Abstract

Aging is associated with the accumulation of ectopic lipid resulting in the inhibition of normal organ function, a phenomenon known as lipotoxicity. Within the bone marrow microenvironment, elevation in fatty acid levels may produce an increase in osteoclast activity and a decrease in osteoblast number and function, thus contributing to age-related osteoporosis. However, little is known about lipotoxic mechanisms in intramembraneous bone. Previously we reported that the long chain saturated fatty acid palmitate inhibited the expression of the osteogenic markers RUNX2 and osteocalcin in fetal rat calvarial cell (FRC) cultures. Moreover, the acetyl Co-A carboxylase inhibitor TOFA blocked the inhibitory effect of palmitate on expression of these two markers. In the current study we have extended these observations to show that palmitate inhibits spontaneous mineralized bone formation in FRC cultures in association with reduced mRNA expression of RUNX2, alkaline phosphatase, osteocalcin, and bone sialoprotein and reduced alkaline phosphatase activity. The effects of palmitate on osteogenic marker expression were inhibited by TOFA. Palmitate also inhibited the mRNA expression of fatty acid synthase and PPAR gamma in FRC cultures, and as with osteogenic markers, this effect was inhibited by TOFA. Palmitate had no effect on FRC cell proliferation or apoptosis, but inhibited BMP-7-induced alkaline phosphatase activity. We conclude that palmitate accumulation may lead to lipotoxic effects on osteoblast differentiation and mineralization and that increases in fatty acid oxidation may help to prevent these lipotoxic effects.

Keywords: Osteoblast differentiation, Palmitate, Fetal rat calvarial cell culture, Lipotoxicity

Introduction

Lipotoxicity refers to the inhibitory effects of lipid on tissue function. Lipotoxicity has been best characterized in metabolic tissues wherein excess lipid inhibits insulin signaling, leading to dysregulated metabolism [1]. However, the toxic effects of lipid include decreased cell viability and differentiation. Recently, bone has been identified as an important site of lipotoxicity, and it has been suggested that lipotoxicity may be a key mechanism in age-related osteoporosis [2,3]. Published results show that lipids cause increased osteoblast apoptosis and inhibit the differentiation of osteoblasts [4,5]. The mechanisms of lipotoxicity in bone are, however, incompletely understood. In bone marrow it is believed that with age, there is a switch from osteoblastogenesis to adipogenesis [2]; and that fatty acids, released from the adipocytes, act in a paracrine manner to inhibit osteoblast function [4–7]. In calvarial cells, on the other hand, there is evidence that osteoblasts co-express adipogenic and osteogenic markers in response to PPARγ agonists [8].

Regardless of the precise change in cellularity, it is evident that lipotoxicity involves the dysregulation of free fatty acid metabolism leading to inhibitory effects on cells [1]. In soft tissues, increased de novo fatty acid biosynthesis and/or ineffective fatty acid oxidation leads to metabolism of fatty acids through alternative pathways resulting in the production of toxic compounds such as ceramides [1]. A key regulator of the balance of fatty acid metabolism is the enzyme, acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACC), which catalyzes the conversion of acetyl CoA to malonyl CoA. Malonyl CoA in turn acts as a switch by providing the substrate for fatty acid biosynthesis and by acting as an allosteric inhibitor of fatty acid oxidation. Thus, acetyl CoA carboxylase inhibition may attenuate lipotoxicity by inhibiting fatty acid biosynthesis and by promoting fatty acid oxidation [9]. Previously we found that palmitate inhibited the expression of two osteogenic markers in FRC cells and that this effect was blocked by the ACC inhibitor TOFA [10]. In the present study we have further tested the hypothesis that stimulation of fatty acid oxidation may attenuate the lipotoxic effects of palmitate on fetal rat calvarial (FRC) cell.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Gemini Bio-Products (Woodland, CA). Alpha MEM (αMEM), Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS), penicillin-streptomycin stock, and trypsin-EDTA were purchased from Gibco/Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Recombinant human BMP-7 was provided by Stryker Biotech (Hopkinton, MA) and dissolved in 47.5% ethanol/0.01% trifluoroacetic acid. TOFA was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI) and Cell Proliferation (MTT) kit was from Promega.

Fetal rat calvarial cell culture

Animals were purchased from Harlan (Madison, WI), housed, and killed according to the protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, TX, USA. Primary osteoblastic cells were prepared from calvariae of 19-day-old fetal rats as described previously [11] and were cultured in αMEM plus 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml of streptomycin sulfate, at 37°C with 5% CO2. For experiments with palmitate and TOFA, FRC cultures were treated as indicated in individual figure legend for 48 h and terminated.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was measured using the CellTiter 96 AQ One Solution Assay kit from Promega (Madison, WI). Absorbance at 490 nm was determined using a MRX II microplate reader (Thermo Labsystems, Chantilly, VA).

RNA extraction and real-time RT-PCR

mRNA expression in FRC cells was analyzed by qRT-PCR as described previously [12]. Total RNA was extracted using RNA-STAT-60 reagent/chloroform, and precipitated with isopropanol. RNA (2.5 μg) was used to synthesize cDNAs with the High-capacity Reverse Transcription kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in the Eppendorf Mastercycler (Westbury, NY). Real-time PCR was performed on the ABI7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System using the universal condition (1 cycle at 50C° for 2 min; 1 cycle at 95°C for 10 min; 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min) and the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Taqman gene expression probes for alkaline phosphatase (AP, Rn01516028_m1), Osteocalcin (OCN, Rn00566386_g1), Bone Sialoprotein (BSP2, Rn00561414_m1), Runx2 (Rn01512298_m1), fatty acid synthase (FAS, Rn00569117_m1), PPARγ (Rn00440945_m1), BMP-7 (Rn01528889_m1), and internal controls β-2-microglobulin (B2M, Rn00560865_m1) were purchased from Applied Biosystems. Target gene expression was normalized to that of B2M; duplicates were determined using the ΔΔCT method.

Alkaline phosphatase (AP) enzymatic activity measurement and protein staining

AP activity was measured as previously described [12]. Briefly, FRC cells were grown in 48-well plates in as described above. Cells were treated with as described in individual figure legends. Total cellular AP activity was measured using a commercial assay kit (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). Protein was measured according to the method of Bradford using bovine serum albumin as a standard. AP activity was expressed as nanomoles of p-nitrophenol liberated per microgram of total cellular protein. For AP protein staining, FRC cultures were stained using a commercial kit (Sigma). Images of stained cells were captured with a CCD camera.

Formation of mineralized bone nodules and alizarin red S staining

Near confluent FRC cells in 12-well plates grown in αMEM containing 5% FBS, β-glycerol phosphate (5 mM) and ascorbic acid (100 μg/ml) were treated as indicated in the figure legend. Media were refreshed every 3 days. At the end of the experiment, cultures were stained with alizarin red S (AR-S) for mineralized bone nodules as previously described [12,13]. Briefly, cultures were rinsed with PBS, fixed with cold ethanol for 1 h, washed with water, stained with 40 mM Alizarin Red S for 10 min at room temperature, washed with water, and photographed using the CCD camera.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD. All data were analyzed using Student t-test in Microsoft Excel program. pitalic>0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Results

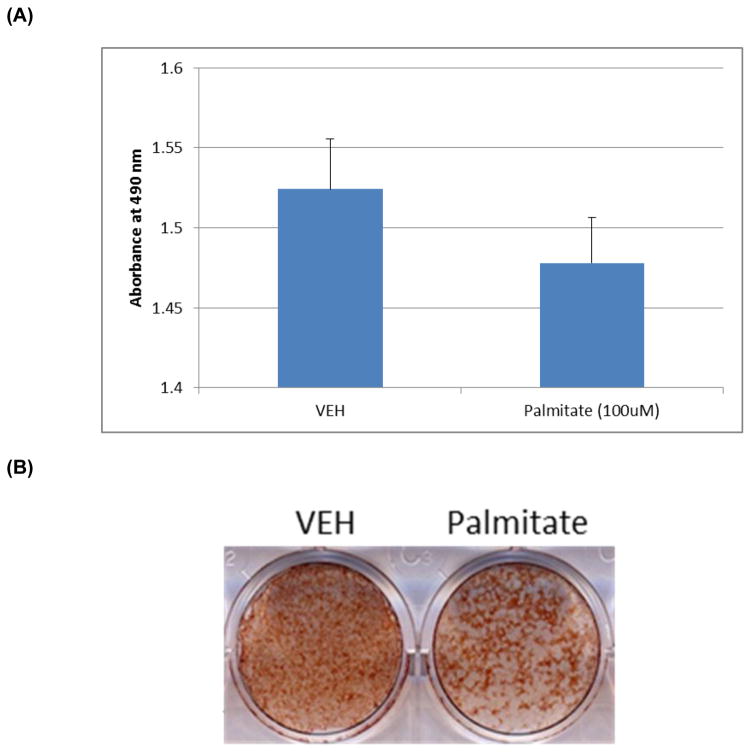

In order to evaluate the influence of lipid on osteoblast function, we incubated fetal rat calvarial (FRC) cells with palmitate, the primary product of de novo lipogenesis and a major component of triacylglycerol. We then evaluated effects of palmitate on FRC cell proliferation and osteogenic differentiation. As shown in Fig. 1A, palmitate did not inhibit cell proliferation to a significant extent but inhibited mineralized bone nodule formation in FRC cultures as revealed by Alizarin Staining (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. Effect of Palmitate on FRC cell proliferation and differentiation.

Fetal rat calvarial (FRC) cells were cultured under osteogenic conditions until 60% confluence, followed by addition of VEH (DMSO) and palmitate (100μM). (A) Cultures were terminated 48 hours after initiation treatment. Cell proliferation was measured using the commercial kit as described in Methods. (B) Cultures were treated for 14 days and stained with Alizarin Red for mineralized bone nodule formation as described in Methods.

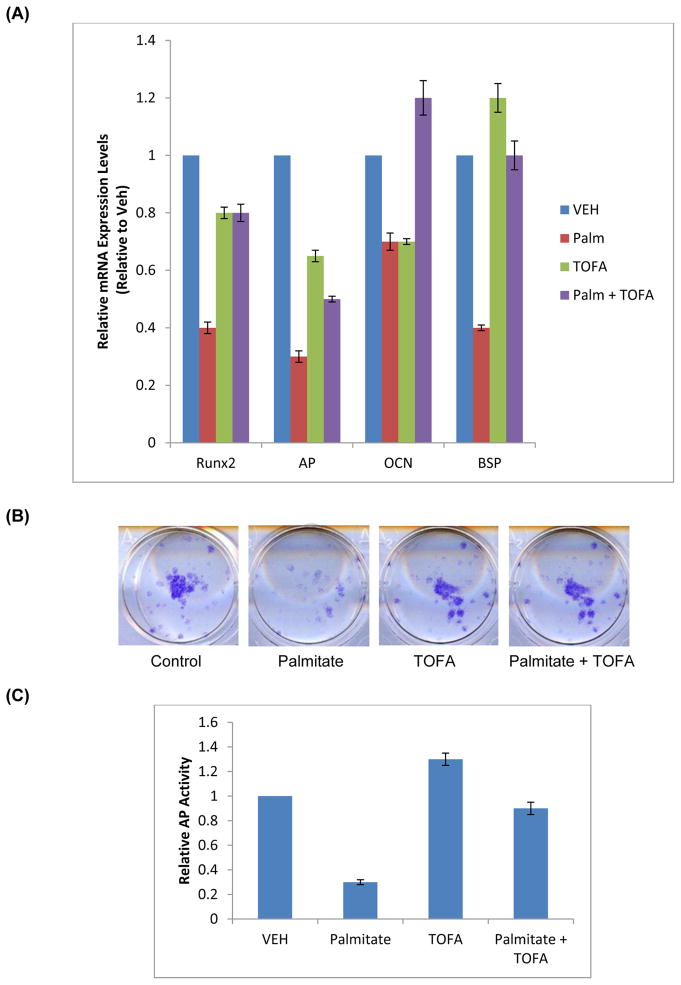

To determine the mechanisms by which palmitate affected osteoblast differentiation, we measured the mRNA levels of osteogenic markers in FRC cells incubated with palmitate. We also utilized an ACC inhibitor, TOFA, to further evaluate whether manipulation of fatty acid metabolism could modulate the effects of palmitate on FRC cells. Palmitate treatment of FRC cultures resulted in attenuation of mRNA expression of the osteoblast-specific transcription factor Runx2 and osteoblast differentiation markers, alkaline phosphatase (AP), Osteocalcin (OCN), and Bone Sialoprotein (BSP) by 60, 73, 30, and 59%, respectively, compared to the vehicle-treated control (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2. Effect of Palmitate and TOFA on osteogenic marker mRNA expression and alkaline phosphatase activity in FRC cells.

Fetal Rat Calvaria (FRC) cells were differentiated under osteogenic conditions until 60% confluence, followed by addition of VEH (DMSO), TOFA (1 μM), Palmitate (100 μM), or TOFA (1 μM) and Palmitate (100μM). Cultures were terminated 48 hours after initiation of treatment. (A)Total RNA was isolated and the steady-state mRNA expression levels of osteogenic markers, Runx2, alkaline phosphatase, osteocalcin, and bone sialoprotein were determined by real-time PCR. All data was calculated using the ΔΔCT method and compared to endogenous expression of β-2 Microglobulin. (*p≤0.01). (B) Cultures were stained for alkaline phosphatase using the commercial kit. (C) Enzymatic activity was measured in the cell lysates as described in Methods.

Effects of the ACC inhibitor TOFA alone on the expression of several osteogenic markers are shown in Fig. 2. TOFA (1 μM) alone inhibited mRNA expression of Runx2, OCN, and AP by 20, 33, and 34%, respectively, compared to the solvent-treated controls. At this TOFA concentration, BSP mRNA expression was not affected. TOFA was able to either partially or completely prevent the inhibitory effect of palmitate on the mRNA expression of these osteogenic markers (Fig. 2A). In particular, TOFA rescued partially the inhibition of palmitate on mRNA expression of Runx2 and AP and completely that of OCN and BSP in FRC cultures.

To further assess the effect of palmitate and TOFA on osteogenic differentiation, we evaluated their effects on the protein level and enzymatic activity of alkaline phosphatase. As seen in Fig. 2B and 2C, palmitate strongly inhibited AP activity, and AP protein levels. By comparison, TOFA alone showed little effect on AP activity or AP protein and was able to largely prevent the inhibition by palmitate.

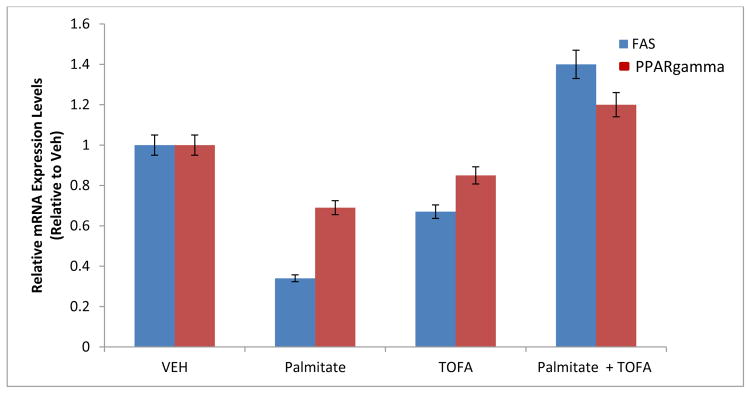

We also evaluated the effects of palmitate and TOFA on lipogenic gene expression in FRC cells. Fig. 3 shows that palmitate inhibited mRNA expression of two key enzymes in lipogenesis, fatty acid synthase (FAS) and the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ). Palmitate had a strong inhibitory effect on FAS mRNA expression and a lesser inhibitory effect on PPARγ mRNA (by 66% and 31%, respectively compared to the control). However, 1 μM TOFA was able to prevent these inhibitory effects.

Fig. 3. Effect of Palmitate and TOFA on FAS and PPARγ mRNA expression in FRC.

FRC cultures were treated as described in the legend of Fig. 2. Total RNA was isolated and the steady-state mRNA expression levels of lipogenic markers, FAS and PPARγ were determined by real-time PCR. All data was calculated using the ΔΔCT method and compared to endogenous expression of β-2 Microglobulin. (*p≤0.01).

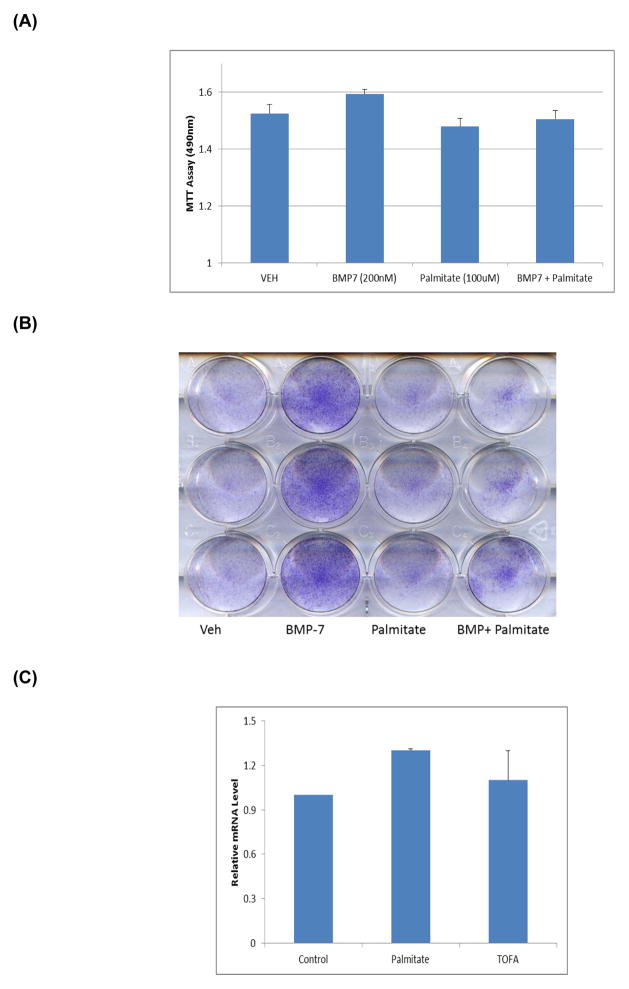

The results presented thus far focused on FRC cultures without added exogenous growth factors; however, we and others previously showed that BMP-7 stimulates FRC cell differentiation [14–16]. In the present study, we also evaluated effects of palmitate on BMP-7-stimulated FRC cell differentiation. Fig. 4A shows that neither BMP-7 alone nor palmitate alone affected FRC cell proliferation. The combination of BMP-7 and palmitate also did not affect cell proliferation. However, BMP-7 alone stimulated osteoblastic differentiation as indicated by an increase in AP activity; palmitate alone inhibited AP activity (Fig 4B). More importantly, BMP-7 was able to partially reverse the inhibitory action of palmitate (Fig 4B). Furthermore, palmitate did not inhibit endogenous BMP-7 mRNA expression in FRC cultures (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4. Effect of palmitate on BMP-7-treated FRC cultures.

(A) Cultures were terminated 48 hours after initiation of treatment with vehicle (VEH) or at the indicated concentrations of BMP-7 and/or palmitate. Cell proliferation was measured using the commercial kit as described in Methods. (B) Fetal Rat Calvarial (FRC) cells were treated with VEH (DMSO), Palmitate (100μM) alone, BMP-7 (100 ng/ml) alone or BMP-7 + palmitate (100 μM) for 14 days. At the end of the experiment, cultures were stained for alkaline phosphatase. (C) Total RNA was isolated and BMP-7 mRNA levels were determined by real-time PCR. All data was calculated using the ΔΔCT method and compared to endogenous expression of β-2 Microglobulin. (*p≤0.01).

Discussion

Several published studies have modeled the effect of fatty acids released from adipocytes in the bone marrow environment on osteoblast function in endochondral bone formation [6,17,18]. Our previously published [10] and current studies examined the effect of palmitate on calvarial cells, which are involved in intramembranous bone formation. Our results show that palmitate does not affect osteoblast cell proliferation but inhibits the osteogenic differentiation function of fetal rat calvarial cells. These results are similar to those previously reported for the effects of palmitate on human osteoblast differentiation [4]. In that study, osteoblasts were derived from long bone from young male adults. Long bones are formed via the endochondral ossification pathway. In that study, palmitate interfered with the transcriptional activity of Runx2 as well as the activity of SMAD transcription factors which mediate BMP-induced osteogenesis. Our published study [10] on fetal rat calvarial cells showed that palmitate reduced mRNA expression of two genes (Runx2 and OCN) that participate in osteoblastic cell differentiation. Our current study not only confirmed our published results but further showed that palmitate also reduced mRNA expression of genes (AP and BSP) that are responsible for mineralized bone nodule formation and thus osteoblast function. Taken together, these results showed that palmitate inhibited osteoblastic cell differentiation in both intramembranous and endochondral ossification. Furthermore, our observations that palmitate inhibited BMP-7-induced osteoblastic cell alkaline phosphatase activity suggest that palmitate inhibited not only spontaneous osteoblastic cell differentiation, but also growth factor (such as BMP-7)-induced osteoblast differentiation.

Our results provide insight into the mechanism by which palmitate inhibits intramembranous bone formation. TOFA is known to inhibit acetyl CoA carboxylase thereby reducing its product malonyl CoA levels. This will in turn result in decreased inhibition of carnitine palmitoyl CoA transferase 1, which is the rate limiting step in fatty acid beta oxidation [19]. At the TOFA concentrations we used, fatty acid oxidation is predicted to be increased [20]. Thus, our results showing that TOFA can prevent the inhibitory effects of palmitate strongly suggest that accumulation of fatty acids underlies the inhibitory effects of palmitate on osteogenic differentiation. Incomplete oxidation of fatty acids has been suggested to increase the accrual of lipid intermediates such as ceramides, fatty acyl CoAs, and diacylglycerol [1]. On the other hand, by promoting palmitate oxidation, TOFA may reduce the accumulation of these intermediates. Thus our results support a model in which promotion of fatty acid oxidation leads to clearance of precursors to these toxic lipid intermediates.

Our data also showed that palmitate reduced the expression of fatty acid synthase and PPARγ. The literature on the role of PPARγ on bone appears to be controversial. For examples, Akune et al. [21] showed that PPARγ enhances osteogenesis. Yu et al [22] showed that suppression of PPARγ resulted in inhibition of adipogenesis but did not promote osteogenesis of human bone marrow cells. In contrast, Duque et al. [23] showed that treatment with the PPARγ antagonist, bisphenol-A-diglycidyl ether (BADGE), increased bone mass in mice, consistent with PPARγ exerting an inhibitory effect on bone. Our previously published studies and our current findings are significant because they show that fatty acids can exert inhibitory effect on intramembranous bone formation. A previously published study showed that a PPARγ agonist promoted adipogenesis in FRC cells without inhibiting osteogenesis, in contrast to what was observed in bone marrow cells [8]. Our results thus suggest that there may exist an inverse relationship between osteogenesis and lipid levels in intramembranous bone such as is well documented for endochondral bone. FRC cells respond similarly to liver and adipose tissue in which exogenous fatty acids inhibit fatty acid synthase [24]. However, clearance of the palmitate inhibitory effect by using TOFA to promote fatty acid oxidation resulted in loss of the inhibitory effect on lipogenesis. Prior studies have shown that inhibition of adipocyte lipogenesis utilizing a fatty acid synthase inhibitor prevents the toxic effects of adipocytes on osteogenic differentiation in co-cultures of adipocytes and osteoblasts [6]. Our results provide novel insight suggesting that the manipulation of fatty acid oxidation by the osteoblasts themselves, specifically promotion of fatty acid oxidation, can relieve the inhibitory effects of fatty acids on osteogenic differentiation. Our current results could have strong implications for therapeutic approaches to combating age-related osteoporosis, which is thought to be largely due to dysregulated lipid metabolism.

Highlights.

Palmitate inhibits osteoblast differentiation

Fatty acid synthase

PPARγ

Acetyl Co-A carboxylase inhibitor TOFA

Fetal rat calvarial cell culture

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by NIA/NIH grant R21AG040612.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Schaeffer J. Lipotoxicity: When cells overeat. Curr Op Lipidology. 2003;14:281–287. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200306000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duque G. Bone and fat connection in aging bone. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20:429–434. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283025e9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sepe A, Tchkonia T, Thomou T, Zamboni M, Kirkland JL. Aging and regional differences in fat cell progenitors - a mini-review. Gerontology. 2011;57:66–75. doi: 10.1159/000279755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunaratnam K, Vidal C, Boadle R, Thekkedam C, Duque G. Mechanisms of palmitate-induced cell death in human osteoblasts. Biol Open. 2013;15:1382–1389. doi: 10.1242/bio.20136700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gunaratnam K, Vidal C, Gimble JM, Duque G. Mechanisms of palmitate-induced lipotoxicity in human osteoblasts. Endocrinology. 2014;155:108–116. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elbaz A, Wu X, Rivas D, Gimble JM, Duque G. Inhibition of fatty acid biosynthesis prevents adipocyte lipotoxicity on human osteoblasts in vitro. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:982–991. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00751.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong X, Bi L, He S, Meng G, Wei B, Jia BS, Liu J. FFAs-ROS-ERK/P38 pathway plays a key role in adipocyte lipotoxicity on osteoblasts in co-culture. Biochimie. 2014 Jan 11; doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2014.01.002. pii: S0300-9084(14)00006-6. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasagawa T, Oizumi K, Yoshiko Y, Tanne K, Maeda N, et al. The PPARγ-selective ligand BRL-49653 differentially regulates the fate choices of rat calvaria versus rat bone marrow stromal cell populations. BMC Dev Biol. 2008;8:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster DW. Malonyl-CoA: the regulator of fatty acid synthesis and oxidation. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1958–1959. doi: 10.1172/JCI63967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeh LCC, Ma X, Ford JJ, Adamo ML, Lee JC. Rapamycin Inhibits BMP-7-induced Osteogenic and Lipogenic Marker Expressions in Fetal Rat Calvarial Cells. J Cell Biochem. 2013;114:1760–1771. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeh LCC, Adamo ML, Kitten AM, Olson MS, Lee JC. Osteogenic protein-1-mediated insulin-like growth factor gene expression in primary cultures of rat osteoblastic cells. Endocrinology. 1996;137:1921–1931. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.5.8612532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeh LCC, Ma X, Matheny RW, Adamo ML, Lee JC. Protein kinase D mediates the synergistic effects of BMP-7 and IGF-I on osteoblastic cell differentiation. Growth Factors. 2010;28:318–328. doi: 10.3109/08977191003766874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stanford CM, Jacobson PA, Eanes ED, Lembke LA, Midura RJ. Rapidly forming apatitic mineral in an osteoblastic cell line (UMR 106-01 BSP) J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9420–9428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeh L-CC, Adamo ML, Olson MS, Lee JC. Osteogenic protein-1 and insulin-like growth factor I synergistically stimulate rat osteoblastic cell differentiation and proliferation. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4181–4190. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.10.5465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asahina I, Sampath TK, Nishimura I, Hauschka PV. Human osteogenic protein-1 induces both chondroblastic and osteoblastic differentiation of osteoprogenitor cells derived from newborn rat calvaria. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:921–933. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.4.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li IWS, Cheifetz S, McCulloch CAG, Sampath TK, Sodek J. Effects of osteogenic protein-1 (OP-1, BMP-7) on bone matrix protein expression by fetal rat calvarial cells are differentiation state specific. J Cell Physiol. 1996;169:115–125. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199610)169:1<115::AID-JCP12>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maurin AC, Chavassieux PM, Frappart L, Delmas PD, Serre CM, Meunier PJ. Influence of mature adipocytes on osteoblast proliferation in human primary co-cultures. Bone. 2000;26:485–489. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(00)00252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang D, Haile A, Jones LC. Dexamethasone-induced lipolysis increases the adverse effect of adipocytes on osteoblasts using cells derived from human mesenchymal stem cells. Bone. 2013;53:520–530. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukuda N, Ontko JA. Interactions between fatty acid synthesis, oxidation, and esterification in the production of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins by the liver. J Lipid Res. 1984;25:831–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otto DA, Chatzidakis C, Kasziba E, Cook GA. Reciprocal effects of 5-(tetradecyloxy)-2-furoic acid on fatty acid oxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 19851;242:23–31. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90475-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akune T, Ohba S, Kamekura S, Yamaguchi M, Chung UI, Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Harada Y, Azuma Y, Nakamura K, Kadowaki T, Kawaguchi H. PPARgamma enhances osteogenesis through osteoblast formation from bone marrow progenitors. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:846–855. doi: 10.1172/JCI19900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu WH, Li FG, Chen XY, Li JT, Wu YH, Huang LH, Wang Z, Li P, Wang T, Lahn BT, Xiang AP. PPARg suppression inhibits adipogenesis but does not promote osteogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44:377–384. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duque G, Li W, Vidal C, Bermeo S, Rivas D, Henderson J. Pharmacological Inhibition of PPARg Increases Osteoblastogenesis and Bone Mass in Male C57BL/6 Mice. J Bone and Miner Res. 2013;28:639–648. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Funai K, Song H, Yin L, Lodhi IJ, Wei X, Yoshino J, Coleman T, Semenkovich CF. Muscle lipogenesis balances insulin sensitivity and strength through calcium signaling. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1229–1240. doi: 10.1172/JCI65726. Erratum in J Clin Invest 123, 2013, 3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]