Abstract

Streptomyces phage φC31 integrase induces efficient site-specific recombination capable of integrating exogenous genes at pseudo attP sites in human, mouse, rat, rabbit, sheep, Drosophila, and bovine genomes. However, the φC31-mediated recombination between attB and the corresponding pseudo attP sites has not been investigated in Capra hircus. Here, we identified eight pseudo attP sites located in the intron or intergenic regions of the C. hircus genome, and demonstrated different levels of foreign gene expression after φC31 integrase-mediated integration. These pseudo attP sites share similar sequences with each other and with pseudo attP sites in other mammalian genomes, and these are associated with a neighboring consensus motif found in other genomes. The application of the φC31 integrase system in C. hircus provides a new option for genetic engineering of this economically important goat species.

Introduction

In nature, the phage φC31 integrase recombines an attP site in the phage genome with a chromosomal attB site of its Streptomyces host (Andreas et al., 2002). Mammalian genomes were found to contain “pseudo” attP sites, which have partial sequence identity to the phage attP site and can also mediate efficient integrase activity (Thyagarajan et al., 2001). Compared with other recombination systems such as Cre and FLP, φC31 integrase has advantages of efficiency, unidirectional integration, no cofactor requirements, high levels of long-term transgene expression, and no insert size limitations (Thorpe and Smith, 1998; Calos, 2006). Therefore, the phage φC31 integrase has great potential for genetic modification. While the φC31 integrase has been proved to be functional in the human, mouse, rat, rabbit, bovine, sheep, Drosophila, and zebrafish genomes (Olivares et al., 2002; Groth et al., 2004; Chalberg et al., 2005, 2006; Ma et al., 2006; Ehrhardt et al., 2007; Lu et al., 2010; Ni et al., 2012), it is unclear whether this enzyme can induce efficient site-specific recombination in Capra hircus fibroblast cells. Here, we show that functional “pseudo” attP sites exist in the C. hircus genome.

The use of φC31 integrase-mediated genetic engineering has many potential important applications, the mammary gland bioreactor, for example. The lack of C. hircus embryonic stem (ES) cells has limited the production of mammary gland bioreactor by gene targeting in C. hircus, but somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) technology has provided another useful mean. Using φC31 integrase, pseudo-attP site-directed integration in C. hircus fibroblast cell (the common donor cell for SCNT), can be performed for foreign genes chosen at a high expression level. The φC31 integrase system had been used for the engineering of human and mouse ES cells (Belteki et al., 2003; Thyagarajan et al., 2008), it could also prove to be useful for genome modification and transgenic research in the C. hircus and its ES cells once these cells became available.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All goats used in this study were obtained from the Experimental Animal Farm (Institute of Medical Genetics, Shanghai Children's Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University). All experiments in this study were conducted as procedures approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee, Shanghai Children's Hospital (Shanghai, China).

Int-φC31 activity assay plasmids

Plasmid pCMV-Int for expression of the integrase in mammalian cells was supplied by Dr. M.P. Calos of Stanford University (Groth et al., 2000). The attB sequence was from pBCPB (provided by Dr. M. P. Calos) and cloned into the AflII site of pEGFP-N1 to create the plasmid pEGFP-N1-attB, which contained the transgenic green fluorescent protein as reporter and the neomycin resistant gene (Ma et al., 2006). Plasmid pcDNA3.1-zeo was obtained from Invitrogen.

C. hircus primary fibroblast cells

Here, the C. hircus fibroblast cell, the common donor cell for nuclear transfer (Wilmut et al., 2002), was chosen for our experiments. Primary fibroblast cells were obtained from a 3-month-old goat at Songjiang Experimental Animal Facility, affiliated with the Institute of Medical Genetics of Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China. After washing thrice with phosphate-buffered saline containing 50 U/mL of penicillin and 5 mg/mL streptomycin (Gibco BRL), ear tissue was clipped into 2 mm2 pieces. Fat tissue was removed and tissue samples were explanted to 25 cm2 culture flask with 0.5 mL glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/F12 (Gibco BRL) containing 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone), 50 U/mL of penicillin, and 50 mg/mL streptomycin. After culturing at 37.5°C for 24 h in inverted dishes to prevent cell adherence, 4.0 mL fresh DMEM/F12 was added to reoriented dishes for adherent explant culture. About 10 days later the cells reached 80% confluence and were collected by trypsinization.

Cell culture and transfection

The collected fibroblast cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 containing 10% fetal bovine serum to 90% confluence. The cells were co-transfected with lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) using 0.1 μg pEGFP-N1-attB and 1 μg pCMV-Int plasmids. The mixtures of expression vector DNA and lipofectamine 2000 were added to the medium over the cells and incubated for 8 h. After culturing in fresh growth medium for 48 h, transfected cells were selected by growth for 12–15 days in medium containing 500 μg/mL of G418 (Gibco BRL) until resistant colonies were formed. The colonies were separately picked after digesting with trypsin and removed to six-well plates, each colony was cultured in one individual well in growth medium containing 200 μg/mL of G418 for 2–3 days before analysis.

To examine the integration efficiency of φC31 integrase, we co-transfected different ratios of the pEGFP-N1-attB vector and the integrase plasmid (pCMV-Int) into the fibroblast cells in six-well plates. Fibroblast cells in each well were transfected with 0.1 μg pEGFP-N1-attB plasmid and different mounts of integrase plasmid. The amounts of integrase plasmid are listed in Figure 2. To assure that the amount of total transfected DNA was equal in each well, the blank plasmid pcDNA3.1-zeo (Invitrogen) was included. Transfection and selection were performed as described above. The colonies formed by different mounts of integrase were numbered under the microscopy.

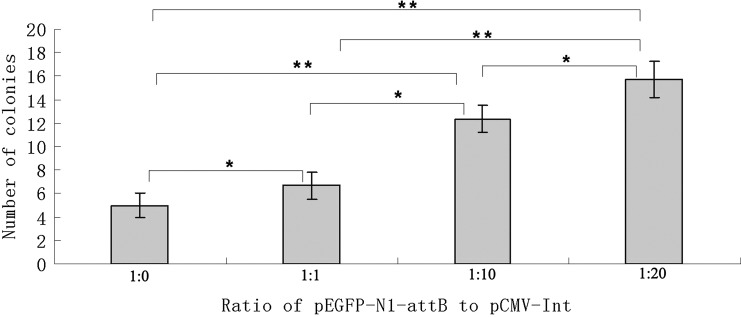

FIG. 2.

Integration rates in C. hircus fibroblast cells. The data are indicated as mean±standard deviation from three experiments. Significant difference at *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 by t-test.

Flow cytometric analysis of the GFP expression

Cells of each GFP+ colony were trypsinized, washed, and resuspended at the desired concentration in a volume of 0.5 mL. About 1×105 cells from each sample were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur and FACSVantage SE; Becton Dickinson).

PCR assay to identify attB site disruption

Genomic DNA was isolated from the co-transfected cells by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Since φC31 integrase-mediated site-specific integration between attB and pseudo attP sites results in breakage of the attB site, PCR amplification with primers A (CCCCTGAACCTGAAACAT) and D (CAACACTCAACCCTATCTCG), which were located in the plasmid backbone upstream and downstream of the attB sequence, respectively, will fail to produce an amplicon. PCR was performed as follows: 1 cycle of 94°C for 5 min; 31 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 45 s; followed by 72°C for 10 min. Amplification of the GAPDH gene with primers GAPDH-F (GTCGGAGTGAACGGATTCG) and GAPDH-R (AGTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTGAT) was performed as internal control using the same PCR conditions except with 56°C annealing. PCR products were visualized by gel electrophoresis on 2% agrose gel.

Reverse PCR assay

Pseudo attP sites were mapped in the C. hircus genome using reverse PCR. Briefly, 10 μg of genomic DNA from transfected colonies were digested with 60 U HindIII (NEB) for 16 h. Intra-fragment circularization was performed by self-ligation with 2000 U T4 DNA ligase (NEB) in 200 μL at 16°C overnight, followed by phenol-chloroform extraction, ethanol precipitation, and redissolving in 20 μL Tris-EDTA buffer. The reverse PCR amplifications across the integration junctions were conducted using long PCR (TaKaRa LA PCR Kit). The forward primer was GFP-F (CCCTGAACCTGAAACATAAA), and the reverse primer was GFP-R (TCACCTTGATGCCGTTCTT). The location of the primers is shown in Figure 1. The expected distance from the HindIII site in an integrated GFP gene to the adjunction site is 974 bp, so bands longer than 1 kb obtained from the reverse PCR may contain the genomic DNA adjacent to the pseudo attP integration site (Qu et al., 2012). These bands were purified using the Gel Purification Kit (Biomiga) and directly sequenced using the primer GFP-F. The sequences (about 100–200 bp) around breakpoint were compared with wild attP sequence (39 bp) by DNAMAN (by Lynnon Biosoft). The comparison of these sequences in the region of the crossover point with that of attP allowed evaluation of the level of identity, and the level of identity of the mammalian pseudo attP sites versus wild-type attP was 23–56%, and this was used as the reference (Thyagarajan et al., 2001; Olivares et al., 2002; Groth et al., 2004; Ma et al., 2006).

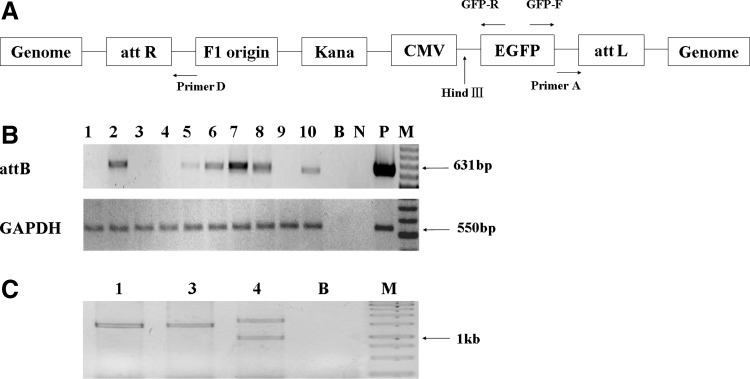

FIG. 1.

φC31 integrase-mediated recombination between transgenic attB and pseudo attP sites in the Capra hircus genome. (A) The transgene construct map is diagrammed as it would appear after integration into the C. hircus genome by φC31 integrase. (B) After PCR with primers A and D, a 631-bp amplicon specific for intact attB will be produced in non-integrase mediated colonies. Lanes 1–10 are amplicons of DNA from transgenic colonies; B, no-template control; N, negative control (goat genomic DNA was taken as negative control for amplification of attB, plasmid pEGFP-N1-attB served as negative control for amplification of GAPDH); P, positive control; M, 100 bp marker. (C) Reverse PCR with primers GFP-F and GFP-R after HindIII digestion and intra-fragment ligation will amplify flanking genomic sequences from circularized templates. Lanes 1, 2, and 3 show amplification products longer than 1000 bp from independent insertion events in cell colonies 1, 3, and 4 in the upper figure; B, blank control; M, 1 kb marker.

Bioinformatic analysis

The genomic locations of these genomic DNA sequences nearby the integration sites were determined by BLAST with the C. hircus genome databases (http://goat.kiz.ac.cn/GGD/). To characterize the pseudo attP sites in C. hircus and other species, we used MEME/MAST bioinformatics tools to analyze features of φC31 integrase-mediated transgene integration sites, with the aim of identifying a statistically siginificant sequence motif. As a control, eight random sequences from goat genome were individually computer-generated and a similar analysis was performed.

To make sure whether the pseudo attP sequences share similar motif in C. hircus and other species, we collected 97 pseudo attP sequences from the literature. According to the published data (Groth et al., 2004; Chalberg et al., 2005, 2006; Keravala et al., 2006; Ma et al., 2006; Ehrhardt et al., 2007; Qu et al., 2012), the sequences we retrieved around the pseudo attP sites were about 200 bp. As a control, 97 random sequences corresponding to these species were similarly analyzed by motif finder software. These sequences were processed using MEME (http://meme.sdsc.edu/meme/intro.html, National Biomedical Computation Resource).

Results

C. hircus genome contains pseudo attP sites

The fibroblast cells were transfected with pCMV-Int and pEGFP-N1-attB and selected by G418 for 2 weeks. The G418-resistant colonies were picked up and the genomic DNA of these colonies was extracted. Recombination between an attB site and a pseudo attP site mediated by φC31 integrase results in disruption of the attB sequence. To rule out transgene insertions not due to φC31 integrase, amplifications specific for intact attB in the genomic DNA of G418-resistant colonies were performed as shown in Figure 1. The production of a 631-bp amplicon would indicate intact attB sequences, and therefore the integration was not mediated by φC31 integrase. Ten colonies with transgene integration but no 631 bp amplicon were identified.

Reverse PCR of circularized genomic DNA fragments was used to amplify and sequence regions flanking the transgene insertion sites. The fragment sequences were aligned by BLAST with vector and C. hircus genomic maps, and recombination junctions were identified for the 10 colonies (Table 2). The sequences of about 100–200 bp around the breakpoint were compared to that from wild attP sequence (39 bp) by the DNAMAN soft (by Lynnon Biosoft). Eight sites were identified in the C. hircus genome, and identity to the wild attP sequence was 26–49%, similar to the level of identity in mammalian pseudo attP sites that had been isolated (Thyagarajan et al., 2001; Olivares et al., 2002; Groth et al., 2004; Ma et al., 2006). We named these pseudo attP sites according to their chromosomal location, for example, CpsF4 for C. hircus pseudo attP sites obtained from fibroblast cells and located in chromosome 4. The result showed that 4 of the 11 events shared the same crossover point and two pseudo attP sites (CpsF5b and CpsF28) were found in one colony. Thus, eight pseudo attP sites utilized by φC31 integrase were identified finally (Table 1).

Table 2.

The Composite of Crossover Point for Each Pseudo attP Site

| site | attB arm | Chromosomal DNA arm |

|---|---|---|

| CpsF4 | tctcgaagccgcggtgcgggtgcca: : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : :GGCTGTTTCTTAAAGGAAGGACTTT | |

| CpsF5a | tctcgaagccgcggtgcgggtgccagggcgtgcccTTG: : :GCCCATGCCAGTATTCTTGGGCTTCCCTTGTG | |

| CpsF5b | tctcgaagccgcggtgcgggtgccagg: : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : :ATCATGAAGCTTTCAATGGCATAA | |

| CpsF10 | tctcgaagccgcggtgcgggtgccagggcgtgccc: : : :GGGGTCTTCCTGGCACCCCTCAATGGTCTCTTGC | |

| CpsF16 | tctcgaagccgcggtgcgggtgccagggcgtgc: : : : : : : : : : :TTTTATAAGTGGTAACAAATCGCGCAACT | |

| CpsF19 | tctcgaagccgcggtgcgggtgccagggcgtg: : : : : : : : : : :CCTGGAGAGGGGTGGGTGGGAACTGGCAAA | |

| CpsF28 | tctcgaagccgcggtgcgggtgccagggcg: : : : : : : : : : : : : :GGCCCCTATCTTTGAGTCGCCTTGCTGCT | |

| CpsF X | tctcgaagccgcggtgcgggtgccagggc: : : : : : : : : :CGCCCCACCCTGGCCCTCTTTGTCTCGCTAGCAT | |

| Perfect attL | tctcgaagccgcggtgcgggtgccagggcgtgcccTTGAGTTCTCTCAGTTGGGGGCGTAGGGTCGCCGACAT | |

Colons represent bases missing in the point.

The TTG core in perfect attL is shown with underline.

Table 1.

Pseudo attP Sites in the Capra hircus Genome

| Site | Sequence | Identity to attP (%) | Genomic location | Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| attP | CCCCAACTGGGGTAACCTTTGAGTTCTCTCAGTTGGGGG | 100 | – | – |

| CpsF4 | CTGCAAAGCCAGTGTACCTTCTGCTACCCAAGGCTGTTT | 38.46 | Chr.4 | Intergenic |

| CpsF5a | GATCCCCTGGAGAAGCAATAGACTGCCCATGCCAGTATT | 38.46 | Chr.5 | Intergenic |

| CpsF5b | AACATATTTAGATATTCTTAGGACTGTGGAATATCATGA | 38.46 | Chr.5 | Intron |

| CpsF10 | GATAAGTGGTTGGAGAACCTTTGGGGTCTTCCTGGCACC | 28.21 | Chr.10 | Intron |

| CpsF16 | AGACGGTAGCTACAGCCAGTGAATGCATTTTATAAGTGG | 38.46 | Chr.16 | Intergenic |

| CpsF19 | CACCACCACGCACTGGCCTTAAGTTTCCTGGAGAGGGGT | 48.72 | Chr.19 | Intron |

| CpsF28 | GCCCAGGGGAGCTAGAAGATTCTTCATGGCCCCTATCTT | 33.33 | Chr.28 | Intron |

| CpsFX | TTTCAGACCAGTGGAAGCCCTACGCCCCACCCTGGCCCT | 25.64 | Chr.X | Intergenic |

The TTG core in phage attP site is shown in bold.

Genomic integration efficiency of φC31 integrase in fibroblast cells

To examine the integration efficiency of φC31 integrase, we co-transfected fibroblast cells with different ratios of the pEGFP-N1-attB transgene vector and the integrase expression plasmid (pCMV-Int) (Fig. 2). Empty plasmid was used to equalize the total amount of DNA in every transfection. By counting the number of G418-resistant colonies, we found as expected that the more integrase expression plasmid added, the greater the number of transgenic colonies formed. The number of resistant colonies obtained with a transfection ratio of 1:20 was 3.1-fold greater than observed with no integrase expression vector (1:0), which demonstrated φC31 integrase significantly increases integration frequency.

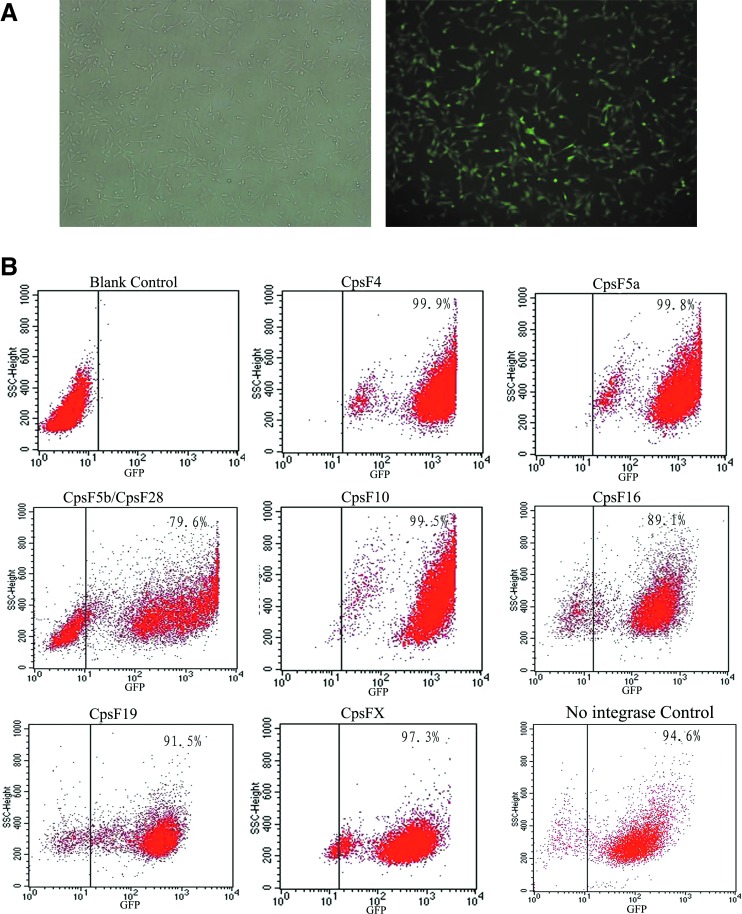

GFP expression in different integration sites

It has been reported that the integrations induced by φC31 integrase support high-level and long-term expression of foreign genes (Ortiz-Urda et al., 2002, 2003; Quenneville et al., 2004; Held et al., 2005; Keravala et al., 2006; Ou et al., 2009). We observed long-term expression up to 30 days for GFP integrated at the pseudo attP sites of C. hircus fibroblast cells, Figure 3A. To measure variation among expression levels of transgenes at different pseudo attP sites, we analyzed the GFP expression from integrations at eight pseudo attP sites by FACS, Figure 3B. The median GFP unit for integrase-mediated colonies (CpsF4, CpsF5a, CpsF5b/CpsF28, CpsF10, CpsF16, CpsF19, CpsFX) was 948±478, whereas for non-integrase mediated colonies was 217±91. The GFP expression in integrase-mediated colonies is higher than non-integrase media colonies (p<0.05). The GFP constructs integrated at CpsF4, CpsF5a, CpsF5b/CpsF28, and CpsF10 were expressed at a relatively high level (over 1000 median GFP fluorescence units). For the other colonies, the lowest expression level was more than 200 median GFP fluorescence units, higher than non-integrase control. The high expression level of foreign genes is significant for animal bioengineering such as the mammary gland bioreactor.

FIG. 3.

The expression of GFP integrated in the pseudo attP sites. (A) GFP expression was observed by fluorescence microscopy (right) compared to light images (left, magnification 40×) in fibroblasts 30 days after transfection. (B) FACS quantitation of GFP fluorescence from transgenes integrated at different genomic sites. Non-transfected C. hircus fibroblast cells were used as the control. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/dna

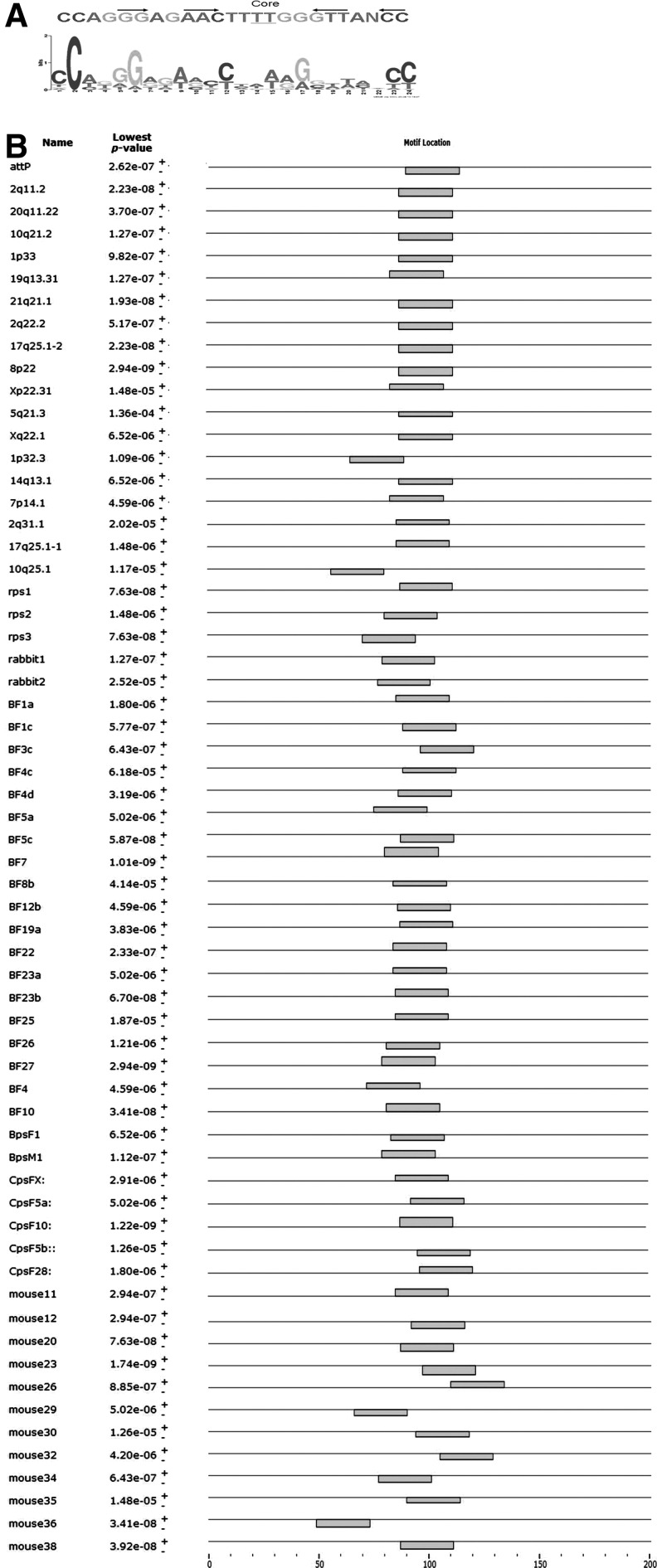

φC31 integrase sites are associated with a DNA consensus sequence

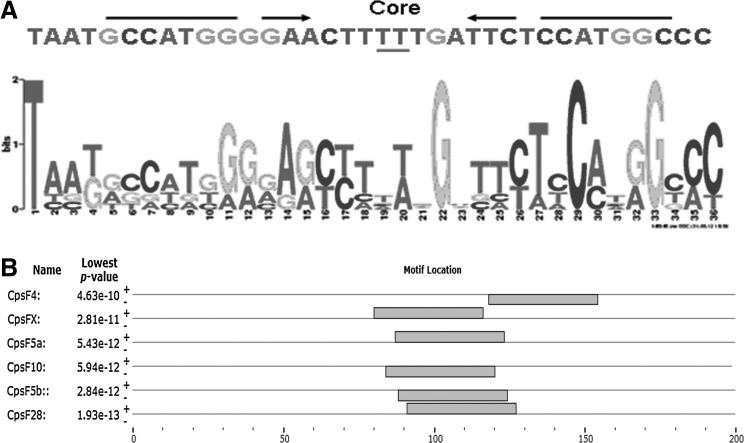

We hypothesized that the pseudo attP sites in C. hircus genome may occur near a separate sequence motif. Using MEME motif finder (Held et al., 2005) to analyze genomic sequences surrounding each pseudo attP site, a significant (E=7.6×10−3) consensus motif (Fig. 4A) was found near six of eight goat sites (Fig. 4B), similar to the level of 65/81 found in human genome (Chalberg et al., 2006) and 29/33 found in bovine genome (Qu et al., 2012). No significant motif was found in the random sequence dataset. The analysis using the other known pseudo sites with the random sequences showed that none of the random sequences were grouped with the motif. Except for CpsF4 (∼50 bp downsteam of the crossover), the motif was found near the pseudo attP sequence and the core TT sequences found in canonical attP are also present at the center of this motif. The motif is 36 bp long and contains inverted repeats flanking the core TT, a feature associated with integration by φC31 integrase.

FIG. 4.

DNA sequence features near pseudo attP sites in the C. hircus genome. The pseudo attP sites were compared to wild-type attP, and adjacent sequences were tested for a common motif using MEME motif finder. (A) A shared 36 bp motif was identified in goat sequences near the pseudo attP site. This motif contains the attP core flanked by inverted repeats (arrows). (B) The locations of motifs sorted by the lowest p-value among all sites in the adjacent sequences are indicated relative to their associated pseudo attP sites. The thin line shows the flanking sequence around the pseudo attP site, the center of the sequence is the break point. The box shows the location of the motif in the sequence.

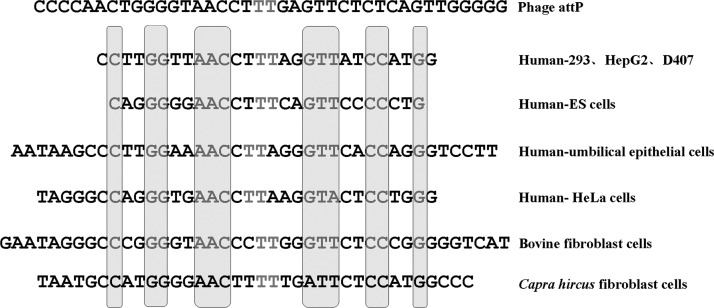

Pseudo attP sites in mammalian genomes have only partial sequence identity with wild-type attP (Groth et al., 2004; Calos, 2006). Compared with pseudo attP consensus variants found in individual human cell lines (Groth et al., 2004; Calos, 2006) and in bovine fibroblast cells (Qu et al., 2012), the consensus of C. hircus is highly homologous to these previously identified sites (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

The pseudo attP site consensus sequence motif identified in C. hircus fibroblast cells aligned with pseudo attP consensus sequences that have been previously identified (Groth et al., 2004; Calos, 2006; Qu et al., 2012). Red lettersin the center indicate the core sequence; highlighted boxes show the highly conserved base pairs.

Pseudo attP sites have been discovered in many species including humans, mice, rats, rabbits, sheep, Drosophila, and cattle (Groth et al., 2004; Chalberg et al., 2005, 2006; Keravala et al., 2006; Ma et al., 2006; Ehrhardt et al., 2007; Ni et al., 2012; Qu et al., 2012). We retrieved database sequences that are adjacent to 97 pseudo attP sites in these various species, targeting 200 bp sequence flanking the pseudo attP. The motif discovery of pseudo site dataset was significantly better than that of random sequences (E=1.5×10−57). MEME motif finder identified a similar 24 bp motif shared by 61 out of 97 sequences, all from mammalian genomes and not in Drosophila (Fig. 6). The 24 bp motif also shares the strict format summarized in human, bovine, and C. hircus (Fig. 5).

FIG. 6.

Sequence characteristics adjacent to pseudo attP sites in different species. (A) The nucleotide distribution is shown for the multi-species consensus of the motif predicted by MEME. (B) The position of the predicted motif is indicated for DNA sequences surrounding 61 pseudo attP sites discovered in many species including human, mouse, rat, rabbit, cattle, and goat.

Discussion

Transgenic technology is a powerful tool in life sciences and is commonly used to produce transgenic animals for generating disease models, proteins with high value for pharmaceutical use, and identifying the gene functions. However, the lack of technologies for culturing of ES cells of C. hircus in vitro has made the SCNT a powerful alternative tool for transgenic C. hircus production (Ohkoshi et al., 2003). The number of species identified to support insertion by the φC31 integrase system has been growing consistently over the past decade. Importantly, the identified site-specific integration of the pseudo attP sites mediated by this system will provide an efficient approach to produce transgenic cells or cloned C. hircus with high level and long-term foreign gene expression. The present study showed that φC31 integrase could induce efficient site-specific integration in C. hircus fibroblast cells by recognizing the pseudo attP sites in C. hircus genome. Thus, the φC31 integrase system could be used as a valuable tool for genetic engineering of the C. hircus genome and the optimization of this system (Raymand and Soriano, 2007; Keravala et al., 2009; Tasic et al., 2011; Xie et al., 2012) would facilitate the research on transgenic goats and in utero xenograft goat models (Zeng et al., 2005).

Eight pseudo attP sites were identified and two pseudo attP sites (CpsF5b and CpsF28) were found in one colony. According to the low purity of the colony (79.6%) measured by FACS and the copy number (0.89) of GFP in the colony measured by qRT-PCR (data not shown), we deduced that the two pseudo attP sites—CpsF5b and CpsF28—were identified from mixed colonies from two progenitor cells containing the two pseudo attP sites respectively.

The expression levels of integrated GFP at these sites were examined. The FACS results showed that the GFP expression in integrase-mediated colonies was higher than non-integrase-mediated colonies (948±478 vs. 217±91, p<0.05); half of them yielded a high expression level (over 1000 median GFP fluorescence units). On the other hand, the lowest amount of expression was more than 200 median GFP fluorescence, higher than the non-integrase control.

It has been reported that the integration induced by φC31 integrase can produce high-level and long-term expression of the foreign genes (Ortiz-Urda et al., 2002, 2003; Quenneville et al., 2004; Held et al., 2005; Keravala et al., 2006). Expression level may be related to the location of the events and the chromosomal context. By aligning the sequences of these sites with the C. hircus genome using BLAST, we found that these sites were intergenic or intronic. No integration in coding exons was identified. Our findings are consistent with those from other mammalian systems (Groth et al., 2004; Chalberg et al., 2005, 2006; Keravala et al., 2006; Ma et al., 2006; Ehrhardt et al., 2007; Qu et al., 2012).

Bioinformatics analysis indicated that pseudo attP sites in C. hircus shared a 36-bp motif similar to pseudo attP sites in genomes of other mammals including humans, mice, and cattle. Furthermore, analysis of the sequences flanking the sites we identified showed that pseudo attP sites of all mammals tested but not Drosophila share a DNA consensus sequence; this may be related to the genomic context and evolution of species. Alignment of pseudo attP site MEME motifs defined in different cell lines (Groth et al., 2000; Chalberg et al., 2006; Thyagarajan et al., 2008; Nishiumi et al., 2009; Sivalingam et al., 2010), bovine fibroblasts (Qu et al., 2012) and C. hircus fibroblasts confirmed that a conserved sequence with partial palindromic character known to be recognized by φC31 integrase plays an important role in recombination.

Conclusion

Our study showed that φC31 integrase can induce efficient site-specific integration in C. hircus fibroblast cells by recognizing the pseudo attP sites in its genome. Eight pseudo attP sites were identified in C. hircus genome and all these sites were intergenic or intronic and no integrations in coding exons. The expression levels of integrated GFP at these sites were examined. An integrate hotspot named CpsF4 on chromosome 4 was identified due to its higher frequency of integration and higher level of expression. Bioinformatics analysis indicated that pseudo attP sites in C. hircus shared a 36-bp motif and the pseudo attP sites of all mammals tested share a DNA consensus sequence.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (Nos. 2014ZX08008-004, 2013ZX08008-004, 2011ZX08008-004 and 2009ZX08010-018B). We thank Dr. M.P. Calos (Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA) for pCMV-Int plasmid.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Andreas S., Schwenk F., Kuter-Luks B., Faust N., and Kuhn R. (2002). Enhanced efficiency through nuclear localization signal fusion on phage PhiC31-integrase: activity comparison with Cre and FLPe recombinase in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res 30,2299–2306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belteki G., Gertsenstein M., Ow D.W., and Nagy A. (2003). Site-specific cassette exchange and germline transmission with mouse ES cells expressing phiC31 integrase. Nat Biotechnol 21,321–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calos M.P. (2006). The phiC31 integrase system for gene therapy. Curr Gene Ther 6,633–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalberg T.W., Genise H.L., Vollrath D., and Calos M.P. (2005). phiC31 integrase confers genomic integration and long-term transgene expression in rat retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 46,2140–2146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalberg T.W., Portlock J.L., Olivares E.C., Thyagarajan B., Kirby P.J., Hillman R.T., Hoelters J., and Calos M.P. (2006). Integration specificity of phage phiC31 integrase in the human genome. J Mol Biol 357,28–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt A., Yant S.R., Giering J.C., Xu H., Engler J.A., and Kay M.A. (2007). Somatic integration from an adenoviral hybrid vector into a hot spot in mouse liver results in persistent transgene expression levels in vivo. Mol Ther 15,146–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth A.C., Fish M., Nusse R., and Calos M.P. (2004). Construction of transgenic Drosophila by using the site-specific integrase from phage phiC31. Genetics 166,1775–1782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth A.C., Olivares E.C., Thyagarajan B., and Calos M.P. (2000). A phage integrase directs efficient site-specific integration in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97,5995–6000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Held P.K., Olivares E.C., Aguilar C.P., Finegold M., Calos M.P., and Grompe M. (2005). In vivo correction of murine hereditary tyrosinemia type I by phiC31 integrase-mediated gene delivery. Mol Ther 11,399–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keravala A., Portlock J.L., Nash J.A., Vitrant D.G., Robbins P.D., and Calos M.P. (2006). PhiC31 integrase mediates integration in cultured synovial cells and enhances gene expression in rabbit joints. J Gene Med 8,1008–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keravala A., Lee S., Thyagarajan B., Olivares E.C., Gabrovsky V.E., Woodard L.E., and Calos M.P. (2009). Mutational derivatives of PhiC31 integrase with increased efficiency and specificity. Mol Ther 17,112–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Maddison L.A., and Chen W. (2010). PhiC31 integrase induces efficient site-specific excision in zebrafish. Transgenic Res 20,183–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q.W., Sheng H.Q., Yan J.B., Cheng S., Huang Y., Chen-Tsai Y., Ren Z.R., Huang S.Z. and Zeng Y.T. (2006). Identification of pseudo attP sites for phage phiC31 integrase in bovine genome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 345,984–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni W., Hu S., Qiao J., Wang Y., Shi H., Wang Y., He Z., Li G., and Chen C. (2012). PhiC31 integrase mediates efficient site-specific integration in sheep fibroblasts. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 76,2093–2095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiumi F., Sone T., Kishine H., Thyagarajan B., Kogure T., Miyawaki A., Chesnut J.D., and Imamoto F. (2009). Simultaneous single cell stable expression of 2–4 cDNAs in HeLaS3 using phiC31 integrase system. Cell Struct Funct 34,47–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkoshi K., Takahashi S., Koyama S., Akaqi S., Adachi N., Furusawa T., Fujimoto J., Takeda K., Kubo M., Lzaike Y., and Tokunaga T. (2003). Invitro oocyte culture and somatic cell nuclear transfer used to produce a live-born cloned goat. Cloning Stem Cells 5,109–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares E.C., Hollis R.P., Chalberg T.W., Meuse L., Kay M.A., and Calos M.P. (2002). Site-specific genomic integration produces therapeutic Factor IX levels in mice. Nat Biotechnol 20,1124–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Urda S., Thyagarajan B., Keene D.R., Lin Q., Calos M.P., and Khavari P.A. (2003). PhiC31 integrase-mediated nonviral genetic correction of junctional epidermolysis bullosa. Hum Gene Ther 14,923–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Urda S., Thyagarajan B., Keene D.R., Lin Q., Fang M., Calos M.P., and Khavari P.A. (2002). Stable nonviral genetic correction of inherited human skin disease. Nat Med 8,1166–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou H.L., Huang Y., Qu L.J., Xu M., Yan J.B., Ren Z.R., Huang S.Z., and Zeng Y.T. (2009). A phiC31 integrase-mediated integration hotspot in favor of transgene expression exists in the bovine genome. FEBS J 276,155–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu L., Ma Q., Zhou Z., Ma H., Huang Y., Huang S., Zeng F., and Zeng Y. (2012). A profile of native integration sites used by phiC31 integrase in the bovine genome. J Genet Genomics 39,217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quenneville S.P., Chapdelaine P., Rousseau J., Beaulieu J., Caron N.J., Skuk D., Mills P., Olivares E.C., Calos M.P., and Tremblay J.P. (2004). Nucleofection of muscle-derived stem cells and myoblasts with phiC31 integrase: stable expression of a full-length-dystrophin fusion gene by human myoblasts. Mol Ther 10,679–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymand C.S., and Soriano P. (2007). High-efficiency FLP and PhiC31 site-specific recombination in mammalian cells. PLoS One 2,el62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivalingam J., Krishnan S., Ng W.H., Lee S.S., Phan T.T., and Kon O.L. (2010). Biosafety assessment of site-directed transgene integration in human umbilical cord-lining cells. Mol Ther 18,1346–1356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasic B., Hippenmeyer S., Wang C., Gamboa M., Zong H., Chen-Tsai Y., and Luo L. (2011). Site-specific integrase-mediated transgenesis in mice via pronuclear injection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108,7902–7907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe H.M., and Smith M.C. (1998). In vitro site-specific integration of bacteriophage DNA catalyzed by a recombinase of the resolvase/invertase family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95,5505–5510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyagarajan B., Liu Y., Shin S., Lakshmipathy U., Scheyhing K., Xue H., Ellerstrom C., Strehl R., Hyllner J., Rao M.S., and Chesnut J.D. (2008). Creation of engineered human embryonic stem cell lines using phiC31 integrase. Stem Cells 26,119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyagarajan B., Olivares E.C., Hollis R.P., Ginsburg D.S., and Calos M.P. (2001). Site-specific genomic integration in mammalian cells mediated by phage phiC31 integrase. Mol Cell Biol 21,3926–3934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmut I., Beaujean N., de Sousa P.A., Dinnyes A., King T.J., Paterson L.A., Wells D.N., and Yong L.E. (2002). Somatic cell nuclear transfer. Nature 419,583–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie F., Ma Q.W., Jiang S.Z., Ren Z.R., Wang J., Huang S.Z., Zeng F.Y., and Zeng Y.T. (2012). Adjusting the attB site in donor plasmid improves the efficiency of PhiC31 integrase system. DNA Cell Biol 31,1335–1340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng F., Chen M.J., Katsumata M., Huang W.Y., Gong Z.J., Hu W., Qian H., Xiao Y.P., Ren Z.R., and Huang S.Z. (2005). Indentification and characterization of enfrafted human cells in human/goat xenogenetic transplantation chimerism. DNA Cell Biol 24,403–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]