Abstract

Aim

To compare the functional and radiographic results of dynamic hip screw (DHS) and expandable proximal femoral nail (EPFN) in the treatment of extracapsular hip fractures.

Methods

A randomized controlled trial of sixty hip fracture patients. Outcomes included mortality, residency, independence, mobility, function and radiographic results at a minimum of 1 year.

Results

Twenty-nine EPFN patients demonstrated fewer cases of shaft medialization or femoral offset shortening compared to the 31 DHS patients. Mortality, complications and functional outcomes were similar.

Conclusion

EPFN provides stable fixation of pertrochanteric hip fractures and prevents neck shortening that is commonly observed after DHS fixation.

Keywords: Hip fracture, Dynamic hip screw, Proximal femoral nail, Offset, Expandable

1. Introduction

Pertrochanteric fractures of the proximal femur are very common among the elderly. The incidence of these fractures is expected to rise even further with advancing age of the population. These fractures lead to high rates of mortality, morbidity and loss of independence.1,2 The goal of treatment of these fractures is to achieve rigid fixation and to allow early mobilization and weight bearing in order to prevent morbidity and to facilitate rehabilitation.3 Pertrochanteric hip fractures have been treated successfully with dynamic hip screw (DHS) implants that allow controlled compression at the fracture site.3–6 Alternatively, these fractures can be treated using proximal femoral nails (PFN), usually inserted percutaneously and associated with decreased blood loss, less exposure to radiation and lower blood transfusion requirements.4,7,8 PFNs also provide greater stability due to their short moment arm and their buttress effect prevents medialization of the femoral shaft.6 However, complications associated with their use include mainly femur fractures, cut outs through the femoral head, and the need for reoperations.6,7,9–14 PFNs have only been proven superior in the very unstable subtrochanteric and reverse oblique fractures (OTA/ASIF 31A3) and these implants are more expansive when compared to DHS.9

The expandable PFN (EPFN) [Fig. 1] uses a hydraulic expansion mechanism and allows good purchase of both femoral shaft and head without need for reaming or distal locking.8,15,16 It therefore provides the biomechanical advantages of a PFN with a potential for reduced cutouts and associated fractures.

Fig. 1.

Expendable proximal femoral nail system.

This study was designed to assess whether surgical treatment with EPFN is superior to DHS in terms of malunion and functional outcome following pertrochanteric hip fractures. We chose to compare this implant to the most common treatment choice (DHS) in order to demonstrate its potential mechanical benefits.

2. Materials and methods

Between June 2008 and February 2010, we randomized patients who had a unilateral extracapsular (OTA/ASIF 31A1 and 31A2) hip fracture following low-energy trauma to surgical treatment with either a DHS (CHS; Smith & Nephew, Warwick, UK) or an EPFN (Fixion; HMB Medical Technologies, Herzliya, Israel). Exclusion criteria were age below 60 years, pathologic fractures, patients with a life-threatening disease (ASA score ≥4), subtrochanteric or reverse oblique fracture patterns (OTA/ASIF 31A3), inability to give informed consent due to dementia or confusional state, and previous fracture or previous surgery of the affected leg. The study was approved by the institutional review board and informed consent was obtained from all patients before surgery.

AO/ASIF fracture classification was determined by three independent investigators based on pelvic anteroposterior (AP) and axial hip radiographs. Randomization was done by sealed envelopes that were prepared in advance using a computer-generated randomized list and concealment was strictly maintained. Each patient's background data were collected on admission, and included age, gender, laterality of the fracture, comorbidities (specifically, ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, history of cerebrovascular accident, chronic renal failure, atrial fibrillation, Parkinson's disease and dementia), pharmacological treatment, smoking status, ASA score,17 residency (living in own home, nursing home or institution), social function and independence status [using Jensen's classification]18 and mobility [using Parker and Palmer's scoring system].19

Surgery was performed on the first available operative day following optimization of the patient's medical state. The patient was operated while lying in the supine position on a fracture table, and the procedure was carried out under fluoroscopic guidance. Closed reduction was attempted in all cases, and open reduction was performed when satisfactory fracture alignment could not be achieved in a closed fashion. All patients received intravenous antibiotics immediately before surgery and low-molecular-weight heparin for 6 weeks after it. The DHS was introduced through a vastus lateralis split approach. A 135° plate was used and 3 diaphyseal screws were inserted in all cases. The femoral head screw was inserted in a central–central or a central-inferior position, and a tip apex distance of less than 25 mm was achieved in all cases. The EPFN [Fig. 1] was introduced via a percutaneous trochanteric approach. It was inserted at the medial tip of the greater trochanter without reaming of the femoral canal. Either a 10 mm or a 12 mm nail with a 130° nail-peg angle was used, and the EPFN was inflated to a maximum of 70 mmHg and expanded to a maximum of 16 mm or 19 mm, respectively. The nail height was then determined under fluoroscopy and an eight mm hole was drilled into the femoral head at a 130° angle to the nail using the lateral handle sleeve. Femoral head peg was inserted via percutaneous approach and inflated to 100–140 mmHg, followed by locking of the nail-peg interface. The recorded intraoperative parameters included the time from trauma to surgery, length of operation time, amount of exposure to radiation, type of implant used and any complication or technical difficulty.

Following surgery, all patients were allowed weight bearing as tolerated and all were encouraged to begin walking with a frame on the first postoperative day. Rehabilitation protocol was the same for all patients, regardless of the type of implant used. The drop in blood hemoglobin concentration, amount of blood transfused, length of hospital stay and any postoperative complications were recorded. Patients were discharged either to their own home or to a rehabilitation facility.

Follow up was performed at 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 3 months, 6 months and 1 year at the outpatient clinic. The physical examination at each visit included measurement of leg length discrepancy (LLD), wound healing, range of motion of both hips, mobility assessment using the Parker and Palmer score, and radiographic evaluation with standard pelvic and hip AP and axial views. The Harris Hip Score (HHS),20 independence (Jensen's) and mobility (Parker & Palmer's) scores, and residency status were used to evaluate functional status at the last follow up visit. Patients who did not attend the clinic for their follow up visit were visited by one of the investigators at their home.

Radiographs were assessed and analyzed by three independent investigators. The immediate postoperative reduction was classified as anatomic (cortical continuity, symmetrical neck shaft angle, no shortening), good or poor (>10 degrees of varus or valgus compared to the contralateral side and/or >10 mm of shortening). Last follow up radiographs were assessed for leg length discrepancy (based on vertical distance from femoral head to lesser trochanter), bilateral femoral offset (based on horizontal distance from femoral head to tip of greater trochanter), bilateral neck shaft angle, femoral shaft medialization and heterotopic ossification. Malunion was defined when there was >10 degrees of varus or valgus and >10 mm of shortening. All distance measurements were adjusted to an assumed magnification of 115%.

2.1. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared using Student's T-test and parametric variables were compared using the Chi-square test. Dichotomous outcomes were compared using Fisher's exact test. The univariate analysis was repeated after separation to groups based on fracture pattern. Logistic regression was used for detection of significant contributors to the independent variables: malunion, poor HHS score and poor Parker score.

3. Results

A total of 112 patients met the inclusion criteria during the study period, and 60 of them agreed to participate in the study. Following group allocation, 31 patients were treated with a DHS and 29 with an EPFN. The two treatment groups were comparable in selected features before the fracture occurred (Table 1). The only significant difference between the groups was in the level of hemoglobin on admission.

Table 1.

Pre-fracture variables in 60 patients with intertrochanteric fractures treated with dynamic hip screws (DHSs) and expandable proximal femoral nails (EPFNs).

| Variable | Total N = 60 | DHSs N = 31 | EPFNs N = 29 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 83.1 ± 6.17 (66–97) | 83.1 ± 6.7 (66–97) | 83.1 ± 5.7 (69–94) |

| Gender (male) | 14 (23%) | 8 (26%) | 6 (21%) |

| Body mass index | 25.2 ± 4.7 (16–39) | 25.5 ± 4.7 (16–38.6) | 24.9 ± 4.8 (16–39) |

| Heart disease | 14 (23%) | 7 (23%) | 7 (24%) |

| Diabetes | 14 (23%) | 6 (19%) | 8 (28%) |

| Renal failure | 7 (12%) | 3 (10%) | 4 (14%) |

| Parkinson's disease | 2 (3%) | 2 (6%) | 0 |

| Dementia | 9 (15%) | 3 (10%) | 6 (21%) |

| Hemoglobin level on admission (g/dL)∗ | 11.9 ± 1.46 (7.9–15.2) | 11.5 ± 1.6 (7.9–15.2) | 12.3 ± 1.1 (8.9–15.2) |

| Residence | |||

| Own home | 49 (82%) | 25 (81%) | 24 (83%) |

| Nursing institution | 11 (18%) | 6 (19%) | 5 (17%) |

| Independencea | 2.42 ± 1.15 | 2.39 ± 1.17 | 2.45 ± 1.15 |

| Ambulation scoreb | 6.17 ± 2.67 | 6 ± 2.73 | 6.34 ± 2.64 |

| ASA scorec | 2.28 ± 0.58 | 2.26 ± 0.63 | 2.31 ± 0.54 |

| Fracture type | |||

| 31A1 | 20 (33%) | 10 (32%) | 10 (34%) |

| 31A2 | 40 (67%) | 21 (68%) | 19 (66%) |

| Laterality | |||

| Right | 36 (60%) | 16 (52%) | 20 (69%) |

| Left | 24 (40%) | 15 (48%) | 9 (31%) |

| Time from fall to surgery (hours) | 50 ± 30 (4–168) | 55 ± 35 (4–168) | 45 ± 25 (19–133) |

The mean operative time was 60 ± 25 min (range 27–157), and the mean exposure to radiation was 57 ± 36 s. Blood transfusions were required more often among patients treated with the DHS (1.29 ± 1.47 compared with 0.72 ± 0.92 units of packed cells per patient treated with the EPFN, p = 0.08), and the surgical incision was longer among DHS patients (12.2 ± 2.5 cm compared with 10.5 ± 2.8 cm for EPFN patients, p = 0.02). The quality of reduction on the first postoperative radiograph was similar for both groups (16% poor reduction for DHS compared with 14% poor reduction for EPFN, p = 0.65) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Intraoperative and early postoperative outcomes of 60 patients treated with dynamic hip screws (DHSs) and expandable proximal femoral nails (EPFNs).

| Variable | Total N = 60 | DHSs N = 31 | EPFNs N = 29 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anesthesia | |||

| Spinal | 15 (25%) | 8 (26%) | 7 (24%) |

| General | 45 (75%) | 23 (74%) | 22 (76%) |

| Operation time (min) | 59.4 ± 24.6 (27–157) | 64 ± 26 (30–157) | 54.5 ± 22.5 (27–120) |

| Radiation time (s) | 57.1 ± 36 (16–210) | 50.9 ± 25.4 (18–130) | 63.5 ± 44 (16–210) |

| Scar length (cm)∗ | 11.3 ± 2.8 (6–20) | 12.2 ± 2.5 (8–17) | 10.5 ± 2.8 (6–20) |

| Quality of reduction | |||

| Anatomic | 25 (42%) | 11 (36%) | 14 (48%) |

| Good | 26 (43%) | 15 (48%) | 11 (38%) |

| Poor | 9 (15%) | 5 (16%) | 4 (14%) |

| Intraoperative fracture | 4 (7%) | 3 (9%) | 1 (3%) |

| Femoral shaft | 1 (2%) | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| Subtrochanteric | 1 (2%) | 1 (3%) | 0 |

| Greater trochanter | 2 (3%) | 2 (6%) | 0 |

| Complications | |||

| 30-day mortality | 1 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 2 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 2 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) |

| Wound discharge | 11 (18%) | 7 (23%) | 4 (14%) |

| Hospitalization (days) | 10.9 ± 6.1 (5–46) | 10.1 ± 4.4 (5–26) | 11.7 ± 7.5 (6–46) |

∗p < 0.05.

4. Complications

Four iatrogenic fractures occurred intraoperatively. Three patients in the DHS group had a fracture line through the nail drill hole, transforming the fracture into a subtrochanteric fracture. In all three cases the fixation was estimated to be stable and operative as well as postoperative treatment was not changed. One EPFN patient had a femoral shaft longitudinal crack upon nail expansion that was detected with the fluoroscopy and estimated to be stable by the surgeons [Fig. 2]. This fracture was treated with partial weight bearing for 6 weeks, followed by uncomplicated rehabilitation. Detailed intraoperative and early postoperative outcomes are given in Table 2.

Fig. 2.

Lateral X-ray view of femur following insertion of EPFN demonstrating longitudinal crack (arrow).

Postoperative complication rates were similar in both treatment groups. One DHS patient died of a complicated perforated duodenal ulcer during her hospitalization. Seven other patients died during the follow up period (not included in the analysis of functional and radiographic outcome), and one patient was lost to follow up after three months (the analysis of her data was based on her last follow up visit). The other 51 patients were followed for a minimum of 1 year and were included in the analysis. There was one case of femoral head cut out following DHS involving a patient who consequently underwent a revision surgery and whose fracture successfully united thereafter. Another DHS patient had a femoral shaft fracture distal to the DHS after a fall and was reoperated by means of a retrograde IMN and a third DHS patient had delayed union, had then broken the plate and screws and finally varus malunion. A reoperation was also performed following an EPFN procedure because of dislodgement of the peg from the nail. The peg had not been locked to the nail as a result of a surgeon's error and the patient was reoperated using the same nailing system resulting in fracture union. These complications were observed in patients with 31A2 fractures. Another EPFN patient had wound infection that was treated with oral antibiotics. There were two cases of pulmonary embolism in the EPFN group, and one case of deep vein thrombosis in the DHS group.

5. Functional outcome

There were no significant differences between the groups in change of residency or independence. Patients in the EPFN group had better functional results in the HHS score (67 ± 15 vs 63 ± 16, non-significant). HHS support subscore was significantly better among EPFN patients (6.4 ± 3.7 for EPFN compared with 4.3 ± 3.5 for DHS, p < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Complications and functional outcomes at 1 year follow up of 60 patients treated with dynamic hip screws (DHSs) and expandable proximal femoral nails (EPFNs).

| Variable | Total N = 52 | DHSs N = 26 | EPFNs N = 26 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cut out | 1 (2%) | 1 (3%) | 0 |

| Periprosthetic fracture | 1 (2%) | 1 (3%) | 0 |

| Malunion | 11 (18%) | 6 (19%) | 5 (17%) |

| Reoperation | 2 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) |

| Plate/screw failure | 1 (2%) | 1 (3%) | 0 |

| Residence | |||

| Own home | 39 (75%) | 19 (73%) | 20 (77%) |

| Nursing | 6 (12%) | 4 (15%) | 2 (8%) |

| Institution | 7 (13%) | 3 (12%) | 4 (15%) |

| Change of residence | 7 (13%) | 3 (12%) | 4 (15%) |

| Independencea | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 3.1 ± 1.1 | 2.7 ± 1.1 |

| Change of independence | 36 (60%) | 20 (65%) | 16 (55%) |

| Ambulation scoreb | 4.2 ± 2.9 | 4.1 ± 2.6 | 4.3 ± 3.1 |

| Decrease in ambulation score | 33 (55%) | 18 (58%) | 15 (52%) |

| Harris Hip Scorec | |||

| Pain (0–44) | 36 ± 9 | 35.9 ± 7.9 | 36.1 ± 10.1 |

| Support (0–11)∗ | 5.3 ± 3.7 | 4.3 ± 3.5 | 6.4 ± 3.7 |

| Distance (0–11) | 5.7 ± 3.5 | 5.2 ± 3.5 | 6.1 ± 3.5 |

| Limp (0–11) | 5.4 ± 3.7 | 5.4 ± 3.5 | 5.4 ± 4 |

| Total (0–100) | 65 ± 15.5 | 63 ± 16 | 67 ± 15 |

6. Radiographic outcome

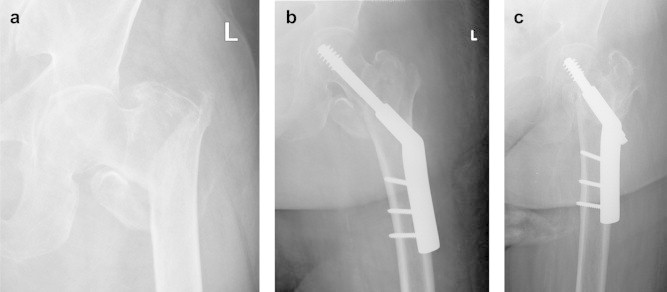

The radiographic assessment showed that patients treated with DHS had significantly shorter femoral offset (compared to the unaffected side) than those treated with an EPFN (3.4 ± 5.2 mm in DHS compared to 0.22 ± 1.4 mm in EPFN, p < 0.01)). Shortening of the femur measured 3.2 ± 4.8 mm and was similar in both treatment groups. Nine DHS patients (35%) had femoral shaft medialization compared to only one (4%) EPFN patient (p < 0.05). Thirteen (50%) DHS patients had heterotopic ossification compared to six (23%) EPFN patients (p = 0.089). Overall, there were 7 (13%) cases of malunion with no significant differences between the two groups. Table 4 details the radiographic outcomes. Among patients with partially unstable fractures (AO 31A2) those treated with DHS had a shorter femoral offset (compared to the unaffected side) (5.3 ± 5.7 mm compared to 0.25 ± 1.7, p < 0.001), similar femoral shortening, greater femoral shaft medialization (38% versus 6%, p < 0.05) and more heterotopic ossification (63% versus 25%, p < 0.05) when compared to EPFN patients [Figs. 3 and 4]. No significant differences were found between DHS and EPFN patients with stable (31A1) fractures. Specifically, two of these 31A2 fractures fixed with a DHS were noted to have severely collapsed into varus and malunion during the early follow up period.

Table 4.

Radiographic outcomes of patients treated with dynamic hip screws (DHSs) and expandable proximal femoral nails (EPFNs).

| Outcome | Total N = 52 | DHSs N = 26 | EPFNs N = 26 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Femur shortening (mm) | 3.5 ± 6.2 (0–36) | 3.2 ± 7.8 (0–36) | 3.7 ± 4.3 (0–16) |

| Reduced offset (mm)∗ | 2.7 ± 6 (max 18) | 6.2 ± 6.4 (max 18) | 0.8 ± 2.6 (max 7) |

| Shaft medialization∗ | 10 (19%) | 9 (36%) | 1 (4%) |

| Heterotopic ossification | 19 (37%) | 13 (52%) | 6 (22%) |

| Malunion | 11 (21%) | 6 (24%) | 5 (19%) |

∗p < 0.05.

Fig. 3.

AP X-ray views of left proximal femur demonstrating (a) an unstable (31A2) intertrochanteric fracture treated with (b) an EPFN and maintaining postoperative (c) reduction at union.

Fig. 4.

AP X-ray views of left proximal Femur demonstrating (a) an unstable (31A2) intertrochanteric fracture treated with (b) a DHS, restoring proximal femur anatomy, but with (c) shortening of femoral neck and reduced femoral offset at union.

The logistic regression analysis found malunion to be related to old age (p = 0.013) and poor independence (Jensen's) score (p = 0.07), while HHS was found to be mainly affected by the quality of reduction (p = 0.07) and the preinjury mobility (Parker & Palmer's) score (p = 0.026).

7. Discussion

We compared the outcome of two surgical approaches, EPFN with DHS, in order to determine whether the potential biomechanical advantages of the EPFN provide improved radiographic and clinical outcomes following pertrochanteric hip fracture. Our results showed similar rates of mortality, complications and functional outcome, and the treatment with EPFN was associated with better radiographic outcomes, mainly preservation of femoral offset.

DHSs have been widely used throughout the past few decades for the treatment of pertrochanteric hip fractures. These implants allow controlled impaction at the fracture site and reduce the chance of femoral head cut out. They are reliable and predictable, but the controlled impaction often leads to malunion with varus collapse and femoral neck shortening.3,11 PFNs were introduced in the 1990's and they were proven to be very effective in the treatment of subtrochanteric and reverse oblique fractures. PFNs were also used for internal fixation of pertrochanteric fractures, but with contradictory results.2,9,11,12 The main problem with PFNs is the suboptimal purchase in the femoral head and the subsequent cut out, probably due to varus deviation and head/neck rotation.21 Different PFN designs including the Gamma nail (Howmedica International, England) later followed by the trochanteric gamma nail (TGN), and the PFN (Synthes-Stratec, Switzerland) with its additional antirotation screw, followed by the PFNa, with its antirotation helical blade and smaller distal diameter to prevent shaft fractures all showed advantages in terms of shorter incisions, shorter operative time, shorter exposure to fluoroscopy and decreased blood loss but were also associated with cut outs and femur fractures2,7,9,11,13,14,22–25 and failed to provide superior results when compared with the traditional DHS.5,9

Several meta analyses have looked into the advantages or disadvantages of PFNs compared with DHS in the treatment of proximal hip fractures, and they all concluded that the advantages of PFNs are significant only in the very unstable fractures, hence subtrochanteric (AO/ASIF 31A3). Nevertheless, some PFNs are associated with increased complications such as iatrogenic fractures.6,9,12,22 Also, no single PFN design was found to be superior to others.10,26,27

The Fixion nail is a hydraulically inflated expandable nail. It does not require reaming of the femoral canal and after it is positioned in the medullary canal, the system is inflated with saline through a unidirectional valve using a manual pump. The nail is 220 mm long and 10 or 12 mm wide, and is capable of expansion up to 16 or 19 mm, respectively.8,15 An expandable 8-mm wide peg is inserted through the nail and expanded by means of the same technology. The use of expandable nails was proven effective in the treatment of diaphyseal as well as proximal femur fractures, with no need for further locking.8,15 The expandable peg was found to have favorable biomechanical properties and good purchase of trabecular bone in the femoral head.28 Compared with other nail designs, the EPFN has the potential advantage of avoiding point pressure on the femur shaft and thus reducing the incidence of femoral shaft fractures. Also, the design of the peg with the associated condensation of spongy bone around it following expansion provides good purchase of the head and can help to prevent cut out.16 The use of EPFNs in diaphyseal femoral and tibial fractures, however, was associated with iatrogenic fracture progression.29

We found the EPFN to be effective in the fixation of pertrochanteric fractures. The complication rate in the current study was low with no femoral head cutouts, maybe due to its good purchase of the femoral head. One case of reoperation due to surgical error in locking the peg-nail and one case of fracture progression following insertion and inflation of the nail were recorded. The radiographic outcome was superior to that achieved with DHS, mainly in terms of shaft medialization and preservation of femoral offset. The reason for this is probably that the DHS does not maintain the reduction but allows compression at the fracture site. Pajarinen et al also found increased shaft medialization, reduced offset and femoral neck shortening with DHS treatment compared to PFN treatment.23 Notably, the mortality, residence, independence and functional scores did not differ significantly between our two study groups. There was a trend toward improved mobility and functional outcome among patients treated with EPFN, but the small number of patients does not allow sufficient power to confirm this result. Parker et al randomized 600 hip fractures to be treated either with a sliding hip screw or with a Targon PF nail and found improved mobility among those treated with the nail at the 1 year follow up.30 We believe that maintenance of fracture reduction as well as the minimally invasive technique of application contributed to improved biomechanics of the operated proximal femur and laid the foundation for successful rehabilitation and restoration of independent ambulation following EPFN insertion. Larger cohorts are required in order to study if this result is also associated with improved ambulation as seen in this study.

The main limitation of this study is the small number of patients, and the resultant lack of power to detect differences in outcomes between groups. Radiographic measurements are subjected to error due to suboptimal control of hip rotation. However, this data may be included in future meta-analysis to improve the statistical power.

We conclude that the EPFN is a promising technology for the treatment of pertrochanteric fractures, allowing for good and stable fixation and maintenance of reduction until fracture union. The EPFN seems to be associated with low rates of cut out and fractures distal to the nail tip. Fracture progression is a possible complication, and surgeons should inflate the EPFN under fluoroscopic control. Further studies are needed to determine the applicability of this technology in larger populations and in focus on specific fracture patterns.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Lenich A., Vester H., Nerlich M. Clinical comparison of the second and third generation of intramedullary devices for trochanteric fractures of the hip-blade vs screw. Injury. 2010 Dec;41:1292–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.07.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saudan M., Lübbeke A., Sadowski C. Pertrochanteric fractures: is there an advantage to an intramedullary nail?: a randomized, prospective study of 206 patients comparing the dynamic hip screw and proximal femoral nail. J Orthop Trauma. 2002 Jul;16:386–393. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pajarinen J., Lindahl J., Michelsson O. Pertrochanteric femoral fractures treated with a dynamic hip screw or a proximal femoral nail. A randomised study comparing post-operative rehabilitation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005 Jan;87:76–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zou J., Xu Y., Yang H. A comparison of proximal femoral nail antirotation and dynamic hip screw devices in trochanteric fractures. J Int Med Res. 2009 Jul-Aug;37:1057–1064. doi: 10.1177/147323000903700410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barton T.M., Gleeson R., Topliss C. A comparison of the long gamma nail with the sliding hip screw for the treatment of AO/OTA 31-A2 fractures of the proximal part of the femur: a prospective randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010 Apr;92:792–798. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gadegone W.M., Salphale Y.S. Proximal femoral nail – an analysis of 100 cases of proximal femoral fractures with an average follow up of 1 year. Int Orthop. 2007 Jun;31:403–408. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0170-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Utrilla A.L., Reig J.S., Muñoz F.M. Trochanteric gamma nail and compression hip screw for trochanteric fractures: a randomized, prospective, comparative study in 210 elderly patients with a new design of the gamma nail. J Orthop Trauma. 2005 Apr;19:229–233. doi: 10.1097/01.bot.0000151819.95075.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folman Y., Ron N., Shabat S. Peritrochanteric fractures treated with the Fixion expandable proximal femoral nail: technical note and report of early results. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2006 Apr;126:211–214. doi: 10.1007/s00402-006-0110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker M.J., Handoll H.H. Gamma and other cephalocondylic intramedullary nails versus extramedullary implants for extracapsular hip fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Sep 8;9:CD000093. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000093.pub5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrera A., Domingo L.J., Calvo A. A comparative study of trochanteric fractures treated with the gamma nail or the proximal femoral nail. Int Orthop. 2002;26:365–369. doi: 10.1007/s00264-002-0389-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menezes D.F., Gamulin A., Noesberger B. Is the proximal femoral nail a suitable implant for treatment of all trochanteric fractures? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005 Oct;439:221–227. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000176448.00020.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones H.W., Johnston P., Parker M. Are short femoral nails superior to the sliding hip screw? A meta-analysis of 24 studies involving 3,279 fractures. Int Orthop. 2006 Apr;30:69–78. doi: 10.1007/s00264-005-0028-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ekström W., Karlsson-Thur C., Larsson S. Functional outcome in treatment of unstable trochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures with the proximal femoral nail and the Medoff sliding plate. J Orthop Trauma. 2007 Jan;21:18–25. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31802b41cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leung K.S., So W.S., Shen W.Y. Gamma nails and dynamic hip screws for peritrochanteric fractures. A randomised prospective study in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992 May;74:345–351. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B3.1587874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lepore L., Lepore S., Maffulli N. Intramedullary nailing of the femur with an inflatable self-locking nail: comparison with locked nailing. J Orthop Sci. 2003;8:796–801. doi: 10.1007/s00776-003-0709-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinberg E.L., Sternheim A., Blachar A. Femoral head density on CT scans of patients following hip fracture fixation by expandable proximal peg or dynamic screw. Injury. 2010 Jun;41:647–651. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foss N.B., Kehlet H., American Society of Anesthesiologists New classification of physical status. Anesthesiology 1963, cited in: hidden blood loss after surgery for hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:1053–1059. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B8.17534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen J.S. Determining factors for mortality following hip fractures. Injury. 1984;15:411–414. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(84)90209-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker M.J., Palmer C.R. A new mobility score for predicting mortality after hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:797–798. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B5.8376443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris W.H. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures treatment by mold arthroplasty: an end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51-A:737–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simmermacher R.K., Ljungqvist J., Bail H. The new proximal femoral nail antirotation (PFNA) in daily practice: results of a multicentre clinical study. Injury. 2008 Aug;39:932–939. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bridle S.H., Patel A.D., Bircher M. Fixation of intertrochanteric fractures of the femur. A randomised prospective comparison of the gamma nail and the dynamic hip screw. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991 Mar;73:330–334. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B2.2005167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pajarinen J., Lindahl J., Savolainen V. Femoral shaft medialisation and neck-shaft angle in unstable pertrochanteric femoral fractures. Int Orthop. 2004 Dec;28:347–353. doi: 10.1007/s00264-004-0590-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mereddy P., Kamath S., Ramakrishnan M. The AO/ASIF proximal femoral nail antirotation (PFNA): a new design for the treatment of unstable proximal femoral fractures. Injury. 2009 Apr;40:428–432. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffmann R., Schmidmaier G., Schulz R. Classic nail versus DHS. A prospective randomised study of fixation of trochanteric femur fractures. Unfallchirurgie. 1999 Mar;102:182–190. doi: 10.1007/s001130050391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yaozeng X., Dechun G., Huilin Y. Comparative study of trochanteric fracture treated with the proximal femoral nail anti-rotation and the third generation of gamma nail. Injury. 2010 Jul;41:986–990. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parker M.J., Handoll H.H. Intramedullary nails for extracapsular hip fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Jul 19;3:CD004961. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004961.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blumberg N., Shasha N., Tauber M., Dekel S., Steinberg E. The femoral head expandable peg: improved periimplant bone properties following expansion in a cadaveric model. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2006 Oct;126:526–532. doi: 10.1007/s00402-006-0188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith W.R., Ziran B., Agudelo J.F. Expandable intramedullary nailing for tibial and femoral fractures: a preliminary analysis of perioperative complications. J Orthop Trauma. 2006 May;20:310–314. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200605000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parker M.J., Bowers T.R., Pryor G.A. Sliding hip screw versus the Targon PF nail in the treatment of trochanteric fractures of the hip: a randomised trial of 600 fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012 Mar;94:391–397. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B3.28406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]