Abstract

Background

A community-based rehabilitation program is an essential element of the comprehensive treatment of individuals with schizophrenia.

Objective

Assess the long-term effects of a community-based case management program for providing rehabilitations services to individuals with schizophrenia.

Methods

A total of 730 community-residing participants who met ICD-10 diagnostic criteriafor schizophrenia were enrolled, 380 in the case management group and 350 in the control group from two districts in Shanghai. Case management involved monthly training visits with patients and their co-resident family members that focused on encouraging medication adherence. Participants were assessed every three months for 24 months with the Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN), Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), WHO-Disability Assessment Scale (WHO-DAS), and the Quality of Life Scale (QOLS). Level of discomfort due to side-effects was also assessed every three months. Individuals who discontinued their antipsychotic medication without physician approval for one month or longer at any time during follow-up were classified as ‘self-determined medication discontinuation’.

Results

Compared to the treatment as usual group (i.e., follow-up management every 3 months), by the end of the two-year follow-up those who participated in the case management program had significantly lower rates of medication discontinuation, significantly less severe negative symptoms, lower relapse rates and lower rehospitalization rates. Other factors that had an independent effect on discontinuation of medication included educational level (those with more education had higher discontinuation rates), lack of family supervision of medication, higher dosages of medication, and greater medication-related discomfort.

Conclusions

Case management is a feasible and effective long-term method for improving the rehabilitation outcomes of community residents with schizophrenia. Our results highlight the need to involve family members in the management of patients’ medication, to use the minimum effective dosage of medication, and to aggressively manage all side-effects.

Keywords: schizophrenia, community-based rehabilitation, case management, discontinuation rate, social function

Abstract

背景

以社区为基础的康复方案是精神分裂症患者综合治疗的基本要素。

目的

评估以社区为基础的个案管理为精神分裂症患者提供康复服务的长期效果。

方法

从上海两区共招募730名符合ICD-10精神分裂症诊断标准的社区居民,380名纳入个案管理组和350名纳入对照组。个案管理涉及每月培训拜访患者和他们的家庭成员,侧重于鼓励患者坚持服药。在24个月中参加者每3个月使用Camberwell需求评价量表(CAN),阳性和阴性症状量表(PANSS),世界卫生组织残疾评定量表(WHO-DAS)和生活质量表(QOLS)进行一次评估。那些没有得到医生批准而停止服用抗精神病药物一个月或更长的患者被归为 “自行决定停药”。

结果

相比于常规治疗组(即每3个月的随访管理),参加个案管理计划的患者两年随访后停止服药率显著降低,阴性症状的严重程度显著降低,复发率降低并且再住院率也降低了。对停止服药有独立影响的其他因素包括文化程度(受教育程度越高,停药率越高),用药缺乏家庭监督,用药剂量较高,以及与药物相关的不良反应。

结论

个案管理是一种可行而且有效的长期方法,可以改善社区精神分裂症患者的康复效果。我们的研究结果强调家人需要参与患者的用药管理,使用药物的最小有效剂量,并积极处理所有的副作用。

1. Introduction

As part of the three-tier mental health service delivery system established in China in the late 1970s, in the early 1980s the Shanghai Municipality set up a service network at the municipal, district (19 districts) and sub-district (220 sub-districts) levels that came to be known as the ‘Shanghai Model’ of psychiatric rehabilitation.[1] The municipal-level (tertiary) services were coordinated by the Shanghai Mental Health Center, the district-level (secondary) services were provided by district psychiatric hospitals, and the sub-district level (primary) community-based services were provided by community mental rehabilitation centers. Most of the hospitals were run by the Bureau of Health but some were run by the Bureau of Civil Affairs and the Bureau of Public Security; the rehabilitation centers were primarily administered by local authorities (e.g., the neighborhood committee). By the mid-1990s a number of serious problems had surfaced within this service delivery network because of a rapidly increasing patient load and because the community rehabilitation centers were not financially viable.[2] To address these problems over the last 20 years the number of beds at the district level hospitals has more than doubled (currently more than 8000 beds); the community rehabilitation centers have been replaced by community ‘Sunshine Centers’ centrally managed and financed by the Disabled Persons Federation; and the Shanghai Center for Disease Control (CDC) has developed a three-tier monitoring system of persons with serious mental disorders at the city, district and sub-district levels – the ‘Shanghai Management System for Patients with Serious Mental Disorders’ – that coordinates 3-monthly follow-up visits (by public health staff) and the provision of free medication to the 11,376 individuals with schizophrenia currently (as of the end of 2013) registered in the system.

Despite this expansion of services, serious problems remain: (a) only 17% of the Sunshine Centers and the district and sub-district CDC mental illness management groups have any staff members trained in rehabilitation; (b) the Sunshine Centers, the CDC monitoring system and the psychiatric hospitals are run by different government departments and institutions; and (c) the CDC center at the tertiary psychiatric hospital responsible for coordinating follow-up and services to all seriously mentally ill individuals in the city does not have the manpower to provide technical support and supervision to CDC centers situated in the 19 district-level psychiatric hospitals or to the CDC working groups in the 220 sub-districts that provide the direct community-level supervision of the patients. As a result of these problems, by the end of 2013 only 20% (2285/11,376) of the patients with schizophrenia registered in Shanghai’s CDC management system received community-based rehabilitation services at the Sunshine Centers.

Clearly some changes are needed to resurrect the ‘Shanghai Model’.[3] Based on the experiences of other countries that use a variety of case management models to provide community-based services for individuals with severe mental illnesses,[4]-[6] we developed a case management protocol suitable for community-dwelling individuals with schizophrenia in Shanghai and assessed its effectiveness over a two-year follow-up period.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

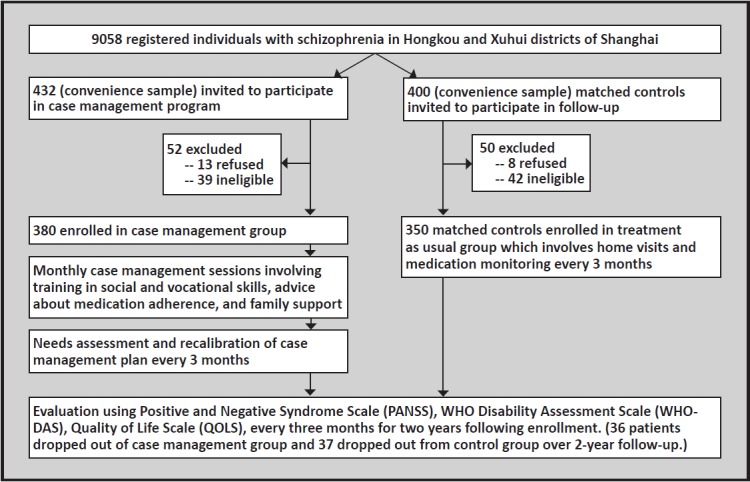

As shown in Figure 1, Individuals with schizophrenia were recruited from the Xuhui and Hongkou Districts of Shanghai. There are eight sub-districts in Hongkou District with 5231 individuals with schizophrenia registered in the CDC management system. There are 13 sub-districts in Xuhui District with 3827 registered individuals with schizophrenia. Patients with schizophrenia registered in the CDC system in these two districts have all received monthly follow-up visits and free medication for the last five years. The inclusion criteria for the current study were as follows: (a) ≥18 years of age; (b) met ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia; (c) had impairment in daily functioning due to the mental illness; and (d) the participants’ family members or guardians provided written informed consent.

Figure 1. Flow chart of the study.

A convenience sample of 380 subjects who met the inclusion criteria was recruited for the case management intervention group (study group) by the administrators of the district-level CDC monitoring system (who knew the patients well because they regularly follow-up patients each month). Controls matched for age (±5 years), gender, and duration of illness (±5 years) were identified from the same sub-districts for the first 350 subject in the study group. Due to time constraints we were unable to identify controls for the last 30 subjects recruited for the study group.

2.2. Case management

The implementation of case management followed six steps. (1) Eight case management teams (four case management teams for each district) were established. Each team had three or four members including at least one community psychiatrist, one nurse and one community health worker. Each team was responsible for managing 30 to 50 cases. (2) Baseline evaluations were conducted by each team to assess the health condition, recovery status, daily functioning, employment status, and social activities of participants in both the study group and the control group. (3) The needs of the participants were assessed using the Camberwell Assessment of Need[7](CAN). And (4) using information from the needs assessment, patient-specific case management plans were developed for all participants in the study group based on the content of the ‘Handbook of Rehabilitation for Individuals with Schizophrenia’,[8] which includes information on drug adherence training, daily skills training, family psychological intervention and so forth. (5) Throughout the two-year follow-up period the case management team visited each participant in the study group monthly (for about 30 minutes) to implement the training specified in the patient-specific management plan. (6) Patients in the study group also participated in eight group training sessions that covered the same material at the local Sunshine Center during the first year of enrollment.

Participants in the control group received regular monitoring follow-up every three months by the staff members of the district and sub-district monitoring system.

2.3. Evaluation

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale[9] (PANSS) was used to assess symptom severity; it contains a positive subscale, a negative subscale, and a general psychopathology subscale. The WHO Disability Assessment Scale[10] (WHO-DAS) was used to assess social functioning; it has 12 items that assess family functioning, employment functioning and social functioning. The Quality of Life Scale[11] (QOLS) includes 40 items divided into six domains: daily life, family life, social relationship, financial status, working status, and sense of security (higher scores represent a higher quality of life). Assessments were conducted at the baseline, and at 3, 6, 9, 12 and 24 months after recruitment. Team members were trained before the study and their inter-rater reliability for the various scales was good (Kappa=0.82-0.93). The study was conducted from August 1, 2008 to December 31, 2011. At each of these follow-up assessments clinicians also assess the degree of discomfort the individual experienced in the prior month due to side effects of the medication (rated ‘none’, ‘mild’, ‘obvious’ and ‘serious’ discomfort).

The main outcomes used to assess the efficacy of the case management method of supervising community-dwelling individuals with schizophrenia were medication adherence, relapse, and re-hospitalization. Medication discontinuation was defined as self-discontinuation of antipsychotic medication for one month or longer at any time during the 2-year follow-up (discontinuation by the treating clinician due to side effects was not counted). Relapse was defined as (a) an increase of at least 25% in PANSS total score, (b) an episode of self-harm, or (c) severe suicidal ideation that persists for at least one week.

2.4. Statistical analysis

SAS 9.0 statistical software was used for analysis. Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare between-group and within-group differences. Chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables. A backward stepwise logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with medication adherence; the factors entered into the model included group membership, gender (male=0, female =1), age, three levels of education (middle school or less, high school, and college or higher), duration of illness, supervision of medication by family members (yes or no), type of antipsychotic medication (traditional [including clozapine] or new atypical), mean dosage over the follow-up period (chlorpromazine-equivalent), and mean rating over the follow-up period of the 4-category discomfort due to side-effects variable. We used the intention-to-treat method with the Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) to address missing data. The level for statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

The study was approved by the Shanghai Mental Health Center.

3. Results

As shown in Table 1, there were no statistically significant differences between the study group in any of the baseline demographic and treatment variables. All patients were on stable dosages of a single antipsychotic medication that were provided free of charge. Most of the patients were taking oral perphenazine, chlorpromazine, clozapine, risperidone, or olanzapine. Throughout the 24-month follow-up only nine patients had to change their medication and the method of managing medication (either by family members or by the patient himself or herself) did not change.

Table 1.

Social and demographical characteristics of the participants

| Characteristic | Case management (n=380) |

Control (n=350) |

statistics | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (sd) age | 39.5(7.9) | 40.7 (9.3) | t=0.56 | 0.683 |

| Mean (sd) duration of illness in years | 11.6 (6.1) | 10.4 (7.6) | t=1.15 | 0.312 |

| Gender [n (%)] | ||||

| Male | 279 (73.4) | 243 (69.4) | χ2=1.43 | 0.233 |

| Female | 101 (26.6) | 107 (30.6) | ||

| Education level [n (%)] | ||||

| Middle school or lower | 138 (36.3) | 135 (38.6) | χ2=0.68 | 0.713 |

| High school | 191 (50.3) | 174 (49.7) | ||

| Junior college or above | 51 (13.4) | 41 (11.7) | ||

| Marital status [n (%)] | ||||

| Not married | 226 (59.6) | 235 (67.1) | ||

| Married | 129 (34.0) | 90 (25.6) | χ2=5.90 | 0.052 |

| Separated | 25 (6.4) | 25 (7.3) | ||

| Employment [n (%)] | ||||

| Unemployment | 53 (13.9) | 50 (14.3) | χ2=0.32 | 0.957 |

| Employed | 50 (13.2) | 45 (12.9) | ||

| Medical leave | 180 (47.4) | 160 (45.7) | ||

| Retired | 97 (25.5) | 95 (27.1) | ||

| Main caregiver [n (%)] | ||||

| Parents | 63 (16.6) | 61 (17.4) | ||

| Spouse | 120 (31.6) | 88 (25.1) | χ2=3.77 | 0.152 |

| Children or other relatives | 197 (51.8) | 201 (57.5) | ||

| Number of previous hospitalizations [mean (sd)] | 1.8 (1.7) | 1.8 (2.0) | t=0.03 | 0.956 |

| Family member supervises medication [n (%)] | 276 (72.6) | 245 (70.0) | χ2=0.62 | 0.432 |

| Uses new atypical antipsychotic [n (%)] | 142 (37.4) | 139 (39.7) | χ2=0.42 | 0.515 |

| Mean chlorpromazine equivalent dose over 2-year follow-up (mg/d) [mean(sd)] | 216.2 (146.8) | 237.5 (135.3) | t=1.18 | 0.129 |

| Uses relatively high mean dose of antipsychotic over 2-year follow-up (Chlorpromazine equivalent dose>400mg/day) [n (%)] | 62 (16.4) | 53 (15.1) | χ2=0.22 | 0.642 |

| Tolerance of medication over 2-year follow-up [n (%)] | ||||

| No discomfort | 67 (19.5) | 51 (14.6) | χ2=4.27 | 0.234 |

| Mild discomfort | 188 (48.3) | 172 (49.1) | ||

| Obvious discomfort | 82 (21.1) | 77 (22.0) | ||

| Serious discomfort | 43 (11.1) | 50 (14.3) |

3.1. Comparison of illness characteristics between treatment and control groups

The proportions of individuals who dropped out of the study, discontinued their medication, relapsed, and were rehospitalized over the 24-month follow-up period are shown in Table 2. There were no differences in the dropout rates between the two groups but after one year of case management the rates of discontinuing medication, relapse and rehospitalization were significantly greater in the control group than in the case management group.

Table 2.

Comparison of rates of loss to follow up, medication discontinuation, relapse, and rehospitalization between the case management group and the control group at five follow-up points (n, %)

| Time of follow-up | Case management (N=380) |

Control (n=350) |

χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months | ||||

| Lost to follow up | 0(0) | 0(0) | -- | -- |

| Discontinuation of medicine | 7 (1.9) | 10 (2.9) | 0.82 | 0.367 |

| Relapse | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.6) | Fisher's exact test | 1.000 |

| Rehospitalization | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.9) | Fisher's exact test | 0.675 |

| 6 months | ||||

| Lost to follow up | 4 (1.1) | 5 (1.4) | Fisher's exact test | 0.744 |

| Discontinuation of medicine | 14 (3.7) | 14 (4.1) | 0.05 | 0.824 |

| Relapse | 4 (1.1) | 7 (2.0) | Fisher's exact test | 0.368 |

| Rehospitalization | 6 (1.6) | 11 (3.1) | 1.96 | 0.162 |

| 9 months | ||||

| Lost to follow up | 10 (2.6) | 11 (3.1) | 0.17 | 0.680 |

| Discontinuation of medicine | 37 (9.7) | 43 (12.3) | 1.21 | 0.271 |

| Relapse | 19 (5.0) | 25 (7.1) | 1.47 | 0.224 |

| Rehospitalization | 17 (4.8) | 22 (6.3) | 1.18 | 0.279 |

| 12 months | ||||

| Lost to follow up | 17 (4.8) | 16 (4.6) | 0.02 | 0.878 |

| Discontinuation of medicine | 43 (11.3) | 58 (16.6) | 4.22 | 0.039 |

| Relapse | 30 (7.9) | 45 (12.9) | 4.87 | 0.027 |

| Rehospitalization | 25 (6.6) | 39 (11.1) | 4.74 | 0.029 |

| 24 months | ||||

| Lost to follow up | 36 (9.5) | 37 (10.6) | 0.24 | 0.621 |

| Discontinuation of medicine | 50 (13.2) | 80 (22.9) | 11.71 | <0.001 |

| Relapse | 40 (10.5) | 60 (17.1) | 6.75 | 0.009 |

| Rehospitalization | 34 (8.9) | 53 (15.1) | 6.67 | 0.009 |

3.2. Psychiatric symptoms, social functionality, and quality of life scale score

Table 3 shows the results for PANSS, WHO-DAS and QOLS. Repeated measures ANOVA analysis indicated statistically better outcomes over the 24-month period in the total PANSS score, the PANSS negative syndrome score, the WHO-DAS total score, and in the daily life, family life and sense of security subscales scores of the QOLS. In most cases these differences became more evident over time and were greatest at the time of the 12-month and 24-month follow-up evaluations.

Table 3.

Mean (sd) results for Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), WHO Disability Assessment Scale (WHO-DAS) and Quality of Life Scale (QOLS) for 380 patients in the case management (intervention) group and 350 patients in the control group at baseline and at five follow-up points

| Scale/subscale | Group | Baseline | 3 month | 6 month | 9 month | 12 month | 24 month | Fa | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PANSS total score | intervention | 51.5 (16.8) | 50.4 (16.3) | 50.0 (16.1) | 49.2 (15.7)) | 47.9 (17.8)b | 45.1 (17.1)b | 4.81 | <0.001 |

| control | 52.3 (15.9) | 52.3 (16.3) | 51.5 (16.7) | 51.7 (16.8) | 51.7 (16.9) | 51.6 (18.8) | |||

| F | 0.07 | 0.29 | 0.07 | 0.28 | 2.64 | 2.97 | |||

| p | 0.899 | 0.636 | 0.892 | 0.607 | 0.044 | 0.038 | |||

| PANSS positive syndrome score | intervention | 11.5 (4.9) | 11.5 (4.7) | 11.3 (5.3) | 11.2 (5.4) | 11.3 (5.2) | 11.0 (5.1) | 0.07 | 0.740 |

| control | 11.5 (4.9) | 11.4 (5.7) | 11.5 (5.2) | 11.4 (5.5) | 11.6 (5.5) | 11.8 (5.1) | |||

| F | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | |||

| p | 0.930 | 0.923 | 0.916 | 0.924 | 0.915 | 0.911 | |||

| PANSS negative syndrome score | intervention | 17.9 (6.0) | 17.7 (5.7) | 17.5 (6.1) | 16.2 (6.3) | 14.3 (6.6) | 12.2 (6.1)c | 4.32 | <0.001 |

| control | 15.4 (6.2) | 15.3 (6.5) | 15.9 (6.8) | 16.1 (7.3) | 16.3 (7.5) | 16.2 (7.1) | |||

| F | 1.88 | 1.82 | 1.87 | 0.02 | 1.81 | 3.79 | |||

| p | 0.1039 | 0.1721 | 0.1267 | 0.9281 | 0.1904 | 0.001 | |||

| PANSS general psychopathology score | intervention | 25.4 (8.4) | 25.2 (8.2) | 25.4 (8.3) | 25.1 (8.5) | 25.1 (8.1) | 24.9 (8.2) | 0.89 | 0.390 |

| control | 25.3 (7.7) | 25.6 (8.1) | 25.8 (8.4) | 25.6 (8.4) | 25.4 (7.9) | 25.5 (7.4) | |||

| F | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.31 | |||

| p | 0.919 | 0.921 | 0.904 | 0.913 | 0.930 | 0.573 | |||

| WHO-DAS | intervention | 6.5 (0.4) | 6.3 (0.5) | 6.3 (0.3) | 5.8 (0.4) | 4.5 (0.3)b | 4.3 (0.2)b | 2.79 | 0.033 |

| control | 6.1 (0.4) | 6.1 (0.5) | 6.4 (0.7) | 6.4 (0.9) | 6.7 (1.1) | 6.5 (0.9) | |||

| F | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.29 | 2.95 | 2.87 | |||

| p | 0.888 | 0.914 | 0.916 | 0.620 | 0.038 | 0.040 | |||

| QOLS daily life subscale score | intervention | 14.4 (3.8) | 14.6 (3.7) | 14.6 (3.7) | 15.9 (3.9) | 17.2 (4.4) | 18.4 (4.8)b | 3.79 | 0.001 |

| control | 15.8 (3.9) | 15.7 (4.0) | 16.1 (4.3) | 16.7 (3.9) | 16.3 (4.1) | 16.6 (4.1) | |||

| F | 0.27 | 0.16 | 2.32 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 2.94 | |||

| p | 0.599 | 0.701 | 0.079 | 0.681 | 0.681 | 0.037 | |||

| QOLS family life subscale score | intervention | 12.0 (3.0) | 12.3 (2.8) | 12.9 (3.3) | 12.6 (3.1) | 13.6 (3.2) | 14.8 (3.5)b | 3.22 | 0.015 |

| control | 12.1 (2.9) | 12.7 (3.2) | 11.4 (3.7) | 12.6 (3.6) | 12.3 (3.1) | 12.4 (3.1) | |||

| F | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 3.10 | |||

| p | 0.933 | 0.893 | 0.646 | 0.905 | 0.642 | 0.034 | |||

| QOLS social relationships subscale score | intervention | 7.2 (3.0) | 7.2 (3.1) | 7.6 (3.7) | 7.4 (3.5) | 7.4 (3.3) | 7.5 (3.2) | 0.04 | 0.875 |

| control | 7.3 (3.1) | 6.8 (3.4) | 6.6 (3.8) | 6.9 (3.5) | 7.2 (3.6) | 7.1 (3.5) | |||

| F | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.06 | |||

| p | 0.925 | 0.812 | 0.602 | 0.675 | 0.914 | 0.834 | |||

| QOLS financial status subscale score | intervention | 7.5 (1.7) | 7.3 (1.6) | 7.5 (1.4) | 7.2 (2.1) | 7.6 (1.8) | 7.5 (1.9) | 0.02 | 0.930 |

| control | 7.2 (2.1) | 6.8 (1.7) | 7.0 (2.3) | 6.9 (2.1) | 7.1 (2.5) | 7.0 (2.6) | |||

| F | 0.07 | 0.28 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.07 | |||

| p | 0.789 | 0.625 | 0.828 | 0.872 | 0.805 | 0.799 | |||

| QOLS working status subscale score | intervention | 8.9 (1.9) | 9.3 (2.1) | 9.1 (2.2) | 9.3 (1.9) | 9.2 (2.3) | 9.4 (1.7) | 0.47 | 0.174 |

| control | 9.1 (2.1) | 8.9 (2.3) | 9.0 (2.5) | 8.9 (2.1) | 9.0 (1.8) | 8.7 (1.9) | |||

| F | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 1.03 | |||

| p | 0.925 | 0.917 | 0.934 | 0.833 | 0.916 | 0.144 | |||

| QOLS sense of security subscale score | intervention | 3.1 (0.2) | 3.5 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.5) | 4.2 (0.7)b | 4.4 (0.4) | 4.9 (1.0)b | 3.12 | 0.025 |

| control | 3.1 (0.4) | 2.9 (0.7) | 3.0 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.6) | 2.6 (0.5) | 2.1 (0.3) | |||

| F | 0.01 | 1.17 | 0.06 | 1.99 | 2.22 | 2.99 | |||

| p | 0.988 | 0.219 | 0.807 | 0.106 | 0.085 | 0.032 | |||

aF value comparing within-group difference (over time) of the overall model from repeated-measures ANOVA

bp<0.05 - within group difference (vs. baseline)

cp<0.01- within group difference (vs. baseline)

3.3. Analysis on the factors related to the discontinuation of medication

Some patients need to change medications because of serious side effects but most patients discontinue their medication for other reasons. This is universally recognized as one of the most important determinants of relapse so it is helpful to understand the factors that are associated with self-determined drug discontinuation. To determine the factors associated with self-determined discontinuation of medication (defined in this study as stopping antipsychotic medication without physician approval for one month or longer at any time during the 2-year follow-up), and to determine whether or not case management has an independent effect of discontinuation, we conducted a logistic backward stepwise regression with self-determined medication discontinuation as the dependent variable and group membership, gender, age, education level, duration illness, type of medication (i.e., typical or new atypical), high (versus low) mean chlorpromazine-equivalent dosage of medication (dichotomized at 400mg/d), family member supervision of medication, and medication tolerance (overall assessment over the 2 year follow-up by the evaluating clinician) as the independent variables. As shown in Table 4, five variables remained in the final model, indicating that they independently affected discontinuation of medication. (1) Individuals participating in the case management program were significantly less likely to discontinue medication than those in the control group. (2) Patients with higher level of education were more likely to discontinue than those with less education. (3) Patients who supervised medication themselves were more likely to discontinue medication than those for whom coresident family members supervised the use of medication. (4) Patients on higher dosages of medication were more likely to discontinue medications than those on lower dosages. (5) Patients who experienced greater medication-related discomfort were more likely to discontinue medications than who experienced less discomfort; there was a clear stepwise increase in risk of discontinuation as the level of discomfort increased.

Table 4.

Factors associated with ‘self-determined’ discontinuation of antipsychotic medication during two years of treatment in 380 patients with schizophrenia who received case management and 350 patients who received treatment as usuala

| Odds ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Received case management | 0.20 | 0.07-0.62 | 0.005 |

| Educational level | |||

| middle school or below | 1.00 | --- | --- |

| high school | 2.04 | 1.27-7.28 | 0.032 |

| college | 2.83 | 0.99-6.21 | 0.052 |

| Medication not supervised by family member | 5.05 | 1.31-12.17 | 0.026 |

| High mean chlorpromazine-equivalent dosage (>400mg/day) | 6.31 | 1.98-21.99 | 0.029 |

| Tolerance of medication | |||

| no discomfort | 1.00 | --- | --- |

| mild discomfort | 1.17 | 0.94-12.60 | 0.053 |

| moderate discomfort | 3.10 | 1.56-16.63 | 0.038 |

| severe discomfort | 7.76 | 2.33-37.23 | 0.010 |

aFactors considered in the backward stepwise regression include group membership, gender, age, education level, duration of illness, type of medication (i.e., typical or new atypical), high (versus low) mean chlorpromazine-equivalent dosage of medication, family member supervision of medication, and medication tolerance (overall mean assessment or the 2-year period by treating clinician).

4. Discussion

4.1. Key findings

This two-year follow-up study in a relatively large sample of community dwelling individuals with schizophrenia found that compared to treatment as usual a case management program involving monthly training visits with patients and their co-resident family members resulted in significantly lower rates of medication discontinuation, significantly less severe negative symptoms, lower relapse rates and lower rehospitalization rates. Other factors that had an independent effect on discontinuation of medication over the two-year follow-up period included educational level (those with a high educational level were more likely to discontinue medication), lack of family supervision of medication, higher dosage of medication, and greater medication-related discomfort (i.e., side effects). These results highlight the need to involve family members in the management of patients' medication, to use the minimum effective dosage of medication, and to aggressively manage side-effects – even those side effects that pose no medical risks for the patient. The reasons individuals with higher levels of education were more likely to discontinue medication are unknown; further research will be needed to understand this relationship and to modify individualized case management strategies accordingly.

4.2. Limitations

The major limitations of this study are that group assignment was not random and that evaluation of the outcome measures was conducted by team members who knew the group assignment of the participants (i.e., it was not a ‘blind’ evaluation). The matching of intervention group subjects with control group subjects we used to balance potential confounders was not complete (we did not have the time to identify matched controls for the last 30 subjects enrolled in the intervention group). However, there were no significant differences in the main demographic and clinical measures at baseline between groups so we do not believe that the failure to randomize participants had a substantial effect on our outcome measures. Two of the main outcome measures – medication discontinuation and rehospitalization – were easily observable events, so it is unlikely that the lack of blinding of raters would have affected these outcomes. However, other measures such as the PANSS, QOLS, and WHO-DAS scale require clinician judgment, so the possibility that the scores were biased in favor of the case management treatment cannot be definitively excluded. Other limitations are that the selected sample only included individuals who were already registered in registry of mentally ill individuals operated by the Center for Disease Control who resided in two districts of Shanghai that have high-quality health care services, regular follow-up of all individuals with serious mental illnesses every three months and free medication. The results may be different in community residents with schizophrenia who are not in the formal registry, for those who live in communities with less developed health care services, and for those living in communities where free medications are not available for persons with serious mental illnesses.

4.3. Implications

Family intervention, a key component of case manage-ment during rehabilitation, plays a vital role in the improvement of social functioning and reintegration of individuals with schizophrenia. Case management involves an iterative process of assessing each patient's strengths and weaknesses, providing regular and ongoing training (typically targeted on medication management, activities of daily living and social functioning), periodically re-assessing patients' functioning, and making mid-course corrections in the training package.[12]-[15] Given that discontinuation of medication is the main reason for relapse and rehospitalization,[16],[17] training patients and their co-resident family members about adherence and providing them with psychological support for adherence (even in the presence of discomfort and side-effects) is the cornerstone of successful case management interventions. Many factors affect the adherence to medication, including the psychosocial characteristics of the patient and the patient's co-resident family members, fluctuations in disease symptomatology, the type and dosage of antipsychotic medication used, and the patient's tolerance of the medication.[18],[19] It is important to make ongoing assessments of these factors during the follow-up of each patient and to actively address them as part of each patient-specific case management plan.

Case-management of persons with serious mental illness requires a substantial investment of professional personnel. But it also results in substantial improvement of patients' functioning and a resultant decrease in the usage of inpatient services. Cost-benefit analyses are needed to determine the potential costs and benefits of up-scaling this type of service to other urban and rural parts of China.

Biography

Meijuan Chen obtained her degree in clinical medicine from Suzhou Medical College in 1983 and has been working at the Shanghai Mental Health Center as a psychiatrist since then. She is currently a chief doctor and a board member of the Geriatric Psychiatry Chapter of the China Association for Mental Health. Her main research interest is clinical and community rehabilitation of schizophrenia.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the Shanghai Municipal Hospital Comprehensive Prevention and Control of Chronic Diseases project (SHDC12007314).

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Wang CH, Qu YG. [The working organization and content of Shanghai psychosis prevention] Yi Xue Yan Jiu Za Zhi. 1982;2:7–9. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li YH, Yao XW, Zhang MY. [The study and countermeasures on the institutional status of Shanghai psychiatric rehabilitation institution] Shanghai Jing Shen Yi Xue. 2005;17(suppl):35–37. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2005.z1.015. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang MY. [Policy documents of the mental health work in China - Interpretation of “Guiding opinions on the further strengthening on mental health work”] Shanghai Jing Shen Yi Xue. 2005;17(suppl):1–2. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holloway F, Oliver N, Collins E, Carson J. Case management: A critical review of the outcome literature .European Psychiatry. null. 1995;10(3):113–128. doi: 10.1016/0767-399X(96)80101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott JE, Dixon LB. Assertive community treatment and case management for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull. 1995;21(4):657–668. doi: 10.1093/schbul/21.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mueser KT, Bond GR, Drake RE, Resnick SG. Models of community care for severe mental illness and a review of research on case management. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1998;24(1):37–74. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song LS, Chen MJ, Li WJ, Sun J, Ke SJ. [Assessment of the community patients’ need with chronic schizophrenia] Shanghai Jing Shen Yi Xue. 1999;11(2):65–69. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weng YZ. [Operation manual of schizophrenia rehabilitation] Beijing: People’s Health Publishing House; 2009. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Si TM, Yang JZ, Shu L, Wang XL, Kong QM, Zhou M, et al. [The reliability, validity of PANSS and its implication] Zhongguo Xin Li Wei Sheng Za Zhi. 2004;18(1):45–47. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:1000-6729.2004.01.016. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. International Classification of functioning, disability and health-ICF. Geneva: WHO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song LS, Zhang MY, Wu HM, Xu LQ. [Preparation and testing of the quality of life scale (QOLS) in community mental disorders] Shanghai Jing Shen Yi Xue. 1996;8(4):255–257. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith L, Newton R. Systematic review of case management. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;41(1):2–9. doi: 10.1080/00048670601039831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burns T, Fioritti A, Holloway F, Malm U, Rössler , W Case management and assertive community treatment in Europe. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(5):631–636. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.5.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark T, Kenney-Herbert J, Humphreys MS. Community rehabilitation orders with additional requirements of psychiatric treatment. APT. 2002;8:281–288. doi: 10.1192/apt.8.4.281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang LR, Lin YH, Chang HC, Chen YZ, Huang WL, Liu CM, et al. Psychopathology, rehospitalization and quality of life among patients with schizophrenia under home care case management in Taiwan. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 2013;112(4):208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malakouti S, Nojomi M, Panaghi L, Chimeh N, Mottaghipour Y, Joghatai M, et al. Case-management for Patients with Schizophrenia in Iran: A Comparative Study of the Clinical Outcomes of Mental Health Workers and Consumers’ Family Members as Case Managers. Community Mental Health Journal. 2009;45(6):447–452. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9197-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stefan L, Magdolna T, Katja K, Heres S, Kissling W, Salanti , G , et al. Antipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9831):2063–2071. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephen A, Martin K, Clement F, Mondher T, Traolach B. Relapse in schizophrenia: costs, clinical outcomes and quality of life. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:346–351. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.4.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antonio V, Stefano B, Giacomo D, Paola C, Luca DP, Emilio S. Factors related to different reasons for antipsychotic drug discontinuation in the treatment of schizophrenia: A naturalistic 18-month follow-up study. Psychiatry Research. 2012;200(2-3):96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]