Abstract

We report a case of symptomatic hypomagnesaemia in medical intensive care unit that is strongly related to proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and provide literature review. A 65-year-old male with severe gastroesophageal reflux on omeprazole 20 mg orally twice a day, who presented to the hospital with abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea, and new onset seizures. On admission, his serum magnesium level was undetectable. Electrocardiogram showed a new right bundle branch block with a prolonged QT interval. The hypomagnesemia was corrected with aggressive magnesium supplementation and hypomagnesemia resolved only after the PPI was stopped. Neurologic and cardiac abnormalities were corrected. This is a life-threatening case of an undetectable magnesium level strongly associated with PPI use. In critically, ill patients with refractory hypomagnesemia, we advocate considering changing gastrointestinal prophylaxis from a PPI to a histamine-receptor blocker.

Keywords: Gastroesophageal reflux, hypomagnesemia, proton pump inhibitors, seizures

Introduction

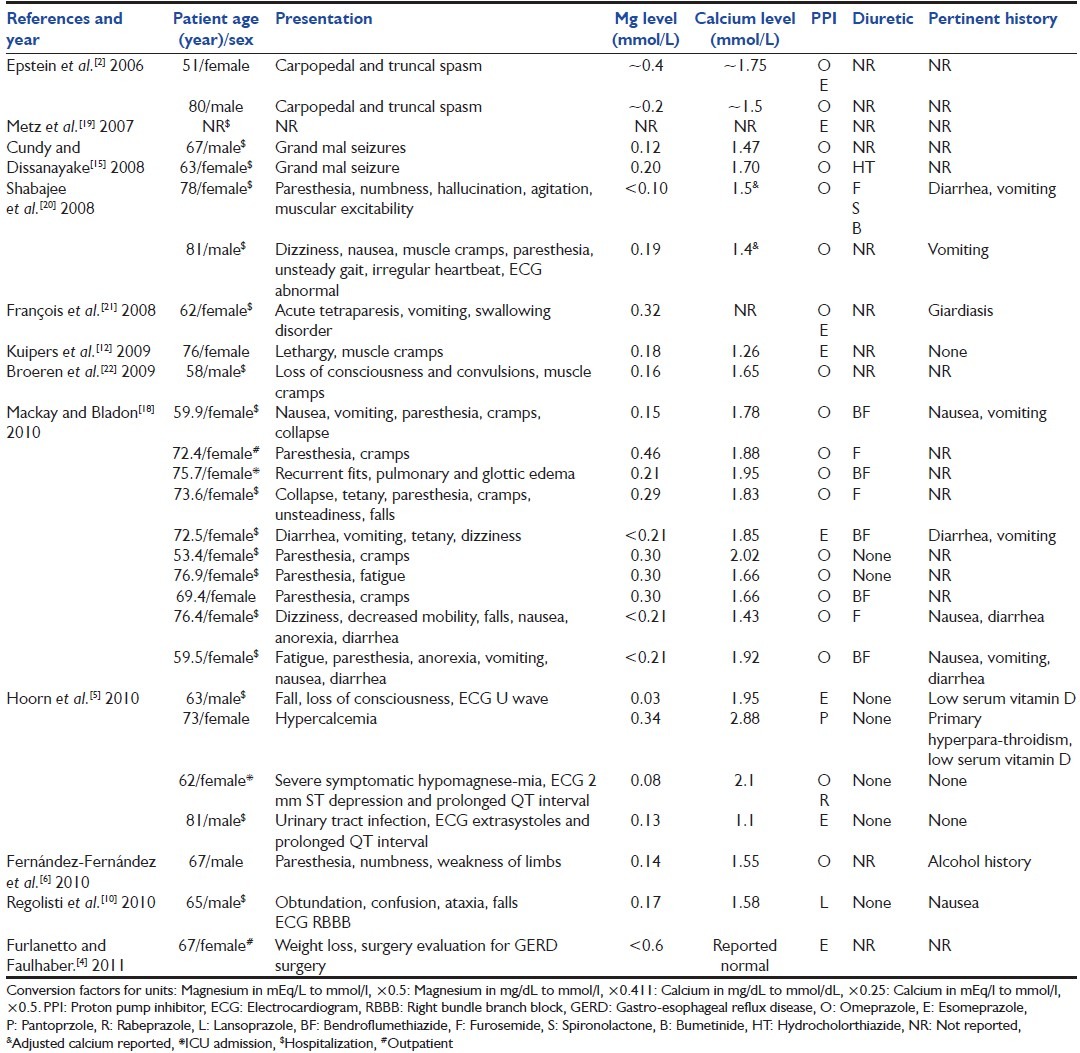

In March 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration notified the public that taking proton pump inhibitor (PPI) drugs for prolonged periods of time may be associated with low serum magnesium (SMg) levels.[1] Since this finding was first noted in 2006 by Epstein et al.,[2] approximately 27 cases of PPI-induced hypomagnesaemia have been reported in the literature. Only two cases have reported admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) with contributory factors to the hypomagnesaemia. We report a rare case of life-threatening PPI-related hypomagnesaemia, to the best of our knowledge it is a first case of undetectable SMg (0.0 mg/dL or mmol/l).

Case Report

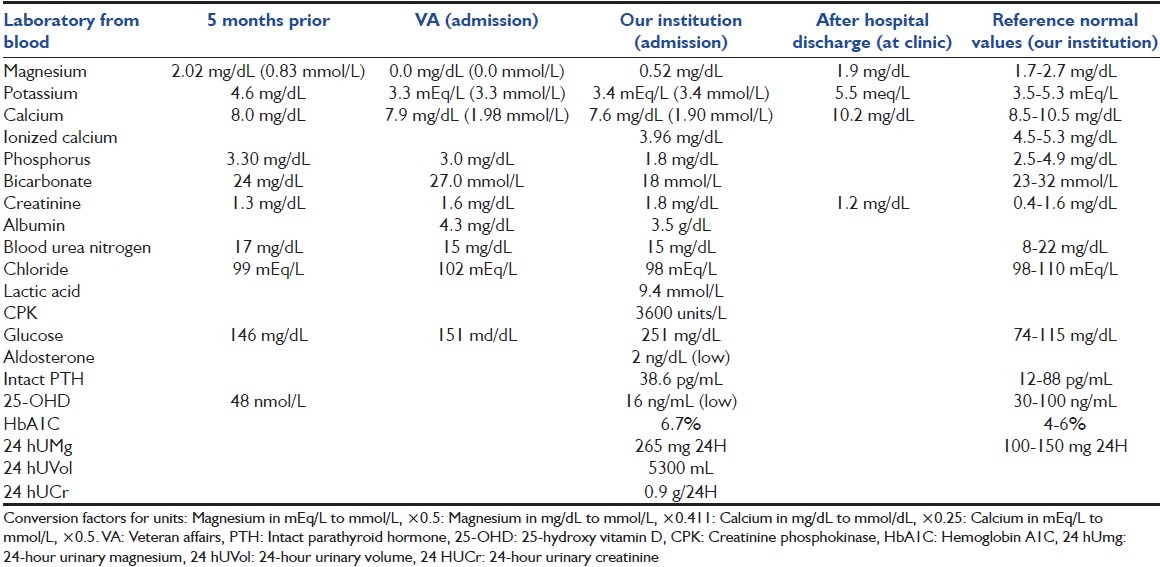

A 65-year-old male with medical history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, remote stroke, and severe gastroesophageal reflux presented to his Veteran Affairs (VA) clinic with 2 days of generalized abdominal pain, nausea, and watery diarrhea (6-8 episodes over 24-h). His medications included amlodipine, aspirin, vitamin D, lisinopril, metformin, pravastatin, and omeprazole (20 mg daily for 1.5 years). He had no history of neck surgery, remote or recent alcoholism, starvation, diuretic use, thyroid disease, chronic diarrhea, steatorrhea, or malabsorption. To he was sent VA emergency department (ED) and laboratory [Table 1][3] showed hypomagnesemia at 0.0 mg/dL, hypocalcaemia at 7.9 mg/dL (1.98 mmol/l), and sinus tachycardia (120 beats/min) and right bundle branch block (RBBB) with prolonged QT on electrocardiogram (ECG). He left the ED against medical advice due to agitation. He had normal SMg 5 months earlier [Table 1].

Table 1.

Laboratory values at VA and our institution on admission and 5 months prior

He was brought to our ED after a seizure episode a few hours later at home. On arrival, he had tachycardia, rapid and shallow breathing, and was combative and disoriented. He was intubated for airway protection and admitted to ICU for seizure and aspiration pneumonia (left lower lobe infiltrate). His physical exam was significant for hyperreflexia and thick yellow secretions. Laboratory studies at our institution revealed severe hypomagnesaemia at 0.52 mg/dL (normal 1.7-2.7 mg/dL), hypocalcaemia at 7.6 mg/dL and hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia, elevated serum creatinine (SCr) and creatinine phosphokinase (CPK level), and anion gap metabolic acidosis with lactic acidosis [Table 1]. Urinalysis revealed mild hyaline cast without ketones. Fractional sodium excretion was 0.39% and urine to plasma creatinine ratio was 167 suggesting prerenal azotemia. 24-h urinary magnesium (24 hUMg) was 265 mg (with urinary volume was 5300 mL) and SMg level normalized to 2.17 mg/dL (0.89 mmol/l) on day 3 (after receiving 8 g of intravenous [IV] magnesium sulfate). After aggressive hydration, electrolyte repletion and sedation, the acidosis, CPK levels, and SCr normalized. His diarrhea resolved on the 2nd day. Electroencephalogram and magnetic radiographic imaging of the brain were unremarkable.

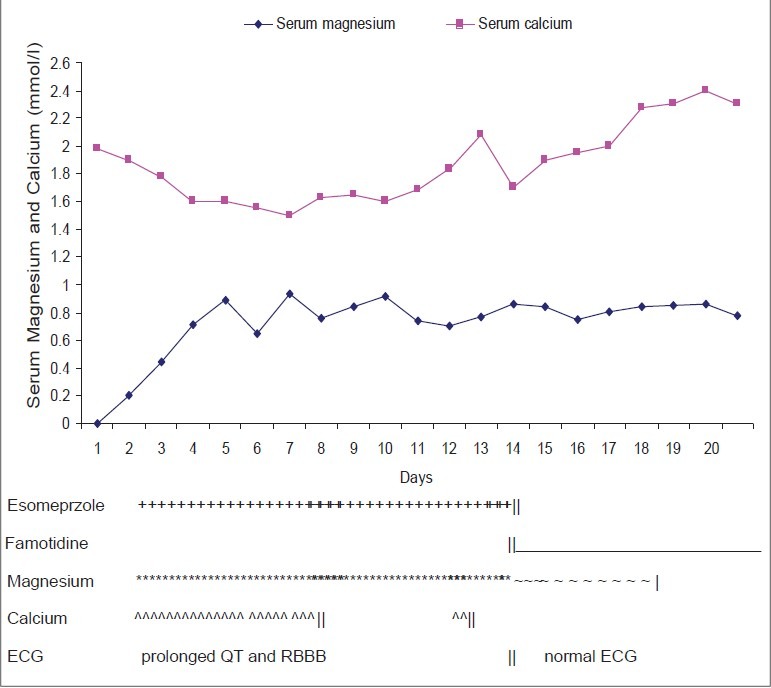

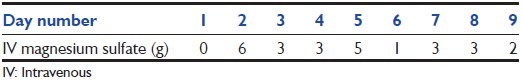

In the ICU, he received esomeprazole for gastrointestinal (GI) prophylaxis. After 8 days of unsuccessful supplementation with IV magnesium sulfate (total of 23 g), esomeprazole was changed to famotidine 20 mg IV twice daily [Figure 1[3] and Table 2]. He was continued on oral magnesium oxide 400 mg 3 times daily for 5 days. He received furosemide on day 5-7. SMg and calcium levels remained normalized after oral magnesium was discontinued. Repeated ECG converted to sinus rhythm. Subsequently, patient was discharged home and seen at clinic without any significant neurologic deficits and with normal laboratory [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Serum magnesium and calcium level changes

Table 2.

Grams of IV magnesium supplementation given during hospitalization

Discussion

Presentations of hypomagnesemia range from asymptomatic in mild deficiency, to nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, muscle weakness and spasms, tetany, paresthesia, ataxia, irritability, seizures and life-threatening arrhythmias (sinus tachycardia, supraventricular or ventricular arrhythmia).[4,5,6,7] Magnesium deficiency has been observed with GI or renal losses, and changes in extracellular fluid. Impaired GI causes include malabsorption, vitamin D deficiency, severe vomiting, or diarrhea.[7] Impaired renal tubular reabsorption includes increased flow, decreased tubular reabsorption, genetic disorders (Gitelman and Bartter syndrome) and acquired acute tubular necrosis, drugs, or toxins (diuretics or alcohol).[7] Secondary causes include shifts in extracelluar fluid volume (in metabolic acidosis) and recovery from metabolic acidosis (which causes intracellular losses), extensive burns, and postparathyroidectomy.[6,7] Common causes of hypomagnesaemia in the ICU include medications, parental nutrition, acute pancreatitis, refeeding syndrome, and hypoalbuminemia.[7,8] PPI-related hypomagnesaemia has been reported, especially with the long term use of omeprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole.[1,5]

Magnesium is absorbed in both intestine and kidneys and is excreted in the kidney. Intestinal absorption occurs by either paracelluar simple diffusion (at high concentration) and transcelluar active transport (at low magnesium concentration),[9,10] and is dependent on epithelial electrical voltage.[11] Kidneys reabsorb most of the filtered magnesium by passive diffusion (10-5% in proximal tubule and 65-75% in thick ascending limp of loop of henle) and about 10% by active transport in distal convoluted tubule through transient receptor potential melastin (TRPM) 6 and 7[9,10,11] TRPM 6 (expressed in both intestines and kidneys) and 7 (omnipresent) are proteins that functions as cation channels or protein kinases and as magnesium sensor or transporter.[12,13,14]

The precise mechanism of PPI induced hypomagnesemia has not been fully understood; however, the postulated mechanisms to date synthesize that PPI could promote magnesium loss in intestine and kidneys through active and passive transport pathway.[10] Several reports have implicated intestinal pH changed, and charged form of magnesium related to PPI use may have reduced the absorption of magnesium and affected TRPM 6 (heterozygous mutation) or 7 function.[6,9,10,11,12,15] Fernαndez-Fernαndez et al. noted polymorphism of TRPM6 gene in hypomagnesaemic patient on PPI, with unclear effect on renal and intestinal magnesium handling and hypomagnesemia also occurred in without TRMP6 gene mutation.[6] Glutamates in the pore region of TRPM6/7 may have a role in pH sensitivity.[16] Omeprazole decreased paracellular magnesium passage.[17]

Our case is unique for several reasons. To the best of our knowledge, it is first case report of SMg level of 0.0 g/dL secondary to PPI-related hypomagnesaemia with reversible life-threatening manifestations of severe agitation, new onset seizures, rhabdomyolysis, renal insufficiency, and QT prolongation with a new RBBB on ECG, which resolved after correction of hypomagnesemia. Our patient had multiple factors contributing to rhabdomyolysis, which may have developed after severe hypomagnesemia, acute hypophosphatemia, and a seizure episode.[7] Furthermore, since hypomagnesaemia may be present in up to 50% of critically ill patients,[8] and most of these patients will require GI prophylaxis.

Urinary magnesium excretion approximates SMg level and usually matches net intestinal absorption. Due to critical presentation of our patient, we did not have 24 hUMg prior to initiation of magnesium replacement. Although, our patient did not have apparent renal disorder, his increased 24 hUMg excretions was likely due to aggressive magnesium supplementation and hydration with impaired renal conservation above physiologic absorptive capacity (50-70% of daily magnesium dose is retained during initial replacement).[7] Cundy and Dissanayake implied in their magnesium infusion test that prolonged use of PPI may have impaired active transport absorption of magnesium and that abrupt increase in UMg excretion when ultrafiltrable SMg >1 mEq/L suggesting defective tubular reabsorption of magnesium.[15] Regolisti et al. observed subtle defect in renal conservation of magnesium and speculated that long term PPI user with heterozygous gene mutation may have diminished function of genes (TMPR6, FXYD2, KCNJ10, or KCNA1) that are involved in magnesium reabsorption in the distal nephron and possibly in the intestine.[10]

This case also illustrates that in certain patients the choice of a PPI may actually slow the correction of hypomagnesaemia. Our patient's diarrhea is unlikely to explain the severely low magnesium level, and his calcium and potassium level were not as severely low as other reported cases [Table 3].[3] The lactic acidosis (probably due to seizures, rhabdomyolysis and metformin use) may have caused the discrepancy in magnesium levels (0.00 mg/dL and 0.52 mg/dL) between the two institutions. Acidosis is known to falsely elevate plasma magnesium levels.[9]

Table 3.

Published cases of PPI-induced hypomagnesemia

Our patient's transient hypocalcaemia is associated with secondary hypoparathyroidism related to profound hypomanesaemia, which causes both peripheral resistance and suppression of PTH synthesis. Epstein et al. have reported two patients who had hypomagnesemic hypoparathyrodism and electrolyte abnormalities resolved after PPI was discontinued.[2] Coexistence of vitamin D deficiency may require supplementation with vitamin D[7] like in our patient.

In case of severe hypomagnesemia suspected from PPI use, physician can switch to histamine-2-receptor (H2R) antagonist, another PPI or perform a withdrawal test while monitoring magnesium level. In Mackay and Bladon hypomagnesemia recurred when PPI were re-challenged for dyspepsia; however, it did not redevelop with pantoprazole (least potent PPI), when combined with oral magnesium supplements.[18] Combination of pantoprozole alternating with famotidine while on oral magnesium supplement may work as well.[6] It takes many years to develop PPI induced hypomagnesemia and concurrent use of diuretics may facilitate development of hypomagnesemia by favoring magnesium loss through kidney, but not impairing intestinal absorption of magnesium.[18] SMg needs to be monitored while on long term PPI therapy correlated with clinical symptoms as described above.22

Conclusion

In ICU patients with diabetes, cardiac or neurologic disorders, we recommend routine monitoring of electrolytes and magnesium levels during PPI use. In critically, ill patients on PPIs used for prevention of and treatment of stress-induced upper GI bleeding, we recommend considering changing to an H2R antagonist when SMg levels fail to respond to aggressive supplementation and ruling out other causes of reversible hypomagnesaemia.

Acknowledgments

Sabrina Felson, MD, VA NY Harbor Healthcare for her contribution to this case Pius O. Ochieng, MD, and Isaac Sachmechi, MD, Queens Hospital Center of Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Fda.gov. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Low magnesium levels can be associated with long-term use of proton-pump inhibitor drugs (PPIs) Drug Safety Communication. [2011 Mar 02]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm245011.htm .

- 2.Epstein M, McGrath S, Law F. Proton-pump inhibitors and hypomagnesemic hypoparathyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1834–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc066308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Globalrph.com. Globalrph: The clinician ultimate reference. [Last accessed 2011 Oct 14]. Available from: http://www.globlarph.com/conversional_si.htm .

- 4.Furlanetto TW, Faulhaber GA. Hypomagnesemia and proton pump inhibitors: Below the tip of the iceberg. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1391–2. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoorn EJ, van der Hoek J, de Man RA, Kuipers EJ, Bolwerk C, Zietse R. A case series of proton pump inhibitor-induced hypomagnesemia. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:112–6. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernández-Fernández FJ, Sesma P, Caínzos-Romero T, Ferreira-González L. Intermittent use of pantoprazole and famotidine in severe hypomagnesaemia due to omeprazole. Neth J Med. 2010;68:329–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bringhurst FR, Demay MB, Krane SM, Kronenberg HM. Bone and mineral metabolism in health and disease. In: Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Faui AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, editors. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 16th ed. United States of America: McGraw-Hill Publishers; 2005. pp. 2238–49. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buckley MS, Leblanc JM, Cawley MJ. Electrolyte disturbances associated with commonly prescribed medications in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(6 Suppl):S253–64. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181dda0be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pham PC, Pham PM, Pham SV, Miller JM, Pham PT. Hypomagnesemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:366–73. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02960906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Regolisti G, Cabassi A, Parenti E, Maggiore U, Fiaccadori E. Severe hypomagnesemia during long-term treatment with a proton pump inhibitor. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:168–74. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cundy T, Mackay J. Proton pump inhibitors and severe hypomagnesaemia. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2011;27:180–5. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32833ff5d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuipers MT, Thang HD, Arntzenius AB. Hypomagnesaemia due to use of proton pump inhibitors: A review. Neth J Med. 2009;67:169–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmitz C, Perraud AL, Fleig A, Scharenberg AM. Dual-function ion channel/protein kinases: Novel components of vertebrate magnesium regulatory mechanisms. Pediatr Res. 2004;55:734–7. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000117848.37520.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chubanov V, Schlingmann KP, Wäring J, Heinzinger J, Kaske S, Waldegger S, et al. Hypomagnesemia with secondary hypocalcemia due to a missense mutation in the putative pore-forming region of TRPM6. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7656–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611117200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cundy T, Dissanayake A. Severe hypomagnesaemia in long-term users of proton-pump inhibitors. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;69:338–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li M, Du J, Jiang J, Ratzan W, Su LT, Runnels LW, et al. Molecular determinants of Mg2+ and Ca2+ permeability and pH sensitivity in TRPM6 and TRPM7. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25817–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608972200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thongon N, Krishnamra N. Omeprazole decreases magnesium transport across Caco-2 monolayers. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1574–83. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i12.1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mackay JD, Bladon PT. Hypomagnesaemia due to proton-pump inhibitor therapy: A clinical case series. QJM. 2010;103:387–95. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcq021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Metz DC, Sostek MB, Ruszniewski P, Forsmark CE, Monyak J, Pisegna JR. Effects of esomeprazole on acid output in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome or idiopathic gastric acid hypersecretion. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2648–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shabajee N, Lamb EJ, Sturgess I, Sumathipala RW. Omeprazole and refractory hypomagnesaemia. BMJ. 2008;337:a425. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39505.738981.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.François M, Lévy-Bohbot N, Caron J, Durlach V. Chronic use of proton-pump inhibitors associated with giardiasis: A rare cause of hypomagnesemic hypoparathyroidism? Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2008;69:446–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ando.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Broeren MA, Geerdink EA, Vader HL, van den Wall Bake AW. Hypomagnesemia induced by several proton-pump inhibitors. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:755–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]