Abstract

A reconstruction algorithm for diffuse optical tomography (DOT) based on diffusion theory and finite element method is described. The algorithm reconstructs the optical properties in a permissible domain or region of interest to reduce the number of unknowns. The algorithm can be used to reconstruct optical properties for a segmented object (where a CT-scan or MRI is available) or a non-segmented object. For the latter, an adaptive segmentation algorithm merges contiguous regions with similar optical properties thereby reducing the number of unknowns. In calculating the Jacobian matrix the algorithm uses an efficient direct method so the required time is comparable to that needed for a single forward calculation. The reconstructed optical properties using segmented, non-segmented, and adaptively segmented 3D mouse anatomy (MOBY) are used to perform bioluminescence tomography (BLT) for two simulated internal sources. The BLT results suggest that the accuracy of reconstruction of total source power obtained without the segmentation provided by an auxiliary imaging method such as x-ray CT is comparable to that obtained when using perfect segmentation.

1. Introduction

Diffuse optical tomography (DOT) and bioluminescence tomography (BLT) are noninvasive techniques that can visualize disease progression and response to treatment (Ntziachristos et al 2005, Weissleder and Mahmood 2001, Willmann et al 2008, Tian et al 2008). Using the boundary measurement of light scattered by tissue, DOT reconstructs the tissue optical properties (e.g. scattering and absorption) which may give insight into tissue physiology. Bioluminescence tomography (BLT) attempts to reconstruct the three dimensional distribution of a bioluminescent source (i.e. optical power per unit volume) and to provide true quantitative information about its magnitude and location (Chaudhari et al 2005, Ahn et al 2008, Comsa et al 2006, Kuo et al 2007, and Dehghani et al 2006). Both DOT and BLT are non-linear ill-posed inverse problems and the solutions are usually pursued as minimization problems (Cong et al 2005, He et al 2010, Huang et al 2010, Feng et al 2008, Lu et al 2009, Mohajerani et al 2007, Cao et al 2007, Gu et al 2004, Slavine et al 2006, Chen et al 2010, Alexandrakis et al 2005). This requires repetitive solutions of a forward model of light propagation from the source to the animal surface. The accuracy of the BLT solution depends on the accuracy of the tissue optical properties used in the forward calculations. Therefore developing a simple and accurate DOT algorithm is important for good BLT results.

In addition to the forward model, the DOT requires calculation of the Jacobian which gives the derivative of the light fluence rates at the boundary with respect to the scattering and absorption coefficients at all nodes inside the animal. The approximate adjoint method is usually used for calculating the Jacobian (Marchuk 1995 and Marchuk et al 1996). and regularization is required for the minimization solver. The ill-posedness of the solution can be reduced using hard or soft prior information obtained from an adjuvant imaging method such as x-ray CT (Yalavarthy et al 2007). Automatic segmentation of the CT image to produce priors may be challenging because of inadequate contrast. In this paper we propose an alternative strategy for DOT that incorporates several novel features. First, the reconstruction of the optical properties is restricted to a region-of-interest where an accurate solution is required. This reduces the number of unknowns and accelerates the solution. Second, the Jacobian is calculated exactly using an efficient direct method that requires about as much time as forward solution iteration. Third, the system of equations for the DOT minimization problem is normalized so that all nodes have the same sensitivity regardless of their location. This scheme avoids regularization and the correct solution is obtained by re-scaling the solution in the normalized space. Finally, the algorithm provides artificial segmentation to improve the resolution of the solution. The segmentation is adaptive and uses the solution from a previous iteration to combine nearby nodes that have similar values for scattering or absorption into one region. In this way the number of unknowns is iteratively reduced and better contrast solutions can be obtained.

Several investigators have concluded that better BLT reconstructions can be achieved if forward calculations take into account the true three dimensional distributions of scattering and absorption coefficients. In previous papers (Naser and Patterson 2010 and 2011) we have described a strategy whereby this information can be obtained by diffuse optical tomography (DOT). However, our previous DOT algorithms assumed that different tissue types are clearly identified by segmentation of CT scans. In this paper we study how different approaches to the DOT problem affect the accuracy of the final BLT solution. We compare: a) the simplest method wherein the DOT data are used to generate a homogenous estimate of the optical properties, b) a DOT solution that is restricted to a region-of-interest in the vicinity of the bioluminescence sources, c) an adaptive segmentation method where the number of unknowns in the DOT problem is iteratively reduced, d) a "perfect" segmentation provided by some kind of auxiliary imaging method.

2. DOT algorithm

The frequency domain diffusion equation and the Robin-type boundary condition at a specific wavelength are given by (Arridge 1999 and Klose 2007).

| Equation 1 |

| Equation 2 |

where φ(r, λ, ω) is the light fluence rate at position r, wavelength λ, and light modulation frequency f given by ω = 2πf ; Ω and ∂Ω are the domain and its boundary respectively, and the source distribution is given by s (r, ω, λ). The spatial distribution of the tissue optical properties at wavelength λ is given by the absorption coefficient μa (r, λ) and the diffusion coefficient κ(r, λ), where the diffusion coefficient is defined by , where is the reduced scattering coefficient , μs is the scattering coefficient and g is the anisotropy factor. n̂(r) is a unit vector pointed outwardly normal to ∂Ω, and ξ is derived from Fresnel’s law as (Dehghani et al 2008) ξ = ((2/(1 − R0)) − 1 + |cos θc|3)/(1 − |cos θc|2), where the critical angle θc = sin−1 (1/n) and R0 = (n − 1)2/(n + 1)2 and n is the tissue refractive index and the refractive index of the surrounding medium is assumed to be 1.

Equation (1) can be solved numerically using the method of finite elements (FE) (Arridge et al 1993, Schweiger et al 1993, and Jiang 1998), and the discrete version of Equation (1) is given by

| Equation 3 |

where A is the forward matrix obtained by discretizing the diffusion operator in Equation (1). If the FE mesh contains N nodes, the number of unknown optical coefficients is 2N and the optical properties vector can be written in its transpose form as , where and μan are the scattering and absorption coefficients at the node n. Differentiating both sides of Equation (3) with respect to μn gives

| Equation 4 |

where the differentiation of the source with respect to the optical properties gives zero since the source is not a function of the optical properties. Therefore, the first order derivative of the light fluence rate with respect to the scattering or absorption coefficients at node n is obtained from (4)

| Equation 5 |

A−1 and ϕ are calculated once using the forward calculation of Equation (3). The derivatives of the matrix A with respect to the scattering and absorption coefficients of all nodes are calculated as follows:

Using the FE to obtain Equation (3) (Volakis et al 1998), the assembly matrix A is obtained by adding up the matrices corresponding to all elements of the mesh such that

| Equation 6 |

where Nl is the number of mesh elements. All elements of the matrix Al are zeros except the elements corresponding to the 4 nodes of the tetrahedron element l. Therefore

| Equation 7 |

where t(l,:) is the node index of element l and αl and βl are constant matrices that are functions of the nodes coordinates and are defined in the appendix. κl and are the average values of the diffusion and absorption coefficients of the element l and are given by

| Equation 8 |

where t(l,m)is the index of the local node m of element l. Using Equations (6), (7), and (8), the derivatives of the matrix A with respect to scattering and absorption coefficients at node n are obtained analytically and are given by

| Equation 9 |

where

| Equation 10 |

The first order derivative of the light fluence rate with respect to the optical properties at the detectors around the object is given by

| Equation 11 |

where d is the detector index and ϕd is a vector of length Nd, where Nd is the number of detectors and the matrix A−1(d,:) consists of the d rows and all columns of the matrix A−1. In order to calculate the derivatives at all nodes, A−1(d,:) and ϕ need to be calculated explicitly which requires a cost comparable to a forward calculation. For a phasor representation of the light fluence rate where ϕd = φdeiθd and for a FE mesh of N nodes, the Jacobian is given by (Naser et al 2012)

| Equation 12 |

where (Naser et al 2012)

| Equation 13 |

If the detectors do not coincide with the FE nodes at the boundary, interpolation can be used to get the value from the surrounding nodes. It is assumed that the values of the light fluence rate at the detector locations can be obtained from the measurements of the corresponding pixels of the CCD camera used for imaging. The measurements of the CCD camera provide only the magnitude of the fluence rate, however the developed DOT algorithm can consider also the frequency domain case where both magnitude and phase of the fluence rate are available. Both continuous wave and frequency domain cases are considered by the DOT algorithm to show the best possible results.

The light fluence rate captured by the detectors around the object can be approximated by a first order Taylor expansion such that

| Equation 14 |

where φd0 and θd0 are the magnitude and phase of the light fluence rate corresponding to the initial guess μ0. In matrix form, Equation (9) is given by

| Equation 15 |

which can be concisely written as

| Equation 16 |

For multiple external sources, measured data are obtained for each source and so Equation (11) for Ns sources is modified to

| Equation 17 |

Assume that the object is segmented into NR regions where, for each region, all nodes in the region have the same scattering and absorption coefficients. For a region i, index{i} is an array that contains the list of nodes in region i. Therefore, Equation (17) can be written as

| Equation 18 |

By segmenting the object, the total number of variables is reduced from (the number of nodes × 2) to (the number of regions × 2) which reduces the ill-posedness of the problem. The optical properties can be obtained by solving the following minimization problem.

| Equation 19 |

where dμmin = μmin − μ0 and dμmax = μmax − μ0. The minization problem in Equation (19) is not sensitivity independent as the nodes or regions close to the object surface have more sensitivity or larger Jacobian magnitudes than nodes or regions deep inside the object. The minimization problem is solved after normalizing the Jacobian matrix such that

| Equation 20 |

where

| Equation 21 |

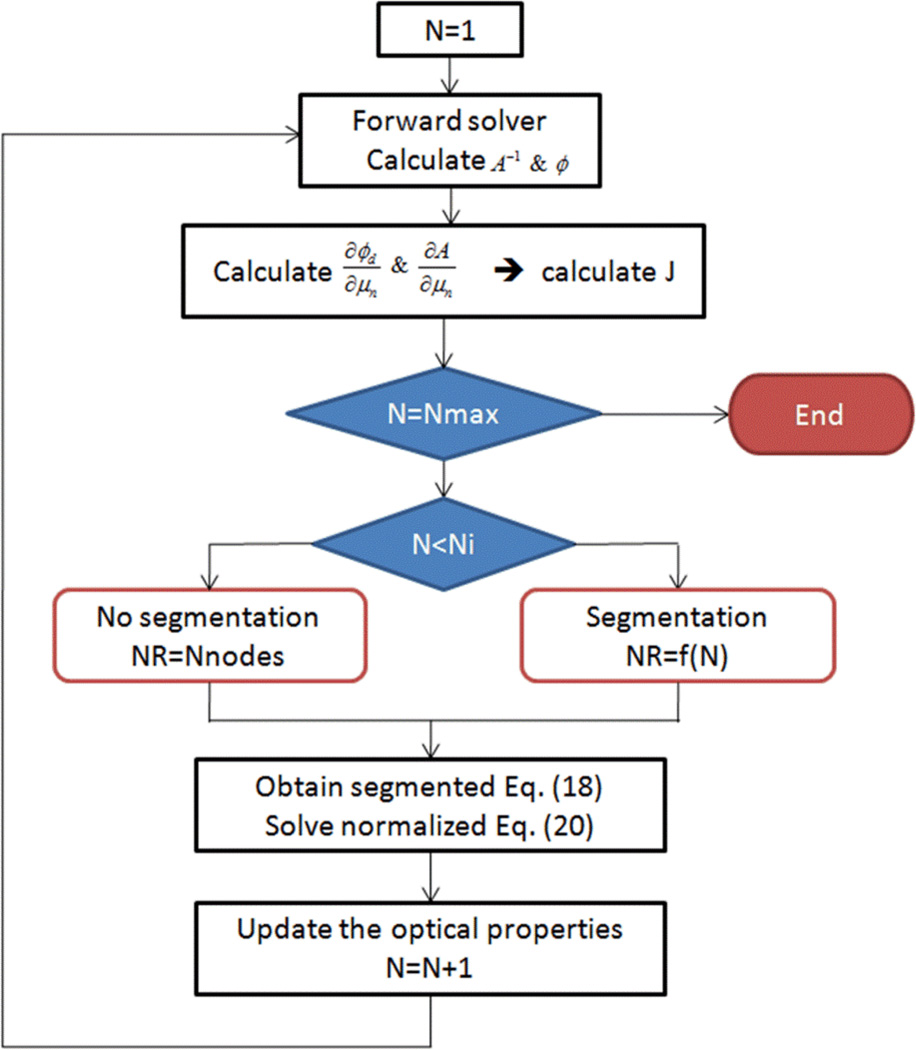

The flowchart describing the iterative solution for the optical properties reconstruction is shown in Figure 1. The flowchart shows Nmax iterations to solve the normalized minimization problem in Equation (20). The first Ni iterations (Ni=3) are solved without segmentation (i.e. the number of regions NR equals the total number of nodes) to make sure a stable solution is established before starting the segmentation, while the rest of the iterations are solved after doing segmentation where NR equals f(N) and N is the iteration number. We choose an exponentially decreasing function to reduce the number of regions in each iteration, such that f(N) = NRiCN−1 and , where NRi is the initial number of regions, NRf is the final number of regions, and NIT is the total number of iterations.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for the iterative solution algorithm for DOT using adaptive segmentation.

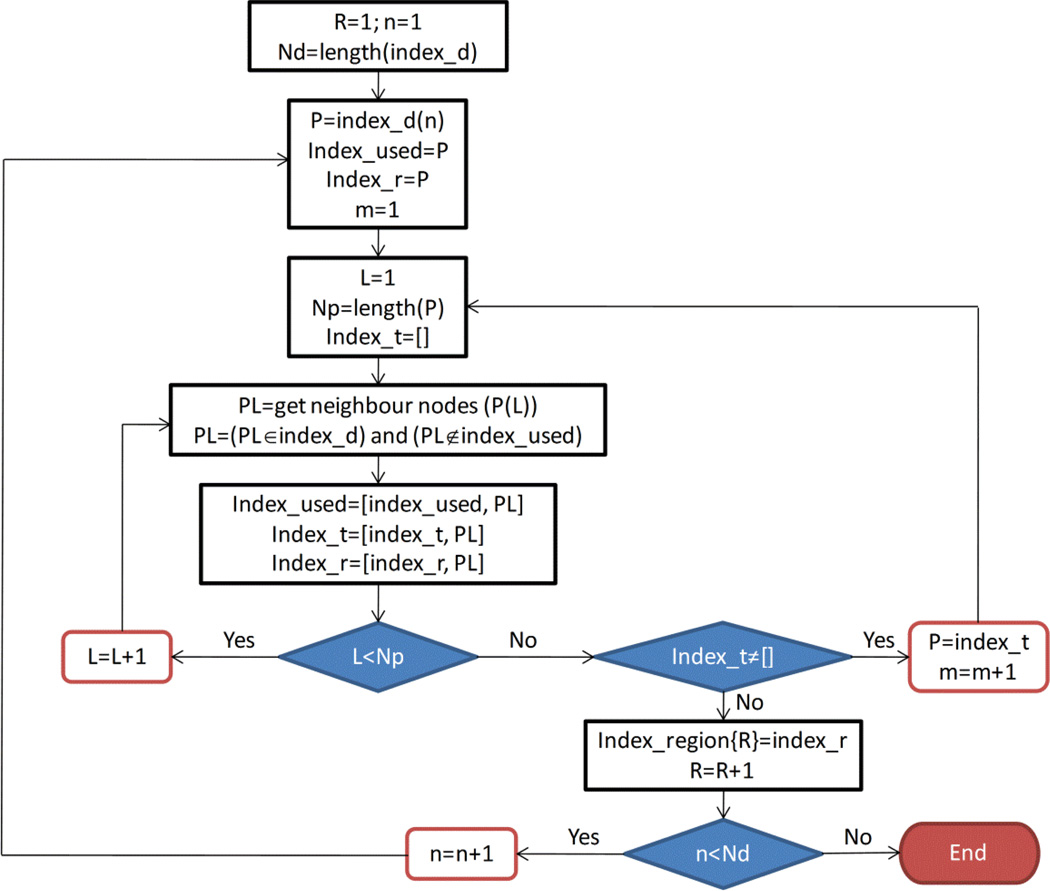

3. Segmentation

The adaptive segmentation uses the values of the reconstructed optical properties from a previous iteration to divide the object space into regions where all nodes of each region are assumed to have the same optical properties. The segmentation is started by dividing the absorption coefficient into a specified number of domains. Choosing a large number of domains leads to a large number of unknowns which is similar to the case of non-segmented object, while choosing a small number of domains can erroneously combine different tissue types in the same region. Choosing a relatively small number of domains that leads to a number of regions larger than the number of tissue types gives good results. In the segmentation algorithm, we started with the total number of nodes to be the number of domains and then iteratively reduced to 20 domains in the last iteration. To obtain the index of nodes related to one region, first the absorption coefficient is divided into a specified number of domains. The nodes where the absorption coefficient lies in that domain will be grouped together as one region as long as all these nodes are connected and not separated by other nodes that have absorption outside the domain. Otherwise, the nodes will be grouped into more than one region, so that each region contains nodes that are connected and has absorption coefficient within the specified domain. The flowchart (Figure 2) describes the segmentation of a group of nodes represented by index_d. The algorithm in the flowchart groups these nodes in one region or more depending on whether these nodes are connected. The index of these regions is stored in the list of arrays Index_region. The Index_used array includes the nodes that are already grouped and therefore to be removed from the list, index_r includes the current group of nodes R to be stored in the index_region{R}, and index_t is an array to store the neighbor nodes to the current node which are not yet added to the current region index_region{R}. The algorithm has two internal loops which are L and m and one outer loop which is loop n. The loop L obtains all the neighbor nodes to the current node to be in the same region with the current node. The loop m recall the loop L after changing the current node to be a list of nodes that includes the neighbor nodes obtained from the prvious call of loop L. After finishing the loops L and m, the list of nodes related to one region is stored in index_region{R}. The outer loop n starts with a different node to start forming a new region.

Figure 2.

Flowchart describing the iterative segmentation algorithm for the iterative solution algorithm.

4. Results and discussion

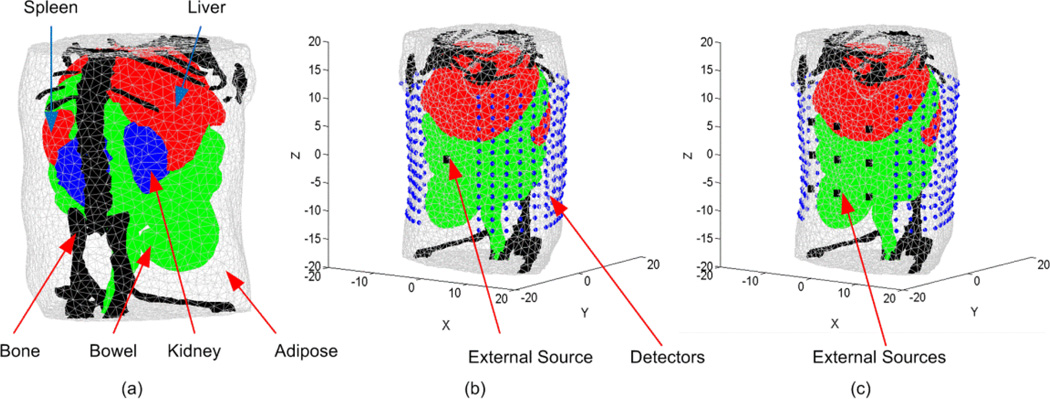

To demonstrate the DOT algorithm, a highly detailed anatomy for a laboratory mouse (MOBY) (Segars et al 2004) was used to create the FE mesh. The 3D object (Figure 3(a)) represents a finite element mesh of a section of a mouse abdomen where adipose, liver and spleen, bowel, kidney, and bone tissues are identified and assigned realistic wavelength-dependent optical properties. It is assumed that all elements within each region have the same optical properties. Two different setups for the detectors and external sources were used in the simulations. The first, shown in Figure 3(b), assumes that multiple views can be obtained around the animal and 12 optical fibers are used as external sources uniformly distributed around the object at 30° increments (one source of the 12 is shown in Figure 3(b)). Associated with each source are 390 detectors consisting of 13 layers where each layer consists of 30 detectors forming a field of view of 300°. It is assumed that these source fibers produce Gaussian sources located one transport length inside the object (~ 1 mm) with a maximum value of 1 nW/mm3 and standard deviation of 1 mm. In the other setup, it is assumed that only one dorsal view of the animal can be obtained. There are 9 source fibers located on the ventral surface of the mouse as shown in Figure 3(c). There are 338 detectors consisting of 13 layers where each layer includes 26 detectors forming a field of view of 260° on the dorsal surface. It is assumed that the light fluence rate at all detectors can be obtained from CCD camera images by appropriate geometrical mapping (Silva et al 2009)

Figure 3.

(a) A 3D finite element mesh for the object used in the simulation. The mesh is a regular Delaunay tetrahedral with 17966 nodes and 99140 tetrahedrons generated by iso2mesh (Fang and Boas 2009). The object represents a section of a mouse abdomen which illustrates 5 different tissue regions: (1) adipose, (2) liver and spleen, (3) bowel, (4) kidneys, and (5) bone. (b) A schematic of the object showing the sources and detectors set up and the coordinate system. In this setup, 12 external sources are uniformly distributed around the object at 30° increments (one source of the 12 is shown in Figure 3(b)) and associated with each source are (13*30) detectors forming a 300 degree field of view. (c) This setup includes 9 optical fibers used as external sources located on the ventral surface of the mouse while the detectors are (13*26) and form a single field of view of 260 degrees on the dorsal surface.

The forward model, Equation (3), is used to simulate the measured data using the actual optical properties and 2% Gaussian noise is added to the calculated data to simulate realistic conditions. The true scattering and absorption coefficients were calculated using the data reported in (Alexandrakis et al 2005 and Prahl 2001) and are shown in Tables 1 and 2 respectively.

Table 1.

True (Alexandrakis et al 2005 and Prahl 2001) reduced scattering coefficients for each region in the heterogeneous object at five different wavelengths. The values of the scattering coefficients are given in (mm-1).

| 590 nm | 600 nm | 610 nm | 620 nm | 630nm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adipose | 1.29 | 1.28 | 1.27 | 1.26 | 1.25 |

| Liver | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.72 |

| Bowel | 1.35 | 1.32 | 1.29 | 1.27 | 1.24 |

| Kidney | 2.73 | 2.66 | 2.60 | 2.53 | 2.47 |

| Bone | 3.01 | 2.93 | 2.86 | 2.80 | 2.73 |

Table 2.

True (Alexandrakis et al 2005 and Prahl 2001) absorption coefficients for each region in the heterogeneous object at five different wavelengths. The values of the absorption coefficients are given in (mm-1).

| 590 nm | 600 nm | 610 nm | 620 nm | 630nm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adipose | 0.0043 | 0.0021 | 0.0014 | 0.0010 | 0.0008 |

| Liver | 0.3993 | 0.1899 | 0.1200 | 0.0824 | 0.0647 |

| Bowel | 0.0128 | 0.0063 | 0.0040 | 0.0028 | 0.0023 |

| Kidney | 0.0746 | 0.0356 | 0.0226 | 0.0156 | 0.0123 |

| Bone | 0.0670 | 0.0325 | 0.0207 | 0.0142 | 0.0112 |

In the first step, the Jacobian matrix is calculated at an initial guess of the scattering and absorption coefficients. The initial estimates used for scattering and absorption for all tissues at all wavelengths are 1 mm−1 and 0.01 mm−1 respectively. The advantage of the new method for calculating the Jacobian is that the time required is comparable to the time for the forward calculations. The calculation of derivatives of the light fluence rate with respect to the scattering and absorption coefficients at all nodes, as shown in Equation (11), requires the one-time calculation of A−1 and ϕ which needs a forward solver time in addition to the calculation of the matrix . Using Equations (9) and (10), the assembly matrix is obtained and the required simulation time is comparable to the simulation time to obtain the assembly matrix A and therefore a forward solver simulation time. The calculation of the Jacobian using the direct method proposed in the paper is much faster and more efficient than the traditional way of calculation through perturbing the optical properties at each node and calculating the change in the light fluence rate due to this perturbation as described in (Fedele et al 2003). This traditional direct method requires the call of the forward solver routine twice for each node of the FE mesh to calculate the derivatives. The minimization problem in Equation (20) is solved using the function “fmincon” of Matlab and the lower and upper limits of scattering and absorption coefficients used are 0.5 and 4 mm−1 and 0.0005 and 0.7 mm−1 respectively.

The DOT algorithm was applied to the object shown in Figure 3 using several different approaches. The objective is to compare the reconstructed scattering and absorption coefficients obtained and to assess the accuracy of the BLT reconstruction obtained using the optical properties obtained with each approach. First, the DOT results are obtained without segmentation which is the case when there is no information about different tissue types from, for example, a CT-scan. In this case, the DOT reconstruction is obtained locally in the region of interest, ROI as shown in Figure 4, while the rest of the object is assigned homogenous values for scattering and absorption. The ROI could be based on a priori biological information - for example, if the BL sources are expected to be in the kidneys, the DOT reconstruction is done in the abdomen while the rest of the body has a constant value for scattering and absorption. Auxiliary imaging methods like x-ray CT could help establish the location of the kidneys. In the absence of such knowledge, the raw bioluminescence images would provide enough information about the probable source location that an ROI could be determined. The values of the optical properties at regions away from the source location and the detectors locations do not have much effect on the BL signal. Therefore, restricting the DOT to be only in the region of interest will not affect the BLT results and at the same time give better resolution for the reconstructed optical properties in the region of interest as the number of unknowns becomes smaller and the solution can be obtained in less time. The solution starts using Equation (18) and assuming that for the first iteration all nodes have the same scattering and absorption so the equation will contain two variables: one for scattering and one for absorption. Solving the minimization problem will give the new values for scattering and absorption. These values will be assigned to all nodes outside the region of interest while, for the following iterations, improved values for scattering and absorption in the region of interest will be obtained.

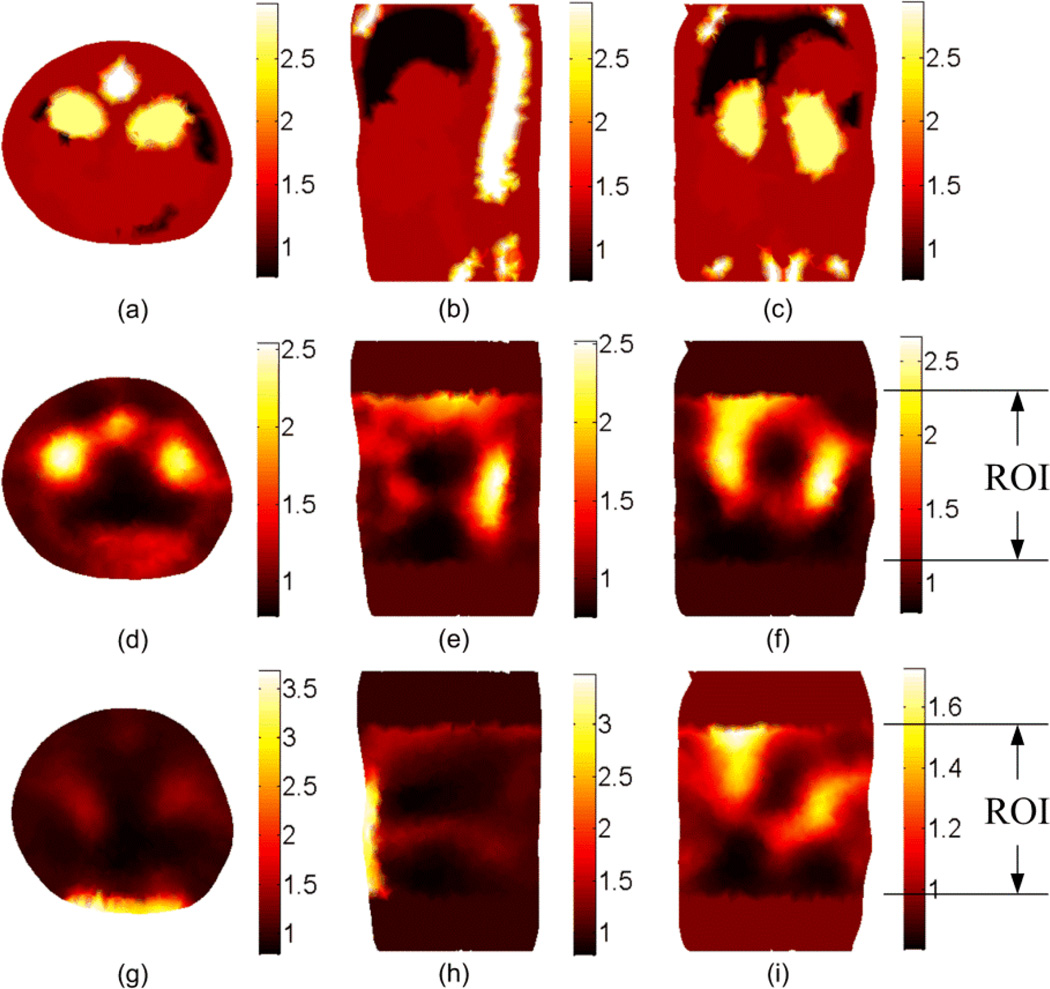

Figure 4.

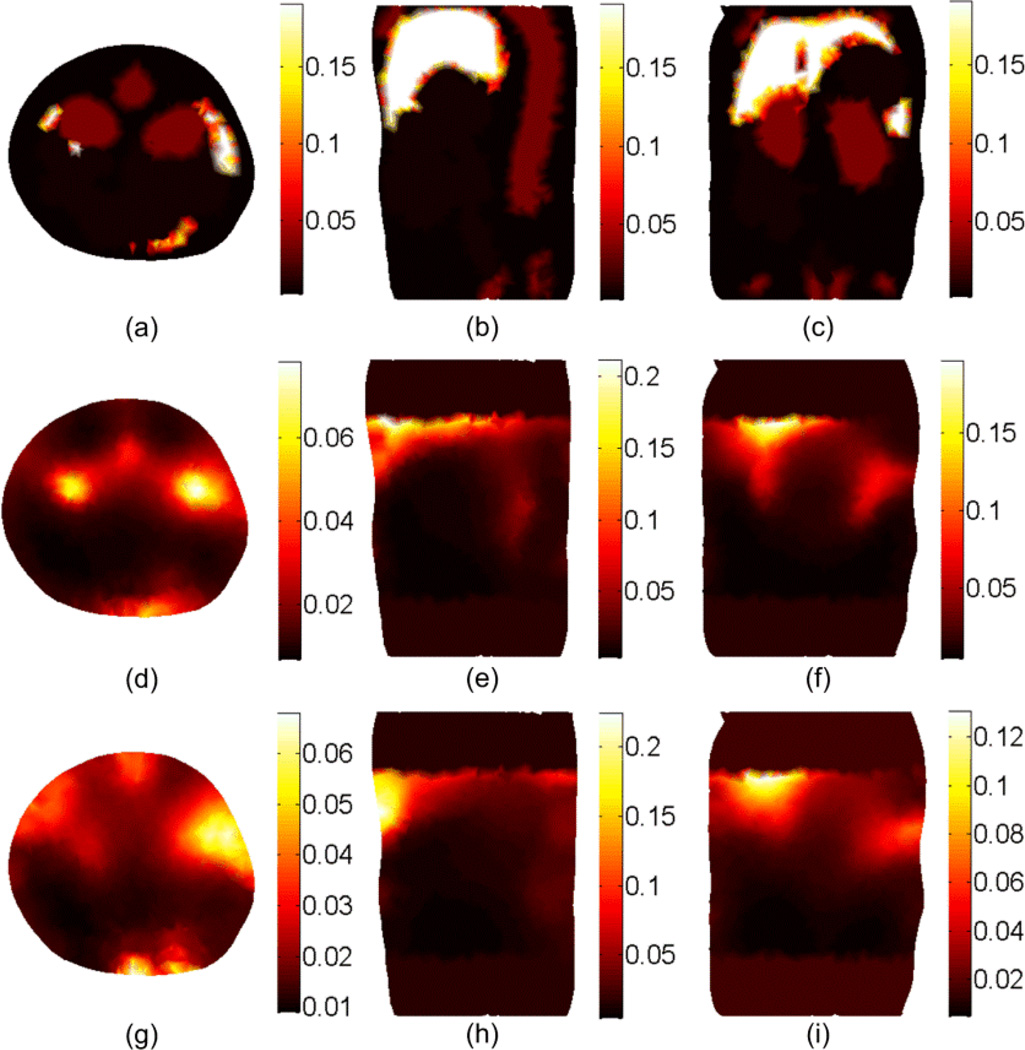

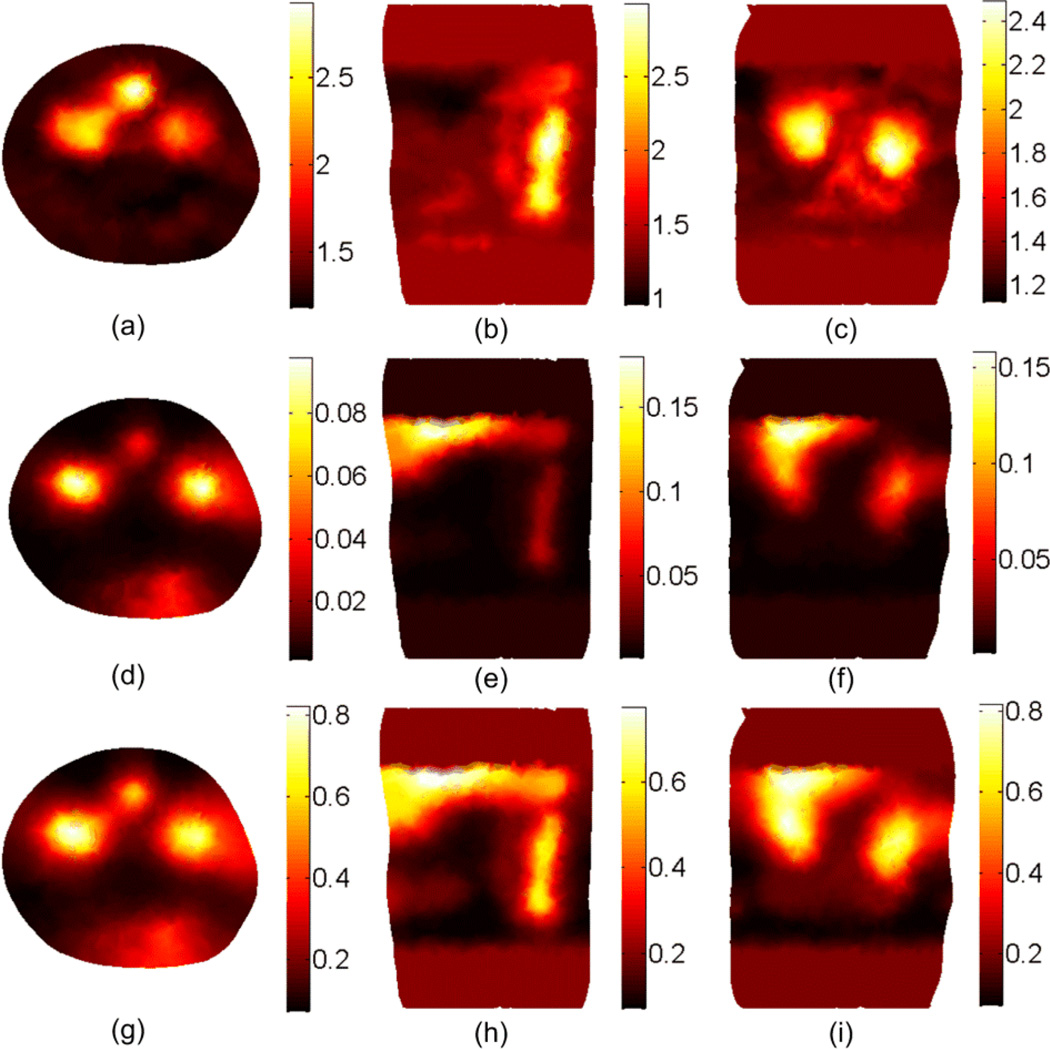

The DOT reconstruction results for the scattering coefficient at 600 nm. (a), (b), and (c) shows the cross, sagittal, and coronal sections of the actual scattering . The second and third rows show the reconstructed without segmentation using the setups shown in Figure 3(b) and Figure 3(c), respectively. The ROI is 20 mm in the z direction.

Figure 4 shows the DOT reconstruction results for the scattering coefficient without tissue segmentation. The first row shows the true scattering coefficients in three different cross-sections. The second and third rows show the reconstructed scattering coefficient using the setup shown in Figure 3(b) and 3(c) respectively. It is apparent that better resolution could be obtained using the setup in Figure 3(b) because more information about the object is available by multiple views. The results for the absorption coefficient and effective attenuation are shown in Figures 5 and 6 respectively. The number of iterations used to get the results shown in Figures 4 to 6 is 7 and each simulation took 20 minutes on a pc with Intel processor with a clock of 3.33 GHz and 24 GB RAM. Since the solution is not unique (which means different distributions for the scattering and absorption coefficients can produce the same light fluence rates at the detectors locations)no further iterations are performed when the calculated light fluence rate is within 5% of the "measured" value.

Figure 5.

The DOT reconstruction results for the absorption μa coefficient at 600 nm. (a), (b), and (c) shows the cross, sagittal, and coronal sections of the actual absorption μa. The second and third rows show the reconstructed μa without segmentation using the setup shown in Figure 3(b) and Figure 3(c), respectively.

Figure 6.

The DOT reconstruction results for the effective attenuation μeff coefficient at 600 nm. (a), (b), and (c) shows the cross, sagittal, and coronal sections of the actual μeff. The second and third rows show the reconstructed μeff without segmentation using the setup shown in Figure 3(b) and Figure 3(c), respectively.

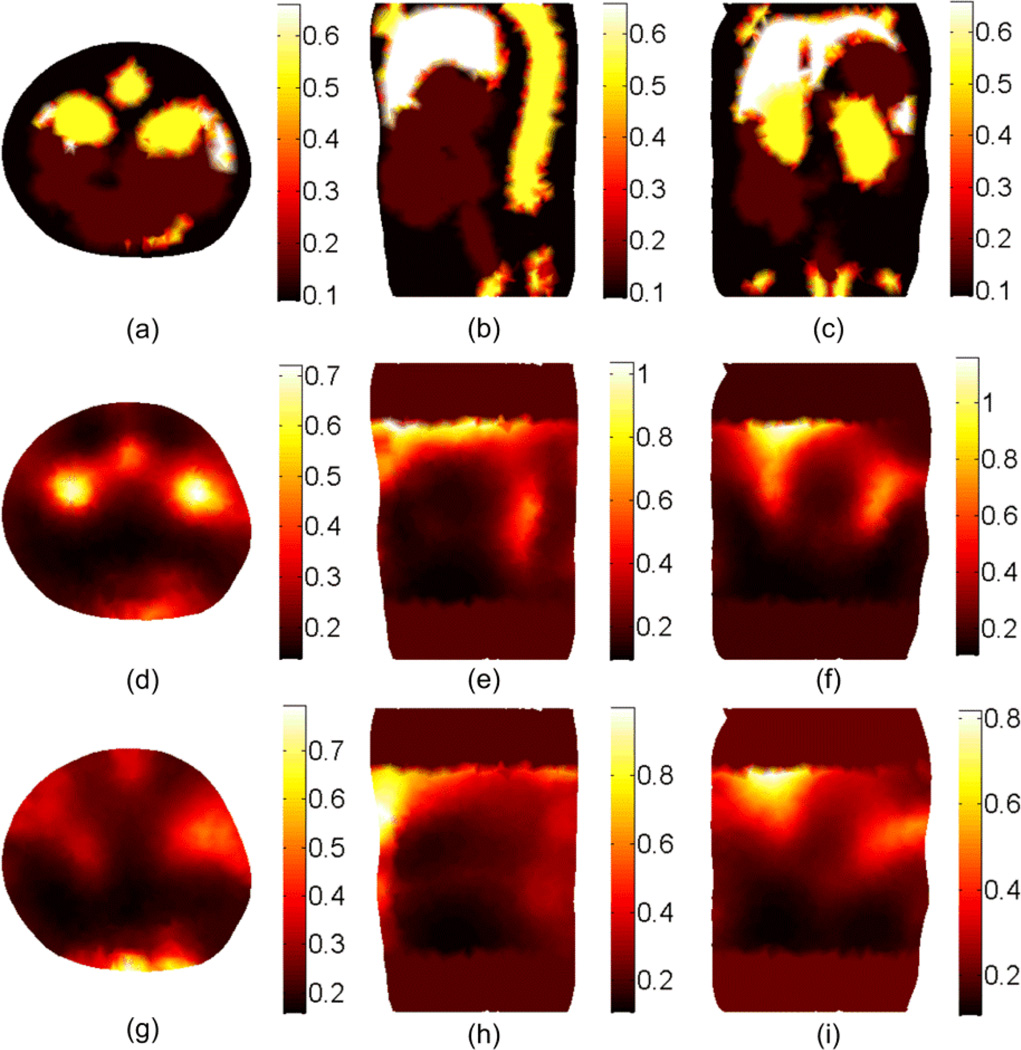

Figure 7.

The relative percent error in the reconstruction of scattering , absorption μa, and effective attenuation μeff, for the 5 tissues (1) adipose, (2) liver, (3) bowel, (4) kidney, and (5) bone at 600 nm using perfect segmentation. The results shown in the first row were obtained using the setup in Figure 3(b) while the results in the second row were obtained using the setup in Figure 3(c).

The second DOT approach assumes a perfectly segmented object. Using the information about different tissue types, the number of unknown optical properties is shrunk to be twice the number of tissue types or regions. Using Equation (18), the number of unknowns is 10 as there are 5 tissue types. Since the number of variables is small in this case, there is no need to consider a local region of interest for the DOT. Figure 7 shows the relative error in reconstructing the scattering, absorption, and effective attenuation coefficients for the 5 different tissues using the setup in Fig. 3(b) for the first row and the setup in Figure 3(c) for the second row. The maximum relative error is within 25% for scattering and absorption while the effective attenuation is reconstructed within 10%. Both setups show good results when perfect segmentation of the object is available. For 21 iterations, the simulation time was 10 minutes.

The third DOT approach uses an adaptive segmentation in which the solution from the previous iteration is used to shrink the number of unknowns by combining the nodes that have scattering or absorption values within a small domain. The first 7 iterations were used to obtain the results shown in Figures 4, 5, and 6 and then, by applying the algorithm in the flowchart in Figure 2 for another 14 iterations, the number of unknowns was reduced from 15694 to 40 (i.e. 20 regions).

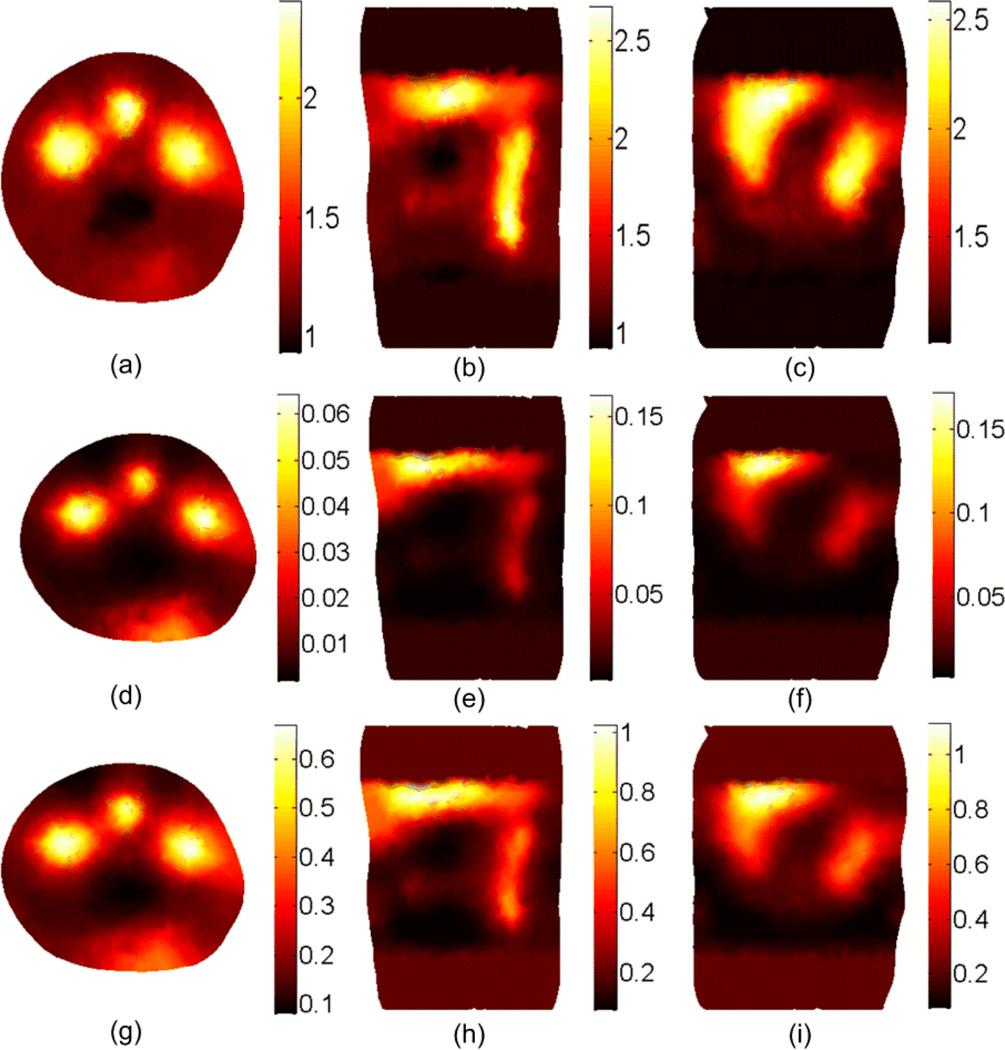

Figure 8 shows the DOT reconstruction results for the scattering, absorption, and effective attenuation coefficients using the adaptive segmentation method. The results were obtained using the setup in Figure 3(b) for the CW case (f = 0 Hz) and the simulation time for 21 iterations was 50 minutes. The figure shows better resolution compared to the non-segmented case in Figures 4, 5, and 6 and better contrast of different tissue types. To quantify the improvement in the image quality we define the normalized magnitude error (NME) as , where μ(i) is the optical coefficient at the element center, V(i) is the volume of the element i in the FE mesh, and the summation includes all elements of the mesh. The NME for scattering, absorption, and effective attenuation coefficients shown in Figure 8 are 0.21, 0.9, and 0.58 respectively while the corresponding values without segmentation for the coefficients shown in the second row of Figures 4, 5, and 6 are 0.28, 0.99, and 0.61. The part of the liver in the region of interest can still be identified using the effective attenuation coefficient. However, the solution still has degeneracy especially close to the top edge of the region of interest where we have the last row of detectors and a weak signal from the source.

Figure 8.

The DOT reconstruction results at 600 nm for the scattering at the first row, the absorption μa at the second row, and the effective attenuation μeff at the third row using the adaptive segmentation algorithm shown in Figure 2.

Figure 9 shows the DOT reconstruction results for the scattering, absorption, and effective attenuation coefficients using the adaptive segmentation method. For the frequency domain case (f = 100 MHz) the simulation time for 21 iterations was 75 minutes. The results are obtained using the setup in Figure 3(b) assuming that the modulation frequency of the excitation sources is 100 MHz and the light fluence rate phase information can be measured at the boundary. Since the amount of data is doubled by including both magnitude and phase of the light fluence rate, better reconstruction results can be obtained compared to the CW case in Figure 8. As can be noticed for the coronal section in Figure 9(c), the localization of the two kidneys is better than in the CW case. In addition, the reduced degeneracy of the solution results in better reconstruction of the scattering and absorption of the liver close to the top edge of the permissible region. The NME for scattering, absorption, and effective attenuation coefficients is 0.13, 0.86, and 0.51 respectively.

Figure 9.

The DOT reconstruction results at 600 nm for the scattering at the first row, the absorption μa at the second row, and the effective attenuation μeff at the third row using the adaptive segmentation algorithm shown in Figure 2 and using external sources modulation frequency of 100 MHz.

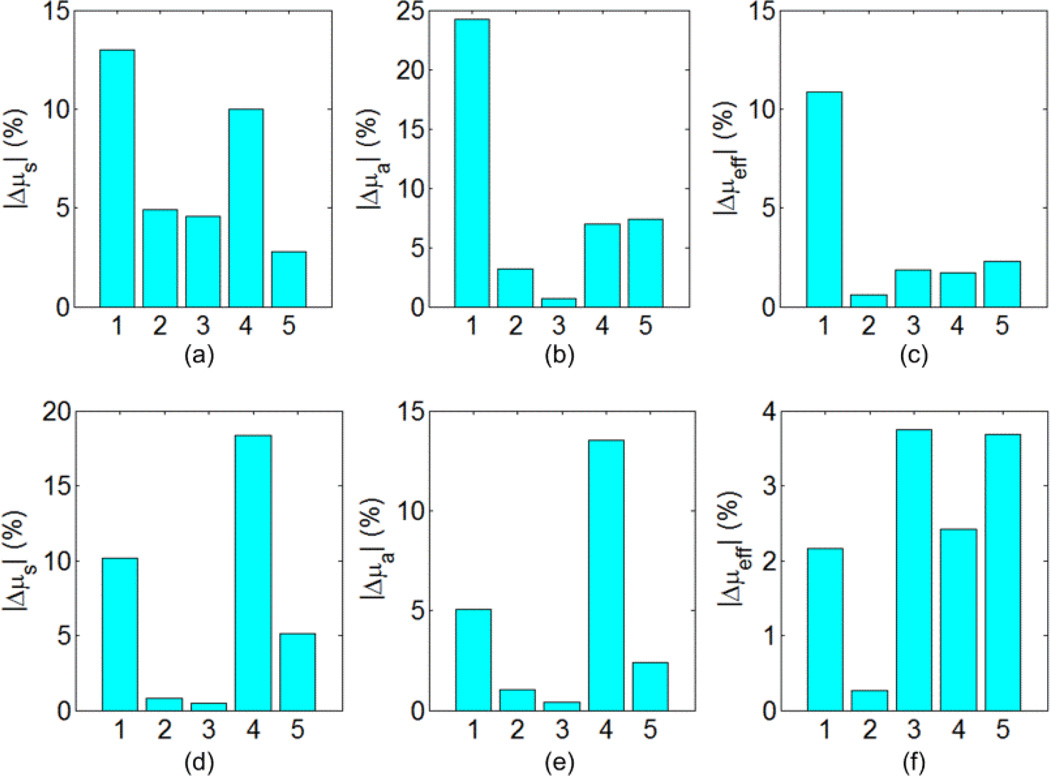

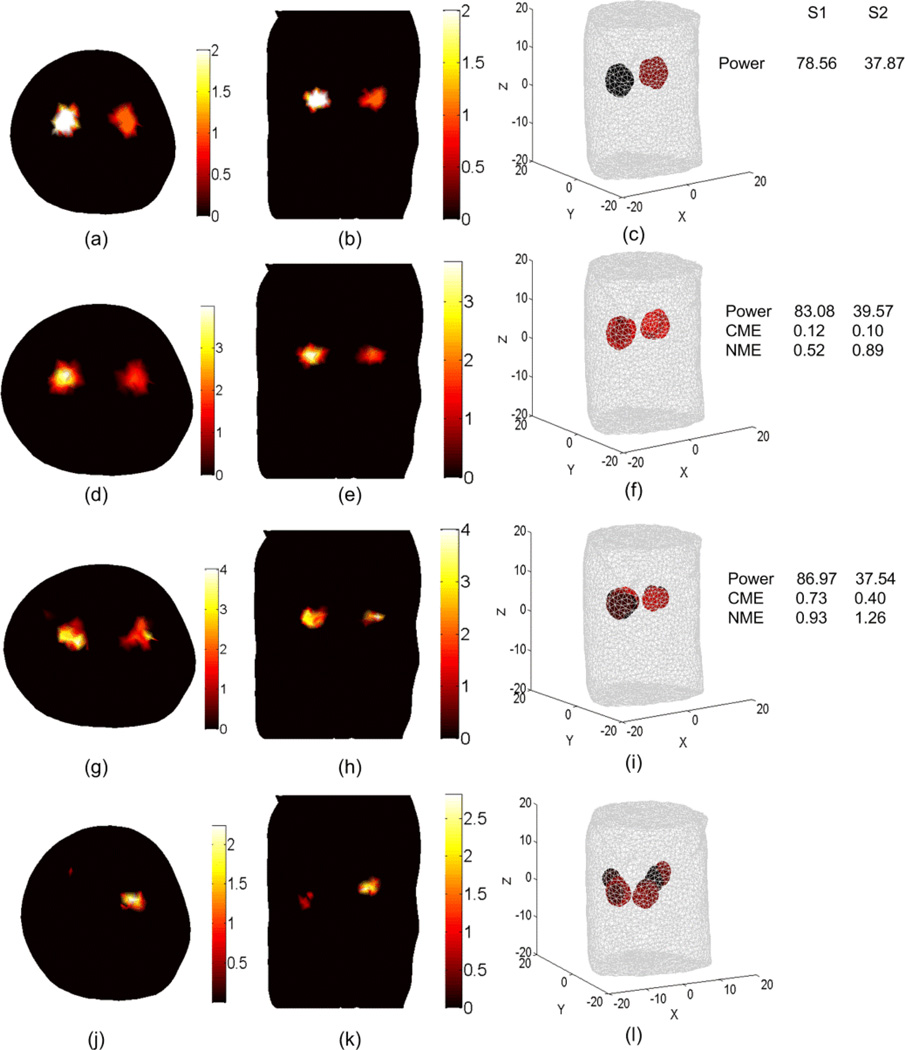

The BLT results shown in Figures 10 and 11 are obtained using our BLT algorithm which is based on eigenvector decomposition and adaptive shrinking of the permissible source region (Naser et al 2012 and Naser and Patterson 2011). The spectrally resolved data at 5 wavelengths were used along with optimized selection of the permissible source region. Figure 10 shows the BLT reconstruction for two uniform bioluminescence sources localized in the left and right kidneys (4 mm diameters). The source-detectors setup used for the DOT and BLT is shown in Figure 3(c). The first row shows the actual BL source distributions and the total power of the two sources. The other rows show the reconstructed sources using the optical properties estimated by different DOT approaches. The accuracy of the reconstructed source is affected by the mesh element size. In the forward calculations for both DOT and BLT, it is assumed that within each element of the FE mesh, the optical properties and the source magnitude do not change. Therefore, the best accuracy that can be obtained will be within the average element size of the mesh. Decreasing the mesh element size can improve the accuracy, but increasing the number of mesh nodes will increase the computation time. The computation time of the forward calculations as a function of the number of the FE mesh nodes is approximately proportional to N2, where N is the number of mesh nodes. The reconstructed source powers, the center of mass error (CME) in mm, and the normalized magnitude error (NME, see below for definition) are shown to the right of the figure. These objective metrics have been calculated to assess the accuracy of the BLT reconstruction of each source. The first is simply the total power integrated over three dimensions, , where s(i) is the source value at the element center, V(i) is the volume of the element i in the FE mesh, and the summation includes all elements that include the source. The second metric is the "center of mass error" which is the distance between the center of mass of the actual and reconstructed sources. The center of mass of the source is defined as where C(i) is the element center (x, y, z coordinates). The third we define as the “normalized magnitude error” calculated according to . This element-by-element summation is sensitive to the shape and position of the reconstructed source and is a more stringent metric than the total power - smaller values mean better reconstruction results. Comparing the BLT results of the second and third row shows that using the DOT of a perfectly segmented object gives better BLT reconstruction in terms of the source reconstructed power, the location of the center of mass, and the magnitude. However, the results for the non-segmented object still show good reconstructed total source power. It requires only a simple optical setup to do the DOT and BLT and there is no need of another imaging modality such as x-ray CT or MRI. The last row shows the importance of DOT as the BLT is poor if the object is assumed to be homogenous (i.e. one value for scattering and absorption coefficient is assigned to all tissues) which is done by setting the number of regions to 1 in Equation (18). The second and third row show that the DOT is required for only for the region of interest around the sources and not for the whole object, which makes the number of unknowns smaller and the solution faster. Although not shown here, the adaptive segmentation algorithm for DOT did not lead to a better BLT solution in this case even though the DOT solution itself was more accurate.

Figure 10.

BLT reconstruction of two uniform bioluminescence sources localized in the left and right kidneys (4 mm diameters). The “anatomy” is shown in Figure 3. The actual sources in transverse section (a), coronal section (b), and 3D view (c) have magnitudes 2 nW/ mm3 and 1 nW/ mm3 for the left and right source respectively. The source-detectors setup used for the DOT and BLT is as shown in Figure 3(c) where one view of a 260 degree field of view is used. The reconstructed sources are shown in (d), (e), and (f) using the DOT results shown in Figure 7 (a), (b), and (c) where segmentation using CT-scan is used. The BLT results shown in (g), (h), and (i) are obtained using unsegmented DOT results shown in Figs 4 and 5 third row. The BLT results shown in (j), (k), and (l) are obtained using DOT results assuming homogenous optical properties where there is only one scattering and absorption coefficients used for all tissues.

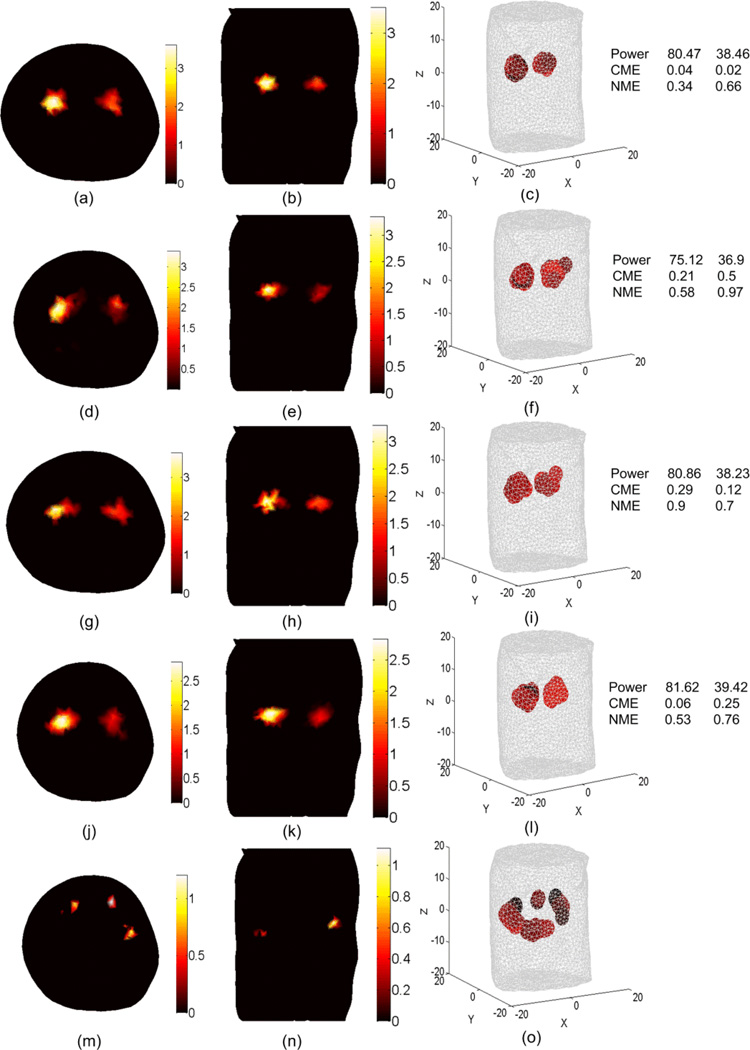

Figure 11.

BLT reconstruction of two uniform bioluminescence sources where the actual sources are the same as shown in the first row of Figure 10. The source-detectors setup used for the DOT and BLT is as shown in Figure 3(b) where 12 views with 300 degree field of view for each view is used for the DOT and 360 degree field of view used for the BLT. The reconstructed sources are shown in (a), (b), and (c) using the DOT results shown in Figure 7 (d), (e), and (f) where segmentation using CT-scan is used. The reconstructed sources are shown in (d), (e), and (f) using the non-segmented object DOT results shown in the second row of Figures 4 and 5. (g), (h), and (i) show the BLT results where adaptive segmented object DOT results, shown in Figure 8, with (f = 0 Hz) used. (j), (k), and (l) show the BLT results where adaptive segmented object DOT results, shown in Figure 9, with (f = 100 MHz) used. (m), (n), and (o) show the BLT results where homogenous object DOT results used.

Figure 11 shows the BLT results when using the source-detectors setup shown in Figure 3(b) for the DOT. The same detectors are used for the BLT. The last row shows poor BLT reconstruction which indicates that using homogenous values for scattering and absorption does not give good BLT results. The results of the first 4 rows correspond to DOT for a perfectly segmented object, a non-segmented object, an adaptive segmented object CW, and an adaptive segmented object (f = 100 MHz). The reconstructed source powers using all four DOT approaches are within 5% of the true values. The advantage of using a segmented object is more accurate center of mass reconstruction and lower normalized magnitude error. Overall, the performance of the DOT approaches can be ranked as perfect segmentation (cw) > adaptive segmentation (100 MHz) > adaptive segmentation (cw) > no segmentation (cw)> homogenous (cw).

5. Conclusions

A localized DOT algorithm based on the finite element solution of the diffusion equation has been developed. The algorithm reconstructs the optical properties in a permissible domain or a region of interest where the BL sources are likely to exist. The Jacobian matrix is calculated using the direct method in an efficient way such that the derivatives at all nodes are calculated during the formation of the assembly matrix of the forward solver. The simulation time required is slightly more than twice the simulation time required for a forward calculation. The algorithm has been applied to simulations based on a highly detailed anatomy for a laboratory mouse (MOBY). Different approaches for DOT have been examined including no a priori information, perfect segmentation, and adaptive segmentation. Our previously developed BLT algorithm has been used to evaluate the quality of the BLT reconstruction using optical properties reconstructed by the different DOT approaches. The reconstructed total powers of the BL sources are comparable for perfect segmentation, adaptive segmentation, and no segmentation DOT. However, in terms of the reconstructed source center of mass and source magnitude, perfect segmentation shows better performance. For example, when using 360° field of view, the maximum error in the center of mass when using perfect segmentation (cw) is 0.04 mm, while the errors are 0.5, 0.29, and 0.25 mm for no segmentation (cw), adaptive segmentation (cw), and adaptive segmentation (100 MHz) respectively. Concerning the computational cost, no segmentation and adaptive segmentation have almost the same cost for the same number of iterations, however, the adaptive segmentation requires more iterations to reduce the number of regions, so the computation requires an order of magnitude more time than the no segmentation case. The computation cost of perfect segmentation is lower than the no segmentation case, as the number of unknowns is small, however the requirement of an auxiliary imaging method like CT will increase the total time requirement and the complexity of the instrumentation. Overall, for practical use, the non-segmented (cw) DOT approach is recommended for BLT as it leads to acceptable total power reconstruction and it does not require an auxiliary imaging method like x-ray CT. If more accuracy is required for the source magnitude and center of mass, perfect segmentation DOT is recommended as the adaptive segmentation for both cw and (100 MHz) are costly and do not provide much improvement over the non-segmented case. The adaptive segmentation DOT cw and FD show higher resolution and better contrast for the reconstructed optical properties compared to the non-segmented DOT. If the main objective is get improved DOT results and not BLT, the adaptive segmentation can provide better DOT results over the non-segmented DOT if an auxiliary imaging like CT is not available.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant RO1 CA158100.

Appendix

For the FE mesh, if the coordinates of all nodes are stored in the matrix nodes and the index of nodes for all tetrahedron elements are stored in the matrix t, the coordinates of the 4 nodes of the element l are given by

| Equation 22 |

The constant matrices and in Equation (7) are given by (Volakis et al 1998)

| Equation 23 |

and

| Equation 24 |

where the element volume Vl and the constants b, c, and d are given by

| Equation 25 |

| Equation 26 |

References

- Ahn S, Chaudhari AJ, Darvas F, Bouman CA, Leahy RM. Fast iterative image reconstruction methods for fully 3D multispectral bioluminescence tomography. Phys. Med. Biol. 2008;53:3921–3942. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/14/013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrakis G, Rannou FR, Chatziioannou AF. Tomographic bioluminescence imaging by use of a combined optical-PET (OPET) system: a computer simulation feasibility study. Phys. Med. Biol. 2005;50:4225–4241. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/17/021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arridge SR. Optical tomography in medical imaging. Inverse Problems. 1999;15:41–93. [Google Scholar]

- Arridge SR, Schweiger M, Hiraoka M, Delpy DT. A finite element approach for modeling photon transport in tissue. Med. Phys. 1993;20:299–309. doi: 10.1118/1.597069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao N, Nehorai A, Jacobs M. Image reconstruction for diffuse optical tomography using sparsity regularization and expectation-maximization algorithm. Opt. Express. 2007;15(21):13695–13708. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.013695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhari AJ, Darvas F, Bading JR, Moats RA, Conti PS, Smith DJ, Cherry SR, Leahy RM. Hyperspectral and multispectral bioluminescence optical tomography for small animal imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 2005;50:5421–5441. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/23/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Gao X, Chen D, Ma X, Zhao X, Shen M, Li X, Qu X, Liang J, Ripoll J, Tian J. 3D reconstruction of light flux distribution on arbitrary surfaces from 2D multi-photographic images. Optics Express. 2010;18(19):19876–19893. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.019876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comsa DC, Farrell TJ, Patterson MS. Quantification of bioluminescence images of point source objects using diffusion theory models. Phys. Med. Biol. 2006;51:3733–3746. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/15/009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong W, Wang G, Kumar D, Liu Y, Jiang M, Wang LV, Hoffman EA, McLennan G, McCray PB, Zabner J, Cong A. Practical reconstruction method for bioluminescence tomography. Opt. Express. 2005;13:6756–6771. doi: 10.1364/opex.13.006756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani H, Davis SC, Jiang S, Pogue BW, Paulsen KD, Patterson MS. Spectrally resolved bioluminescence optical tomography. Opt. Lett. 2006;31:365–367. doi: 10.1364/ol.31.000365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani H, Eames ME, Yalavarthy PK, Davis SC, Srinivasan S, Carpenter CM, Pogue BW, Paulsen KD. Near infrared optical tomography using NIRFAST: Algorithm for numerical model and image reconstruction. Commun. Numer. Methods Eng. 2008;25(6):711–732. doi: 10.1002/cnm.1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Q, Boas D. Tetrahedral mesh generation from volumetric binary and gray-scale images. Proceedings of IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging. 2009;2009:1142–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Fedele F, Laible JP, Eppstein MJ. Coupled complex adjoint sensitivities for frequency-domain fluorescence tomography: theory and vectorized implementation. Journal of Computational Physics. 2003;187:597–619. [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Jia K, Yan G, Zhu S, Qin C, Lv Y, Tian J. An optimal permissible source region strategy for multispectral bioluminescence tomography. Opt. Express. 2008;16:15640–15654. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.015640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Zhang Q, Larcom L, Jiang H. Three-dimensional bioluminescence tomography with model-based Reconstruction. Opt. Express. 2004;12:3996–4000. doi: 10.1364/opex.12.003996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Liang J, Qu X, Huang H, Hou Y, Tian J. Truncated total least squares method with a practical truncation parameter choice scheme for bioluminescence tomography inverse problem. Int. J. Biomed. Imaging. 2010;2010:291874-11. doi: 10.1155/2010/291874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Qu X, Liang J, He X, Chen X, Yang D, Tian J. A multi-phase level set framework for source reconstruction in bioluminescence tomography. J. Comput. Phys. 2010;229:5246–5256. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H. Frequency-domain fluorescent diffusion tomography: a finite-element-based algorithm and simulations. Appl. Opt. 1998;37:5337–5343. doi: 10.1364/ao.37.005337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose AD. Transport-theory-based stochastic image reconstruction of bioluminescence sources. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A. 2007;24:1601–1608. doi: 10.1364/josaa.24.001601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C, Coquoz O, Troy TL, Xu H, Rice BW. Three-dimensional reconstruction of in vivo bioluminescent sources based on multispectral imaging. J. Biomed. Opt. 2007;12:024007. doi: 10.1117/1.2717898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Zhang X, Douraghy A, Stout D, Tian J, Chan TF, Chatziioannou AF. Source Reconstruction for Spectrally-resolved Bioluminescence Tomography with Sparse a priori Information. Opt. Express. 2009;17(10):8062–8080. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.008062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchuk GI. Adjoint Equations and Analysis of Complex Systems. The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Marchuk GI, Agoshkov VI, Shutyaev VP. Adjoint Equations and Perturbation Algorithms in Nonlinear Problems. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mohajerani P, Eftekhar AA, Huang J, Adibi A. Optimal sparse solution for fluorescent diffuse optical tomography: theory and phantom experimental results. Appl. Opt. 2007;46(10):1679–1685. doi: 10.1364/ao.46.001679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naser MA, Patterson MS. Algorithms for bioluminescence tomography incorporating anatomical information and reconstruction of tissue optical properties. Biomed. Opt. Express. 2010;1:512–526. doi: 10.1364/BOE.1.000512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naser MA, Patterson MS. Improved bioluminescence and fluorescence reconstruction algorithms using diffuse optical tomography, normalized data, and optimized selection of the permissible source region. Biomed. Opt. Express. 2011;2:169–184. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.000169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naser MA, Patterson MS. Bioluminescence tomography using eigenvectors expansion and iterative solution for the optimized permissible source region. Biomed. Opt. Express. 2011;2:3179–3193. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.003179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naser MA, Patterson MS, Wong JW. Self-calibrated algorithms for diffuse optical tomography and bioluminescence tomography using relative transmission images. Biomed. Opt. Express. 2012;3(11):2794–2808. doi: 10.1364/BOE.3.002794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ntziachristos V, Ripoll J, Wang LV, Weissleder R. Looking and listening to light: the evolution of whole-body photonic imaging. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23(3):313–320. doi: 10.1038/nbt1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prahl SA. http://omlc.ogi.edu/spectra/index.html (Oregon Medical Laser Clinic) 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Schweiger M, Arridge SR, Hiraoka M, Delpy DT. The finite element method for the propagation of light in scattering media: boundary and source conditions. Med. Phys. 1995;22:1779–1792. doi: 10.1118/1.597634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segars WP, Tsui BM, Frey EC, Johnson GA, Berr SS. Development of a 4-D digital mouse phantom for molecular imaging research. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2004;6(3):149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.mibio.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva A, Leabad M, Driol C, Bordy T, Debourdeau M, Dinten J, Peltié P, Rizo P. Optical calibration protocol for an x-ray and optical multimodality tomography system dedicated to small-animal examination. Applied Optics. 2009;48(10):D151–D162. doi: 10.1364/ao.48.00d151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavine NV, Lewis MA, Richer E, Antich PP. Iterative reconstruction method for light emitting sources based on the diffusion equation. Med. Phys. 2006;33:61–68. doi: 10.1118/1.2138007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J, Bai J, Yan XP, Bao S, Li Y, Liang W, Yang X. Multimodality molecular imaging. IEEE Eng.Med. Biol. Mag. 2008;27(5):48–57. doi: 10.1109/MEMB.2008.923962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volakis LJ, Chatterjee A, Kempel LC. Finite Element Method for Electromagnetics. New York: IEEE Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Weissleder R, Mahmood U. Molecular imaging. Radiology. 2001;219(2):316–333. doi: 10.1148/radiology.219.2.r01ma19316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmann JK, Bruggen NV, Dinkelborg LM, Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging in drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008;7(7):591–607. doi: 10.1038/nrd2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalavarthy PK, Pogue BW, Dehghani H, Paulsen KD. Weight-matrix structured regularization provides optimal generalized least-squares estimate in diffuse optical tomography. Med. Phys. 2007;34:2085–2098. doi: 10.1118/1.2733803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]