Abstract

Autophagosomes delivers cytoplasmic constituents to lysosomes for degradation while inflammasomes are molecular platforms activated by infection or stress that regulate the activity of caspase-1 and the maturation of interleukin 1β (IL-1β) and IL-18. Here we show that the induction of AIM2 or NLRP3 inflammasomes in macrophages triggered RalB activation and autophagosome formation. The induction of autophagy did not depend upon ASC or capase-1, but was dependent on the presence of the inflammasome sensor. Blocking autophagy potentiated inflammasome activity while stimulating autophagy limited it. Assembled inflammasomes underwent ubiquitination and recruited the autophagic adaptor p62, which assisted their delivery to autophagosomes. Our data indicate that autophagy accompanies inflammasome activation to temper inflammation by eliminating active inflammasomes.

Keywords: inflammasome, macrophage, autophagy, signal transduction, ubiquitination

Autophagy is a cellular response to starvation as well as a quality control system that can deliver damaged organelles and long-lived proteins from cytoplasm to lysosomes for clearance1. Autophagy helps clear intracellular protozoa, bacteria, and viruses and functions in antigen presentation2–5. Defects in autophagy are linked to numerous human diseases and to immune cell function. Conserved protein kinases, lipid kinases, and ubiquitin-like protein conjugation networks control autophagosome formation and cargo recruitment1. The activation of the Ras-like small G-protein RalB is sufficient to promote autophagosome formation6. By direct binding to Exo84, RalB induces the assembly of catalytically active ULK1 and Beclin-1 phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) complexes on the exocyst, a requirement for isolation membrane formation and maturation6. In macrophages, autophagy can be triggered by the engagement of Toll-like receptors (TLR)7–9. TLRs recognize specific molecular patterns that are present in microbial components and they trigger intracellular signals through homotypic interactions with proximal adaptor proteins such as MyD8810,11. In turn, MyD88 can interact with Beclin-1, a key component of the class III PI3K complex that initiates autophagosome formation8. One mechanism by which intracellular targets are delivered to autophagosomes is via autophagic adapter proteins. One such protein, p62, recognizes polyubiquitinated targets including bacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Using separate domains, p62 can bind ubiquitin and LC3. Following processing, LC3 is localized in autophagosome membranes12–14.

Inflammasomes are multiprotein complexes containing one or more Nod-like receptors (NLRs) that are activated following cellular infection or stress and trigger capase-1 activation and the maturation of IL-1β and IL-18 to engage innate immune defenses15. A strong association between dysregulated inflammasome activity and certain human inflammatory diseases underscores the importance of this pathway in innate immune responses. Various inflammasome complexes are triggered by distinct stimuli. The NLRP1 inflammasome is activated by anthrax lethal toxin, the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated by a broad range of toxic stimuli, the IPAF inflammasome is triggered by bacterial flagellin and the AIM2 inflammasome is essential for host defense against certain intracellular bacteria and DNA viruses15. The AIM2 inflammasome has been well characterized and is composed of AIM2, ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase activation and recruitment domain), and caspase-1. AIM2 binds dsDNA of both endogenous and microbial origin through its HIN200 domain and upon activation it oligomerizes and recruits the adaptor ASC through homophilic pyrin domain (PYD) interactions. ASC associates with pro-caspase-1 via CARD-CARD (caspase activation and recruitment domain) interactions, a step needed to induce caspase-1 activation16–19. The activation of caspase-1 results in the cleavage of the IL-1β precursor to its mature form20. The lack of this pathway has pathophysiological consequences as Aim2−/− mice are extremely susceptible to infections with Francisella tularensis, the causative agent of tularemia21,22.

Autophagy blockade by genetic deletion of Atg16L1 makes normally poorly responsive macrophages sensitive to TLR4-induced inflammasome activation23. Likely as a consequence of enhanced inflammasome activity, Atg16L1−/− mice suffer severe dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis that can be alleviated by neutralizing IL-1β and IL-1823. These observations and others24 prompted us to investigate the relationship between autophagy and inflammasome activity. We found that various inflammasome stimuli triggered autophagy in macrophages by activating RalB nucleotide exchange. Assembled inflammasomes underwent ubiquitination and recruited the autophagic adaptor p62, which assisted their delivery to autophagosomes. The manipulation of autophagy affected the level of IL-1βproduction by macrophages stim ulated to trigger inflammasome activation.

RESULTS

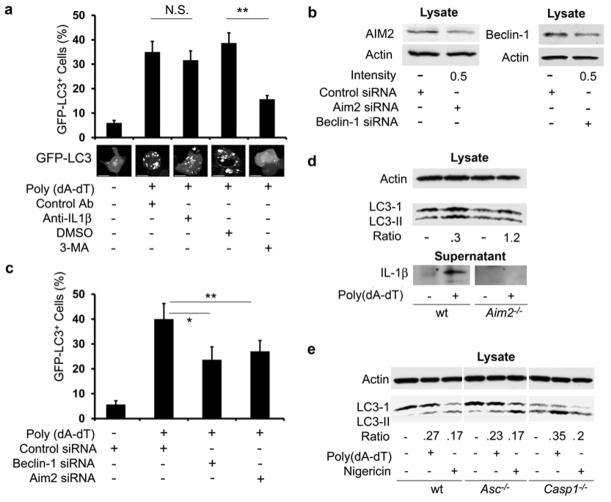

Induction of AIM2 and NLRP3 inflammasomes triggers autophagy

To check whether autophagy accompanied AIM2 inflammasome activation we used the human monocyte cell line THP-1 stably expressing the autophagy marker GFP-LC3. When autophagosomes form, GFP-LC3 is processed and recruited to the autophagosomal membrane, where it can be imaged by confocal microscopy25. We induced AIM2 inflammasomes in macrophages differentiated from THP-1 cells by transfecting dsDNA in the form of poly(dA-dT). Autophagosome formation was observed six hours after transfection (Fig. 1a). Autophagosome induction did not occur when dsDNA was omitted from the transfection cocktail. Poly(dA-dT) exposure induced an increase in the number of cells with autophagosomes as well as the number of autophagosomes per cell (Supplementary Fig. 1). Addition of the lysosome inhibitors E64d and Pepstatin A enhanced the number of cells with GFP-LC3 dots triggered by poly(dA-dT) exposure (Supplementary Fig. 1). Because IL-1β can trigger autophagy in murine macrophages26, we examined whether autophagosome formation in this system depended upon IL-1β production. Neutralization of IL-1β on had no effect no on autophagosome formation over the time-frame we examined (Fig. 1a). Addition of the PI3K inhibitor 3-methyladenine (3-MA), which is known to block autophagosome formation27, inhibited the poly(dA-dT)-induced autophagic response (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Induction of inflammasomes induces autophagy. (a) Induction of GFP dots in differentiated THP-1 cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 following transfection with 1.5 μg/ml poly(dA-dT) for 6h and exposed to 3-MA (5mM), antibodies that neutralize IL-1β, or control antibodies. Top, quantitation of GPF-LC3 dots. Bottom, representative images of individual cells. NS-not significant, ** - p < 0.01, *- p< 0.05. Scale bars, 10 μm. (b) AIM2 and Beclin-1 expression in cells transfected with AIM2, Beclin-1 and control siRNA. The ratio of targeted to control is shown below. (c) Induction of GFP dots in differentiated THP-1 cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 and treated with indicated siRNAs, quantitated 6h after transfection with poly(dA-dT). (d) LC3-I and LC3-II expression and IL-1β production in Aim2−/− or wild-type (WT) BMDMs transfected or not with poly(dA-dT) for 6 hrs and immunoblotted for LC3. The ratio shown is the induced LC3-I/LC3-II ratio divided by the basal LC3-I/LC3-II ratio. IL-1β production was measured in the supernatant following overnight culture. Data shown is representative of four repeats using two separate BMDM preparations. (e) LC3-I and LC3-II expression in Asc−/−, Casp1−/− or wild-type BMDMs primed with LPS (20 ng/ml) and then transfected with poly(dA-dT) or treated with nigericin for 4 h. The ratio is the induced LC3-I/LC3-II ratio divided by the basal LC3-I/LC3-II ratio. Shown is one representative LC3-I and LC3-II immunoblot of four repeats using two separate BMDM preparations. Data are from three separate experiments (a, b; means +/− s.d.).

To determine the involvement of Beclin-1 and AIM2 in the poly(dA-dT) induced autophagosome formation, we reduced their protein expression by siRNA targeting. The transfection efficiency achieved in the target cells was approximately 40–50%, resulting in a 50% reduction in AIM2 and Beclin-1 expression in the cell lysates (Fig. 1b). Co-transfection of poly(dA-dT) together with siRNA for Beclin-1 or AIM2 impaired the levels of autophagosome formation (Fig. 1c). To confirm these results, we stimulated bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) prepared from either wild-type or Aim2−/− mice with poly(dA-dT) and immunoblotted the cell lysates for LC3. LC3 processing (indicated by the increase in the ratio between LC3-II and LC3-I) was enhanced in the lysates from wild-type BMDM, but not in Aim2−/− BMDM. To allow a comparison of the different cell preparations, we divided the induced LC3-I/LC3-II ratio by the basal LC3-I/LC3-II ratio for each cell preparation. We did not detect any IL-1β protein in the supernatants of poly(dA-dT) stimulated Aim2−/− BMDM (Fig. 1d).

To address whether autophagosome formation occurred as a consequence of NLRP3 inflammasome activation, we stimulated differentiated THP-1 cells with uric acid crystals or nigericin28–30. Exposure to these stimuli also triggered autophagy, which was sensitive to inhibition by 3-MA, but insensitive to IL-1β neutralization (Supplementary Fig. 2). To test the involvement of ASC or caspase-1 in the induction of autophagy following inflammasome activation, we used BMDM from Asc(Pycard)−/− or Casp1−/− mice31,32. Exposure to poly(dA-dT) or nigericin triggered a similar degree of LC3 processing in wild-type, Asc−/−, and Casp1−/− BMDM (Fig. 1e). These results indicate that the initial induction of autophagy in response to stimuli that trigger AIM2 inflammasome activation is dependent on the inflammasome sensor, but does not require the completed assembly of the inflammasomes or IL-1β production.

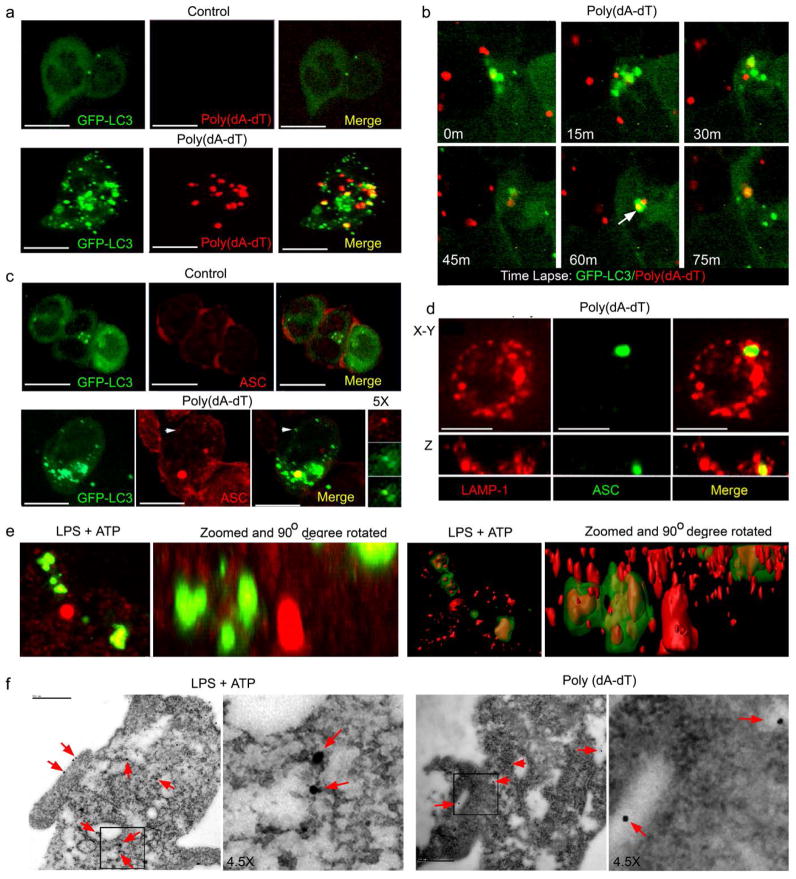

Inflammasomes colocalize with autophagosomes

To visualize the potential interaction between AIM2 inflammasomes and autophagosomes we used immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. Because AIM2 binds and co-localizes with cytosolic DNA, we initially used fluorescently labeled DNA as surrogate marker for the AIM2 inflammasomes. The cytosolic transfected poly(dA-dT) labeled with Cy3 (red) coalesced into fluorescent red dots following transfection into the differentiated THP-1 cells that stably expressed GFP-LC3. The labeled poly(dA-dT) cytosolic dots partially co-localized with the GFP-LC3 autophagosomes (Fig. 2a). Time-lapse imaging detected the merging of GFP-LC3 delineated autophagosomes with the Cy3-DNA dots (Fig. 2b). We also stimulated differentiated THP-1 cells expressing GFP-LC3 with non-labeled poly(dA-dT) and immunostained the AIM2 inflammasome adaptor ASC to visualize inflammasomes. We detected a partial overlap between ASC structures and GFP-LC3 labeled autophagosomes (Fig 2c). Mature autophagosomes merge with lysosomes resulting in degradation of the contents of the autophagosome1. We could detect ASC labeled structures surrounded by lysosome associated membrane protein (Lamp-1) expressing vesicles (Fig. 2d) suggesting that autophagosomes with inflammasome components merged with lysosomes.

Figure 2.

Inflammasome activation leads to partial co-localization of autophagosomes and inflammasomes. (a) Confocal microscopy of differentiated THP-1 GFP-LC3 cells transfected with Cy3 labeled 1.5 μg/ml poly(dA-dT) for 3h. The yellow dots (Merge panel) indicate co-localization between green (LC-3) and red (Cy3) signals. (b) Confocal microscopy of differentiated THP-1 GFP-LC3 cells transfected with Cy3-poly(dA-dT) imaged every 15 minutes starting 1h after transfection. Coalescence between the Cy3 and GFP signal is shown in 60 and 75 minute panels. (c) Confocal microscopy of differentiated THP-1 GFP-LC3 cells transfected with poly(dA-dT) or sham transfected, fixed, and immunostained for ASC (red). The insert to the right is a 5X zoom of the indicated areas. (d) Confocal microscopy of differentiated THP-1 cells transfected with poly(dA-dT) and immunostained for Lamp-1 and ASC. Below each image is a z-axis projection. (e) Confocal microscopy of differentiated THP-1 GFP-LC3 cells treated with LPS (500ng/ml) +ATP (3mM) for 2h, immunostained for ASC (red), and imaged. The 1st and 2nd panels are 3D volume renderings reconstructed from z-stack images (2nd panel is rotated 90O and zoomed 3x). The same images are shown as a surface segmentation model in the 3rd and 4th panels. Scale bars shown are 10 μm. (f) Electron microscopy of differentiated THP-1 cells stimulated with LPS + ATP or transfected with poly(dA-dT) for 2h and immunostained for ASC visualized with 15 nm gold conjugated protein A. ASC immunostaining is indicated with red arrows. Scale bars are 500 nm.

To determine whether NLRP3 inflammasomes also co-localized with autophagosomes, we treated differentiated THP-1 cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 with LPS and ATP. While LPS is by itself a poor activator of inflammasomes, it potentiates the activation of the NLPR3 inflammasome by the danger signal ATP28. Because NLPR3 inflammasomes also utilize ASC, we examined the localization of ASC-containing cytosolic dots with respect to the GFP-LC3 labeled autophagosomes in LPS+ATP stimulated cells. Surface rendering software to process the z-section stack of images allowed the detection of ASC structures completely enclosed within structures resembling autophagosomes (Fig. 2e, supplement video 1). Next, THP-1 cells in which the NLRP3 and AIM2 inflammasome had been activated were visualized by electron microscopy. Ultrathin slices were immunostained for ASC. Both poly(dA-dT) and LPS+ATP exposure led to readily identifiable autophagosomes within the cytosol. In numerous instances, ASC immunostaining was located within the autophagosome (Fig. 2f). Some ASC immunoreactivity was also detected along the plasma membrane (Fig. 2F), which correlated with results obtained by confocal microscopy (data not shown).

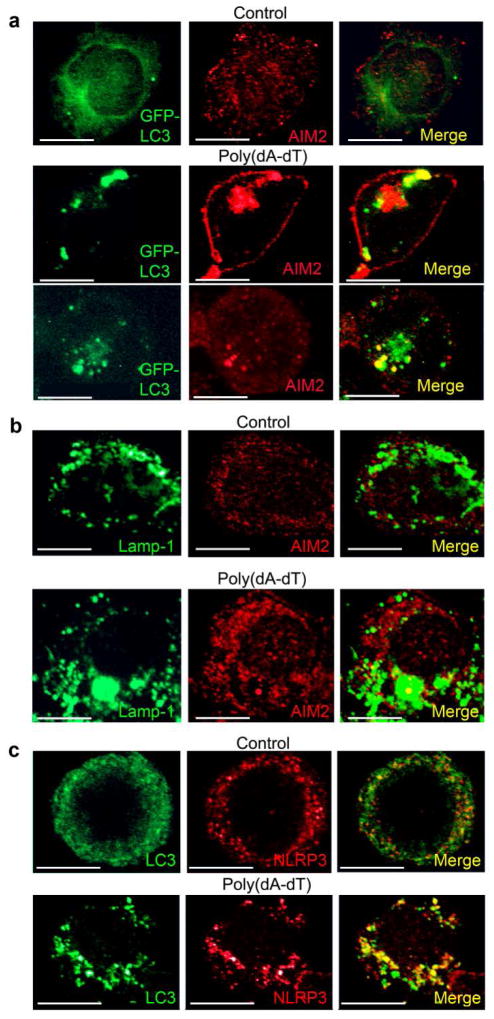

We also verified that the intracellular sensors AIM2 and NLRP3 would partially localize with the autophagosomes by showing that intracellular structures delineated by GFP-LC3 or an antibody to Lamp-1 co-localized with AIM2 after poly(dA-dT) transfection (Fig. 3a, b) and that immunostained endogenous NLRP3 and LC3 overlapped in THP-1 cells following exposure to LPS and ATP (Fig. 3c). Together these results indicate that both AIM2 and NLPR3 inflammasomes can be engulfed by autophagosomes and likely destroyed by merging with Lamp-1 positive lysosomes.

Figure 3.

The inflammasome sensor partial co-localizes with autophagosomes following inflammasome activation. (a) Confocal microscopy of differentiated GFP-LC3 expressing THP1 cells transfected with 1.5 μg/ml poly(dA-dT) for 2h, and then immunostained for endogenous AIM2. (b) Confocal microscopy of differentiated THP-1 cells transfected with poly(dA-dT) for 3h prior and immunostained for Lamp-1 and AIM2. (c) Confocal microscopy of differentiated THP-1 cells treated with LPS (500 ng/ml) and ATP (3mM) for 2 hrs, or not, prior to immunostaining for endogenous LC3 and NLRP3. Scale bars shown are 10 μm. Each experiment repeated a minimum of three times.

Manipulation of autophagy regulates inflammasome activation

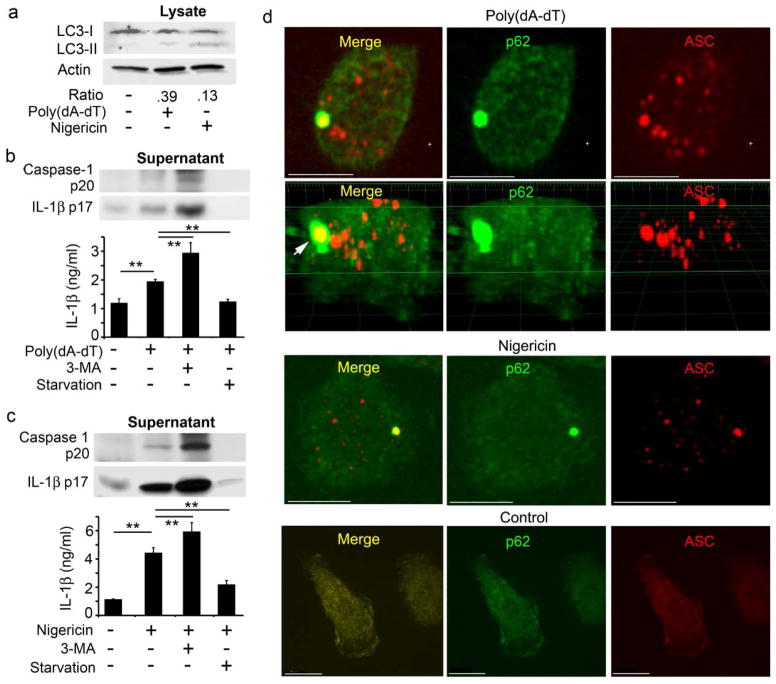

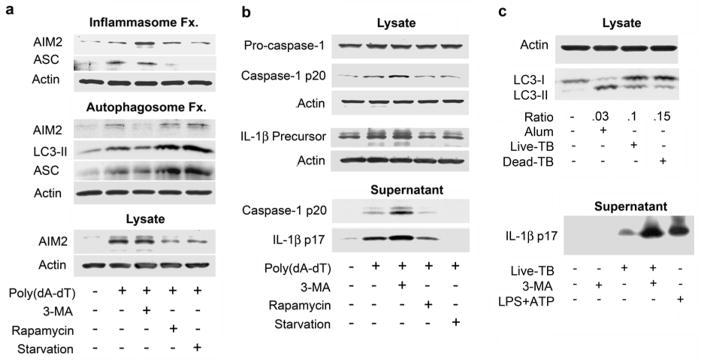

Next, we examined AIM2 inflammasome activity in conditions in which we blocked autophagy using the PI3K inhibitor 3-MA or enhanced autophagy by either amino acid deprivation or rapamycin treatment. Both amino acid starvation and rapamycin trigger autophagy by inhibiting the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)33. Following AIM2 inflammasomes activation by poly(dA-dT) stimulation in differentiated THP-1 cells, we used AIM2 immunoblotting to detect the AIM2 distribution between cell fractions enriched for inflammasomes or for autophagosomes, as compared to total cell lysates. Transfection of poly(dA-dT) induced a modest increase of AIM2 in both fractions and an increase in the total cell lysates (Fig. 4a). Blocking autophagy with 3-MA increased the amount of AIM2 in the inflammasome fraction and reduced it to the basal level in the autophagosome fraction (Fig. 4a). This suggests that the autophagosome fraction is not contaminated with inflamasomes and that, by blocking autophagy, the amount of AIM2 associated with inflammasomes is increased. Amino acid starvation and rapamycin treatment reduced the amount of AIM2 in the cell lysates without altering the amounts in the two fractions. However, these autophagy stimuli increased the levels of LC3-II and ASC in the autophagosome fractions (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4.

Manipulating autophagy affects inflammasomes. (a) Comparison of cell lysates from differentiated THP-1 cells, transfected or nor, with 1.5 μg/ml poly(dA-dT), treated or not with the indicated reagents, separated into an inflammasome enriched fraction (top) or an autophagosome enriched fraction (middle). Those fractions along with the total cell lysates (bottom) were immunoblotted for the indicated proteins. (b) Comparison of cell lysates and cell supernatants prepared from differentiated THP-1 cells, transfected or not, with poly(dA-dT) and immunoblotted for the indicated proteins. (c) Analysis of cell lysates and supernatants from mouse BMDMs primed with LPS (20 ng/ml) and treated with Alum, exposed to live M. tuberculosis or dead M. tuberculosis for 5h for LC3 expression IL-1β production. To detect IL-1β primed mouse BMDMs were infected with live TB overnight in the presence or absence of 3-MA (2mM). LPS+ATP treatment served as a positive control. Cell supernatants were collected and IL-1β levels immunoblotted. All experiments were repeated at least twice.

Next, we measured the levels of mature IL-1β and activated caspase-1 in the cell lysates and cell culture supernatants of differentiated THP-1 cells transfected with poly(dA-dT) and treated with 3-MA, rapamycin or subjected to amino acid starvation. Transfection of poly(dA-dT) increased the amounts of IL-1β precursor and activated caspase-1 in the cell lysate and the amount of activated caspase-1 and mature IL-1β in the cell supernatant (Fig. 4b). Consistent with the AIM2 fractionation data, blocking autophagy by 3-MA increased inflammasome activity, as reflected by increased IL-1β and activated caspase-1 in the lysate and cell supernatant compared to controls (Fig. 4b). Augmenting autophagy by either starvation or rapamycin treatment decreased inflammasome activity, as reflected by the decline in IL-1β and activated caspase-1 in the lysate and cell supernatant compared to the control (Fig. 4b). These results indicate that pharmacologic augmentation or inhibition of autophagy can regulate AIM2 inflammasome activity. In addition, the pharmacologic manipulation of autophagy affected the amount of IL-1β in the cell supernatant of differentiated THP-1 cells stimulated with the NLRP3 inflammasome inducers uric acid crystals or nigericin, although this effect was more evident with nigericin (supplement Fig. 3).

To test whether autophagy may affect inflammasome activation during a bacterial infection of normal macrophages, we examined the effect of autophagy blockade on IL-1β production following the infection of mouse macrophages with M. tuberculosis. A complex interplay between autophagy and inflammasome activation likely occurs during M. tuberculosis infection. Autophagy inhibits M. tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages and inflammasome activation contributes to bacterial clearance by promoting phagolysosomal maturation34. However, M. tuberculosis actively suppresses inflammasome activation by virtue of its gene product Zmp135. M. tuberculosis infection of mouse BMDM induced autophagy, as indicated by LC3 cleavage (Fig. 4c). Alum, a known inducer of autophagy, was used as a positive control. Inhibition of autophagosome formation by 3-MA treatment in M. tuberculosis infected cells lead to an increase in IL-1β production in the supernatant (Fig 4c). There results suggest that a variety of stimuli that induce inflammasomes, including exposure to M. tuberculosis, also trigger autophagy, which limits early IL-1β production.

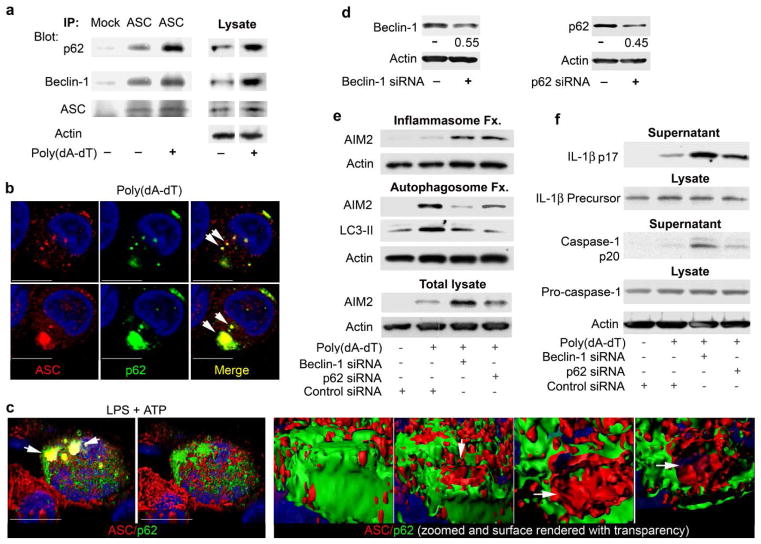

Connecting the inflammasome and autophagy pathways

The autophagic adaptor p62 links ubiquitinated substrates to the autophagy pathway13,14. To test if components of the inflammasome undergo ubiquitination we checked whether p62 associated with ASC. In differentiated THP-1 cells, some p62 and Beclin-1 co-immunoprecipitated with ASC even in the absence of induced inflammasome activity. This suggested that low levels of autophagy may keep inadvertent inflammasome activity in-check. The induction of inflammasomes by the transfection of poly(dA-dT) in THP-1 cells increased the amount of p62 that co-immunoprecipitated with ASC (Fig. 5a). Immunostaining for ASC and p62 in control or poly(dA-dT) transfected differentiated THP-1 cells showed that in the absence of inflammasome activation p62 resided predominantly in the cytosol with occasional small p62 dots, while ASC exhibited a granular cytoplasmic expression pattern with some enrichment near the cell cortex (data not shown). Transfection of poly(dA-dT) induced small and large cytoplasmic ASC aggregates, which occasionally co-localized with p62 (Fig. 5b). Similarly, p62 and AIM2 partially co-localized in stimulated cells and AIM2 immunoprecipitates contained p62, ASC, and Beclin-1 (Supplementary Fig. 4). NLRP3 inflammasomes induction by stimulating differentiated THP-1 cells with LPS and ATP induced an intimate association between p62 and ASC, as three dimensional reconstruction with surface rendering showed many of the ASC aggregates studded with p62 (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Video 2).

Figure 5.

Beclin-1 and p62 are linked to inflammasome regulation (a) ASC immunoprecipitates from differentiated THP-1 cells transfected with 1.5 μg/ml poly(dA-dT) for 2 h, or not, were immunoblotted for Beclin-1 and ASC, stripped and re-immunoblotted for p62. (b) Confocal microscopy of similarly treated differentiated THP-1 cells immunostained for p62 (green) and ASC (red). Arrows indicate co-localized proteins. (c) Confocal microscopy of differentiated THP-1 cells treated with LPS (500 ng/ml) and ATP (3mM) for 2h, immunostained for p62 (green) and ASC (red). The left two images show a merged channel volume and surface rendering of a 3D reconstruction. The four right images show co-localization in a zoomed structure. Part of the signal was removed to uncover red (ASC) signal inside green (p62) stained area (arrows). (d) Immunoblotting of cell lysates from cells twice transfected with scrambled, Beclin-1, or p62 siRNAs for the indicated proteins. The ratio of targeted to control expression is shown. (e) Comparison of inflammasome and autophagosome fractions to total cell lysates from differentiated THP-1 cells transfected with scrambled, Beclin-1, or p62 siRNAs X2. The second transfection contained poly(dA-dT). The cell lysates prepared 4h after the last transfection were fractionated or not and immunoblotted for the indicated proteins. (f) Immunoblotting of supernatants and cell lysates from differentiated THP-1 cells treated as in part e. Supernatants were collected from cells cultured 6h in serum free media. Scale bars shown are 10 μm. All experiments were performed at least twice.

To further test p62 involvement in the regulation AIM2 inflammasomes, we reduced Beclin-1 or p62 expression in differentiated THP-1 cells and examined the partitioning of AIM2 protein expression between inflammasome and autophagy fractions. The siRNAs reduced Beclin-1 or p62 expression levels approximately 50% consistent with the transfection efficiency of 40–50% (Fig. 5d). The autophagy fraction contained LC3-II, but scant amount of LC3-I (note band above prominent LC-II band). Reducing either Beclin-1 or p62 protein expression increased AIM2 in the inflammasome fraction, and reduced it in the autophagosome fraction (Fig. 5e). Finally, reducing Beclin-1 or p62 expression enhanced the amount of mature IL-1β and active caspase -1 in the cell supernatants following activation of AIM2 inflammasomes in THP-1 cells (Fig. 5f). These experiments indicate that inflammasomes recruit the autophagic adapter protein p62, which helps deliver inflammasomes to autophagosomes.

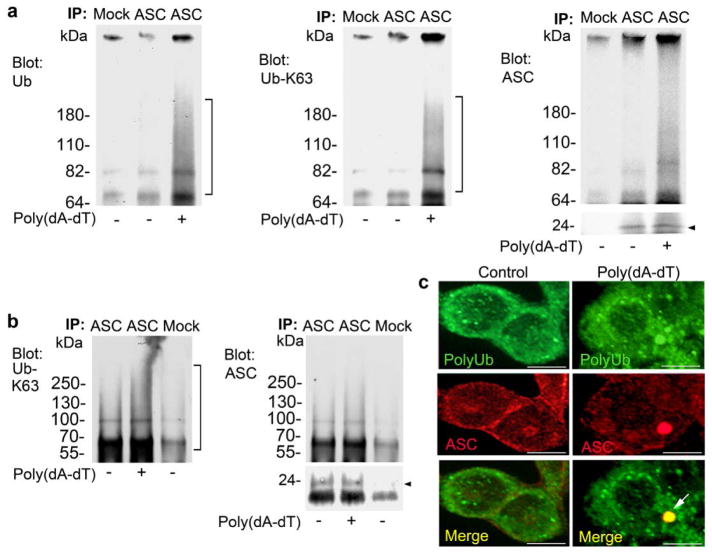

Inflammasomes undergo K63 linked polyubiquitination

The co-immunoprecipation of p62 with ASC as well as their co-localization suggested that either ASC or an ASC associated protein is ubiquitinated following induction of AIM2 inflammasomes. To check that these modifications provided targets for the ubiquitin binding domain of p62, we immunoblotted for ubiquitin in ASC immunoprecipitated from lysates of differentiated THP-1 transfected cells with poly(dA-dT). In the absence of poly(dA-dT) stimulation, very low amounts of ubiquinated proteins co-immunoprecipitated with ASC, however, after poly(dA-dT) transfection, we detected a prominent smear of ubiquinated proteins. The ubiquitin binding domain of p62 has a preference for K63-linked polyubiquitin chains12. Stripping and re-blotting the ASC immunoprecipitations for K63-linked ubiquitin revealed a prominent smear of ubiquitinated proteins, while repeating this procedure with the ASC antibody indicated that ASC itself likely undergoes K63-linked ubiquitination (Fig. 6a). Repeating this experiment by dissociating the proteins in the lysates prior to the immunoprecipitation further substantiated ASC ubiquitination (Fig. 6b). Finally, we transfected differentiated THP-1 cells with poly(dA-dT) and immunostained the cells for polyubiquitin chains and ASC. Large ASC aggregates co-localized with polyubiquitin (Fig. 6c). These results indicate that ASC aggregates are polyubiquitinated and suggest that these inflammasome aggregates can be targeted by p62 into the autophagy pathway.

Figure 6.

Induction of the AIM2 inflammasome triggers polyubiquitination of ASC. (a) ASC immunoprecipitates from differentiated THP1 cells transfected with 1.5 μg/ml poly(dA-dT) for 2h were immunoblotted for ubiquitin, stripped, re-blotted for K63-linked ubiquitin, stripped, and re-blotted for ASC. Experiment performed three times. (b) ASC immunoprecipitates from differentiated THP1 cells treated as above were prepared using a lysis buffer containing 1% (v/v) SDS, and heated for 95°C for 5 minutes to dissociate the proteins. The samples were diluted and ASC immunoprecipitated (24 kDa). The indicated proteins were immunoblotted. Experiment performed twice. (c) Confocal microscopy of differentiated THP-1 cells transfected with poly(dA-dT) for 2h immunostained for ASC (red) and polyubiquitin (green). Scale bars shown are 10 μm.

Autophagy affects inflammasome activity in primary human cells

Next we tested if autophagy regulates inflammasome activity in primary human monocyte or macrophages. In elutriated human monocytes stimulated with nigericin or transfected with poly(dA-dT) to activate the inflammasome, autophagy was enhanced by amino acid starving or inhibited by 3-MA treatment. The levels of inflammasome activity were monitored by measuring IL-1β and caspase 1 p20 levels in the cell supernatants, while the induction of autophagy was verified by LC3 immunoblotting. Although the transfection efficiency of poly(dA-dT) into primary monocytes or macrophages was low, a small decrease in the ratio between LC3-I and LC3-II was noted, while nigericin potently induced LC3 processing (Fig. 7a). Both poly(dA-dT) exposure and nigericin triggered an increase in IL-1β production in human monocytes or macrophages that could be modulated by either amino acid starvation or the addition of 3-MA (Fig. 7b & c). In addition, similar to the experiments with THP-1 cells, treatment of the human cells with poly(dA-dT) or nigericin resulted in a partial co-localization between ASC and p62 (Fig. 7d). These results indicate that similar to murine macrophages and differentiated THP-1 cells that inflammasome activation in human monocytes/macrophages can be modulated by the level of autophagy.

Figure 7.

Inflammasome activity in primary human monocytes/macrophages can be modulated by autophagy. (a) Immunoblot of cell lysates prepared from human monocytes/macrophages prime with LPS (10 ng) and subsequently transfected with 1.5 μg/ml poly(dA-dT) or treated with nigericin (4 μM) for 6 hrs. The ratio shown is the induced LC3-I/LC3-II ratio divided by the basal LC3-I/LC3-II ratio. (b) Analysis of supernatants from monocytes/macrophages treated as indicated for 6h for IL-1β. Supernatants were immunoblotted or assayed for IL-1β by ELISA, p values < 0.01 (**). (c) Similar experiment as part b except nigericin was used to stimulate inflammasome activation. (d) Confocal microscopy of LPS primed human monocyte/macrophages transfected with poly(dA-dT) for 3 hours, treated with nigericin for 3h, or non-stimulated immunostained for p62 (green) and ASC (red). Arrows indicate the co-localized proteins. The second panel from the top is a 3D volume rendering reconstructed from confocal z-stack images showing p62 (green) and ASC structures (red). Scale bars shown are 10 μm. All experiments performed at least twice.

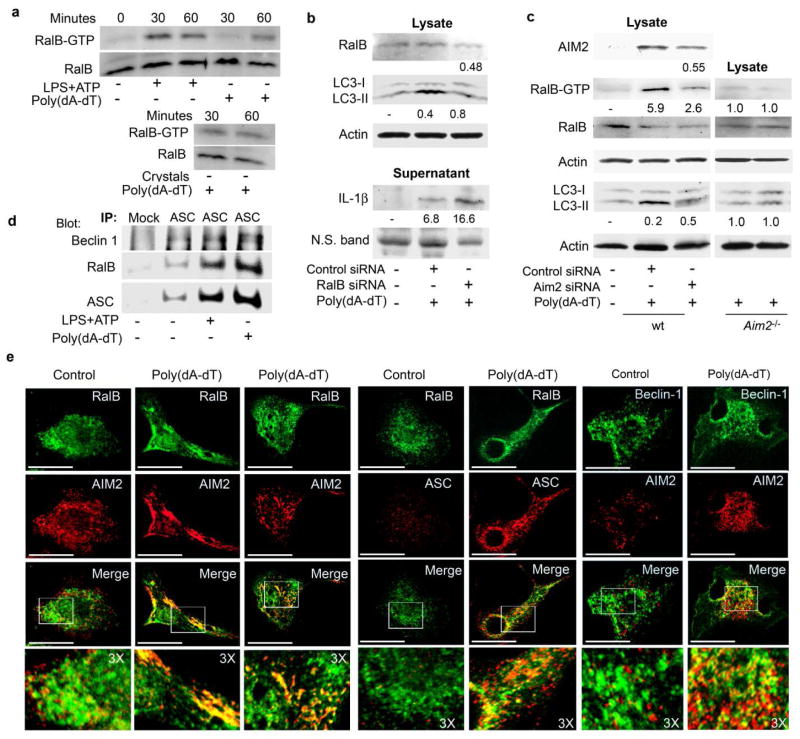

Inflammasome activation induces RalB nucleotide exchange

Nutritional deprivation triggers RalB nucleotide exchange leading to the binding of GTP-RalB to Exo84, which serves as a platform to assemble protein complexes required for isolation membrane formation and maturation6. To determine whether signals that trigger inflammasome activation affected RalB nucleotide exchange, we used a RalBP1 pull down assay to detect GTP-RalB in cell lysates from mouse BMDM treated with LPS+ATP, uric acid crystals, or transfected them with poly(dA-dT). We found that all three signals rapidly induced RalB activation (Fig. 8a). Reducing RalB expression in BMDM using RalB siRNAs impaired the induction of autophagy by poly(dA-dT) and increased IL-1β in the cell supernatant (Fig. 8b). Reducing AIM2 expression using siRNAs in BMDM treated with poly(dA-dT) decreased RalB activation and inhibited the induction of autophagy. Furthermore, poly(dA-dT) failed to induce RalB activation in BMDM derived from Aim2−/− mice (Fig. 8c). Immunoprecipitated ASC revealed low constitutive interaction between ASC and Beclin-1 as well as between ASC and RalB. Stimulation with LPS + ATP or transfection of poly(dA-dT) increased the amount of RalB and Beclin-1 in the ASC immunoprecipitate (Fig. 8d).

Figure 8.

Involvement of RalB in inflammasome triggered autophagy. (a) Immunoblot of GTP-bound RalB collected by RALBP1-agarose affinity purification from cell lysates from LPS primed (20 ng/ml) mouse BMDMs exposed to LPS (500 ng/ml) and ATP (3 μM),1.5 μg/ml poly(dA-dT), or uric acid crystals (50 μg/ml). Immunoblotting visualized RalB-GTP in the pull downs and RalB in cell lysates. (b) Immunoblot of lysates and supernatants prepared from mouse BMDM transfected with RalB or control siRNA on 2 sequential days, primed with LPS and exposed to 1.5 μg/ml poly(dA-dT) for 6 h for RalB, LC3, actin, and IL-1β expression. To collect cell supernatants the cells were cultured overnight in serum free media. (c) Immunoblot of cell lysates from mouse BMDMs transfected with AIM2 or control siRNA on 2 sequential days, primed with LPS and 2h later exposed for 1h to poly(dA-dT) for the indicated proteins. A similar experiment using Aim2−/− BMDMs is shown. (d) ASC immunoprecipitates from LPS primed mouse BMDM transfected with poly(dA-dT) for 1h, treated with LPS+ATP for 30 minutes, or non-stimulated immunoblotted as indicated. (e) Confocal microscopy of LPS primed mouse BMDMs transfected with poly(dA-dT) for 30 minutes were immunostained for RalB and AIM2 (first three panels); RalB and ASC (4th and 5th panels); and AIM2 and Beclin-1 (6th and 7th panel). Areas subjected to 3X electronic zoom are outlined by white squares. Scale bars shown are 10 μm. All experiments performed at least twice.

Using confocal microscopy to examine the localization of RalB and AIM2 in BMDM, we found that prior to poly(dA-dT) exposure, RalB and AIM2 exhibited diffuse speckled patterns in the cytosol that poorly co-localized. Thirty minutes after poly(dA-dT) exposure both proteins accumulated in the cytosol with a pronounced overlap in their distribution (Fig. 8e). Transfection of poly(dA-dT) into mouse BMDM also enhanced the co-localization of RalB with ASC, AIM2 with Beclin-1, and Exo84 with AIM2 (Fig. 8e and Supplementary Fig. 5). Treatment of mouse BMDM with uric acid crystals resulted in overlap of ASC and Beclin-1 in the neighborhood or the crystals as well as the partial co-localization of ASC with Exo84 (Supplementary Fig. 5). Finally, transfection of poly(dA-dT) or treatment with LPS+ ATP in differentiated THP-1 cells caused a redistribution of RalB and ASC resulting in considerable overlap in their expression within the stimulated cells (Supplementary Fig. 6). These experiments indicate that both starvation-induced autophagy and inflammasome-induced autophagy trigger RalB nucleotide exchange and that within cells inflammasome components partially co-localize s with Beclin-1, Exo84, and RalB.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that the activation of inflammasomes lead to an induction of autophagy, which acted to limit inflammasome activity by physical engulfment. Stimulation of inflammasomes lead to autophagosome formation, which was initially independent of ASC, caspase-1, or IL-1βproduction. Pharmacological manipulation of autophagy modulated the production of IL-1β. Autophagy was able to capture and degrade inflammasomes via inflammasome ubiquitination, which lead to the recruitment of p62 and LC3. Autophagosome formation in the context of inflammasome induction was functionally important, as reducing p62 expression or autophagy blockade enhanced IL-1β production. Signals that induce inflammasome activation rapidly lead to RalB nucleotide exchange, a known direct trigger of autophagosome formation. Furthermore, reducing RalB expression decreased inflammasome-triggered autophagy and augmented IL-1β production. These data suggest an intimate relationship between inflammasome activation and autophagosome nucleation.

Although we have established a role for autophagy in downregulating inflammasome activity, the relationship between inflammasomes and autophagy may be complex and dependent upon the specific set of signals that trigger the two pathways and the particular cell type15. For example, the infection of macrophages with Shigella provides a complicated set of stimuli that triggers autophagy and inflammasome activation36. Shigella enters epithelial cells by phagocytosis and penetrates the cytosol by breaking the vacuolar membrane. These membrane remnants recruit LC3 and p62, undergo polyubiquitination, and clearance by autophagy37. Inflammasome components are localized on these membranes and their removal correlates with a dampened inflammatory response. The removal of the vacuolar membranes by autophagy is reminiscent of the removal of inflammasomes observed in this study. Autophagosomes can also suppress inflammasome activity by reducing the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)38. Autophagy blockade was shown to lead to the accumulation of damaged, ROS-generating mitochondria, which activated NLRP3 inflammasomes. Conversely, suppressing mitochondrial activity reduced ROS generation and inhibited NLRP3 inflammasome activation39. Although the majority of our experiments used model ligands, which represent much less complicated stimuli than intracellular bacteria or virus, our assays suggest that the exposure of macrophages to stimuli that activate inflammasomes rapidly induces autophagy. In a more physiologically relevant model, we used exposure of bone marrow derived mouse macrophages to M. tuberculosis. Despite the known ability of M. tuberculosis to suppress IL-1β production35, the blockage of autophagy markedly enhanced IL-1β production following infection.

Our study raises several questions. How do signals that trigger inflammasome activation upregulate autophagy and what is the connection between the biochemical mechanisms that drive inflammasome assembly and trigger autophagosome nucleation? We showed that autophagy induction is dependent upon the inflammasome sensor, but not ASC or caspase-1. Furthermore, stimuli that trigger inflammasomes cause RalB nucleotide exchange. RalB-GTP is known to trigger the assembly of Exo84-Beclin-1 and Exo84-Vps34 complexes leading to autophagy induction6. We observed that RalB also partially co-localizes with AIM2 and ASC following the triggering of inflammasomes. It remains unclear how nutrient starvation and inflammasome activation leads to RalB nucleotide exchange, but it is presumably mediated by one of the five known RalB guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs)6. It is interesting to speculate that the exocyst, a hetero-octameric complex, which has been implicated in signaling during pathogen infection and in the assembly of the autophagosome machinery, may also have some direct involvement in the assembly and targeting of inflammasomes.

The induction of RalB nucleotide exchange provides a mechanism by which stimulation of inflammasomes can trigger autophagosome assembly, but it does not explain why inflammasomes are autophagosome targets. Our finding that the activation of inflammasomes leads to the ubiquitination of ASC and perhaps other inflammasome components provides a potential answer. The ubiquitinated inflammasome can recruit p62, which by virtue of its LC3 binding domain can deliver the inflammasome to the autophagy pathway. Although inflammasome mediated IL-1β production was not necessary for the induction of autophagy over the time-frame we examined, it may contribute over a longer time frame.

Another question is which ubiquitin E3 ligase ubiquitinates ASC. TRAF6 is an interesting candidate. TRAF6 directly associates with p62, which triggers the K63-linked ubiquitination of TRAF6 increasing its E3 ligase activity40,41. Beclin-1 serves as a TRAF6 substrate and its ubiquitination by TRAF6 facilitates the induction of autophagy26. TRAF6 is also known to be recruited to the vacuolar membrane remnants during Shigella infection of epithelial cells36. While the vacuolar membrane remnants predominantly undergo K48-linked ubiquitination for which p62 may have less affinity, K48-linked ubiquitin may serve as a localizing factor, since K48R ubiquitin overexpression blocked the co-distribution of p62 and polyubiquitinated proteins on membrane remnants36. Similarly, since both AIM2 and ASC lack a TRAF6 consensus binding site42 perhaps a component of the inflammasome initially undergoes K48-linked ubiquitination, which recruits the p62-TRAF6 complex. Alternatively, another E3 ligase ubiquitinates ASC.

Finally, why does autophagy fail as a negative-feedback loop in diseases characterized by excessive production of IL-1β? The simultaneous activation of inflammasomes and autophagosomes assembly acts to limit inflammasome activity and in the setting of a limited insult allows the cells to return to a basal state by the eventual elimination of inflammasomes. However, in the setting of persistent inflammatory stimuli autophagy presumably only tempers inflammasome activity. We would predict that autophagosome blockade in the setting of chronic inflammation would severely worsen the inflammatory response. Some inflammatory signals or infections can trigger pyroptosis, a highly inflammatory form of cell death in which cells lose their membrane integrity and secrete large amounts of inflammatory cytokines36. Some evidence exists that autophagy may negatively regulate pyroptosis43. By eliminating the ASC pyroptosome, autophagy could serve as cell survival mechanism when the infection is not overwhelming.

We conclude that the induction of inflammasomes is accompanied by autophagosome formation. Autophagy can limit inflammasome activity and potentially help rid cells of ASC pyroptosomes. The ubiquitination of these structures, the recruitment of p62 and LC3 serve to link inflamasomes and pyroptosomes to the autophagy pathway. The failure to appropriately clear inflammasomes and ASC pyroptosomes will likely lead to excessive inflammation and cell death. The pharmacologic manipulation of autophagy may provide a potent means to modify inflammatory responses.

SUPPLEMENTARY METHODS

Mouse cells, cell culture, plasmids, and reagents

Wild type C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory or Taconic Farm. The Asc −/− (Pycard−/−) mice were originally generated at Millennium Pharmaceuticals as described30. The Casp1−/− mice were originally generated by Dr. Richard Flavell as described44 and subsequently backcrossed on to C57BL/6 (N10). The Aim2−/− mice have been described21. All mice used in this study were 6 to 12 wk of age. Mice were housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions. All the animal experiments and protocols used in the study were approved by the NIAID Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) at the National Institutes of Health. To prepare bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) bone marrow was flushed from femurs and tibia of mice and plated in 30% L929 cell-conditioned medium diluted in complete RPMI. Fresh medium was added on day 4 and macrophages were used after 6–8 days of culture. THP-1 cells were obtained from the ATCC and were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. THP-1 cells were differentiated into macrophages by treating them for three hours with 50 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, Sigma-Aldrich). Human peripheral blood monocytes were obtained from healthy volunteers by leukapheresis and prepared by countercurrent centrifugal elutriation. The LC3 complementary DNA (cDNA) was a gift from Dr. N. Mizushima (Tokyo Medical and Dental University). GFP-LC3 was used to generate a stable THP-1 cells expressing the marker. Poly(dA-dT) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and was used to treat differentiated THP-1 cells (1–2 μg/ml) and primary macrophages. It was prepared with HD Transfection Reagent following the manufacture’s recommendation (Roche). For the confocal imaging, poly(dA-dT) was labeled with Label IT Tracker-Cy3 (Mirus) following the manufacture’s protocol. Rapamycin (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at 25 nM, Z-VAD-FMK (Sigma-Aldrich) at 10 μM, and 3-methyladenine (3-MA, Sigma-Aldrich) at 5 mM. IL-1β neutralizing antibodies (R&D Systems) were used at a final concentration of 1μg/ml. LPS (Alexis) and ATP (Sigma-Aldrich) used to stimulate differentiated THP-1 cells were used at a concentration of 500 ng/ml and 2 mM, respectively. Nigericin (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at a concentration of 4 μM and uric acid crystals (Alexis) was used at a concentration of 50 μg/ml.

RNA interference

siRNA pools targeting human or mouse AIM2, human Beclin-1, human p62, mouse RalB, or scrambled control were purchased (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The siRNAs were used at concentration of 40 nM and were prepared with 2 μl of HD Transfection Reagent. The siRNAs were used to treat differentiated THP-1 overnight or mouse BMDM. A day later the same siRNAs were mixed with poly(dA-dT). The cells were analyzed from 1–8 hours after inflammasome activation as indicated.

GFP-LC3 assay

The assays were performed as detailed previously8. A minimum of 50 to 100 GFP-positive cells per sample were counted and the number of cell with GFP-LC3 dots were enumerated. Cells were scored as positive if they had more than three large GFP-LC3 dots. The data were presented as a percentage of the total number of GFP-positive cells visualized.

Immunoblot analysis and immunoprecipitations

Antibodies against ubiquitin (P4D1, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-p62 (clone 3, BD Transduction Laboratories), mouse anti-Beclin-1 (612113, BD Transduction Laboratories), K63-linked polyubiquitin chains (HWA4C) (eBiosciences), mouse anti-AIM2 (SAB1406827, Sigma Aldrich), mouse anti-RalB (clone 25, Millipore), rabbit anti-ASC (AL177 Alexis Biochemicals), goat anti-IL-1β (AB-401-NA, R&D Systems), rabbit anti-Capase-1 (EPR4321, Epitomics), mouse anti-LC3 (4E12, MBL International), and Actin (Sigma Aldrich) were used for immunoblotting their respective proteins as described8,26. To strip a membrane it was submerged in a buffer that contained 100 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS, 62.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.7) at 55 to 60°C for 60 min with agitation and then washed 6 times. Immunoblots were scanned and imported into Photoshop as unmodified TIFF files. Polyclonal rabbit antibodies against ASC and protein G plus-agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used for immunoprecipitation of poly(dA-dT) activated inflammasomes. The cells were lysed in a buffer that contained 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 0.5 % Triton X-100, 0.5 % CHAPS, and 10% glycerol with a protease inhibitor cocktail tablet. The lysates were incubated with the appropriate antibodies for 2 hours at 4°C, at which point Protein G PLUS-Agarose was added and incubated for 1 hour at 4°C. The immunoprecipitates were collected, washed eight times with lysis buffer, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. To check ubiquitination following denaturation of the cell lysates we followed a standard protocol45. To prepare inflammasome and autophagosome enriched fractions we also followed previously published methods46,47.

Measurement of activated caspase-1 and mature IL-1β

Cells cultured in 12 well plates were washed twice with OPTI-MEM medium and 0.5 ml OPTI-MEM medium was added to each well along with the indicated reagents and the cells were cultured for 6 hours. To amino acid and serum starve the cells they were washed with PBS twice and cultured in Earle’s balanced salts solution (EBSS) at 37°C for 6 hours. The medium collected from each well was mixed with 0.5 ml methanol and 0.125 ml chloroform, vortexed, and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 5 minutes. The upper phase from each sample was removed and 0.5 ml methanol added. The samples were centrifuged again for 5 minutes at 13,000 rpm, the supernatant removed, and the pellet dried for 5 minutes at 50 °C. 60 μl of loading buffer was added to each sample followed by boiling for 10 minutes prior to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antibodies to detect activated caspase-1 (Cell Signaling) or mature IL-1β (Cell Signaling). The adherent cells from each well were lysed with the above mentioned lysis buffer and immunoblotted to determine the cellular content of the different proteins.

Immunofluorescence

For confocal imaging of fixed cells mouse BMDM, human differentiated monocytes, or differentiated THP-1 cells were used. Following the appropriate treatment the cells were washed twice with PBS, fixed with cold methanol overnight at −20 °C, and washed again with PBS. The cells were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma-Aldrich) for 1h. Rabbit anti-ASC (sc-22514-R, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-p62 (clone 3, BD Transduction Laboratories), anti-multi-ubiquitin-FK2 (MBL International), rabbit anti-AIM2 (sc-137967, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-RalB (clone 25, Millipore), rabbit anti-LC3 (Sigma), mouse mAb anti-NLRP3 (Enzo Life Sciences) or anti-Lamp-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies were used to immunostain the cells. Goat anti-mouse, goat anti-rabbit, and rabbit anti-goat Alexa 488 or Alexa 568 conjugated antibodies (Molecular Probes) were used as secondary antibodies. Two systems were used for cell imaging. A PerkinElmer Ultraview spinning wheel confocal system mounted on Zeiss Axiovert 200 equipped with an argon/krypton laser. Images were collected using a 100X Plan-Aprochromax oil immersion objective (NA 1.4). A Leica TCS-SP5 X supercontinuum confocal microscope equipped with an argon/white laser (Leica Microsystems, Exton, PA), and 63X oil immersion was maintained at objective (NA 1.4) was also used for imaging. For live cell studies the CO25% and the temperature at 37°C. Images of dynamic cell interactions were recorded as vertical z-stacks (3D) or as vertical z-stacks over time (4D). Scale bars shown are 10 μm. Imaris 7.1.1 (Bitplane AG), Ultraview 5.5 (PerkinElmer) and Adobe Photoshop 7 (Adobe Systems) were used for the image processing.

Electron microscopy

Cell were pelleted in 1.5% low melting point agarose, washed with PBS (3X), dehydrated in ethanol series, and embedded in LR White (SPI). Ultrathin sections were mounted on 150-mesh uncoated nickel grids. Grids were floated on blocking solution (PBS, 0.1% Tween 20, 0.5% cold-water fish gelatin (Ted Pella, Inc.) for 20 min, incubated for one hr with ASC antibody, rinsed three times, incubated for 1 hr with 15nm gold-conjugated Protein A (Ted Pella, Inc.), rinsed in PBS, water, and air dried. Sections were stained with aqueous uranyl acetate and examined with a Phillips CM10 electron microscope.

Infection of mouse BMDM with M. tuberculosis

Mouse BMDMs were plated at 1.5×106 cells per well in a 12 well plate, primed for 3 hr with 20 ng/ml LPS, and then stimulated for 5–6 hours with 500 μg/ml of heat-killed H37a, live H37Ra at an MOI of 1, or alum (400 ug/ml). The cells were lysed with the above mentioned lysis buffer with 0.3% SDS (v/v) and protease inhibitors. The prepared lysates were immunoblotted for LC3. For the IL-1β in supernatant the cells were stimulated overnight as above in the presence or absence of 2 mM 3-MA. The cells were induced with LPS+ATP (5 mM) as the positive control. Equal amounts of cell supernatants were precipitated with methanol/chloroform as above and immunoblotted with goat anti-mouse IL-1β antibodies.

RalB activation assay

To detect GTP bound RalB we used a RalB activation kit (Millipore). We modified the manufacture’s protocol slightly. We added 0.3% (v/v) SDS to the lysis buffer supplied by the manufacturer. The stimulated cells were lysed for 1 minute after which the lysates were immediately centrifuged at 14,000 rpm, for 1 minute. The supernatants were collected, diluted 4 folds with the lysis buffer in the absence of SDS, and then the agarose bound with RalBP1 was added. Otherwise we followed the manufacture’s recommendations.

Supplementary Material

Video 1. NLPR3 inflammasomes co-localize with GFP-LC3. Video begins as a 3D volume rendering of NLPR3 inflammasomes co-localizing with autophagosomes. ASC is shown in red and GFP-LC3 in green. The cell is rotated 90 degrees and transfers into surface rendering solid object with green channel (GFP-LC3) shown as transparent. This transparency shows the co-localization of GFP-LC3 with endogenous ASC immunostained structures clearly inside.

Video 2. ASC and p62 co-localization. The movie shows the colocalization between p62 and ASC by 3D volume rendering of both signals. ASC is shown red and p62 shown green. Initial immunostaining is shown after which the imaging data is transferred after rotation into surface rendering and zoomed to one of the immunostained structures. The nucleus signal (blue) is shown as a transparent volume. Part of the solid nontransparent surface model is then clipped off to reveal ASC localization (red) inside p62 stained (green) structures inside of the cell. The larger as well smaller structures in the cell are shown in the movie.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of NIAID, NIH.

The authors would like to thank M. Rust for her editorial assistance and Dr. A. Fauci for his continued support. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health [National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases].

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C-S.S designed and performed the majority of the experiments and helped write the manuscript, K.S. provided mouse macrophages and performed the M. tuberculosis experiments, N-N. H. performed some of the confocal microscopy, J.K. did the image analysis, M.A. did the electron microscopy, K.A.F. provided the Aim2−/− cells and helpful advice, A.S. helped in the design of several experiments and provided helpful advice, and J.H.K. oversaw the experimental design, helped interpret the results, and helped write the manuscript.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Behrends C, Sowa ME, Gygi SP, Harper JW. Network organization of the human autophagy system. Nature. 2010;466:68–76. doi: 10.1038/nature09204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmid D, Pypaert M, Munz C. Antigen-loading compartments for major histocompatibility complex class II molecules continuously receive input from autophagosomes. Immunity. 2007;26:79–92. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deretic V. Autophagy in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:523–528. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levine B, Deretic V. Unveiling the roles of autophagy in innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:767–777. doi: 10.1038/nri2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmid D, Munz C. Innate and adaptive immunity through autophagy. Immunity. 2007;27:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bodemann BO, et al. RalB and the exocyst mediate the cellular starvation response by direct activation of autophagosome assembly. Cell. 2011;144:253–267. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu Y, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 is a sensor for autophagy associated with innate immunity. Immunity. 2007;27:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi CS, Kehrl JH. MyD88 and Trif target Beclin 1 to trigger autophagy in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33175–33182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804478200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delgado MA, Elmaoued RA, Davis AS, Kyei G, Deretic V. Toll-like receptors control autophagy. EMBO J. 2008;27:1110–1121. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akira S, Takeda K, Kaisho T. Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:675–680. doi: 10.1038/90609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trinchieri G, Sher A. Cooperation of Toll-like receptor signals in innate immune defence. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:179–190. doi: 10.1038/nri2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seibenhener ML, et al. Sequestosome 1/p62 is a polyubiquitin chain binding protein involved in ubiquitin proteasome degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8055–8068. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8055-8068.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pankiv S, et al. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24131–24145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ponpuak M, et al. Delivery of cytosolic components by autophagic adaptor protein p62 endows autophagosomes with unique antimicrobial properties. Immunity. 2010;32:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schroder K, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes. Cell. 2010;140:821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernandes-Alnemri T, Yu JW, Datta P, Wu J, Alnemri ES. AIM2 activates the inflammasome and cell death in response to cytoplasmic DNA. Nature. 2009;458:509–513. doi: 10.1038/nature07710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hornung V, et al. AIM2 recognizes cytosolic dsDNA and forms a caspase-1-activating inflammasome with ASC. Nature. 2009;458:514–518. doi: 10.1038/nature07725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burckstummer T, et al. An orthogonal proteomic-genomic screen identifies AIM2 as a cytoplasmic DNA sensor for the inflammasome. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:266–272. doi: 10.1038/ni.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts TL, et al. HIN-200 proteins regulate caspase activation in response to foreign cytoplasmic DNA. Science. 2009;323:1057–1060. doi: 10.1126/science.1169841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. The inflammasomes. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000510. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rathinam VA, et al. The AIM2 inflammasome is essential for host defense against cytosolic bacteria and DNA viruses. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:395–402. doi: 10.1038/ni.1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernandes-Alnemri T, et al. The AIM2 inflammasome is critical for innate immunity to Francisella tularensis. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:385–393. doi: 10.1038/ni.1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saitoh T, et al. Loss of the autophagy protein Atg16L1 enhances endotoxin-induced IL-1beta production. Nature. 2008;456:264–268. doi: 10.1038/nature07383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris J, Hope JC, Lavelle EC. Autophagy and the immune response to TB. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2009;56:248–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1865-1682.2009.01069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kabeya Y, et al. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000;19:5720–5728. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi CS, Kehrl JH. TRAF6 and A20 regulate lysine 63-linked ubiquitination of Beclin-1 to control TLR4-induced autophagy. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra42. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Levine B. Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell. 2010;140:313–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mariathasan S, et al. Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature. 2006;440:228–232. doi: 10.1038/nature04515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinon F, Petrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature. 2006;440:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature04516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sutterwala FS, et al. Critical role for NALP3/CIAS1/Cryopyrin in innate and adaptive immunity through its regulation of caspase-1. Immunity. 2006;24:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto M, et al. ASC is essential for LPS-induced activation of procaspase-1 independently of TLR-associated signal adaptor molecules. Genes Cells. 2004;9:1055–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2004.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li H, et al. Mice deficient in IL-1 beta-converting enzyme are defective in production of mature IL-1 beta and resistant to endotoxic shock. Cell. 1998;80:401–11. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90490-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Mammalian autophagy: core molecular machinery and signaling regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guitierrez MG, et al. Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell. 2004;119:753–768. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Master SS, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis prevents inflammasome activation. Cell Host & Microbe. 2008;3:224–232. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suzuki T, et al. Differential regulation of caspase-1 activation, pyroptosis, and autophagy via Ipaf and ASC in Shigella-infected macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e111. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dupont N, et al. Shigella phagocytic vacuolar membrane remnants participate in the cellular response to pathogen invasion and are regulated by autophagy. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6:137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tschopp J, Schroder K. NLRP3 inflammasome activation: The convergence of multiple signalling pathways on ROS production? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:210–215. doi: 10.1038/nri2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, Tschopp J. A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature. 2011;469:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature09663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanz L, Diaz-Meco MT, Nakano H, Moscat J. The atypical PKC-interacting protein p62 channels NF-kappaB activation by the IL-1-TRAF6 pathway. EMBO J. 2000;19:1576–1586. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.7.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wooten MW, et al. The p62 scaffold regulates nerve growth factor-induced NF-kappaB activation by influencing TRAF6 polyubiquitination. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35625–35629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500237200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ye H, et al. Distinct molecular mechanism for initiating TRAF6 signalling. Nature. 2002;418:443–447. doi: 10.1038/nature00888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bortoluci KR, Medzhitov R. Control of infection by pyroptosis and autophagy: role of TLR and NLR. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:1643–1651. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0335-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuida K, et al. Altered cytokine export and apoptosis in mice de cient in interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme. Science. 1998;267:2000–2003. doi: 10.1126/science.7535475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wertz GE, et al. De-ubiquitination and ubiquitin ligase domains of A20 downregulate NF-κB signaling. Nature. 2004;430:694–699. doi: 10.1038/nature02794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fernandes-Alnemri T, Alnemri ES. Assembly, purification, and assay of the activity of the ASC pyroptosome. Methods Enzymol. 2008;442:251–270. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)01413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gao W, et al. Biochemical isolation and characterization of the tubulovesicular LC3-positive autophagosomal compartment. J Biol Chem. 2009;285:1371–1383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.054197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video 1. NLPR3 inflammasomes co-localize with GFP-LC3. Video begins as a 3D volume rendering of NLPR3 inflammasomes co-localizing with autophagosomes. ASC is shown in red and GFP-LC3 in green. The cell is rotated 90 degrees and transfers into surface rendering solid object with green channel (GFP-LC3) shown as transparent. This transparency shows the co-localization of GFP-LC3 with endogenous ASC immunostained structures clearly inside.

Video 2. ASC and p62 co-localization. The movie shows the colocalization between p62 and ASC by 3D volume rendering of both signals. ASC is shown red and p62 shown green. Initial immunostaining is shown after which the imaging data is transferred after rotation into surface rendering and zoomed to one of the immunostained structures. The nucleus signal (blue) is shown as a transparent volume. Part of the solid nontransparent surface model is then clipped off to reveal ASC localization (red) inside p62 stained (green) structures inside of the cell. The larger as well smaller structures in the cell are shown in the movie.