Abstract

For many years IL-33 has been widely studied in the context of T helper type 2 (TH2)-driven inflammatory disorders. Interestingly, IL-33 has now emerged as a cytokine with a plethora of pleiotropic properties. Depending on the immune cells targeted by IL-33, it is reported to not only promote TH2 immunity, but also to induce T helper type 1 (TH1) immunity. Furthermore, recent studies have revealed that IL-33 can activate CD8+ T cells. These new studies provide evidence for its beneficial role in antiviral and antitumor immunity. Here we review the evidence of IL-33 to drive protective T cell immunity plus its potential use as an adjuvant in vaccination and tumor therapy.

Introduction

Interleukin 33 (IL-33) was first described in 1999 by Onda H and colleagues who identified it as DVS27—a 30-kDa protein highly expressed in canine vasospastic cerebral cells (1). Four years later the corresponding gene was found to be highly expressed in the nucleus of high endothelial cells and this gene was termed “nuclear factor of high endothelial venules (NF-HEV)” (2). In 2005, through computational sequence comparison, Schmitz J and colleagues revealed that the C-terminal end of IL-33 contained a β-sheet trefoil-fold structure characteristic of the Interleukin 1 (IL-1) family (3). IL-33 thus became the 11th identified IL-1 family member. Subsequently, IL-33 was recognized as the functional ligand for the orphan IL-1 receptor ST2 (also called IL-1R-like-1) (3). ST2 is selectively expressed on the cell surface of TH2 cells and not on TH1 cells (4). Therefore, IL-33 has been studied primarily for its role in the context of TH2 immunity and TH2-related diseases such as asthma, atopic dermatitis, and anaphylaxis (3,5-9). Recent studies, however, are beginning to show that IL-33 cytokine activities far exceed the realm of TH2 immunity by promoting TH1 immune responses and influencing the development of antiviral CD8+ T cells (10). In this review, we summarize recent studies describing how IL-33 is emerging as an important TH1 and CD8+ T cell-driving cytokine, essential for inducing protective cell-mediated immunity against cancer and chronic viral diseases.

IL-33: location and function

While historically isolated from keratinocytes, epithelial cells, and endothelial cells, IL-33 is now known to be released from a variety of tissue types as a pro-inflammatory cytokine (2,11). Specifically, IL-33 functions as an alarmin by signaling tissue damage to local immune cells after exposure to pathogens, injury-induced stress, or death by necrosis (11-15). IL-33 is predominantly expressed at the epithelial barrier as the first line of defense against pathogenic threats, activating a variety of cells: hematopoietic cells, mast cells, eosinophils, basophils, Natural Killer (NK) cells, Natural Killer T (NKT) cells, CD8+ T cells, TH2 lymphocytes, and non-hematopoietic cells (10,16-23).

IL-33 can operate in at least two spaces—nuclear and extracellular—and in at least two forms—full-length IL-33 (proIL-33) and mature IL-33 (mtrIL-33) (24-26). The nuclear space is the exclusive domain of proIL-33, able to concentrate there via its amino terminus that contains a non-classical nuclear-localization sequence and a short chromatin-binding motif (27). This is where IL-33 is usually found; however, when released by inflammation or stimulation, proIL-33 is often digested into mtrIL-33, a form with a lower molecular weight (18-kDa). Unlike proIL-33, mtrIL-33 is not capable of localizing into the nucleus because it lacks the N-terminal nuclear-localization sequence. The processing and release of proIL-33 appears cell-type specific and several proteases are being identified to process proIL-33 into active, mature forms of IL-33 (3,28,29).

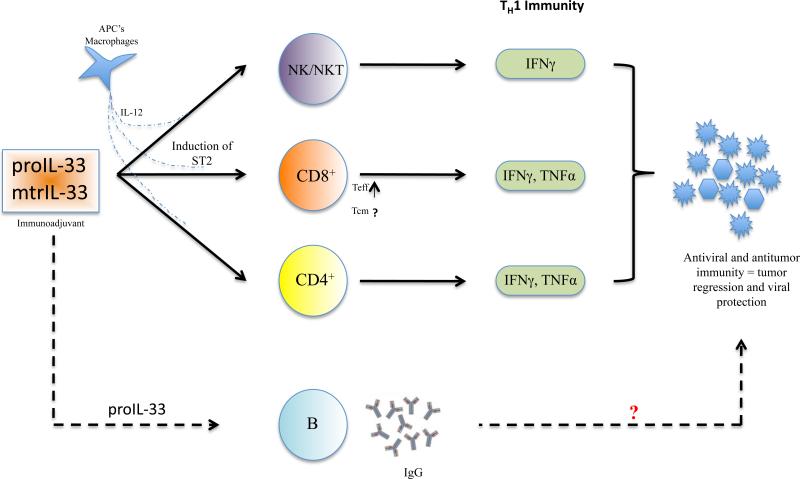

Currently, the nuclear function of proIL-33 is unclear, but recent studies have suggested it may play a role in transcriptional repression and chromatin compaction (24,30). Extracellular proIL-33 and mtrIL-33, on the other hand, are known to bind to their cognate receptor ST2, activating the MyD88-signaling pathway which induces the production of various cytokines and chemokines or causes cell differentiation, polarization, and activation, depending on the target cell (26,31). Although one might assume that they induce similar effects because they bind to the same ST2L, recent studies have reported that they have differences in their specific activities. Luzina et al. demonstrated that proIL-33 promotes inflammation differently from mtrIL-33 in an ST2-independent fashion (32). This study showed that compared to proIL-33, mtrIL-33 produced a strong TH2-skewing cytokine profile (32). To this, we recently reported that both isoforms delivered as vaccine immunoadjuvants could modulate the immune responses towards a TH1/CD8+ T cell response (Figure 1) (35). Under different conditions it appears that IL-33 can have different functions either associated in driving TH2- or TH1-immune responses when delivered in vivo (10,32,35). How one method elicits TH2 responses and another TH1 responses is unclear. Nevertheless, it is possible that different routes of delivery can have different outcomes. Moreover, we showed that proIL-33 delivered as a vaccine adjuvant was more potent at expanding the humoral immune response compared to mtrIL-33 (35). How proIL-33 and mtrIL-33 exert different effects on the humoral immune response is uncertain. It is likely that proIL-33 is not only an efficient agonist for ST2, but can also act independently of ST2 (32). This supports the theory that the immunomodulatory functions of IL-33 might actually be more complex than initially assumed. Additional studies are needed to elucidate the conditions under which proIL-33 and mtrIL-33 promote different cell-mediated immune responses and to determine the specific intracellular transcriptional targets of proIL-33 and mtrIL-33.

Figure 1.

Immunoadjuvant properties of administered full-length IL-33 (proIL-33) and/or mature IL-33 (mtrIL-33) on tumor and viral growth. These observed effects are determined by the specific cells targeted and the associated cytokine network. Administration of either proIL-33 or mtrIL-33 has been described as having cellular activities on NK/NKT, CD4+, and effector CD8+ T cells which produce Th1-associated protective immunity. Concomitantly, M1 macrophages and APCs produce and secrete IL-12, which then induces expression of ST2 on NK/NKT cells and CD8+ T cells, permitting IL-33 to induce Th1-associated cytokine production. It is unclear whether Th1 CD4+ T cells are able to upregulate ST2, however, IFNγ production by other activated immune cells likely leads to their amplification which then can help activate antiviral and tumoricidal immunity. Interestingly, recent evidence hints at a new activity for proIL-33 as it has been found to elicit antigen-specific antibodies, yet its role in protection against infectious pathogens remains to be determined. Notes: APC, antigen-presenting cells; NK, natural killer cells; NKT, natural killer T cells; Teff, effector memory CD8 T cells; Tcm, central memory CD8 T cells

IL-33: role in antiviral-protective immunity

Multiple groups have shown that IL-33 activity is primarily associated in driving TH2- immune responses, particularly in augmenting cytokine levels of IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 (33). However, it is now beginning to surface that IL-33 has functions that surpass TH2 immunity as it can contribute to the development of TH1-type immune responses and promote CD8+ T cell responses (Table 1).

Table 1.

The biological effects of IL-33 isoforms on T cells

| IL-33 Isoforms | Host | Biologically Active | T cell subsets | Specific effects | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full-length IL-33 | Human/mouse | Yes | TH2 cells | IL-4, IL-10, IL5 & IL-13 production, chemoattraction | 3,16,31,36 |

| TH1 cells | IFNγ, TNFα production | 35 | |||

| CD8+ cells | IFNγ, TNFα production, CTL activity, expansion and differentiation, chemoattraction, Tbet and Blimpl induced; NK-κB activation | 35,37 | |||

| Mature IL-33 | Human/mouse | Yes | TH2 cells | IL-4, IL-10, IL5 & IL-13 production, chemoattraction | 16,31,32,36,38,39,40 |

| TH1 cells | IFNγ, TNFα production | 35 | |||

| CD8+ cells | IFNγ & TNFα production, CTL phenotype | 10,34,38 | |||

Notes: CTL, cytotoxic T lmphocyte; NK-κB, nuclear factor kappa-B

Given its ability to direct these TH1-type immune responses, it is reasonable to discuss if IL-33 may also be essential in inducing protective immunity against viral infections. Some of the 1st studies to implicate IL-33's pro-TH1 cytokine activities observed its biological target on NKT cells (16,23). These studies showed that exposure to IL-33 privileged the production of IFNγ by NKT cells in response to TCR engagement and in the presence of IL-12. More recently, several studies have shown that this activity was not restricted to NKT cells. Yang et al. showed that CD8+ T cells can also express ST2 and respond to IL-33 (34). They reconfirmed the notion that IL-33 synergizes with TCR and/or IL-12 signaling to augment IFNγ production in effecter CD8+ T cells (34). Consistent with these findings, Bonilla et al. showed that following LCMV infection in mice, roughly 20% of activated antigen (Ag)-specific CD8+ T cells expressed ST2 (10). This study provided evidence for the first time that IL-33 can drive protective antiviral CD8+ T cell responses in vivo. However, it remains to be answered why only 20% of the activated CD8+ T Cells expressed ST2? Are these a unique subset of CD8+ T cells that expresses or upregulates ST2? Additionally, we recently showed that IL-33 can orchestrate protective antiviral CTL responses, expand the magnitude of Ag-specific CD8+ T cells responses, and enhance the production of TNFα and IFNγ responses (35). Interestingly, this study showed that both isoforms of IL-33 (proIL-33 and mtrIL-33) can act as immunoadjuvants to induce potent viral-specific TH 1 CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses (35). Notably, our recent finding challenges the prevailing opinion that IL-33 strictly targets TH2 CD4+ T cells, as we now know it has the potential to target TH1 cell-mediated T cells. Interestingly, the delivery of IL-33 did not enhance IL-4 or immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels, which is in contrast to the previously observed effects of IL-33. This provides further evidence that under certain conditions, IL-33 exhibits different immunological properties (depending on the type of activated cells and the microenvironment). Together, these studies give insight into IL-33's new biological activity to direct TH1 and effector CD8+ T cells and its essential role in driving protective immunity against viral pathogens. Although certain immunoadjuvants have been shown to enhance the potency of vaccines by inducing TH1, it has been a challenge to find adjuvants that can also facilitate CD8+ T cell responses. Thus, the demonstration that IL-33 can induce both Ag-specific TH1 and CD8+ T cell responses in preclinical settings makes IL-33 an ideal adjuvant candidate for enhancing prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines (Figure 1). Such vaccines could target an array of microbial infections, especially intracellular pathogens, and cancer, where T cell-mediated immunity is crucial for protection.

IL-33: role in antitumor immunity

There is a plethora of studies about the pleiotropic cytokine activities of IL-33 and its role in inflammation and its association with allergy and autoimmune diseases (33,36). However its role in antitumor immunity and antitumor growth is only beginning to surface. Given the recent studies (as mentioned above) showing that IL-33 can augment Ag-specific TH1 and CD8+ T cell immune responses, its role in enhancing tumor surveillance and antitumor immunity is worth continued investigation.

Two recent studies have highlighted the important role of IL-33 in experimental mouse tumor models and have shown that IL-33 can drive antitumor CD8+ T cell responses. Gaoet al. used B16 melanoma and Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) metastatic models to show that transgenic expression of IL-33 inhibited tumor growth and metastasis in mice (37). Transgenic expression of IL-33 and delivery of recombinant IL-33 increased the infiltration of CD8+ T cells and NK cells into the tumor and also increased their cytotoxicity both in vitro and in vivo (37). This study provides further evidence that IL-33 promotes the proliferation and activation of CD8+ T cells and NK cells by activating the intracellular molecule nuclear factor-κb (NF-κb) and suggests a mechanism by which IL-33 might promote CD8+ and NK activation and expansion. We, ourselves, have recently shown—using an HPV-associated mouse tumor model—that two isoforms of IL-33 delivered as immunoadjuvants induced potent antitumor immunity and rapidly caused complete regression of established TC.1 tumor-bearing mice (35). Administration of IL-33 skewed T cell responses towards the TH1 axis, enhancing potent Ag-specific effector and memory T cell responses. Crucially, using the P14 transgenic mouse model, we showed that IL-33 can significantly generate effector-memory CD8+ T cells in the periphery, correlating with the rapid and complete regression of established tumors (35). More studies are needed to define the molecular mechanisms of how IL-33 influences the differentiation and expansion of the CD8+ T cells responses (Figure 1). Together, these data demonstrate the notion that IL-33 increases the formation of Ag-specific CD8+ T cells and reveals that IL-33 has immunotherapeutic implications in driving immune responses against cancer (Figure 1). Overall, further investigation is needed to define IL-33 specific roles in the tumor surveillance process.

Concluding remarks

IL-33 has emerged as a switch-hitting cytokine adjuvant: a multi-talented immune player that promotes both TH2 and TH1 immune responses given the right type of immune cells activated, the microenvironment, and the cytokine milieu. As such, IL-33 may play different roles in different diseases based on the details of expression and delivery. Clearly in this regard, IL-33 as an immune therapeutic gene warrants further investigation. How IL-33 regulates the humoral immunity or enhances the generation and maintenance of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells remain important questions. Further studies to define details of the function of IL-33 in the nucleus and to understand its synthesis, processing, and release will provide important areas for targeted therapeutics in both infectious diseases as well as cancer immune therapy. The accessibility of both ST2 and IL-33 knockout mice will allow for investigation regarding the biological function of all isoforms of IL-33; enhancing our understanding of IL-33's ability to influence adoptive immunity and its power to protect against disease. This exciting evidence that IL-33 can induce antiviral and antitumor responses validates IL-33 as a potent new adjuvant in vaccinations.

Highlights.

IL-33 is a proinflammtory cytokine with pleiotropic properties

IL-33 activities far exceed the Th2 immunity also promoting Th1 and CD8 responses

IL-33 can drive antiviral and antitumor immunity

IL-33 can act as a new potent immunoadjuvant

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Rebekah Joy Siefert for critical reading and editing of the manuscript. DBW notes funding by the National Institutes of Health (U19-A1078675), Basser Research Center for BRCA, and by Inovio Pharmaceuticals. The authors also thank Penn CFAR and ACC core facilities for their support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

D.B.W. has grant funding, participates in industry collaborations, has received speaking honoraria, and fees for consulting. This service includes serving on scientific review committees and advisory boards. Remuneration includes direct payments or stock or stock options and in the interest of disclosure therefore he notes potential conflicts associated with this work with Pfizer, Inovio, Merck, VGXI, OncoSec, Roche, Aldevron, and possibly others. Licensing of technology from his laboratory has created over 100 jobs in the biotech/pharma industry. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Onda H, Kasuya H, Takakura K, Hori T, Imaizumi T, Takeuchi T, Inoue I, Takeda J. Identification of genes differentially expressed in canine vasospastic cerebral arteries after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:1279–1288. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199911000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baekkevold ES, Roussigne M, Yamanaka T, Johansen FE, Jahnsen FL, Amalric F, Brandtzaeg P, Erard M, Haraldsen G, Girard JP. Molecular characterization of NF-HEV, a nuclear factor preferentially expressed in human high endothelial venules. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:69–79. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63631-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3•.Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, Song Y, Murphy E, McClanahan TK, Zurawski G, Moshrefi M, Qin J, Li X, et al. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23:479–490. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015. [The first study that identified IL-33.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4•.Xu D, Chan WL, Leung BP, Huang Fp, Wheeler R, Piedrafita D, Robinson JH, Liew FY. Selective expression of a stable cell surface molecule on type 2 but not type 1 helper T cells. J Exp Med. 1998;187:787–94. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.5.787. [The first study to show that selective expression of ST2 on TH2, but not TH1 cells.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pushparaj PN, Tay HK, H'Ng SC, Pitman N, Xu D, McKenzie A, Liew FY, Melendez AJ. The cytokine interleukin-33 mediates anaphylactic shock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9773–9778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901206106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 6.Matsuba-Kitamura S, Yoshimoto T, Yasuda K, Futatsugi-Yumikura S, Taki Y, Muto T, et al. Contribution of IL-33 to induction and augmentation of experimental allergic conjunctivitis. Int Immunol. 2010;22:479–89. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rankin AL, Mumm JB, Murphy E, Turner S, Yu N, McClanahan TK, Bourne PA, Pierce RH, Kastelein R, Pflanz S. IL-33 induces IL-13-dependent cutaneous fibrosis. J Immunol. 2010;184:1526–1535. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hazlett LD, McClellan SA, Barrett RP, Huang X, Zhang Y, Wu M, et al. IL-33 shifts macrophage polarization, promoting resistance against Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:1524–32. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solarski B, Kurowska-Stolarska M, Kewin P, Xu D, Liew FY. IL-33 exacerbates eosinophil-mediated airway inflammation. J Immunol. 2010;185:3472–3480. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10••.Bonilla WV, Frohlich A, Senn K, Kallert S, Fernandez M, Johnson S, et al. The alarmin interleukin-33 drives protective antiviral CD8(+) T cell responses. Science. 2012;335:984–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1215418. [The first direct in vivo demonstration that IL-33 is important in controlling mice against viral infection by inducing effective CD8+ T cell responses.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moussion C, Ortega N, Girard JP. The IL-1-like cytokine IL-33 is constitutively expressed in the nucleus of endothelial cells and epithelial cells in vivo: a novel ‘Alarmin’? Plos One. 2008:3. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kakkar R, Hei H, Dobner S, Lee RT. Interleukin 33 as a mechanically responsive cytokine secreted by living cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:6941–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.298703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13•.Cayrol C, Girard JP. The IL-1-like cytokine IL-33 is inactivated after maturation by caspase-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9021–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812690106. [This study reports that full-length IL-33 is biologically active and is released upon cellular damage.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luthi AU, Cullen SP, McNeela EA, Duriez PJ, Afonina IS, Sheridan C, et al. Suppression of interleukin-33 bioactivity through proteolysis by apoptotic caspases. Immunity. 2009;31:84–98. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haraldsen G, Balogh J, Pollheimer J, Sponheim J, Küchler AM. IL33-cytokine of dual function or novel alarmin? Trends immunol. 2009;30:227–33. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smithgall MD, Comeau MR, Yoon BR, Kaufman D, Armitage R, Smith DE. IL-33 amplifies both Th1- and Th2-type responses through its activity on human basophils, allergen-reactive Th2 cells, iNKT and NK cells. Int Immunol. 2008;20:1019–30. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pecaric-Petkovic T, Didichenko SA, Kaempfer S, Spiegl N, Dahinden CA. Human basophils and eosinophils are the direct target leukocytes of the novel IL-1 family member IL-33. Blood. 2009;113:1526–34. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-157818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moulin D, Donze O, Talabot-Ayer D, Mezin F, Palmer G, Gabay C. IL-33 induces the release of pro-inflammatory mediators by mast cells. Cytokine. 2007;40:216–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzukawa M, Iikura M, Koketsu R, Nagase H, Tamura C, Komiya A, Nakae S, Matsushima K, Ohta K, Yamamoto K, Yamaguchi M. An IL-1 cytokine member, Il-33 induces human basophil activation via its ST2 Receptor. J Immunol. 2008;81(9):5981–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.5981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cherry WB, Yoon J, Bartemes KR, Lijima K, Kita H. A novel IL-1 family cytokine, Il-33, potently activates human eosinophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1484–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider E, Petit-Bertron AF, Bricard R, Levasseur M, Ramadan A, Girard JP, Herbelin A, Dy M. IL-33 activates unprimed murine basophils directly in vitro and induces their in vivo expansion indirectly by promoting hematopoietic growth factor production. J Immunol. 2009;183:3591–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rank MA, Kobayashi T, Kozaki H, Bartemes KR, Squillace DL, Kita H. IL-33-activated dendritic cells induce an atypical TH2-type response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1047–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bourgeois E, Van LP, Samson M, Diem S, Barra A, Roga S, et al. The pro-Th2 cytokine IL-33 directly interacts with invariant NKT and NK cells to induce IFN-gamma production. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:1046–55. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24•.Carriere V, Roussel L, Ortega N, Lacorre DA, Americh L, Aguilar L, et al. IL-33, the IL-1-like cytokine ligand for ST2 receptor, is a chromatin-associated nuclear factor in vivo. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:282–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606854104. [This study suggests that the function of full-length IL-33 in the nucleus acts as a transcriptional repressor.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Talabot-Ayer D, Lamacchia C, Gabay C, Palmer G. IL-33 is biologically active independently of caspase-1 cleavage. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19420–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901744200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michael MU. Special aspects of Interleukin-33 and the IL-33 receptor complex. Semin Immunol. 2013;25:449–57. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmer G, Gabay C. Interleukin 33 biology with potential insights into human diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:321–9. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayakawa M, Hayakawa H, Matsuyama Y, Tamemoto H, Okazaki H, Tominaga S. Mature Interleukin-33 is produced by calpain-mediated cleavage in vivo. Biocjem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;387:218–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lefrancais E, Roga S, Gautier V, Gonzalez-de-Peredo A, Monsarrat B, Girard JP, et al. IL-33 is processed into mature bioactive forms by neutrophil elastase and cathepsin G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:1673–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115884109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roussel L, Erard M, Cayrol C, Girard JP. Molecular mimicry between IL-33 and KSHV for attachment to chromatin through the H2A-H2B acidic pocket. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:1006–12. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kakkar R, Lee RT. The IL-33/ST2 pathway: therapeutic target and novel biomarker. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:827–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luzina IG, Pickering EM, Kopach P, Kang PH, Locatell V, Todd NW, Papadimitriou JC, McKenzie AN, Atamas SP. Full-length IL-33 promotes inflammation but not Th2 response in vivo in an ST2-independent fashion. J Immunol. 2012;189:403–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liew FY, Pitman NI, McInnes IB. Disease-associated functions of IL-33: the new kid in the IL-1 family. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:103–10. doi: 10.1038/nri2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34••.Yang Q, Li G, Zhu Y, Liu L, Chen E, Turnquist H, et al. IL-33 synergizes with TCR and IL-12 signaling to promote the effector function of CD8(+) T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:3351–60. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141629. [The first report to show in vitro that activated CD8+ T cells can respond to IL-33 and further encourages the interest of IL-33 unappreciated role at enhancing TH1 and CD8+ T cell immunity.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35••.Villarreal DO, Wise MC, Walters JN, Reuschel E, Choi MJ, Obeng-Adjei N, Yan J, Morrow MP, Weiner DB. Alarmin IL-33 acts as an immunoadjuvant to enhance antigen-specific tumor immunity. Caner Res. 2014 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2729. Epub ahead of print. [The first study to show that two isoforms of IL-33 delivered as endogenous adjuvants can induce in vivo antitumor immunity. Study also reaffirms that IL-33 can orchestrate protective antiviral CTL responses.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller AM. Role of IL-33 in inflammation and disease. J Inflamm (Lond) 2011;8:22. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao K, Li X, Zhang L, bai L, Dong W, Gao K, Shi G, Xia X, Wu L, Zhang L. Transgenic expression of IL-33 activates CD8(+) T cells and NK cells and inhibits tumor growth and metastasis in mice. Cancer Lett. 2013;335:463–71. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Komai-Koma M, Xu D, Li Y, McKenzie AN, McInnes IB, Liew FY. IL-33 is a chemoattractant for human Th2 cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2007;37:2779–2786. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurowska-Stolarska M, Kewin P, Murphy G, Russo RC, Stolarski B, Garcia CC, Komai-Koma M, Pitman N, Li Y, Niedbala W, McKenzie AN, Teixeira MM, Liew FY, Xu D. IL-33 induces antigen-specific IL-5+ T cells and promotes allergic-induced airway inflammation independent of IL-4. J Immunol. 2008;181:4780–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo L, Wei G, Zhu J, Liao W, Leonard WJ, Zhao K, Paul W. IL-1 family members and STAT activators induce cytokine production by Th2, Th17, and Th1 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13463–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906988106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]