a stop watch. The TUGT had slightly less discriminative ability and higher SEM data, and required more equipment but it could be executed in smaller area (3 m). The FTSST had acceptable discriminative ability, and required the smallest area to execute the test. However, the results can be applied in individuals who are able to stand up without using hands. Therapists need to take these factors into account when utilizing the tests. Moreover, the gait speed for the 10MWT was recorded for a comfortable speed. van Hedel et al.36 indicated that comfortable walking speed might only partially reflect the potential to participate in the community. The ability to voluntarily increase walking speed may better reflect the remaining capacity for a community challenge.36 Thus, a further study explores a cut-off score for the fastest walking speed may offer another useful criterion to indicate the ability of walking without a walking device in these patients. Finally, the findings of this study offered a target criterion for the ability of walking without a walking device without the consideration of fall risk for the subjects.

Conclusion

The study explored capability of the FTSST, TUGT, and 10MWT to determine the ability of ambulatory subjects with SCI to walk without a walking device. The data indicated that the time required to complete the FTSST<14 seconds, the TUGT<18 seconds, and the 10MWT<6 seconds (or >0.67 m/second) can be used as a target quantitative criterion for functional gain in order for patients with SCI to walk without a walking device both during in-patient rehabilitation and after discharge. However, the application of the tests may need to consider availability of the area and equipment, and ability of the patients.

Acknowledgement

This study received funding support from the National Research Foundation of Thailand (NRF) and Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand.

References

- 1.Melis EH, Torres-Moreno R, Barbeau H, Lemaire ED. Analysis of assisted-gait characteristics in persons with incomplete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 1999;37(6):430–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National SCI Statistical Center. Facts & Figures at A Glance 2008 [cited 2011 Sep 2]

- 3.Bateni H, Maki BE. Assistive devices for balance and mobility: benefits, demands, and adverse consequences. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;86(1):134–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smidt GL, Mommens MA. System of reporting and comparing influence of ambulatory aids on gait. Phys Ther 1980;60(5):551–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ulkar B, Yavuzer G, Guner R, Ergin S. Energy expenditure of the paraplegic gait: comparison between different walking aids and normal subjects. Int J Rehabil Res 2003;26(3):213–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain NB, Higgins LD, Katz JN, Garshick E. Association of shoulder pain with the use of mobility devices in persons with chronic spinal cord injury. PMR 2010;2(10):896–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brotherton SS, Saunders LL, Krause JS, Morrisette DC. Association between reliance on devices and people for walking and ability to walk community distances among persons with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2012;35(3):156–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahoney JE, Sager MA, Jalaluddin M. Use of an ambulation assistive device predicts functional decline associated with hospitalization. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1999;54(2):M83–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Iersel MB, Munneke M, Esselink RA, Benraad CE, Olde Rikkert MG. Gait velocity and the timed-up-and-go test were sensitive to changes in mobility in frail elderly patients. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61(2):186–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson AB, Carnel CT, Ditunno JF, Read MS, Boninger ML, Schmeler MR, et al. Outcome measures for gait and ambulation in the spinal cord injury population. J Spinal Cord Med 2008;31(5):487–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Hedel HJ, Wirz M, Dietz V. Standardized assessment of walking capacity after spinal cord injury: the European network approach. Neurol Res 2008;30(1):61–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam T, Noonan V, Eng J. A systematic review of functional ambulation outcome measures in spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2008;46:246–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Hedel HJ, Wirz M, Dietz V. Assessing walking ability in subjects with spinal cord injury: validity and reliability of 3 walking tests. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;86(2):190–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mong Y, Teo TW, Ng SS. 5-Repetition sit-to-stand test in subjects with chronic stroke: reliability and validity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010;91(3):407–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poncumhak P, Saengsuwan J, Kumruecha W, Amatachaya S. Reliability and validity of three functional tests in ambulatory patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2013;51(3):214–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saensook W, Poncumhak P, Saengsuwan J, Mato L, Kamruecha W, Amatachaya S. Discriminative ability of the 3 functional tests in independent ambulatory patients with spinal cord injury who walked with and without ambulatory assistive devices. J Spinal Cord Med 2014;37(2):212–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lord SR, Murray SM, Chapman K, Munro B, Tiedemann A. Sit-to-stand performance depends on sensation, speed, balance, and psychological status in addition to strength in older people. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2002;57(8):M539–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eriksrud O, Bohannon RW. Relationship of knee extension force to independence in sit-to-stand performance in patients receiving acute rehabilitation. Phys Ther 2003;83(6):544–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janssen WG, Bussmann HB, Stam HJ. Determinants of the sit-to-stand movement: a review. Phys Ther 2002;82(9):866–79 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whitney SL, Wrisley DM, Marchetti GF, Gee MA, Redfern MS, Furman JM. Clinical measurement of sit-to-stand performance in people with balance disorders: validity of data for the five-times-sit-to-stand test. Phys Ther 2005;85(10):1034–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed ‘Up & Go’: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991;39(2):142–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shumway-Cook A, Brauer S, Woollacott MH. Predicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults using the timed up & go test. Phys Ther 2000;80(9):896–903 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graham JE, Ostir GV, Fisher SR, Ottenbacher KJ. Assessing walking speed in clinical research: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract 2008;14(4):552–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finch E, Brooks D, Stratford P, Mayo N. Physical rehabilitation outcome measures: a guide to enhanced clinical decision making. Hamilton: BC Decker; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park SH, Goo JM, Jo CH. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve: practical review for radiologists. Korean J Radiol 2004;5(1):11–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akobeng AK Understanding diagnostic tests 3: receiver operating characteristic curves. Acta Paediatr 2007;96(5):644–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fan J, Upadhye S, Worster A. Understanding receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. CJEM 2006;8(1):19–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leo M An NCME instructional module on standard error of measurement. ITEM 1991:33–41 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bland J, Altman D. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986;1:307–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Hedel HJ Gait speed in relation to categories of functional ambulation after spinal cord injury. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2009;23(4):343–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zorner B, Blanckenhorn WU, Dietz V, Curt A. Clinical algorithm for improved prediction of ambulation and patient stratification after incomplete spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2010;27(1):241–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardy S, Perera S, Roumani Y, Chandler J, Studenski S. Improvement of usual gait speed predicts better survival in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:1727–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beauchet O, Fantino B, Allali G, Muir SW, Montero-Odasso M, Annweiler C. Timed up and go test and risk of falls in older adults: a systematic review. J Nutr Health Aging 2011;15(10):933–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunter KB, White KN, Hayes WC, Snow CM. Functional mobility discriminates nonfallers from one-time and frequent fallers. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2000;55(11):M672–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buatois S, Miljkovic D, Manckoundia P, Gueguen R, Miget P, Vancon G, et al. Five times sit to stand test is a predictor of recurrent falls in healthy community-living subjects aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56(8):1575–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Hedel HJ, Dietz V, Curt A. Assessment of walking speed and distance in subjects with an incomplete spinal cord injury. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2007;21(4):295–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]