Abstract

In this issue of Blood, Jitschin et al identify increased numbers of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) suppressing T cells and inducing regulatory T cells (Tregs), resulting in impaired immune responses.1

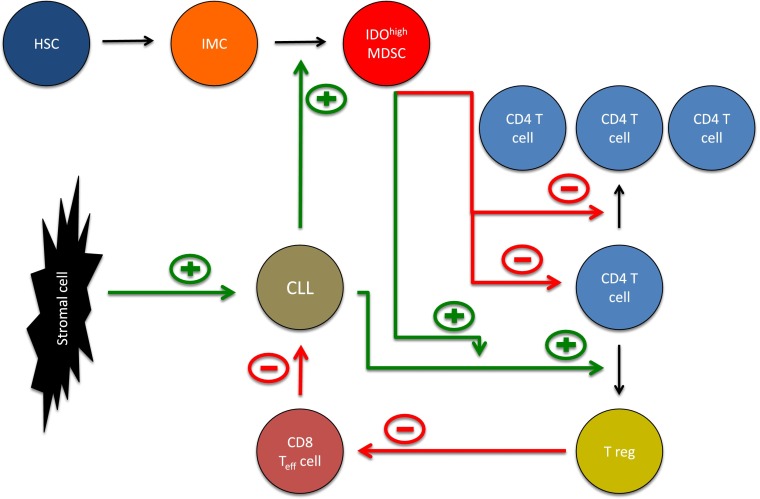

The role of IDOhigh MDSCs in the microenvironment of CLL. Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) give rise to immature myeloid cells (IMCs). The latter may differentiate into myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). CLL cells promote the generation of IDOhigh MDSCs suppressing T-cell activation and proliferation. In addition, IDOhigh MDSCs enhance the ability of CLL cells to promote conversion of naïve T cells into regulatory T cells (Tregs). Tregs in turn suppress the activity of cytotoxic CD8 T cells targeting CLL cells. Thus, MDSCs by multiple pathways promote CLL cell survival and suppression of the immune system. In addition, CLL cells are protected by direct interaction with stromal cells (eg, via CXCR4/CXCL12).

CLL is the most prominent B-cell malignancy among adults in the Western world, characterized by a clonal expansion of B cells. Early on, it coincides with a profound immunodeficiency, predisposing for infections and rendering the disease rather insensitive to conventional, and particularly immunotherapeutic strategies, leading to impaired antitumor immune responses. This resistance is largely mediated by the complex crosstalk between neoplastic B cells and the tissue microenvironment: Previous reports identified direct interaction of CLL cells with mesenchymal stromal cells and nurselike cells (eg, via the CXCR4-CXCL12 axis), promoting survival of CLL cells.2 Similarly, expansion of T cells considerably contributes to microenvironment-mediated CLL protection. Although in many cancers, T cells are involved in antitumor immunity, T cells in CLL fail to mount an effective T cell–mediated immune response against CLL cells.3 In particular, Tregs have been shown to increase in CLL, adding to the reduced immunosurveillance in CLL.4 Recently, a further major component of the microenvironment, the so-called “myeloid-derived suppressor cells” (MDSCs), has been identified in various malignancies including CLL and has been inversely linked with outcome.5 MDSCs represent a heterogeneous population of myeloid progenitors and precursors of granulocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. They can inhibit T-cell responses limiting immune therapeutic approaches and are induced by various factors expressed or secreted in states of cancer, inflammation, or trauma.6

In this issue of Blood, Jitschin et al characterize a subset of CD14+HLA-DRlo MDSCs expressing high amounts of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO).1 These MDSCs are increased in untreated CLL patients at a rather early stage and suppress both T-cell activation and proliferation. In a series of carefully designed experiments, the authors discover that CLL cells directly induce IDOhi MDSCs capable of inducing suppressive Tregs. At the same time, myeloid cells rendered CLL cells more likely to convert conventional T cells into Tregs (see figure). Interestingly, all effects depended on IDO expression because neutralizing antibodies against IDO abolished MDSC action. This meticulously performed study suggests that IDOhi MDSCs represent central regulators of immune function in CLL and may critically dampen antitumor immunity. These data imply that antagonizing suppressive functions of CLL MDSCs (eg, by pharmacologic inhibition of IDO) could provide an attractive approach for enhancing immune responses.

Various studies implicated IDO with progression of solid tumors such as non–small-cell lung carcinoma, colon carcinoma, cervical carcinoma, and breast cancer. IDO is an intracellular enzyme highly expressed in myeloid cells, with a catalytic function in the tryptophan pathway. Because tryptophan depletion results in the growth arrest of T cells, and degradation products of tryptophan may be toxic for CD8+ T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, IDO enfolds various immunosuppressive effects. In fact, genetic deletion of IDO was recently shown to directly limit tumorigenesis.7 On the basis of these findings, inhibitors of IDO are currently being challenged in several clinical trials as potential treatment or combination treatment of recurrent or refractory solid tumors. However, thus far only one trial has been launched in a hematologic malignancy, namely in myelodysplastic syndrome. This trial is still recruiting (registered at clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT01822691).

A very promising step in a similar direction is the recent finding that the programmed death-1 (PD1) receptor, a negative regulator of T-cell effector mechanisms limiting immune responses against cancer, is strongly upregulated in CLL cells.8 A phase 1 dose-escalation study of the anti-PD1 antibody CT-011 (pidilizumab) showed evidence of response in 6 of 18 patients with advanced hematologic malignancies; of the 3 CLL patients who were enrolled, two showed evidence of stable disease.9 Given the preclinical data highlighting the significance of the PD1:PDL1 axis in suppressing T-cell function in CLL, there is also a strong rationale that pharmacologic manipulation of the PD1:PDL1 axis may contribute to restoring T-cell functions in the CLL microenvironment. The therapeutic approach of blocking the PD1:PDL1 axis has also been pursued successfully in solid cancer: in patients with advanced melanoma, including those who had disease progression while they were receiving ipilimumab, treatment with the anti-PD1 antibody lambrolizumab (previously known as MK-3475) resulted in a high rate of sustained tumor regression.10

It will take time to validate the concept arising from the work of Jitschin et al in vivo. We will have to test whether antagonizing the suppressive function of MDSCs in CLL will ultimately limit this as yet incurable disease before this approach may be considered as a future therapeutic strategy for CLL and potentially incorporated into clinic rounds. In that context, the finding of the immunosuppressive network among CLL cells, MDSCs, and Tregs is highly intriguing and may be the final frontier of the microenvironment in CLL that we will have to overcome.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jitschin R, Braun M, Buttner M, et al. CLL-cells induce IDOhi CD14+HLA-DRlo myeloid-derived suppressor cells that inhibit T-cell responses and promote TRegs. Blood. 2014. 124(5):750–760. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Burger JA, Gribben JG. The microenvironment in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and other B cell malignancies: insight into disease biology and new targeted therapies. Semin Cancer Biol. 2014;24:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christopoulos P, Pfeifer D, Bartholomé K, et al. Definition and characterization of the systemic T-cell dysregulation in untreated indolent B-cell lymphoma and very early CLL. Blood. 2011;117(14):3836–3846. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-299321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Arena G, Laurenti L, Minervini MM, et al. Regulatory T-cell number is increased in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients and correlates with progressive disease. Leuk Res. 2011;35(3):363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gustafson MP, Abraham RS, Lin Y, et al. Association of an increased frequency of CD14+ HLA-DR lo/neg monocytes with decreased time to progression in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL). Br J Haematol. 2012;156(5):674–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08902.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindau D, Gielen P, Kroesen M, Wesseling P, Adema GJ. The immunosuppressive tumour network: myeloid-derived suppressor cells, regulatory T cells and natural killer T cells. Immunology. 2013;138(2):105–115. doi: 10.1111/imm.12036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith C, Chang MY, Parker KH, et al. IDO is a nodal pathogenic driver of lung cancer and metastasis development. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(8):722–735. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0014. 10.1158/2159-8290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grzywnowicz M, Zaleska J, Mertens D, et al. Programmed death-1 and its ligand are novel immunotolerant molecules expressed on leukemic B cells in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4):e35178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berger R, Rotem-Yehudar R, Slama G, et al. Phase I safety and pharmacokinetic study of CT-011, a humanized antibody interacting with PD-1, in patients with advanced hematologic malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(10):3044–3051. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, et al. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(2):134–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]