Abstract

Objective

To examine the association of IgG galactosylation aberrancy with disease parameters in rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods

N-glycan analysis of serum from multiple cohorts was performed. IgG N-glycan content and timing of N-glycan aberrancy relative to disease onset was compared in healthy and RA subjects. Correlations between aberrant galactosylation and disease activity were assessed in the RA cohorts. The impact of disease activity, gender, age, anti-CCP titer, disease duration, and CRP on aberrant galactosylation was determined using multivariate analysis. N-glycan content was also compared between epitope affinity purified autoantibodies and the remaining repertoire IgG in RA subjects.

Results

Our results confirm the aberrant galactosylation of IgG in RA (1.36 ± 0.43) compared to healthy controls (1.01 ± 0.23) (P < 0.0001). We observe a significant correlation between levels of aberrant IgG galactosylation and disease activity (Spearman rho = 0.37, p<0.0001). This correlation is higher in females [Spearman rho = 0.60 (P<0.0001)] than males [Spearman rho = 0.16 (P = 0.10)]. Further, IgG galactosylation aberrancy substantially predates onset of arthritis and the diagnosis of RA (3.5 years) and resides selectively in the anti-citrullinated peptide autoantibody fraction.

Conclusions

Our findings identify aberrant IgG galactosylation as a dysregulated component of the humoral immune response in RA that begins prior to disease onset, that associates with disease activity in a gender specific manner, and that resides preferentially in autoantibodies.

Keywords: IgG Glycosylation, Gender Differences, Dysregulation, Humoral Immunity, Disease Onset, Autoantibody

Introduction

Increasing experimental evidence implicates the humoral component of the adaptive immune system (i.e. secreted immunoglobulin) in the pathogenesis of RA. In addition to selective antibody reactivity to cyclic citrullinated peptides (1), a growing list of autoantibodies to citrullinated antigens are associated with RA [reviewed in (2)], including serologic reactivity to keratin [anti-keratin antibodies (AKA)] (3), BiP (4, 5), RA33 (6, 7), anti-perinuclear factor (APF or anti-fillagrin) (8), anti-collagen (9–11), anti-vimentin (also called Sa) (12–16), fibrinogen (17–20), and others (21). In addition, the frequent presence of serum rheumatoid factor (RF) and synovial fluid immune complexes in patients with RA also points to dysregulation of the humoral immune response (22, 23).

Aberrant glycosylation of IgG comprises a less well-understood abnormality of humoral immunity in patients with RA (24). Secreted IgG exists as a glycosylated dimer of heavy- and light-chain monomers. The glycosylation of IgG is highly regulated and limited. There are only two conserved N-linked glycosylation sites on IgG. One of the N-glycans is present invariably at the asparagine 297 (Asn-297) residue in the heavy-chain CH2 domain (Fc portion). The other N-glycan is attached to the hypervariable region of the Fab arm in the minority (~20%) of circulating IgG and is heavily sialylated (25). The Asn-297 glycan is a complex biantennary structure whose core consists of 2 α-mannosyl residues attached to a β-mannosyl-di-N-acetylchitobiose unit. To this core structure, N-acetylglucosamine and galactose moieties are subsequently added via transferase enzymes to form the mature glycoform. However, the composition of the arms of the IgG Asn-297 glycoform is not homogeneous in vivo and varies depending on the degree of processing by terminal glycosyltransferases.

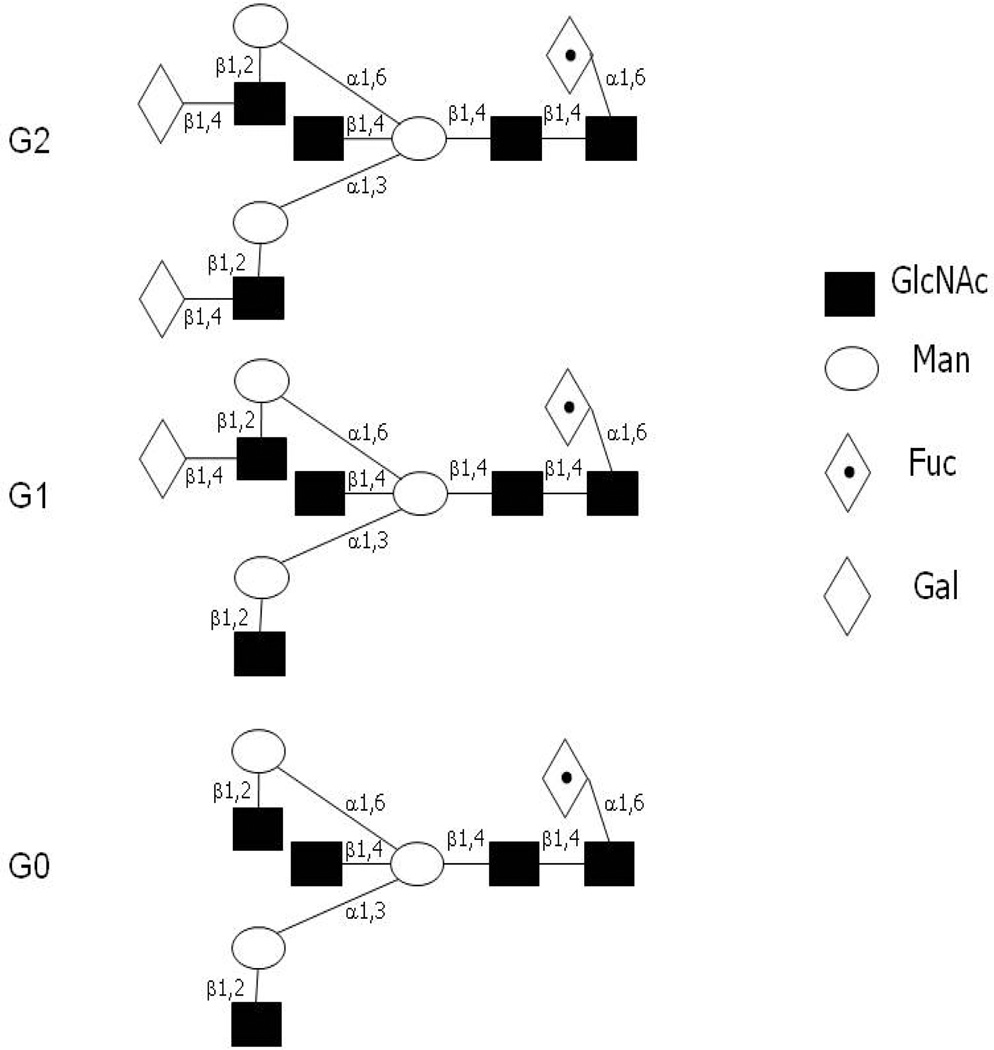

Decreased IgG Asn-297 oligosaccharide galactosylation (truncation of terminal galactose residues) is observed in patients with RA and juvenile chronic arthritis (24, 26–29), a finding not correlated with other forms of inflammatory or infectious arthritis or other rheumatic conditions (26, 28). Since there are two arms that can be galactosylated on the IgG oligosaccharide, this decreased galactosylation consists of either no terminal galactose (G0), or a terminal galactose present only on one arm (G1) (Figure 1). Previous analyses have shown that RA is associated with increased IgG G0 glycoform (no terminal galactose) and not the IgG G1 or G2 glycoforms (24). Interestingly, in a small series of subjects (N=7) this hypogalactosylation reverses with pregnancy and reverts post-partum, a fluctuation that correlates with improvements and worsening of disease (30, 31).

Figure 1. Oligosaccharide structures attached to Asp-297 of IgG.

Shown are fully galactosylated (G2, FA2BG2), monogalactosylated (G1, FA2[6]BG1) and agalactosylated (G0, FA2B) form of the biantennary oligosaccharide attached to the CH2 Fc region of IgG (67). In this nomenclature, since all N-glycans have two core GlcNAc residues, a F at the start of the abbreviation indicates a core fucose in α1-6 linkage to the inner GlcNAc. A2 denotes a biantennary structure with both GlcNAcs β1-2 linked. B symbolizes a bisecting GlcNAc linked β1-4 to β1-3 mannose. Gx communicates the number of β1-4 linked galactose residues on each antenna. Here, [6]G1 indicates that the galactose is on the antenna of the α1-3 or α1-6 mannose.

From a functional standpoint, structural studies have demonstrated that the post-translationally attached oliogosaccharides provide structural integrity to the IgG molecule [reviewed in (32)]. Crystal structures reveal that the oligosaccharide present in the CH2 Fc region is sequestered within space internal to the protein structure (32–35). This contrasts with many glycoforms that tend to surround or ‘coat’ the protein surface. A functional role for the oligosaccharide in the IgG Fc CH2 domain has been demonstrated in activation of complement, in interaction with the Fc receptor, and in antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) (32, 36–41) all of which are perturbed by truncation of the Asn-297 oligosaccharide. In vitro, rheumatoid factors preferentially bind hypogalactosylated IgG (42), and hypogalactosylated IgG demonstrates increased potential for interaction with the complement pathway via mannose-binding protein (43). These observations provide potential mechanisms for participation of hypogalactosylated IgG in RA pathogenesis.

The major factors hindering the extensive examination of the IgG glycan aberrancy in RA have included the lack of sensitive, accurate methods for quantifying IgG glycoforms and access to biospecimens from highly characterized cohorts of subjects with RA. Recent development of a novel high-throughput method for IgG glycan quantification (44) and access to an extensive collection of RA subjects via multiple cohorts enabled us to examine further this aspect of humoral dysregulation and its association with disease status in RA. Herein, we show that IgG glycan aberrancy substantially predates disease onset and appears shortly after development of anti-CCP antibodies. Further, aberrant IgG glycan levels correlate significantly with disease activity. Examination of an autoantibody fraction demonstrates enrichment of aberrantly galactosylated IgG relative to repertoire IgG. Taken together, these data point to IgG glycosylation as a pathway subject to autoimmune dysregulation in RA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study populations

IgG N-glycan quantification was performed on subjects with RA obtained from two cohorts: BRASS and DoDSR.

BRASS (Brigham Rheumatoid Arthritis Sequential Study)

The BRASS is a prospective observational study of 1100 RA patients receiving care at the Brigham & Women’s Hospital that combines extensive clinical information and associated serum specimens (45, 46). 232 sequential subjects selected to balance male and female composition were utilized for this study. Sera from gender-matched anonymous healthy blood donors were used as controls for the BRASS-focused studies. These cohorts are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the BRASS and control cohorts

| BRASS cohort (n = 232) | Control cohort (n = 232) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 57.9 ±14.1 | 52.6 ± 14.1 |

| Disease duration, years | 15.1 ± 13.0 | N/A |

| Female (%) | 119 (51.3) | 119 (51.3) |

| sG0/G1 ratio (±SD) | 1.36 (± 0.43) | 1.01 ± 0.23 |

| DAS28-CRP3 (±SD) | 4.15 (± 1.74) | N/A |

| RF-positive (%) | 138 (58.9) | N/A |

| Anti-CCP titer positive (%) | 152 (64.6) | N/A |

Department of Defense Serum Repository (DoDSR) Cohort

Eighty-three cases with RA were identified through the Walter Reed Army Medical Center (WRAMC) Rheumatology Clinic. These cases had stored pre- and post-RA diagnosis serum samples available for testing for IgG glycosylation through the DoDSR, a serum bank housing samples from military personnel collected at several time points during their military career including induction into the military, at deployment, and every 1–2 years during military service (47). For comparative analyses, control serum samples were selected from the DoDSR matched to case samples by age, race, gender, region of military deployment, and duration of sample storage. Details of this cohort are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the DoDSR and control cohorts

| Military RA Cases (N = 83) |

Military Controls (N = 83) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mean Age at RA diagnosis (±SD) | 39.9 (±10.0) | N/A |

| Percent female (%) | 38 | 38 |

| Total number of samples | 290 | 290 |

| Pre-RA diagnosis samples | 243 | N/A |

| Mean number of pre-RA diagnosis samples per case | 2.9 ±1.2 | N/A |

| Time range of samples pre- and post-RA diagnosis | 13.7 years pre-RA to 11.7 years post-RA | N/A |

| Mean duration ( in years) of samples pre- RA diagnosis (± SD) | 6.6 (±3.7) | N/A |

| Mean sG0/G1 ratio (±SD) | 0.97 (± 0.24) | 0.90 (± 0.16) |

| Median time of joint symptom onset prior to diagnosis | 0.5 years | N/A |

| RF-positive pre-RA diagnosis | 47 (57%) | N/A |

| Anti-CCP positive pre-RA diagnosis | 51 (61%) | N/A |

All studies were performed under Institutional Review Board approved protocols.

Preparation of an anti-citrulline antibody pool

Patients

Serum samples were collected with informed consent from 8 patients from the Rheumatology Clinic, London, Ontario, Canada, all of whom fulfilled the 1987 American College of Rheumatology classification for RA (48). All of the patients were positive for anti-CCP antibodies as measured by the Euroimmun ELISA kit (EUROIMMUN AG Lübeck) and IgG. All patients also demonstrated high titer antibodies to the synthetic citrullinated peptide JED in ELISA assay (49). The JED ELISA was carried out as previously described by us for other antigens (4). A positive cut-off value for JED was 3.5 AU/ml. IgG anti-JED antibody quantity was expressed as arbitrary units (AU/ml) that were determined using a reference RA serum(50) These studies were approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the University of Western Ontario, Canada.

JED peptide

Several years ago, Hill et al developed a proprietary citrullinated peptide (JED) which was originally designed to bind to DRB1*0401 with high affinity in its linear form (49, 51, 52). The cyclic form of this peptide (used in this study) was recognized by the majority of anti-CCP2 positive RA sera by standard ELISA and was similarly specific for RA as CCP2 (49). The JED peptide contains 18 amino acids nine of which are citrullines and two of which are cysteines that allow disulfide bond mediated cyclization. The carboxy-terminus of JED peptide is amidated.

Antibody fractionation

Anti-JED antibody was epitope affinity purified on a HiTrap™ NHS-activated HP Sepharose (GE Healthcare) coupled with JED peptide as per the manufacturer’s instructions. JED was synthesized by the Advanced Protein Technology Centre, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada.

Briefly, sera diluted five-fold in 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH.7.0 were passed through a JED affinity column. Bound anti-citrullinated JED peptide antibodies were eluted with an elution buffer of 10 mM sodium phosphate containing 2.5 M magnesium chloride, pH 7.3. The eluted anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies were desalted into PBS using a PD-10 Sephadex™ G-25 column (GE Healthcare) as per manufacturer’s instructions. Complete removal of anti-JED reactive antibodies in flow through material was examined via ELISA as described above (49).

Repertoire IgG purification

Flow through fractions depleted of anti-citrullinated peptide antibody collected from the JED affinity column were passed through a HiTrap™ Protein G HP column (GE Healthcare) to purify the IgG repertoire lacking anti-citrullinated peptide reactivity. The IgG elution and desalting was performed as described above.

Release, labeling and quantification of N-glycans from serum samples

IgG N-glycan analysis was performed as previously described (44). Briefly, serum samples (5 µl) were reduced, alkylated, and immobilized in SDS-polyacrylamide gel matrix in 96 well format. Samples were subsequently treated with PNGase F (Prozyme, San Leandro, CA) to release N-glycans which were then labeled with 2-aminobenzamide (2-AB) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Prozyme, San Leandro, CA). Labeled N-glycans were quantified via HPLC using a normal phase TSK gel amide-80 column (4.6 mm (ID) × 25.0 cm (L)) (44) and an ammonium formate:acetonitrile gradient (20 mM ammonium formate (35%-->47%)(Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA);acetonitrile (65%-->53%) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) over 60 minutes). G0 and G1 peaks were selected based on previous studies definitively identifying the retention times of these structures (via glycosidase digestion or mass spectrometry) relative to a 2-AB labeled Glucose Homopolymer (GHP) ladder (Associates of Cape Code Inc. East Falmouth, MA). sG0/G1 values were derived by dividing the percent area of G0 (FA2 and FA2B) with G1 (FA2[6]G1, FA2[6]BG1 and FA2[3]G1) (see Figure 1 legend for details).

Statistical analyses

The presence or absence of statistical differences between controls and cases was evaluated using Student’s T-test. The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test which indicated that distribution of disease-related parameters among subjects in the BRASS cohort was not normally distributed. Therefore, univariate correlation analyses between sG0/G1 and RA disease-related parameters were determined using the Spearman’s rank coefficient (Spearman’s rho). Gender specific data in BRASS was examined using ANOVA. Multivariate analysis was performed to determine the impact of age on sG0/G1 as a possible confounder in the correlation of DAS with sG0/G1 adjusting for gender.

Analyses for the point of separation over time for the sG0/G1 ratio between RA cases and their controls in the military cohort was performed using a random effects mixed model with random subject terms for intercept and slope. The population mean regression values were compared at incremented times ranging from ~13 years prior and ~11 years post diagnosis using a Student T distribution test statistic. To control for multiple comparisons a Sheffe adjusted critical value of 2.44 was used, above which a significant difference in the sG0/G1 ratio was declared.

All analyses were performed using SAS 9.1.

Results

RA patients display aberrant serum IgG glycan content

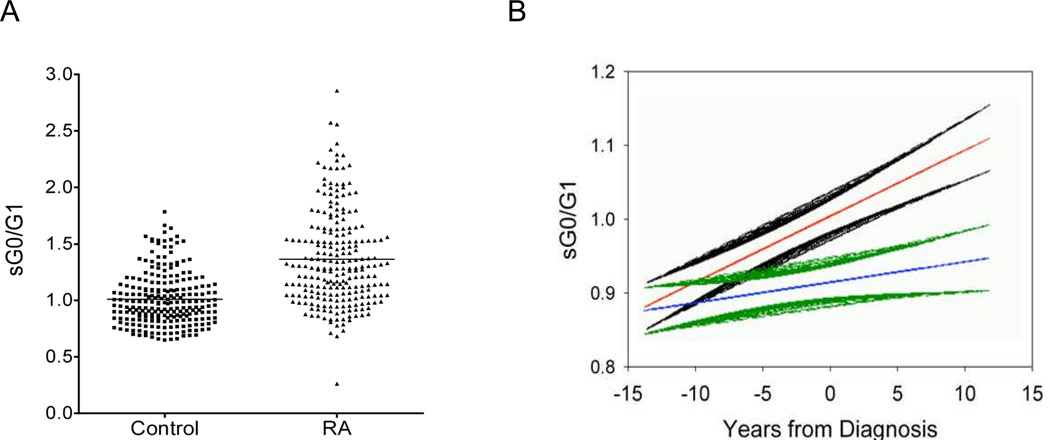

Previous studies with purified IgG document the abnormal IgG glycan profile in patients with RA and not in numerous other autoimmune diseases (26, 53). In our initial studies, we confirmed the aberrant IgG glycan profile in 232 RA subjects participating in the BRASS cohort relative to 232 healthy blood donors using a recently developed in-gel digest high throughput HPLC-based method to quantify IgG G0 and G1 glycoforms in serum samples (sG0/G1) (Figure 2A). Previous studies demonstrated a high correlation between measurement of G0/G1 glycoform ratio in whole serum and the glycoform content of affinity purified IgG (44). To confirm that G0 and G1 glycoforms comprise the majority of IgG glycoforms measured in whole serum with our assay, we examined G0 and G1 levels in sera after depletion of IgG and found that over 70% ± 5% of the G0 and 89% ± 8% of the G1 glycoform in serum originates from IgG (Supplementary figure 1). Because our glycan profiles are obtained from unfractionated serum, our results will be referred to as serum hypogalactosylation analysis (sG0/G1). We interpret these findings as synonymous with IgG glycoform quantification.

Figure 2. IgG galactosylation (sG0/G1) ratios are aberrant in RA and this aberrancy precedes disease onset.

A, sG0/G1 ratios for RA subjects (N = 232) and gender-matched controls (N = 232) were determined using the in-gel digest assay on whole serum (44). Individual values as well as averages for RA subjects and healthy donors are shown. (P < 0.0001). B, sG0/G1 ratios were determined in a longitudinal series of healthy and pre- and post-disease onset serum samples in the DoDSR cohort. Shown are mean and SEM values for subjects with RA (red and black) and age- and gender-matched healthy controls (blue and green). Values are reported longitudinally relative to onset of disease in the RA cohort. Note the sG0/G1 ratios between healthy and disease subjects diverge significantly ~3.5 years prior to disease onset.

These analyses support previous studies and demonstrate a significant elevation in the sG0/G1 ratio in the serum samples of RA patients (Figure 2A). More specifically, the mean values ± SD of sG0/G1 ratios for control and BRASS subjects are 1.01 ± 0.23 and 1.36 ± 0.43, respectively (P<0.0001). The sG0/G1 ratio difference between RA patients and healthy controls remains significant after controlling for age and gender.

sG0/G1 correlation with disease activity in RA

The BRASS registry extensively documents parameters of disease activity in RA subjects (46). To explore a correlation between IgG glycoform content and disease activity, we compared sG0/G1 ratios with the DAS28-CRP3 (DAS) (54) measure of disease activity in the BRASS cohort. These analyses reveal a significant correlation between sG0/G1 and the DAS (Spearman rho = 0.376, P<0.0001) (Table 3). Examination of individual components that comprise the DAS measurement also show significant correlations indicating that the sG0/G1 correlation is not preferentially impacted by an isolated measure of the disease (Table 3).

Table 3.

Spearman correlations between the sG0/G1 ratio and disease activity parameters in the BRASS cohort

| DAS28- CRP3 |

CRP | Joints total | Swollen joints total |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman rho | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.25 |

| P-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| N | 229 | 229 | 232 | 232 |

Gender specific association between sG0/G1 and disease activity

We next examined for confounders that may impact the correlation between sG0/G1 and DAS in the BRASS cohort. Indeed, previous studies have shown an age-dependent increase in sG0/G1 (55–57). Here, in addition to age, we used a series of multivariate analyses to assess the impact of CCP, disease duration and gender on the sG0/G1:DAS correlation. With the exception of gender, we note no impact from these factors on the sG0/G1:DAS correlation.

Having identified a potential impact based on gender, and since RA displays a predilection for females, we further investigated the influence of gender on IgG glycoform content and their association with disease. When stratifying sG0/G1 values by gender, we observed a slightly higher mean value of sG0/G1 in males (1.44 ± 0.44) than females (1.30 ± 0.40) (P = 0.0132). Examination of the correlation between sG0/G1 and DAS demonstrated a high correlation in females (Spearman rho = 0.60, P<0.0001, N = 119) while males displayed no appreciable correlation between sG0/G1 with DAS (Spearman rho = 0.16, P = 0.10, N = 107).

Aberrant galactosylation of IgG substantially precedes disease onset in RA

For these studies, we utilized The Department of Defense Serum Repository (DoDSR) which contains serial serum specimens obtained up to 13.7 years prior to and 11.7 years after diagnosis of RA patients and age-, gender- and ethnicity-matched healthy controls (47). In this cohort, we observed that sG0/G1 ratios for RA patients and controls were similar at remote time points (more than a decade) prior to disease onset. Interestingly, aberrant sG0/G1 values became significant substantially prior to disease onset (3.5 years, see Figure 2B) in a time frame between the initial detection of anti-CCP or RF antibodies and onset of disease (47).

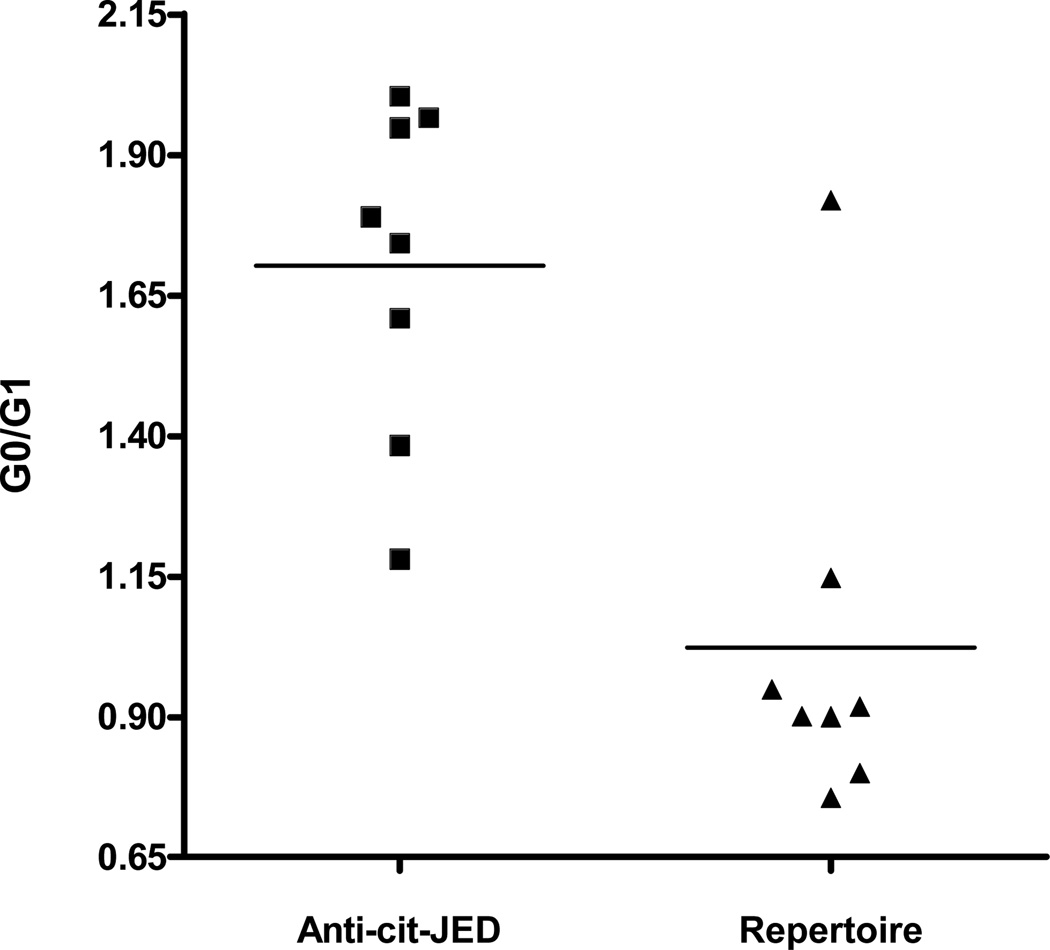

Selective aberrant galactosylation of autoantibodies in RA

The observation that both autoantibodies and IgG glycan aberrancy predate the onset of systemic inflammation led us to hypothesize that inappropriate IgG galactosylation may be present in IgG whose synthesis is driven by autoimmune stimulation. Our initial analyses examined for a correlation between IgG glycan content and anti-CCP or RF titer but indicated no significant correlations. Since the anti-CCP clinical assay is not thought to contain bona-fide autoantigens, to further explore the selectivity of IgG modification in autoantibodies in RA, we compared the glycoform content in an anti-citrulline reactive autoantibody fraction with that in repertoire IgG isolated from patients with RA. Here, we selected a subset of patients whose anti-CCP reactivity was quantitatively depleted by epitope-affinity removal of autoantibodies reactive to a HLA DR4 binding citrullinated peptide (JED) (49, 51, 52). In these patients, we are thus able to effectively fractionate the anti-citrulline reactive autoantibodies from the non-autoreactive IgG repertoire. Examination of these IgG fractions reveals selective hypogalactosylation of the autoantibody pool while repertoire antibodies maintain normal glycan content (Figure 3). In specific, we observe an enriched sG0/G1 ratio of 1.6 ± 0.3 in the autoantibody fraction whereas the repertoire IgG pool contains a ratio of 0.88 ± 0.07 (P<0.006) which is synonymous with the sG0/G1 ratio observed in healthy control subjects. Thus, IgG glycan aberrancy is selective for autoreactive anti-JED IgG in this cohort of subjects.

Figure 3. sG0/G1 ratios in anti-citrulline autoantibodies vs. repertoire IgG.

Shown are sG0/G1 ratios of IgG autoantobodies reactive to the citrullinated JED autoantigen and residual repertoire IgG after epitope affinity removal of anti-JED autoantibodies. Symbols portray individual subject values. Horizontal lines denote average values. (P=0.006).

Discussion

Our studies in large cohorts of subjects with RA both confirm previous studies documenting aberrant IgG glycan modification in disease (24, 26, 30, 53, 58) and provide new evidence regarding the timing of glycan aberrancy, the association of glycan levels with disease activity and the preferential glycan abnormality in disease associated autoantibodies. By examining aberrant glycosylation of IgG, our studies provide further evidence regarding dysregulated humoral immunity in RA. We find that this aspect of humoral dysregulation begins early—at least 3.5 years prior to onset of symptoms. The intriguing observation that fractionated anti-citrulline autoantibodies contain substantially more G0 glycoform than the non-autoreactive IgG repertoire fraction points to a selective modification of autoreactive antibody producing B-lineage populations in disease. The correlation of glycoform content and disease activity appears restricted to females with RA, raising the possibility of gender specific autoimmune disease mechanisms. Taken together with previous studies, our findings identify modulation of IgG glycan content as a facet of the humoral immune system impacted in the autoimmune pathophysiology of RA.

Recent studies have documented the appearance of disease-associated anti-CCP antibodies and RF several years prior to the onset of arthritis symptoms (47). These findings suggest that humoral immune dysregulation may substantially predate clinical manifestations of disease in RA. Hypothesizing that the humoral diathesis in RA includes the post-translational modification of IgG, we queried whether IgG glycan aberrancy also substantially predates the onset of the disease. Our findings suggest that the dysregulation of IgG glycosylation is among the pathways involved in the preclinical immunopathogenesis of RA.

The timing of IgG glycosylation aberrancy relative to the development of anti-citrullinated peptide epitope reactivity is intriguing. The intercurrent timeframe of the IgG glycan aberrancy between the emergence of anti-CCP antibodies and onset of disease implies distinct mechanisms driving IgG glycosylation. This observation also raises the possibility that change in IgG glycosylation status is among the preclinical events that contribute to disease initiation. However, we recognize that the development of IgG glycan aberrancy may proceed slowly and simply become statistically significant at 3.5 years prior to disease onset rather than signify a dichotomous event. Resolving these issues will require identification of the stimulus driving production of hypogalactosylated IgG as well as further understanding of the functional contribution of IgG glycosylation to disease physiology. We anticipate that examination of these mechanistic questions will provide new insight into disease pathways active prior to onset of symptoms.

In the context of established disease, the striking gender difference in correlation between IgG glycan content and disease activity raises the possibility of differential immune stimulation in male and female patients. To our knowledge, this is the first gender selective immunologic aspect identified in RA. Since average disease severity did not differ in the male and female RA subjects in the BRASS cohort, it is unlikely that this difference is exclusively attributable to feedback from general systemic inflammation. Indeed, this observation implies a hormonal influence on disease pathophysiology manifest in the post-translational modification of IgG. Since RA is a disease that displays a female predilection, further investigation of the role of sex hormones in regulating IgG glycosylation holds promise for providing further understanding into the female predominance of this disease.

The selectivity of IgG glycan aberrancy within a defined autoantibody fraction of serum IgG supports the hypothesis that antigen driven autoimmune mechanisms impact the posttranslational modification of these autoantibodies. The observation that repertoire IgG maintains a normal glycan profile in these RA patients further supports the contention that generalized systemic inflammation does not impart global changes in IgG glycosylation. This contention is congruent with previous studies demonstrating lack of hypogalactosylated IgG glycoforms in various other infectious or inflammatory conditions (26). The autoantibodies examined herein were selected based on our ability to quantitatively deplete anti-citrulline reactivity in the subset of subjects examined. Future studies examining other autoantibodies will define the extent of selectivity of IgG glycan dysregulation in other autoantibodies associated with RA. Assuming that our findings are not unique to the autoreactivity examined in our studies, we anticipate that elucidating the immunologic pathways regulating IgG glycan levels will identify immunopathologic mechanisms active in RA.

Although the lack of correlation between aberrant galactosylation of IgG and anti-CCP titer remains enigmatic, our findings are in agreement with numerous studies documenting lack of association between anti-CCP titer and defined autoantibody levels or clinical activity in RA (59–65). Indeed, this lack of correlation has led other investigators to conclude that their results indicate “the presence of other, non-measured autoantibodies that affect the risk for RA” in their studies examining the anti-CCP assay (66). It deserves mention that the peptide targets utilized in the commercial anti-CCP biomarker assays likely do not contain bona-fide autoantigens. Indeed, while measurement of ‘CCP’-reactive antibodies may be useful as biomarkers, these tests are not designed to measure true autoantibodies. Therefore, our observation that IgG glycan aberrancy resides in the autoantibody fraction of IgG is not inconsistent with results showing lack of association between IgG glycoform levels and CCP titers.

Finally, it is also interesting to note that disease duration did not affect IgG galactosylation status in the BRASS cohort, since sG0/G1 increases with age, and increases faster over time in pre-clinical RA in the DoDSR group. This observation raises the possibility that successful treatment of RA attenuates the tendency of sG0/G1 to rise over time. As noted above, whether this is due to decreased input from yet-undefined inflammatory signals, as suggested by the correlation between DAS and G0/G1, or from impact of therapeutics used in treatment of RA remains unresolved. Further examination of the immunopathology that drives aberrant IgG glycosylation in RA is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Dr. Lee’s work was supported by an ACR-REF Within our Reach grant.

Dr. Ercan is supported by a training grant from NIH (T32 AR07530-25)

Dr. Deane was supported by NIH grant K-23 AR051461

Dr. Holers’ work was supported by NIH grants R21 AI61479, T32 AR 07534, U-19 AI50864, and AR51394

Dr. Solomon was supported by a grant from NIH K24 AR 055989

Drs. Weinblatt, Shadick and Lee were supported by grants from Biogen/Idec and Crescendo Biosciences for work in the BRASS registry

Drs. Cairns and Bell’s work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant. Dr. Cairns is a recipient of an award from the Calder Foundation.

Thanks to William R. Gilliland, MD William R. Gilliland, M.D. COL, USA (ret) and Jess D. Edison, M.D. MAJ(P), MC, USA at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center for their assistance in the preparation of data obtained from military subjects for this manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: “The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government.”

REFERENCES

- 1.Schellekens GA, Visser H, de Jong BA, van den Hoogen FH, Hazes JM, Breedveld FC, et al. The diagnostic properties of rheumatoid arthritis antibodies recognizing a cyclic citrullinated peptide. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2000;43(1):155–163. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<155::AID-ANR20>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Boekel MA, Vossenaar ER, van den Hoogen FH, van Venrooij WJ. Autoantibody systems in rheumatoid arthritis: specificity, sensitivity and diagnostic value. Arthritis Res. 2002;4(2):87–93. doi: 10.1186/ar395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young BJ, Mallya RK, Leslie RD, Clark CJ, Hamblin TJ. Anti-keratin antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. Br Med J. 1979;2(6182):97–99. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6182.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blass S, Specker C, Lakomek HJ, Schneider EM, Schwochau M. Novel 68 kDa autoantigen detected by rheumatoid arthritis specific antibodies. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54(5):355–360. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.5.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corrigall VM, Bodman-Smith MD, Fife MS, Canas B, Myers LK, Wooley P, et al. The human endoplasmic reticulum molecular chaperone BiP is an autoantigen for rheumatoid arthritis and prevents the induction of experimental arthritis. J Immunol. 2001;166(3):1492–1498. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hassfeld W, Steiner G, Hartmuth K, Kolarz G, Scherak O, Graninger W, et al. Demonstration of a new antinuclear antibody (anti-RA33) that is highly specific for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1989;32(12):1515–1520. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780321204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steiner G, Hartmuth K, Skriner K, Maurer-Fogy I, Sinski A, Thalmann E, et al. Purification and partial sequencing of the nuclear autoantigen RA33 shows that it is indistinguishable from the A2 protein of the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein complex. J Clin Invest. 1992;90(3):1061–1066. doi: 10.1172/JCI115921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nienhuis LF, Mandema EA. A new serum factor in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The antiperinuclear factor. Annals of Rheumatic Disease. 1964;23:302–305. doi: 10.1136/ard.23.4.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andriopoulos NA, Mestecky J, Miller EJ, Bradley EL. Antibodies to native and denatured collagens in sera of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1976;19(3):613–617. doi: 10.1002/art.1780190314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uysal H, Bockermann R, Nandakumar KS, Sehnert B, Bajtner E, Engstrom A, et al. Structure and pathogenicity of antibodies specific for citrullinated collagen type II in experimental arthritis. J Exp Med. 2009;206(2):449–462. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wozniczko-Orlowska G, Milgrom F. Collagen-anti-collagen complexes in rheumatoid arthritis sera. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1982;68(1):28–34. doi: 10.1159/000233063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Despres N, Boire G, Lopez-Longo FJ, Menard HA. The Sa system: a novel antigen-antibody system specific for rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1994;21(6):1027–1033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayem G, Chazerain P, Combe B, Elias A, Haim T, Nicaise P, et al. Anti-Sa antibody is an accurate diagnostic and prognostic marker in adult rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(1):7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vossenaar ER, Despres N, Lapointe E, van der Heijden A, Lora M, Senshu T, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis specific anti-Sa antibodies target citrullinated vimentin. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6(2):R142–R150. doi: 10.1186/ar1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hueber W, Kidd BA, Tomooka BH, Lee BJ, Bruce B, Fries JF, et al. Antigen microarray profiling of autoantibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(9):2645–2655. doi: 10.1002/art.21269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verpoort KN, Cheung K, Ioan-Facsinay A, van der Helm-van Mil AH, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, et al. Fine specificity of the anti-citrullinated protein antibody response is influenced by the shared epitope alleles. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(12):3949–3952. doi: 10.1002/art.23127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masson-Bessiere C, Sebbag M, Girbal-Neuhauser E, Nogueira L, Vincent C, Senshu T, et al. The major synovial targets of the rheumatoid arthritis-specific antifilaggrin autoantibodies are deiminated forms of the alpha- and beta-chains of fibrin. J Immunol. 2001;166(6):4177–4184. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.4177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takizawa Y, Suzuki A, Sawada T, Ohsaka M, Inoue T, Yamada R, et al. Citrullinated fibrinogen detected as a soluble citrullinated autoantigen in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fluids. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(8):1013–1020. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.044743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuo K, Xiang Y, Nakamura H, Masuko K, Yudoh K, Noyori K, et al. Identification of novel citrullinated autoantigens of synovium in rheumatoid arthritis using a proteomic approach. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(6):R175. doi: 10.1186/ar2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skriner K, Adolph K, Jungblut PR, Burmester GR. Association of citrullinated proteins with synovial exosomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(12):3809–3814. doi: 10.1002/art.22276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hueber W, Tomooka BH, Batliwalla F, Li W, Monach PA, Tibshirani RJ, et al. Blood autoantibody and cytokine profiles predict response to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(3):R76. doi: 10.1186/ar2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schur PH, Britton MC, Franco AE, Corson JM, Sosman JL, Ruddy S. Rheumatoid synovitis: complement and immune complexes. Rheumatology. 1975;6:34–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruddy S, Britton MC, Schur PH, Austen KF. Complement components in synovial fluid: activation and fixation in seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1969;168(1):161–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1969.tb43105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parekh RB, Dwek RA, Sutton BJ, Fernandes DL, Leung A, Stanworth D, et al. Association of rheumatoid arthritis and primary osteoarthritis with changes in the glycosylation pattern of total serum IgG. Nature. 1985;316(6027):452–457. doi: 10.1038/316452a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holland M, Yagi H, Takahashi N, Kato K, Savage CO, Goodall DM, et al. Differential glycosylation of polyclonal IgG, IgG-Fc and IgG-Fab isolated from the sera of patients with ANCA-associated systemic vasculitis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1760(4):669–677. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parekh R, Isenberg D, Rook G, Roitt I, Dwek R, Rademacher T. A comparative analysis of disease-associated changes in the galactosylation of serum IgG. J Autoimmun. 1989;2(2):101–114. doi: 10.1016/0896-8411(89)90148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Zeben D, Rook GA, Hazes JM, Zwinderman AH, Zhang Y, Ghelani S, et al. Early agalactosylation of IgG is associated with a more progressive disease course in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results of a follow-up study. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33(1):36–43. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/33.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watson M, Rudd PM, Bland M, Dwek RA, Axford JS. Sugar printing rheumatic diseases: a potential method for disease differentiation using immunoglobulin G oligosaccharides. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1999;42(8):1682–1690. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199908)42:8<1682::AID-ANR17>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Axford JS, Mackenzie L, Lydyard PM, Hay FC, Isenberg DA, Roitt IM. Reduced B-cell galactosyltransferase activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1987;2(8574):1486–1488. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92621-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rook GA, Steele J, Brealey R, Whyte A, Isenberg D, Sumar N, et al. Changes in IgG glycoform levels are associated with remission of arthritis during pregnancy. J Autoimmun. 1991;4(5):779–794. doi: 10.1016/0896-8411(91)90173-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van de Geijn FE, Wuhrer M, Selman MH, Willemsen SP, de Man YA, Deelder AM, et al. Immunoglobulin G galactosylation and sialylation are associated with pregnancy-induced improvement of rheumatoid arthritis and the postpartum flare: results from a large prospective cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(6):R193. doi: 10.1186/ar2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jefferis R, Lund J. Interaction sites on human IgG-Fc for FcgammaR: current models. Immunol Lett. 2002;82(1–2):57–65. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(02)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wormald MR, Rudd PM, Harvey DJ, Chang SC, Scragg IG, Dwek RA. Variations in oligosaccharide-protein interactions in immunoglobulin G determine the site-specific glycosylation profiles and modulate the dynamic motion of the Fc oligosaccharides. Biochemistry. 1997;36(6):1370–1380. doi: 10.1021/bi9621472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deisenhofer J. Crystallographic refinement and atomic models of a human Fc fragment and its complex with fragment B of protein A from Staphylococcus aureus at 2.9- and 2.8-A resolution. Biochemistry. 1981;20(9):2361–2370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sutton BJ, Phillips DC. The three-dimensional structure of the carbohydrate within the Fc fragment of immunoglobulin G. Biochem Soc Trans. 1983;11(Pt 2):130–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tao MH, Morrison SL. Studies of aglycosylated chimeric mouse-human IgG. Role of carbohydrate in the structure and effector functions mediated by the human IgG constant region. J Immunol. 1989;143(8):2595–2601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nose M, Wigzell H. Biological significance of carbohydrate chains on monoclonal antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80(21):6632–6636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.21.6632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leatherbarrow RJ, Rademacher TW, Dwek RA, Woof JM, Clark A, Burton DR, et al. Effector functions of a monoclonal aglycosylated mouse IgG2a: binding and activation of complement component C1 and interaction with human monocyte Fc receptor. Mol Immunol. 1985;22(4):407–415. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(85)90125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wright A, Morrison SL. Effect of altered CH2-associated carbohydrate structure on the functional properties and in vivo fate of chimeric mouse-human immunoglobulin G1. J Exp Med. 1994;180(3):1087–1096. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duncan AR, Winter G. The binding site for C1q on IgG. Nature. 1988;332(6166):738–740. doi: 10.1038/332738a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White KD, Cummings RD, Waxman FJ. Ig N-glycan orientation can influence interactions with the complement system. J Immunol. 1997;158(1):426–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soltys AJ, Hay FC, Bond A, Axford JS, Jones MG, Randen I, et al. The binding of synovial tissue-derived human monoclonal immunoglobulin M rheumatoid factor to immunoglobulin G preparations of differing galactose content. Scand J Immunol. 1994;40(2):135–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1994.tb03442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Malhotra R, Wormald MR, Rudd PM, Fischer PB, Dwek RA, Sim RB. Glycosylation changes of IgG associated with rheumatoid arthritis can activate complement via the mannose-binding protein. Nat Med. 1995;1(3):237–243. doi: 10.1038/nm0395-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Royle L, Campbell MP, Radcliffe CM, White DM, Harvey DJ, Abrahams JL, et al. HPLC-based analysis of serum N-glycans on a 96-well plate platform with dedicated database software. Anal Biochem. 2008;376(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shadick NA, Heller JE, Weinblatt ME, Maher NE, Cui J, Ginsburg G, et al. Opposing effects of the D70 mutation and the shared epitope in HLA-DR4 on disease activity and certain disease phenotypes in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(11):1497–1502. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.067603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Agarwal SK, Glass RJ, Shadick NA, Coblyn JS, Anderson RJ, Maher NE, et al. Predictors of discontinuation of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(9):1737–1744. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Majka DS, Deane KD, Parrish LA, Lazar AA, Baron AE, Walker CW, et al. Duration of preclinical rheumatoid arthritis-related autoantibody positivity increases in subjects with older age at time of disease diagnosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(6):801–807. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.076679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31(3):315–324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hill JA Al-Bishri J, Cairns E, Bell DA. Antibody reactivity to CCP, citrullinated fibrinogen, and a novel citrullinated peptide in patients with rheumatic disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(9 (Suppl)):S224. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hill JA, Al-Bishri J, Gladman DD, Cairns E, Bell DA. Serum autoantibodies that bind citrullinated fibrinogen are frequently found in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(11):2115–2119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hill JA, Cairns E, Bell DA. Peptides associated with HLA-DR MHC class II molecules involved in autoimmune diseases. WO 04/078098. Patent. 2004

- 52.Li M, Brintnell W, Bell DA, Cairns E. The arthritogenicity of human anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(9(Suppl)):S936. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parekh RB, Roitt IM, Isenberg DA, Dwek RA, Ansell BM, Rademacher TW. Galactosylation of IgG associated oligosaccharides: reduction in patients with adult and juvenile onset rheumatoid arthritis and relation to disease activity. Lancet. 1988;1(8592):966–969. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91781-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vander Cruyssen B, Van Looy S, Wyns B, Westhovens R, Durez P, Van den Bosch F, et al. DAS28 best reflects the physician’s clinical judgment of response to infliximab therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients: validation of the DAS28 score in patients under infliximab treatment. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7(5):R1063–R1071. doi: 10.1186/ar1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shikata K, Yasuda T, Takeuchi F, Konishi T, Nakata M, Mizuochi T. Structural changes in the oligosaccharide moiety of human IgG with aging. Glycoconj J. 1998;15(7):683–689. doi: 10.1023/a:1006936431276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamada E, Tsukamoto Y, Sasaki R, Yagyu K, Takahashi N. Structural changes of immunoglobulin G oligosaccharides with age in healthy human serum. Glycoconj J. 1997;14(3):401–405. doi: 10.1023/a:1018582930906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parekh R, Roitt I, Isenberg D, Dwek R, Rademacher T. Age-related galactosylation of the N-linked oligosaccharides of human serum IgG. J Exp Med. 1988;167(5):1731–1736. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.5.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Field MC, Amatayakul-Chantler S, Rademacher TW, Rudd PM, Dwek RA. Structural analysis of the N-glycans from human immunoglobulin A1: comparison of normal human serum immunoglobulin A1 with that isolated from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Biochem J. 1994;299(Pt 1):261–275. doi: 10.1042/bj2990261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bongi SM, Manetti R, Melchiorre D, Turchini S, Boccaccini P, Vanni L, et al. Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies are highly associated with severe bone lesions in rheumatoid arthritis anti-CCP and bone damage in RA. Autoimmunity. 2004;37(6–7):495–501. doi: 10.1080/08916930400011965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Greiner A, Plischke H, Kellner H, Gruber R. Association of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, anti-citrullin antibodies, and IgM and IgA rheumatoid factors with serological parameters of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1050:295–303. doi: 10.1196/annals.1313.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bang H, Egerer K, Gauliard A, Luthke K, Rudolph PE, Fredenhagen G, et al. Mutation and citrullination modifies vimentin to a novel autoantigen for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(8):2503–2511. doi: 10.1002/art.22817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mathsson L, Mullazehi M, Wick MC, Sjoberg O, van Vollenhoven R, Klareskog L, et al. Antibodies against citrullinated vimentin in rheumatoid arthritis: higher sensitivity and extended prognostic value concerning future radiographic progression as compared with antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptides. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):36–45. doi: 10.1002/art.23188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vis M, Bos WH, Wolbink G, Voskuyl AE, Twisk JW, Van de Stadt R, et al. IgM-rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide, and anti-citrullinated human fibrinogen antibodies decrease during treatment with the tumor necrosis factor blocker infliximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(3):425–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guler H, Turhanoglu AD, Ozer B, Ozer C, Balci A. The relationship between anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide and bone mineral density and radiographic damage in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2008;37(5):337–342. doi: 10.1080/03009740801998812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vanichapuntu M, Phuekfon P, Suwannalai P, Verasertniyom O, Nantiruj K, Janwityanujit S. Are anti-citrulline autoantibodies better serum markers for rheumatoid arthritis than rheumatoid factor in Thai population? Rheumatol Int. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00296-009-1058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van der Linden MP, van der Woude D, Ioan-Facsinay A, Levarht EW, Stoeken-Rijsbergen G, Huizinga TW, et al. Value of anti-modified citrullinated vimentin and third-generation anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide compared with second-generation anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide and rheumatoid factor in predicting disease outcome in undifferentiated arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(8):2232–2241. doi: 10.1002/art.24716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rademacher TW, Williams P, Dwek RA. Agalactosyl glycoforms of IgG autoantibodies are pathogenic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(13):6123–6127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.6123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.