Abstract

House-resting Anopheles mosquitoes are targeted for vector control interventions; however, without proper species identification, the importance of these Anopheles to malaria transmission is unknown. Anopheles longipalpis, a non-vector species, has been found in significant numbers resting indoors in houses in southern Zambia, potentially impacting on the utilization of scarce resources for vector control. The identification of An. longipalpis is currently based on classical morphology using minor characteristics in the adult stage and major ones in the larval stage. The close similarity to the major malaria vector An. funestus led to investigations into the development of a molecular assay for identification of An. longipalpis. Molecular analysis of An. longipalpis from South Africa and Zambia revealed marked differences in size and nucleotide sequence in the second internal transcribed spacer (ITS2) region of ribosomal DNA between these two populations, leading to the conclusion that more than one species was being analysed. Phylogenetic analysis showed the Zambian samples aligned with An. funestus, An. vaneedeni and An. parensis, whereas the South African sample aligned with An. leesoni, a species that is considered to be more closely related to the Asian An. minimus subgroup than to the African An. funestus subgroup. Species-specific primers were designed to be used in a multiplex PCR assay to distinguish between these two cryptic species and members of the An. funestus subgroup for which there is already a multiplex PCR assay.

Keywords: Anopheles longipalpis, Anopheles funestus, South Africa, Zambia, internal transcribed spacer (ITS2), PCR, phylogenetics

Introduction

Anopheles longipalpis Theobald was originally described in 1903 from Zomba, Malawi (Theobald, 1903) and has subsequently been recorded from Sudan, Ethiopia, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, Angola, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and South Africa (Gillies & De Meillon, 1968; White, 1972; Gillies & Coetzee, 1987). It is very similar in adult morphology to the major African malaria vector Anopheles funestus Giles although quite distinct in the larval stage.

Very little has been recorded on the adult biology of this species. It has been collected feeding on humans outdoors in small numbers and rarely resting inside houses (Gillies & Coetzee, 1987). More recently, however, it has been found in large numbers resting inside houses in Zambia with a small number feeding on humans indoors, but cattle being the preferred host (Kent et al., 2006). The species has never been implicated as a vector of malaria (Gillies & De Meillon, 1968; Gillies & Coetzee, 1987; Kent et al., 2006).

During an outbreak of malaria in South Africa in 2004, An. funestus-like mosquitoes were collected by window exit traps from houses, leading to concerns that insecticide resistant An. funestus had returned to the country as happened in 1999 (Hargreaves et al., 2000). The specimens were subsequently identified as An. leesoni Evans and An. longipalpis. This discovery, together with the Zambian situation, has implications for malaria vector control programmes where correct identification of the vector species is critical for policy making, malaria epidemiology and the monitoring and surveillance of vector populations. Furthermore, the observation that An. longipalpis falsely appeared as an An. vaneedeni Gillies and Coetzee/parensis Gillies hybrid by diagnostic PCR (Kent et al., 2006) suggested a close genetic relationship between this species and the An. funestus subgroup and prompted the need to develop novel specific primers for An. longipalpis to aid in the proper identification of this species. In this paper, we report on a molecular study undertaken on South African and Zambian An. longipalpis. Molecular analysis revealed the presence of two molecular types (A and C) within An. longipalpis, and these are compared with members of the An. funestus subgroup.

Materials and methods

Mosquito collection and morphological identification

South Africa

Field work was conducted in January 2004 in the Lydenburg District, Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Mosquitoes were collected using window exit traps and house searches in Ohrigstad (24°44′S, 30°33′E). Live mosquitoes were brought back from the field, induced to lay eggs, and adults were reared under standard insectary conditions (Hunt et al., 2005). Females were identified according to Gillies & Coetzee (1987) and stored on desiccant for molecular analysis.

Zambia

Mosquitoes were collected in the Macha region (16°46′S; 26°94′E) of the Southern Province of Zambia by aspiration and pyrethrum spray catch (Kent et al., 2006). Specimens were identified morphologically, as described above, and stored on desiccant for molecular analysis.

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from specimens (Collins et al., 1987), and each set of extractions contained a positive control (colonised An. funestus) as well as a ‘no DNA’ control containing no mosquito. The DNA pellet was resuspended in 100 μl 1× TE buffer and a sub-sample (0.5 μl) was used as template for the PCR reactions.

Amplification, sequencing and cloning

An. funestus group multiplex PCR

The species-specific PCR assay to identify members of the An. funestus group was used (Koekemoer et al., 2002).

ITS2 PCR

The ITS2 region of the rDNA was amplified using the following primers: ITS2A: 5′-TGTGAACTGCAGGACA-CAT-3′; and ITS2B: 5′-TATGCTTAAATTCAGGGGGT-3′. PCR conditions were as for the An. funestus species-specific PCR (Koekemoer et al., 2002). ITS2A are located on the 5′ end of the 5.8S gene, and ITS2B are located on the 3′ end of the 28S gene, and the ITS2 region is located in between these two genes. Amplicons were electrophoresed on 1.5% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide (3 mg μl−1), and size was confirmed using a molecular weight marker (O’RangeRuler 100 bp DNA ladder, Fermentes Life Sciences).

Sequencing

ITS2 PCR products were purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit Protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and sequenced directly. Those samples resulting in poor quality sequence were cloned and subsequently sequenced as described below. Cycle sequencing was done by using BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit according to manufacturer’s recommendations, followed by purification of products using DyEx spin (Qiagen). Sequences were generated using the ABI Prism 310 sequencer. Novel consensus sequences were deposited on GenBank: An. longipalpis Type A (DQ910534); An. longipalpis Type C, (EF136463, EF095767). Due to a lack of sufficient molecular data to elucidate An. longipalpis Type B (Koekemoer, unpublished data), this was not included in the current paper and we focused on Types A and C only.

Sequence analysis and primer design

DNASTAR® (Lasergene v6, Wisconsin, USA) was used for sequence analysis. Anopheles longipalpis-specific primers were designed after sequence alignment. Primer annealing sites were critically placed where nucleotide differences were found between Types A and C and the members of the An. funestus group. Amplicon sizes for species identification had to differ by at least 50 bp to allow easy differentiation between amplicons by agarose electrophoresis. General primer criteria, such as GC content, were also taken into consideration.

Cloning

Type A (n = 1) and Type C (n = 4) An. longipalpis specimens were cloned prior to sequencing. PCR amplicons were purified using QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia) and cloned using the pGEM® – T Easy Vector System 1 (Promega, USA). Plasmid purification was carried out on transformed clones using Qiagen’s plasmid purification kit (cat no: 12125) and sequenced using T7 (5′-GTAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3′) and SP6 (5′-TACG-ATTTAGGTGACACTATAG-3′) primers.

An. longipalpis multiplex PCR

Two molecular types were identified after analysing sequences. Type A identifies An. longipalpis from South Africa, and Type C correlates to specimens from Zambia. Two new primers, A3 and C1, were manually designed based on sequence alignment analysis, and Primer Select (DNASTAR inc, USA) was used to confirm Tm-values and self-complementarities. These primers were found to be specific for Types A and C, respectively, and they produced the expected band sizes (table 1). PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 min, 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 45°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s and extension at 72°C for 10 min. Each 25 μl PCR reaction contained the following: 2.5 μl of 10× reaction buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.3, 500 mM KCl), 200 μM of each dNTP, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 6.6 pmol per primer, 2 units Taq DNA polymerase.

Table 1. Anopheles longipalpis.

type specific primers and their respective sequences, Tm temperatures and estimated fragment sizes.

| Primer name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Tm (°C) | Fragment size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Universal (F) | TGT GAA CTG CAG GAC ACA T | 58 | |

| Long A 3 (R) | TGA AGA TCT GAG ACC CCG GC | 57.7 | 328 bp |

| Long C1 (R) | CCA AGC ACG TTG ATC CAG TAT TAC | 54.5 | 439 bp |

Phylogenetic analysis

The following ITS2 sequences with accession numbers were included in the phylogenetic analysis: An. funestus (AF062512); An. parensis (AY035720); An. rivulorum (AF210724); An. vaneedeni (AY035718); An. leesoni (AY255107); An. longipalpis Type A (DQ910534); An. longipalpis Type C, small fragment (EF136463); An. longipalpis Type C, large fragment (EF095767); An. fluviatilis form V (Chen et al., 2006) (DQ344526); An. minimus s.s (DQ336436) (formally known as Type A: Harbach et al., 2006); An. harrisoni (formally known as An. minimus C) (Harbach & Manguin) (AF230462); An. varuna Iyengar (AF230465); and An. pampanai Büttiker & Beales (AF230464). A multiple alignment was completed using MultAlin (Corpet, 1988). This alignment was manually corrected and imported into PAUP*version Beta 10 (Swofford, 2003). Maximum Parsimony (MP) and Maximum Evolution (neighbour-joining, NJ) phylogenetic trees were constructed using heuristic search methods and tree bisection reconnection (TBR) branch swapping algorithm. Branch support was determined using 1000 bootstrap replicates (Felsenstein, 1985).

Results

Species identification

Apart from An. leesoni of the An. funestus group, only one specimen of An. longipalpis was collected from Lydenburg in South Africa. This specimen was morphologically identified as An. longipalpis and gave no amplicon with the An. funestus group species-specific PCR. A total of 50 An. longipalpis specimens from the Zambian collection were identified morphologically (along with An. funestus s.s. (Kent et al., 2006)) and used in this study. These specimens resulted in hybrid amplicons for An. vaneedeni/An. parensis with the An. funestus group species-specific PCR as reported by Kent et al. (2006).

Amplification of the ITS2 region

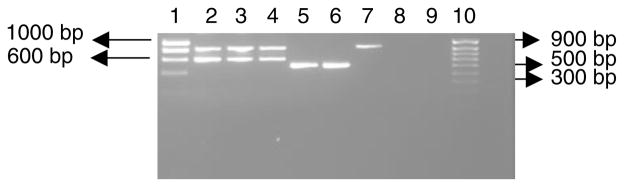

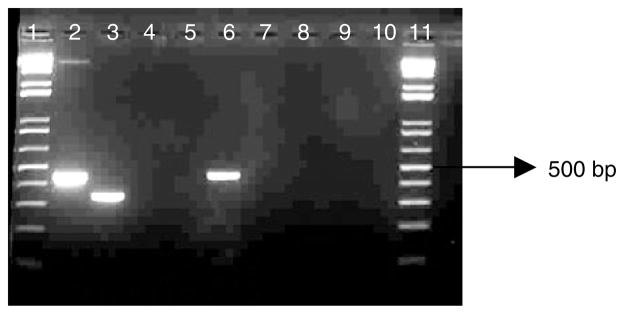

Amplification using the ITS2 primer pair (fig. 1) resulted in a ~500 bp fragment from An. longipalpis from South Africa (called Type A) and two amplicons, a small fragment of ~600 bp and a large fragment of ~850 bp, from An. long-ipalpis from Zambia (called Type C). Initially, it was thought that the two fragments observed might be due to either two primer binding sites within the ITS2 sequence or an indication that non-specific fragments were amplified. The latter was investigated by optimising annealing temperatures, ranging between 40–62°C. No amplification was achieved at 62°C, but all other temperatures produced two distinct fragments. In addition, magnesium chloride concentrations were varied between 0.5–2.5 mM at an annealing temperature of 60°C, and again two distinct fragments were produced. These fragments, therefore, are most likely due to specific primer binding to the DNA template and not to non-specific binding. As a result, subsequent investigations treated these as two separate products, and they were analysed accordingly.

Fig. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of ITS2 PCR products from An. longipalpis. Lanes 1 and 10, Hyper ladder I and Hyper ladder IV, respectively; lanes 2–4, Type C; lanes 5 and 6, Type A; lane 7, An. funestus; lane 8, PCR negative control; and lane 9, DNA extraction negative control.

ITS2 sequence analysis

Type A (accession number: DQ910534)

Only one wild An. longipalpis female was obtained from South Africa. The F1 progeny from this female were used for molecular analysis(n = 8) and sequencing (n = 2). Analysis of Type A revealed some sequence similarities with the Asian mosquito, An. varuna Lyengar (accession number: AF230465), when using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). The 5.8S region located on the 5′ end (1–117 bp) showed close similarity (96%) between these two species. The last 48 bp on the 3′ end (470–517 bp), representing the 28S region, showed 97%similarity to this Asian species. Locations of the 5.8S, ITS2 and 28S genes are based on annotations from another Asian mosquito, An. fluviatilis form V, which also showed high percentage (71%) similarity to Type A. As a result, these species and other closely related Asian mosquitoes were utilized in the phylogenetic analysis.

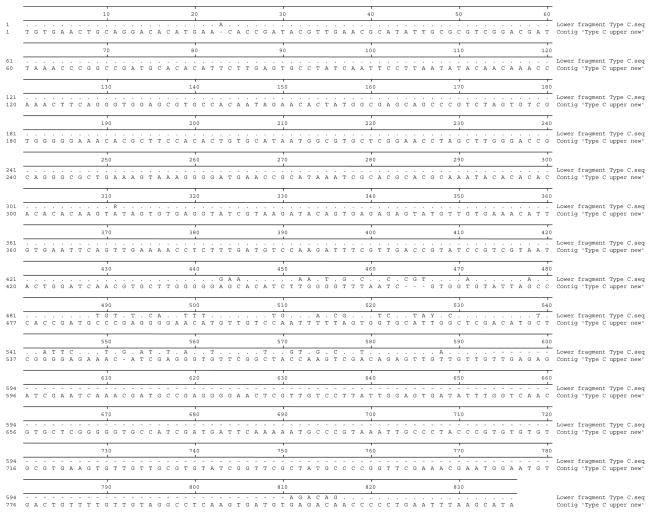

Type C

The small fragment (601 bp; accession number: EF136463) showed close similarity with An. parensis (AY259148.1) with approximately 94% identity over almost the full-length sequence (alignment data not shown). The large fragment (831 bp; accession number: EF095767) on the other hand, showed 97.5% similarity with partial 5.8S, ITS2 and 28S sequences of An. vaneedeni (AY035718) over the length of the sequence (data not shown).

To understand the relationship between the two fragments, multiple sequence alignment comparisons were performed (fig. 2). The fragments showed high similarity (91% over the complete length) to each other but with the large fragment containing an additional 216 bp. Both sequences are highly similar, however variations were observed between positions 443 bp and 579 bp. The small fragment shows a deletion of 216 bp from positions 594–810 bp. Anopheles longipalpis has previously shown double amplicons when analysed with the An. funestus species-specific PCR assay (Kent et al., 2006). However, An. longipalpis from South Africa did not amplify any products when used in the An. funestus group species-specific PCR assay, unlike Type C from Zambia (fig. 3). This was due to no sequence similarity to the species-specific primers used in this assay. The faint bands observed in fig. 3 (~900 bp) were due to non-specific binding that appeared at the annealing temperature of 45°C, which is the standard temperature used when the An. funestus multiplex PCR assay is performed.

Fig. 2.

Multiple sequence alignment between the Type C large and small ITS2 amplicons. Both sequences are highly similar; however, between position 443 bp and 588 bp variations are observed. The small fragment shows a deletion of 216 bp from position 594–810 bp.

Fig. 3.

Amplified fragments using the An. funestus group species-specific PCR of Koekemoer et al. (2002). Lanes 1–10, An. longipalpis Type C; lanes 4 and 9, no amplification; lane 2, shows a faint large fragment; however, when the sample was repeated, the large fragment was clearly visible; lanes 11–16, Type A; lane 17, An. vaneedeni; lane 18, An. funestus (no amplification on this gel due to human error, expected size: 500 bp); lane 19, An. rivulorum; lane 20, An. parensis; lane 21, An. leesoni; lane 22, DNA extraction negative control; lane 23, PCR mastermix negative control with no template; and lane 24, Hyperladder IV (100 bp) molecular marker.

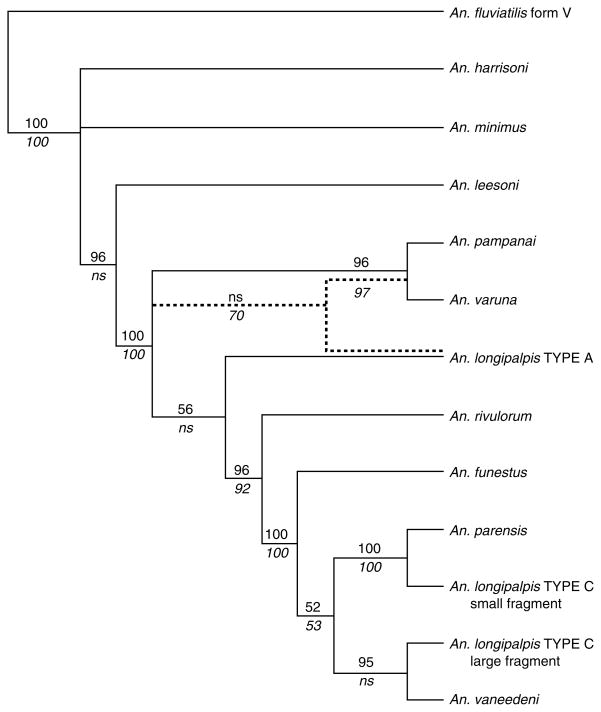

Phylogenetic analysis

ITS2 sequences were analysed to determine the relationship between Types A and C of An. longipalpis and with those of the An. funestus group and other Asian species (fig. 4). The resulting phylogeny (fig. 5), based on 497 bp of aligned sequences, showed a close relationship between the Type C large fragment and An. vaneedeni using distance analysis, but this relationship was not supported by parsimony analysis. In contrast, the small fragment formed a clade with An. parensis that was supported strongly by both analyses. Both large and small fragments of Type C grouped exclusively with the An. funestus subgroup (An. funestus, An. vaneedeni, An. parensis), whereas Type A grouped close to An. leesoni and An. rivulorum. Parsimony analysis strongly (bootstrap = 70) places Type A, An. pampanai and An. varuna on the same branch. This configuration is not supported by the neighbour-joining analysis that only weakly (bootstrap = 56) places Type A more derived from these same taxa. It is also notable that parsimony analysis does not support the more derived status of An. leesoni from An. minimus and An. harrisoni, as indicated strongly by NJ analysis.

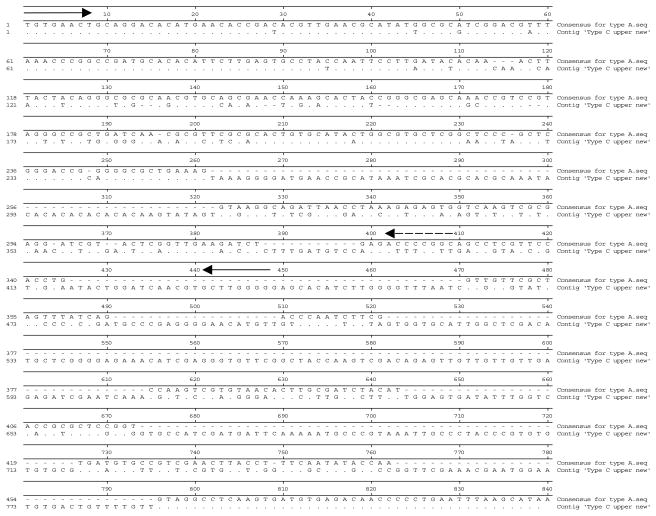

Fig. 4.

Multiple sequence alignment between Types A and C large ITS2 fragment of An. longipalpis. Forward primer is indicated by a solid line arrow, A3 reverse primer is indicated by dashed line arrow, and C1 reverse primer is shown as solid line arrow. (.) indicates where the same nucleotide is found at a specific position; (−) indicates the absence of a nucleotide at that particular position.

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic tree predicted from the ITS2 multiple sequence alignment. Branch length indicates relative genetic distance. Bootstrap support > 50% from neighbour-joining (above) and parsimony (below) analyses are indicated for each branch. ‘ns’ indicates ‘no support’.

Design of species-specific primers

Due to sequence similarities displayed between the large and small fragments amplified from An. longipalpis, it was decided to utilize the large fragment for the designing of species-specific primers to distinguish between Type A and Type C. Sequence alignment between Type A and Type C (fig. 4) indicated potential sites for primer design. Arrows indicate the positions of the forward and reverse primers. The forward primer is the same as that used in the An. funestus group species-specific PCR assay (Koekemoer et al., 2002). Primer sequences and relevant information are summarized in table 1.

PCR conditions were optimized using the sample from South Africa representing Type A, and Zambian samples used for sequencing of Type C. Other members of the An. funestus group were included to confirm primer specificity (fig. 6). The new primers, A3 and C1, were tested on wild-caught An. longipalpis from Zambia (n = 50), presumed to be Type C. A total of 48 samples were identified as Type C. Two samples failed to amplify at all, which may have been due to DNA degradation.

Fig. 6.

Cocktail PCR to identify the two genetic forms of An. longipalpis. Lane 1 and 11, 1 Kb molecular weight marker; lane 2, An. longipalpis Type C (Clone LCa); lane 3, An. longipalpis Type A (DNA template); lane 4, An. leesoni; lane 5, An. parensis; lane 6, An. longipalpis Type C (Clone LCb); lane 7, An. rivulorum; lane 8, An. funestus; lane 9, An. vaneedeni; lane 10, PCR negative control.

Discussion

The original aim of this project, based on the possible confusion of An. longipalpis adults with An. funestus, was to develop a primer set to be incorporated into the An. funestus multiplex PCR (Koekemoer et al., 2002) for identification of members of the An. funestus group. However, in the process of characterizing An. longipalpis at the molecular level, distinct genetic differences were noted within (data not included) and between the Zambian population and the single wild specimen from South Africa.

Cryptic species in the An. rivulorum subgroup have been identified previously based on sequencing analysis, e.g. An. rivulorum in West Africa (An. rivulorum-like) (Hackett et al., 2000; Cohuet et al., 2003). Analysis between An. rivulorum-like from West Africa and An. rivulorum from southern Africa revealed specific nucleotide differences in the ITS2 region that can be used to distinguish between them with ~19% divergence being recorded (Hackett et al., 2000; Cohuet et al., 2003). This is far higher than the intra-specific variance (~0.2%) reported for An. funestus (Mukayabire et al., 1999) or even inter-specific divergence (0.4–1.6%) between members of the An. gambiae complex (Paskewitz et al., 1993). Sequence divergence between An. longipalpis from Zambia and South Africa was 33.7% (for large amplicon) and 38.9% (small amplicon), almost twofold greater than that recorded in the An. rivulorum subgroup and clearly indicative of a separate species.

Sequence analysis of the 5.8S and 28S regions, but not of the ITS2 region, in An. longipalpis Type A from South Africa revealed close similarity to the Asian mosquitoes An. varuna (a member of the An. aconitus subgroup) and An. fluviatilis complex (a member of the An. minimus subgroup) (Harbach, 2004). While An. leesoni is included in the An. funestus group by Gillies & De Meillon (Gillies & Coetzee, 1987), subsequent chromosomal (Green, 1982) and molecular (Garros et al., 2005a,b) analyses place this species more precisely within the Asian An. minimus subgroup. Interestingly, the An. longipalpis Type A ITS2 sequence groups most closely with An. pampanai and An. varuna, with all three sequences clustering clearly between An. leesoni to the basal side and An. rivulorum to the more derived orientation. Based on work done by Garros et al. (2005b), Type A would group within the Minimus clade.

In contrast, sequence analysis of the ITS2 region of Type C from Zambia results in a grouping with An. vaneedeni and An. parensis, two members of the An. funestus subgroup (Gillies & Coetzee, 1987; Harbach, 2004). Anopheles vaneedeni and An. parensis are almost identical in all life stages, differing in only very minor and overlapping characteristics (Gillies & De Meillon, 1968). Anopheles longipalpis, however, has very distinct larvae and was not placed in the An. funestus group by Gillies & De Meillon (1968) nor by Harbach (2004). This would seem to indicate extensive evolutionary divergence and is supported by the sequence data for Type A from South Africa. The rDNA profile of the ITS2 region in Type C, possessing sequence similarity to both An. vaneedeni and An. parensis, on the other hand, indicates a genetic relatedness that belies the morphological differentiation. It is possible that during speciation when the rDNA duplicated, it was truncated or extended due to an alteration effect, such as polymerase slippage. This could have produced the current tandem repeat characteristic it has today (fig. 2), and both sequences, or ‘alleles’, then became fixed separately in duplication events of the rDNA in An. vaneedeni and An. parensis. How the same ‘alleles’ from these two species arose in a totally different third species (An. longipalpis Type C) needs further investigation. Studies on ITS2 sequences from other anopheline species within the Myzomyia Series may provide insight into this interesting situation.

When Type C was screened using the An. funestus group species-specific PCR assay (fig. 3), the fragments diagnostic for both An. vaneedeni and An. parensis were observed, as was recorded by Kent et al. (2006). We can now say that this hybrid phenotype observed on agarose gel is the result of specific amplification from two different ITS2 variants from An. longipalpis, each containing sequence similarity to either An. vaneedeni or An. parensis. Based on this evidence, An. longipalpis Type C should, therefore, need to be included into the An. funestus subgroup.

The species-specific primers can successfully be used to distinguish between Type A and Type C but are not useful for separating An. longipalpis from the An. funestus group in the Koekemoer et al. (2002) PCR assay. However, in the routine screening of An. funestus group field collections, those specimens that show a ‘hybrid’ vaneedeni/parensis profile, or that do not amplify at all, should be additionally processed using the An. longipalpis primers.

Conclusion

With the latest initiatives for vector control being implemented by many African countries, the importance of vector identification needs to be emphasized. Monitoring and evaluation of indoor residual spraying (IRS) and use of insecticide impregnated bed nets (ITN) are dependent on correct vector identification to determine their efficacy. Where non-vector anophelines are found resting inside houses, a reliable and rapid method of distinguishing them from the vector species is essential. This study provides a method for the East and southern African populations of An. longipalpis and the An. funestus group.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for EM was obtained from the University of the Witwatersrand Postdoctoral Research Fellowship and the National Research Foundation. Funding for the project was obtained from the South African Medical Research Council. We thank the Mpumalanga Malaria Control Programme for support provided during field collections. Funding for the Zambian collections was provided by the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute.

References

- Chen B, Butlin RK, Pedro PM, Wang XZ, Harbach RE. Molecular variation, systematics and distribution of the Anopheles fluviatilis complex in southern Asia. Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 2006;20:33–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2006.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohuet A, Simard F, Toto J, Kengne P, Coetzee M, Fontenille D. Species identification within the Anopheles funestus group of malaria vectors in Cameroon and evidence for a new species. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2003;69:200–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins FH, Mendez MA, Rasmussen MO, Meheffey PC, Besansky NJ, Finnerty V. A ribosomal RNA gene probe differentiates member species of the Anopheles gambiae complex. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1987;37:37–41. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1987.37.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpet F. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acid Research. 1988;16:10881–10890. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garros C, Harbach RE, Manguin S. Morphological assessment and molecular phylogenetics of the Funestus and Minimus Groups of Anopheles (Cellia) Journal of Medical Entomology. 2005a;42:521–536. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/42.4.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garros C, Harbach RE, Manguin S. Systematics and Biogeographical implications of the phylogenetic relationships between members of the Funestus and Minimus Groups of Anopheles (Diptera: Culicidae) Journal of Medical Entomology. 2005b;42:7–18. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/42.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillies MT, Coetzee M. A Supplement to the Anopheline of Africa South of the Sahara. Johannesburg: South African Medical research Institute for Medical Research; 1987. pp. 1–139. Publication, No. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Gillies MT, De Meillon B. The Anophelinae of Africa, South of the Sahara. 55 Johannesburg: South African Institute of Medical Research; 1968. pp. 1–343. [Google Scholar]

- Green CA. Cladistic analysis of mosquito chromosome data: Anopheles (Cellia) Myzomyia. Journal of Heredity. 1982;73:2–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett BJ, Gimnig J, Guelbeogo W, Costantini C, Koekemoer LL, Coetzee M, Collins FH, Besansky NJ. Ribosomal DNA internal transcribed specer (ITS2) sequences differentiate Anopheles funestus and An. rivulorum, and uncover a cryptic taxon. Insect Molecular Biology. 2000;9:369–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbach RE. The classification of genus Anopheles (Diptera: Culicidae): a working hypothesis of phylogenetic relationships. Bulletin of Entomological Research. 2004;94:537–553. doi: 10.1079/ber2004321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbach RE, Parkin E, Chen B, Butlin RK. Anopheles (Cellia) minimus Theobald (Dipetera: Culicidae): neotype designation, characterization, and systematics. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington. 2006;108:198–209. [Google Scholar]

- Harbach RE, Garros C, Manh ND, Manguin S. Formal taxonomy of species C of the Anopheles minimus sibling species complex (Diptera: Culicidae) Zootaxa. 2007;1654:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves K, Koekemoer LL, Brooke BD, Hunt RH, Mthembu J, Coetzee M. Anopheles funestus resistant to pyrethroid insecticides in South Africa. Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 2000;14:181–189. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2000.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt RH, Brooke BD, Pillay C, Koekemoer LL, Coetzee M. Laboratory selection for and characteristics of pyrethroid resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 2005;17:417–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2005.00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent RJ, Coetzee M, Mharakurwa S, Norris DE. Feeding and indoor resting behaviour of the mosquito Anopheles longipalpis in an area of hyperendemic malaria transmission in southern Zambia. Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 2006;20:459–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2006.00646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koekemoer LL, Kamau L, Hunt RH, Coetzee M. A cocktail polymerase chain reaction assay to identify members of the Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) group. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2002;66:804–811. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukayabire O, Boccolini D, Lochouarn L, Fontenille D, Besansky NJ. Mitochondrial and ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS2) diversity of the African malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Molecular Ecology. 1999;8:289–297. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paskewitz SM, Wesson DM, Collins FH. The internal transcribed spacers of ribosomal DNA in five members of the Anopheles gambiae species complex. Insect Molecular Biology. 1993;2:247–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.1994.tb00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford D. PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods), Ver. 4. Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Theobald FV. A Monograph of the Culicidae or Mosquitoes. London: The British Natural History Museum; 1903. [Google Scholar]

- White GB. Confirmation that Anopheles longipalpis (Theobald) and Anopheles confusus Evans and Leeson occur in Ethiopia. Mosquito Systematics. 1972;4:131–132. [Google Scholar]