Abstract

Maize kernels are susceptible to infection by the opportunistic pathogen Aspergillus flavus. Infection results in reduction of grain quality and contamination of kernels with the highly carcinogenic mycotoxin, aflatoxin. To understanding host response to infection by the fungus, transcription of approximately 9000 maize genes were monitored during the host-pathogen interaction with a custom designed Affymetrix GeneChip® DNA array. More than 4000 maize genes were found differentially expressed at a FDR of 0.05. This included the up regulation of defense related genes and signaling pathways. Transcriptional changes also were observed in primary metabolism genes. Starch biosynthetic genes were down regulated during infection, while genes encoding maize hydrolytic enzymes, presumably involved in the degradation of host reserves, were up regulated. These data indicate that infection of the maize kernel by A. flavus induced metabolic changes in the kernel, including the production of a defense response, as well as a disruption in kernel development.

Keywords: Aspergillus flavus, maize, transcription, genetic, aflatoxins, pathogenesis

Introduction

Aspergillus flavus is an opportunistic fungal pathogen that infects developing maize kernels, attacking plants that are weakened by environmental stresses such as drought and heat. Disease reduces grain quality and contaminates the kernel with the carcinogenic mycotoxin aflatoxin (Scheidegger and Payne, 2003; Payne and Yu, 2010; Dolezal et al., 2013; Hruska et al., 2013; Kew, 2013). The development of resistant maize lines has proven difficult although there is evidence for sources of resistance (Brown et al., 1999; Windham and Williams, 2002; Mylroie et al., 2013; Warburton et al., 2013; Mideros et al., 2014). The lack of reliable resistance phenotyping markers, the inconsistency of disease development each year, and an insufficient understanding of host resistance mechanisms, all have made the selection of resistance difficult.

Advances in technology, such as microarrays, have enabled researches the ability to monitor transcription on a genome-wide level and provided a better understanding of how organisms respond to their environment on a cellular level. Studies investigating plant gene expression during pathogen attack have found the defense response goes beyond PR-proteins and involves transcription changes in both primary and secondary plant metabolic pathways and detoxification pathways (Boddu et al., 2007; Doehlemann et al., 2008; Alessandra et al., 2010). Phytohormones like salicyclic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), ethylene (ET) have long been known to be an integral part of the defense response (Glazebrook, 2005; Jones and Dangl, 2006; Robert-Seilaniantz et al., 2011). Yet carbohydrate metabolism pathways, though not typically associated with resistance, may be an important component of the plant defense response including in maize (Berger et al., 2007; Bolton, 2009). Higher maize stalk carbohydrate levels have been associated with increased resistance to stalk infecting fungi, many of which are also capable of infecting the ear and kernel (Dodd, 1980).

Transcriptional changes of maize kernels during infection by A. flavus have been studied using microarrays (Luo et al., 2011; Kelley et al., 2012) and qPCR (Jiang et al., 2011). Kelley et al. (2012) compared maize varieties that were either susceptible or resistant to aflatoxin accumulation. They found 16 genes highly expressed in the resistant variety and 15 in the susceptible variety and concluded that multiple mechanisms are likely involved in resistance to aflatoxin accumulation. Jiang et al. (2011) reported higher levels of gene expression in stress related genes in resistant lines of maize. Luo et al. (2011) found that more maize genes were induced by A. flavus in susceptible kernels compared with resistant kernels. In all these studies, defense-related, and regulatory genes were associated with the response to A. flavus. To provide a clearer understanding of maize kernel resistance to A. flavus we monitored the transcriptional response of maize kernels during infection by A. flavus in the field using a custom DNA microarray. We report changes in expression of well-characterized defense signaling pathways and defense related genes as well as striking changes in expression of genes related to carbohydrate metabolism.

There are several stages in the infection process that host resistance could restrict fungal growth and aflatoxin contamination. Kernel infection with A. flavus begins through silk colonization. Conidia germinate and grow on senescing silks, moving down the silk channel to the developing kernels, which can take as little as 8 days (Marsh and Payne, 1984; Payne et al., 1988b). Subsequent steps in the infection process are less defined, but data suggest that A. flavus can attack kernels during their six stages (Ritchie et al., 1997) of their development: silking (R1), blister (R2), milk (R3), dough (R4), dent (R5), and physiological maturity (R6). Recently, Reese et al. (2011) inoculated detached kernels at stages R2–R5 in the lab and found that kernels at these four stages were susceptible to infection by A. flavus. Fungal infection has been observed in injured kernels as young as the milk (R3) stage (Taubenhaus, 1920; Anderson et al., 1975). These young kernels tend to accrue high concentrations of aflatoxin because of prolonged colonization by the pathogen (Lillehoj et al., 1980; Payne et al., 1988a). Infection in non-injured kernels in the field is thought to take place later, during the dent (R5) developmental stage just prior to physiological maturity (R6) (Koehler, 1942; Marsh and Payne, 1984; Payne et al., 1988a; Smart et al., 1990; Windham and Williams, 1998). Once inside, A. flavus preferentially colonizes the oil-rich germ tissue (Fennell et al., 1973; Jones et al., 1980; Smart et al., 1990; Keller et al., 1994). Fungal growth within endosperm tissue, more specifically the nutrient-rich starchy endosperm, has been observed, but there are discrepancies in the literature as to the extent of colonization (Lillehoj et al., 1976; Smart et al., 1990; Keller et al., 1994; Brown et al., 1995; Dolezal et al., 2013).

Our studies focused on the transcriptional response of developing kernels that were inoculated with A. flavus through a wound. We realize that this approach could overlook some resistance mechanisms, but it results in more consistent disease development. Resistance to infection of wounded kernels is also relevant as it mimics insect injury, which is important in the epidemiology of the disease. Furthermore, to capture the response in the different stages of kernel development, we evaluated A. flavus infection of four kernels stages, R2–R5. We also chose a specific time of 4 days after inoculation to examine gene expression based on previous histological studies by Dolezal et al. (2013) who showed that within 4 days after inoculation A. flavus mycelium reached the aleurone, endosperm, and germ tissue. Thus, sampling at 4 days allowed assessment of host response in several tissue types within the kernels.

Experimental procedure

Fungal strain and culture conditions Aspergillus flavus

NRRL 3357 was grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) at 28°C for 7–10 days. Conidia were dislodge with 0.05% (v/v) Triton X-100 and diluted to a working solution of 1 × 106 spores mL−1.

Maize kernel inoculation and harvesting

Inbred maize genotype B73 was grown at the Central Crops Research Station in Clayton, NC. Ears were hand pollinated and the date recorded on the bag. Ears at the blister (R2), milk (R3), late milk (R3)–early dough (R4), dough (R4), and dent (R5) stages of development were either mock-inoculated or inoculated with A. flavus as outline in Dolezal et al. (2013). Briefly, ears selected for inoculation had the husk pulled back to exposed the developing kernels below. The protruding portion of the pins of the pinbar was dipped into the A. flavus conidial suspension and inserted into the crown of the kernel. The husk was repositioned and secured around the ear with a rubber band, and a paper bag placed over the inoculated ear. Ears inoculated at the blister (R2), milk (R3), dough (R4), and dent (R5) stages of development were removed from the plant 4 days after inoculation (dai), and the kernels flash frozen immediately after removal. Harvested kernels were stored at −80°C until RNA was extracted using the protocol outlined in Smith et al. (2008). Additional ears inoculated at the late milk (R3)–early dough (R4) stage of development were left in the field and picked at end of the growing season. Kernels adjacent to the pinbar-inoculated rows were harvested. Kernels on non-inoculated ears, pollinated the same day as the inoculated ears, were also collected and used as controls. Adjacent diseased kernels and control kernels were cut-in-half and visually compared to assess for physical changes in kernel structure resulting from A. flavus infection.

Microarray processing and analysis

Custom-designed A. flavus Affymetrix GeneChip DNA microarrays were used to identify genes differentially expressed in maize during A. flavus kernel colonization. This multi-species array, in addition to being capable of monitoring genome-wide transcription of A. flavus, has close to 9000 probe sets representing maize genes. This pairing of A. flavus and maize genes onto a single array allowed for simultaneous detection of disease-associated transcript in the plant-pathogen interaction. The majority (83%) of maize genes selected for the array came from seed-specific cDNA libraries. The remaining genes were chosen based on recommendations from members of the maize community and prior association with disease resistance. The quality of RNA extracted from the mock-inoculated and A. flavus-inoculated kernels was assessed before processing. All array work was carried out at the Purdue Genomic Core Facility (http://www.genomics.purdue.edu) in West Lafayette, IN, and standard Affymetrix protocols were followed.

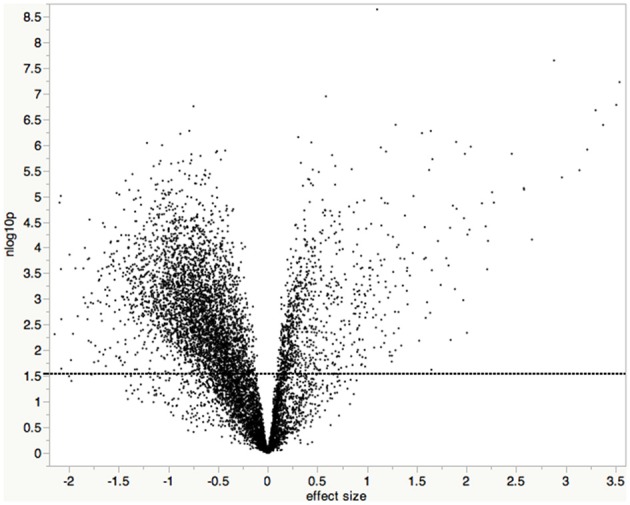

CEL files generated from the GeneChip DNA microarray scans were imported into JMP Genomics and log2 transformed. Mismatched probes were not used in the calculation of the expression values. The expression profiles of A. flavus and maize genes were examined for each array, and arrays for the mock-inoculated treatment that had moderate-to-strong A. flavus signal intensities were removed from further analysis. While these kernels did not visually appear infected, they were likely inadvertently contaminated with A. flavus. Data were then normalized using Loess Normalization. Normalized data from arrays generated from blister (R2), milk (R3), dough (R4), and dent (R5) inoculated kernels stages were grouped into either a mock-inoculated or A. flavus inoculated treatment group. The assemblage of the different developmental stages into a single treatment group allowed for the identification of maize genes that consistently responded to A. flavus infection regardless of what age infection initiated. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed comparing the mock- and A. flavus-inoculated treatment groups. To account for multiple testing, a significance threshold based on a false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.05 was used (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). The data were deposited into Gene Expression Omnibus. The series record number is GSE57629 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE57629). A volcano plot was generated showing significance on the y-axis and fold change on the x-axis using JMP 11 (Figure 1). Gene names were assigned by using Tophat to align the affy probe sequences to the ZmB73_RefGen_v2 reference genome. AgriGO was used to perform Singular Enrichment Analysis (SEA) on differentially expressed genes (Du et al., 2010).

Figure 1.

Volcano plot of test results showing statistical significance vs. fold change. Each point represents the results of one gene, where the x-axis is the difference in expression between A. flavus-infected samples and mock-infected samples (log2 [A. flavus]—log2 [mock]). The y-axis is the –log10 transformed p-value. The dashed line indicates the significance threshold based on an FDR of 0.05 (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995); all points above the line are considered statistically significant.

For SEA, the AGRIGO toolkit was used (http://bioinfo.cau.edu.cn/agriGO/analysis.php). Default values were used for the advanced options including the Yekutieli (FDR under dependency) multi-test adjustment method at a significance level of 0.05.

Validation of microarray data by qRT-PCR

For each of the developmental stages used for the microarray study, a second set of RNA isolations was performed. RNA was treated with DNase (Promega) and cDNA was synthesized using a First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using a SYBR® Green kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The expression levels of a ribosome gene were used for normalization. Data were analyzed by the comparative CT method with the amount of target given by the calibrator 2−ΔΔCT. The primers used for qRT-PCR analysis are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used in qRT-PCR.

| Gene annotation (gene name) | Primers 5′–3′ |

|---|---|

| Structural constituent of ribosome (LOC100285698) | Ribosome F: GGCTTGGCTTAAAGGAAGGT |

| Ribosome R: TCAGTCCAACTTCCAGAATGG | |

| PRms (Pathogenesis related protein, maize seed) (AC205274.3_FG001) | PRms F: TACAATGGAGGCATCCAACA |

| PRms R: CTGTTTTGGGGAGTGAGGTA | |

| β-fructofuranosidase (invertase cell wall1) (GRMZM2G139300) | CWINV1 F: CGGCAAGATCACCCTTAGAA |

| CWINV1 R: CGTAGAGGTGAGCGTCCTTC | |

| 1,4-alpha-glucan branching enzyme (GRMZM2G088753) | SBE F: TAGCCCTGGACTCTGATGCT |

| SBE R: CCGGTTGTTGAAGTTCGTTT | |

| Lipoxygenase4 (GRMZM2G109056) | LOX4 F: ATCGAGATCCTCTCCAAGCA |

| LOX4 R: CTGATCCGCTTCTCGATCTC | |

| Lipoxygenase9 (GRMZM2G017616) | LOX9 F: CCTCATGGCATCAGACTCCT |

| LOX9 R: GAGCTGCACATACGACTCCA |

Results

Differentially expressed genes

Maize kernels were inoculated at the blister (R2), milk (R3), dough (R4), and dent (R5) stages, and harvested 4 days later. Transcriptional changes for 8875 maize genes were monitored with an Affymetrix GeneChip® DNA array. Data were grouped into either mock-inoculated or A. flavus-inoculated treatment groups. An ANOVA comparing mock-inoculated with A. flavus- inoculated treatment groups (α ≤ 0.05 FDR) identified 912 and 3737 of the Affymetrix GeneChip probe-sets up- and down-regulated, respectively, (Table S1). Each probe-set represents a unique maize gene, except for those with a suffix attached to the probe-set name (e.g., ZM_a_at). These probe-sets may contain probes that represent more than one gene within a gene family or contains conserved sequence common to multiple genes. Some maize genes are represented by multiple probe-sets. Consult http://www.affymetrix.com/estore/support/help/faqs/mouse_430/faq_8.jsp for more detail on the different suffixes. This analysis showed the differential expression of genes associated with host resistance and defense signaling pathways, and of genes associated with sugar metabolism.

Gene enrichment analysis (SEA)

To gain additional insight into the collective biological function of proteins whose genes showed differential expression during infection, we performed annotation enrichment using SEA (Du et al., 2010) on the genes listed in Table S1. The resulting list of enriched Gene Ontology terms is shown in Table S2. Notable are transcriptional changes in several genes associated with carbohydrate metabolism. Representative examples include GO:0005975, GO:0006006, GO:0034637, GO:0044262, and GO:0019318.

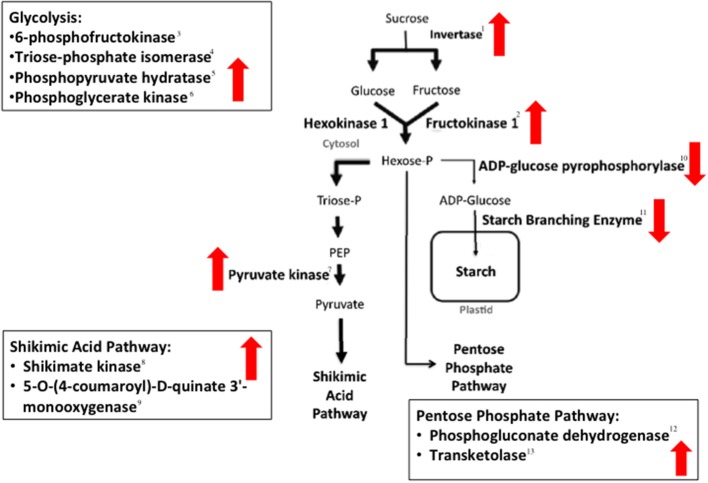

Changes in expression of genes associated with carbohydrate metabolism

Infection of maize kernels with A. flavus resulted in transcriptional changes of several maize genes involved in primary and secondary metabolism, particularly those associated with the synthesis and hydrolysis of starch, and the mobilization of hexoses (Figure 2; Table 2; Table S2). As an example, genes encoding starch biosynthetic enzymes, including two starch branching enzymes, (GRMZM2G088753 and GRMZM2G032628), were down regulated during infection as was ADP-glucose pyrophosphorlase (GRMZM2G429899), which catalyzes a key metabolic step in the synthesis of starch in higher plants (Greene and Hannah, 1998). In addition to the apparent down regulation of starch synthesis, there was an increase in transcription of genes involved in starch hydrolysis. The transcription of a β-amylase-like genes, GRMZM2G025833, was upregulated during A. flavus pathogenesis.

Figure 2.

Enzymes in maize seed carbohydrate metabolism whose biosynthetic genes are differentially expressed in the A. flavus-maize interaction. Black arrows denote described carbohydrate metabolic pathways. Up or down directed block arrows indicate increased or decreased expression of genes, respectively. Numbers beside the enzymes corresponds to their description in Table 2.

Table 2.

Statistically significant differentially expressed genes referenced in Figure 2.

| Figure 2 References | Probe ID | Gene name | Putative protein | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TC302492_ZM_at | GRMZM2G394450 | Sucrose:sucrose fructosyltransferase (invertase1) | 2.3 |

| 1 | TC281577_ZM_s_at | GRMZM2G139300 | β-fructofuranosidase (invertase cell wall1) | 6.0 |

| 1 | TC309652_ZM_at | GRMZM2G123633 | β-fructofuranosidase (invertase cell wall3) | 1.3 |

| 2 | TC292194_ZM_at | GRMZM2G08037 | 6-phosphofructokinas | 2.2 |

| 3 | TC292194_ZM_at | GRMZM2G080375 | 6-phosphofructokinase | 1.7 |

| 4 | TC279919_ZM_x_at | GRMZM5G852968 | Triose-phosphate isomerase | 1.3 |

| 5 | TC310338_ZM_x_at | GRMZM2G046679 | Phosphopyruvate hydratase | 1.4 |

| 6 | TC289234_ZM_at | GRMZM2G051806 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | 1.8 |

| 7 | TC285970_ZM_s_at | GRMZM2G150098 | Pyruvate kinase | 2.1 |

| 8 | TC311287_ZM_at | GRMZM2G161566 | Shikimate kinase | 1.6 |

| 9 | TC299754_ZM_at | GRMZM2G138074 | 5-O-(4-coumaroyl)-D-quinate 3'-monooxygenase | 3.2 |

| 10 | TC310488_ZM_at | GRMZM2G429899 | Glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase (Sh2) | −1.6 |

| 11 | TC311334_ZM_at | GRMZM2G088753 | 1,4-alpha-glucan branching enzyme | −3.5 |

| 12 | TC311531_ZM_s_at | GRMZM2G127798 | Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (decarboxylating) | 1.5 |

| 13 | TC305088_ZM_at | GRMZM2G033208 | Transketolase | 2.0 |

Associated with changes in starch accumulation were changes in the mobilization of hexoses. Three maize invertases (GRMZM2G139300, GRMZM2G394450, GRMZM2G123633) were more highly expressed in the A. flavus infected kernels than in non-infected kernels (Table 2; Figure 2). Invertases are responsible for hydrolyzing sucrose into glucose and fructose (Cheng et al., 1996; Chourey et al., 2006), and are important in maize kernel development (Weber et al., 1997; Roitsch et al., 2003). Up regulation of invertases in the maize kernel is predicted to cause an increase in free hexose levels in the kernel and affect seed storage reserves such as starch.

The conversion of sucrose to hexoses also was associated with the down regulation of six genes involved with starch biosynthesis. Genes in the starch biosynthetic pathway [wx1 (GRMZM2G024993), su1 (GRMZM2G138060), ss1 (GRMZM2G129451), sbe1 (GRMZM2G088753), su2 (GRMZM2G348551), and ae1 (GRMZM2G032628)] as well as over 20 zein-annotated genes (Table S1) and the gene encoding the transcription factor that regulates 22-kD zein expression, opaque2 (GRMZM2G015534), were all down-regulated during infection.

It was not possible to determine the exact pathways of hexose remobilization in our studies, but gene expression in both the glycolytic pathway and the Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP) was altered by infection (Figure 2; Table 2). Before glucose can be utilized by either pathway, it must be phosphorylated by a hexokinase (Figure 2; Spielbauer et al., 2006). The fructokinase (GRMZM2G080375) was up regulated during pathogenesis. Hexose kinases have been associated with sugar sensing in plants and are potentially involved in the plant defense response (Granot et al., 2013). Glucose-6-phosphate also can be involved in starch synthesis, but because starch biosynthesis genes are down regulated it is likely used by other pathways for the production of energy or defense-related compounds during pathogenesis.

Up regulation of genes in the shikimate pathway supports the premise that hexoses are shunted away from starch synthesis in A. flavus infected kernels (Figure 2; Table 2). Several bioreactive compounds from this pathway are known to be involved in host defense (Daayf and Lattanzio, 2009). The shikimate pathway is an entry to aromatic secondary metabolism (Herrmann, 1995) and chorismate synthesized from this pathway is used to make the aromatic amino acids Phe, Tyr, and Trp. These amino acids are precursors for aromatic secondary metabolites including flavonoids and phytoalexins (Herrmann, 1995). Genes in the flavonoid pathway, fht1 [(GRMZM2G062396), c2 (GRMZM2G422750) (Bruce et al., 2000)] and genes from other phenypropanoid pathways (Table S1) increased in transcription after A. flavus inoculation.

The shikimic acid pathway also provides precursors for the biosynthesis of lignins (Herrmann, 1995), compounds associated with basal resistance to pathogens. Genes involved in lignin biosynthesis have been reported to be induced after A. flavus infection in both susceptible (VA35) (Kelley et al., 2012) and resistant varieties (Eyl25) (Luo et al., 2011) of maize. Liang et al. (2006) found lignin concentrations to increase in response to infection by A. flavus, and they found a negative correlation between lignin content of peanut cultivars and infection by A. flavus. Magbanua et al. (2013) following colonization by a GFP expressing strain of A. flavus, found less colonization of maize cob tissue in the resistant inbred Mp313e than in cobs of SC212m, a more susceptible genotype. They attributed the more restricted growth in Mp313e to the highly cross-linked lignin found in Mp313e. In our study, infection of maize kernels by A. flavus led to higher expression of three genes (GRMZM2G099420, GRMZM2G131205, GRMZM2G090980) involved in lignin biosynthesis (Table S1).

The carbohydrate metabolic methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway was also found differentially expressed during infection. The following genes from this pathway, which utilizes pyruvate from glycolysis to produces an assortment of isoprenoids including the hormone abscisic acid (ABA) were likewise up-regulated during A. flavus infection: (GRMZM2G056975, GRMZM2G493395, GRMZM2G172032, GRMZM2G027059, GRMZM5G859195). We found one gene, 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (GRMZM2G014392), involved in ABA synthesis up-regulated. The MEP pathway expression has been found induced in maize root colonized by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Lange et al., 2000; Walter et al., 2000).

Defense signaling pathways

Phytohormones are chemical compounds synthesized by the plant that regulate biochemical processes necessary for growth, reproduction, and survival. The plant defense response is hormonally regulated predominantly by the phytohoromones salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ET) (Niu et al., 2011; Mengiste, 2012; Derksen et al., 2013). Each hormone likely activates different components of the defense response system that are effective against specific pathogens. The JA/ET pathways are often induced in resistance to necrotrophic pathogens, whereas the SA pathway is typically induced by biotrophic and hemibiotrophic pathogens (Glazebrook, 2005; Derksen et al., 2013).

In this study kernel infection by A. flavus resulted in increased expression of the 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid reductases (OPR) encoding ZmOPR3 (GRMZM2G000236), and the alcohol dehydrogenase encoding ts2 (GRMZM5G840653). Expression of these genes has been linked with JA biosynthesis in maize (Vick and Zimmerman, 1984; Browse, 2009), and Ts2 has been associated with the hypersensitive response and resistance to Northern Leaf Blight in maize (Delong et al., 1993; Wisser et al., 2011). Our finding suggests that JA may be involved in the kernel-A. flavus interaction.

Other lipid-derived defense-related compounds besides JA are generated from enzymes generally associated with the JA-biosynthesis pathway. As an example, plants contain multiple LOX and OPR genes. In maize, the exact copy number of functional LOX genes varies between maize genotypes (De La Fuente et al., 2013). The function for most LOX and OPR isoenzymes is independent from JA biosynthesis. LOXs catalyze the formation of various oxidized lipids called oxylipins that can act as signaling molecules separate from JA and are thought to have antimicrobial properties (Blée, 2002; Prost et al., 2005). Oxylipins are known to effect fungal growth, including that of A. flavus, and mycotoxin production in seeds (Burow et al., 1997; Wilson et al., 2001; Brodhagen and Keller, 2006). The functional role for most OPR isoenzymes is unknown. ZmLOX and ZmOPR genes were previously found expressed in response to A. flavus and other maize fungal pathogen infections (Wilson et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2005). In accordance with these findings, we observed LOX and OPR genes differentially expressed during A. flavus kernel colonization. ZmLOX4, 7, and 9 (GRMZM2G109056, GRMZM2G070092, GRMZM2G017616) were up-regulated during A. flavus infection, whereas ZmLOX11 (GRMZM2G009479) was down-regulated. ZmOPR1, 2, 3, and 5 (GRMZM2G106303, GRMZM2G000236, GRMZM2G156712, GRMZM2G087192) were up-regulated in the diseased kernel with OPR1 and OPR3 having a 18 and 16 fold-change, respectively, (Table S1).

Whether JA and the other lipid-derived compounds increase maize resistance against pathogen attack may depend on the pathogen and which isoenzyme is expressed. Disruption of the ZmLOX3 results in enhanced resistance to F. verticillioides (Gao et al., 2009), Colletotrichum graminicola (Gao et al., 2007), Cochliobolus heterostrophus (Gao et al., 2007), and Exserohilum pedicellatum (Isakeit et al., 2007). However, the maize lox3 mutant shows increased susceptibility to A. flavus and A. nidulans, indicating this gene regulates disease resistance in a pathogen-specific manner (Gao et al., 2009).

Defense-associated genes in A. flavus infected seeds

Pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins are the hallmark of the induced defense response and their expression has been associated with resistance (van Loon et al., 2006; Luo et al., 2011). Several genes annotated as encoding for PR-proteins including those for chitinases [GRMZM2G112538, GRMZM2G477128, PR-10 (GRMZM2G075283).

GRMZM2G051943, GRMZM2G129189, GRMZM2G133781, chn2 (GRMZM2G145461), GRMZM2G145518, GRMZM2G162359] were up-regulated in the A. flavus infected kernels (Table S1). The expression of chitinase2 and PR-10 genes has been reported to be induced in fungal infected maize seed (Cordero et al., 1994). Furthermore, studies by Chen et al. (2006) showed that PR-10 has antifungal activity against A. flavus in vitro, and its production is increased upon A. flavus infection in the resistance line GT-MAS: gk, but not in the susceptible line Mo17. They also showed that repression of maize PR-10 by RNAi gene silencing resulted in increased susceptibility to A. flavus and aflatoxin production (Chen et al., 2010). A Bowman-Birk-like proteinase inhibitor (GRMZM2G156632), which encodes a PR-like protein showed a 2.5 fold increase in gene expression during infection (Rohrmeier and Lehle, 1993). This gene has been associated with the maize hypersensitive response (Simmons et al., 2002; Chintamanani et al., 2010).

The oxidative burst is an integral part of early plant immunity and is associated with reactive oxygen species, programmed cell death, and the hypersensitive response (Lamb and Dixon, 1997; Dickman and Fluhr, 2013). This defense cascade leads to the production of antimicrobial compounds. Associated with these defense responses are the production of peroxidases and gluathione-S-transferases (GST). Several genes encoding peroxidase-annotated genes (AC197758.3_FG004GRMZM2G080183, GRMZM2G089959, GRMZM2G095404, GRMZM2G103342, GRMZM2G108207, GRMZM2G138918, GRMZM2G149273, GRMZM2G173195, GRMZM2G320269, GRMZM2G321839, GRMZM2G382379, GRMZM2G419953, GRMZM2G441541, GRMZM2G471357) were up-regulated in the diseased kernels.

Four additional peroxidase-encoding genes (GRMZM2G034896, GRMZM2G089895, GRMZM2G103169, GRMZM2G315176) were down-regulated, implying that only certain peroxidase-isozymes are needed during A. flavus infection. Gluathione-S-transferases (GST) reduce host cellular damage by detoxifying toxins and xenobiotics commonly encountered during periods of disease and abiotic stress. Wisser et al. (2011) recently correlated ZmGST23 (NP_001104994.1) with moderate resistance to multiple maize pathogens. Though ZmGST23 was not differentially expressed in this study, the expression of GRMZM2G01909, predicted to encode a GST, had increased expression during A. flavus infection.

Validation of microarray data by qRT-PCR

In order to validate the results of the microarray study, the expression levels of five selected genes were monitored by qRT-PCR: (AC205274.3_FG001, GRMZM2G139300, GRMZM2G088753, GRMZM2G109056, GRMZM2G017616). The fold changes of these genes as determined by qRT-PCR were highly correlated with the results obtained from the microarrays (Table 3).

Table 3.

qRT-PCR results for select differentially expressed genes are consistent with microarray results.

| Gene name | Annotation | Fold change using microarray | Fold change using qRT-PCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| AC205274.3_FG001 | PRms (Pathogenesis related protein, maize seed) | 3.1 | 8.8 |

| GRMZM2G139300 | β-fructofuranosidase (invertase cell wall1) | 4.0 | 8.2 |

| GRMZM2G088753 | 1,4-alpha-glucan branching enzyme | −3.5 | −2.3 |

| GRMZM2G109056 | Lipoxygenase4 | 1.9 | 4.4 |

| GRMZM2G017616 | Lipoxygenase9 | 1.2 | 2.1 |

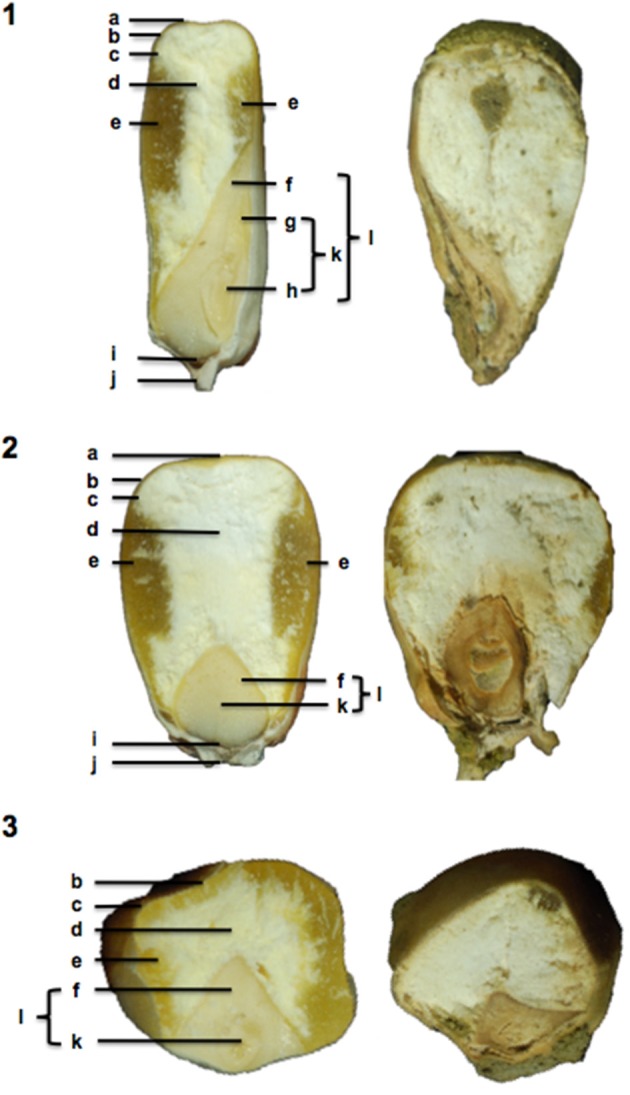

Physical changes within kernel in response to natural infection with A. flavus

The molecular analysis of maize gene expression during pathogenesis indicated major metabolic effects within kernels in response to infection by A. flavus. To determine if such effects could be manifest in the physical structure of kernels, we examined naturally infected kernels at the end of the growing season. Maize kernels adjacent to wound-inoculated kernels were harvested at maturity, dissected, and examined for growth of A. flavus and structural integrity. These kernels did not show any obvious wounds or cracks within their pericarp. Figure 3 shows a comparison of three representative infected kernels and non-infected kernels. The most striking modification was the reduced size of the zein-filled hard [horny] endosperm in infected kernels (Figure 3e). In diseased kernels the hard endosperm had been replaced with starchy endosperm (Figure 3d), but the consistency of the entire starchy endosperm was different from that of the non-infected kernel. Instead of being firm and intact, the starchy endosperm of the diseased kernel was fragile, friable, and filled with tiny air pockets. A. flavus could be discerned in some of these pockets including the gap between endosperm and germ (Figure 3d, l). Mycelium was also observed in the embryo around the plumule (Figure 3g) and primary root (Figure 3h), and the germ was discolored and shriveled (Figure 3f).

Figure 3.

Mature B73 kernels naturally infected with Aspergillus flavus. A sagittal (1) and frontal (2) and transversal (3) section of healthy B73 kernels (left) were compared to disease kernels (right) to discern any physical changes that occurred as a result of A. flavus. Bolded letters denote kernel parts and tissues: a—crown; b—pericarp; c—aleurone; d—starchy endosperm; e—hard endosperm; f—scutellar tissue; g—leaf primordia (plumule); h—primary root; i—transfer cells; j—pedicel; k—embryo; and l—germ.

Discussion

A. flavus kernel colonization is most aggressive on maize plants that have been subjected to heat or water stress (Tubajika and Damann, 2001; Scheidegger and Payne, 2003; Widstrom et al., 2003; Guo et al., 2008). Such conditions frequently occur throughout the world on rain-fed fields, and thus A. flavus colonization of kernels and subsequent contamination with aflatoxins is a concern internationally. Resistance to aflatoxin accumulation shows low heritability in the field, owing to the quantitative nature of resistance, the lack of reliable phenotyping, and strong genotype by environment (GxE) interactions. Thus, any approach that facilitates the identification of genes contributing to host resistance could accelerate the development of resistant maize genotypes.

The overall goal of this study was to better characterize host response to A. flavus opportunistic infection by identify maize genes differentially expressed during infection that could have applications as genetic markers in future breeding programs. Our previous research (Dolezal et al., 2013) showed that A. flavus follows a predictable pattern of colonization after inoculation of maize kernels. While all tissue types of the kernel can be colonized, growth of the fungus into scutellum tissue appears to follow the formation of a biofilm-like structure by A. flavus (Dolezal et al., 2013). The scutellum is metabolically active and known to synthesize numerous hydrolytic enzymes and defense-associated compounds (Casacuberta et al., 1991, 1992). Based on these studies, we chose 4 days after inoculation as the time to evaluate host response to A. flavus. Data presented in this study indicate that infected seed at this time to be transcriptionally responsive and express genes known to be involved in host defense.

Our observations show that B73 kernels mount a multipronged defense response to A. flavus typical of that associated with plant basal resistance. Many of the maize genes induced by A. flavus are important in resistance against maize foliar pathogens, underscoring a possible commonality of the resistance response in seeds and leaves. These data further suggest that A. flavus infection invokes defense tactics used against more aggressive maize pathogens including increased transcription of defense signaling pathways and genes several genes known to be involved in the host's defense response.

We also observed striking changes in the transcription of genes associated with carbohydrate utilization (Table S2). An analysis of these transcriptional changes leads us to conclude that infection by A. flavus decreases starch synthesis, increases starch degradation, and mobilizes hexoses into pathways associated with plant defense (Figure 2; Table 2). A physical examination of kernels naturally infected with A. flavus (Figure 3) showed changes in the structure of the maize endosperm that could reflect the remobilization of hexoses in the seed in response to infection.

Physical changes in seeds infected with fungi have been observed before (Fennell et al., 1973; Koltun et al., 1974; Huff, 1980; Shetty and Bhat, 1999; Cardwell et al., 2000; Pearson and Wicklow, 2006). Most researchers have speculated that hydrolytic enzymes secreted by infecting fungi are responsible for this loss in grain quality. However, maize mutants with abnormal expression levels of carbohydrate and protein biosynthetic pathway genes can also develop atypical endosperm tissue (Neuffer et al., 1997; Black et al., 2006). Our findings showing changes in kernel primary metabolism during A. flavus infection challenges the assumption that fungal produced enzymes are solely responsible for changes in kernel structure, and suggests the plant may also contribute to these changes through starch degradation and hexose mobilization away from starch synthesis.

While these metabolic changes could represent a defense response by the kernel to infection by A. flavus, the changes could instead promote host susceptibility to the pathogen. Fungi, particularly fungal plant pathogens, are capable of manipulating the plant's metabolism to create an environment advantageous for fungal growth (Govrin and Levine, 2000; Doehlemann et al., 2008). Increased invertase transcription in A. flavus infected kernels could indicate a higher-than-normal accumulation of free-hexoses within diseased tissue. Because glucose is the preferred carbon source of A. flavus, the up-regulation of sucrose hydrolyzing enzymes would presumable promote disease development by providing a steady supply of nutrients to the pathogen. IVR1 was previously found induced in sugar-poor environments, and its expression associated with tumor formation in Ustilago maydis infected maize (Xu et al., 1996; Doehlemann et al., 2008). Simple carbohydrates are also known to promote aflatoxin in maize kernels. Woloshuk et al. (1997) found an A. flavus α-amylase to play an important role in the production of aflatoxin by providing simple sugars conducive for aflatoxin production. Thus, sugar status in kernels could condition increased susceptibility as well as aflatoxin contamination.

In contrast, other studies have noted increased levels of hexoses in-and-around the site of pathogen infection and have hypothesized that these starch-derived sugars are an integral component of the host defense response (Berger et al., 2007; Bolton, 2009). Free-hexoses are thought to be used in the generation of reducing agents [NAD(P)H], energy [ATP], and pathway intermediates needed to synthesize secondary metabolite compounds. Their presence may also help trigger the synthesis of defense-related compounds.

Data from these studies, along with previous transcriptional studies (Luo et al., 2009, 2011; Jiang et al., 2011; Kelley et al., 2012), lay the groundwork for future studies investigating A. flavus resistance in maize. Under normal growth conditions, inducible defenses of B73 genotype may be adequate in inhibiting or at least slowing down A. flavus disease development. However, external and internal factors could affect this response. Abiotic stress, such as drought, can have a negative impact on the defense response (Wotton and Strange, 1987; Duke and Doehlert, 1996; Luo et al., 2010). Also, inherently low expression of defense and defense-associated genes may predispose the plant to greater infection (Chen et al., 2001; Alessandra et al., 2010). Genes expressed during infection may not necessarily be involved in resistance and could be causing increased susceptibility to fungal disease. Knowing which genes are typically expressed in response to pathogen attack is useful when examining how genotype and abiotic stress influence the infection process. Progress on more fully understanding disease development will ultimately leads to the development of genetically resistant cultivars.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/journal/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00384/abstract

References

- Alessandra L., Luca P., Adriano M. (2010). Differential gene expression in kernels and silks of maize lines with contrasting levels of ear rot resistance after Fusarium verticillioides infection. J. Plant Physiol. 167, 1398–1406 10.1016/j.jplph.2010.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson H. W., Nehring E. W., Wichser W. R. (1975). Aflatoxin contamination of corn in the field. Food Chem. 23, 775–782 10.1021/jf60200a014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B. 57, 289–300 [Google Scholar]

- Berger S., Sinha A., Roitsch T. (2007). Plant physiology meets phytopathology: plant primary metabolism and plant pathogen interactions. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 4019 10.1093/jxb/erm298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black M. J., Bewley J. D., Halmer P. (2006). The Encyclopedia of Seeds: Science, Technology and Uses Wallingford: CABI [Google Scholar]

- Blée E. (2002). Impact of phyto-oxylipins in plant defense. Trends Plant Sci. 7, 315–322 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02290-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddu J., Cho S., Muehlbauer G. J. (2007). Transcriptome analysis of trichothecene-induced gene expression in barley. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 20, 1364–1375 10.1094/MPMI-20-11-1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton M. (2009). Primary metabolism and plant defense- fuel for the fire. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22, 487–497 10.1094/MPMI-22-5-0487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodhagen M., Keller N. P. (2006). Signalling pathways connecting mycotoxin production and sporulation. Mol. Plant Pathol. 7, 285–301 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2006.00338.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M. P., Brown-Jenco C. S., Payne G. A. (1999). Genetic and molecular analysis of aflatoxin biosynthesis. Fungal Genet. Biol. 26, 81–98 10.1006/fgbi.1998.1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. L., Cleveland T. E., Payne G. A., Woloshuk C. P., Campbell K. W., White D. G. (1995). Determination of resistance to aflatoxin production in maize kernels and detection of fungal colonization using an Aspergillus flavus transformant expressing Escherichia coli β-glucuronidase. Phytopathology 85, 983–989 10.1094/Phyto-85-983 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Browse J. (2009). Jasmonate: preventing the maize tassel from getting in touch with his feminine side. Sci. Signal. 2 9 10.1126/scisignal.259pe9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce W., Folkerts O., Garnaat C., Crasta O., Roth B., Bowen B. (2000). Expression profiling of the maize flavonoid pathway genes controlled by estradiol-inducible transcription factors CRC and P. Plant Cell 12, 65–80 10.1105/tpc.12.1.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burow G. B., Nesbitt T. C., Dunlap J., Keller N. P. (1997). Seed lipoxygenase products modulate Aspergillus mycotoxin biosynthesis. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 10, 380–387 10.1094/MPMI.1997.10.3.380 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cardwell K. F., Kling J. G., Maziya-Dixon B., Bosque-Pérez N. A. (2000). Interactions between Fusarium verticillioides, Aspergillus flavus, and insect infestation in four maize genotypes in Lowland Africa. Phytopathology 90, 276–284 10.1094/PHYTO.2000.90.3.276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casacuberta J. M., Puigdomenech P., San Segundo B. (1991). A gene coding for a basic pathogenesis-related (PR-like) protein from Zea mays. Molecular cloning and induction by a fungus (Fusarium moniliforme) in germinating maize seeds. Plant Mol. Biol. 16, 527–536 10.1007/BF00023419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casacuberta J. M., Raventos D., Puigdomenech P., San Segundo B. (1992). Expression of the gene encoding the PR-like protein PRms in germinating maize embryos. Mol. Genet. Genomics 234, 97–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. Y., Brown R. L., Cleveland T. E., Damann K. E., Russin J. S. (2001). Comparison of constitutive and inducible maize kernel proteins of genotypes resistant or susceptible to aflatoxin production. J. Food Prot. 64, 1785–1792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. Y., Brown R. L., Damann K. E., Cleveland T. E. (2010). PR10 expression in maize and its effect on host resistance against Aspergillus flavus infection and aflatoxin production. Mol. Plant Pathol. 11, 69–81 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00574.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. Y., Brown R. L., Rajasekaran K., Damann K. E., Cleveland T. E. (2006). Identification of a maize kernel pathogenesis-related protein and evidence for its involvement in resistance to Aspergillus flavus infection and aflatoxin production. Phytopathology 96, 87–95 10.1094/PHYTO-96-0087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W. H., Taliercio E. W., Chourey P. S. (1996). The miniature1 seed locus of maize encodes a cell wall invertase required for normal development of endosperm and maternal cells in the pedicel. Plant Cell 8, 971–983 10.1105/tpc.8.6.971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chintamanani S., Hulbert S. H., Johal G. S., Balint-Kurti P. J. (2010). Identification of a maize locus that modulates the hypersensitive defense response, using mutant-assisted gene identification and characterization. Genetics 184, 813–825 10.1534/genetics.109.111880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chourey P. S., Jain M., Li Q. B., Carlson S. J. (2006). Genetic control of cell wall invertases in developing endosperm of maize. Planta 223, 159–167 10.1007/s00425-005-0039-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero M., Raventos D., Segundo B. (1994). Differential expression and induction of chitinases and β-1, 3-glucanases in response to fungal infection during germination of maize seeds. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 7, 23–31 10.1094/MPMI-7-0023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daayf F., Lattanzio V. (2009). Recent Advances in Polyphenol Research. Vol. 1 New York, NY: Wiley InterScience, 47–56 [Google Scholar]

- De La Fuente G. N., Murray S. C., Isakeit T., Park Y. S., Yan Y., Warburton M. L., et al. (2013). Characterization of genetic diversity and linkage disequilibrium of ZmLOX4 and ZmLOX5 loci in maize. PLoS ONE 8:e53973 10.1371/journal.pone.0053973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delong A., Calderon-Urrea A., Dellaporta S. L. (1993). Sex determination gene TASSELSEED2 of maize encodes a short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase required for stage-specific floral organ abortion. Cell 74, 757–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derksen H., Rampitsch C., Daayf F. (2013). Signaling cross-talk in plant disease resistance. Plant Sci. 207, 79–87 10.1016/j.plantsci.2013.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman M. B., Fluhr R. (2013). Centrality of host cell death in plant-microbe interactions. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 51, 543–570 10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-173027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd J. L. (1980). The role of plant stresses in development of corn stalk rots. Plant Dis. 64, 533–537 10.1094/PD-64-533 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doehlemann G., Wahl R., Horst R. J., Voll L. M., Usadel B., Poree F., et al. (2008). Reprogramming a maize plant: transcriptional and metabolic changes induced by the fungal biotroph Ustilago maydis. Plant J. 56, 181–195 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03590.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal A. L., Obrian G. R., Nielsen D. M., Woloshuk C. P., Boston R. S., Payne G. A. (2013). Localization, morphology and transcriptional profile of Aspergillus flavus during seed colonization. Mol. Plant Pathol. 14, 898–909 10.1111/mpp.12056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z., Zhou X., Ling Y., Zhang Z., Su Z. (2010). agriGO: a GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W64–W70 10.1093/nar/gkq310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke E., Doehlert D. (1996). Effects of heat stress on enzyme activities and transcript levels in developing maize kernels grown in culture. Environ. Exp. Bot. 36, 199–208 10.1016/0098-8472(96)01004-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fennell D., Bothast R., Lillehoj E., Peterson R. (1973). Bright greenish-yellow fluorescence and associated fungi in white corn naturally contaminated with aflatoxin. Cereal Chem. 50, 404–413 [Google Scholar]

- Gao X., Brodhagen M., Isakeit T., Brown S. H., Gobel C., Betran J., et al. (2009). Inactivation of the lipoxygenase ZmLOX3 increases susceptibility of maize to Aspergillus spp. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22, 222–231 10.1094/MPMI-22-2-0222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X., Shim W. B., Gobel C., Kunze S., Feussner I., Meeley R., et al. (2007). Disruption of a maize 9-lipoxygenase results in increased resistance to fungal pathogens and reduced levels of contamination with mycotoxin fumonisin. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 20, 922–933 10.1094/MPMI-20-8-0922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook J. (2005). Contrasting mechanisms of defense against biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 43, 205–227 10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.040204.135923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govrin E. M., Levine A. (2000). The hypersensitive response facilitates plant infection by the necrotrophic pathogen Botrytis cinerea. Curr. Biol. 10, 751–757 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00560-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granot D., David-Schwartz R., Kelly G. (2013). Hexose kinases and their role in sugar-sensing and plant development. Front. Plant Sci. 4:44 10.3389/fpls.2013.00044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene T. W., Hannah L. C. (1998). Maize endosperm ADP–glucose pyrophosphorylase SHRUNKEN2 and BRITTLE2 subunit interactions. Plant Cell 10, 1295–1306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo B., Chen Z. Y., Lee R. D., Scully B. T. (2008). Drought stress and preharvest aflatoxin contamination in agricultural commodity: genetics, genomics and proteomics. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 50, 1281–1291 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00739.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann K. M. (1995). The shikimate pathway as an entry to aromatic secondary metabolism. Plant Physiol. 107, 7–12 10.1104/pp.107.1.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruska Z., Yao H., Kincaid R., Darlington D., Brown R. L., Bhatnagar D., et al. (2013). Fluorescence Imaging Spectroscopy (FIS) for comparing spectra from corn ears naturally and artificially infected with aflatoxin producing fungus. J. Food Sci. 78, T1313–T1320 10.1111/1750-3841.12202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huff W. (1980). A physical method for the segregation of aflatoxin-contaminated corn. Cereal Chem. 57, 236–238 [Google Scholar]

- Isakeit T., Gao X., Kolomiets M. (2007). Increased resistance of a maize mutant lacking the 9-lipoxygenase gene, ZmLOX3, to root rot caused by Exserohilum pedicellatum. Phytopathology 155, 758–760 10.1111/j.1439-0434.2007.01301.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T., Zhou B., Luo M., Abbas H. K., Kemerait R., Lee R. D., et al. (2011). Expression analysis of stress-related genes in kernels of different maize (Zea mays L.) inbred lines with different resistance to aflatoxin contamination. Toxins (Basel) 3, 538–550 10.3390/toxins3060538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. D. G., Dangl J. L. (2006). The plant immune system. Nature 444, 323–329 10.1038/nature05286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. K., Duncan H. E., Payne G. A., Leonard K. J. (1980). Factors influencing infection by Aspergillus flavus in silk-inoculated corn. Plant Dis. 64, 859–863 10.1094/PD-64-859 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keller N. P., Butchko R., Sarr B., Phillips T. D. (1994). A visual pattern of mycotoxin production in maize kernels by Aspergillus spp. Phytopathology 84, 483–488 10.1094/Phyto-84-483 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley R. Y., Williams W. P., Mylroie J. E., Boykin D. L., Harper J. W., Windham G. L., et al. (2012). Identification of maize genes associated with host plant resistance or susceptibility to Aspergillus flavus infection and aflatoxin accumulation. PLoS ONE 7:e36892 10.1371/journal.pone.0036892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kew M. C. (2013). Aflatoxins as a cause of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Gastrointestin. Liver Dis. 22, 305–310 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler B. (1942). Natural mode of entrance of fungi into corn ears and some symptoms that indicate infection. J. Agric. Res. 64, 421–442 [Google Scholar]

- Koltun S. P., Gardner H. K., Dollear F. G., Rayner E. T. (1974). Physical properties and aflatoxin content of individual cateye fluorescent cottonseeds. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 51, 178–180 10.1007/BF02639734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb C., Dixon R. (1997). The oxidative burst in plant disease resistance. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 48, 251–275 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange B. M., Rujan T., Martin W., Croteau R. (2000). Isoprenoid biosynthesis: the evolution of two ancient and distinct pathways across genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 13172–13177 10.1073/pnas.240454797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X. Q., Luo M., Guo B. Z. (2006). Resistance mechanisms to Aspergillus flavus infection and aflatoxin contamination in peanut (Arachis hypogaea). Plant Pathol. J. 5, 115–124 10.3923/ppj.2006.115.12421118527 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lillehoj E., Kwolek W., Horner E., Widstrom N., Josephson L., Franz A., et al. (1980). Aflatoxin contamination of preharvest corn: role of Aspergillus flavus inoculum and insect damage. Cereal Chem. 57, 255–257 [Google Scholar]

- Lillehoj E. B., Kwolek W. F., Peterson R. E., Shotwell O. L., Hesseltine C. W. (1976). Aflatoxin contamination, fluorescence, and insect damage in corn infected with Aspergillus flavus before harvest. Cereal Chem. 53, 505–512 [Google Scholar]

- Luo M., Brown R. L., Chen Z. Y., Cleveland T. E. (2009). Host genes involved in the interaction between Aspergillus flavus and maize. Toxin Rev. 28, 118–128 10.1080/15569540903089197 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M., Brown R. L., Chen Z. Y., Menkir A., Yu J., Bhatnagar D. (2011). Transcriptional profiles uncover Aspergillus flavus-induced resistance in maize kernels. Toxins (Basel) 3, 766–786 10.3390/toxins3070766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M., Liu J., Lee R. D., Scully B. T., Guo B. (2010). Monitoring the expression of maize genes in developing kernels under drought stress using oligo-microarray. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 52, 1059–1074 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.01000.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magbanua Z., Williams W. P., Luthe D. (2013). The maize rachis affects Aspergillus flavus spread during ear development. Maydica 58, 182–188 [Google Scholar]

- Marsh S., Payne G. (1984). Preharvest infection of corn silks and kernels by Aspergillus flavus. Phytopathology 74, 1284–1289 10.1094/Phyto-74-128416637189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mengiste T. (2012). Plant immunity to necrotrophs. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 50, 267–294 10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-172955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mideros S. X., Warburton M. L., Jamann T. M., Windham G. L., Williams W. P., Nelson R. J. (2014). Quantitative trait loci influencing mycotoxin contamination of maize: analysis by linkage mapping, characterization of near-isogenic lines, and meta-analysis. Crop Sci. 54, 127–142 10.2135/cropsci2013.04.0249 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mylroie J. E., Warburton M. L., Wilkinson J. R. (2013). Development of a gene-based marker correlated to reduced aflatoxin accumulation in maize. Euphytica 194, 431–441 10.1007/s10681-013-0973-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neuffer M., Coe J. E., Wessler S. (1997). Mutants of Maize. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press [Google Scholar]

- Niu D. D., Liu H. X., Jiang C. H., Wang Y. P., Wang Q. Y., Jin H. L., et al. (2011). The plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium bacillus cereus AR156 induces systemic resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana by simultaneously activating salicylate- and jasmonate/ethylene-dependent signaling pathways. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 24, 533–542 10.1094/MPMI-09-10-0213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne A. G., Yu J. (2010). Ecology, Development and Gene Regulation in Aspergillus flavus. Aspergillus: Molecular Biology and Genomics. Norfolk: Masayuki Machida and Katsuya Gomi Caister Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Payne G., Hagler W., Jr, Adkins C. (1988a). Aflatoxin accumulation in inoculated ears of field grown maize. Plant Dis. 72, 422–424 10.1094/PD-72-0422 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Payne G., Thompson D., Lillehoj E., Zuber M., Adkins C. (1988b). Effect of temperature on the preharvest infection of maize kernels by Aspergillus flavus. Phytopathology 78, 1376–1380 10.1094/Phyto-78-1376 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson T., Wicklow D. (2006). Detection of corn kernels infected by fungi. Trans. ASABE 49, 1235–1245 10.13031/2013.21723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prost I., Dhondt S., Rothe G., Vicente J., Rodriguez M. J., Kift N., et al. (2005). Evaluation of the antimicrobial activities of plant oxylipins supports their involvement in defense against pathogens. Plant Physiol. 139, 1902–1913 10.1104/pp.105.066274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese B. N., Payne G. A., Nielsen D. M., Woloshuk C. P. (2011). Gene expression profile and response to maize kernels by Aspergillus flavus. Phytopathology 101, 797–804 10.1094/PHYTO-09-10-0261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie S., Hanway J., Benson G. (1997). How a Corn Plant Develops. Special Report Number 48. Ames, IA: Iowa State University of Science and Technology Cooperative Extension Service [Google Scholar]

- Robert-Seilaniantz A., Grant M., Jones J. D. G. (2011). Hormone crosstalk in plant disease and defense: more than just JASMONATE-SALICYLATE antagonism. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 49, 317–343 10.1146/annurev-phyto-073009-114447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrmeier T., Lehle L. (1993). WIP1, a wound-inducible gene from maize with homology to bowman-birk proteinase inhibitors. Plant Mol. Biol. 22, 783–792 10.1007/BF00027365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roitsch T., Balibrea M. E., Hofmann M., Proels R., Sinha A. K. (2003). Extracellular invertase: key metabolic enzyme and PR protein. J. Exp. Bot. 54, 513–524 10.1093/jxb/erg050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheidegger K. A., Payne G. A. (2003). Unlocking the secrets behind secondary metabolism: a review of Aspergillus flavus from pathogenicity to functional genomics. Toxin Rev. 22, 423–459 10.1081/TXR-120024100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty P., Bhat R. (1999). A physical method for segregation of fumonisin-contaminated maize. Food Chem. 66, 371–374 10.1016/S0308-8146(99)00052-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons C., Tossberg J., Sandahl G., Marsh W., Dowd P., Duvick J., et al. (2002). Maize pathogen defenses activated by avirulence gene avrRxv. Maize Genet. Coop. News Lett. 76, 40–41 [Google Scholar]

- Smart M. G., Wicklow D. T., Caldwell R. W. (1990). Pathogenesis in Aspergillus ear rot of maize: light microscopy of fungal spread from wounds. Phytopathology 80, 1287–1294 10.1094/Phyto-80-1287 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C. A., Robertson D., Yates B., Nielsen D. M., Brown D., Dean R. A., et al. (2008). The effect of temperature on Natural Antisense Transcript (NAT) expression in Aspergillus flavus. Curr. Genet. 54, 241–269 10.1007/s00294-008-0215-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielbauer G., Margl L., Hannah L. C., Römischb W., Ettenhuber C., Bacher A., et al. (2006). Robustness of central carbohydrate metabolism in developing maize kernels. Phytochemistry 67, 1460–1475 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.05.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubenhaus J. J. (1920). A study of the black and yellow molds of ear corn. Texa Agric. Exp. Station Bull 290, 3 [Google Scholar]

- Tubajika K. M., Damann K. E. (2001). Sources of resistance to aflatoxin production in maize. J. Agric. Food Chem. 49, 2652–2656 10.1021/jf001333i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Loon L. C., Rep M., Pieterse C. M. J. (2006). Significance of inducible defense-related proteins in infected plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 44, 135–162 10.1146/annurev.phyto.44.070505.143425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vick B. A., Zimmerman D. C. (1984). Biosynthesis of jasmonic acid by several plant species. Plant Physiol. 75, 458–461 10.1104/pp.75.2.458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter M. H., Fester T., Strack D. (2000). Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi induce the non-mevalonate methylerythritol phosphate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis correlated with accumulation of the yellow pigment and other apocarotenoids. Plant J. 21, 571–578 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00708.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton M. L., Williams W. P., Windham G. L., Murray S. C., Xu W., Hawkins L. K., et al. (2013). Phenotypic and genetic characterization of a maize association mapping panel developed for the identification of new sources of resistance to Aspergillus flavus and aflatoxin accumulation. Crop Sci. 53, 2374–2383 10.2135/cropsci2012.10.0616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weber H., Borisjuk L., Wobus U. (1997). Sugar import and metabolism during seed development. Trends Plant Sci. 2, 169–174 10.1016/S1360-1385(97)85222-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Widstrom N. W., Guo B. Z., Wilson D. M. (2003). Integration of crop management and genetics for control of preharvest aflatoxin contamination of corn. Toxin Rev. 22, 199–227 10.1081/TXR-120024092 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R. A., Gardner H. W., Keller N. P. (2001). Cultivar-dependent expression of a maize lipoxygenase responsive to seed infesting fungi. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 14, 980–987 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.8.980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windham G., Williams W. (1998). Aspergillus flavus infection and aflatoxin accumulation in resistant and susceptible maize hybrids. Plant Dis. 82, 281–284 10.1094/PDIS.1998.82.3.281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windham G. L., Williams W. P. (2002). Evaluation of corn inbreds and advanced breeding lines for resistance to aflatoxin contamination in the field. Plant Dis. 86, 232–234 10.1094/PDIS.2002.86.3.232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisser R. J., Kolkman J. M., Patzoldt M. E., Holland J. B., Yu J., Krakowsky M., et al. (2011). Multivariate analysis of maize disease resistances suggests a pleiotropic genetic basis and implicates a GST gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 7339–7344 10.1073/pnas.1011739108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woloshuk C. P., Cavaletto J. R., Cleveland T. E. (1997). Inducers of aflatoxin biosynthesis from colonized maize kernels are generated by an amylase activity from Aspergillus flavus. Phytopathology 87, 164–169 10.1094/PHYTO.1997.87.2.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wotton H., Strange R. (1987). Increased susceptibility and reduced phytoalexin accumulation in drought-stressed peanut kernels challenged with Aspergillus flavus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53, 270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Avigne T. W., McCarty D. R., Koch K. E. (1996). A similar dichotomy of sugar modulation and developmental expression affects both paths of sucrose metabolism: evidence from a maize invertase gene family. Plant Cell 8, 1209–1220 10.1105/tpc.8.7.1209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Simmons C., Yalpani N., Crane V., Wilkinson H., Kolomiets M. (2005). Genomic analysis of the 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid reductase gene family of Zea mays. Plant Mol. Biol. 59, 323–343 10.1007/s11103-005-8883-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.