Abstract

Developing language treatments that not only improve trained items but also promote generalization to untrained items is a major focus in aphasia research. This study is a replication and extension of previous work that found that training abstract words in a particular context-category promotes generalization to concrete words but not vice versa (Kiran, Sandberg, & Abbott, 2009). Twelve persons with aphasia (5 female) with varying types and degrees of severity participated in a generative naming treatment based on the complexity account of treatment efficacy (CATE; Thompson, Shapiro, Kiran, & Sobecks, 2003). All participants were trained to generate abstract words in a particular context-category by analyzing the semantic features of the target words. Two other context-categories were used as controls. Ten of the twelve participants improved on the trained abstract words in the trained context-category. Eight of the ten participants who responded to treatment also generalized to concrete words in the same context-category. These results suggest that this treatment is both efficacious and efficient. We discuss possible mechanisms of training and generalization effects.

Introduction

Many successful treatments for different aspects of language deficits exist and are routinely used for persons with aphasia (PWA) (see Kiran & Sandberg, 2012 for a review). Generally, language therapy is considered to be successful if the items that are directly trained improve as a function of treatment. However, a major goal in clinical aphasiology is to develop treatments that have a greater impact on communication than simply improving trained items. One way to increase the utility of treatment is through generalization to untrained items. Thus, most clinical research in aphasia, even if not explicitly focused on it, tests generalization effects of the studied treatment.

One method for promoting generalization from trained to untrained items in language therapy is the Complexity Account of Treatment Efficacy (CATE). The CATE was developed by Thompson, Shapiro, Kiran, and Sobecks (2003) to systematically facilitate generalization in language therapy. In this method, more complex structures are trained to facilitate generalization to less complex structures of the same type. For example, training more complex sentences with Wh- movement promotes generalization to less complex sentences with Wh- movement, but not vice versa and not to sentences with NP movement. The authors attribute this generalization to the fact that all of the information attached to the simple forms is contained within the complex forms. According to Nadeau and Kendall (2006), this example of generalization is attributable to the “generalization of knowledge acquired in therapy (e.g., semantic features, phonological sequences, and syntactic techniques) to other knowledge that shares these features or sequences, or to situations that allow application of acquired techniques,” (Nadeau & Kendall, 2006, p. 10) as opposed to the acquisition of a skill, strategy, or motivation.

The CATE has been applied to typicality, bilingualism, and concreteness/imageability (Edmonds & Kiran, 2006; Kiran, 2007, 2008; Kiran & Abbott, 2007; Kiran & Roberts, 2010; Kiran et al., 2009; Kiran, Sandberg, & Sebastian, 2011; Kiran & Thompson, 2003; Thompson, 2007). In the case of concreteness/imageability, complexity is based upon psycholinguistic theories of the concreteness effect, which is the tendency to perform better during linguistic tasks involving concrete words (e.g., sofa) than during those involving abstract words (e.g., guilt). Abstract and concrete words exist along continuums of imageability – the ease with which a mental image of the concept can be produced – and concreteness – the degree to which a concept is perceived by the senses. Abstract words have lower imageability and concreteness values and concrete words have higher imageability and concreteness values.

The concreteness effect has been well-studied in both normal and disordered language processing. For example, normal subjects exhibit longer lexical decision times for abstract words than for concrete words (Bleasdale, 1987; de Groot, 1989; James, 1975), longer word association times and fewer associations for abstract than concrete words (de Groot, 1989), better recall of concrete word pairs and sentences than abstract word pairs and sentences (see Paivio, 1991 for a review), and increased ease of predication (generating semantic features) for concrete over abstract words (Jones, 1985). Additionally, bilingual subjects have shown an advantage for concrete words during priming and naming to definition tasks (Kiran & Tuchtenhagen, 2005) and foreign-language learners show this advantage during foreign language vocabulary recall (de Groot & Keijzer, 2000). Furthermore, several studies have documented the effect that concreteness and imageability have on language processing in aphasia (e.g., Barry & Gerhand, 2003; Crutch & Warrington, 2005; Martin & Saffran, 1997, 1999; Martin, Saffran, & Dell, 1996; Newton & Barry, 1997; Nickels & Howard, 1995). For example, Nickels and Howard (1995) found that even in confrontation naming, which biases the stimuli to be more imageable and concrete in nature, naming performance in a variety of persons with aphasia correlated with imageability and concreteness. Furthermore, Martin and Saffran showed that both repetition (1997) and word list learning (1999) in aphasia are affected by imageability and that this effect is mediated by semantic ability, such that patients with higher semantic performance are more affected by imageability than those with lower semantic performance.

Although not specifically designed to, theories developed to explain this concreteness effect also help explain differences in complexity between abstract and concrete words. The dual-coding theory (DCT) posits that abstract words are encoded into the semantic system with only verbal information, whereas concrete words are encoded into the semantic system with both verbal and multi-modal sensory information (see Paivio, 1991 for a review). Thus we can speculate that the verbal-only basis of abstract words is what makes them more complex than concrete words, which have additional support from sensory processing. The context-availability theory (CAT) suggests that the concreteness effect is not due to concreteness or imageability per se, but to the fact that concrete concepts are context-independent – they carry all of the necessary context with them and do not need additional context to disambiguate meaning – and that abstract concepts are context-dependent – they require additional context to disambiguate meaning (Schwanenflugel, Harnishfeger, & Stowe, 1988). Thus we can posit that the fact that abstract words require context to be understood readily (e.g., the meaning of guilt changes based on whether it’s relating to a courthouse or a church, whether it’s describing a state of being or a feeling) makes them more complex than concrete words. Additionally, abstract words have a paucity of semantic features and are difficult to predicate, whereas concrete words have an abundance of semantic features and are therefore easily predicated (Jones, 1985; Plaut & Shallice, 1991). This difference in the semantic feature profile of abstract and concrete words can also be considered to make abstract words more complex than concrete words.

Specific to aphasia, Newton and Barry (1997) proposed that the exaggerated concreteness effect seen in deep dyslexia reflects problems with lexicalization, or the generation of the appropriate word from the semantic representation. The authors propose that concrete words have strong and specific representations with little spreading activation, but abstract words have less specific representations with more spreading activation to a variety of concepts. Thus, the “threshold” for choosing the correct word is higher in deep dyslexia and therefore the concreteness effect is exaggerated, with concrete words being more likely to cross this raised threshold. The authors coined this theory the NICE model (normal isolated centrally expressed semantics). The notion that abstract words are more diversely connected with other concepts than concrete words provides additional support that abstract words are more complex than concrete words. Furthermore, de Groot (1989) showed that in healthy adults, abstract words elicited associations with both abstract and concrete words, while concrete words mainly elicited associations with other concrete words.

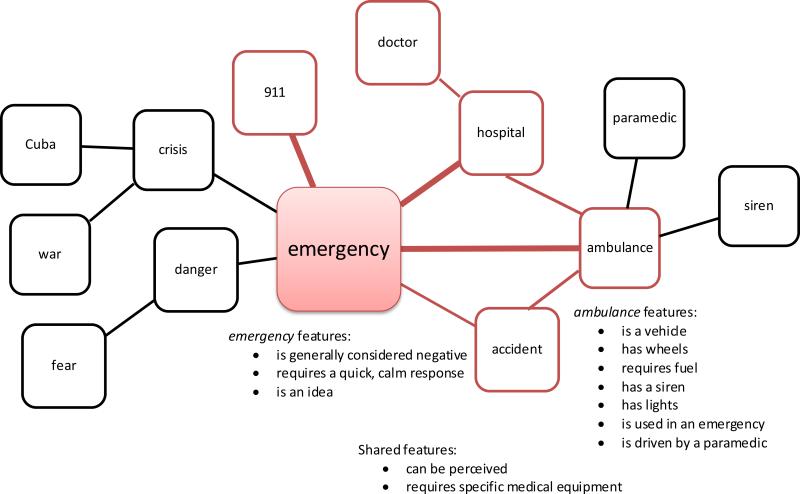

Together, these theories suggest that not only are abstract words more complex than concrete words, but that there is a plausible mechanism for generalization from abstract to concrete words. Suppose we combine these theories into one framework (see Figure 1), such that abstract words have connections with roughly an equal number of abstract and concrete concepts while concrete words have more connections with concrete than abstract concepts (de Groot, 1989). For example, emergency is associated with crisis, danger, 911, hospital, ambulance, and accident while the concrete word ambulance is associated with emergency, accident, hospital, siren, and paramedic (Kiss, Armstrong, Milroy, & Piper, 1973; Nelson, McEvoy, & Schreiber, 1998). It is plausible that these associations reflect the semantic features for concrete words but not necessarily for abstract words, which may contribute to the relative difficulty in predication of abstract words and thus the relative paucity of semantic features (Jones, 1985; Plaut & Shallice, 1991). For example, semantic features for an ambulance may include: has a siren and is used in an emergency; whereas that semantic features for emergency may include: is generally considered negative and requires a quick, calm response (Kiran & Abbott, 2007; Kiran et al., 2009). This may be the result of the verbally-based encoding for abstract words versus the perceptually-based encoding for concrete words (Paivio, 1991).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the semantic network for the abstract word emergency and an associated concrete word, ambulance. This figure illustrates a hypothetical schematic based on existing theories of the concreteness effect. The associations for both emergency and ambulance are shown, based on existing norms (Kiss, Armstrong, Milroy, & Piper, 1973; Nelson, McEvoy, & Schreiber, 1998). The semantic features, based on previous treatment studies (Kiran & Abbott, 2007; Kiran et al., 2009) are also shown. Abstract words have more diverse associations while concrete words have more specific associations, related to semantic features. When abstract words are trained, activation spreads to related concepts. When the context is constrained, spreading activation is strongest within the trained context-category, e.g., hospital, shown in red. See text for details.

Within this framework, it is plausible that the mechanism of generalization from abstract to concrete words is spreading activation (Collins & Loftus, 1975). Normally, when semantic features of concrete words, such as ambulance, are trained, the representation for ambulance strengthens as do the semantic features for ambulance. This means that whatever shares semantic features for ambulance will also be strengthened and will most likely improve, as is the premise for studies showing generalization effects of semantic feature treatment (Kiran & Bassetto, 2008). However, the spreading activation is limited to the word trained and a relatively constrained associative network (Newton & Barry, 1997) that includes mainly the semantic features that are trained. On the other hand, when the semantic features of abstract words, such as emergency, are trained and the representation of emergency strengthens, the spreading activation is more extensive, since abstract words have more diverse connections (Newton & Barry, 1997). When the category is constrained to a particular context, such as hospital, the abstract words become more salient (Schwanenflugel et al., 1988) and thus, connections with other abstract words and concrete words within the context of a hospital (see red boxes in Figure 1) are more strengthened than those that are out-of-context (see black boxes in Figure 1).

Kiran et al. (2009) applied this notion of complexity and spreading activation in treatment to a generative naming therapy that was constrained by context. The hypothesis was that training abstract words – the more complex items – would result in retrieval of the trained abstract words as well as generalization to concrete words – the less complex items – within the same context category. However, training concrete words would result in retrieval of the trained concrete words, but no generalization would be observed. Indeed, using a multiple baseline design with four persons with aphasia, the researchers found that three of the four participants showed both training and generalization effects when abstract words were trained, but when concrete words were trained, only training effects were apparent. The fourth participant showed neither training nor generalization effects. The results of this study indicate that training abstract words is superior to training concrete words in a generative word- finding therapy. However, this group of participants was fairly small and homogenous. While these results are promising, this treatment has not yet been extended to more persons with aphasia.

Therefore, the current study is an extension of Kiran et al. (2009). We believe that training abstract words does, in fact, promote generalization to concrete words and that this generalization effect is grounded in psycholinguistic theory. We aim to explore the efficacy of training abstract words on both direct training and generalization effects in a larger sample with varying degrees of aphasia severity and type. Our goal was not to compare the efficacy of training abstract versus concrete words, but rather to examine additional questions about the underlying mechanisms of training and generalization when abstract words are trained.

There are surprisingly few studies specifically exploring the utilization of abstract words in treatment, given the importance of abstract words in everyday conversation. We are aware of only one other study that specifically targeted abstract words in treatment. Kim and Beaudoin-Parsons (2007) showed the efficacy of using bigraph-syllable pairing for the treatment of low-imageability word reading in deep dyslexia. The fact that the treatment in this study was for reading rather than word finding only underscores the need for more work in this area. Indeed, in a recent review, Renvall, Nickels, and Davidson (2013) pointed out the paucity of treatment studies examining the effects of using words other than concrete nouns and verbs though most meaningful conversation requires abstract concepts. We intend to help fill this gap in the literature.

Our questions were: 1) How efficacious is training abstract words? 2) What is the effect of generalization to concrete words when abstract words are trained? 3) Are there individual differences in generalization? 4) How does the quality of generative naming responses change after treatment?

We hypothesized that as in Kiran et al. (2009), training abstract words will result in improvement on the trained items and training abstract words will promote generalization to concrete words in the same context-category. We further hypothesize that this training/generalization effect will be seen across patients to varying degrees and that generative responses to each context-category in general will become more focused and appropriate as a result of treatment – as subjectively noted in Kiran et al. (2009).

Methods

Participants

Twelve right-handed native English-speaking individuals with aphasia (7 male, 5 female) ranging in age from 47 to 75 (M = 60, SD = 9) participated in this study. All participants experienced a cerebrovascular accident in the distribution of the left middle cerebral artery and were in the chronic stage of recovery as evidenced by time post-onset of at least six months. All participants exhibited normal or corrected-to-normal hearing and visual acuity and had at least a high school education; most also had college degrees. Participants gave informed consent according to the Boston University Human Subjects Protocol.

Assessment

Eligibility for participation in the treatment was based on category-specific generative naming performance of at or below 50% accuracy for both abstract and concrete words. All participants met this requirement. Additionally, all participants were given a battery of standardized language tests, including the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB-R; Kertesz, 2006) to establish the type and severity of aphasia, the Boston Naming Test (BNT; Goodglass, Kaplan, & Weintraub, 1983) to determine confrontation naming ability, the Psycholinguistic Assessment of Language Processing in Aphasia (PALPA; Kay, Lesser, & Coltheart, 1992) to determine specific deficits of access to the semantic system, the Pyramids and Palm Trees (PAPT; Howard & Patterson, 1992) to determine overall soundness of the semantic system, and the Cognitive Linguistic Quick Test (CLQT; Helm-Estabrooks, 2001) to determine the relative contribution of cognitive deficits such as attention and memory to language dysfunction. Aphasia severity ranged from mild to severe, with the lowest WAB AQ score at 41.7. Confrontation naming ability ranged from 22% accuracy, which is below the aphasia average (51% accuracy) to above 78% accuracy, which is within normal limits. General semantic processing ranged from mildly impaired (75% accuracy) to no clinical impairment (above 90% accuracy), with only three participants exhibiting mild impairment. See Table 1 for full demographic information.

Table 1.

Demographic Information for All Participants

| Patient | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 | P10 | P11 | P12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 57 | 66 | 61 | 56 | 59 | 47 | 48 | 74 | 53 | 69 | 56 | 75 |

| Sex | F | F | F | M | M | M | M | F | M | M | F | M |

| Months Post Stroke | 38 | 15 | 54 | 76 | 23 | 42 | 93 | 134 | 117 | 16 | 7 | 11 |

| Lesion Region | LMCA | LMCA | LMCA | LMCA | LMCA | LMCA | LMCA | LMCA | LMCA | LMCA | LMCA | LMCA |

| Western Aphasia Battery | ||||||||||||

| Aphasia Quotient | 99.2 | 82.2 | 74.4 | 77.7 | 78.6 | 95.5 | 72.5 | 90.8 | 41.7 | 97.1 | 84.7 | 67.4 |

| Aphasia Type | Anomic | TCM | TCM | Conduction | Anomic | Anomic | Conduction | Anomic | Broca's | Anomic | Anomic | TCM |

| Apraxia Score | 100% | 100% | 95% | 97% | 85% | 97% | 92% | 92% | 85% | 100% | 98% | 97% |

| Boston Naming Test | 92% | 82% | 55% | 87% | 68% | 95% | 82% | 68% | 22% | 95% | 90% | 90% |

| Psycholinguistic Assessment of Language Processing in Aphasia | ||||||||||||

| Auditory Lexical Decision: HI | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 98% | 100% | 98% | 95% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Auditory Lexical Decision: LI | 100% | 88% | 100% | 98% | 98% | 98% | 93% | 95% | 93% | 100% | 95% | 98% |

| Visual Lexical Decision: HI | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 97% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Visual Lexical Decision: LI | 97% | 100% | 93% | 100% | 93% | 93% | 100% | 100% | 93% | 97% | 100% | 100% |

| Auditory Synonym Judgment: HI | 100% | 93% | 97% | 90% | 93% | 100% | 93% | 100% | 90% | 100% | 100% | 97% |

| Auditory Synonym Judgment: LI | 97% | 77% | 77% | 90% | 77% | 90% | 77% | 93% | 67% | 93% | 100% | 90% |

| Written Synonym Judgment: HI | 100% | 90% | 93% | 97% | 87% | 97% | 100% | 87% | 87% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Written Synonym Judgment: LI | 100% | 77% | 80% | 83% | 77% | 100% | 87% | 93% | 63% | 93% | 100% | 100% |

| Pyramids and Palm Trees | ||||||||||||

| Pictures | 96% | 75% | 88% | 98% | 94% | 100% | 90% | 77% | 88% | 98% | 98% | 96% |

| Written Words | 98% | 67% | 83% | 96% | 94% | 98% | 96% | 94% | 85% | 100% | 96% | 69% |

| Cognitive Linguistic Quick Test | ||||||||||||

| Composite Severity | WNL | severe | mild | WNL | WNL | WNL | mild | mild | mild | mild | WNL | mild |

| Baseline Categorical Word Generation | ||||||||||||

| Concrete | 30% | 3% | 10% | 33% | 17% | 37% | 17% | 20% | 10% | 20% | 37% | 17% |

| Abstract | 10% | 0% | 0% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 0% | 3% | 3% | 0% |

Note. LMCA = left middle cerebra artery, TCM = transcortical motor, HI = high imageability, LI = low imageability, WNL = within normal limits.

Treatment

Experimental design

Treatment was carried out in a multiple-baseline single-subject research design. Each participant was trained on abstract words in one of two context-categories (hospital, courthouse) while the untrained context-category and the context-category church served as controls. The context-category assignment was counterbalanced across participants (see Table 2 for details).

Table 2.

Counterbalancing of Context-Categories Across Participants

| Patient | Trained Category | Untrained Category | Control Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | hospital | courthouse | church |

| P2 | courthouse | hospital | church |

| P3 | courthouse | hospital | church |

| P4 | hospital | courthouse | church |

| P5 | courthouse | hospital | church |

| P6 | courthouse | hospital | church |

| P7 | hospital | courthouse | church |

| P8 | courthouse | hospital | church |

| P9 | hospital | courthouse | church |

| P10 | courthouse | hospital | church |

| P11 | hospital | courthouse | church |

| P12 | hospital | courthouse | church |

Stimuli

Since we used a generative naming paradigm rather than a confrontation naming paradigm, in order to track generative naming progress in a systematic way, we established a closed set of preferred abstract and concrete words for each trained context-category from association norms for the words hospital and courthouse (Kiss et al., 1973; Nelson et al., 1998) and from our previous treatment study using the same paradigm (Kiran et al., 2009), in which we obtained context-category exemplars for use in treatment from a group of healthy adults. Ten abstract words (e.g., justice) from each trained category (hospital, courthouse) were considered targets. Ten concrete words (e.g., lawyer) from each trained category were considered targets for generalization. Ten abstract and concrete words in the control category (church) were used to measure gains unrelated to category-specific training effects. Appendix A provides a list of all stimuli used in treatment. Note that for each participant, only abstract words in one context-category were trained during treatment. Care was taken to ensure that the abstract and concrete target words significantly differed on concreteness (p < .001) and imageability (p < .001) ratings (Gilhooly & Logie, 1980). Forty-five semantic features for each context-category were used to train the abstract target words in that context-category. Similar to Kiran et al. (2009), 15 of the 45 semantic features were generic features based on dictionary definitions of abstract and concrete (e.g., can be touched), 15 features were distracters that belong to another context-category (e.g., has feathers), and 15 features were patient-generated. Care was taken to ensure that none of the features contained target concrete words (see Appendix A for details).

Treatment protocol

Each participant received therapy twice per week for two hours each session. In each treatment session, patients practiced the following steps: 1) sort 40 target words – 20 from the trained context-category (hospital or courthouse) and 20 from the control context-category (church) – into their respective context-categories, 2) select six semantic features that apply to the abstract target word being trained from a field of 30 context-category features and 15 distracter features, 3) answer 15 yes/no questions of which five belong to the target, five belong to the context-category but not the target, and five are distracters that do not belong to the target or the context-category, 4) generate the target word being trained and a synonym, and 5) freely generate words in the trained context-category with specific feedback from the clinician. Steps 1 and 5 occurred only once per session, while steps 2-4 were performed for each of the target abstract words. During the first treatment session, with the help of the clinician, each participant generated features for each target word for use in steps 2 and 3 during the remaining treatment sessions. In this way, for each participant, many of the features were recognizable as associations that s/he had personally made with each of the target words. Again, care was taken to ensure that none of these “personalized” features contained target concrete words. See Appendix B for a detailed treatment protocol. The criteria for stopping treatment were: 80% accuracy on the trained items for two probes in a row or a total of 20 sessions, whichever came first. Generalization was examined on the untrained concrete examples within the context-category.

Testing protocol

Generative naming probes were conducted before, during, and after treatment. Participants were instructed to imagine themselves in the context-category being probed and say as many words in two minutes as they could think of that belonged in that context-category, being sure to mention ideas (abstract words) in addition to people and objects (concrete words). See Appendix C for details regarding testing and scoring protocols. Briefly, words generated that were on the preferred list (see Appendix A) were counted as correct targets. Other words that were not on the preferred list, but were plausibly within the context-category were counted as other acceptable responses. Three to five baseline probes were given during pre-treatment testing, treatment probes were given at the beginning of every second treatment session, and three post-treatment probes were given during post-treatment testing. An exception to this is that one participant only received two post-treatment probes due to time constraints and one participant received four post-treatment probes for stability. The first five participants were pilot participants for a larger project and were probed on all three context-categories throughout treatment. After pilot data were collected, we determined that it was more efficient and a better control to only include all three context-categories (hospital, courthouse, church) during pre- and post-treatment testing, while probing the trained context-category (hospital or courthouse) and the control context-category (church) throughout treatment. Thus, we utilized that protocol for the remaining seven participants. Importantly, this slight difference in testing protocol did not affect treatment outcomes or the conclusions that can be made regarding the efficacy and efficiency of the treatment.

Reliability

. At least 50% of the treatment sessions for each participant were video and audio recorded; most of these recordings contain a treatment probe. Reliability for both the independent variable (treatment) and dependent variable (generative naming responses) was conducted by members of the Aphasia Research Laboratory who were trained on the treatment and testing protocols. Point-to-point reliability on 50% of the dependent and independent variables was calculated resulting in 96% agreement on the dependent variable and 99% agreement on the independent variable, indicating high inter-rater reliability and high treatment fidelity.

Data analysis

To measure the overall efficacy of treatment across patients, the average percent correct pre-treatment was compared to the average percent correct post-treatment using a paired t-test for each context-category and for each word type. Note that because the task was generative naming, percent correct means the number of target words generated out of possible target words (N = 10). Other acceptable responses generated were recorded and entered into a different analysis. To measure the efficacy of treatment at the individual level, effect sizes (ES) for both trained items and generalized items were calculated for each participant. The mean of the baseline probe scores was subtracted from the mean of the post-treatment probe scores, and then divided by the standard deviation of the baseline probe scores. One participant (P2) discontinued treatment after eight weeks for personal reasons; therefore, ES was calculated using the scores from the last 2 probes. Additionally, cross-correlations were computed between abstract and concrete performance for both the trained category and the control category using all probe data points. This analysis acts as a complement to the ES calculation since it measures the trend in performance throughout therapy as opposed to only capturing pre- versus post-treatment performance. Finally, to look at trends of responses in the trained context-category from pre- to post-treatment across participants we performed a hierarchical cluster analysis in SPSS using Ward’s method. In this way, we can examine other acceptable responses and errors in addition to target responses, giving us an idea of how participants’ general word generation performance is changing as a response to treatment.

Results

How efficacious is training abstract words?

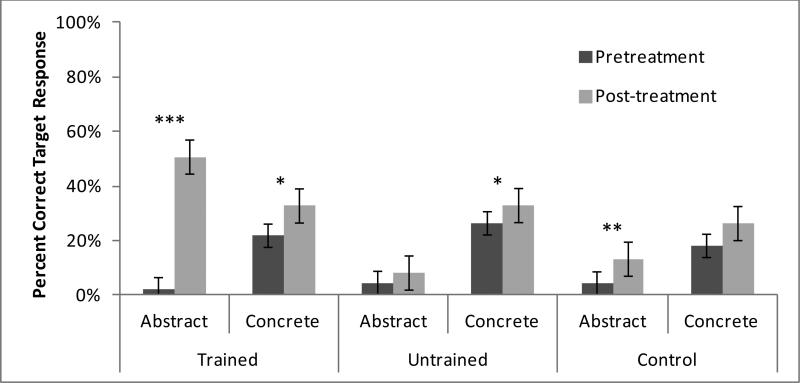

Paired t-tests comparing average pre-treatment versus post-treatment accuracy across patients showed statistically significant improvements for the trained abstract words (t = 5.49, p < .001). See Figure 2 for details. Therefore, training abstract words is efficacious for this group of PWA in general. Upon inspection of individual ESs, two participants showed no effect of treatment for the trained abstract words and will be discussed under the section entitled “non-responders.”

Figure 2.

Pre- versus post-treatment accuracy. This figure illustrates the change in accuracy from pre- to post-treatment, averaged across patients for each target word type within each type of context-category. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05

What is the effect of generalization to concrete words when abstract words are trained?

Paired t-tests comparing average pre-treatment versus post-treatment accuracy across patients showed statistically significant improvements for the untrained concrete words in the trained context-category (t = 2.39, p < .05). See Figure 2 for details. Therefore, in general, training abstract words promotes generalization to untrained concrete words in the same context-category for this group of PWA. Upon inspection of individual ESs, three of the ten participants who showed improvement for the trained abstract words did not show generalization to untrained concrete words in the same context-category and will be discussed under the section entitled “non-generalizers.”

Interestingly, some improvements were also noted in the untrained and control context-categories. Statistically significant increases occurred for untrained target abstract words (t = 4.34, p < .01), but not untrained target concrete words (t = 1.80, p = .10) in the control context-category (church), while in the untrained context-category (either hospital or courthouse), untrained target concrete words improved (t = 2.37, p < .05), but not untrained target abstract words (t = 1.10, p = .30). However, upon inspection of individual ESs, all but three “generalizers” do not show changes in either the control context-category or the untrained context-category (see below).

Are there individual differences in generalization?

Visual inspection of the data demonstrated that participants can be grouped into generalizers, non-generalizers, and non-responders based on ES and cross-correlations (see Table 3 for details).

Table 3.

Effect Sizes for Target Items in Each Context-Category and Cross-Correlation Coefficients for Trained and Control Categories

| Trained Category | Untrained Category | Control Category | Cross-correlation Coefficient | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Abstract | Concrete | Abstract | Concrete | Abstract | Concrete | Trained | Control | |

| Generalizers | P1 | 5.82 | 7.01 | 2.78 | 0.94 | 1.83 | 7.18 | 0.65 | 0.15 |

| P3 | 3.46 | 2.31 | 0.00 | −0.58 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 0.52 | 0.04 | |

| P5 | 12.07 | 4.62 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.79 | 0.26 | |

| P6 | 13.79 | 1.73 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 4.62 | 0.57 | 0.53 | −0.28 | |

| P8 | 5.75 | 4.62 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.72 | 0.00 | 0.57 | −0.03 | |

| P10 | 9.24 | 3.46 | −0.58 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 1.73 | 0.57 | 0.31 | |

| P11 | 13.86 | 1.73 | 0.87 | −0.57 | 1.44 | 4.62 | 0.52 | 0.64 | |

| P12 | 4.60 | 2.31 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 1.15 | 0.58 | 0.29 | 0.23 | |

| Non-generalizers | P4 | 17.53 | −0.79 | −0.63 | 1.55 | 0.91 | −2.12 | −0.31 | 0.00 |

| P7 | 12.07 | −0.67 | 0.58 | 0.87 | 0.00 | 0.58 | −0.39 | 0.02 | |

| Non-responders | P2 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 2.24 | −1.79 | 0.16 | −0.62 |

| P9 | 1.15 | −0.44 | 0.00 | −1.15 | 0.00 | 1.73 | −0.22 | CNC | |

Note. Significant values of in bold. Negative values indicated with gray text. CNC = could not complete analysis due to presence of too many zeros.

Generalizers

The largest group (N = 8) consisted of patients who improved on the trained abstract words and also generalized to untrained concrete words in the same context-category. The ESs for these participants ranged from 3.46 to 13.86 (M = 8.57) for the trained abstract words and from 1.73 to 7.01 (M = 3.47) for the untrained concrete words in the same context-category1. The cross-correlations between target abstract and concrete words for these participants were significant for the trained category, indicating a relationship between the two time series, but not for the control category, indicating no relationship between the two time series. Two participants’ (P11 and P12) cross-correlation coefficients for the trained context-category were not significant, but were trending toward significance. Three generalizers (P1, P6, and P11) also showed small to medium generalization ESs for abstract and/or concrete words in either the untrained or the control category. This may be an effect of repetition, since these items were seen by these patients in each treatment session during the category sorting step.

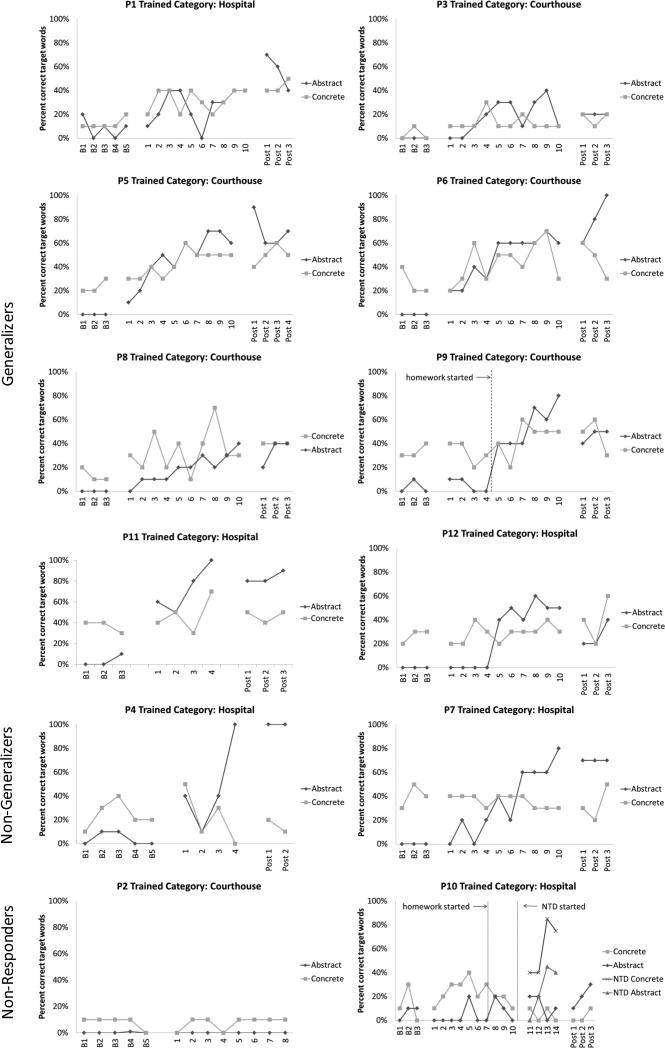

A specific example of a generalizer is P5, who was trained on abstract words in the context-category courthouse for 10 weeks. He showed improvement on trained abstract words from an average of 0% correct at baseline to an average of 70% correct at post-treatment, resulting in a large ES of 12.07. He also showed generalization to untrained concrete words in the same category, increasing from an average of 23% accuracy at baseline to an average of 50% accuracy at post-treatment, resulting in a small ES of 4.62. Cross-correlation for the trained category was .79. See Figure 3 for details.

Figure 3.

Treatment outcomes. This figure illustrates the generative naming probe accuracy throughout treatment for target abstract and concrete words in the trained context-category for all participants. Treatment graphs are organized by generalizers, non-generalizers, and non-responders.

Non-generalizers

Three patients (P4 and P7) improved on the trained abstract words, but did not improve on the untrained concrete words in the same context-category. The ESs for these participants can be found in Table 3. The cross-correlations between target abstract and concrete words for these participants were not significant for either the trained category, indicating that when abstract words improved, concrete words did not, or the control category (see Table 3 for details).

A specific example of a nongeneralizer is P7, who was trained on abstract words in the context-category hospital for 10 weeks. Like P5, he showed an increase in accuracy on trained abstract words from an average of 0% correct at baseline to an average of 70% correct at post-treatment, resulting in an ES of 12.07. However, P7 did not generalize to untrained concrete words in the same category, decreasing from 40% average accuracy at baseline to 30% average accuracy at post-treatment, resulting in an ES of -.67. See Figure 3 for details.

Non-responders

Two patients (P2 and P9) did not improve on either the abstract trained words or the concrete untrained words. The ESs for these participants can be found in Table 3. The cross-correlations between target abstract and concrete words for these participants were not significant for either the trained category or the control category (see Table 3 for details).

A specific example of a non-responder is P9, who was trained on abstract words in the context-category hospital for 14 weeks. He did not improve on either the trained abstract words or the untrained concrete words in the same context-category. After week 7 with no noticeable trend of improvement, we instituted homework which resembled step 5 of treatment and was similar to an untimed probe. Specifically, we asked him to take 5-15 minutes twice per week (once between sessions) to generate as many words as he could think of in the category hospital. Since he had difficulty writing them down, he recorded his responses and emailed the audio file to the clinician. Of 14 opportunities, he completed this homework 11 times, ranging from a 45 second recording with 3 items generated to a 5 minute recording with 20 items generated. He increased his abstract word output to a high of 7 words, which included 3 target items, and his concrete word output to a high of 9 words, which included 2 target items. Unfortunately, these numbers did not transfer to probes conducted during treatment sessions. At week 10, P9 had shown no improvement, so we extended treatment for him to determine whether time was a factor in his case. We also began probing naming to definition to determine if he could show improvement in naming even if he still had trouble generating. After 4 more weeks of treatment, P9 still showed no improvement in generating trained abstract words (ES = 1.15) or untrained concrete words (ES = -0.44) in his trained context-category. Naming to definition improved from 0 to 40% accuracy for trained abstract words and from 40 to 75% accuracy for untrained concrete words. However, note that half credit was given for synonyms or words retrieved after a phonemic cue, indicating an intense need of scaffolding for this patient. See Figure 3 for details.

How does the quality of generative naming responses change after treatment?

In addition to the target abstract and concrete words in each context-category, we recorded all additional responses generated for each context-category. All responses in the first two and last two generative naming probes for each participant for each context-category (trained, untrained, control) were tallied and classified as errors, non-specific responses (not specific to the context-category, but not out of category, e.g., chair), and category-specific responses. Paired t-tests revealed that non-specific responses decreased (t = -4.20, p < .01) and category-specific responses increased (t = 4.17, p < .01) in the trained context-category and non-specific responses decreased in the untrained category (t = -3.38, p < .01). No other comparisons were significant. This shift from non-specific to specific responses may indicate a more focused approach to generative naming after treatment.

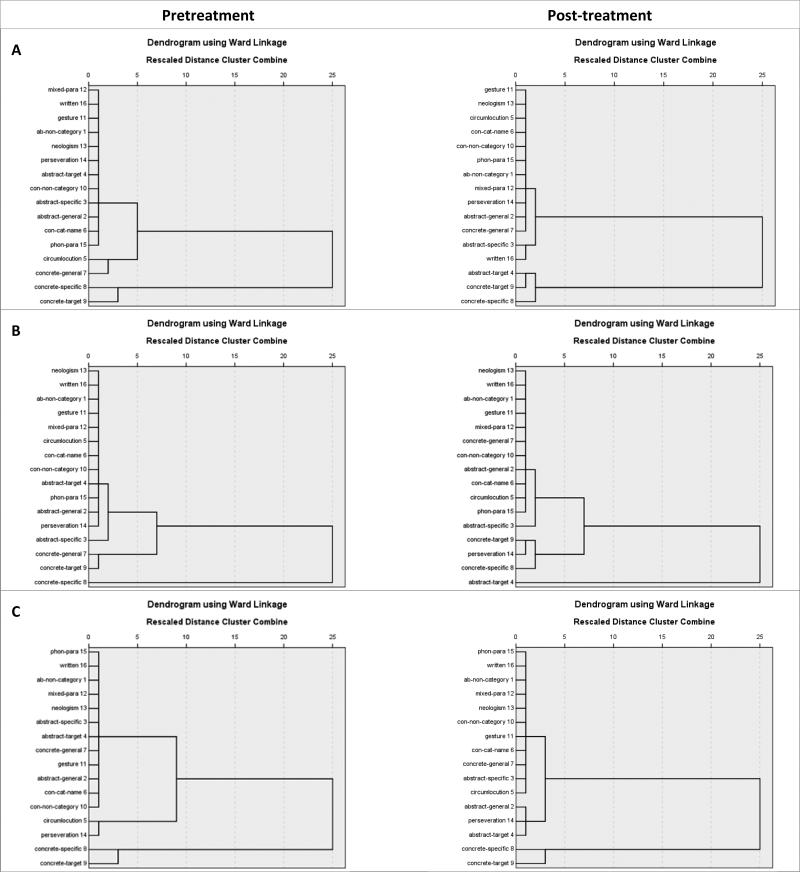

To examine pre- to post-treatment changes in the quality of generative naming responses in the trained context-category more specifically, we performed a hierarchical a cluster analysis. For each patient, all responses for the first two probes and the last two probes were classified by type: target abstract words (abstract-target); target concrete words (concrete-target); abstract words specific to the category (abstract-specific); concrete words specific to the category (concrete-specific); abstract words that are not specific to the category, but are not out of category (abstract-general); concrete words that are not specific to the category, but are not out of category (concrete-general); abstract words that are out of category (ab-non-category); concrete words that are out of category (con-non-category); category name (con-cat-name); perseveration; circumlocution; phonemic paraphasia (phon-para); mixed paraphasia (mixed-para); correct written response (written); correct gesture (gesture); and neologism. The proportion of each type of response was calculated pre- and post-treatment for each participant and these values were entered into a hierarchical cluster analysis in SPSS using Ward’s method applying squared Euclidean Distance as the distance measure. In this way, we obtained a separate dendogram for each time point for the trained context-category for each group (generalizers, non-generalizers, nonresponders) for comparison of pre- to post-treatment patterns of response clustering (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Dendograms of pre- and post-treatment generative response cluster analysis. Panel Aillustrates the clustering of category generation responses before and after treatment for generalizers. Panel B illustrates the clustering of category generation responses before and after treatment for non-generalizers. Panel C illustrates the clustering of category generation responses before and after treatment for non-responders.

Generalizers

Before treatment, generalizers’ responses separate into three clusters: (a) concrete words specific to the context-category, including target concrete words, (b) non-specific concrete words and circumlocutions, and (c) errors and abstract words. After treatment, only two clusters emerge: (a) abstract target words and concrete words specific to the context-category, including target concrete words and (b) all non-specific words, all errors, and specific abstract words. The addition of the abstract target words to the first cluster of concrete words post-treatment reflects the training and generalization seen in treatment. The addition of the non-specific concrete words and circumlocutions to the “error” cluster indicates that generalizers’ responses are becoming more focused and appropriate within the trained context-category after treatment. See Figure 4A for details.

Non-generalizers

Like the generalizers, the non-generalizers’ responses before treatment cluster into three groups: (a) concrete words specific to the context-category, though not including target concrete words, (b) non-specific concrete words and target concrete words, and (c) errors and abstract words. Unlike the generalizers, the non-generalizers’ responses after treatment cluster into three groups: (a) target abstract words, (b) concrete words specific to the context-category, including target concrete words, and perseverations, and (c) errors, non-specific abstract and concrete words, and specific abstract words. The replacement of specific concrete words with target abstract words in the first cluster post-treatment reflects the improvement in word generation for the trained target abstract words without generalization to concrete words in the same category. The addition of specific concrete words and loss of non-specific concrete words to the second cluster after treatment may reflect that these participants are on the verge of becoming generalizers. See Figure 4B for details.

Non-responders

Non-responders’ pre-treatment responses also cluster into three groups, but the membership in these groups is somewhat different: (a) concrete words specific to the context-category, including target concrete words, (b) circumlocutions and perseverations, and (c) other errors, non-specific concrete words, and all abstract words. After treatment, although these participants did not appear to respond to treatment, their responses clustered into different groups where circumlocutions and perseverations joined the second cluster with all the other errors. This suggests that though these patients did not improve on the trained items, they decreased circumlocutions and perseverations, improving the overall quality of their generative naming responses. See Figure 4C for details.

Discussion

In general, treatment was not only effective for the trained abstract words, but also promoted generalization to the untrained concrete words in the same context category. Exceptions to this are the non-generalizers, P4 and P7, who improved on the trained abstract words, but did not generalize to the untrained concrete words, and the non-responders, P2 and P9, who did not improve on either the trained abstract words or the untrained concrete words. Possible reasons for this will be discussed in the next section. Furthermore, the overall quality of responses changed such that after treatment, abstract and concrete words that were specific to the context-category increased while generic responses decreased.

In our previous work (Kiran et al., 2009), we showed that training abstract words in a context-category promoted generalization to concrete words in the same context-category, but not vice versa. In the current study, we examined the effect of training abstract words on generalization to concrete words with a larger group of participants with varying degrees of aphasia type and severity, replicating and extending our findings.

This treatment is based on the CATE, with abstract words being the more complex items and concrete words being the less complex items; therefore, our results lend further support to CATE as a viable theory of generalization in treatment. As mentioned in the introduction, there are several psycholinguistic theories explaining the concreteness effect in both normal and disordered language processing that also help explain why abstract words are more complex than concrete words. As schematized in Figure 1, these theories can be combined into one framework, which may additionally shed some light on the mechanisms underlying the generalization that occurs from abstract to concrete word retrieval in generative naming.

In the Plaut and Shallice (1991) connectionist model, abstract words are defined by fewer semantic features than concrete words. This may be due to the verbal nature of abstract word encoding and the perceptual nature of concrete word encoding as outlined in the DCT (Paivio, 1991). Because this treatment focuses on training semantic features of abstract words, the Plaut and Shallice model would predict the improvement for the generative naming of abstract words. This model would also predict the generalization from abstract to concrete words that shared semantic features. Note, however, that the semantic features that can be shared between abstract and concrete words are limited since there can’t be shared physical attributes or shared taxonomic category. Thus, we can posit that participants who did not generalize were not able to recognize which features were shared between abstract and concrete words.

If we additionally take into consideration the NICE model (Newton & Barry, 1997), another mechanism for generalization from abstract to concrete words becomes apparent. In this model, abstract words are loosely associated with many different concepts in the semantic network and produce more spreading activation than concrete words, which have strong and specific associations, making concrete words more easily retrieved. As Kiran et al. (2009) suggested, these differences in semantic representation may make abstract words better targets in therapy because training abstract words is thought to strengthen the activation which is thought to, in turn, spread to all associated words, both abstract and concrete. However, this effect could be weak and short-lived due to the diversity of connections for abstract words. On the other hand, when the context is constrained and made salient for the abstract words (Schwanenflugel et al., 1988), as is the case with the current treatment paradigm, spreading activation to words in the trained context-category is reinforced. In this scenario, participants who do not generalize may have damage to the connections between abstract and concrete concepts. These connections may need to be explicitly trained to promote generalization.

An additional theory that supports the idea of generalization within context-categories is perceptual symbol systems (Barsalou, 1999). Barsalou suggests that all concepts (i.e., perceptual symbols) are modal in nature and that while concrete concepts are encoded through the senses, abstract concepts are encoded through a combination of physical events and introspection. Both abstract and concrete concepts are retrieved through partially reproducing perceptual experiences (simulations) of contact with those concepts. We can imagine that when abstract concepts are partially simulated, related concrete concepts would necessarily be simulated. Of particular interest is the instruction for the probes in which the clinician would explicitly ask the patient to imagine being in, for example, a hospital in order to facilitate generative naming within that context-category. Before treatment, patients often produced mainly people and things that would be seen in a hospital room, such as nurse and bedpan. When patients were trained on abstract concepts like diagnosis using semantic features such as “requires specific equipment,” specific equipment such as MRI and stethoscope begin to be produced during probes, possibly due to the participant remembering their own experience being diagnosed or imagining a scenario where a diagnosis is being made. Participants who did not generalize in treatment (and those who did not respond to treatment at all) may have had trouble simulating a scenario for an abstract concept. However, this is purely conjecture and would need to be systematically tested.

The results of this study are consonant with existing theories of abstract and concrete word processing. Taken together, these theories contribute plausible mechanisms for the generalization effect between abstract and concrete words observed with this treatment. Further research is needed to tease apart the exact mechanism that is supporting generalization. In so doing, it may be possible to also explain why some participants who show a treatment effect do not show a generalization effect.

Quality of Responses

We hypothesized that generative responses to each context-category in general would become more focused and appropriate as a result of treatment – as subjectively noted in Kiran et al. (2009), but not objectively measured. We found this to be true. In the trained context-category, non-specific responses decreased while category-specific responses increased. Looking at specific responses in the trained context-category, we found that all three groups showed a shift in the clustering of responses from pre- to post-treatment; however the pattern of change was different for each group and reflected treatment outcomes. Generalizers shifted from a main cluster of concrete words before treatment to a main cluster of abstract and concrete words after treatment, reflecting training and generalization effects seen in treatment. Non-generalizers shifted from a main cluster of concrete words before treatment to a main cluster of trained abstract words, with a secondary cluster of concrete words. This reflects the training effects without generalization effects, but may also indicate the possibility of eventual generalization to concrete words given more time. Non-responders shifted from a main cluster of concrete words, with a secondary cluster of circumlocutions and perseverations before treatment, to a main cluster of concrete words after treatment. This reflects the lack of response to trained items, but also suggests some refinement of responses, possibly simply due to practice with the task. In all three groups, non-specific abstract and concrete words, circumlocutions, and perseverations all joined the “error” cluster after treatment, indicating a shift from an unfocused approach to generative naming to a more accurate and focused approach across participants after treatment. Perhaps repeated exposure to the trained context-category, thinking about not only the concepts within that context but also the semantic features of the concepts and how the concepts interact within the context, helped the participants to increase their specificity of responses.

Differences in Patient Outcomes

Ten of the 12 participants improved on the trained abstract words; however, two participants did not respond to treatment. This could be due to the fact that one of the non-responders had the lowest WAB AQ (41.7), the lowest BNT score (22%), and was the only participant with Broca’s aphasia, exhibiting markedly limited verbal output. The other non-responder had a relatively high AQ (82.2) and BNT (82%), but severe cognitive deficits according to the CLQT and impaired semantic processing according to the PAPT (75%). It is therefore possible that this particular treatment may not be well suited for patients with these characteristics.

Of the ten participants who improved on the trained abstract words, eight also showed improvement on the untrained concrete words in the same context-category. It is difficult to pinpoint the reason that two participants who showed improvement for the trained abstract words did not generalize to untrained concrete words in the same context-category because there are no aspects of their demographic and linguistic profile that do not match with at least one generalizer's demographic and linguistic profile. Importantly, these participants improved on the trained abstract words. Therefore, whatever is blocking them from generalizing is not related to direct training. Indeed, the cluster analysis suggests that these participants may have been on the verge of becoming generalizers. It is possible that a more intensive therapy schedule would benefit these participants (Cherney, Patterson, Raymer, Frymark, & Schooling, 2008).

Conclusion

Ten of the 12 participants improved on the trained items, resulting in an 83% success rate for this study, suggesting that this treatment is efficacious for participants with a variety of aphasia types and severities. Furthermore, of the ten participants who showed treatment effects, eight also showed generalization. These findings replicate and extend the results of Kiran et al. (2009) to a larger group of participants with a wider variety of aphasia types and severities. Taken together, these studies show that training abstract words in a generative naming treatment is not only efficacious, but also efficient because it promotes generalization to concrete words in the same context-category for a majority of participants.

For the participants for whom the treatment was not efficacious, moderate to severe linguistic and/or cognitive deficits appear to be to blame. However, the small number of non-responders makes a definitive claim impossible. For participants who did not show generalization, there are no distinguishing demographic or linguistic traits that separate them from those who did show generalization. A more thorough analysis of how abstract and concrete words are processed by these participants and studies that are specifically designed to test how current theories of abstract and concrete word processing apply to generalization in treatment may be helpful. Additionally, increasing the length or intensity of treatment may help these participants to generalize. Clearly more work is needed in this area of treatment research.

Appendix

Appendix A.

Words and Features Used in Treatment

| Courthouse | Hospital | Church | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abstract | Concrete | Abstract | Concrete | Abstract | Concrete |

| guilt | bench | admission | ambulance | angel | bell |

| justice | case | care | bandage | baptism | Bible |

| law | flag | condition | blood | belief | candle |

| oath | gavel | diagnosis | chart | blessing | chapel |

| pardon | judge | emergency | doctor | forgiveness | hymn |

| perjury | jury | health | medication | grace | minister |

| plead | lawyer | mortality | nurse | holy | organ |

| proof | prison | recovery | patient | penance | parish |

| sue | record | sterile | stethoscope | prayer | steeple |

| truth | robe | treatment | syringe | solace | wedding |

| Generic Features | |

| exists only in the mind | has a physical presence |

| exists outside the mind | an object |

| can be seen | is alive |

| can be heard | a feeling or emotion |

| can be touched | an idea |

| can be tasted | generally considered positive |

| can be perceived | generally considered negative |

| different meaning for different people | |

| Unrelated Features | |

| builds a nest | comes out of a cocoon |

| has feathers | spins a web |

| lives in trees | is crunchy |

| is poisonous | lives in the water |

| is furry | grows in soil |

| is put on windows | has six feet |

| used to cut paper | used to plow the fields |

| made of leather | |

| Examples of Patient-Generated Features | |

| Courthouse | recovery – affected by quality of hospital |

| sue – can be frivolous | health – associated with diet and exercise |

| plead – can be coerced | treatment – gives you hope |

| law – maintains order | |

| pardon – can be suspicious | |

| Hospital | |

| emergency – can cause anxiety |

Appendix B. Treatment Protocol

Steps 1 and 5 are completed only once per session. Steps 2-4 are completed for each word. The amount of support provided to patients is adjusted based on the patients’ ability and progression through treatment.

Category Sorting. This step is performed only once at the beginning of each session. Using E-Prime, 40 words (10 abstract and 10 concrete from each category) are presented in random order. One category is the target category (hospital, courthouse), the other category is the distractor category, church. The label for each category is presented at the bottom of the screen. The patient presses number 3 for the left option and number 4 for the right option. The left option is always the target category and the right option is always church. The word to be sorted appears at the center of the screen. The patient has unlimited time to make the choice. After the choice is made, a green checkmark provides feedback that the choice was correct; a red X provides feedback that the choice was incorrect. The program records accuracy and reaction time. Note that P1-P5 performed this step using words printed on cardstock and sorted 60 words (10 abstract and 10 concrete from each category) into their respective categories (hospital, courthouse, church). Feedback was provided.

- Feature Selection. The patient is given a word card from the target category (e.g., emergency) and asked to read the word. If needed, the clinician models the word. The clinician then presents the patient with the written feature cards of the target category (e.g., hospital) and asks the patient to select the first 6 semantic features that fit with emergency. If the patient appears to be struggling with the task of choosing features, the clinician goes through each of the feature cards with the patient. For example, “Is emergency an object? No? Then we’ll reject it.” “Is emergency an idea? Yes? Then let's keep it.” If the patient picks a feature card that is not obviously well-fitting of the word, the clinician asks the patient to explain why that feature applies to that word. If the patient cannot provide an explanation, the clinician provides an argument for and against that feature and asks the patient which argument s/he agrees with. Once six features have been selected, the clinician asks the patient to read aloud the features that have been selected in sentence form (e.g., “Emergency is an idea. Emergency is generally considered negative.”). The clinician may read the features aloud if the patient struggles, fading cues as treatment progresses. The clinician should make sure that the patient browses all of the features during each session so that the same features aren't continually relied upon.

- During the first treatment session, rather than feature selection, the clinician and patient brainstorm features for each word so the patient has some personally relevant features to choose from. The clinician says something like “We’re going to work on the characteristics/features of some of the words from the category ‘hospital’. One of the characteristics/features of words is whether they are abstract or concrete. Abstract words are thoughts, ideas, or feelings that can't be touched, seen, tasted, etc., like the word ‘knowledge’. Concrete words are things or objects that can be seen, touched, etc., like the word ‘chair’. Do you have any questions? Now, tell me about an ‘emergency’.” The clinician can provide leading questions to assist the patient.

Yes/No Questions: After feature selection, the clinician removes the word and feature cards and tell the participant “Now I’m going to ask you some questions about the word ‘emergency’. Please answer yes or no for each of these questions.” The clinician asks the patient 15 questions for each target word: 5 that are acceptable semantic features, 5 that are unacceptable semantic features from the same category, and 5 that are semantic features from a different category. For the example word emergency, “(a) Is it an idea? (b) Does it have a practical use? (c) Does it have shelves?” If the patient answers incorrectly, the clinician asks the patient to think about it and make sure it is the correct response. The question may be reworded and/or a short explanation may be provided to assist in comprehension. For example, if the clinician asks “Does it have shelves?” and the patient does not seem to understand or says “yes,” then the clinician may ask “Does an emergency have shelves?” or “Is an emergency a thing that can have shelves?”

Recall, Synonym, Type: After the patient has answered all of the yes/no questions for that word, the clinician asks if it is an abstract word or a concrete word, reiterating the definitions of abstract and concrete, if necessary. The clinician provides feedback and repeats the correct response. Then the clinician asks the patient for a synonym. The target word may be repeated, if asked. If the patient can't think of a synonym, the clinician provides a multiple choice or fill-in-the-blank (e.g., “What means the same thing as emergency, crisis or decision?). Finally, the clinician asks the patient to recall the target word and feedback on accuracy is provided.

Free Generative Naming: This step is performed only once at the end of each session with only the target category. This step has no time limit, but is usually from 5 to 15 minutes long. The clinician asks the participant, “List as many words as you can think of that are associated with the category ‘hospital’. You may list either concrete or abstract words. Think of all of the words we worked on today as well as others that belong to this category.” The clinician provides feedback regarding the accuracy of responses. For example, “Yes, emergency definitely goes with hospital.” or “No, baseball doesn't have anything to do with a hospital. It's more related to sports.” If the patient is struggling, the clinician can prompt them. For example, “You said emergency, now what do you think of when you think of an emergency?”

Appendix C. Testing Protocol for Generative Naming

During baseline, 3-5 probes are given. After baseline, a treatment probe is given every other treatment session at the beginning of the session, so that there are 2 treatments between each probe. After treatment, 3 post-treatment probes are given.

The clinician asks the patient to “List as many words as you can think of that are associated with the category X (e.g., hospital, courthouse). List both concrete words, such as things or people and abstract words, such as ideas and feelings. For example, for the category school you could say teacher or you could say knowledge.” The patient is allowed two minutes for generative naming. The clinician writes down every word the patient provides. If patient does not respond within 20 seconds, the clinician may prompt, saying something like “Give it your best guess.” If the patient starts to provide a story-like response, the clinician prompts for single words. The clinician may provide only general encouragement (e.g., “You’re doing fine.”), but may not give specific feedback regarding accuracy of responses.

Each correct response receives 1 point and each incorrect response receives 0 points. A response is counted as correct when:

The response is clear and intelligible and is the target or a close synonym (e.g. evidence for proof)

The subject produces approximations of the target and then achieves the target

The response is a variation of the target, as long as the meaning is not changed (e.g., guilty for guilt)

Dialectal differences

At a request for clarification by the experimenter, the subject is able to produce the target accurately

Distortion/substitution of a phoneme (e.g., crucipix for crucifix)

A response is counted as incorrect when:

The response is a neologism, meaning that less than 50% of the word resembles the target (e.g., rodifer for doctor)

The response has the same root word as the target, but a different meaning (e.g., believer for belief). Although, this may be counted as a correct ‘other’ word.

The response is a circumlocution (e.g., ‘12 people’ for jury) 4. The response is a phonemic paraphasia (e.g., procetshusor for prosecutor) 5. The category is given as the response (e.g., children's hospital cannot be counted as other acceptable responses for the category hospital)

An unrelated word out of the category (e.g., dentist for the category courthouse) 7. No response or I don't know

Any response that is not a pre-selected target may be counted as a correct ‘other’ response if it fits reasonably within the category. For example, both table and defendant may be counted correct for courthouse, although neither are designated ‘targets’ for the category (see Appendix A). Table would be considered a generic response, while defendant would be a category-specific response.

Footnotes

Note that although the lower values of these ranges are below the small effect size cutoff according to Beeson and Robey (2006, 2008), the cutoffs are based on confrontation naming, not generative naming, and are therefore used here as loose guidelines.

References

- Barry C, Gerhand S. Both concreteness and age-of-acquisition affect reading accuracy but only concreteness affects comprehension in a deep dyslexic patient. Brain Lang. 2003;84(1):84–104. doi: 10.1016/s0093-934x(02)00522-9. doi: S0093934X02005229 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsalou LW. Perceptual symbol systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1999;22(04):577–660. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x99002149. doi: doi:null. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeson PM, Robey RR. Evaluating single-subject treatment research: Lessons learned from the aphasia literature. Neuropsychology Review. 2006;16(4):161–169. doi: 10.1007/s11065-006-9013-7. doi: 10.1007/s11065-006-9013-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeson PM, Robey RR. Paper presented at the Clinical Aphasiology Conference. Jackson Hole; WY.: 2008. Meta-analysis of aphasia treatment outcomes: Examining the evidence. [Google Scholar]

- Bleasdale FA. Concreteness-dependent associative priming: Separate lexical organization for concrete and abstract words. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1987;13(4):582–594. [Google Scholar]

- Cherney LR, Patterson JP, Raymer A, Frymark T, Schooling T. Evidence-based systematic review: Effects of intensity of treatment and constraint-induced language therapy for individuals with stroke-induced aphasia. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 2008;51(5):1282–1299. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/07-0206). doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/07-0206) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AM, Loftus EF. A spreading-activation theory of semantic processing. Psychological Review. 1975;82(6):407–428. [Google Scholar]

- Crutch SJ, Warrington EK. Abstract and concrete concepts have structurally different representational frameworks. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 3):615–627. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh349. doi: awh349 [pii] 10.1093/brain/awh349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot AM. Representational aspects of word imageability and word frequency as assessed through word association. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning. Memory, and Cognition. 1989;15(5):824–845. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot AM, Keijzer R. What is hard to learn is easy to forget: The roles of word concreteness, cognate status, and word frequency in foreign-language vocabulary learning and forgetting. Language Learning. 2000;50(1):1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds LA, Kiran S. Effect of semantic naming treatment on crosslinguistic generalization in bilingual aphasia. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 2006;49(4):729–748. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/053). doi: 49 /4/729 [pii] 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/053) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilhooly KJ, Logie RH. Age of acquisition, imagery, concreteness, familiarity and ambiguity measures for 1944 words. Behavior Research Methods and Instrumentation. 1980;12:395–427. [Google Scholar]

- Goodglass H, Kaplan E, Weintraub S. Boston naming test. Lea & Febiger; Philadelphia: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Helm-Estabrooks N. Cognitive linguistic quick test. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Howard D, Patterson K. The pyramids and palm trees test. Thames Valley Test Company; Bury St. Edmunds: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- James CT. The role of semantic information in lexical decisions. Journal of Experimental Psychology (Human Perception and Performance) 1975;104(2):130–136. [Google Scholar]

- Jones GV. Deep dyslexia, imageability, and ease of predication. Brain Lang. 1985;24(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(85)90094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay J, Lesser RP, Coltheart M. The psycholinguistic assessment of language processing in aphasia (palpa) Erlbaum; Hove, UK: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz A. Western aphasia battery - revised (wab-r): Harcourt Assessment, Inc. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Beaudoin-Parsons D. Training phonological reading in deep alexia: Does it improve reading words with low imageability? Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics. 2007;21(5):321–351. doi: 10.1080/02699200701245415. doi: 777792763 [pii] 10.1080/02699200701245415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiran S. Complexity in the treatment of naming deficits. American Journal of Speech Language Pathology. 2007;16(1):18–29. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2007/004). doi: 16/1/18 [pii] 10.1044/1058-0360(2007/004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiran S. Typicality of inanimate category exemplars in aphasia treatment: Further evidence for semantic complexity. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 2008;51(6):1550–1568. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/07-0038). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiran S, Abbott KP. Effect of abstractness on treatment for generative naming deficits in aphasia. Brain and Language. 2007;103(1-2):92–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kiran S, Bassetto G. Evaluating the effectiveness of semantic-based treatment for naming deficits in aphasia: What works? Seminars in Speech and Language. 2008;29(1):71–82. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1061626. doi: 10.1055/s-2008 -1061626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiran S, Roberts PM. Semantic feature analysis treatment in spanish-english and french-english bilingual aphasia. Aphasiology. 2010;24(2):231–261. [Google Scholar]

- Kiran S, Sandberg C. Chapter 14 - treating communication problems in individuals with disordered language. In: Peach R, Shapiro L, editors. Cognition and acquired language disorders. Mosby; Saint Louis: 2012. pp. 298–325. [Google Scholar]

- Kiran S, Sandberg C, Abbott K. Treatment for lexical retrieval using abstract and concrete words in persons with aphasia: Effect of complexity. Aphasiology. 2009;23:835–853. doi: 10.1080/02687030802588866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiran S, Sandberg C, Sebastian R. Treatment of category generation and retrieval in aphasia: Effect of typicality of category items. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2011;54(4):1101–1117. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/10-0117). doi: 1092-4388_2010_10-0117 [pii] 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/10-0117) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiran S, Thompson CK. The role of semantic complexity in treatment of naming deficits: Training semantic categories in fluent aphasia by controlling exemplar typicality. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 2003;46(3):608–622. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/048). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiran S, Tuchtenhagen J. Imageability effects in normal spanish-english bilingual adults and in aphasia: Evidence from naming to definition and semantic priming tasks. Aphasiology. 2005;19(3):315–327. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss GR, Armstrong C, Milroy R, Piper J. An associative thesaurus of english and its computer analysis. In: Aitken AJ, Bailey RW, Hamilton-Smith N, editors. The computer and literary studies. University Press; Edinburgh: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Martin N, Saffran EM. Language and auditory-verbal short-term memory impairments: Evidence for common underlying processes. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 1997;14(5):641–682. doi: 10.1080/026432997381402. [Google Scholar]

- Martin N, Saffran EM. Effects of word processing and short-term memory deficits on verbal learning: Evidence from aphasia. International Journal of Psychology. 1999;34(5-6):339–346. doi: 10.1080/002075999399666. [Google Scholar]

- Martin N, Saffran EM, Dell GS. Recovery in deep dysphasia: Evidence for a relation between auditory - verbal stm capacity and lexical errors in repetition. Brain and Language. 1996;52(1):83–113. doi: 10.1006/brln.1996.0005. doi: S0093-934X(96)90005-X [pii] 10.1006/brln.1996.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau SE, Kendall D. Significance and possible mechanisms underlying generalization in aphasia therapy: Semantic treatment of anomia. Brain and Language. 2006;99:8–219. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2006.06.016. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DL, Mcevoy CL, Schreiber TA. The university of florida word association, rhyme, and word fragment norms. 1998 doi: 10.3758/bf03195588. from http://www.usf.edu/FreeAssociation/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- Newton PK, Barry C. Concreteness effects in word production but not word comprehension in deep dyslexia. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 1997;14:481–509. [Google Scholar]

- Nickels L, Howard D. Aphasic naming: What matters? Neuropsychologia. 1995;33(10):1281–1303. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(95)00102-9. doi: 0028-3932(95)00102-9 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paivio A. Dual coding theory: Retrospect and current status. Canadian Journal of Psychology. 1991;45(3):255–287. [Google Scholar]

- Plaut DC, Shallice T. Effects of word abstractness in a connectionist model of deep dyslexia. Paper presented at the 13th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. 1991 [Google Scholar]

- Renvall K, Nickels L, Davidson B. Functionally relevant items in the treatment of aphasia (part i): Challenges for current practice. Aphasiology. 2013;27(6):636–650. doi: 10.1080/02687038.2013.786804. [Google Scholar]

- Schwanenflugel PJ, Harnishfeger KK, Stowe RW. Context availability and lexical decisions for abstract and concrete words. Journal of Memory and Language. 1988;27(5):499. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson C. Complexity in language learning and treatment. American Journal of Speech Language Pathology. 2007;16(1):3–5. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2007/002). doi: 16/1/3 [pii] 10.1044/1058-0360(2007/002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson C, Shapiro L, Kiran S, Sobecks J. The role of syntactic complexity in treatment of sentence deficits in agrammatic aphasia: The complexity account of treatment efficacy (cate). Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 2003;46(3):591–607. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/047). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]