Abstract

Aim:

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) are effective in treating anxiety disorders associated with major depressive disorder (MDD). This randomized, controlled, parallel-group, open-label, phase 4 trial (CTRI/2012/08/002895) was undertaken to compare the effectiveness and safety of desvenlafaxine versus escitalopram, a standard antidepressant.

Materials and Methods:

Effectiveness was assessed using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D17) and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A). Response to treatment was assessed by ≥50% decrease of baseline scores (responder rate). Safety and tolerability was evaluated by changes in routine laboratory parameters, vital signs, and adverse events reported by the subject and/or observed by the clinician.

Results:

Responder rates for both HAM-A and HAM-D scores at 8 weeks were better in the escitalopram group compared to the desvenlafaxine group (HAM-A 76.92% vs. 71.05%; HAM-D 79.48% vs 73.68%) but the differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.59 and P = 0.61). Within group changes of both scores, from baseline to subsequent visits in both treatment arms were statistically significant (P < 0.01).

Conclusion:

The effectiveness of desvenlafaxine was comparable to escitalopram, but escitalopram was better tolerated.

KEY WORDS: Anxiety, clinical trial, desvenlafaxine, escitalopram, major depressive disorder

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a mental disorder characterized by low mood, low self-esteem, and loss of interest in normally enjoyable activities, the changes lasting for a minimum period of two weeks and causing impairment in social, occupational, sleeping and eating habits, general health, or other important areas of functioning. The prevalence of MDD in India ranges from 1.7 to 74 per thousand population.[1,2] Depression is characterized by a typically chronic course with associated anxiety symptoms as co-morbidity.[3,4] Associated anxiety symptoms may result in greater symptom severity, higher suicidal risk, and poor treatment response than either depression or anxiety alone.[5] A significant overlap exists in the pathophysiologic components of depression and anxiety involving serotonergic, noradrenergic, and GABAergic systems in brain and their treatment.[6] The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) are reported to be effective in treating anxiety disorders associated with MDD.[6,7,8]

Desvenlafaxine is a SNRI that received United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) approval in February 2008 for the treatment of MDD, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, and social anxiety disorders; in India, Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO) approved desvenlafaxine on July 2009 for MDD.[9] Desvenlafaxine's novelty lies in the fact that it inhibits both norepinephrine and serotonin uptake. Escitalopram, a SSRI is approved for MDD and GAD in adults and children over 12 years of age. Head-to-head comparison of the two drugs in general population is lacking except one such trial conducted on post-menopausal patients. Reviews and systemic analysis on SSRIs and SNRIs have conflicting results. Therefore, this study was undertaken to compare the clinical effectiveness and safety of desvenlafaxine versus the standard antidepressant, escitalopram in patients with MDD associated with symptoms of anxiety.

Materials and Methods

The study was a randomized, controlled, parallel group, open label, phase 4 trial. Eligible subjects were adults ≥18 years and ≤60 years and of either sex who attended the Psychiatry outdoor clinic of a teaching hospital in eastern India with a clinical diagnosis of MDD as per Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TSR).[10] Subjects with a baseline Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) score[11] of 7-18 (mild and moderate depression cases) and a baseline Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A)[12] score ≥12 (vide infra) were included. Exclusion criteria included pregnant, lactating women, suicidal tendencies, catatonic features, patients on antidepressants for last one month, concurrent medical illnesses (hypertension, uncontrolled diabetes, ischemic heart disease, chronic renal failure, cirrhosis, malignancy), subjects with other coexistent psychiatric disorders (e.g. associated psychotic and maniac features, dementia, low I.Q, obsessive compulsive disorders) or subjects on drugs (quetiapine, duloxetine, buproprion, cough preparations, aspirin, fluoxetine, sertraline, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants), which are known to interact with the study medications.[13] The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (approval ref. number IEC/1055) and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects or their legally acceptable relative (LAR) as applicable. The trial was registered with Clinical Trial Registry India (CTRI/2012/08/002895).

Successive eligible patients were randomized (unstratified) using a computer generated random number table with 1:1 allocation ratio to receive either desvenlafaxine (50 mg) or escitalopram (10 mg) once daily for a period of 8 weeks. Responder rate was defined as ≥50% of baseline HAM-D score improvement at the 4th and 8th week visit. Allocation concealment was done by sequentially numbered sealed opaque envelopes. The study medications were purchased by the department for trial purpose and the entire consignment (both study drug and comparator) were of the same manufacturer. The manufacturing company had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The effectiveness outcome measures were changes from baseline to study end of HAM-D17 and HAM-A. The HAM-D scale is a 17-21 items observer scale to assess the presence and severity of depressive state in patients, amongst the first 17 items, 9 items are scored 0-4 (0 = absent, 1 = doubtful or slight, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = severe) whereas the next 8 items are scored 0-2 (0 = absent, 1 = doubtful or slight, 2 = clearly present). The HAM-A scale consists of 14 items, each defined by a series of symptoms, and measures both psychic anxiety (mental agitation and psychological distress) and somatic anxiety (physical complaints related to anxiety). Response to treatment was assessed by ≥50% decrease in HAM-D and HAM-A score. Safety assessment included changes in vital signs and treatment emergent adverse effects-those reported by the subjects and those elicited by the clinician at every visit. Laboratory investigations viz., hematogram (hemoglobin, total leucocyte count, differential leucocyte count, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate), liver function test, and serum urea and creatinine were done at baseline and at study end visit as a part of safety check.

Study Visits

Detailed clinical history, drug history, and baseline HAM-D and HAM-A scores were recorded in a pre-designed case report form. Three post-baseline visits were scheduled at 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks after randomization. At each follow-up visit, they were evaluated clinically using HAM-D and HAM-A rating scores. Drug dispensing was done at baseline and at week 4. History about the occurrence of any adverse event was also taken. Compliance check was also done using the pill counting method. Evaluation of the effectiveness and safety parameters were done in all subsequent follow-up visits as described above.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size calculation was based on changes in the primary outcome variable (HAM-D score). With a 80% power, α = 0.05, standard deviation of HAM-D score of 3, effect size of 2 with equal allocation ratio, the number of evaluable subjects required per group was 36. However, assuming a 20% dropout rate, we recruited 43 subjects per group in the study. The sample size was calculated using Statistica statistical software.

Effectiveness analysis was done by modified intention- to-treat basis whereby subjects who had baseline and at least one post-baseline data of HAM-D and HAM-A were evaluable. Missing visit data were substituted by the last observation carried forward strategy. For safety analysis, all randomized subjects who had received at least one dose of the trial medication were considered evaluable. Continuous variables (normal distribution) were compared between groups by independent sample t-test and within group by paired t-test. For between group comparisons of non-parametric variables, Mann–Whitney U test and for within group comparison Friedman's ANOVA followed by post-hoc Dunn test were used. Categorical data were compared using Chi-square or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Value of P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS version 17 statistical software was used for analysis.

Results

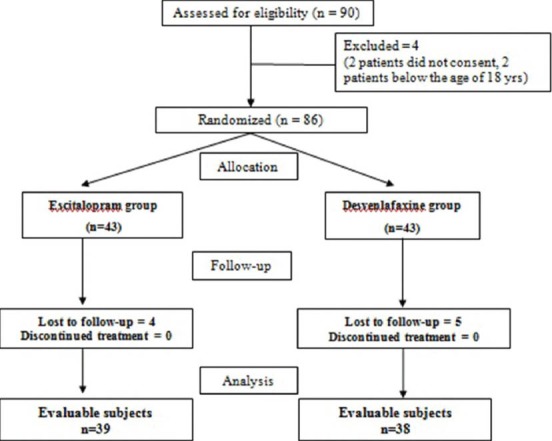

The flowchart of study participants is depicted in Figure 1. Of the 86 randomized subjects, 77 (escitalopram group = 39, desvenlafaxine group = 38) were evaluable as per the modified intention-to-treat analysis, since 9 subjects were lost to follow up. The mean age in the escitalopram group was 40 ± 10.6 years and in the desvenlafaxine group was 41.9 ± 8.5 years; the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.27). A total 64.1% were males in the escitalopram group and 60.5% in the desvenlafaxine group. The disease duration at screening were also comparable (P = 0.19) between groups. No concomitant psychiatric medications were used, as elicited during drug history; however, 5 subjects (3 in test and 2 in control) were on anti-hypertensives and were well-controlled throughout their study period.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flowchart of study participants

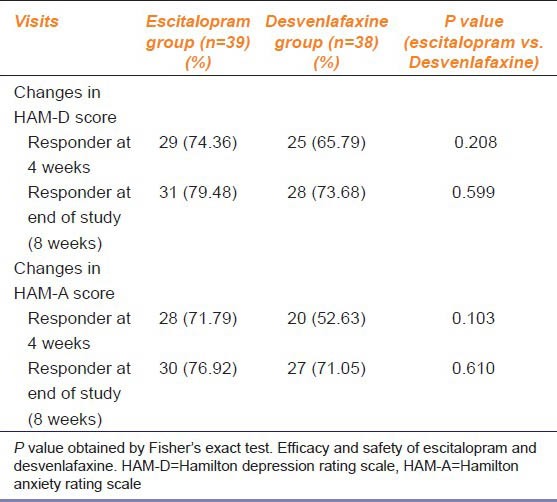

Baseline HAM-D (P = 0.63) were comparable in the two treatment arms. The responder rates defined as ≥50% improvement in HAM-D score from baseline at 8 weeks were 79.48% in the escitalopram group versus 73.68% in the desvenlafaxine group; the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.59). Responder rates for HAM-A score at 8 weeks were 76.92% and 71.05% in the escitalopram and desvenlafaxine groups, respectively. The difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.61) [Table 1]. The responder rates assessed at 8 weeks visit for both HAM D and HAM A were higher in the escitalopram group compared to the desvenlafaxine group, though the difference was not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Number of patients responding to ≥50% decrease in HAM-D and HAM-A scores

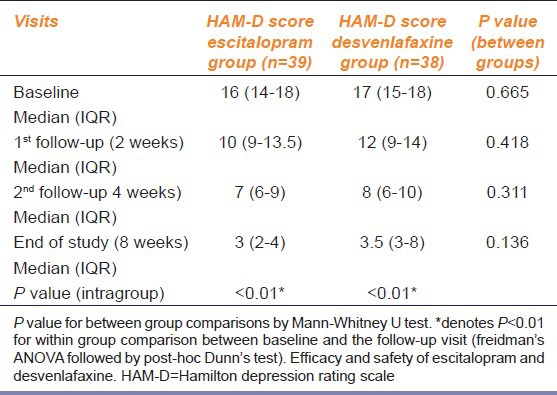

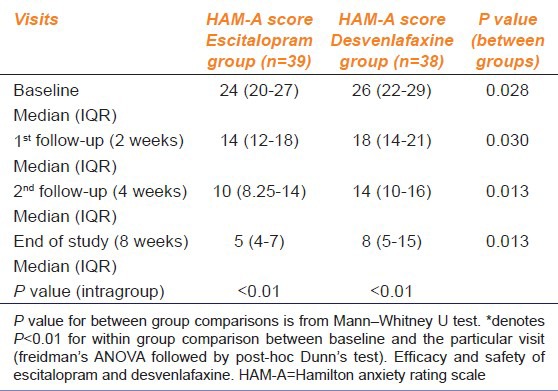

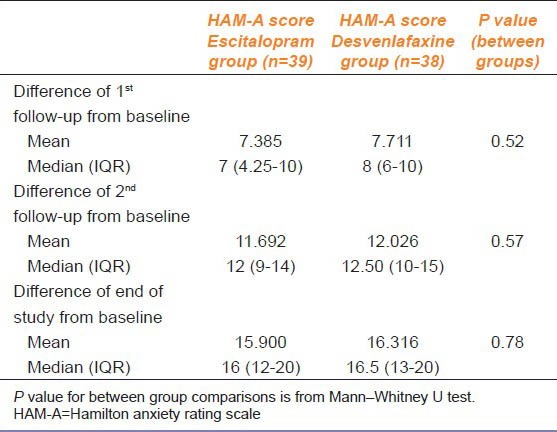

HAM-D scores showed comparable results at all visits. However, escitalopram faired significantly better in HAM-A scores than desvenlafaxine at all visits. Comparison of HAM-D and HAM-A scores are listed in Table 2, 3, and 4.

Table 2.

Between group comparison of HAM-D scores

Table 3.

Between group comparison HAM-A scores

Table 4.

Between group comparison of changes in HAM-A score from baseline

Within group changes of both scores, from baseline to subsequent visits in both treatment arms, were statistically significant (P < 0.01). Between groups comparison of the median HAM-D scores showed no significant changes, but there was a statistically significant difference in HAM-A scores between the treatment arms both at baseline, subsequent follow-up visits, and at the end of the study.

Safety data analysis revealed that 10 out of 39 subjects (25.64%) in the escitalopram group and 14 out of 38 (36.84%) in the desvenlafaxine group reported at least one adverse event. However, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.33). The common adverse events were nausea, vomiting, discomfort, insomnia, somnolence, and fatigue. Nausea occurred more frequently in the desvenlafaxine group than in the escitalopram group. All adverse events were non-serious and mild in severity and did not require treatment interruption or study drug withdrawal. Laboratory parameters were comparable at baseline and at the end of study.

Discussion

The study results indicate that both escitalopram and desvenlafaxine, which are widely used antidepressants, were also beneficial in reducing anxiety symptoms. The effectiveness of both drugs in controlling anxiety symptoms in MDD subjects appear to be comparable as there was no statistically significant difference in the responder rates. However, comparison of absolute anxiety scores showed a statistically significant difference between groups. This difference was, however, present since baseline; therefore, this baseline difference could attribute to the differences in subsequent visits. Reduction of median HAM-A score was more in the escitalopram group (baseline 24-5 at the end of study) compared to the desvenlafaxine group (baseline 26-14 at the end of study). In clinical practice, a ≥50% decrease in the scores holds greater relevance than an absolute score decrease. Since the 50% responder rate were similar in both the groups in the follow-up visits, escitalopram and desvenlafaxine have comparable effectiveness in controlling symptoms of anxiety with depression. Our result findings were in concurrence with a randomized, double blind placebo-controlled, multicenteric, flexible dose trial in adult subjects of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) by Bose A et al., where escitalopram was compared with venlafaxine extended release; the overall efficacy analysis suggested that escitalopram and venlafaxine are both effective treatments for GAD, but escitalopram was better tolerated.[14] Also, Soares et al. compared the efficacy and safety of desvenlafaxine and escitalopram in MDD with symptoms of anxiety in postmenopausal women, and the study demonstrated that there was no significant difference in their efficacy as evaluated on HAM-D17 scores.[15] Desvenlafaxine treatment achieved ≥50% response in 56-58% (HAM-D Score) and 41-48% (HAM-A Score) of patients. Our study achieved a higher response rate, 73.68% in HAM-D score and 73.7% in HAM-A score. Also, a review conducted by Ali and Lam showed that escitalopram demonstrates better efficacy than other SSRIs and similar efficacy to SNRIs which is consistent with the results of our study.[16] However, a systematic review on the comparative effectiveness of various SSRIs and SNRIs on MDD accompanied by anxiety or insomnia or pain in 19 head-to-head trials suggested that SSRIs do not differ in effectiveness, though the evidence was moderate in nature.[17] The current study is consistent with previously reported individual results and adverse events for the study medications.[18,19,20,21,22] In terms of tolerability, escitalopram was better tolerated than desvenlafaxine, as escitalopram indicated lesser incidence of adverse effects.

The study limitations were that we could not undertake a double blind study due to logistic reasons and a longer active duration of treatment would be more informative.

Conclusion

Over the last two decades, there has been much progress in our understanding of epidemiology, neurology, and treatment of depression and anxiety disorders. Whilst SSRIs are regarded as first-line treatment in most depression and anxiety disorders, SNRIs are receiving increasing considerations and desvenlafaxine received regulatory approval. In conclusion, this study indicates that desvenlafaxine is comparable to escitalopram in patients of depression with symptoms of anxiety, and escitalopram is better tolerated. Nevertheless, differences in tolerability and cost also must be considered when choosing therapies.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nill

Conflict of Interest: No

References

- 1.Reddy MS. Depression: The disorder and the burden. Indian J Psychol Med. 2010;32:1–2. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.70510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of twelve-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belzer K, Schneier FR. Comorbidity of anxiety and depressive disorders: Issues in conceptualization, assessment, and treatment. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10:296–306. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200409000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Liu J, Swartz M, Blazer DG. Comorbidity of DSM-III-R major depressive disorder in the general population: Results from the US National comorbidity survey. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1996:17–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldwin DS, Lopes AT. The influence of comorbid anxiety disorders on outcome in major depressive disorder. Medicographia. 2009;31:126–31. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keller MB, Krystal JH, Hen R, Neumeister A, Simon NM. Untangling depression and anxiety: Clinical challenges. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1477–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ballenger JC. Overview of different pharmacotherapies for attaining remission in generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 19):11–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papakostas GI, Trivedi MH, Alpert JE. Efficacy of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of anxiety symptoms in major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis of individual patient data from 10 double-blind randomized clinical trials. J Psychiatry Res. 2008;42:134–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.List of Approved Drug for Marketing in India (from 01.01.2009 to 30.12.2009) [Last accessed on 2014 May 01]. Available from: http://www.medlineindia.com/list%20of%20approved%20drugs.html .

- 10.Rush JA, Kellar MB, Bauer MS. American Psychiatric Association(APA) 4th ed. Washigton DC: APA; 2000. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders; pp. 356–61. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamilton MA. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neursurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32:50–5. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spina E, Trifiro G, Caraci F. Clinically significant drug interactions with newer antidepressants. CNS Drugs. 2012;26:39–67. doi: 10.2165/11594710-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bose A, Korotzer A, Gommoll C, Li D. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of escitalopram and venlafaxine XR in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:854–61. doi: 10.1002/da.20355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soares CN, Thase ME, Clayton A, Guico-Pabia CJ, Focht K, Jiang Q, et al. Desvenlafaxine and escitalopram for the treatment of postmenopausal women with major depressive disorder. Menopause. 2010;17:700–11. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181d88962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ali MK, Lam RW. Comparative efficacy of escitalopram in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:39–49. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S12531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thaler KJ, Morgan LC, Van Noord M, Gaynes BN, Hansen RA, Lux LJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of second-generation antidepressants for accompanying anxiety, insomnia, and pain in depressed patients: A systematic review. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:495–505. doi: 10.1002/da.21951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burke WJ, Gergel I, Bose A. Fixed dose trial of the single isomer SSRI escitalopram in depressed outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:331–6. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wade A, Michael Lemming O, Bang Hedegaard K. Escitalopram 10 mg/day is effective and well tolerated in a placebo-controlled study in depression in primary care. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;17:95–102. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200205000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lepola UM, Loft H, Reines EH. Escitalopram (10-20 mg/day) is effective and well tolerated in a placebo-controlled study in depression in primary care. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;18:211–7. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200307000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudolph RL, Feiger AD. A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trialof once daily venlafaxine extended release (XR) and fluoxetine for the treatment of depression. J Affect Disord. 1999;56:171–81. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thase ME. Efficacy and tolerability of once- daily venfaxine extended release (XR) in outpatients with major depression. The Venlafaxine XR 209 Study Group. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:393–8. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]