Abstract

Objective

The glands of the stomach body and antral mucosa contain a complex compendium of cell lineages. In lower mammals, the distribution of oxyntic glands and antral glands define the anatomical regions within the stomach. We examined in detail the distribution of the full range of cell lineages within the human stomach.

Design

We determined the distribution of gastric gland cell lineages with specific immunocytochemical markers in entire stomach specimens from three non-obese organ donors.

Results

The anatomical body and antrum of the human stomach were defined by the presence of ghrelin and gastrin cells, respectively. Concentrations of somatostatin cells were observed in the proximal stomach. Parietal cells were seen in all glands of the body of stomach as well as in over 50% of antral glands. MIST1-expressing chief cells were predominantly observed in the body, although individual glands of the antrum also showed MIST1-expressing chief cells. While classically-described antral glands were observed with gastrin cells and deep antral mucous cells without any parietal cells, we also observed a substantial population of mixed-type glands containing both parietal cells and G cells throughout the antrum.

Conclusions

Enteroendocrine cells show distinct patterns of localization in the human stomach. The existence of antral glands with mixed cell lineages indicates that human antral glands may be functionally chimeric with glands assembled from multiple distinct stem cell populations.

Keywords: parietal cells, chief cells, somatostatin, gastrin, ghrelin, serotonin, MUC6, Mist1, ECL cells, SOX2, tuft cell, tissue arrays

INTRODUCTION

Among gastrointestinal tissues, the gastric mucosa is constructed from a more complex set of short-lived and long-lived cell lineages [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. While studies over the past 20 years have detailed the origin and distribution of cell lineages in the rodent stomach [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], far fewer studies have addressed the distribution of lineages in the human stomach. The rodent stomach is divided into three discrete anatomical zones including the squamous-lined forestomach, the glandular-oxyntic (body) region containing acid-secreting parietal cells and pepsinogen-secreting chief cells and the antrum containing gastrin cells [6]. In all rodents studied as well as other mammalian species, the border between the antrum and the body contains areas of transitional glands with fewer parietal cells before the initiation of antral mucous glands that lack parietal cells [6, 7]. It is thought that the boundaries between these regions are dictated by the developmental expression of specific transcription factors, especially SOX2 and PDX1 [8, 9]. Thus, PDX1 expression defines the region of rodent antrum and deletion of PDX1 causes a failure of antrum formation [10].

In contrast with mice, the geographic anatomy of the human stomach is far less detailed. The human stomach does not have a squamous forestomach region, but rather is divided anatomically into three regions: a proximal peri-esophageal cardia, the glandular body and the antrum [11]. Traditionally, these regions have been grossly defined by the positions of the nerves of Latrajet. While much of the present literature suggests that human gastric lineages are distributed in a manner similar to that in rodents and other animals, few studies have previously defined in detail the distribution of cell types within the human stomach.

We have now evaluated the geographic distribution of cell lineages within the human stomach by quantitative determination of cell numbers throughout the gastric mucosa from non-obese organ donors. These results have revealed that cell lineages are not uniformly distributed throughout the stomach and that there are distinct and important differences in human compared with other species. Enteroendocrine cell lineages were concentrated in discrete regions within the proximal and distal stomach. Ghrelin and gastrin best defined the anatomical body and antrum, respectively. Importantly, parietal cells were distributed in glands throughout the human antrum. Indeed, the human antrum appears to contain three distinct types of glands containing 1) parietal and chief cells (oxyntic-type glands), 2) gastrin and TFF2-positive mucous cells (antral-type glands), as well as 3) both parietal cells and gastrin cells (mixed-type glands). The results suggest that the human stomach has a unique geographical distribution of lineages with acid secreting cells throughout the antrum. These findings suggest that lineage derivation in human stomach may not follow the same rules as in mouse stomach.

METHODS

See Supplemental Methods.

RESULTS

Mapping the geographic distribution of lineages in the human stomach

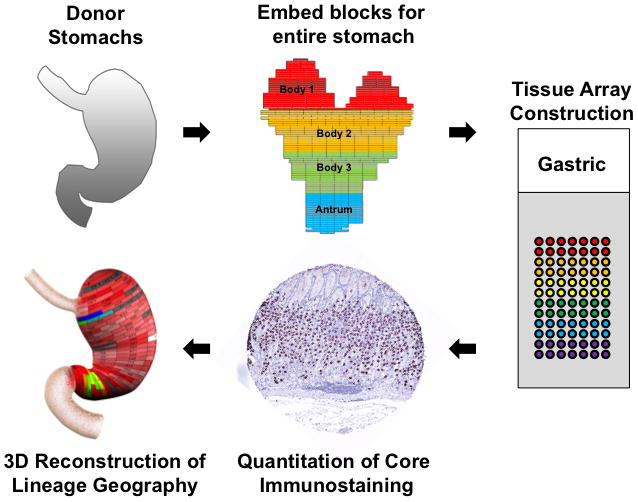

To map the distribution of cell lineages within the human stomach, the entire stomach was obtained from three organ donors (Table 1). The stomachs were opened along the greater curvature and fixed overnight in formalin. The specimens were then divided into regions of 0.5 cm height X 2 cm wide (Figure 1). Each region was separately embedded in paraffin with the specimen oriented to display glands along their length. One millimeter cores from these blocks were then excised and arrayed into tissue arrays that together covered the entire stomachs from the three specimens. We then stained these arrays with antibodies against specific markers of cell lineages (Table 2). The tissue arrays were analyzed by digital quantitation using an Ariol SL-50 system (Leica) and lineage abundance was quantified as cells per 1 mm core (Figure 1). The cell numbers were then displayed in two dimensions on maps of the stomach specimen (Supplemental Figures 1–3) and heat map coloration was developed to display the data. Finally, the 2-dimensional maps were rendered onto 3-dimensional projections of the stomach to display the distribution of lineages throughout the stomachs. Data for all three of the donor stomachs are shown in the Supplemental Materials as 2-dimensional maps (Supplemental Figures 1–3). 3-dimensional rendering was performed only for the Donor 2 stomach as representative of our findings (Figures 2 and 3). Dynamic rotating reconstructions of the 3-dimensional renderings are included in Supplemental Videos 1–9. To analyze the distribution of lineages in the stomachs, each specimen was divided into three body zones and antrum (see Figure 1) and the distributions of lineages were analyzed as a percent of total labeled cells (Figure 4).

Figure 1. Procedure for geographic mapping of the cell lineages within the human stomach.

The three entire donor stomachs were divided into regions of 0.5 cm height X 2 cm wide to embed in paraffin blocks and 1 mm cores from the paraffin blocks were excised and assembled into tissue arrays. These arrays were stained with cell lineage-specific antibodies, and then the cell numbers per core were determined using a digital quantitation system (Ariol SL-50). Finally, the distribution of cell lineages was displayed in three-dimensional projections of the stomach.

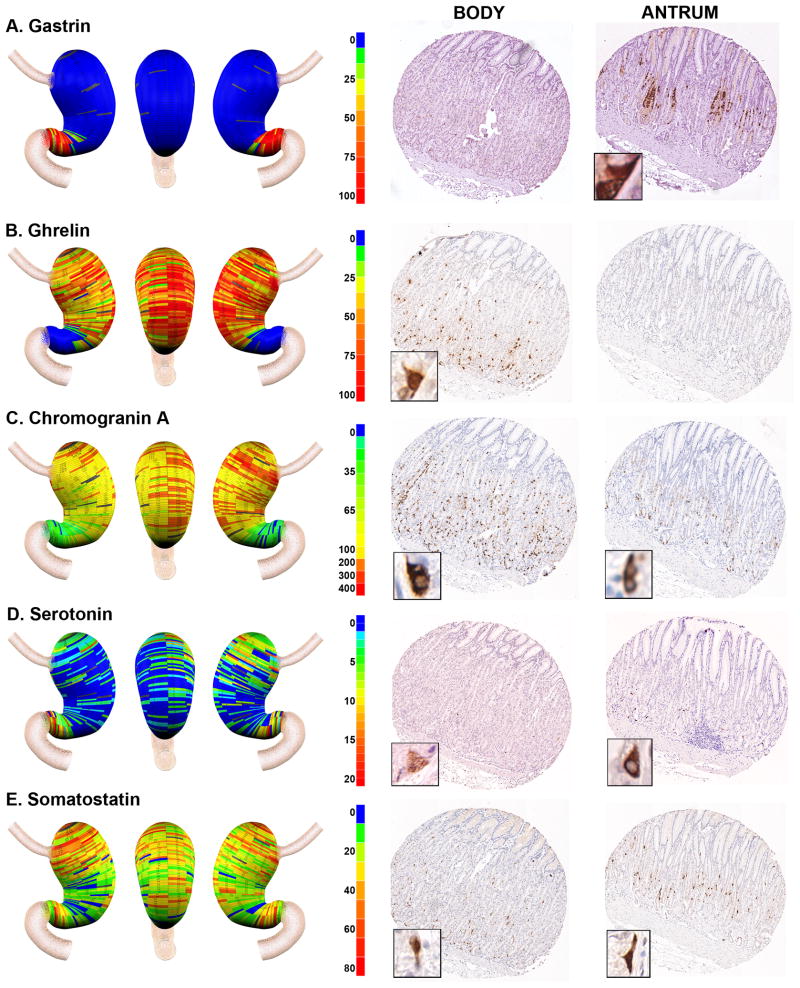

Figure 2. Geographic mapping of endocrine cell lineages.

Tissue array sections from Donor 2 were stained for A. Gastrin (G cells), B. Ghrelin (X cells), C. Chromogranin A (enteroendocrine cells), D. Serotonin (EC cells) and E. Somatostatin (D cells). Quantitated cell lineage numbers per core were mapped onto three dimensional stomach maps to demonstrate the distribution of cells in the stomach (left panels). The scale bars represent the range of positive cells in a core. Representative cores from the body and antrum are shown at the right of each panel with high magnification insets showing the individual cell staining pattern.

Figure 3. Geographic mapping of progenitor and oxyntic gland cell lineages.

Tissue array sections were stained for A. Ki-67 (progenitor cells), B. H/K-ATPase (parietal cells), C. Mist1 (chief cells) and D. Muc6 (mucous neck cells and deep antral gland cells). Quantitated cell lineage numbers per core were mapped onto three dimensional stomach maps to demonstrate the distribution of cells in the stomach (left panels). The scale bars represent the quantitated range of positive cells in a core. Representative cores from the body and antrum are shown at the right of each panel with high magnification insets showing the individual cell staining pattern. In the antral core for MUC6 staining in D, insets show the staining for cells with mucous neck cell morphology at left and cells with deep antral gland cell morphology at right.

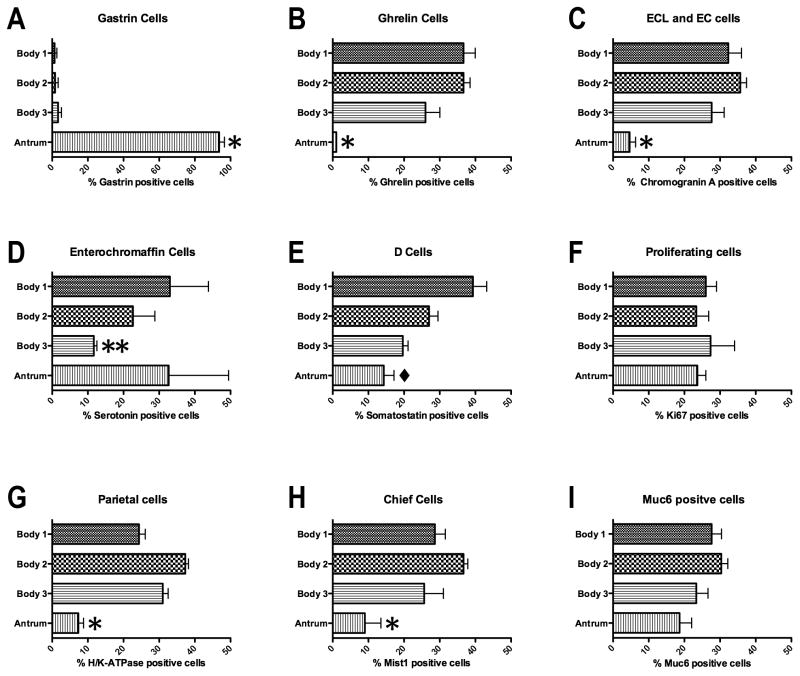

Figure 4. Quantitation of the distribution of cell lineages in the human stomach.

To quantitate the distribution of cell lineages within the human stomachs the specimens were divided into three body regions (proximal to distal): Body 1 (B1), Body 2 (B2) and Body 3 (B3) and the antrum. The numbers of cells staining for each lineage in each zone were determined as a percentage of the total labeled cells in each stomach specimen. The percentages of labeled cells in each region were compared with ANOVA and Bonferroni’s test for significant means. *p<0.05 between the antrum and all three Body regions; **p<0.05 comparing antrum to B1 and B2; ◆p<0.05 comparing B3 with both B1 and antrum. All bars represent the mean ± SEM.

Distribution of enteroendocrine cells in the human stomach

Traditionally, the gastric regions of the human stomach have been divided into body versus antral regions. We therefore examined the distribution of enteroendocrine cell lineages in the glands of these regions. As noted in numerous previous investigations [12, 13, 14, 15], gastrin-expressing cells were confined to the distal stomach (Figures 2A and 4A). In contrast, also as previously reported [16], ghrelin-expressing cells were essentially excluded from the distal stomach and were abundant in the the stomach body regions with a relatively even distribution throughout the body mucosa (Figures 2B and 4B). A similar staining pattern was also observed for obestatin, a splice variant of the ghrelin gene (data not shown) [17]. This inverse relationship between gastrin and ghrelin expression was observed in all three of the donor stomachs (Supplemental Figure 1 and Figure 4A,B). These findings suggested that gastrin and ghrelin cells define the anatomical division between the human stomach body and antrum, respectively.

Given the asymmetric distribution of ghrelin and gastrin cells, we evaluated the distribution of other cell lineages within the three zones of the gastric body and the fourth zone of the antrum. These distributions were evaluated across all three organ donor stomach specimens (Figure 4). We first examined the distribution of other enteroendocrine cells in the stomach. Chromogranin A is prominently expressed in most amine-secreting enteroendocrine cells, including the histamine-secreting ECL cells [18, 19]. Figures 2C and 4C demonstrate that chromogranin A-positive cells were numerous and uniformly distributed throughout the anatomic body of the stomach defined by the ghrelin-expressing cells. Significantly lower numbers of chromogranin A-immunoreactive cells were also seen in the anatomic antrum. We next determined the distribution of serotonin expressing enterochromaffin cells in the stomach. Serotonin cells were far less numerous throughout the stomach, usually fewer than 10 cells per core. Compared with other markers, there was more variability in both serotonin cell numbers and distribution. Similar to findings in a previous report [20], all three donor stomachs showed a concentration of serotonin cells in the antrum (Figures 2D and 4D). However, we also observed a concentration of serotonin cells in the proximal stomach.

To complete an analysis of enteroendocrine cells in the human stomach, we examined the distribution of somatostatin-immunoreactive D cells. D cells were distributed throughout the body and antrum (Figure 2E). In all three stomachs, there were significantly higher numbers of somatostatin cells in the proximal regions of the body mucosa (Figure 4E). Thus, the inhibitory influences of somatostatin cells are concentrated in the proximal stomach [21].

In addition to the endocrine cell lineages, we also evaluated the presence of tuft cells in the normal human stomachs. The tuft cells are sensory mucosal cell lineages that form direct synapses with interneurons in the gastric wall [5]. Staining for DCLK1, a marker of tuft cells, showed staining of rare individual cells in cores in the body and antrum (Supplemental Figure 4B). The tufts cells showed the characteristic morphology with a prominent apical extension (Supplemental Figure 4B). The tuft cells were extremely rare and no more than 20 tufts cells were identified in an entire set of stomach specimen cores.

Distribution of mucous and secretory lineages in the human stomach

We next examined the distribution of cells considered components of oxyntic glands: surface mucous cells, parietal cells, chief cells and mucous neck cells. We did not strictly quantify surface mucous cell numbers because the staining for either MUC5AC or Diastase-resistant PAS was so intense and the cell borders were difficult to discern (data not shown). Supplemental Figure 4A demonstrates that MUC5AC-staining surface cells were prominent in cores from both the body and antral regions, but the length of foveolar regions was greater in the antral cores.

We evaluated the presence of proliferating cells using Ki-67 staining (Figure 3A). As expected, in the body of the stomach Ki-67-expressing progenitor cells were located in the upper gland region deep to the foveolar cells. Similarly, in the antrum, Ki-67-expressing cells were present in the mid-gland deep to the foveolar cells. Overall, the analysis of the distribution of Ki67-expressing progenitor cells demonstrated a relatively uniform distribution of proliferative cell numbers throughout the gastric mucosa (Figure 4F).

H/K-ATPase staining, as expected, demonstrated large numbers of parietal cells throughout the anatomic body in all three stomachs, with 95% of parietal cells found within the body mucosa (Figures 3B and 4G). However, we also found that all three stomachs showed prominent numbers of parietal cells in groups of glands in the antral region. While the numbers of parietal cells in antral glands represented only 5% of the total number in the stomach, they were consistently present in the antrum extending towards the pyloric junction (Supplemental Figure 3). The distribution of MIST1-immunoreactive chief cells followed a pattern similar to that seen for parietal cells with 91% of cells found in the anatomic body (Figures 3C and 4H). However, we again observed chief cells in groups of glands throughout the anatomic antrum.

The identification of mucous neck cells is predicated on the use of antibodies against MUC6 or its companion trefoil protein, TFF2. However, MUC6 and TFF2 are also secreted from the deep antral gland mucous cells as well as from Brunner’s glands [22, 23]. Thus, as expected, we observed the presence of MUC6-expressing cells throughout the stomach (Figures 3D and 4I). In the fundic region, the MUC6-immunoreactive cells displayed a small, triangular cell morphology and were present in the mid-gland region, all characteristics of mucous neck cells (Figure 3D). However, in the antral region, cells with two different morphologies were observed. Some glands showed the morphology of mucous neck cells in the mid-gland regions, but others showed the foamy, open-ended morphology classically ascribed to deep antral gland mucous cells (Figure 3D). Thus, together, these data suggested that oxyntic type glands were present throughout the human antrum.

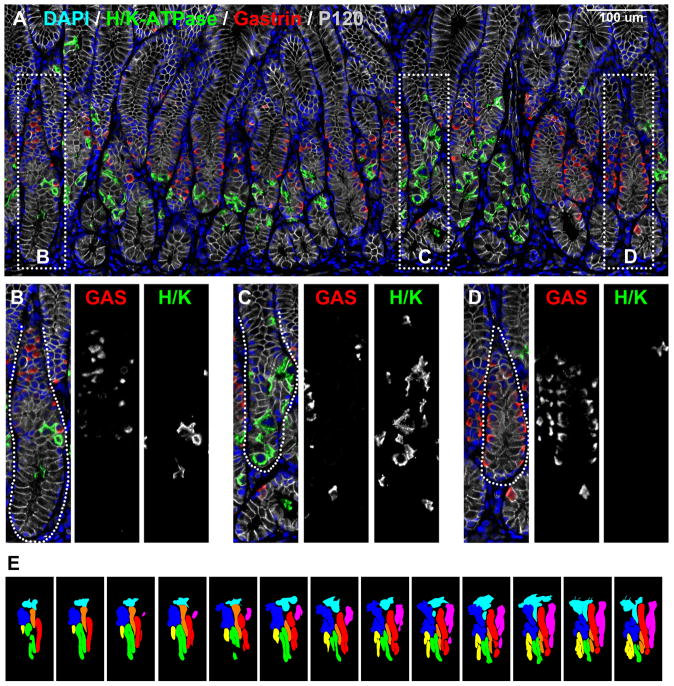

The human antral mucosa is assembled from a mixture of “oxyntic” and “gastrin” glands

To analyze in greater detail the structure of glands in the antrum, we performed dual staining for H/K-ATPase and gastrin on arrayed samples of the stomach and paraffin sections of human antrum from six other organ donor specimens. Figure 5 demonstrates that we observed a marked heterogeneity among gland types in the anatomical antrum with groups of glands containing gastrin cells (Figure 5D) interspersed with glands containing parietal cells (Figure 5C). Most of the antral cores where gastrin cells were present showed heterogeneity among the glands. In addition, 50% of glands showed a “mixed” phenotype containing both gastrin cells and parietal cells (Figure 5B). These mixed-type glands contained fewer parietal cells per gland compared to the oxyntic glands in the body and the parietal cells were generally located deep to the gastrin-expressing cells. Within these glands, we occasionally observed cells, which co-stained for both H/K-ATPase and gastrin (Supplemental Figure 5A). These findings suggest that the H/K-ATPase- and gastrin-expressing cells in the antrum might be derived from the same progenitor cell population.

Figure 5. Immunofluorescence staining for parietal cells in human antrum.

Paraffin sections of human gastric antrum were immunostained for H/K-ATPase (parietal cells, green) and gastrin (G cells, red). P120 (grey scale) immunostaining was used for lateral membrane staining and DAPI (blue) was used for nuclear staining. Dotted boxes in panel A indicate regions enlarged in B-D. Three populations of glands were observed in the human antrum: B) oxyntic glands with parietal cells but not gastrin cells, C) mixed glands with both parietal cells and gastrin cells and D) antral-type glands with gastrin cells. Scale bars are as indicated. E. Tracings of glands in 13 serial sections. Glands morphologies were defined as “gastrin” or “mixed” based on triple labeling with antibodies against gastrin (red), H/K-ATPase (green) and p120 (blue). The color-coding for traced gland units was as follows: Red, orange, and green –antral-type glands lacking parietal cells, pink and yellow – mixed-type glands with both parietal cells and gastrin cells, light blue and blue – incompletely mapped glands.

Characterization of antral gland sub-types

To examine the relationship of these three gland types in the distal human stomach, we stained 13 serial sections from human antrum for gastrin and H/K-ATPase along with p120 to outline the lateral membranes of cells (Figure 5E and Supplemental Figure 5B). The images of the stained serial sections were then used to assemble three-dimensional reconstructions of the gland structures (Supplemental Video 10). The reconstruction shows that the gland types, while separated in the deep portions, merged with each other in the upper foveolar regions (Supplemental Figure 5B). Furthermore, foveolar regions often displayed further ramifications. These results suggest that the deep antral glands form with multiple lineage configurations.

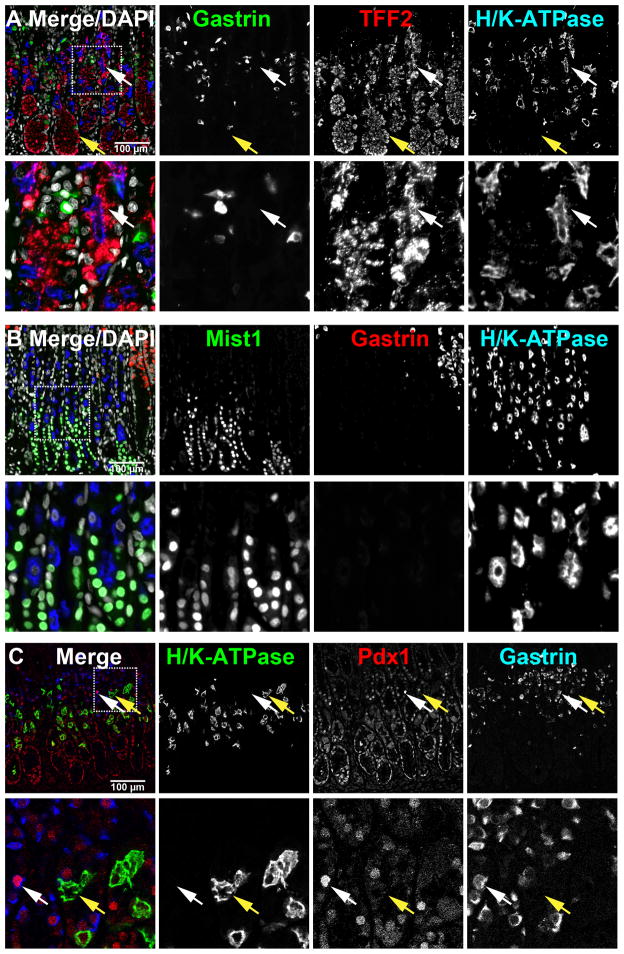

Since the oxyntic-type glands in the antrum clearly contained only a third the number of parietal cells observed in the oxyntic glands in the stomach body, we next sought to determine if these glands contained other lineages traditionally observed in oxyntic glands. We utilized the morphology of TFF2-expressing cells to assess the presence of mucous neck cells. Figure 6A demonstrates that parietal cell-containing glands also contained mucous neck cells. These cells were clearly distinguishable as small, triangular cells compared to the larger basal antral gland-type cells. We also stained for MIST1-expressing chief cells, which are derived from mucous neck cells. MIST1-expressing chief cells were also present in glands with parietal cells, but not in glands with gastrin cells (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Characterization of gastric glands in human antrum.

Paraffin sections of human gastric antrum were immunostained for TFF2 (A), Mist1 (B) or Pdx1 (C) with both gastrin and H/K-ATPase. DAPI was used for nuclear staining. In panel A, the mucous neck cells (white arrow) and the deep antral mucous cells (yellow arrow) were immunostained for TFF2. In panel B, gastrin-expressing G cells were co-localized with Pdx1 (white arrow), however, H/K-ATPase-expressing parietal cells were not co-labeled with Pdx1 (yellow arrow). Dotted boxes depict regions enlarged. Scale bars are as indicated.

The immunohistochemical studies had demonstrated that the antral glands were essentially devoid of ghrelin cells, indicating that there were differences in the antral oxyntic glands. Histamine-secreting ECL cells perform a central role in the stimulation of acid secretion by parietal cells [24]. A previous investigation had demonstrated that ECL cells are present throughout the human stomach [19]. We therefore sought to determine whether the antral glands with parietal cells also contained histamine-secreting ECL cells by staining for histadine decarboxylase (HDC). HDC-immunoreactive cells were observed throughout the antrum and dual-labeling studies showed that ECL cells were present in all three types of antral glands (Supplemental Figure 6).

Previous investigations in rodents have suggested that antral gland cells express the transcription factor PDX1, which is responsible for patterning in the distal foregut [10]. We therefore stained human antral samples for Pdx1 to determine whether the parietal cells in the antrum also express this antral marker (Figure 6C). PDX1-expressing cells were observed in glands with gastrin cells, but not in glands with only parietal cells. PDX1 co-labeled with gastrin cells in the “mixed” glands. However, PDX1 was not observed in the nuclei of H/K-ATPase-expressing parietal cells, suggesting that PDX1-expressing antral progenitor cells may not give rise to parietal cells in the mixed glands.

Putative gastric stem cells in the human antrum

To understand how the mixture of cell lineages is assembled in antral glands, we next examined the distribution of putative gastric stem cells. In a mouse study, SOX2-expressing stem cells in stomach were found in both the body and antrum and the SOX2-expressing stem cells gave rise to both oxyntic and antral gland lineages [25]. We observed SOX2-expressing cells in the antral specimens of the human stomachs. SOX2-expressing cells were widely distributed throughout all three types of glands (Supplemental Figure 7A). Some SOX2-expressing cells were located between parietal cells and gastrin cells and we observed 1.95% of cells were co-positive for both SOX2 and H/K-ATPase and 2.50% were co-positive for both SOX2 and gastrin (Supplemental Figure 7A, white arrows and Supplemental Figure 7C). We also stained for Ki67 to assess whether the SOX2-expressing cells were proliferative (Supplemental Figure 7B). We observed that the Ki67-positive progenitor cells were located adjacent to SOX2-expressing cells. However, SOX2-expressing cells did not co-label with Ki67. Thus, these data suggested that the SOX2-expressing cells may represent a candidate of putative quiescent stem cells in human antrum, which can give rise to both “oxyntic” and “antral” gland lineages.

DISCUSSION

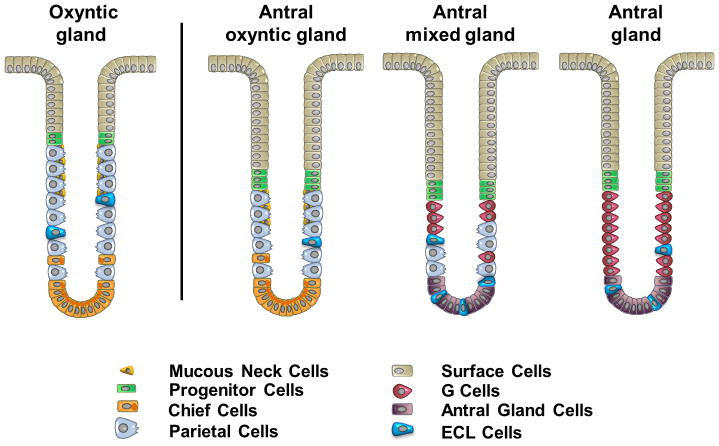

The present results have defined in detail for the first time the geographic anatomy of cell lineages within the human stomach. The findings here indicate that enteroendocrine cells are not, in general, uniformly distributed in the human stomach. Indeed ghrelin and gastrin are the best markers of the anatomic body and antrum, respectively. A concentration of somatostatin cells was observed in the proximal stomach. Previous studies have noted the enrichment of ghrelin cells in the human body of stomach [16]. Other studies have suggested that large numbers of enteroendocrine cells are present in the fetal human stomach before lineages such as parietal cells and chief cells that develop late in gestation [26]. Thus given the extensive projections that are present for most enteroendocrine cells [27], it is tempting to suggest that enteroendocrine cells may be a critical influence for the differentiation of gastric lineages during development as well as during adult life [28, 29]. Alternatively, concentrations and regionalization of enteroendocrine cells may coordinate local aspects of gastric physiology. In the present studies, the antrum in the H. pylori–negative organ donors contained a heterogeneous complement of glands (Figure 7) including those classically “antral” lineages (gastrin cells and deep antral mucous cells), those with oxyntic lineages (parietal cells and chief cells) and glands with mixed lineages (both parietal cells and gastrin cells). These observations contrast with studies in a number of animal species including rodents, rabbits, pigs, cats and dogs, where the fundic and antral regions segregate glandular mucosa containing the acid-secreting parietal cells from the gastrin cell-containing antrum [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 30]. Most textbook interpretations of gastric anatomy in humans have supported this notion, albeit with some acknowledgement that scattered parietal cells can be observed in the human antrum [31, 32, 33]. A number of studies have noted that a transitional zone exists between the body and antrum on both the lesser and greater curvatures in humans as well as in rodents.[6, 12, 34] This transitional zone contains glands with fewer parietal cells and may vary in length, especially along the greater curvature.[12] In our present studies, we also observed about a 90% decrease in parietal cell and chief cell numbers beginning in a region that corresponded to the border between the ghrelin-expressing body and the gastrin-expressing antrum (Figure 4). Still, in contrast to previous investigations that noted a transition zone at the border of the body and antrum, we observed parietal cell and chief cell-containing glands all of the way to the pylorus.

Figure 7. A new model of the heterogeneous types of human antral glands.

Analysis of the composition of gastric cells in human antrum indicates the existence of three types of glands: 1) the Antral oxyntic gland, 2) the Antral mixed gland and 3) the gastrin cell-containing Antral gland. The oxyntic gland represents the typical gland type present in the body of human stomach (shown at left) and contains more parietal cells than the antral oxyntic gland and a less prominent foveolar region.

Similar to our present findings, three previous investigations did note significant numbers of parietal cells in the human antrum: In his seminal paper in 1933, Berger noted the presence of parietal cells detected by Hematoxylin and eosin staining in the antral region [35]. Naik, et al. found that while gastrin cells clearly defined the anatomical border of the antrum, parietal cells were present in glands in the anatomical antrum [11]. Nevertheless, perhaps the most detailed study was published in 1975 by Tominaga [36], who reported parietal cells in the antral mucosa of 116 of 118 subjects. This work suggested that an absence of parietal cells in the human antrum was uncommon, and that the number of parietal cells in the antrum was not affected by gastritis. Another report has commented on the “unusual” existence of an acidic antrum, which was not amenable to acid reduction with highly selective vagotomy [37]. Our present findings support the results of these previous investigations and provide further evidence that the parietal cells in the human antral mucosa represent the presence of a variant of oxyntic glands. These antral oxyntic glands have 63% fewer parietal cells per gland, but also contain both chief cells and mucous neck cells (Figure 7). In addition, these glands appear to have a more prominent foveolar mucous cell component. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that these antral oxyntic glands, unlike their counterparts in the body, do not contain any ghrelin cells. Mixed glands have both parietal cells and gastrin cells, but do not contain chief cells.

Previous investigations in animal models have emphasized developmental regional borders within the gastrointestinal tract that define the boundaries of mucosal lineage derivation [10]. Thus, the antrum and glandular body in rodents contain gastrin or parietal cells, respectively. While transitional glands are present between the rodent body and antrum [6], they do separate homogeneous regions of oxyntic glands versus antral mucous glands. The derivation of the antrum in the mouse correlates with the domain in the distal foregut for the expression of the regulatory transcription factor PDX1 [10]. Glands in the antrum of rodents appear to be derived from Lgr5-expressing stem cells [38], whereas the glands of the fundic mucosa are not derived from such cell populations [39]. Our present findings suggest that the human antral mucosa is often made up of a mixture of oxyntic and antral type glands. We have also identified a population of glands with mixed lineages (Figure 7). In addition, occasional cells were observed expressing both H/K-ATPase and gastrin (Supplemental Figure 7). These findings indicate that a different paradigm must exist to explain the mixed gland phenotype in humans. The SOX2-expressing stem cells that are considered as marking quiescent stem cell populations are present in the mixed glands in human antrum. Thus, in humans, these SOX2-expressing stem cells may be able to give rise to both gastrin cells and parietal cells. Alternatively, mixed glands may contain two distinct sets of progenitor cells necessary for generating either parietal cells or gastrin cells. Nevertheless, in the context of the mixed glands, these progenitors appear to generate not only all of the gastrin gland lineages (surface cells, gastrin cells and deep antral mucous cells), but also parietal cells and ECL cells, without producing other normal oxyntic lineages (mucous neck cells and chief cells) (Figure 7). Nevertheless, the presence of other glands that are completely oxyntic or completely antral indicates that specialization is also possible. Wright and colleagues have previously noted that glands may replicate by fission to yield patches of glands derived from a single founder gland [40]. Since the range of plasticity is not clear, it is not possible to determine whether mixed glands represent the origin of these patches of oxyntic versus antral glands.

Taken together, these data suggest that there is considerable acid secretory capacity in the antrum from humans. Still, it remains unclear why, with the notable exception of the Tominaga paper [36], most recent authors have only commented on the presence of a smaller number of parietal cells in the transition zone between the body and the antrum. Tominaga noted no overall difference in the distribution of parietal cells in the antrum of patients with gastritis [36]. We have examined 3 complete stomachs and 6 antral specimens from organ donors, none of whom showed H. pylori infection. It is therefore possible that some of the differences may relate to the influence of H. pylori on antral gland lineages. However, since Tominaga’s observations were made in the 1970’s when H. pylori infection was extremely common in Japan, this possibility seems less likely. Thus, while the in-bred rodent strains used in most research may have more uniform patterns of gland geography, humans seem to possess a range of gland derivation patterns in the antrum. It is possible that these differences are related to genetic backgrounds, since examination of human fetal stomachs showed considerable heterogeneity in the distribution of parietal cells in the antrum [41]. In our own work, we have found no evidence for age-related effects on patterns of parietal cell distribution in the antrum. Thus, the human population seems to manifest considerable heterogeneity in the presence of mixed and oxyntic glands within the antrum.

In earlier studies in humans and rodents, we have demonstrated that Spasmolytic Polypeptide-expressing Metaplasia (SPEM) is associated with local focal changes stemming from parietal cell loss [42, 43]. These changes often involve only single glands [44], leading to the suggestion that SPEM reflects a normal reparative response to local damage of gastric glands. Indeed, we did observe instances of single SPEM glands lying within normal mucosa in the donor stomach samples (Supplemental Figure 8). In our previous investigations we have focused on metaplasia in the fundic region of the stomach, because it was difficult to identify morphologically the presence of SPEM in the antrum where the deep antral gland cells have similar morphology and express similar markers (MUC6 and TFF2) as SPEM cells. Nevertheless, our findings that the human antrum has a mixture of gland types, raises the question of the glandular origin of intestinal metaplasia in the human antrum. Previous investigations have noted that gastrin cells are completely absent in glands with intestinal metaplasia in the antrum [45]. Thus it is possible that intestinal metaplasia (as well as SPEM) might arise from oxyntic glands within the human antrum. This concept would provide a unified explanation for metaplastic processes in the stomach.

In summary, the present investigations demonstrate that a complete examination of the distribution of lineages within the human stomach has revealed complexity or heterogeneity in lineage distribution in the human antrum compared with lower mammalian species. The presence of three discrete types of glands within the human antrum suggests that the pattern of lineage derivation in the distal human stomach is more complicated than that detailed in rodent models. We have also documented regional concentrations of enteroendocrine cells within the stomach. Taken together, these findings indicate that geographic distributions of cell lineages and gland configurations within the human stomach may contribute to key aspects of gastric physiology and pathophysiology.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Two-dimensional maps of cell numbers from all three donors for endocrine lineages. Two-dimensional maps from all three donors with quantitation of A) Gastrin, B) Ghrelin and C) chromogranin A. The two-dimensional maps for donor 2 correspond to the 3-dimensional maps shown in Figure 2.

Supplemental Figure 2: Two-dimensional maps of cell numbers from all three donors for cell lineages. Two-dimensional maps from all three donors with quantitation of D) Serotonin, E) Somatostatin and F) Ki67. The two-dimensional maps for donor 2 correspond to the 3-dimensional maps shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Supplemental Figure 3: Two-dimensional maps of cell numbers from all three donors for cell lineages. Two-dimensional maps from all three donors with quantitation of G) H/K-ATPase (parietal cells), H) Mist1 (chief cells) and I) MUC6. The two-dimensional maps for donor 2 correspond to the 3-dimensional maps shown in Figure 3.

Supplemental Figure 4: Staining of representative cores from the body and antrum. A. Hematoxylin and eosin (left) and MUC5AC staining (right) for cores from the body of the stomach and the antrum. Note the greater foveolar height in the antrum. B. DLCK1 staining of a single tuft cell in an antral core. The inset demonstrates the tuft cell morphology with a prominent apical extension.

Supplemental Figure 5: A. Immunofluorescence staining for H/K-ATPase and Gastrin co-positive cells. Immunostaining for H/K-ATPase and gastrin from the stomach antrum demonstrates the presence of an H/K-ATPase and gastrin co-positive cell (yellow arrow). B. Assembly of gland tracing. Upper tracings of individual glands were outlined based on stained images in the lower panel for triple labeling with antibodies against gastrin (red), H/K-ATPase (green) and p120 (blue). The color-coding for traced gland units was as follows: Red, orange, and green – antral-type glands lacking parietal cells, pink and yellow – mixed-type glands with both parietal cells and gastrin cells, light blue and blue – incompletely mapped glands

Supplemental Figure 6. Immunofluorescence staining for ECL cells in the human antrum. Paraffin sections of human gastric antrum were immunostained for Histone decarboxylase (HDC), gastrin and H/K-ATPase. DAPI was used for nuclear staining. Dotted boxes depict regions enlarged. Scale bars are as indicated.

Supplemental Figure 7: Immunofluorescence staining for SOX2-expressing gastric stem cells in human antrum. Paraffin sections of human gastric antrum were immunostained for SOX2, gastrin and H/K-ATPase (A) and for SOX2 and Ki67 (B). DAPI was used for nuclear staining. Dotted boxes depict regions enlarged. White arrows indicate the position of cells co-labeled for both H/K-ATPase and SOX2. Scale bars are as indicated. C. Quantitation of SOX2-expressing cells co-positive for H/K-ATPase or Gastrin in human antrum. Sections were triple stained for SOX2, gastrin and H/K-ATPase. The graph represents the proportion of SOX2-expressing cells co-positive for SOX2 and gastrin (SOX2(+)GAS(+)) or co-positive for SOX2 and H/K-ATPase (SOX2(+)H/K(+)) or singly positive only for Sox2 (SOX2(+)) per 100 SOX2-expressing cells (n=3).

Supplemental Figure 8: Immunostaining for MUC6 in a core from the stomach body shows a single SPEM gland. Immunostaining for MUC6 in this core from the stomach body demonstrates the normal distribution of MUC6-staining mucous neck cells. The arrow indicates the presence of one gland with MUC6 staining of cells throughout a gland to its base, characteristic of SPEM.

Supplemental Video 1: 3-dimensional reconstruction of gastrin immunostaining cell distribution.

Supplemental Video 10: 3-dimensional reconstruction of antral gland phenotypes assembled from images in Figure 4E.

Supplemental Video 2: 3-dimensional reconstruction of ghrelin immunostaining cell distribution.

Supplemental Video 3: 3-dimensional reconstruction of chromogranin immunostaining cell distribution.

Supplemental Video 4: 3-dimensional reconstruction of serotonin immunostaining cell distribution.

Supplemental Video 5: 3-dimensional reconstruction of somatostatin immunostaining cell distribution.

Supplemental Video 6: 3-dimensional reconstruction of Ki67 immunostaining cell distribution.

Supplemental Video 7: 3-dimensional reconstruction of H/K-ATPase immunostaining cell distribution.

Supplemental Video 8: 3-dimensional reconstruction of Mist1 immunostaining cell distribution.

Supplemental Video 9: 3-dimensional reconstruction of MUC6 immunostaining cell distribution.

SUMMARY BOX.

What is known

Enteroendocrine cell lineages are distributed throughout the human stomach and regulate secretory physiology.

In the human stomach parietal cell-containing oxyntic glands are found in the body of the stomach.

In the human stomach gastrin cell-containing mucous glands are found in the antrum.

New findings

Enteroendocrine cells are regionally concentrated within the human stomach.

Human antrum contains three types of glands: oxyntic, antral and mixed.

The presence of both gastrin cells and parietal cells in mixed glands suggests that multiple stem cells may reside in human antral glands.

Impact on clinical practice

The presence of antral oxyntic and mixed glands may suggest that specific pathologies such as intestinal metaplasia in the antrum could arise from these glands.

Acknowledgments

Grant support and acknowledgments: This work is dedicated to the memory of Dr. John G. Forte, who inspired two generations of scientists to understand the physiology of gastric acid secretion. These studies were supported by a Transnational Pilot Grant Award from the Vanderbilt Digestive Disease Research Center (NIH P30 DK058404) and RO1 DK071590 to J.R.G. This work was supported by core resources of the Vanderbilt Digestive Disease Center (P30 DK058404), and the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center through NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA068485 utilizing the Transnational Pathology Shared Resource. These studies utilized Ariol SL-50 imaging in the VUMC Digital Histology Shared Resource. We thank Dr. Al Reynolds for antibodies against p120. We are grateful for the continuing assistance of the staff of Tennessee Donor Services whose efforts at organ procurement made this work possible.

Footnotes

The Corresponding Author, Dr. Goldenring, has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive license on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in Gut editions and any other BMJPGL products to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our license.

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest.

Author Roles:

Choi: Designed and performed studies, analyzed data, drafted manuscript.

Roland: Designed and performed studies, analyzed data, drafted manuscript.

Barlow: Performed studies.

O’Neal: Performed studies.

Rich: Performed studies.

Nam: Designed and performed studies, analyzed data.

Shi: Designed studies, analyzed data.

Goldenring: Designed studies, analyzed data, drafted manuscript.

References

- 1.Karam SM, Leblond CP. Dynamics of epithelial cells in the corpus of the mouse stomach. I. Identification of proliferative cell types and pinpointing of the stem cells. Anat Rec. 1993;236:259–79. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092360202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karam SM, Leblond CP. Dynamics of epithelial cells in the corpus of the mouse stomach. II. Outward migration of pit cells. Anat Rec. 1993;236:280–96. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092360203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karam SM, Leblond CP. Dynamics of epithelial cells in the corpus of the mouse stomach. III. Inward migration of neck cells followed by progressive transformation into zymogenic cells. Anat Rec. 1993;236:297–313. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092360204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karam SM. Dynamics of epithelial cells in the corpus of the mouse stomach. IV. Bidirectional migration of parietal cells ending in their gradual degeneration and loss. Anat Rec. 1993;236:314–32. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092360205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karam SM, Leblond CP. Dynamisc of epithelial cells in the corpus of the mouse stomach. V. Behavior of entero-endocrine and caveolated cells:general conclusions of cell kinetics in the oxyntic epithelium. Anat Rec. 1993;236:333–40. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092360206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee ER, Trasler J, Dwivedi S, Leblond CP. Division of the mouse gastric mucosa into zymogenic and mucous regions on the basis of gland features. Am J Anat. 1982;164:187–207. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001640302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowie DJ. The distribution of the chief or pepsin-forming cells in the gastric mucosa of the cat. Anat Record. 1940;78:9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Que J, Luo X, Schwartz RJ, Hogan BL. Multiple roles for Sox2 in the developing and adult mouse trachea. Development. 2009;136:1899–907. doi: 10.1242/dev.034629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wells JM, Melton DA. Vertebrate endoderm development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:393–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsson LI, Madsen OD, Serup P, Jonsson J, Edlund H. Pancreatic-duodenal homeobox 1 -role in gastric endocrine patterning. Mech Dev. 1996;60:175–84. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(96)00609-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naik KS, Lagopoulos M, Primrose JN. Distribution of antral G-cells in relation to the parietal cells of the stomach and anatomical boundaries. Clin Anat. 1990;3:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stave R, Brandtzaeg P, Nygaard K, Fausa O. The transitional body-antrum zone in resected human stomachs. Anatomical outline and parietal-cell and gastrin-cell characteristics in peptic ulcer disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1978;13:685–91. doi: 10.3109/00365527809181782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stave R, Elgjo K, Brandtzaeg P. Quantification of gastrin-producing cells (G cells) and parietal cells in relation to histopathological alterations in resected stomachs from patients with peptic ulcer disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1978;13:747–57. doi: 10.3109/00365527809181791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Royston CM, Polak J, Bloom SR, Cooke WM, Russell RC, Pearse AG, et al. G cell population of the gastric antrum, plasma gastrin, and gastric acid secretion in patients with and without duodenal ulcer. Gut. 1978;19:689–98. doi: 10.1136/gut.19.8.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nielsen HO, Teglbjaerg PS, Hage E. Gastrin and enteroglucagon cells in human antra, with special reference to intestinal metaplasia. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1979;54:101–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rindi G, Necchi V, Savio A, Torsello A, Zoli M, Locatelli V, et al. Characterisation of gastric ghrelin cells in man and other mammals: studies in adult and fetal tissues. Histochemistry and cell biology. 2002;117:511–9. doi: 10.1007/s00418-002-0415-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stengel A, Tache Y. Yin and Yang - the Gastric X/A-like Cell as Possible Dual Regulator of Food Intake. Journal of neurogastroenterology and motility. 2012;18:138–49. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2012.18.2.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rindi G, Buffa R, Sessa F, Tortora O, Solcia E. Chromogranin A, B and C immunoreactivities of mammalian endocrine cells. Distribution, distinction from costored hormones/prohormones and relationship with the argyrophil component of secretory granules. Histochemistry. 1986;85:19–28. doi: 10.1007/BF00508649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simonsson M, Eriksson S, Hakanson R, Lind T, Lonroth H, Lundell L, et al. Endocrine cells in the human oxyntic mucosa. A histochemical study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1988;23:1089–99. doi: 10.3109/00365528809090174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito H, Yokozaki H, Tokumo K, Nakajo S, Tahara E. Serotonin-containing EC cells in normal human gastric mucosa and in gastritis. Immunohistochemical, electron microscopic and autoradiographic studies. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1986;409:313–23. doi: 10.1007/BF00708249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kasacka I, Lebkowski W, Janiuk I, Lapinska J, Lewandowska A. Immunohistochemical identification and localisation of gastrin and somatostatin in endocrine cells of human pyloric gastric mucosa. Folia morphologica. 2012;71:39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanby AM, Poulsom R, Singh S, Elia G, Jeffery RE, Wright NA. Spasmolytic polypeptide is a major antral peptide: Distribution of the trefoil peptides human spasmolytic polypeptide and pS2 in the stomach. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1110–6. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90956-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elia G, Chinery R, Hanby AM, Poulsom R, Wright NA. The production and characterization of a new monoclonal antibody to the trefoil peptide human spasmolytic polypeptide. Histochem J. 1994;26:644–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00158289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hersey SJ, Sachs G. Gastric acid secretion. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:155–89. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnold K, Sarkar A, Yram MA, Polo JM, Bronson R, Sengupta S, et al. Sox2(+) adult stem and progenitor cells are important for tissue regeneration and survival of mice. Cell Stem Cell. 9:317–29. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitrovic O, Micic M, Radenkovic G, Vignjevic S, Dikic D, Budec M, et al. Endocrine cells in human fetal corpus of stomach: appearance, distribution, and density. J Gastroenterol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0597-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hauso O, Gustafsson BI, Waldum HL. Long slender cytoplasmic extensions: a common feature of neuroendocrine cells? Journal of neuroendocrinology. 2007;19:739–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2007.01578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aikou S, Fukushima Y, Ogawa M, Nozaki K, Saito T, Matsui T, et al. Alterations in gastric mucosal lineages before or after acute oxyntic atrophy in gastrin receptor and H2 histamine receptor-deficient mice. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1625–35. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0832-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nozaki K, Weis V, Wang TC, Falus A, Goldenring JR. Altered gastric chief cell lineage differentiation in histamine-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G1211–20. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90643.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyagawa Y. The Exact Distribution of the Gastric Glands in Man and in Certain Animals. Journal of anatomy. 1920;55:56–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Del Valle J, Todisco A. Textbook of Gastroenterology. 5. Oxford, U.K: Blackwell Publishing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boucher IAD, Allan RN, Hodgson HJF, Keighlem MRB. Testbook of Gastroenterology. London, UK: Bailliere Tindall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Surgical Pathology of the GI Tract, Liver, Biliary Tract, and Pancreas. 2. Saunders; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Zanten SJ, Dixon MF, Lee A. The gastric transitional zones: neglected links between gastroduodenal pathology and helicobacter ecology. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1217–29. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berger EH. The distribution of parietal cells in the stomach: A histopathological study. Amer J Anat. 1933;54:87–114. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tominaga K. Distribution of parietal cells in the antral mucosa of human stomachs. Gastroenterology. 1975;69:1201–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simms JM, Bird NC, Johnson AG. An unusual acid antrum. The British journal of surgery. 1985;72:12. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800720105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barker N, Huch M, Kujala P, van de Wetering M, Snippert HJ, van Es JH, et al. Lgr5(+ve) stem cells drive self-renewal in the stomach and build long-lived gastric units in vitro. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nam KT, O’Neal RL, Coffey RJ, Finke PE, Barker N, Goldenring JR. Spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia (SPEM) in the gastric oxyntic mucosa does not arise from Lgr5-expressing cells. Gut. 2011;61:1678–85. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McDonald SA, Greaves LC, Gutierrez-Gonzalez L, Rodriguez-Justo M, Deheragoda M, Leedham SJ, et al. Mechanisms of field cancerization in the human stomach: the expansion and spread of mutated gastric stem cells. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:500–10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelly EJ, Lagopoulos M, Primrose JN. Immunocytochemical localisation of parietal cells and G cells in the developing human stomach. Gut. 1993;34:1057–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.8.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmidt PH, Lee JR, Joshi V, Playford RJ, Poulsom R, Wright NA, et al. Identification of a metaplastic cell lineage associated with human gastric adenocarcinoma. Lab Invest. 1999;79:639–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nomura S, Yamaguchi H, Wang TC, Lee JR, Goldenring JR. Alterations in gastric mucosal lineages induced by acute oxyntic atrophy in wild type and gastrin deficient mice. Amer J Physiol. 2004;288:G362–G75. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00160.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halldorsdottir AM, Sigurdardottir M, Jonasson JG, Oddsdottir M, Magnusson J, Lee JR, et al. Spasmolytic polypeptide expressing metaplasia (SPEM) associated with gastric cancer in Iceland. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:431–41. doi: 10.1023/a:1022564027468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Otsuka T, Tsukamoto T, Mizoshita T, Inada K, Takenaka Y, Kato S, et al. Coexistence of gastric- and intestinal-type endocrine cells in gastric and intestinal mixed intestinal metaplasia of the human stomach. Pathology International. 2005;55:170–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2005.01809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Two-dimensional maps of cell numbers from all three donors for endocrine lineages. Two-dimensional maps from all three donors with quantitation of A) Gastrin, B) Ghrelin and C) chromogranin A. The two-dimensional maps for donor 2 correspond to the 3-dimensional maps shown in Figure 2.

Supplemental Figure 2: Two-dimensional maps of cell numbers from all three donors for cell lineages. Two-dimensional maps from all three donors with quantitation of D) Serotonin, E) Somatostatin and F) Ki67. The two-dimensional maps for donor 2 correspond to the 3-dimensional maps shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Supplemental Figure 3: Two-dimensional maps of cell numbers from all three donors for cell lineages. Two-dimensional maps from all three donors with quantitation of G) H/K-ATPase (parietal cells), H) Mist1 (chief cells) and I) MUC6. The two-dimensional maps for donor 2 correspond to the 3-dimensional maps shown in Figure 3.

Supplemental Figure 4: Staining of representative cores from the body and antrum. A. Hematoxylin and eosin (left) and MUC5AC staining (right) for cores from the body of the stomach and the antrum. Note the greater foveolar height in the antrum. B. DLCK1 staining of a single tuft cell in an antral core. The inset demonstrates the tuft cell morphology with a prominent apical extension.

Supplemental Figure 5: A. Immunofluorescence staining for H/K-ATPase and Gastrin co-positive cells. Immunostaining for H/K-ATPase and gastrin from the stomach antrum demonstrates the presence of an H/K-ATPase and gastrin co-positive cell (yellow arrow). B. Assembly of gland tracing. Upper tracings of individual glands were outlined based on stained images in the lower panel for triple labeling with antibodies against gastrin (red), H/K-ATPase (green) and p120 (blue). The color-coding for traced gland units was as follows: Red, orange, and green – antral-type glands lacking parietal cells, pink and yellow – mixed-type glands with both parietal cells and gastrin cells, light blue and blue – incompletely mapped glands

Supplemental Figure 6. Immunofluorescence staining for ECL cells in the human antrum. Paraffin sections of human gastric antrum were immunostained for Histone decarboxylase (HDC), gastrin and H/K-ATPase. DAPI was used for nuclear staining. Dotted boxes depict regions enlarged. Scale bars are as indicated.

Supplemental Figure 7: Immunofluorescence staining for SOX2-expressing gastric stem cells in human antrum. Paraffin sections of human gastric antrum were immunostained for SOX2, gastrin and H/K-ATPase (A) and for SOX2 and Ki67 (B). DAPI was used for nuclear staining. Dotted boxes depict regions enlarged. White arrows indicate the position of cells co-labeled for both H/K-ATPase and SOX2. Scale bars are as indicated. C. Quantitation of SOX2-expressing cells co-positive for H/K-ATPase or Gastrin in human antrum. Sections were triple stained for SOX2, gastrin and H/K-ATPase. The graph represents the proportion of SOX2-expressing cells co-positive for SOX2 and gastrin (SOX2(+)GAS(+)) or co-positive for SOX2 and H/K-ATPase (SOX2(+)H/K(+)) or singly positive only for Sox2 (SOX2(+)) per 100 SOX2-expressing cells (n=3).

Supplemental Figure 8: Immunostaining for MUC6 in a core from the stomach body shows a single SPEM gland. Immunostaining for MUC6 in this core from the stomach body demonstrates the normal distribution of MUC6-staining mucous neck cells. The arrow indicates the presence of one gland with MUC6 staining of cells throughout a gland to its base, characteristic of SPEM.

Supplemental Video 1: 3-dimensional reconstruction of gastrin immunostaining cell distribution.

Supplemental Video 10: 3-dimensional reconstruction of antral gland phenotypes assembled from images in Figure 4E.

Supplemental Video 2: 3-dimensional reconstruction of ghrelin immunostaining cell distribution.

Supplemental Video 3: 3-dimensional reconstruction of chromogranin immunostaining cell distribution.

Supplemental Video 4: 3-dimensional reconstruction of serotonin immunostaining cell distribution.

Supplemental Video 5: 3-dimensional reconstruction of somatostatin immunostaining cell distribution.

Supplemental Video 6: 3-dimensional reconstruction of Ki67 immunostaining cell distribution.

Supplemental Video 7: 3-dimensional reconstruction of H/K-ATPase immunostaining cell distribution.

Supplemental Video 8: 3-dimensional reconstruction of Mist1 immunostaining cell distribution.

Supplemental Video 9: 3-dimensional reconstruction of MUC6 immunostaining cell distribution.