Abstract

Background

The relationship between the duration of untreated psychosis and long-term clinical outcomes remains uncertain.

Objective

Prospectively assess the relationship of the duration of untreated psychosis on clinical outcomes in a sample of individuals with first-onset schizophrenia treated at the Pudong Mental Health Center from January 2007 to December 2008.

Methods

Information about general health, psychotic symptoms and social functioning were collected using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale (TESS), Morningside Rehabilitation Status Scale (MRSS), and Social Disability Screening Schedule (SDSS) at baseline and in June 2010 and June 2012.

Results

The 43 individuals with first-episode schizophrenia participating in the study were divided into short (<24 weeks) and long (>24weeks) duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) groups. The mean (sd) duration of follow-up was 1197 (401) days in the short DUP group and 1412 (306) days in the long DUP group (t=9.98, p=0.055). Despite less prominent psychotic symptoms at the time of first diagnosis among patients who had a long DUP compared to those with a short DUP (BPRS mean scores, 42.5 [8.4] v. 50.0 [10.6], t=2.42, p=0.0210) and a similar number of clinical relapses (based on positive symptoms assessed by the BPRS), patients with a long DUP were more likely to require hospitalization at the time of first diagnosis (52% [11/21] v. 9% [2/22], χ2=9.55, p=0.002) and more likely to require re-hospitalization during the first two years of treatment (67% [14/21] v. 32% [7/22], χ2=5.22, p=0.022). Moreover, after four years of routine treatment, despite a similar severity of positive symptoms, patients who had had a long DUP prior to initiating treatment had significantly poorer social functioning than those who had had a short DUP (SDSS mean scores, 7.0 [5.2] v. 3.4 [4.9], t=2.20, p=0.035).

Conclusions

These findings show that despite having a similar level of psychotic symptoms – as measured by the BPRS – compared to patients with a short DUP, patients with schizophrenia who have a long DUP prior to initial treatment have poorer long-term social functioning. This confirms the clinical importance of the early recognition and treatment of individuals with chronic psychotic conditions.

Keywords: schizophrenia, antipsychotics, treatment, follow-up studies, China

Abstract

背景

精神疾病未经治疗的时间和长期临床结局之间关系仍然存在争议。

目标

前瞻性评估浦东精神卫生中心2007年1月至2008年12月收治的首发精神分裂症患者未经治疗的时间与临床结果之间的关系。

方法

采用简明精神病评定量表(BPRS)、不良反应量表(TESS)、康复状态量表(MRSS)、以及社会功能缺陷筛选量表(SDSS)分别于基线、2010年6月和2012年6月收集一般健康状况,精神症状和社会功能相关信息。

结果

共43例首发精神分裂症患者参与研究,将其分为精神疾病未治疗(DUP)短期(<24周)和精神疾病未治疗(DUP)长期(>24周)两组。短期DUP组的平均随访时间为1197(SD=401)天,长期DUP组平均随访时间为1412(SD=306)天(t=9.98,p=0.055 )。尽管初诊时长期DUP组患者的精神病性症状较短期DUP组不明显( BPRS平均分, 42.5 [8.4] v. 50.0 [10.6],t=2.42,p=0.0210 ),并且两组临床复发次数类似(基于BPRS阳性症状量表评估),长期DUP组患者更可能在初诊时需要住院治疗(52% [11/21] v. 9% [2/22],χ2=9.55,p=0.002),并且在治疗的头两年更有可能再次住院(67% [14/21] v. 32% [7/22],χ2=5.22,p=0.022)。另外,经过四年的常规治疗后,虽然两组患者的阳性症状严重程度类似,但是治疗前具有较长DUP的患者比DUP较短的患者社会功能减退更明显。(SDSS平均,7.0 [5.2] v. 3.4 [4.9],t=2.20, p=0.035)。

结论

这些结果表明,与治疗前DUP较短的精神分裂症患者相比,尽管DUP较长的患者精神病性症状的严重程度类似(由BPRS测量),但长期社会功能较差。这证实了对慢性精神障碍患者早期识别和及时治疗的临床重要性。

1. Introduction

In individuals with schizophrenia, ‘duration of untreated psychosis’ (DUP) refers to the period between the onset of psychotic symptoms and the start of pharmacological treatment.[1] There are wide variations in DUP among patients seeking treatment for schizophrenia. Some studies report that individuals with a long DUP have worse clinical and social outcomes than those with short DUP.[2] For example, an Australian study among individuals with first-episode psychosis found that longer DUP was associated with worse outcomes even after controlling for potential confounding factors such as gender, age of onset, social functioning prior to onset, marital status, family income, race, and ethnicity.[3] Despite the difficulty of replicating this finding,[4] most researchers and clinicians believe that early detection and intervention in psychosis can lead to better long-term outcomes.[5] The current study assesses the relationship between DUP and long-term clinical outcomes in individuals with first-episode schizophrenia treated at the Pudong Mental Health Center in Shanghai, China.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

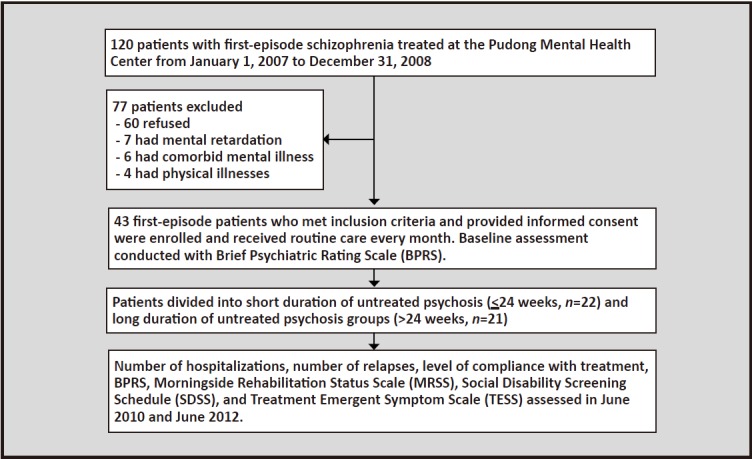

The enrollment of subjects is shown in Figure 1. Eligible individuals were persons living in Shanghai who sought treatment as inpatients or outpatients for first-onset schizophrenia at the Pudong Mental Health Center from January 1, 2007 to December 31, 2008. Patients who showed a good response to treatment after the first four weeks of treatment (i.e., a drop in total score of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale [BPRS][6] of 50% or greater) were asked to participate in a long-term follow-up study of treatment with antipsychotic medications. Included subjects were 16 to 50 years of age, met diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia according to the 3rd edition of the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders,[7] were in the first episode of illness, were drug-naïve or had not yet taken antipsychotic medications regularly prior to the first evaluation, had an IQ of greater than 70, did not have any serious physical illnesses, and did not have any co-morbid mental disorders (i.e., depression, alcohol dependence, etc.).

Figure 1. Flow chart of the study.

A total of 43 Shanghai residents (15 males and 28 females) provided written informed consent to participate in the study. They included 13 inpatients and 30 outpatients. Their mean (sd) age at the time of diagnosis was 36.7 (11.0) years and their mean age of onset was 33.2 (10.2) years. Duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) was defined as the time interval between the first occurrence of obvious abnormal behaviors (based on information provided by a co-resident family informant) and the beginning of systematic treatment with antipsychotic medications at our center. The DUP of the 43 patients ranged from 1 to 1458 weeks, the median DUP was 24 weeks, and the interquartile range (i.e., 25-75 percentile) was 4 to 216 weeks. The median DUP was used to dichotomize participants into short DUP and long DUP groups[3] (i.e., <24 weeks and >24 weeks). Using this method, 22 of the enrolled patients were in the short DUP group and 21 in the long DUP group.

2.2. Treatment and assessment

After initial stabilization (either as an inpatient or outpatient) all patients received routine outpatient treatment (primarily with antipsychotic medication) every month in our outpatient department. At each follow-up visit information was collected about compliance with antipsychotic treatment, psychotic symptoms, side effects, and so forth. During the maintenance phase of treatment the primary antipsychotic medications used in the 43 patients were risperidone (n=23), chlorpromazine (n=10), aripiprazole (n=4), olanzapine (n=3), and quetiapine (n=3). Thirteen (30%) of the 43 patients concurrently took more than one antipsychotic medication. During the maintenance period, the mean (sd) chlorpromazine-equivalent dosage[8]-[10] was 270 (159) mg/day.

Compliance was calculated as the percent of prescribed antipsychotic medication that was actually taken.[11] Relapse was defined as a score of five (out of seven) in at least one of the 5 core symptoms assessed by the Chinese version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)[6] (i.e., conceptual disorganization, suspiciousness, hallucinations, unusual thought content, and bizarre behavior) or a score of four in at least two of the five core symptoms at any point during follow-up.[12] During the follow-up period patients were temporarily hospitalized if the treating clinician considered it necessary to stabilize the patient’s condition.

Three separate evaluations for the purposes of this study were conducted at the time of initiating antipsychotic treatment (i.e., when first diagnosed), in June 2010, and in June 2012. A psychiatrist who had received specialized training in the use of assessment tools for the evaluation of psychotic patients conducted all of these assessments. The initial evaluation was limited to the BPRS; the evaluations in June 2010 and June 2012 included the BPRS, the Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale (TESS),[13] the Morningside Rehabilitation Status Scale (MRSS),[14] and the Social Disability Screening Schedule (SDSS).[15] All of these instruments have been shown to have satisfactory reliability and validity in Chinese samples.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Pudong Mental Health Center. All subjects signed informed consent.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

SPSS 11.0 statistical software was used for data management and analyses. T-tests and repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare clinical outcomes between the short DUP and long DUP groups. The percent reduction in BPRS scores in June 2010 and June 2012 were calculated by subtracting the last BPRS total score available at those times from the baseline total BRPS score and then dividing the result by the baseline BPRS score. Four patients in the short DUP group and two patients in the long DUP group did not complete the MRSS at both time points. Two patients in the short DUP group and one patient in the long DUP group did not complete the SDSS at both time points. Therefore, the analytical sample sizes are 43, 37, and 39 for BPRS, MRSS, and SDSS, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of the characteristics of the two groups of patients

There were fewer women in the short DUP group than in the long DUP group (50% v. 81%, χ2=4.53, p=0.033), but there were no significant differences between the two groups in any of the other demographic variables at the time of the initial diagnosis: mean (sd) age (34.2 [9.6] v. 39.3 [11.9], t=1.54, p=0.133), mean years of education (11.3 [2.2] v. 11.7 [4.2] years, t=0.34, p=0.732), proportion currently married (32% v. 38%, χ2=0.19, p=0.666), and proportion currently employed (52% v. 52%, χ2=0.02, p=0.887).

The mean age of onset in the short DUP and long DUP groups were similar (34.1 [9.6] v. 32.3 [11.0], t=0.57, p=0.575) and there was no significant difference in the proportion that had a family history of mental illness (45% v. 38%, χ2=0.24, p=0.625). Despite having somewhat more acute symptoms, patients in the short DUP group were less likely to be hospitalized than those in the long DUP at the time of the initial assessment (9% [2/21] v. 52% [11/21], χ2=9.55, p=0.002).

At the time of the June 2010 follow-up assessment the mean (sd) follow-up times of the 22 patients in the short DUP group and the 21 patients in the long DUP group were 830 (234) days and 864 (204) days, respectively (t=0.52, p=0.605). At the time of the June 2012 follow-up assessment the mean follow-up times of the short DUP and long DUP groups were 1197 (401) days and 1412 (306) days, respectively (t=9.98, p=0.055). There were no significant differences in the mean chlorpromazine-equivalent dosage of antipsychotic medication used during the maintenance phase of treatment in the two groups (225 [144] mg/day v. 317 [164] mg/day, t=1.954, p=0.057), in the proportion that regularly used more than one antipsychotic medication (27% v. 33%, χ2=0.19, p=0.665), or in the proportion that experienced clinically significant side effects at any point during the follow-up (82% v. 71%, χ2=0.65, p=0.419).

3.2. Relationships between DUP and BPRS, MRSS and SDSS scores

As shown in Table 1, the mean total BPRS scores were significantly higher in the short DUP group than in the long DUP group at the time of enrollment, but the scores converged and were no longer significantly different at the time of the June 2010 and June 2012 re-evaluations. The mean percent reduction in the BPRS score from baseline to the June 2010 follow-up evaluation was significantly greater in the short DUP group than in the long DUP group (52.7% [15.4%] v. 39.1% [21.5%], F=2.13, p=0.039) but by the time of the June 2012 follow-up the difference between the groups in the mean percent reduction from baseline was no longer statistically significant (50.1% [17.5%] in the short DUP group v. 42.7% [18.0%] in the long DUP group, F=1.38, p=0.175).

Table 1 also shows the results of the MRSS and SDSS evaluations. At the time of the first follow-up assessment in June 2010 the scores on these two scales were similar in the short DUP and long DUP groups, but four years after the initial diagnosis (i.e., the June 2012 assessment) the rehabilitation status and social disability was substantially worse in the long DUP group than in the short DUP group, though only the difference in the SDSS scores reached statistical significance.

Table 1.

Comparison of mean baseline BPRS scores and mean BPRS, MRSS and SDSS scores between individuals with schizophrenia with short (≤24 weeks) and long (>24 weeks) duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) an average of 2 years and 4 years after initiating treatment

| mean (sd) BPRS total scoresa | mean (sd) MRSS scoresb | mean (sd) SDSS scoresc | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| baseline | June 2010 follow-up | June 2012 follow-up | June 2010 follow-up | June 2012 follow-up | June 2010 follow-up | June 2012 follow-up | |||

| Short DUP group | [n=22] 50.0 (10.6) |

[n=22] 26.3 (11.5) |

[n=22] 24.9 (9.8) |

[n=18] 81.6 (58.4) |

[n=18] 38.4 (39.8) |

[n=20] 7.0 (4.8) |

[n=20] 3.4 (4.9) |

||

| Long DUP group | [n=22] 42.5 (8.4) |

[n=21] 23.8 (7.5) |

[n=21] 24.4 (8.7) |

[n=19] 77.7 (47.7) |

[n=19] 52.6 (33.2) |

[n=20] 8.4 (3.7) |

[n=20] 7.0 (5.2) |

||

| t | 2.42 | 0.79 | -0.17 | 0.23 | 1.19 | 1.01 | 2.20 | ||

| p | 0.021 | 0.433 | 0.869 | 0.823 | 0.240 | 0.321 | 0.035 | ||

BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; MRSS, Morning Side Rehabilitation Status Scale; SDSS, Social Disability Screening Schedule

a Repeated measure ANOVA showed that the overall between-group difference in BPRS was not statistically significant (F=0.572, p=0.454)

b Within group differences in the MRSS score from June 2010 to June 2012 was significantly different in both short DUP group (t=3.31,p=0.004) and the long DUP group (t=3.87, p=0.001).

c Within group differences in the SDSS score from June 2010 to June 2012 was significantly different in short DUP group (t=2.17, p=0.040) but not in the long DUP group (t=1.19, p=0.250).

3.3. Relationships between DUP and compliance, number of relapses, and number of hospitalizations

As shown in Table 2, by the time of the June 2010 and June 2012 follow-up assessments the level of treatment compliance (i.e., proportion of prescribed medications actually taken up until the time of the assessment) was substantially lower in the short DUP group than in the long DUP group, but these differences did not reach statistical significance at either of these times.

Table 2.

Comparison of treatment compliance, number of relapses, and number of hospitalizations between individuals with schizophrenia with short (≤ 24 weeks) and long (>24 weeks) duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) 2 years and 4 years after initiating treatment

| Treatment compliance (%) | Number of relapses | Number of re-hospitalizations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| June 2010 follow-up | June 2012 follow-up | June 2010 follow-up | June 2012 follow-up | June 2010 follow-up | June 2012 follow-up | |||

| Short DUP group (n=22) median (interquartile range) |

62.4 (36.7-100) |

58.3 (9.2-58.3) |

0 (0-0) |

0.5 (0-1.0) |

0 (0-1.0) |

1.0 (0-1.0) |

||

| Long DUP group (n=21) median (interquartile range) |

78.6 (33.6-100) |

88.4 (43.9-100) |

0 (0-1.0) |

1.0 (0-1.0) |

1.0 (0-1.0) |

1.0 (0.3-1.0) |

||

| Z | 0.30 | 0.99 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 2.56 | 2.17 | ||

| p | 0.765 | 0.323 | 0.549 | 0.660 | 0.010 | 0.030 | ||

At the time of the June 2010 follow-up, 11 of the 22 patients in the short DUP group had relapsed once and none had relapsed twice while 8 of the 21 patients in the long DUP group had relapsed once and 3 had relapsed twice. By the June 2012, 9 of the 22 patients in the short DUP group had relapsed once and 2 had relapsed twice while 7 of the 21 patients in the long DUP group had relapsed once and 4 had relapsed twice. Thus at both time periods 50% (11/21) of patients in the short DUP group and 52% (11/21) of those in the long DUP group had relapsed (χ2=0.02, p=0.876). The results for the total number of relapses in each group are shown in Table 2.

At the time of the June 2010 follow-up, 7 of the 22 patients in the short DUP group had been re-hospitalized once and none had been re-hospitalized twice while 10 of the 21 patients in the long DUP group had been re-hospitalized once and 4 had been re-hospitalized twice. (These numbers do not include the initial hospitalizations, if any, at the time of enrollment in the follow-up study.) There were no further hospitalizations in either group from June 2010 to June 2012. Thus, at both follow-up times 32% (7/22) of patients in the short DUP group had been re-hospitalized while 67% (14/21) of the patients in the long DUP group had been re-hospitalized (χ2=5.22, p=0.022). The results for the total number of re-hospitalizations are shown in Table 2.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings

This study conducted a 4-year follow-up of first-episode patients with schizophrenia receiving standard treatment with antipsychotic medication. We found that despite similar or less prominent levels of positive symptoms of psychosis and a similar number of relapses as assessed by changes in the scores of the BPRS (i.e., positive symptoms), compared to patients with a short DUP (<24 weeks) patients with a long DUP (>24 weeks) were more likely to require hospitalization at the time of initial diagnosis, more likely to be re-hospitalized during the first two years of treatment, and more likely to have moderate to severe social dysfunction after four years of treatment.

The less prominent positive symptoms at the time of diagnosis of patients with long DUP than those with short DUP is consistent with the findings of a retrospective study by Altamura and colleagues[16] who suggest that the less florid symptoms is a major factor in the delay in receiving psychiatric care. Altamura also suggests that the higher number of females with a long DUP – which we also found – occurs because the higher levels of estrogen in female patients may suppress the more florid psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia.

We also found a much more rapid fall in the severity of psychotic symptoms during the first two years of treatment in the short DUP group than in the long DUP group. This is partly explained by the higher BPRS scores of the short DUP group at entry into the study but it suggests that patients with a long DUP recover more slowly than those with a short DUP. Findings from previous research on the relationship of DUP and the rate of recovery have been inconsistent,[5] but most studies[17] report that patients with longer DUP take longer to recover from their first episode of illness.

Most previous studies find that a longer DUP is associated with more relapses.[5],[16],[17] The current study found no differences in the number of relapses – as defined by changes in the positive psychotic symptoms assessed by the BPRS – but we did find a two-fold increase in the number hospitalizations in the long DUP group over the first two years of treatment. There was also a substantially higher, though not statistically significant, level of compliance in the long DUP group than in the short DUP group. It’s possible that the higher level of compliance in the long DUP group suppressed the predilection of these patients to have a higher rate of clinical relapses. It’s also possible that the slower rate of recovery or the higher level of social dysfunction in the long DUP necessitated re-hospitalization despite the lack of florid psychotic symptoms. One other possibility is that this sample, which has a much later age of onset (32 in the short DUP group and 34 in the long DUP) than is usually reported for schizophrenia (which occurred because our hospital tends to treat currently employed patients, not students) has a different developmental course of their illness than younger patients. Given the small sample in our study it was not possible to conduct subgroup analyses that would help clarify these issues.

We also found that after four years of treatment the long DUP group had substantial decrements in social functioning compared to the short DUP group, both as assessed by the MRSS (a substantial, but statistically non-significant difference) and the SDSS (a statistically significant difference). Thus our findings do not concur with those of Shrivastava and colleagues[19] who reported no differences in clinical and social outcomes between patients with short and long DUP after a 10-year follow-up. This difference between these studies may be due to the shorter follow-up in our study, different definitions of DUP (we used a relatively long 24 month cutoff time) or the older age of first-onset of the patients in our sample.

4.2. Limitations

Several issues need to be considered when interpreting these results. (a) The sample size was too small to adjust the results for the confounders that may have affected the outcome, specifically, the significant imbalance in gender, the proportion of participants who were hospitalized at the time of enrollment, the different levels of medication compliance, and the substantial (though non-significant) difference in the time of follow-up of the two groups. (b) The mean age of onset of our subjects is quite late (33 years of age) (which occurs because younger patients living with parents often receive treatment in another hospital in Shanghai) so the results may not be representative of all patients with first-onset schizophrenia. (c) Enrollment continued over a period of two years but follow-up assessments were conducted at specific dates, so patients were followed-up at very different time intervals after enrollment, not at 2-years and 4-years after enrollment as initially intended. (d) The use of a single unblinded evaluator to assess all the outcomes may have introduced some bias in the results. (e) The two main social measures employed in the study, MRSS and SDSS, are dependent on reports of co-resident family members of the patient; these reports could be biased or, if the respondent has relatively little contact with the patient, incorrect. (f) Like in all similar studies, estimation of DUP, the main variable of interest, is based on the often imperfect recall of the patient and his or her family informants. (g) To simplify the analysis we dichotomized the DUP, but this reduces the power of the analysis so it may be better to divide the DUP, which is heavily skewed, into a 3- to 5-level ranked variable.

4.3. Implications

Despite convergence in the severity of the positive symptoms of schizophrenia over time between patients who had a long DUP or a short DUP, after four years of follow-up those with long DUP had more prominent social dysfunction and were twice as likely to have been re-hospitalized during the follow-up period than patients with short DUP. Thus, compared to patients with schizophrenia who have a short DUP, those with a long DUP tend to have less prominent psychotic symptoms at the time of initial presentation but their symptoms resolve more slowly and they are more likely to have more residual social disability. The small sample size in the study made it impossible to make important statistical adjustments to these findings and to do any subgroup analyses, but the basic finding supports the findings of previous studies that report poorer long-term outcomes for patients with schizophrenia who have a long DUP prior to initial treatment with antipsychotic medications. This confirms the clinical importance of the early recognition and treatment of individuals with chronic psychotic conditions.

Biography

Dr. Hongyun Qin graduated from the Fudan University Medical School and has been working as a psychiatrist at the Pudong Mental Health Center since July 2004. She is currently an attending psychiatrist and is pursuing a master’s degree. Her research interest is the individualized intervention of early onset schizophrenia in community settings.

Funding Statement

The current study was supported by the Shanghai Pudong District Health Bureau Science and Technology Program (PW2008A-19).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Authors declare no conflict of interest related to this article.

References

- 1.Qin HY. [The main methods and effects of early intervention in schizophrenia] Zhongguo Min Kang Yi Xue. 2008;20(17):2029–2030. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-0369.2008.17.044. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oliveira AM, Menezes PR, Busatto GF, McGuire PK, Murray RM, Scazufca M. Family context and duration of untreated psychosis (DUP): results from the Sao Paulo Study. Schizophr Res. 2010;119(1-3):124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Primavera D, Bandecchi C, Lepori T, Sanna1 L, Nicotra E, Carpiniello B. Does duration of untreated psychosis predict very long term outcome of schizophrenic disorders? Results of a retrospective study. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2012;11:21. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-11-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schimmelmann BG, Huber CG, Lambert M, Cotton S, McGorry PD, Conus P. Impact of duration of untreated psychosis on pre-treatment, baseline, and outcome characteristics in an epidemiological first-episode psychosis cohort. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42(12):982–990. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang JJ, Zhang MD. [Duration of untreated psychosis in schizophrenia] Shanghai Jing Shen Yi Xue. 2005;17(6):356–359. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang ZJ, editor. [Scales and Questionnaires in Behavioral Medicine] Beijing: Chinese Medical Audio-Video Organization; 2005. pp. 332–334. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Society of Psychiatry, Chinese Medical Association. [Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition (CCMD-3)] Shandong Province: Shangdong Science and Technology Publishing House; 2001. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrease NC, Pressler M, Nopoulos P, Miller D, Ho BC. Antipsychotic dose equivalents and dose-years: a standardized method for comparing exposure to different drugs. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis JM, Chen N. Dose response and doses equivalence of antipsychotics. Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(2):192–208. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000117422.05703.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woods SW. Chlorpromazine equivalent does for the newer atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:663–667. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward A, Ishak K, Proskorovsky I, Caro J. Compliance with refilling prescriptions for atypical antipsychotic agents and its association with the risks for hospitalization, suicide, and death in patients with schizophrenia in Quebec and Saskatchewan: A Retrospective Database Study. Clinical Therapeutics. 2006;28:1912–1921. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niu YJ, Wu CJ, Phillips M, Ji ZF. [Factors related to the relapse of first-episode schizophrenia] 2006, 20(3): 19 -197 doi: 10.3321/j.issn:1000-6729.2006.03.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guy W, editor. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology (Revised) 1976. Dosage Record and Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale; pp. 223–244. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu QF, Zhu ZQ, Meng GR, Huang BK, Wang GB. [Reliability and validity of Morningside Rehabilitation Stats Scale] Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 1998;10(3):147–149. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang MY, editor. [Scales and Questionnaires in Psychiatry, 2nd ed] Hunan: Hunan Science and Technology Press; 2003. pp. 163–166. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altamura AC, Bassetti R, Sassella F, Salvadori D, Mundo E. Duration of untreated psychosis as a predictor of outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a retrospective study. Schizophr Res. 2001;52(1-2):29–36. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(00)00187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris MG, Henry LP, Harrigan SM, Purcell R, Schwartz OS, Farrelly SE, et al. The relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome: An eight-year prospective study. Schizophr Res. 2005;79(1):85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ucok A, Cakır S, Genc A. One-year outcome in first episode schizophrenia predictors of relapse. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci . 2006;256:37–43. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0598-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shrivastava A, Shah N, Johnston M, Stitt L, Thakar M, Chinnasamy G. Effects of duration of untreated psychosis on long-term outcome of people hospitalized with first episode schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:164–167. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.64583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]