Abstract

Background

Commonly used inhalational hypnotics, such as sevoflurane, are pro-inflammatory, whereas the intravenously administered hypnotic agent propofol is anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative. A few clinical studies have indicated similar effects in patients. We examined the possible association between patient survival after radical cancer surgery and the use of sevoflurane or propofol anaesthesia.

Patients and methods

Demographic, anaesthetic, and surgical data from 2,838 patients registered for surgery for breast, colon, or rectal cancers were included in a database. This was record-linked to regional clinical quality registers. Cumulative 1- and 5-year overall survival rates were assessed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and estimates were compared between patients given propofol (n = 903) or sevoflurane (n = 1,935). In a second step, Cox proportional hazard models were calculated to assess the risk of death adjusted for potential effect modifiers and confounders.

Results

Differences in overall 1- and 5-year survival rates for all three sites combined were 4.7% (p = 0.004) and 5.6% (p < 0.001), respectively, in favour of propofol. The 1-year survival for patients operated for colon cancer was almost 10% higher after propofol anaesthesia. However, after adjustment for several confounders, the observed differences were not statistically significant.

Conclusion

Propofol anaesthesia might be better in surgery for some cancer types, but the retrospective design of this study, with uneven distributions of several confounders, distorted the picture. These uncertainties emphasize the need for a randomized controlled trial.

Keywords: Anaesthetics, intravenous, inhalational, neoplasm recurrence, local, epidemiology, survival

Introduction

There is converging evidence from animal studies and studies of human cell lines to indicate that different anaesthetics can have opposite effects on the immune system (1–7). Commonly used inhalational hypnotics, such as sevoflurane, are pro-inflammatory, whereas the intravenously administered hypnotic agent propofol is anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative. A few clinical studies have indicated similar effects in patients (8–11). Against that background it is not surprising that special interest has been paid to the effect of different anaesthetic techniques/procedures on cancer recurrence and patient survival after surgery (12,13).

Therefore, in this study we examined the possible association between survival from radical cancer surgery and the choice of hypnotic used, in a large cohort of patients undergoing cancer surgery between 1997 and 2010 at our hospital. We hypothesized that the 1- and 5-year survival rates after radical breast or colorectal cancer surgery under general anaesthesia would be higher in patients given the intravenously administered hypnotic propofol than in patients given the inhalational hypnotic sevoflurane.

Patients and methods

Patients

Adult patients at least 18 years of age were operated on for breast or colorectal cancers under general anaesthesia from 1 January 1998 to 31 March 2010 at the Central Hospital in Västerås, Sweden. The Regional Ethics Committee approved the study on 21 January 2009 (2008/350). This investigation was carried out as a single-centre, register-based, retrospective cohort study.

Data collection, extraction

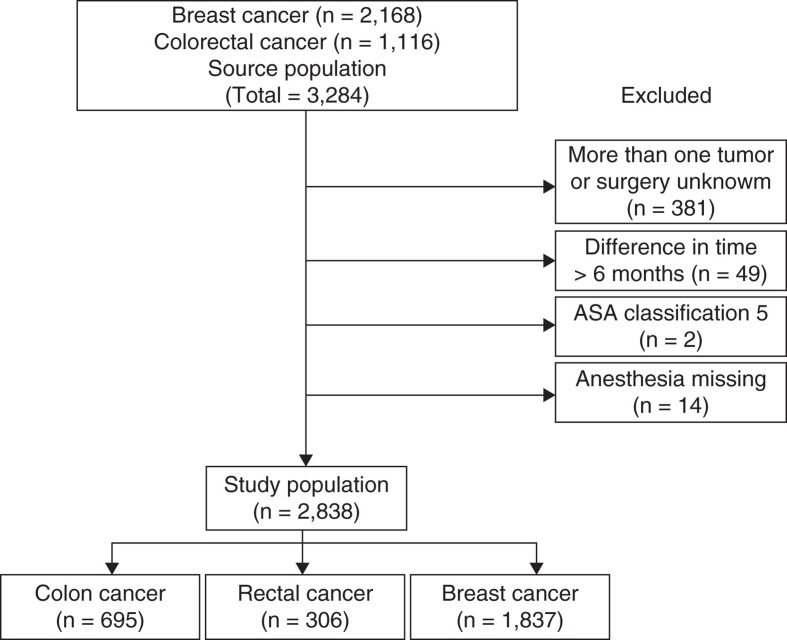

Patients were identified from a computerized administrative system, which included some demographic, anaesthetic, and surgical data. Data were available for all patients exposed to anaesthesia and surgery during the defined period and included the choice of anaesthetic. All in all, 3,284 patients registered for surgery for breast, colon, or rectal cancers were extracted from the register (Figure 1). Further demographic, anaesthetic, and surgical data of interest, specified below, were extracted from patient records and included in a database.

Figure 1.

Study population.

Registered data

Descriptive data

Sex, age, functional classification according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, cardiac failure, cardiac ischemia, and any smoking habit.

Anaesthesia-related data.

Use of propofol or sevoflurane (there were no restricting clinical guidelines for the choice), the use of adjuvant nitrous oxide (in use to the year 2000, mainly for breast surgery), any complementary epidural anaesthesia (for colorectal surgery), and the duration of anaesthesia.

Surgery-related data.

Type of cancer removed, duration of surgery, blood loss, red blood cell (RBC) transfusion amount (number of units), tumour stage, complementary treatment used, date and type (local, regional, or generalized) of relapse of cancer, and date of death.

Linking and matching of databases

The database was linked to the regional clinical quality registers at the Regional Cancer Centre (RCC) in Uppsala, Sweden, for confirmation of diagnosis and collection of tumour and clinical data. These registers have been found to be >97% complete, in comparison with the Swedish Cancer Register (SCR), to which reporting is mandatory by law. The SCR holds diagnoses only and contains no clinical information. The RCC registers include detailed information on the mode of detection of the cancer, histopathology results, cancer stage at diagnosis, other prognostic markers, and any complementary treatment given. Hence, complete oncologic and outcome data were available for all types of cancer included in the study. Data on type and stage of the cancer and the patients’ vital status were extracted, as well as different prognostic markers recorded in the oncologic registers.

For evaluating consistency, 476 patient records were double-checked for the rate of errors in data input.

Analyses

The main end-point was overall survival rate, comparing patients given propofol or sevoflurane. Survival time was defined as the interval between date of surgery and date of outcome, emigration, or end of follow-up on 31 September 2012. Kaplan–Meier estimates of patient survival were calculated for each cancer site and between propofol and sevoflurane. Cox regression with hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to assess risk of death for each cancer site, adjusted for uneven distribution of potential confounding variables. In the next step, we calculated relative survival, which was calculated by dividing observed survival of the cancer patients with expected rate in the general background population with corresponding sex, age, and year of diagnosis. Post hoc, we also calculated the HR for each cancer site restricted to a follow-up period of 3 years. All p values were two-sided, and statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using R version 10.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Statistical power

A clinically relevant absolute difference in 5-year survival of 5% was hypothesized. With the original data set of 3,284 patients and our assumptions of standard deviations, we had a 90% power to detect a 5% difference at 5 years at p < 0.05.

Results

After extraction of data from the patients’ records, excluding technical and other errors in the administrative system, or those who were anaesthetized more than once with different anaesthetics (Figure 1), there were 903 patients anaesthetized with propofol and 1,935 with sevoflurane. One case of a wrong code for the given anaesthetic was identified during double-checking of the data (476 files), which corresponded to a failure rate of 0.2%.

There was a shift over time towards a more frequent use of propofol (Table I). Thus, whereas less than 1% of the patients were given propofol during the first time-period (1997–2000), more than 85% were anaesthetized with propofol at the end (2007–2010) of the observation period. Sex and smoking habits were similar amongst the patient groups. Several potential confounders and effect modifiers were, however, found unequally distributed between the two anaesthetic groups: distribution of age at onset (colon; p < 0.01), ASA class (colon; p < 0.01), and a positive history of myocardial infarction (breast; p < 0.01).

Table I.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients operated for colon, rectal, or breast cancer between 1997 and 2010.

| Colon cancer |

Rectal cancer |

Breast cancer |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Propofol | Sevoflurane | Propofol | Sevoflurane | Propofol | Sevoflurane | |

| All patients | 179 | 516 | 104 | 202 | 620 | 1217 |

| Calendar period | ||||||

| 1997–2000 | 1 | 201 | 0 | 75 | 4 | 367 |

| 2001–2004 | 80 | 200 | 45 | 73 | 124 | 696 |

| 2005–2007 | 50 | 81 | 28 | 44 | 222 | 136 |

| 2008–2010 | 48 | 34 | 31 | 10 | 270 | 18 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 85 | 259 | 60 | 121 | 3 | 3 |

| Female | 94 | 257 | 44 | 81 | 617 | 1214 |

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||

| <59 years | 32 | 88 | 25 | 52 | 295 | 548 |

| 60–69 years | 61 | 112 | 34 | 60 | 163 | 300 |

| 70–79 years | 58 | 197 | 37 | 67 | 92 | 211 |

| >80 years | 28 | 119 | 8 | 23 | 70 | 158 |

| Smoking history | ||||||

| Never | 110 | 253 | 58 | 86 | 417 | 593 |

| Ex-smoker | 40 | 89 | 29 | 42 | 67 | 94 |

| Smoker | 25 | 57 | 13 | 29 | 109 | 189 |

| Cardiac failure | ||||||

| No history | 168 | 466 | 102 | 195 | 606 | 1164 |

| Positive history | 10 | 50 | 2 | 6 | 14 | 47 |

| Cardiac ischemia | ||||||

| No history | 149 | 405 | 95 | 181 | 590 | 1112 |

| Positive history | 29 | 111 | 8 | 20 | 29 | 102 |

| ASA classification | ||||||

| 1 | 18 | 52 | 21 | 32 | 182 | 384 |

| 2 | 114 | 261 | 61 | 123 | 355 | 630 |

| 3 | 42 | 175 | 21 | 45 | 77 | 178 |

| 4 | 4 | 28 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 17 |

As regards perioperative characteristics (Table II), it was found that the duration of anaesthesia was similar when comparing the two anaesthetic procedures as was the use of epidural anaesthesia (not used for breast cancer patients but frequently used for colon and rectal cancer patients) and figures for blood losses. Nitrous oxide was used to some extent in sevoflurane-anaesthetized breast cancer patients. Surgery went on for about 5 hours in the rectal cancer patients, whereas surgery for colon and breast cancers was less time-consuming (somewhat more than 3 and 1 h, respectively). There were, however, no major differences in duration of surgery between the two anaesthetic procedures used. Some of the colon cancer patients (20%) were taken care of as emergency operations. Sevoflurane anaesthesia was then preferentially used. Almost half of the rectal cancer patients were re-operated at least once, whereas colon and breast cancer patients were re-operated less frequently (about 15% and 25%, respectively). At re-operation, sevoflurane tended to be used more frequently, also in patients primarily anaesthetized with propofol.

Table II.

Perioperative characteristics of patients operated for colon, rectal, or breast cancer between 1997 and 2010.

| Colon cancer |

Rectal cancer |

Breast cancer |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Propofol | Sevoflurane | Propofol | Sevoflurane | Propofol | Sevoflurane | |

| Duration of anaesthesia | ||||||

| Mean (SD), minutes | 253 (83) | 230 (75) | 366 (93) | 349 (72) | 119 (41) | 110 (43) |

| Epidural anaesthesia | ||||||

| No | 11 | 88 | 2 | 5 | 620 | 1176 |

| Yes | 168 | 406 | 102 | 188 | 0 | 0 |

| Nitrous oxide | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | 7 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 305 |

| No | 155 | 463 | 90 | 179 | 533 | 792 |

| Blood loss | ||||||

| Mean (SD), mL | 350 (349) | 375 (384) | 815 (755) | 857 (551) | 85 (134) | 137 (172) |

| Transfusions | ||||||

| 1 | 34 | 94 | 17 | 45 | 6 | 26 |

| 2 | 24 | 66 | 17 | 39 | 1 | 12 |

| 3 | 6 | 12 | 9 | 11 | 0 | 2 |

| 4+ | 1 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 3 |

| Duration of surgery | ||||||

| Mean (SD), minutes | 204 (77) | 185 (71) | 309 (90) | 294 (69) | 86 (38) | 80 (40) |

| Type of surgery | ||||||

| Emergency | 11 | 129 | – | – | – | – |

| Elective | 168 | 387 | – | – | – | – |

| Re-operations | ||||||

| No re-operations | 148 | 453 | 59 | 124 | 480 | 891 |

| One or more re-operations | 31 | 63 | 45 | 78 | 140 | 326 |

| Type of anaesthesia (during re-operation) | ||||||

| Propofol | 12 | 9 | 20 | 19 | 103 | 49 |

| Sevoflurane | 17 | 50 | 25 | 57 | 34 | 270 |

| Other | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

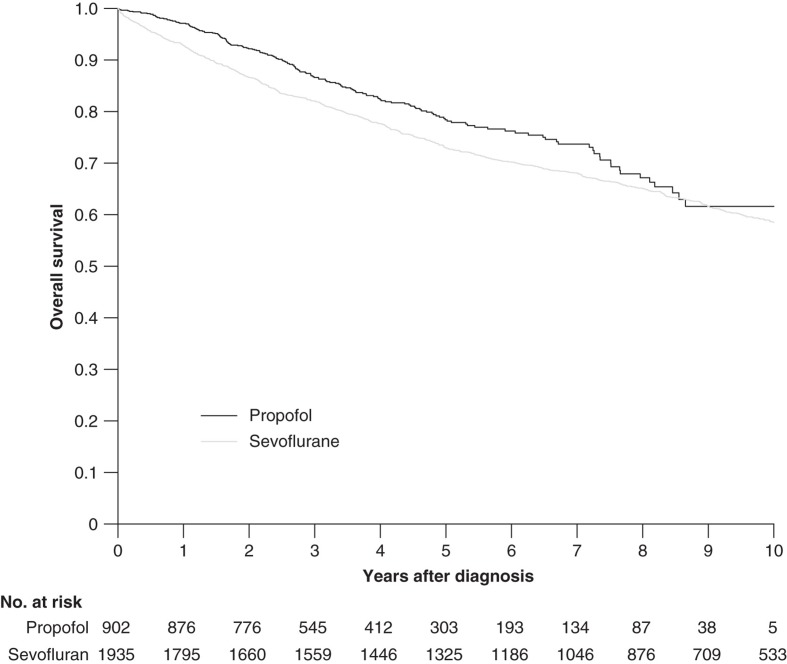

By use of Kaplan–Meier survival estimates there were differences observed in overall survival between patients anaesthetized with propofol and sevoflurane when data for all patients and cancer sites were combined (Figure 2). Thus, propofol-anaesthetized patients had a better overall survival (p = 0.004; log rank test). More detailed analysis of the data, i.e. rates of relative survival, revealed that propofol anaesthesia had been of advantage for the 1-year survival of patients diagnosed with colon and breast cancer but not for that of patients with rectal cancer (Table III). After 5 years, however, there was no difference in survival for patients suffering from breast cancer (Table III). Those differences in overall 1- and 5-year survival rates for all sites combined were 4.7% (p = 0.004) and 5.6% (p < 0.001), respectively, in favour of propofol. The intergroup differences were strengthened when adding to the analysis all patients given the same anaesthetic for one or more repeated operations (n = 512) (detailed data not shown).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve for survival after propofol- or sevoflurane-based anaesthesia for all cancer sites.

Table III.

Proportions of 1- and 5-year survival for patients anaesthetized with propofol or sevoflurane and the difference between anaesthesia groups for patients diagnosed with colon, rectal, or breast cancer between 1997 and 2010.

| Propofol (95% CI) | Sevoflurane (95% CI) | Difference in survival (propofol minus sevoflurane) (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-year survival | ||||

| All sites | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | 0.93 (0.92–0.94) | 0.04 (0.03–0.06) | p < 0.001 |

| Colon cancer | 0.93 (0.89–0.97) | 0.84 (0.81–0.87) | 0.09 (0.04–0.14) | p < 0.001 |

| Rectal cancer | 0.95 (0.91–0.99) | 0.96 (0.93–0.98) | –0.01 (–0.05–0.05) | n.s. |

| Breast cancer | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) | 0.03 (0.01–0.04) | p < 0.001 |

| 5-year survival | ||||

| All sites | 0.78 (0.75–0.82) | 0.73 (0.71–0.75) | 0.05 (0.02–0.09) | p < 0.01 |

| Colon cancer | 0.63 (0.56–0.72) | 0.53 (0.48–0.57) | 0.11 (0.02–0.20) | p < 0.05 |

| Rectal cancer | 0.73 (0.64–0.83) | 0.67 (0.60–0.74) | 0.06 (–0.06–0.17) | n.s. |

| Breast cancer | 0.84 (0.81–0.88) | 0.82 (0.80–0.85) | 0.02 (–0.02–0.06) | n.s |

CI = confidence interval; n.s. = non-significant.

However, following adjustment for confounders, the observed differences in overall survival were eliminated for all cancer sites (Table IV). A post hoc analysis of the HR restricted to a 3-year follow-up increased the difference between the two anaesthetic groups, but still lacked statistical significance. Thus, the HR for colon cancer decreased from 0.94 (95% CI, 0.71–1.25) to 0.86 (95% CI, 0.60–1.24) with propofol (HR for sevoflurane = 1.00).

Table IV.

Hazard ratios and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals for clinical characteristics that significantly differed in univariate analyses for patients diagnosed with colon, rectal, or breast cancer between 1997 and 2010.

| Colon cancer |

Rectal cancer |

Breast cancer |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

Univariate |

Multivariate |

Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||||

| HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | |

| Anaesthesia | ||||||||||||

| Sevoflurane | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Propofol | 0.74 | (0.60–0.93) | 0.94 0.93 |

(0.71–1.25) (0.71–1.21) |

0.80 | (0.52–1.22) | 0.83 0.87 |

(0.52–1.31) (0.55–1.37) |

0.84 | (0.65–1.08) | 1.33 1.31 |

(0.91–1.94) (0.93–1.91) |

| Calendar period | ||||||||||||

| 1997–2000 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | ref. | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| 2001–2004 | 0.88 | (0.72–1.08) | 1.00 | (0.77–1.29) | 1.00 | (0.66–1.51) | 1.06 | (0.68–1.65) | 1.11 | (0.89–1.39) | 0.97 | (0.69–1.37) |

| 2005–2007 | 0.74 | (0.56–0.97) | 0.80 | (0.58–1.11) | 0.88 | (0.51–1.51) | 0.86 | (0.50–1.50) | 0.61 | (0.42–0.87) | 0.60 | (0.35–1.02) |

| 2008–2010 | 0.61 | (0.40–0.94) | 0.80 | (0.39–1.62) | 0.45 | (0.16–1.28) | 0.46 | (0.06–3.54) | 0.49 | (0.27–0.88) | 0.20 | (0.03–1.52) |

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| 0–59 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 60–69 | 1.25 | (0.92–1.70) | 1.05 | (0.70–1.56) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 70–79 | 2.01 | (1.52–2.66) | 1.62 | (1.12–2.32) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| ≥80 | 3.60 | (2.68–4.83) | 2.54 | (1.73–3.73) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| ASA classification | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2 | 1.83 | (1.31–2.56) | 1.76 | (1.08–2.85) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 3 | 2.91 | (2.05–4.12) | 2.20 | (1.32–3.67) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4 | 4.53 | (2.78–7.39) | 2.99 | (1.61–5.54) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Epidural anaesthesia | ||||||||||||

| No | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | 0.50 | (0.39–0.64) | 0.79 | (0.57–1.09) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Type of surgery | ||||||||||||

| Emergency | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Elective | 0.51 | (0.40–0.64) | 0.61 | (0.45–0.81) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cardiac failure | ||||||||||||

| No history | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Positive history | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3.24 | (2.51–4.19) | 2.98 | (2.17–4.11) |

| Anaesthesia duration | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.01) | – | – | – | – | 1.00 | (1.00–1.01) | 1.00 | (0.99–1.02) |

| Blood loss | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.01 | (1.01–1.01) | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) |

| Stage at diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| I | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| II | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2.97 | (2.27–3.90) | 2.61 | (1.90–3.57) |

| III | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 8.57 | (5.83–12.59) | 5.67 | (3.61–8.90) |

| IV | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 10.59 | (6.13–18.29) | 6.80 | (3.61–12.85) |

| Nitrous oxide | ||||||||||||

| Yes | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.88 | (0.70–1.10) | 1.03 | (0.72–1.46) |

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; CI = confidence interval; HR = Cox proportion hazard ratio; HR in italic = adjusted for propensity scores.

Discussion

There is converging evidence from animal studies and studies of human cell lines that different anaesthetics might affect the immune system in different ways (1–7). Thus, commonly used inhalational hypnotics such as sevoflurane are pro-inflammatory, whereas the intravenously administered hypnotic agent propofol is anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative. Indeed, there are a number of clinical reports in support of this (8–11). More specifically, previous studies have demonstrated immunological effects of different anaesthetics on monocytes, macrophages, natural killer cells, cytotoxic T cells, and T helper cells (4–6,10,14). By affecting T helper cells, anaesthetics indirectly affect the production of anti-inflammatory mediators such as interleukin-10. Anaesthetics also influence the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1 and -6. Moreover, the effects could be indirect by blocking or not blocking the surgical stress response via the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous system (15,16). Thus, stress hormones such as catecholamines and cortisol will mediate inhibitory effects on immune functions. The neuroendocrine system, together with cytokines, augments these immunosuppressive effects in a highly complex way. Taken together, results from previous research support the hypothesis that inhalational hypnotics are immunosuppressive in mice (6,17) as well as in humans (4,5).

There is also ample evidence to suggest that there are other adverse effects of inhalational hypnotics that could be attributed to immunological processes. For example, inhalational hypnotics seem to increase the occurrence of cancer metastases in mice and rats (6,7,17,18). Such adverse effects have, however, not been found for propofol. In contrast, propofol seems to inhibit tumour growth and reduce the tendency to induce metastases in mice (3,19).

It should also be kept in mind that genotoxic agents might impair patients’ survival after cancer surgery because of the well-known connection between DNA damage and oncogenesis. The potential genotoxicity of inhalational anaesthetic agents in patients and in exposed staff in operating rooms has been studied both in vitro (20,21) and in vivo (22–25). Thus, a dose–response relationship between inhalational agent exposure and DNA damage has been suggested (25). Inhalational agents seem to be consistently genotoxic, whereas the less studied propofol seems not to be so (22,24).

It was against this background that we planned our retrospective study. Just a few departments have applied a mixed use of hypnotics for a prolonged time-period, which has given us a unique opportunity to perform this type of comparative study. The use of propofol, which was marketed later than sevoflurane, was uncommon to start with but increased over time, thus reducing the observation time for this group of patients. This also introduced time as a potential confounder, assuming that cancer care in general has improved in time (26). The overall mortality rate in our region for patients with breast, colon, or rectal cancer decreased by 7.6%, comparing the first (1997–1999) and last periods (2007–2009) in our study. It is difficult to estimate to what extent this general evolution in cancer care contributed to the better results for the propofol group.

Red blood cell (RBC) transfusions might have affected patient survival rates after cancer surgery, due to an immunosuppressive effect from such allogeneic material. Several possible mediators may be active: allogeneic mononuclear cells, white-blood-cell-derived soluble mediators, and/or soluble human leukocyte antigen peptides circulating in allogeneic plasma (27,28). We identified those patients having perioperative RBC transfusions, controlled the distribution between the two groups, and found no statistically significant difference.

Although increasing age and higher ASA class significantly affected outcomes in the regression model, the contribution of an uneven distribution of age and ASA class to the observed difference in outcome between the two anaesthetic groups was small, taking into consideration the relatively small numbers in the subgroups with the highest HR values (Tables I and IV). The higher proportion of emergency cases given sevoflurane for colon cancer was substantial (25.0% versus 6.1%). This contributed to the results in the multivariate analysis, and the difference in HR was 40% (Table IV). This is probably especially valid for the difference in 1-year survival rates, assuming that emergency surgery will affect short-term survival more. However, the difference between the two hypnotics in the 5-year survival was not inferior to the 1-year result: rather the opposite, which confuses the discussion.

Morphine use postoperatively inhibits the immune response (27,29,30). However, we have no reason to suspect an uneven administration of postoperative morphine to the two study groups. This was, however, not controlled for during data evaluation because we did not have access to the drug documentation system for the surgical wards. Synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, alfentanil, and remifentanil, all used intra-operatively, have been proven not to suppress the immune response (31,32). On the contrary, these synthetic opioids might have positive effects in this context (33).

Nitrous oxide is supposed to impair the immune defence, and it also impairs DNA production by inhibition of the vitamin B12 component of methionine synthetase (7,34,35). The authors of a prospective trial were unable to confirm any impact from nitrous oxide on survival after colorectal surgery (36). However, that trial had limited power, being aimed originally to study postoperative infections. Nonetheless, we stopped the use of nitrous oxide in the mid-1980s for a number of surgical procedures, among them abdominal surgery. However, we continued to use nitrous oxide until the year 2000 for breast cancer surgery (37). Therefore, nitrous oxide was a potential confounder for a part of our study population. Moreover, the distribution was highly skewed with 27.8% versus 0.9% in patients anaesthetized with sevoflurane or propofol, respectively. Nevertheless, the regression model indicated no contribution from nitrous oxide to the results.

Epidural anaesthesia might be beneficial for survival from cancer surgery (12,13,38). The proportion of patients given epidural anaesthesia for colon cancer was higher in patients given propofol—93.9% versus 82.2%—and the HR value could be interpreted to indicate a beneficial effect from epidural anaesthesia, but it was not statistically significant. The proportion of repeat operations was higher for patients with colon cancer in the propofol group (17.3% versus 12.2%). The impact of repeat operations on survival has not been investigated thoroughly, but it is reasonable to assume some impact. However, the number of patients involved was low.

Selection bias is an inherent major disadvantage in every retrospective study. Here, the risk was considered low because of the non-selective use of the hypnotics, with no guidelines directing the use of a certain drug to a specific group of patients. In all, there were 4.7% more patients with a positive history of myocardial infarction in the sevoflurane group (breast cancer surgery). This relatively small difference does not support the choice of sevoflurane for myocardial ‘protection’.

The Cox HR factor, calculated to assess the risk of death for each cancer site with adjustment of uneven distributions of potential confounding variables, included the whole observation period, which introduces the question of ‘over-adjustment’. Obviously, survival curves for two populations must meet at some point, and for patients with colon cancer this happened after 8 years. To reduce the impact of a time-span in which the two curves meet, we calculated the HR at 3 years after surgery. This increased the difference in survival between the two anaesthetic groups, but still without being statistically significant.

All in all, we found that patients anaesthetized with propofol had longer overall survival rates than patients anaesthetized with sevoflurane when data for all patients and cancer sites were combined. However, this finding lost statistical significance after adjustment for confounders and effect modifiers. Thus, the results of our study do not support conclusions of other studies, claiming that survival might be higher after propofol anaesthesia. Based on the current results, we have made a power analysis for a prospective study. It was found that we will need at least 3,000 patients with colon cancer. This strongly indicates that the current study was underpowered, leaving us with a somewhat vague conclusion. Since undesired effects from anaesthesia on survival have strong relevance for overall cancer treatment, any factor that can affect survival in the order of 5% or more must be investigated. At some institutions, actions have already been taken by changing to propofol anaesthesia for cancer surgery, despite the lack of strong evidence (39). Therefore, we are obliged to plan for a randomized, prospective, controlled trial.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the County Council of Västmanland (LTV140721, LTV214381) and Uppsala-Örebro Regional Research Council (RFR71761, RFR230021).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: Mats Enlund has received lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Baxter, GlaxoSmithKlein, and Sedana Medical AB. The other authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Inada T, Kubo K, Kambara T, Shingu K. Propofol inhibits cyclo-oxygenase activity in human monocytic THP-1 cells . Can J Anaesth. 2009;56:222–9. doi: 10.1007/s12630-008-9035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inada T, Yamanouchi Y, Jomura S, Sakamoto S, Takahashi M, Kambara T, et al. Effect of propofol and isoflurane anaesthesia on the immune response to surgery . Anaesthesia. 2004;59:954–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kushida A, Inada T, Shingu K. Enhancement of antitumor immunity after propofol treatment in mice . Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2007;29:477–86. doi: 10.1080/08923970701675085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loop T, Dovi-Akue D, Frick M, Roesslein M, Egger L, Humar M, et al. Volatile anesthetics induce caspase-dependent, mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in human T lymphocytes in vitro . Anesthesiology. 2005;102:1147–57. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200506000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuoka H, Kurosawa S, Horinouchi T, Kato M, Hashimoto Y. Inhalation anesthetics induce apoptosis in normal peripheral lymphocytes in vitro . Anesthesiology. 2001;95:1467–72. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200112000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melamed R, Bar-Yosef S, Shakhar G, Shakhar K, Ben-Eliyahu S. Suppression of natural killer cell activity and promotion of tumor metastasis by ketamine, thiopental, and halothane, but not by propofol: mediating mechanisms and prophylactic measures . Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1331–9. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000082995.44040.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shapiro J, Jersky J, Katzav S, Feldman M, Segal S. Anesthetic drugs accelerate the progression of postoperative metastases of mouse tumors . J Clin Invest. 1981;68:678–85. doi: 10.1172/JCI110303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilliland HE, Armstrong MA, Carabine U, McMurray TJ. The choice of anesthetic maintenance technique influences the antiinflammatory cytokine response to abdominal surgery . Anesth Analg. 1997;85:1394–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199712000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ke JJ, Zhan J, Feng XB, Wu Y, Rao Y, Wang YL. A comparison of the effect of total intravenous anaesthesia with propofol and remifentanil and inhalational anaesthesia with isoflurane on the release of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in patients undergoing open cholecystectomy . Anaesth Intensive Care. 2008;36:74–8. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0803600113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotani N, Hashimoto H, Sessler DI, Kikuchi A, Suzuki A, Takahashi S, et al. Intraoperative modulation of alveolar macrophage function during isoflurane and propofol anesthesia . Anesthesiology. 1998;89:1125–32. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199811000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneemilch CE, Ittenson A, Ansorge S, Hachenberg T, Bank U. Effect of 2 anesthetic techniques on the postoperative proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine response and cellular immune function to minor surgery . J Clin Anesth. 2005;17:517–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2004.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biki B, Mascha E, Moriarty DC, Fitzpatrick JM, Sessler DI, Buggy DJ. Anesthetic technique for radical prostatectomy surgery affects cancer recurrence: a retrospective analysis . Anesthesiology. 2008;109:180–7. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31817f5b73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cummings KC, 3rd, Xu F, Cummings LC, Cooper GS. A comparison of epidural analgesia and traditional pain management effects on survival and cancer recurrence after colectomy: a population-based study . Anesthesiology. 2012;116:797–806. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31824674f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woods GM, Griffiths DM. Reversible inhibition of natural killer cell activity by volatile anaesthetic agents in vitro . Br J Anaesth. 1986;58:535–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/58.5.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ben-Eliyahu S, Shakhar G, Page GG, Stefanski V, Shakhar K. Suppression of NK cell activity and of resistance to metastasis by stress: a role for adrenal catecholamines and beta-adrenoceptors . Neuroimmunomodulation. 2000;8:154–64. doi: 10.1159/000054276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graziola E, Elena G, Gobbo M, Mendez F, Colucci D, Puig N. Stress, hemodynamic and immunological responses to inhaled and intravenous anesthetic techniques for video-assisted laparoscopic cholecystectomy . Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2005;52:208–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lundy J, Lovett EJ, 3rd, Hamilton S, Conran P. Halothane, surgery, immunosuppression and artificial pulmonary metastases . Cancer. 1978;41:827–30. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197803)41:3<827::aid-cncr2820410307>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moudgil GC, Singal DP. Halothane and isoflurane enhance melanoma tumour metastasis in mice . Can J Anaesth. 1997;44:90–4. doi: 10.1007/BF03014331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mammoto T, Mukai M, Mammoto A, Yamanaka Y, Hayashi Y, Mashimo T, et al. Intravenous anesthetic, propofol inhibits invasion of cancer cells . Cancer Lett. 2002;184:165–70. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaloszynski P, Kujawski M, Wasowicz M, Szulc R, Szyfter K. Genotoxicity of inhalation anesthetics halothane and isoflurane in human lymphocytes studied in vitro using the comet assay . Mutat Res. 1999;439:199–206. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(98)00195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karpinski TM, Kostrzewska-Poczekaj M, Stachecki I, Mikstacki A, Szyfter K. Genotoxicity of the volatile anaesthetic desflurane in human lymphocytes in vitro, established by comet assay . J Appl Genet. 2005;46:319–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braz MG, Magalhaes MR, Salvadori DM, Ferreira AL, Braz LG, Sakai E, et al. Evaluation of DNA damage and lipoperoxidation of propofol in patients undergoing elective surgery . Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009;26:654–60. doi: 10.1097/eja.0b013e328329b12c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoerauf KH, Wiesner G, Schroegendorfer KF, Jobst BP, Spacek A, Harth M, et al. Waste anaesthetic gases induce sister chromatid exchanges in lymphocytes of operating room personnel . Br J Anaesth. 1999;82:764–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/82.5.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krause TK, Jansen L, Scholz J, Bottcher H, Wappler F, Burmeister MA, et al. Propofol anesthesia in children does not induce sister chromatid exchanges in lymphocytes . Mutat Res. 2003;542:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiesner G, Schiewe-Langgartner F, Lindner R, Gruber M. Increased formation of sister chromatid exchanges, but not of micronuclei, in anaesthetists exposed to low levels of sevoflurane . Anaesthesia. 2008;63:861–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Socialstyrelsen [National Board of Health and Welfare] 2011. Dödsorsaker [Causes of Death] [Art. nr. 2011-3-22]. Socialstyrelsen [Stockholm]

- 27.Flores LR, Dretchen KL, Bayer BM. Potential role of the autonomic nervous system in the immunosuppressive effects of acute morphine administration . Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;318:437–46. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00788-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vamvakas EC, Blajchman MA. Transfusion-related immunomodulation (TRIM): an update . Blood Rev. 2007;21:327–48. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freier DO, Fuchs BA. Morphine-induced alterations in thymocyte subpopulations of B6C3F1 mice . J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265:81–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeager MP, Colacchio TA, Yu CT, Hildebrandt L, Howell AL, Weiss J, et al. Morphine inhibits spontaneous and cytokine-enhanced natural killer cell cytotoxicity in volunteers . Anesthesiology. 1995;83:500–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199509000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bilfinger TV, Fimiani C, Stefano GB. Morphine’s immunoregulatory actions are not shared by fentanyl . Int J Cardiol. 1998;64:S61–6. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(98)00037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jaeger K, Scheinichen D, Heine J, André M, Bund M, Piepenbrock S, et al. Remifentanil, fentanyl, and alfentanil have no influence on the respiratory burst of human neutrophils in vitro . Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1998;42:1110–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1998.tb05386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yeager MP, Procopio MA, DeLeo JA, Arruda JL, Hildebrandt L, Howell AL. Intravenous fentanyl increases natural killer cell cytotoxicity and circulating CD16(+) lymphocytes in humans . Anesth Analg. 2002;94:94–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200201000-00018. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hadzic A, Glab K, Sanborn KV, Thys DM. Severe neurologic deficit after nitrous oxide anesthesia . Anesthesiology. 1995;83:863–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199510000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koblin DD. Nitrous oxide: a cause of cancer or chemotherapeutic adjuvant? . Semin Surg Oncol. 1990;6:141–7. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980060304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fleischmann E, Marschalek C, Schlemitz K, Dalton JE, Gruenberger T, Herbst F, et al. Nitrous oxide may not increase the risk of cancer recurrence after colorectal surgery: a follow-up of a randomized controlled trial . BMC Anesthesiol. 2009;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Enlund M, Edmark L, Revenas B. Ceasing routine use of nitrous oxide-a follow up . Br J Anaesth. 2003;90:686–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gottschalk A, Ford J, Regelin C, You J, Mascha E, Sessler DI, et al. Association between epidural analgesia and cancer recurrence after colorectal cancer surgery . Anesthesiology. 2010;113:27–34. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181de6d0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gordon RJ. Anesthesia dogmas and shibboleths: barriers to patient safety? . Anesth Analg. 2012;114:694–9. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182455b86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]