Trials of preventive biomedical HIV interventions have yielded promising results;1,2 however, few have enrolled substantial numbers of black men who have sex with men (MSM) and male-to-female transgender women (transwomen) who face the highest HIV incidence, morbidity, and mortality of any ethnic/racial group in the United States.3,4,5 Given that vaccine immunogenicity may vary by race,6,7 failure to enroll a sufficient number of black Americans in HIV vaccine trials may miss a protective vaccine effect when one exists or ascribe benefit when it does not.8,9 Additionally, investigators have documented barriers to participation in trials among blacks including limited awareness of studies, mistrust in clinical research, and concerns about safety and side effects.10-13

One promising recruitment method, long-chain peer referral (LCPR), has been effective in engaging hard-to-reach populations including black MSM for community-based HIV testing initiatives.14,15 LCPR may overcome some barriers to participation in clinical trials, such as lack of awareness and distrust, by using relationships between peers within social networks. Successful LCPR propagates long-chains from initial “seed” participants who recruit peers (Wave 1) who in turn recruit their peers (Wave 2), and so on, until several recruitment waves are established. Beyond simple peer referral, LCPR purports to reach deeper into social networks to persons several steps removed from those directly accessible to researchers. Like respondent-driven sampling (RDS), this is accomplished by limiting the number of referrals per participant to force recruitment into longer chains. Unlike RDS, the primary purpose is recruitment rather than statistically-adjusted population estimates.15 To our knowledge, this approach has not been explored for vaccine trial recruitment. We therefore piloted the feasibility of LCPR to recruit black MSM and transwomen at the San Francisco site of a phase 2B HIV vaccine efficacy trial. 16

We adapted methods described by Heckathorn and others14,15 to initiate chains of referrals by black MSM and transwomen over a 7-month period. In planning and throughout implementation, key informants and focus groups helped assess barriers and motivators to trial participation and guided our pilot recruitment protocol. We identified initial seeds through the key informants and community providers, HIV vaccine trial staff, and members of local community-based organizations working with black MSM and transwomen communities in San Francisco and Alameda counties. Seeds and subsequent participants were trained in answering common questions concerning vaccine trials and where to find more information. Participants completed a social network and demographic survey that assessed whether they knew other black MSM and/or transwomen, their confidence in educating peers about HIV vaccine trials, and their comfort with referring peers.

Participants were given 5-7 referral coupons to distribute to black MSM or black transwomen who met basic eligibility criteria: age 18-50 years, HIV-negative or status unknown, and able to attend study visits at the site for up to 2 years. Our formative discussions with community members highlighted the importance of transparency surrounding vaccine trial eligibility criteria to avoid a sense of exclusion that could result if many prescreened participants were ultimately ineligible.

For participating in the LCPR pilot (known as “The i2 Project”), participants received $25 and $10 for each participant they referred who underwent telephone pre-screening (PSQ) and an in-person clinic appointment to determine their medical and behavioral eligibility. Those undergoing in-person screening for the trial received $20 for that visit. Each person screened was offered the opportunity to recruit 5-7 peers. Unlike potential vaccine trial participants, initial seed participants could be HIV-infected, given their potential to recruit at-risk HIV negative peers.17 Confidentiality was maintained by using study codes to disburse recruitment incentives rather than revealing names of peers successfully referred. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review boards (IRBs) at the University of California, San Francisco, and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

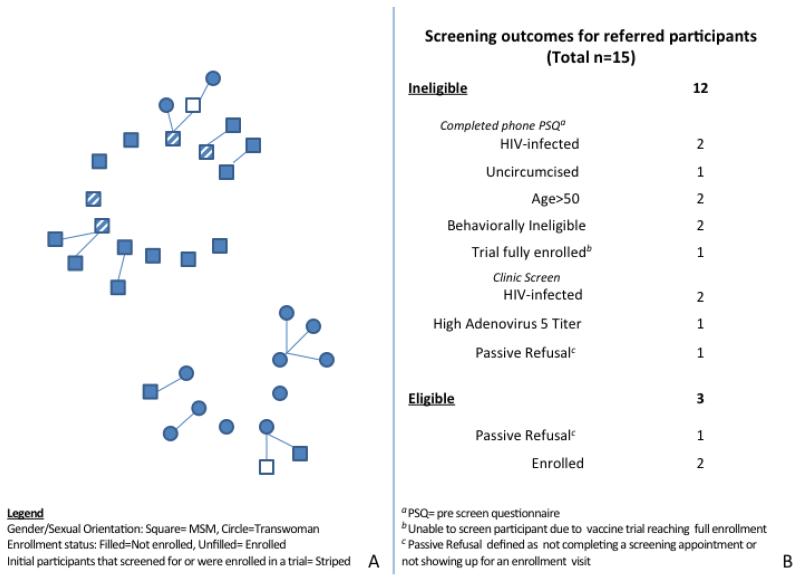

We recruited 17 initial seed participants, 11 of whom were black MSM and 6 of whom were black transwomen. Seven seeds voluntarily self-reported being HIV-positive and four were either currently enrolled in the phase 2b efficacy HIV vaccine trial or had been previously screened for the trial. Fifteen persons (nine black MSM and 6 black transwomen) returned with referral coupons and completed a PSQ (Figure 1). Of those completing the PSQ, 7 were preliminarily eligible for the vaccine study and came to a screening appointment. Of these, 3 were medically eligible and 2 enrolled.

Figure 1.

Outcomes of long-chain peer referral to recruit black MSM and black transwomen for an HIV vaccine efficacy trial (The i2 Project), San Francisco and Alameda counties, California (August 2012-March 2013)

Panel A Recruitment chains among black MSM and black transwomen

Panel B Screening outcomes and reasons for ineligibility among referred participants

The median age of i2 Project participants was 45 years; 65% were unemployed and 71% had at least graduated high school or equivalent. All participants indicated they knew other black MSM and/or transwomen. Participants reported they were confident educating peers about HIV vaccine research and comfortable referring peers to an HIV vaccine trial (mean score 4.5 and 4.8 on a 5-point Likert scale, with 5 representing very confident/comfortable, respectively). Over half (56%) of initial seeds recruited at least one wave of recruits and one seed recruited beyond the first wave. The majority of initial participants who had either participated in an HIV vaccine trial or had screened for one recruited at least one individual in their social network. Of recruits, 2 were HIV-positive but previously unaware of their infection. Other reasons for vaccine trial ineligibility included a detectable antibody titer to adenovirus subtype 5 (the candidate HIV vaccine vector), behavioral ineligibility, age, lack of circumcision, and failure to complete the screening appointment or return for the enrollment visit.

Despite previous success in using LCPR to recruit black MSM into HIV testing campaigns and marginalized populations into cross-sectional surveys,14,15,17 our first effort to apply this strategy to an HIV vaccine trial had limited success. We were able to enlist a large number of seeds drawn from the diversity of black MSM and transwomen in the San Francisco Bay Area. Initial and subsequent participants had a high level of comfort in understanding and communicating HIV vaccine trial concepts. Additionally, seeds were able to tap into an unreached, at-risk population given that 2 of 15 recruits were previously unaware of their HIV-positive status. However, these factors were insufficient to catalyze recruitment chains for the vaccine screening stage beyond a limited number in the first and second waves.

Our quantitative data and qualitative feedback indicate several reasons why LCPR as implemented may not have recruited many black MSM and transwomen. First, the desire to make all vaccine trial eligibility criteria transparent may have led to overly stringent selection of those judged to be eligible and willing by peers. This may have prevented sufficient propagation of recruitment chains widely and deeper into social networks given the high prevalence of HIV infection and persistent stigma about HIV in these communities.18 Second, the incentives, while consistent with other local studies14,17 may have been inadequate, particularly for those travelling from Alameda County. Third, while seeds reported being comfortable recruiting and educating peers, HIV vaccine trials involve multiple complex concepts, such as randomization, double-blinding, placebo control, and side effects, that may be difficult to communicate across multiple peer-recruitment waves. Fourth, exceptional demands of a vaccine trial (e.g., injection of an experimental product, multi-year follow-up) are not changed by the mechanism of peer referral. Finally, we cannot assume that incentivized peer recruitment will necessarily address mistrust of clinical research in communities.

We did find that seeds who either screened for an HIV vaccine trial or had enrolled in one previously were better able to recruit their peers, suggesting that personal experience and better understanding of trial logistics enable persons to more effectively address issues of trust and educate peers. Our study also reinforced findings that HIV-infected persons are able to recruit at-risk HIV-uninfected individuals potentially eligible for vaccine trials.14,17,19

The question remains how to adapt LCPR to encourage black participation in future HIV vaccine efficacy trials. One way forward is to use a staged approach to more widely tap into networks. In the first stage, investigators could encourage initial participants to invite all black MSM and transwomen, regardless of perceived vaccine study eligibility, to participate in research for which a larger proportion would be eligible. Positive experiences in such studies can foster trust, raise awareness of HIV research, increase familiarity with research concepts, and improve comfort with study sites and staff. In the second stage, a cohort of vaccine study eligible individuals can be selected from the larger pool of participants. Individuals with prior trial experience may also serve as community liaisons and peer educators. This staged approach using LCPR worked successfully in a study of HIV incidence among MSM in China by first recruiting persons to participate in a cross-sectional survey.20

Our pilot reinforced the importance of embedding any recruitment strategy within a broader community education effort that is not limited to HIV vaccine trial eligible black MSM or transwomen. Comprehensive community engagement and recruitment strategies should involve historically black institutions and other agencies with significant outreach to black MSM and transwomen populations.21 Only by increasing awareness of and commitment to participation in a wide range of studies can we find safe and effective alternatives to prevent HIV infection in heavily affected communities.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: A.C. was supported as a Research and Mentorship Program (RAMP) Scholar co-funded by NIAID HIV Vaccine Trials Network and the NIMH. J.F. and S.B. were supported under a NIAID Division of AIDS CTU award (U01A169470), and J.F. and W.M. received support through the NIMH-funded Summer HIV/AIDS Research Program (R25MH097591). The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the San Francisco Department of Public Health.

Footnotes

This work was presented at the AIDS Vaccine 2013, Barcelona, Spain, Oct 7-10, 2013 (Abstract P04.28)

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure Chemoprophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Men Who Have Sex with Men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 Infection with Early Antiretroviral Therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Estimated HIV incidence among adults and adolescents in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2012;17 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herbst JH, Jacobs ED, Finlayson TJ, et al. Estimating HIV Prevalence and Risk Behaviors of Transgender Persons in the United States: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9299-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Djomand G, Katzman J, Tommaso D, et al. Enrollment of racial/ethnic minorities in NIAID-funded networks of HIV vaccine trials in the United States, 1988 to 2002. Public Health Rep. 2005;120:543–548. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Umlauf BJ, Haralambieva IH, Ovsyannikova IG, et al. Associations between demographic variables and multiple measles-specific innate and cell-mediated immune responses after measles vaccination. Viral Immunol. 2012;25:29–36. doi: 10.1089/vim.2011.0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soneji S, Metlay J. Mortality Reductions for Older Adults Differ by Race/Ethnicity and Gender Since the Introduction of Adult and Pediatric Pneumococcal Vaccines. Public Health Rep. 2011;126:259–269. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newman PA, Duan N, Rudy ET, et al. Challenges for HIV vaccine dissemination and clinical trial recruitment: if we build it, will they come? AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2004;18:691–701. doi: 10.1089/apc.2004.18.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuchs JD, Buchbinder SP. Lessons Drawn From the AIDSVAX B/B vaccine efficacy Trial. In: Koff WC, Kahn P, Gust ID, editors. AIDS Vaccine Development: Challenges and Opportunities. Caister Academic Press; Norfolk: 2007. pp. 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newman PA, Duan N, Roberts KJ, et al. HIV Vaccine Trial participation among ethnic minority communities: Barriers, motivators, and implications for recruitment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:210–217. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000179454.93443.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moutsiakis DL, Chin PN. Why blacks do not take part in HIV vaccine trials. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:254–257. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen MA, Liang TS, Salvia TL, et al. Assessing the Attitudes, Knowledge, and Awareness of HIV Vaccine Research Among Adults in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40:617–217. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000174655.63653.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, et al. Attitudes and Beliefs of African Americans Toward Participation in Medical Research. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14:537–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuqua V, Chen YH, Packer T, et al. Using Social Networks to Reach Black MSM for HIV Testing and Linkage to Care. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:256–65. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9918-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 1997;44:174–99. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammer SM, Sobieszczyk ME, Janes H, et al. Efficacy Trial of a DNA/rAd5 HIV-1 Preventive Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2013 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCoy SI, Shiu K, Martz TE, et al. Improving the Efficiency of HIV Testing With Peer Recruitment, Financial Incentives, and the Involvement of Persons Living With HIV Infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63:56–63. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31828a7629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Overstreet NM, Earnshaw VA, Kalichman SC, et al. Internalized stigma and HIV status disclosure among HIV positive black men who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2013;25:466–71. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.720362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abramovitz M, Volz E, Strathdee S, et al. Using respondent-driven sampling in a hidden population at risk of HIV infection: who do HIV-positive recruiters recruit? Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:750–56. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181b0f311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan H, Yang H, Zhao J, et al. Long-chain peer referral of men who have sex with men: a novel approach to establish and maintain a cohort to measure HIV incidence, Nanjing, China. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59:177–84. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318239c947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelley RT, Hannans A, Kreps GL, et al. The Community Liaison Program: a health education pilot program to increase minority awareness of HIV and acceptance of HIV vaccine trials. Health Educ Res. 2012;27:746–54. doi: 10.1093/her/cys013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]