Abstract

Little is known about the intersections of immigration, masculinity, and sexual risk behaviours among recently arrived Latino men in the United States (USA). Nine immigrant Latino men from three urban housing communities in the South-eastern USA used photovoice to identify and explore their lived experiences. From the participants’ photographs and words, thirteen themes emerged within four domains. The immigration experience and sociocultural norms and expectations of masculinity were factors identified decreasing Latino men’s sense of power and increasing stress, which lead to sexual risk. Latino community strengths and general community strengths were factors that participants identified as promoting health and preventing risk. These themes influenced the development of a conceptual model to explain risk among immigrant Latino men. This model requires further exploration and may prove useful in intervention development.

Keywords: Latino, migrants, alcohol, HIV, sexual risk, USA

HIV and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) disproportionately affect vulnerable populations in the United States (USA), including immigrant Hispanic/Latino communities, who tend to be politically, socially, and economically disenfranchised (Institute of Medicine & Committee on Prevention and Control of Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 1997). Hispanics/Latinos have the second highest rate of AIDS diagnoses of all racial and ethnic groups (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2005). Although Hispanics/Latinos represented 14% of the continental US population in 2004 (US Census Bureau, 2005), they accounted for 20% of the total number of new AIDS cases reported, almost four times greater than that for non-Hispanic/Latino whites (CDC, 2005).

Rates of reportable STDs also are higher among Hispanics/Latinos than among non-Hispanic/Latino whites. In 2003, the rates of gonorrhoea, chlamydia, and syphilis each were two to four times higher among Hispanics/Latinos than among non-Hispanic/Latino whites (CDC, 2004). Between 2000 to 2003, primary and secondary syphilis rates increased by more than 20% among US Hispanics/Latinos each year, while declining among African Americans (CDC, 2004).

Alcohol use among immigrant Hispanics/Latinos has been assumed to be high; however, more systematic research is needed to accurately measure, document, and understand alcohol use among immigrant Hispanic/Latino groups. A recent review indicated that although Hispanic/Latino men may not be more likely to use alcohol, it may be that they drink heavily when they do drink (Worby & Organista, 2007).

Among many southern US states experiencing rapid growth of the Hispanic/Latino population, North Carolina (NC) has one of the fastest-growing Hispanic/Latino populations in the country (NC Institute of Medicine, 2003; US Census Bureau, 2005). Like many immigrants, these immigrants to the south-eastern USA come in search of employment opportunities; however, these Hispanic/Latino immigrants represent a new trend in immigration. They tend to come from southern Mexico and Central American countries including El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras; rather than locations that have in the past sent Hispanics/Latinos to the USA, including Northern Mexico and the Caribbean (NC Institute of Medicine, 2003).

Some factors associated with immigration may increase vulnerability to HIV infection and alcohol consumption. Increased poverty rates, harsh labour conditions, and racial discrimination may challenge self-image and traditional Hispanic/Latino values (Amaro, Vega, & Valencia, 2001; Bajos, 1997; Diaz, Ayala, Bein, Henne, & Marin, 2001; NC Institute of Medicine, 2003; Organista, Carrillo, & Ayala, 2004; Worby & Organista, 2007). Immigrants must cope with conflicting cultural and social norms and expectations while attempting to adjust to life in a new country (Brettell, 2000; Portes, 1997). Norms and expectations, including those related to sexual behaviour and gender roles (whether positive or negative, healthy or unhealthy) may be challenged (Brettell, 2000; Organista et al., 2000; Pulerwitz, Amaro, De Jong, Gortmaker, & Rudd, 2002; Streng et al., 2004), and for some, the subsequent loneliness, depression, and stress may result in higher rates of risk behaviour and increased rates of sexual and alcohol risk behaviours (Aranda-Naranjo & Gaskins, 1998; Organista et al., 2000; Williams, 2003; Worby & Organista, 2007; Zambrana, Cornelius, Boykin, & Lopez, 2004).

Although sexual orientation, nationality, and socioeconomic status may contribute to differential infection rates among subgroups of Hispanics/Latinos, it is clear that immigrants currently arriving to the south-eastern USA are at increased risk based on environmental factors including limited knowledge of and access to prevention, care, and treatment services; limited bilingual services; stigma and discrimination; and segregation and social exclusion; and behavioural risk factors including increased use of commercial sex workers and inconsistent condom use (Rhodes, Hergenrather, Wilkin, Alegria-Ortega, & Montaño, 2006).

Most of what is currently known about the epidemic is based on experiences in early epicentres of the US epidemic with a history of providing prevention, care, and treatment services (Rhodes, Yee, & Hergenrather, 2006). These epicentres tend not to reflect the unique characteristics of the resource-poor South (Aral, O’Leary, & Baker, 2006; Rhodes, Hergenrather, Wilkin, & Jolly, 2008). Moreover, much of what is known about HIV among Hispanics/Latinos in the USA is based on communities that have both a longer history of Latino immigration and a further developed infrastructure, and thus access, to address their needs (Rhodes, Hergenrather, Wilkin, Alegria-Ortega, & Montaño, 2006).

Our objectives in this study were to: (1) identify and explore the potential determinants of sexual risk among recently arrived, immigrant Latino men1 living in a region of the USA that is experiencing both the fastest-growing Latino population and disproportionate HIV and STD infection rates and (2) use these findings to develop a conceptual model of sexual risk in partnership with the participants themselves. A community-university partnership used community-based participatory research and the photovoice method to elicit qualitative themes and inform a conceptual model.

Methods

Study Design

This study was conceived and conducted by a community-university partnership that includes lay community members and representatives from local community-based organizations (CBOs), such as AIDS service organizations (ASOs) and religious organizations; a public health department; a community college, a historically black university, and a medical school. This partnership serves as a catalyst for identifying priorities and approaches to meet local HIV/AIDS prevention and care needs (Bowden, Rhodes, Wilkin, & Jolly, 2006; Rhodes, 2004, 2006; Rhodes & Hergenrather, 2007; Rhodes, Duncan, et al., 2007; Rhodes, Eng et al., 2007; Rhodes et al., 2006; Rhodes, Hergenrather, Yee, & Ramsey, 2008).

The partnership has prioritized community-based participatory research to promote a co-learning, empowering, and collaborative process that emphasizes: reciprocal transfer of expertise; sharing of decision-making power that allows negotiation and tradeoffs with traditional power holders (e.g., university researchers) and community members and CBO and agency representatives; and mutual ownership of the processes and products of research (Israel et al., 1998; Viswanathan et al., 2004). Community-based participatory research recognizes that an outsider can work best with community partners, who themselves are experts. This style of research does not require specific data collection and analysis methods; however, photovoice has gained momentum as a method to ensure research is community driven (Rhodes & Benfield, 2006).

Procedure

We applied photovoice as a method of inquiry (Wang & Burris, 1997). A qualitative and exploratory research methodology founded on the principles of constructivism (Patton, 1990), critical theory (Morrow & Brown, 1994), health promotion (Green, Krueter, & Krueter, 1999), empowerment education (Freire, 1970, 1973), and documentary photography (Sontag, 1977; Wang & Burris, 1994), photovoice enables participants to record and critically reflect on their own strengths and concerns and those of their community through photographic images. It allows participants to define their concerns and priorities. Rather than the researcher defining the direction, photovoice allows rich detail to emerge through a process that ensures that the lived experiences of participants are identified, prioritized, and interpreted through ongoing critical dialogue (Wang & Burris, 1997).

Setting and participants

This study took place between September and December 2004 in Forsyth County, NC, which has >300,000 residents. Predominantly of Mexican origin, the Latino community in this county grew by >900% in the past decade (US Census Bureau, 2005). This county ranks third in the state for its HIV infection rate, nearly double the NC rate. Participants were recruited from three urban housing communities in Winston-Salem. These housing communities were selected based on their high Latino census (each ≥95% Latino).

Participant recruitment and retention

A convenience sample was used. Three men from each of the three largest housing communities were recruited by staff from a CBO partner with a strong Latino outreach program. All participants reviewed and signed a Spanish-language consent form and attended all photo-discussions and data analysis and interpretation sessions, all of which were held in Spanish. A one-hour introductory meeting was held for participants to discuss the photovoice process, ethics and safety in photography, and camera operation. Participants received a $10 gift card for each session attended and a disposable camera for each photo-assignment, one copy of each photograph taken, and film remaining after taking the study-related photos could be used to take pictures of anything they wanted.

Measures

A short Spanish-language questionnaire collected demographics about participants, including age, self-identified race/ethnicity, country of origin, formal education, number of months since arrival in US, employment status, partnership status in the USA (i.e., whether accompanied or unaccompanied), and sexual behaviour.

Acculturation was measured with a 12-item scale that assessed how often participants speak, listen to, and use English and Spanish (Marin, Sabogal, Marin, Otero-Sabogal, & Perez-Stable, 1987). Scores ranged from 1.00-3.25 on a scale of 1 to 5, with lower values representing less acculturation. Reliability of the scores in this sample was excellent (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93) and similar to other samples of immigrant Latino men in NC (Rhodes et al., 2006).

Participants used a consensus-building process to determine the topics for each photo-assignment. The photo-assignments for each of the four photo-discussions were decided upon by the participants as a group, not by the researchers. In sequential order, the photo-assignments were: (1) Community strengths; (2) Education; (3) Services; and (4) HIV/AIDS prevention. A summary photo-discussion followed.

Photo-discussions and supplemental data analysis and interpretation sessions were scheduled on Saturday mornings, were held in a convenient location, lasted approximately 1.5-2.0 hours, and were audio-recorded.

Two male facilitators led the photo-discussions and supplemental sessions. One facilitated the photo-discussions, and the other operated the audio-recorder, took notes, and collected the shared photographs. The primary facilitator was a native Spanish speaker; the second facilitator was Spanish proficient.

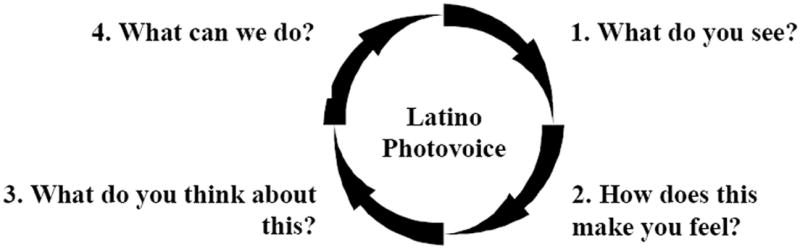

Photo-discussions began with a review and discussion of themes that emerged from the analysis of previous sessions. During the photo-discussions, each participant shared up to three photographs with the group through a facilitator-guided discussion based on the process illustrated in Figure 1. This process used the photographs as triggers for discussion. After the photo-discussion, the participants determined a topic for their next photo-assignment.

Figure 1. Guide to the Photovoice Discussion Process.

Data preparation, analysis, and interpretation

After each photo-discussion, the facilitators documented initial general impressions about the process and content. Next, they listened to the audio-recorded discussion and took general notes. Then, the discussion was transcribed in full detail by a professional transcriptionist in both Spanish and English.

After photo-discussions transcripts were verified in Spanish and English, members of the analysis team (an ad hoc committee of the partnership comprised of representatives from the lay Latino community [n=2], the health department [n=1], two ASOs [n=3], and a university [n=1]) completed a multistage inductive interpretative process that included participant involvement in data analysis and interpretation. Grounded theory was used, focusing on understanding a wide array of experiences and building understanding on real-world patterns inductively to generate theory that is based in empirical data (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). The analysis team used open coding which included exploring, examining, and organizing the transcript data into broad conceptual categories and refined codes within and across the transcripts using constant comparisons. Codes were reviewed to generate initial themes (Silverman, 2001).

Preliminary codes and themes were presented to all participants. This process was iterative with the analysis team providing technical analytic draft theme development through a process that included ongoing identification and evaluation of proposed codes, themes, and categories, and constant comparison of similarities and differences across transcript data, and the participants revising, further developing, approving, and interpreting these themes. These meetings were conducted until the participants felt that the findings depicted what they themselves experienced and wanted others to understand about their lived experiences (Bowden et al., 2006; Hergenrather, Rhodes, & Clark, 2006; Morse, 1994; Rhodes et al., 2007).

Subsequently, during three supplementary meetings, the themes were compiled into a conceptual model of sexual risk. The first meeting explored how participants themselves fit the findings together. They drafted a preliminary conceptual model. The second and third meetings offered the opportunity for further clarification, refinement, and interpretation of the model. The participants themselves developed and interpreted this model.

Results

Nine Latino men participated, three from each of three housing communities. Mean age was 23.8 (SD=3.6), ranging from 18-29 years. All participants self-identified as Latino; four reported being from rural communities in El Salvador, four from Mexico, and one from Guatemala. All were recently arrived, having lived in the USA 12.6 (SD=3.4) months, ranging from 6-18 months. All participants reported completing equivalent to eighth grade or below and having had sexual intercourse with women as opposed to men in the past two years. Seven of the nine reported being undocumented. Acculturation was low with a mean score of 1.8 (SD=0.7). Eight of the nine participants reported working in construction and one reported working in the food service industry. Participants were not day labourers.

Thirteen primary themes emerged from the analysis of photo-discussions. These themes were organized into four domains: (1) the immigration experience and (2) sociocultural norms and expectations of masculinity as factors that the participants identified as decreasing Latino men’s sense of power and increasing their stress, which in turn lead to sexual risk; and (3) Latino community strengths and (4) general community strengths as factors that the participants identified as promoting sexual health and preventing risk.

Immigration as a Factor Decreasing Power and Increasing Stress

Immigration was identified as contributing to decreased power and increased stress that can lead to sexual risk and high-risk alcohol use among Latino men through six themes: limiting visits home because of restrictive US borders that are difficult to cross; forgoing friends, family, and material possessions to come to the USA; facing discrimination after arriving in the USA; living in substandard housing; working in harsh conditions after becoming employed in the USA; and having limited access to health care.

Tight US borders

Participants reported that the US border seems more difficult to cross and thus reported being less likely to travel back to their countries of origin. As one participant from Mexico noted,

“I think Latinos were more likely to travel back and forth [across the border]. Now, we don’t though. It is not easy to do… We can’t go back [to communities of origin] and visit.”

Responding another participant added, “We can’t go to our countries. We can’t get reprieve and that makes life harder and hurts us. Some [men] turn to alcohol.”

Coming to the USA, which for some participants meant crossing multiple borders (e.g., the Guatemalan participant reported the challenges of crossing both the Mexico and US borders), was identified as difficult. They emphasized the inability to return home as contributing to decreased power and increased stress by participants, which increased the likelihood they would engage in unhealthy behaviours such as sexual risk and high-risk drinking. Another participant continued, “Many of us do things that are not good, engaging in behaviours that jeopardize our health because we can’t go home.”

Giving up family, friends, and possessions

Participants also described the sacrifices they made to come to the USA and emphasized the difficulties associated with leaving close family and friends, selling all of their material possessions, and not having anything in their country if they were to leave the USA permanently. One man said,

“I have nothing in Mexico. I gave it all up to get the money to come here. It was a sacrifice and it is painful in my heart.”

Faced with discrimination

After arriving in the USA, participants reported feeling that they were faced with discrimination from both the general community and within the local Latino community. These experiences decreased their sense of power and increased their stress. A participant shared,

“Look in the paper. We hear on the radio. No one wants us here, yet they want us to get the work done for little pay. Now that is racist. Many people in the USA look down on us as Latinos and then appreciate, should I say, the [fruits] of our labour. That is not right.”

Participants also noted intra-community discrimination based on country of origin, Spanish- and English-language proficiency, and length of time since arriving in the USA. Reference was made about Mexicans perceiving themselves as ‘superior’ to Central Americans, and participants reported that Latinos who speak indigenous languages (as opposed to Spanish) or have less English-language proficiency are often regarded as inferior. A participant noted that some Latinos may refer to other Latinos as “indios” or “indians” if they appear to look indigenous. This is a derogatory use of the word that implies one is uncivilized.

Substandard housing

Participants reported feeling like they were being taken advantage of by their landlords who did little upkeep on the houses, apartments, and trailers that many immigrants rent because they may feel like they have no legal recourse. As one participant commented, “Man, we aren’t from here and some of us don’t have papers. We are stuck and can’t do anything about it.”

Another participant continued, “One feels powerless and frustrated. It makes you think you are less than you are, less than human, like an animal. You just do not think about it and some use alcohol or go to the women because all these stresses build up. You have to handle it in what ever way.”

Harsh working environments

Participants also reported that although immigrating to the USA meant an income, working conditions were challenging. They discussed long hours, unsafe working conditions, and little recourse in effecting change. A participant summarized a discussion by saying,

“I will work on roofs that other men won’t, maybe they wouldn’t dare. I am talking steep and high with no safety equipment, but they, my bosses, don’t care. It is the way of life for the Latino man, especially in the US.”

Limited access to preventive or health services

Participants reported feeling that they have little access to services. Besides language barriers, participants reported other barriers including: limited public health services for men; limited hours of service provision; difficulty to leave work for appointments; and the need for more male providers and male interpreters.

Participants also indicated that HIV and STD information and resources are difficult to find and access in the USA. Comparing his experience in El Salvador to his experience in the USA, a participant explained,

“In my country, you see – wherever you go – information, advertising, and publicity about preventing AIDS. There are warnings about AIDS and billboards about using condoms, but here [in the USA] it is different. To me, it seems harder for Latinos to get what they may need, including information about AIDS and condoms.”

Masculinity as a Factor Decreasing Power and Increasing Stress

Masculinity comprised two themes: participants feeling that they have had to take on untraditional roles and the difficulty in their meeting sociocultural expectations of what it means to be a man.

Taking on untraditional roles

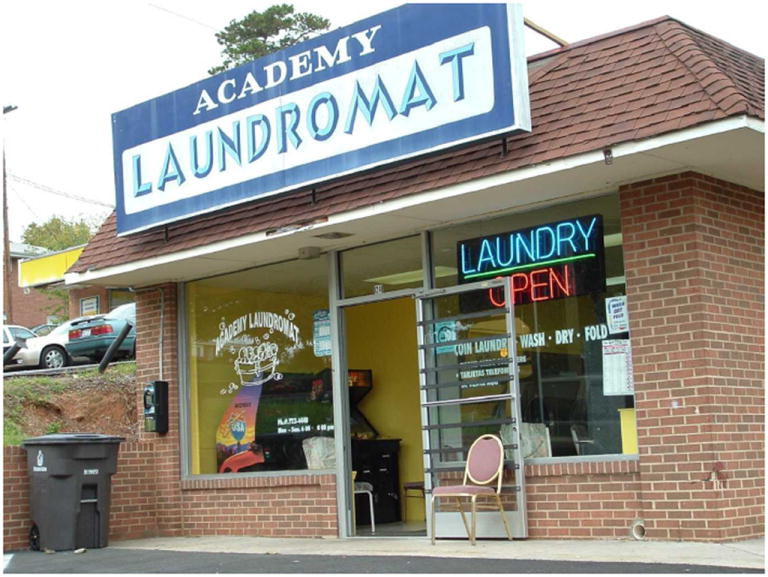

Participants acknowledged the added roles they had to assume in order to adjust to life in the USA. Referring to Figure 2, a participant explained,

“This really shows you something. Men just like us, come to the US and have to take on these types of roles. Besides this, we have to cook and clean and make do without the supports that we are used to. There are no women to help us. This is a Laundromat that some Latino men have to go to because there is no one to help us.”

Figure 2. Taking on Untraditional Roles: “Besides this, we have to cook and clean and make do without the support that we are used to”.

Not meeting sociocultural expectations of manhood

Participants also reported the stress associated with engaging in behaviours (e.g., doing laundry, cooking) that, within their culture and sending communities, are typically done by females. Although they accepted this as a fact of immigration, participants noted the effect this had on their self-image. As one man said, “We do what we have to do to survive but it is hard… [when] the people where we are from would tell us it is not manly.”

Another participant noted, “Some men, some Latino men just like me, are going to do what it takes to show others that they are men. You know, how men are supposed to be: strong, in charge, macho.”

Participants were not judging cooking and cleaning as less valuable activities; rather, they recognized that as immigrants their roles had changed in ways that challenged cultural expectations and social norms in their countries of origin. They recognized a division of labour that, although socially constructed, still impacted their perceptions of what they should be doing in their roles as men. In fact, the Guatemalan participant noted that he had to manage his money. In the area in Guatemala that he came from, money was handled by the woman of the household (see Carter, 2004); so he acknowledged that he now had to develop the skills and remedy the conflict he felt about handling household finances.

Community Strengths as Factors Promoting Health and Preventing Risk

Participants identified three Latino (family and friendship networks, the soccer leagues and teams, and the burgeoning Latino economic community) and two general community strengths (jobs and Latino-serving and promoting organizations), all of which were identified as promoting wellbeing and health and preventing risk.

Friendship and family networks

Participants reported a reliance on family and friendship networks to assist recent arrivals in finding a place to live, getting a job, and settling in (e.g., where to shop and do laundry and how to buy a car). Unlike those individuals identified in the immigration domain, these family and friends tended to be more distant and not one’s mother or father. As a participant reported, “We come to locations where our family is, you know, maybe an uncle or cousin sent word.”

Soccer leagues and teams

The participants reported the important role that the Latino soccer leagues play in their lives. Teams are structured around family networks and communities of origin. Besides serving as an activity for Latino immigrants, soccer leagues and teams also were identified as broadening their social support networks.

The burgeoning Latino economic community

Participants also noted that the growing Latino community in NC offered opportunities to “feel comfortable.” Tiendas (Latino grocers) offer participants a place to shop and buy traditional foods and products. Two potentially negative aspects were identified with tiendas. Participants suggested that inflated prices took advantage of immigrants who did not speak English. Those who did not speak English had fewer other options and tended to rely on tiendas more frequently because of the tiendas’ Spanish-speaking staff. Second, participants also wondered whether tiendas sold products that had been imported into the USA illegally. As a participant reported,

“You can buy medications, which require a prescription in the USA, without a prescription… We don’t know what we are getting. Some people are ok with that but I am not. But what choice do I have? I can’t see a doctor in the US so I have to go the tienda and get what I need when I am sick or hurt.”

Latino “discos” were identified as places Latinos can congregate and hear music they are familiar with. Spanish radio and print media also were identified as further resources for recently arrived Latinos to learn about settling into life in the USA.

Employment opportunities

Other community strengths included the existence of local jobs. A participant asserted, “I am here to work and I wouldn’t be here if there weren’t jobs so that is good.”

Latino serving and promoting organizations

Participants also acknowledged the importance of Latino-serving and promoting organizations that work within their communities. These organizations were predominantly led by Latino leadership; however, a few community-based organizations have begun to meet the needs of the growing Latino community and have been increasing their capacity to offer bilingual and culturally relevant services.

The Conceptual Model

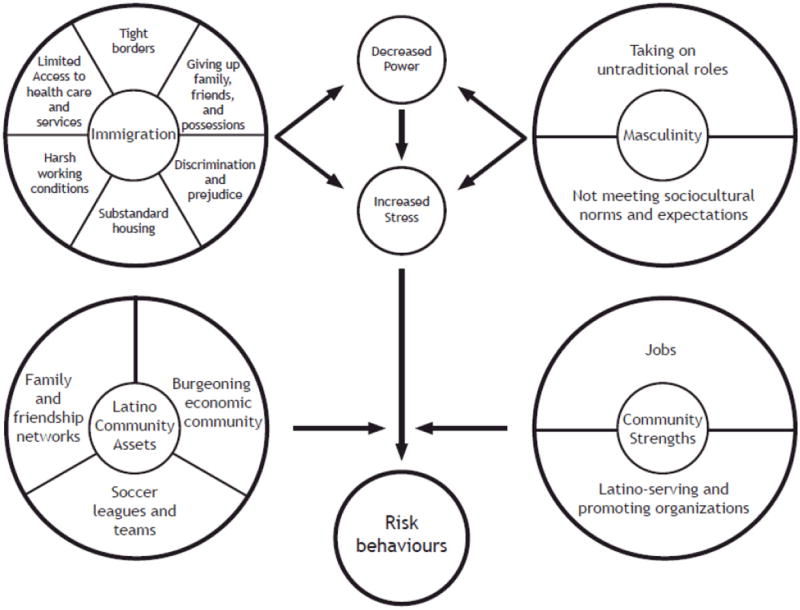

In partnership with the analysis team, the participants developed of a conceptual model (Figure 3) to illustrate the relationships among the themes and their potential relationships to sexual behaviour.

Figure 3. Conceptual Model of Immigrant Men’s Risk as Developed by the Community-Based Participatory Research Partnership.

The model suggests that themes identified – those related to immigrating to the USA, taking on untraditional roles, and not being able to meet sociocultural norms and expectations of what it means to be a man – all contribute to both an actual and perceived decreased power and increased stress. As one man said, “All of these changes and a change in our status make us feel small, and without power.” Another participant noted that he was a school teacher in El Salvador and “here I am seen as unskilled labour.”

Another participant concluded,

“Look at this model that we created. You can see some of the major influences on our behaviour as men and my behaviour, or the sex [behaviours] and drinking of our friends, and I say many Latino men living in the USA, just like me. Living in the USA is difficult; coming to the USA is difficult. We have to take new things on. Doing new things costs us. Difficulties are compounded. Things can be good but coming here is difficult too. When things are difficult, I may take risks. Who thinks of a condom when one is trying to escape or prove oneself? Who thinks of a condom when the pressure of life here is great?”

Participants suggested that Latino community assets (e.g., family and friendship networks; the soccer leagues and teams, and the burgeoning Latino economic community) and general community strengths (e.g., jobs and Latino-serving and promoting organizations) may serve to moderate the outcomes resulting from decreased power and increased stress: sexual and alcohol risk behaviours. As a participant warned, “Without some of these positive aspects of living here, things would even be worse for the Latino man.”

Another participant commented, “If you can find a place with support, you won’t be so alone. You might be able to make it work for you.”

An important component of the model includes the relationship between sexual and alcohol behaviours hypothesized by the participants. Alcohol use was conceived as contributing to sexual risk behaviours such as not using a condom or having multiple partners. As a participant said, “You cannot take the pressure, you drink, and then you want sex and have no thoughts about protection.”

Similarly, sexual risk was identified as contributing to increased alcohol use; for example, participants felt that a man may engage in sexual risky behaviour (defined by the participants as sexual intercourse with multiple partners, without a condom, and sex workers), and then feel worried, not know where to go for STD counselling and testing, and may engage in high-risk drinking because of his increased negative mood state.

Discussion

This study sought to obtain rich qualitative insight into the lived experiences of recently arrived, less acculturated, monolingual (Spanish-speaking) immigrant Latino men in a region of the USA that is experiencing both the fastest growing immigrant Latino population in the country and disproportionate HIV and STD infection rates. Using photovoice, a method often aligned with community-based participatory research, this study blended: the lived experiences of immigrant Latino men; the expertise of frontline community members who work to improve the health and wellbeing of Latinos; and the scientific perspectives of researchers to develop an authentic understanding and a meaningful appreciation of immigrant Latino men’s lives. Participants identified, described, discussed, and organized the intersections of their own immigration experience; their perceptions of sociocultural notions of what it means to be a man; and the moderating effects of community strengths. This process also included the development, refinement, and interpretation of a conceptual model that deserves exploration and empirical testing, and may serve as a guide for intervention.

Many of the participants reported a sense of decreased power and increased stress related to restrictive US borders that make crossing difficult and visits to their countries of origin infrequent. Immigrants often come from communities of political unrest and are faced with a difficult and dangerous border crossing experience that research confirms may yield psychological disturbances and stress disorders (Cervantes, Salgado de Snyder, & Padilla, 1989; Eisenman, Gelberg, Liu, & Shapiro, 2003). The experience of giving up family, friends, and material possessions (although to improve the quality of life of their families “back home”) also was identified as promoting a sense of decreased power and increased stress for these participants and thus resulted in risk behaviours. These stressors and potential symptoms of depression (e.g., depressed mood) may increase men’s use of unhealthy coping strategies, including increased sexual activity and sexual risk. This negative affect has been identified as associated with increased comfort food consumption and substance use (Jackson & Knight, 2006).

Participants noted discrimination against immigrant Latinos was common. They discussed how it affected their feelings about themselves and its potential effects. Discrimination and its effect on health and wellbeing of minority populations has been commonly identified as affecting health and wellbeing (Institute of Medicine, 2003). However, few programmes and have been developed to transform a community through some type of socio-political or cultural intervention (Guerin, 2005; Institute of Medicine, 2000).

Participants also noted that being undocumented and/or not speaking English forced them to withstand substandard housing at increased cost because they felt they had no rights and thus no legal recourse. Similarly, harsh working conditions also were identified by the participants as having negative effects through sexual and alcohol risk.

The final theme that was included within the immigration domain was limited access to health care and services. Latino immigration has shifted from regions of the USA with a longer history of Latino immigration (e.g., Western and Midwestern USA) to the South-eastern USA, a region in which health departments, for example, have difficulty providing Spanish-language services, staffing after-hours clinics when Latino men are available for services, providing offsite clinical services (e.g., workplaces), and marketing available services within Latino communities, especially for Latino men (Rhodes et al., 2007). Additional resources may need to follow this changing immigration demographic.

Masculinity has been suggested to be associated with risk, but empirical evidence has been limited (Fiorentino, Berger, & Ramirez, 2007; Mahalik, Burns, & Syzdek, 2007; Rhodes et al., 2006). Whitehead (1997), however, argues that men are socialized to believe that there are three aspects of their gender selves: economic, socio-political, and sexual. Men’s inability to be successful economically and socially increases the likelihood that they will try to exhibit masculinity through increased sexual prowess and often increased sexual risk. Although Whitehead’s research was conducted with Jamaican and African American men, the efforts for men to utilize sexuality to demonstrate that they too are ’strong men’ may be relevant for immigrant Latino men too. These men are struggling to reconcile their difficulties fulfilling traditionally masculine roles (e.g., economic and socio-political roles), and may use increased sexual behaviour and sexual risk to try and salvage their gender selves. Besides focusing on the positive aspects of manhood and reframing the negative aspects to reduce risk, interventions that help immigrant men effectively manage the incongruence between the practical realities of immigrating to the USA, such as taking on roles that may be less common for men and do not meet sociocultural norms and expectations and the culturally defined roles that are traditionally ascribed to men in their cultures, may be effective at reducing risk among immigrant Latino men. Clearly, further research is needed to explore and characterize the important and changeable perspectives around the intersections of immigration, masculinity, and risk.

Community assets and strengths were identified that can be strengthen and/or utilized for promoting health and preventing disease, particularly approaches that utilize existing family and friendship networks, other social networks (e.g., soccer leagues and teams), and workplaces.

Study Limitations

The findings of this study are limited to the men who participated in this study. As such, they are associated with the participants’ own experiences and may not be generalizable. However, the purpose of this exploratory study was to discover relevant factors and work with Latino men themselves to create a relevant conceptual model. Furthermore, the model includes only variables that the participants identified as key. Perhaps a refined model, with other variables that have been identified as associated with risk (e.g., loneliness, low educational attainment, limited English-language proficiency [Bronfman & Moreno, 1996]), would produce a more comprehensive and predictive model of immigrant Latino men’s risk behaviour.

Moreover, the degree to which each domain and theme that was identified and delineated in the model differed by participant. However, these men worked iteratively through ongoing discussion and debate to develop a model that they decided “fit” their collective experiences.

Conclusions

Photovoice provided an emic perspective from immigrant Latino men regarding immigration, masculinity, and risk. It offered immigrant Latino men an opportunity to author individual and collective stories that represent their own lived experiences, and formulate a conceptual model. We were able to explore how the participants themselves conceptualized the “logic” of their risk, gaining a balanced model that highlighted potential leverage points. In short, the participants explained sexual risk and alcohol use as insiders, not as outside researchers or practitioners looking in. This model offers a depiction of risk and operationalizes some of the factors that may contribute to Latino men’s vulnerability.

Given the immediate needs brought by the HIV and STD epidemics, research and practice that build knowledge through combining community member insights based on their own lived experiences, the expertise of frontline personnel, and the experiences and training of researchers is warranted. Photovoice is more than a basic research method; it facilitates participant empowerment by creating a space for participation and control over the process and builds the capacity of participants to mobilize to explore, describe, and analyze challenges and assets and problem solve. As a male participant commented, “I am an expert of my own life. You [practitioners and researchers] may know a bit, but I can tell you what is going on with me better than you may think.”

As the HIV and STD epidemics have evolved over the years, a need exists to creatively explore, understand, and intervene upon factors associated with exposure and transmission, especially among vulnerable communities. Nowhere is this more urgent than in the region of the US that is experiencing the most rapid growth rate of the Latino community and bearing a disproportionate burden of AIDS, HIV and STDs.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by Forsyth County United Way and Wake Forest University School of Medicine Venture Funds (awarded to SDR). Human subject protection oversight was provided by the Wake Forest University Health Sciences Institutional Review Board. LJY was supported by 1KL RR024154-01. DMG was supported by 1-U48-DP-000055 and 5-R25-GM058641. We also thank Karen Klein (Research Support Core, WFUHS), for her invaluable editorial contributions to this manuscript.

Footnotes

We note that although the classification Hispanic/Latino comprises a broad spectrum of individuals, countries of origin, and cultural meanings and perspectives, like many recently arrived Spanish-speaking immigrants to the South-eastern USA, the participants in this study chose to identify themselves by the term Latino.

References

- Amaro H, Vega RR, Valencia D. Gender, context, and HIV prevention among Latinos. In: Aguirre-Molina M, Molina CW, Zambrana RE, editors. Health Issues in the Latino Community. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2001. pp. 301–324. [Google Scholar]

- Aral SO, O’Leary A, Baker C. Sexually transmitted infections and HIV in the Southern United States: An overview. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2006;33(7 Suppl):S1–5. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000223249.04456.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranda-Naranjo B, Gaskins S. HIV/AIDS in migrant and seasonal farm workers. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 1998;9(5):80–83. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(98)80035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajos N. Social factors and the process of risk construction in HIV sexual transmission. AIDS Care. 1997;9(2):227–237. doi: 10.1080/09540129750125244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden WP, Rhodes SD, Wilkin A, Jolly C. Sociocultural determinants of HIV/AIDS risk and service utilization among immigrant Latinos in North Carolina. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2006;28(4):546–562. [Google Scholar]

- Brettell CB. Theorizing immigration in anthropology: The social construction of networks, identities, communities, and global landscapes. In: Brettell CB, Hollifield JF, editors. Migration theory: Talking across disciplines. New York, NY: Routledge; 2000. pp. 97–135. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfman N, Moreno L. Perspectives on HIV/AIDS prevention among immigrants on the US-Mexico border. In: Mishra S, Conner R, Magaña R, editors. Aids crossing borders: The spread of HIV among migrant Latinos. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1996. pp. 49–76. [Google Scholar]

- Carter MW. Gender and community context: An analysis of husbands’ household authority in rural Guatemala. Sociological Forum. 2004;19(4):633–652. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2003. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS surveillance report, 2003 (No 15) Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes RC, Salgado de Snyder VN, Padilla AM. Posttraumatic stress in immigrants from Central America and Mexico. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1989;40(6):615–619. doi: 10.1176/ps.40.6.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Henne J, Marin BV. The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: Findings from 3 US cities. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(6):927–932. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenman DP, Gelberg L, Liu H, Shapiro MF. Mental health and health-related quality of life among adult Latino primary care patients living in the united states with previous exposure to political violence. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290(5):627–634. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentino DD, Berger DE, Ramirez JR. Drinking and driving among high-risk young Mexican-American men. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2007;39(1):16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Herder and Herder; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Education for critical consciousness. New York, NY: Seabury Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Green LW, Krueter M, Krueter MW. Health promotion planning: An educational and environmental approach. 3. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Guerin B. Combating everyday racial discrimination without assuming racists or racism: New intervention ideas from a contextual analysis. Behavior and Social Issues. 2005;14(1):46–70. [Google Scholar]

- Hergenrather KC, Rhodes SD, Clark G. Windows to work: Exploring employment-seeking behaviors of persons with HIV/AIDS through photovoice. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(3):243–258. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Promoting health: Intervention strategies from social and behavioral research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine & Committee on Prevention and Control of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. The hidden epidemic: Confronting sexually transmitted diseases. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Knight KM. Race and self-regulatory behaviors: The role of the stress response and hpa axis in physical and mental health disparities. In: Carstensen LL, Schaie KW, editors. Social structure, aging and self-regulation in the elderly. New York, NY: Springer; 2006. pp. 189–207. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Burns SM, Syzdek M. Masculinity and perceived normative health behaviors as predictors of men’s health behaviors. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64(11):2201–2209. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9(2):183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow RA, Brown DD. Critical theory and methodology. Vol. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. Designing funded qualitative research. In: Denzen N, Lincoln Y, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 220–235. [Google Scholar]

- North Carolina Institute of Medicine. NC Latino health 2003. Durham, NC: North Carolina Institute of Medicine; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Organista KC, Carrillo H, Ayala G. HIV prevention with Mexican migrants: Review, critique, and recommendations. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;37(Supplement 4):S227–S239. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000141250.08475.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organista KC, Organista PB, Bola JR, Garcia de Alba JE, Castillo Moran MA, Soloff PR. Predictors of condom use in Mexican migrant laborers: Exploring AIDS-related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of female Mexican migrant workers. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(2):245–265. doi: 10.1023/a:1005191302428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Second edition. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A. Immigration theory for a century: Some problems and opportunities. International Immigration Review. 1997;31(4):799–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Amaro H, De Jong W, Gortmaker SL, Rudd R. Relationship power, condom use and HIV risk among women in the USA. AIDS Care. 2002;14(6):789–800. doi: 10.1080/0954012021000031868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD. Hookups or health promotion? An exploratory study of a chat room-based HIV prevention intervention for men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16(4):315–327. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.4.315.40399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD. Visions and voices- HIV in the 21st century: Indigent persons living with HIV/AIDS in the southern USA use photovoice to communicate meaning. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2006;60(10):886. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Benfield D. Community-based participatory research: An introduction for the clinician researcher. In: Blessing JD, editor. Physician assistant’s guide to research and medical literature. 2. Philadelphia, PA: F. A. Davis; 2006. pp. 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Duncan J, Hergenrather KC, Yee LJ, Knipper E, Wilkin AM, et al. Characteristics of a sample of men who have sex with men, recruited from gay bars and internet chat rooms, who report methamphetamine use. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2007;21(8):575–583. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Eng E, Hergenrather KC, Remnitz IM, Arceo R, Montaño J, et al. Exploring Latino men’s HIV risk using community-based participatory research. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2007;31(2):146–158. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC. Recently arrived immigrant Latino men identify community approaches to promote HIV prevention in the Southern USA. American Journal of Public Health. 2007 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.107474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Montaño J, Remnitz I, Arceo R, Bloom FR, et al. Using community-based participatory research to develop HoMBReS: An intervention to reduce HIV and STD infection within a Latino soccer league. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(5):375–389. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Wilkin A, Jolly C. Visions and voices: Indigent persons living with HIV in the southern US. Use photovoice to create knowledge, develop partnerships, and take action. Health Promotion Practice. 2008;9(2):159–169. doi: 10.1177/1524839906293829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Yee LJ, Ramsey B. Comparing MSM who participated in an HIV prevention chat room-based outreach intervention and those who do not: How. 2008 doi: 10.1093/her/cym015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Wilkin A, Alegría-Ortega J, Montaño J. Preventing HIV infection among young immigrant Latino men: Results from focus groups using community-based participatory research. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2006;98(4):564–573. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Yee LJ, Hergenrather KC. A community-based rapid assessment of HIV behavioural risk disparities within a large sample of gay men in southeastern USA: A comparison of African American, Latino and white men. AIDS Care. 2006;18(8):1018–1024. doi: 10.1080/09540120600568731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman D. Interpreting qualitative data: Methods for analysing talk, text and interaction. London: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag S. On photography. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Streng JM, Rhodes SD, Ayala GX, Eng E, Arceo R, Phipps S. Realidad Latina: Latino adolescents, their school, and a university use photovoice to examine and address the influence of immigration. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2004;18(4):403–415. doi: 10.1080/13561820400011701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. 2005 American community survey data profile highlights: North Carolina fact sheet. Vol. 2005. Washington, DC: United States Department of Commerce; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M, Eng E, Ammerman A, Gartlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D, Rhodes SD, et al. Community-based participatory research: Assessing the evidence (Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 99) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Burris MA. Empowerment through photo novella: Portraits of participation. Health Education Quarterly. 1994;21(2):171–186. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education and Behavior. 1997;24(3):369–387. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead T. Urban low-income African American men, HIV/AIDS, and gender identity. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1997;11(4):411–447. doi: 10.1525/maq.1997.11.4.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR. The health of men: Structured inequalities and opportunities. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(5):724–731. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worby PA, Organista KC. Alcohol use and problem drinking among male Mexican and Central American Im/migrant laborers: A review of the literature. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2007;29(4):413–455. [Google Scholar]

- Zambrana RE, Cornelius LJ, Boykin SS, Lopez DS. Latinas and HIV/AIDS risk factors: Implications for harm reduction strategies. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(7):1152–1158. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]