Abstract

Drug-induced acute pancreatitis (AP) is under-reported, and a large number of drugs are listed as offenders, but are often overlooked. Knowledge about the possible association of medications in causing AP is important, and needs a high index of suspicion, especially with drugs that have been reported to be the etiology only rarely. Dapsone, a commonly used drug, can cause various hypersensitivity reactions including AP collectively called “dapsone syndrome.” Here, we report dapsone-induced AP in a young man. Our case shows certain dissimilarities like associated acute renal failure and acute hemolysis not previously described.

KEY WORDS: Acute pancreatitis, acute renal failure, adverse drug reactions, dapsone syndrome, drug-induced pancreatitis

Introduction

The incidence of drug-induced pancreatitis is ~2% in the general population.[1] Drug-induced acute pancreatitis (AP) is implicated in only a minority of cases. They usually occur acutely with a variable mild to fatal course. WHO database lists 525 different drugs, which can cause AP. An Australian study showed that routinely used drugs accounted for 3.4% in 328 AP cases.[2] The pathophysiology suggested include pancreatic duct constriction, immunosuppression, cytotoxic, osmotic pressure, metabolic effects, arteriolar thrombosis, direct cellular toxicity, and hepatic involvement. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome, a serious condition, has been reported in association with various drugs including dapsone. Dapsone (4-4’- diaminodiphenylsulfone) is used since over 50 years in leprosy, Pneumocystis carini pneumonia and other dermatological conditions. Here, we report a young man who presented with AP-induced by dapsone therapy with clinical presentations that had certain dissimilarities with those reported in literature earlier.

Case Report

A 31-year-old nondiabetic, nonhypertensive, nonalcoholic man presented with acute abdominal pain and vomiting for 2 days associated with mild fever, anorexia, icterus, and melena, skin rash over his back and trunk. He was under treatment with oral dapsone 100 mg for pemphigus for 3 months. He had jaundice 8 years ago and upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGI) bleed 4 years back. He was icteric, anemic and oliguric. His blood pressure was 110/78 mm Hg. The upper abdomen was tender. There was no hepatosplenomegaly, edema, ascites, or palpable peripheral lymph nodes.

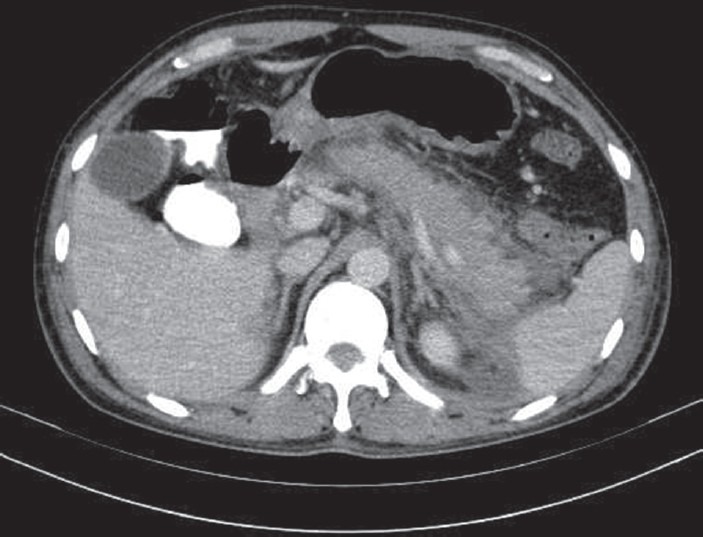

Laboratory examination showed hemoglobin 4.9 g/dl, white blood cell 15,800/dl (neutrophil 77% and eosinophil 02%), reticulocyte 17%, platelet 140,000/dl, serum creatinine 12.4 mg/dl, and urea 184.4 mg/dl. Liver function test showed serum bilirubin 5.68 mg/dl (unconjugated 5.13 mg/dl), aspartate aminotransferase 49 U/L. Alanine aminotransferase 52 U/L. Serum albumin 3.3 g/dl, gamma-glutamyltranferase 25 U/L and alkaline phosphatase 89 U/L, serum amylase 270 U/L (0-80 U/L), serum lipase 314.8 U/L (13-60 U/L) and serum lactate dehydrogenase 1061.7 (25-450) IU/L. Viral hepatitis markers (A, B, C, and E), HIV I, HIV II, antinuclear antibodies Hep-2, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), peripheral-ANCA and cytoplasmic-ANCA were negative. Serum IgG4 was 2.02 (0.03-2) g/l. Ultrasonography abdomen showed increased bilateral kidney size with the loss of corticomedullary differentiation (right kidney 11 × 6 cm and left kidney 11 × 6.5 cm), ascites, bilateral minimal pleural effusion and a bulky tail of pancreas. A plain computed tomography (CT) scan of abdomen 2 days later reported the same [Figure1], with normal pancreatic ductal system. UGI endoscopy revealed an active anterior wall duodenal ulcer. Dapsone was stopped. He was treated as a case of AP with duodenal ulcer bleed with acute renal failure (ARF) and hemolytic anemia (HA).

Figure 1.

Plain computed tomography scan of abdomen showing mild pancreatitis with minimal ascites

He recieved eight units of blood transfusion and four sittings of hemodialysis were carried out. He had two episodes of generalized convulsion, which was controlled with phenytoin. At discharge after 1 month, his renal functions, hemogram and serum amylase and lipase were normal. Re-evaluation after 1 month revealed no clinical or imaging abnormalities.

Discussion

Acute pancreatitis due to drug reactions is often overlooked because of the difficulty appreciating a drug as its cause. Classically, adverse reactions to dapsone (dapsone syndrome) can occur abruptly after dapsone therapy as a hypersensitivity reaction within 3-6 weeks, consisting of fever, exfoliative dermatitis, lymphadenopathy, lymphocytosis, methemoglobinemia, HA and hepatitis, with a frequency of 0.2-0.5%, respectively.[3]

Our patient had clinicobiochemical and radio-imaging features compatible with AP, without hepatitis (normal transaminases), although dapsone heptotoxicity is common. Significant features in our case were a severe HA with jaundice and ARF. Oxidant hemolysis is a known complication of dapsone, probably mediated by cytochrome P-450 induced metabolism of dapsone to hydroxylamines. It can occur irrespective of G-6-PD deficiency, and can be life threatening if associated with the latter. HA due to dapsone is aggravated by renal failure and may explain the rapid onset of the acute severe anemia in our case.

In view of the very short duration and hemodynamically stable state of the patient on admission, the azotemia was unlikely to be prerenal. The melena was a later development, possibly due to stress induced reactivation of chronic duodenal ulcer, as he had a past history of UGI bleed. Our case represents an incomplete form of classical dapsone syndrome as lymphadenopathy, lymphocytosis, hepatitis and methemoglobinemia were absent. Incomplete dapsone syndrome has been reported earlier.

A cause-effect relationship is generally accepted when symptoms reappear upon re-challenge. It was not attempted because of the stormy course in our patient. Medications implicated in AP are classified based on the strength of evidence into one of three classes of drugs associated with AP. Dapsone fulfills the criteria of a Class I A drug causing AP which describes “medications with at least one documented case-report following re-exposure, after excluding other causes”[4] and AP by positive rechallenge of dapsone has been reported earlier in the literature.[5] Serum amylase level more than 5 times the upper level of normal is found in gallstones or drug-induced pancreatitis, but our patient did not have any gallstones/sludge on imaging. Even when AP is induced as an adverse drug event the disease is usually mild or subclinical which was not the case here. Glasgow criteria stratified our case as a severe AP that has a high mortality, where multiorgan failure (the most important indicators of severity) is usually an immediate cause of death mainly due to hepatic and renal failure. Our case had both and despite presenting after 2 days, he responded rapidly after stopping dapsone. All these suggested that dapsone caused the AP in our case. A score of seven (probable) on Naranjos algorithm and the WHO causality showed a probable causality for the adverse drug reaction and dapsone.

Isolated mild ARF associated with dapsone therapy has been described.[6] Our case had severe ARF. This unusual feature has not been previously reported. The implications of the marginally high levels of IgG4 (IgG4 related sclerosing disease, which may involve other systems, including the kidneys) in our patient are not known since pancreatic biopsy was not carried out. Autoimmune pancreatitis was unlikely, in view of the age of patient, an absent history of painless fluctuating jaundice, negative auto-antibodies and negative CT features (irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct). Whether IgG4 predisposed our patient to ARF, in the absence of significant hemodynamic unstability in some unknown way needs exploration in the future.

Other unusual features in our case include the relatively longer time interval to develop the hypersensitivity reactions after starting dapsone (3 months) than mentioned in earlier reports (3-6 weeks). Dapsone used in the multi-drug therapy regime in 51% of 194 leprosy patients developed HA; with 48 (24.7%) within the first 3 months.[7] Therefore, dapsone reactions can occur later than 6 weeks.

Atypical drug-induced AP needs a high index of suspicion, particularly in those without other risk factors of AP. Diagnosis are difficult as a causal relationship needs fulfillment of stringent criteria. Knowledge about the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms as well as evidence for a direct causality remains inadequate. Our case demonstrates that dapsone syndrome can occur in an incomplete form and can be life-threatening unless recognized early.

Conclusion

Dapsone causes hypersensitivity reactions including AP, but is a rare cause of hepatitis, anemia, and other organ dysfunction including renal failure. Severe renal failure is uncommon as in this case. It implies that incomplete forms of this syndrome can occur as illustrated here.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No

References

- 1.Nitsche CJ, Jamieson N, Lerch MM, Mayerle JV. Drug induced pancreatitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:143–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barreto SG, Tiong L, Williams R. Drug-induced acute pancreatitis in a cohort of 328 patients. A single-centre experience from Australia. JOP. 2011;12:581–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coleman MD. Dapsone toxicity: Some current perspectives. Gen Pharmacol. 1995;26:1461–7. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(95)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jha SH, Reddy JA, Dave JK. Dapsone-induced acute pancreatitis. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37:1438–40. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bank S, Indaram A. Causes of acute and recurrent pancreatitis. Clinical considerations and clues to diagnosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1999;28:571–89. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70074-1. viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alves-Rodrigues EN, Ribeiro LC, Silva MD, Takiuchi A, Fontes CJ. Dapsone syndrome with acute renal failure during leprosy treatment: Case report. Braz J Infect Dis. 2005;9:84–6. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702005000100014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deps P, Guerra P, Nasser S, Simon M. Hemolytic anemia in patients receiving daily dapsone for the treatment of leprosy. Lepr Rev. 2012;83:305–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]