Abstract

Stiffening of the central elastic arteries is one of the earliest detectable manifestations of adverse change within the vessel wall. While an association between carotid artery stiffness and adverse events has been demonstrated, little is known about the relationship between stiffness and atherosclerosis. Even less is known about the impact of age, gender, and race on this association. To elucidate this question, we used baseline data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA, 2000-2002). Carotid artery distensibility coefficient (DC) was calculated after visualization of the instantaneous waveform of common carotid diameter using high resolution B-mode ultrasound. Thoracic aorta calcification (TAC) was identified using non-contrast cardiac CT. We found a strong association between decreasing DC (increasing carotid stiffness) and increasing TAC as well as a graded increase in TAC score (p<0.001). After controlling for age, gender, race, and traditional and emerging cardiovascular risk factors, individuals in the stiffest quartile had a prevalence ratio of 1.52 (95% CI 1.15-2.00) for TAC compared to the least stiff quartile. In exploratory analysis, carotid stiffness was more highly correlated with calcification of the aorta than calcification of the coronary arteries (ρ=0.32 vs. 0.22, p<0.001 for comparison). In conclusion, there is a strong independent association between carotid stiffness and thoracic aorta calcification. Carotid stiffness is more highly correlated with calcification of the aorta, a central elastic artery, than calcification of the coronary arteries. The prognostic significance of these findings requires longitudinal follow-up of the MESA cohort.

Keywords: Carotid stiffness, carotid compliance, subclinical atherosclerosis, thoracic aorta calcification, coronary calcification

Introduction

Stiffening of the central elastic arteries is one of the earliest detectable manifestations of adverse change within the vessel wall1, 2. Accompanying decreased arterial compliance is closely associated with aging3 and other traditional cardiovascular risk factors4, 5. Measures of central artery stiffness, including aortic pulse wave velocity6, have been associated with coronary artery disease7-9, congestive heart failure10, 11, stroke12, as well as all-cause mortality13-15. Although aortic and systemic stiffness have proven difficult to apply in the clinical setting, local stiffening within the carotid artery remains appealing because it is more directly accessible to measurement.

Mechanical properties of the carotid arteries are mostly easily visualized using high resolution ultrasound16. On a real-time sweep of the common carotid artery, dynamic measurements of carotid diameter can be made that enable calculation of several indices of stiffness: distensibility coefficient (DC), Young's elastic modulus (YM), β stiffness index, and carotid distension17. These indices have been shown to predict coronary heart disease and stroke amongst apparently healthy individuals in the Rotterdam18 and Three-City studies19.

Despite the association between carotid stiffness and poor outcomes, little is known about the association between stiffness and atherosclerosis. Even less is known about the impact of age, gender, and race on this association. The little available data correlating carotid stiffness with aortic atherosclerosis used plain radiography of the abdomen as the measure of plaque burden20. Definitive conclusions have been limited by the use of this insensitive and difficult-to-quantify measure of atherosclerosis. In contrast, measurement of arterial calcification by computed tomography (CT) allows quantification of the volumetric burden of atherosclerosis, including that found within the more central ascending and descending thoracic aorta21.

To better describe the association between stiffness and atherosclerosis, we assessed the cross-sectional association between carotid DC measured with ultrasound and thoracic aortic calcification (TAC) measured by CT in a large multi-ethnic cohort. In further analysis, we looked for regional variability in the association between carotid stiffness and calcification in the aorta (an elastic central artery) and the coronary arteries (peripheral arteries).

Methods

Study Design and Patient Population

We used baseline data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA, 2000-2002). The MESA study design, patient recruitment and selection have been previously described22. In summary, MESA enrolled 6,814 asymptomatic men and women of 4 different ethnic groups (Whites, Chinese, African-American, and Hispanic), aged 45 to 84, into a population-based prospective cohort study aimed at describing the prevalence, progression, and significance of subclinical atherosclerosis. Patients were drawn from 6 geographically distinct population centers in the United States. All patients were free of known cardiovascular disease at enrollment.

Each MESA participant underwent 2 baseline cardiac CT scans for the evaluation of coronary and extra-coronary calcification. In 6,529 (96%) participants, baseline carotid ultrasound imaging was sufficient to calculate DC. Patients without sufficient carotid imaging were more likely to be female and African-American, but did not differ in age or any other measured covariate. All participants gave informed consent for the study protocol, which was approved by the institutional review boards of all 6 MESA field centers.

Carotid Imaging and Distensibility Coefficient

The right and left carotid arteries were imaged according to a common scanning protocol using high resolution B-mode ultrasonography with a Logiq 700 machine (General Electric Medical Systems). Carotid IMT was measured in the common carotid artery, and reported as the mean of the maximum IMT measured in the right and left sides for both the near and far walls. Data necessary for calculating DC were obtained from a separate 20 second-long acquisition of longitudinal images of the right distal common carotid artery. All images were interpreted at a central MESA ultrasound reading center (Tufts Medical Center) by readers blinded to all clinical information.

For each participant, an edge detector was used to process the images and extract carotid arterial diameter curves. Diastolic and systolic diameters were determined as the smallest and largest diameter values during a cardiac cycle. Blood pressure measurements were taken by upper arm sphygmomanometry (DINAMAP system, GE Medical Systems) at the time of the carotid artery ultrasound.

These data were used to calculate a simplified DC via the following equations described by Gamble23:

Where ΔD is the change in systolic/diastolic diameter, ΔP is the brachial pulse pressure, Ds is the systolic diameter, D is the average common carotid artery diameter, and h is the, mean wall thickness (IMT) measured 10 mm proximal to the carotid bulb.

Reproducibility studies were performed in 221 participants; 211 were intraobserver repeated image analyses, and 10 interobserver correlations. For DC and YM, the intraobserver class correlation coefficient (ICC) was 0.71 and 0.69, respectively. The interobserver ICC was 0.85 and 0.84, respectively. The intraobserver variability in reading exams was assessed in 204 patients, revealing an ICC of 0.68 for DC and 0.80 for YM. This reflects good to excellent agreement.

Cardiac CT protocol

Cardiac CT was performed at 3 sites using a cardiac-gated electron-beam CT scanner (Imatron C-150XL, GE-Imatron, San Francisco, CA), and at 3 sites using 4-slice multidetector CT. All participants were scanned over phantoms of known physical calcium concentration. Images were read at the MESA CT reading center (Harbor-UCLA).

The MESA scanning protocol has been described previously24. Images slices were obtained with the participant supine, with no couch angulation, during a single breath hold. A minimum of 35 contiguous images were obtained, beginning above the left main coronary artery and proceeding below both ventricles. Section thickness of 3 mm, field of view 35 cm, and matrix 512 × 512 were used to reconstruct the raw data. Nominal section thickness was 3.0 mm for electron beam CT and 2.5 mm for 4-detector row CT. Spatial resolution, expressed as the smallest voxel able to be discriminated, was 1.38 mm3 (0.68 × 0.68 × 3.00 mm) for electron beam CT and 1.15 mm3 (0.68 × 0.68 × 2.50 mm) for 4-detector row CT.

The ascending and descending thoracic aorta was visualized from the lower edge of the pulmonary artery bifurcation to the cardiac apex on each cardiac CT. TAC is defined as total calcification in the ascending + descending portions. For this study, TAC is considered both as a binary measure (present vs. not present) and a continuous measure (Agatston score).

The reproducibility of extracoronary measures of calcification within MESA has been discussed in detail previously25. To summarize for TAC, among 1,729 randomly chosen participants undergoing rescanning on dual scanners, the intra-scan kappa statistic for agreement on presence of TAC was 0.95 (0.94 – 0.97). This varied slightly by scanner type, with MDCT outperforming EBCT (0.97 vs. 0.94). The mean rescan percentage absolute difference in Agatston score for measurement of TAC>0 was 10.2%. This variability is most likely due to slightly different starting points for the two scans, such that that slightly different anatomy may be examined in scan 1 and scan 2. The reproducibility of CAC within MESA has also been thoroughly described26. The kappa statistic for agreement on presence of CAC was 0.92, and the mean rescan percentage absolute difference in CAC>0 was 20.1%.

Study Covariates

Hypertension, smoking, diabetes, and family history of heart attack are presented as binary variables. Hypertension was defined as use of anti-hypertensive medication or baseline sphygmomanometric measurements of blood pressure fulfilling Joint National Committee (JNC) guidelines (≥140/90 mmHg identifying hypertension). Smoking was defined as prior or present use of tobacco cigarettes. Diabetes was defined according to American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines (fasting blood sugar >126 mg/dL) or the use of hypoglycemic medications. Replacement of hypertension, smoking, and diabetes with absolute systolic and diastolic blood pressure, pack-years of smoking, and fasting blood glucose in the study models resulted in minimal change with no overall impact on study conclusions. Medication use was defined as present use of prescription medications for the treatment of hypertension or hypercholesterolemia. Family history was positive if an immediate family member (parents, siblings, or children) had suffered a heart attack.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of the study participants are presented over decreasing quartiles of distensibility coefficient (increasing carotid stiffness). The 4th quartile (most distensible) is used as the reference group for subsequent analyses. Frequencies and proportions are reported for categorical variables, and either means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges are reported for continuous variables based on normality of distribution. Chi-square tests, Fisher's exact tests, one-way ANOVA, or Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for comparison of variables between groups.

Because the prevalence of CAC in our cohort is greater than 10%, odds ratios (ORs) overestimate relative risk. Therefore, prevalence ratio estimates are presented from the regression model y=exp(XTβ), with the exponentiated parameter β interpreted as the relative risk or prevalence ratio. Using this method we assessed the relationship between DC and presence of TAC, in a hierarchal fashion. Model 1 adjusts for key demographic variables: age, gender, and race. Model 2 adds traditional and emerging cardiovascular risk factors: body mass index, heart rate, LDL cholesterol, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cigarette smoking, family history of heart attack, and lipid-lowering medication use. Model 3 adds the inflammatory variable C-reactive protein and baseline measures of subclinical vascular disease: coronary artery calcium (CAC), and carotid IMT.

To better discern the influence of important study covariates, additional stratified analyses were conducted, with results are expressed as the prevalence ratio of having TAC per one standard deviation increase in DC. Finally, to explore differential correlations between DC and calcification of thoracic aorta and coronary arteries, we constructed a Spearman correlation coefficient matrix between DC, TAC, and CAC. We used logarithmically transformed values of TAC and CAC (ln [score +1]) to normalize their distributions.

All analyses used a 5% two-sided significance level. Calculations were performed using STATA software, version 8.2.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of the MESA participants

The mean age of the 6,526 study participants was 62 ± 10 years. Approximately 53% were male, with mean calculated 10-year Framingham risk for the entire cohort of 8.2 ± 7%. Mean DC for the study cohort was 2.51 mmHg, with standard deviation 1.1 mmHg × 10-3. Median DC was 2.36 mmHg × 10-3 reflecting slight rightward skew. The mean and median DC values are similar to those reported in other studies after adjusting for differences in calculation18.

Patients were divided into 4 categories based on their values for DC (See Table 1). Across decreasing DC quartiles (increasing carotid stiffness), patients were on average older, more likely to be female, and enriched in the African-American and Hispanic ethnicities. Most traditional and emerging cardiac risk factors were associated with decreasing DC, including body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, diabetes, smoking, and C-reactive protein (CRP). In addition, decreasing DC was associated with a higher prevalence of CAC, a higher CAC score, and lower carotid IMT (all p<0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants.

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index, Cr = creatinine, CRP = C-reactive protein, CAC = coronary artery calcium, FRS = Framingham Risk Score.

| Characteristic | Total (N = 6,526) | DC Quartile 4 (≥3.02) | DC Quartile 3 (2.36-3.01) | DC Quartile 2 (1.78-2.35) | DC Quartile 1 (≤1.77) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 62 ± 10 | 55 ± 8 | 60 ± 9 | 64 ± 9 | 69 ± 9 | <0.001 |

| Gender, women | 53% | 51% | 50% | 54% | 56% | 0.001 |

| Race | ||||||

| ▪ Whites | 39% | 46% | 42% | 37% | 29% | <0.001 |

| ▪ Chinese | 12% | 11% | 14% | 12% | 12% | |

| ▪ African American | 27% | 23% | 32% | 29% | 35% | |

| ▪ Hispanic | 22% | 21% | 21% | 23% | 24% | |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 63 ± 10 | 61 ± 9 | 63 ± 9 | 64 ± 10 | 65 ± 11 | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.3 ± 5 | 27.3 ± 5 | 28.1 ± 5 | 28.9 ± 6 | 28.8 ± 5 | 0.022 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 127 ± 22 | 114 ± 16 | 122 ± 17 | 129 ± 19 | 142 ± 23 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 72 ± 10 | 69 ± 10 | 71 ± 9 | 73 ± 10 | 75 ± 11 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 45% | 22% | 35% | 51% | 71% | <0.001 |

| Fasting glucose | 104 ± 31 | 99 ± 29 | 102 ± 26 | 106 ± 32 | 110 ± 35 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 14% | 8% | 12% | 15% | 22% | <0.001 |

| Cr, mg/dL | 0.95 ± 0.3 | 0.93 ± 0.2 | 0.94 ± 0.3 | 0.95 ± 0.3 | 0.99 ± 0.3 | <0.001 |

| Smoking | <0.001 | |||||

| ▪ Former | 37% | 34% | 36% | 38% | 39% | |

| ▪ Current | 13% | 21% | 13% | 10% | 8% | |

| LDL, mg/dL | 117 ± 32 | 117 ± 32 | 112 ± 31 | 118 ± 32 | 116 ± 32 | 0.61 |

| HDL, mg/dL | 51 ± 15 | 51 ± 15 | 50 ± 14 | 51 ± 15 | 51 ± 15 | 0.27 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 111 (77 – 161) | 102 (72 – 152) | 115 (79 – 166) | 113 (80 – 163) | 114 (81 – 162) | <0.001 |

| Family history of heart attack | 40% | 40% | 41% | 41% | 39% | 0.67 |

| Medications for hypertension | 37% | 22% | 32% | 42% | 53% | <0.001 |

| Medications for cholesterol | 16% | 11% | 15% | 18% | 19% | <0.001 |

| hsCRP, mg/L | 1.90 (0.83 – 4.19) | 1.56 (0.66 – 3.88) | 1.71 (0.76 – 3.80) | 2.07 (0.94 – 4.46) | 2.25 (0.99 – 4.61) | <0.001 |

| CAC | 50% | 36% | 47% | 53% | 63% | <0.001 |

| Ln (CAC+1), (score) | 2.19 ± 2.5 | 1.42 ± 2.2 | 2.03 ± 2.5 | 2.38 ± 2.6 | 2.94 ± 2.6 | <0.001 |

| Carotid IMT, mm | 0.87 ± 0.19 | 0.80 ± 0.16 | 0.84 ± 0.18 | 0.89 ± 0.19 | 0.95 ± 0.21 | <0.001 |

| 10-yr FRS (%) | 8.2 ± 7% | 5.6 ± 6% | 7.3 ± 7% | 8.7 ± 7% | 12 ± 8% | <0.001 |

Prevalence of TAC by DC Quartile

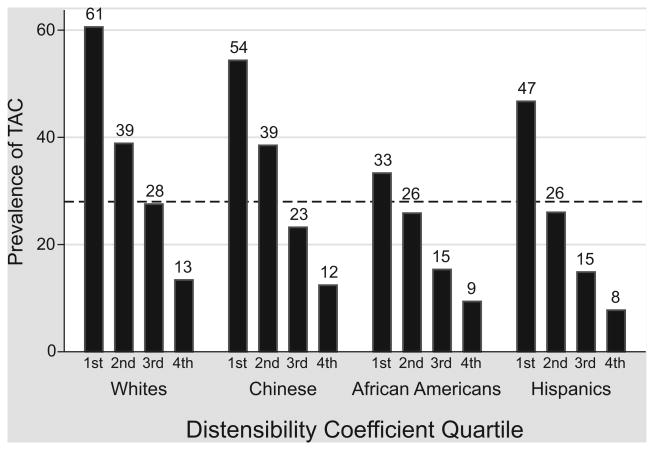

The prevalence of TAC was 28% for the study cohort. Across all four ethnicities, there was a graded association between increasing DC quartile and decreasing prevalence of TAC (p<0.001, See Figure 1). The prevalence of TAC reached 61% among whites for quartile 1, the group with the stiffest arteries. The association between DC and TAC remained strong among African-Americans, the ethnicity known to have the lowest incidence of TAC.

Figure 1.

Unadjusted prevalence of thoracic aorta calcium (TAC) by increasing distensibility coefficient quartile, stratified by race.

Calcification of the aorta decreased with increasing carotid distensibility. Overall prevalence of TAC is 28% (dotted line). p<0.001 in each race for the trend across DC quartiles.

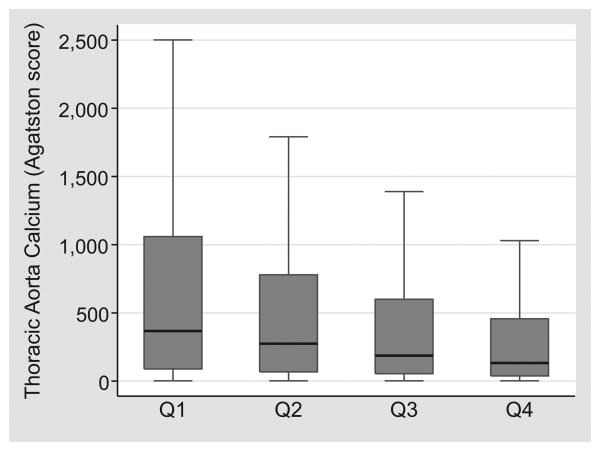

Association between DC and TAC Score

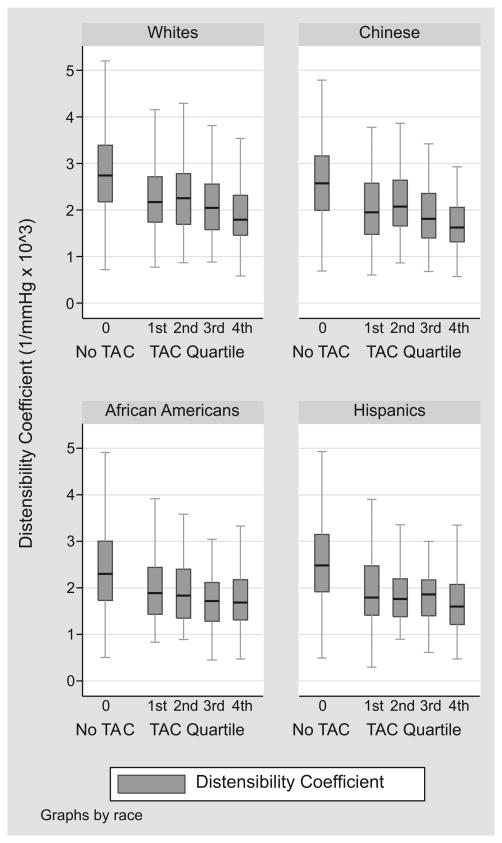

Considering only patients with prevalent TAC (score > 0), there remains a “dose-response” relationship between DC quartile and TAC score (See Figure 2). From the least to the most distensible carotid artery quartile, the median TAC scores were 367, 275, 187, and 133 respectively (p<0.001). To better demonstrate this graded relationship, we examined median DC over quartiles of TAC score, retaining the large TAC=0 group as a distinct category (See Figure 3). Across all races, mean DC was higher among patients with no TAC (p<0.001), with a modest threshold effect for lower DC among individuals in the highest TAC score quartile. In linear aggression analysis adjusting for age, race, and gender, one standard deviation decrease in DC corresponded to a 12% relative increase in log-transformed TAC score (p=0.008).

Figure 2.

Median, interquartile range, and adjacent values of thoracic aorta calcium (TAC) by distensibility coefficient (DC) quartile in those with TAC>0.

In those with TAC, the mean TAC score decreased with increasing distensibility of the carotid artery. P<0.001 for the association across DC quartiles.

Figure 3.

Median, interquartile range, and adjacent values of distensibility coefficient by absence/quartiles of thoracic aortic calcium

Carotid distensibility is greatest in those with no TAC, with a threshold effect for decrease distensibility among individuals in the highest TAC score quartile. P<0.001 for the association across all TAC groups

Multivariable Regression Models

The results from three different regression models are presented in Table 2. Adjusted for demographic variables, the prevalence ratio for having TAC amongst the least distensible compared to the most distensible quartile was 1.79 (95% CI 1.41 – 2.26). Adding cardiovascular risk factors to the model, the prevalence ratio was slightly attenuated to 1.52 (95% CI 1.19 – 1.96). Adding measures of subclinical vascular disease resulted in little change, with prevalence ratio 1.52 (95% CI 1.15 – 2.00). Additional analyses including creatinine and fasting glucose into the model did not change these results.

Table 2.

Multivariable-adjusted prevalence ratio (95% CI) for thoracic aorta calcium by decreasing quartile of distensibility coefficient.

| Prevalence Ratio for TAC | Distensibility Coefficient (decreasing quartiles, in 1/mmHg × 103) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

|

Quartile 4 (≥3.02) |

Quartile 3 (2.36-3.01) |

Quartile 2 (1.78-2.35) |

Quartile 1 (≤1.77) |

|

| Model 1 | 1 (ref group) | 1.15 (0.90-1.47) | 1.50 (1.19-1.89) | 1.79 (1.41-2.26) |

| Model 2 | 1 (ref group) | 1.17 (0.91-1.50) | 1.43 (1.13-1.83) | 1.52 (1.19-1.96) |

| Model 3 | 1 (ref group) | 1.24 (0.95-1.64) | 1.43 (1.09-1.87) | 1.52 (1.15-2.00) |

Model 1: Adjusted for age, gender, and race

Model 2: Model 1 + body mass index, heart rate, LDL cholesterol, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cigarette smoking, family history of heart attack, cholesterol-lowering medications

Model 3: Model 2 + log transformed C-reactive protein, log transformed CAC+1, carotid IMT

Table 3 show the results of stratified multivariable analyses examining the prevalence ratio for TAC with one standard deviation change in DC (See Table 3). For the entire cohort, one standard deviation decrease in distensibility coefficient resulted in 25% increase in TAC prevalence (95% CI 1.12 – 1.41). In stratified analyses, individual risk factors did not have a major impact on this association, with numerous statistically significant associations and overlapping confidence intervals. Associations between DC and TAC remained strong in middle-aged participants and individuals in the lower Framingham risk categories.

Table 3.

Prevalence ratio (95% CI) for thoracic aortic calcium with one standard deviation decrease in distensibility coefficient.

| Characteristic | N | N with TAC>0 | Relative Risk (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Tertile 1 (45-56 yo) | 2,239 | 107 | 1.58 (0.70 – 3.57) | 0.27 |

| Tertile 2 (57-67 yo) | 2,125 | 480 | 1.15 (0.97 – 1.36) | 0.10 |

| Tertile 3 (68-84 yo) | 2,162 | 1,239 | 1.33 (1.14 – 1.55)* | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||

| Females | 3,427 | 992 | 1.30 (1.10 – 1.54)* | 0.002 |

| Males | 3,099 | 834 | 1.21 (1.03 – 1.41)* | 0.017 |

| Race | ||||

| Whites | 2,517 | 814 | 1.27 (1.10 – 1.47)* | 0.001 |

| Chinese | 783 | 252 | 1.24 (0.89 – 1.73) | 0.21 |

| African-American | 1,779 | 401 | 1.17 (0.85 – 1.61) | 0.34 |

| Hispanic | 1,447 | 359 | 1.32 (0.96 – 1.82) | 0.09 |

| Risk Factor Status | ||||

| Normotensive | 3.613 | 651 | 1.34 (1.14 – 1.58)* | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 2,913 | 1,175 | 1.21 (1.02 – 1.43)* | 0.03 |

| Non-Diabetic | 5,605 | 1,482 | 1.23 (1.09 – 1.39)* | 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 921 | 334 | 1.46 (1.10 – 1.94)* | 0.008 |

| Non-Smoker | 5,681 | 1,602 | 1.27 (1.12 – 1.45)* | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 845 | 224 | 1.22 (0.97 – 1.54) | 0.09 |

| Framingham Risk Score† | ||||

| Low (0-6%) | 2,890 | 414 | 1.30 (1.05 – 1.63)* | 0.02 |

| Intermediate (6-20%) | 2,570 | 806 | 1.21 (1.03 – 1.44)* | 0.03 |

| High (≥20%) | 1,066 | 606 | 1.12 (0.85 – 1.47) | 0.42 |

| Total | 6,526 | 1,826 | 1.25 (1.12 – 1.41)* | <0.001 |

Standard deviation = 1.1 mmHg × 10-3

Association statistically significant (p<0.05).

Adjusted for age tertile, gender, race, body mass index, heart rate, LDL cholesterol, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, family history of heart attack, cholesterol lowering medications, transformed C-reactive protein, log transformed CAC+1, and carotid IMT when not first stratifying by these variables.

Adjusted for age tertile, gender, race, body mass index, heart rate, diabetes, family history of heart attack, cholesterol-lowering medications, transformed C-reactive protein, log transformed CAC+1, and carotid IMT

Correlation between DC and Regional Calcification

Table 4 displays a stratified Spearman correlation matrix between DC, TAC, and CAC. All individual correlation coefficients were statistically significant at p<0.001. In general, the correlation between DC and calcification was least strong among men and African-Americans. There was a tighter correlation between DC and TAC than between DC and CAC (ρ=0.315 vs. 0.221, p<0.001 for comparison of coefficients across the entire study population). This difference remained statistically significant in both genders (females p<0.001, males p=0.01) and all races (whites p<0.001, Chinese p=0.03, African Americans p=0.03, Hispanics p=0.008).

Table 4. Correlation between distensibility coefficient, coronary artery calcium, and thoracic aorta calcium.

| Correlation Coefficients [ρ] between: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | ρ DC, TAC | ρ DC, CAC | ρ TAC, CAC |

| Females | -0.349 | -0.271 | 0.487 |

| Males | -0.275 | -0.214 | 0.441 |

| Whites | -0.374 | -0.279 | 0.450 |

| Chinese | -0.361 | -0.261 | 0.441 |

| African Americans | -0.243 | -0.172 | 0.387 |

| Hispanics | -0.358 | -0.269 | 0.454 |

Coronary Artery Calcium (CAC) and Thoracic Aorta Calcium (TAC) defined as continuous variables by the equation: natural log (calcification score + 1).

All individual correlations significant at p<0.001

p<0.001 for ρ DC, TAC vs. ρ DC, CAC for the entire population (ρ=-0.315 vs. -0.221).

Difference remains significant across both genders (p<0.01) and all races: whites (p<0.001), Chinese (p=0.03), African Americans (p=0.03), and Hispanics (p=0.008).

Supplementary Analysis

To facilitate comparison with existing literature, we subsequently conducted exploratory analyses using Young's Modulus (YM), a measure of arterial elasticity, as well as a parameter indicating ‘distension’ achieved by adjusting our primary analysis for pulse pressure. Results were similar to those seen with the analysis using DC. For YM quartile 4 (most elastic), there was a statistically significant 35% increase in TAC prevalence (95% CI 1.02 – 1.80). After adjusting for pulse pressure, there remained a strong association between carotid ‘distention’ and TAC. Point estimates of the association were slightly attenuated, but remained statistically significant (S1-2, please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org).

Discussion

In this large multi-ethnic cohort, we demonstrate a strong association between decreasing carotid distensibility (increasing carotid stiffness) and increasing prevalence of TAC as well as a graded increase in TAC score. This association is independent of age, gender, race, and traditional and emerging cardiovascular risk factors, and importantly remains broadly applicable to low and intermediate Framingham risk groups. In addition, we demonstrate regional variability in the association with calcific atherosclerosis, with carotid DC more highly correlated with TAC than CAC.

Distensibility Coefficient

We chose the distensibility coefficient (DC) as a measure of stiffness because of its intuitive calculation, its common use in the epidemiologic literature27, and its use in the Rotterdam studies enabling direct comparison of results18, 20. Pre-specified analysis with a single index also avoids problems with ‘multiple looks’ seen in studies that test every index of stiffness. We did subsequently conduct an exploratory analysis using Young's Modulus, a measure of arterial elasticity, which revealed similar associations although less strong point estimates of risk (please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org). This pattern is consistent with prior studies relating these two indices11.

Indices such as DC that rely on blood pressure have been criticized due to their reliance on pulse pressure, which is itself an independent predictor of cardiovascular risk28. To adjust for the influence of pulse pressure, we repeated our analyses adjusting for this variable, resulting in attenuated but continued statistically significant associations (see Appendix). After adjustments for pulse pressure, the stiffness parameter becomes more similar to a measure of carotid ‘distention’20.

While inversely correlated (ρ=-0.25), our study demonstrates that DC provides information that is independent of carotid IMT (see Table 2, Model 3). This is consistent with prior studies18, 20. Both DC and carotid IMT can be calculated from the same longitudinal scanning sequence using high resolution ultrasound. This raises the possibility of combining these non-invasive measures for a more comprehensive evaluation of vascular disease29.

Carotid Distensibility and Arterial Calcification

Why is DC more highly correlated with TAC than CAC? There is increasing evidence that the determinants of calcification and atherosclerosis are different for different vascular beds30. For example, studies by Nasir et al. within MESA have shown that while whites have more CAC than Chinese, their burden of TAC is similar31. Gender associations are reversed – while men have more CAC than women, women appear to have more TAC than me31. This observation has been corroborated by Post et al with data from the Pennsylvania Amish, showing that male gender is associated with CAC and not TAC32. In the Amish population, aging is more highly associated with TAC. CAC and TAC are in fact loosely correlated before the age of 50 (ρ=0.135).

There are likely distinct features characterizing the pathophysiology of calcification within the thoracic aorta versus the coronary arteries. Histologic studies demonstrate that calcification of the coronary arteries is largely confined to the intimal layer. However, within the large arteries including the aorta calcification can be present both in the intima and tunica media33. Medial calcification is more strongly associated with aging, diabetes, and severe renal disease34. Structural features of different vascular beds likely also play a role. The elastic carotid artery can be considered structurally more similar to central arteries (such as the aorta35) than the non-elastic predominantly conduit coronary arteries, perhaps contributing to the tighter correlation.

While CAC is a well-established predictor of cardiovascular events36, TAC has been less thoroughly studied with regard to cardiovascular outcomes. Thoracic aortic calcification measured by plain radiography and transesophogeal echocardiography has a well established correlation with obstructive coronary disease37, 38. TAC measured by CT is highly correlated CAC and predicts incidence and progression of CAC39. Amongst patients with stable angina pectoris, TAC is an independent predictor of adverse cardiovascular events40. However, among 2,304 asymptomatic self-referred adults, TAC failed to predict events beyond the Framingham Risk Score and beyond CAC41. A total of 31% of patients (724 total patients) had measurable TAC in this study, likely limiting its discriminatory power. It has not been explored whether TAC predicts adverse aortic outcomes, such as aortic aneurysm, dissection, or rupture, although aortic atherosclerosis is closely associated with ischemic stroke42.

Limitations

Before clinical utility of this application of carotid ultrasound can be established, the chicken-and-egg question remains paramount – does carotid stiffness precede the development of aortic calcification, or is calcinosis a generalized phenomenon that alters the elastic properties of the artery wall? The first major limitation of this study is its cross-sectional nature. While we are able to describe the association of carotid stiffness with calcific atherosclerosis, we are unable to establish temporal relationship. The utility of measures of carotid stiffness would be augmented if early vascular disease was identified, in anticipation of the development of measurable calcification and atherosclerosis. We have planned follow-up studies within MESA to help address this question.

The second major limitation is the use of brachial pulse pressure, rather than a direct measurement of carotid pulse pressure. Peripheral arteries, such as the brachial artery, have pressure wave reflection sites that are closer than for central arteries. Reflected waves travel faster on peripheral arteries, which are stiffer, than on the elastic central arteries, which in asymptomatic patients are more elastic. Due to this ‘amplification phenomenon’, the pulse pressure in the brachial artery will be higher than in the carotid artery, which may lead to systematic underestimation of true carotid distensibility43. MESA participants did not undergo carotid applanation tonometry, which would be required for direct measurement of local carotid pressure. However, it has been suggested that use of brachial blood pressure would in fact lead to systematic underestimation of the association between stiffness and adverse events44.

Perspectives

The results of this study suggest that non-invasive ultrasound measures of carotid artery stiffness demonstrate a “dose-response” association with calcification of the thoracic aorta. The independence of this relationship from carotid IMT, in addition to the greater association with TAC compared to CAC, raises important mechanistic questions and highlights the complexity of the interplay between stiffening, calcinosis, and atherosclerosis. In the future, a combination of these measurements may provide the most comprehensive evaluation of subclinical vascular disease. To evaluate the prognostic significance of these relationships, we have planned longitudinal studies within MESA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org

Source of Funding: This research was supported by R01 HL071739 and contracts N01-HC-95159 through N01-HC-95165 and N01‐HC‐95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Abbreviations List

- DC

distensibility coefficient

- TAC

thoracic aorta calcification

- CT

computed tomography

- IMT

intima-media thickness

- CRP

C-reactive protein

Footnotes

Disclosures: Michael J. Blaha – NONE

Matthew J. Budoff - Speakers' Bureau for General Electric

Juan J. Rivera – NONE

Ronit Katz – NONE

Daniel H. O'Leary – NONE

Joseph F. Polak – NONE

Junichiro Takasu – NONE

Roger S. Blumenthal – NONE

Khurram Nasir - NONE

References

- 1.O'Rourke MF. Principles and definitions of arterial stiffness, wave reflections, and pulse pressure amplification. In: Safar ME, O'Rourke MD, editors. Handbook of Hypertension: Arterial Stiffness in Hypertension. Oxford: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zieman SJ, Melenovsky V, Kass DA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and therapy of arterial stiffness. Arteriocler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:932–943. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000160548.78317.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avolio AP, Chen SG, Wang RP, Zhang CL, Li MF, O'Rourke MF. Effects of aging on changing arterial compliance and left ventricular load in a northern Chinese urban community. Circulation. 1983;68:50–58. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.68.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kupari M, Hekali P, Keto P, Poutanen VP, Tikkanen MJ, Standerstkjold-Nordenstam CG. Relation of aortic stiffness to factors modifying the risk of atherosclerosis in healthy people. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:386–394. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.3.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urbina EM, Srinivasan SR, Kieltyka RL, Tang R, Bond MG, Chen W, Berenson GS. Correlates of carotid artery stiffness in young adults: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Atherosclerosis. 2004;176:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asmar R, Benetos A, Topouchian J, Laurent P, Pannier B, Brisac AM, Target R, Levy BI. Assessment of arterial distensibility by automatic pulse wave velocity measurement: validation and clinical application studies. Hypertension. 1995;26:485–490. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weber T, Auer J, O'Rourke MF, Kvas E, Lassnig E, Berent R, Eber B. Arterial stiffness, wave reflections, and the risk of coronary disease. Circulation. 2004;109:184–189. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000105767.94169.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLeod AL, Uren NG, Wilkinson IB, Webb DJ, Maxwell SR, Northridge DB, Newby DE. Non-invasive measures of pulse wave velocity correlate with coronary arterial plaque load in humans. J Hypertens. 2004;22:363–368. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200402000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Popele NM, Mattace-Raso FU, Vliegenthart R, Grobbee DE, Asmar R, van der Kuip DA, Hofman A, de Feijter PJ, Oudkerk M, Witteman JC. Aortic stiffness is associated with atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries in older adults: the Rotterdam Study. J Hypertens. 2006;24:2371–2376. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000251896.62873.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Redfield MM, Jacobsen SJ, Borlaug BA, Rodeheffer RJ, Kass DA. Age and gender-related ventricular-vascular stiffening: a community based study. Circulation. 2005;112:2254–2262. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.541078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandes VR, Polak JF, Cheng S, Rosen BD, Carvalho B, Nasir K, McClelland R, Hundley G, Pearson G, O'Leary DH, Bluemke DA, Lima JA. Arterial stiffness is associated with regional ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Aterioscler Throm Vasc Biol. 2008;28:194–201. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.156950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laurent S, Katsahian S, Fassot C, Tropeano AI, Gautier I, Laloux B, Boutouyrie P. Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of fatal stroke in essential hypertension. Stroke. 2003;34:1203–1206. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000065428.03209.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blacher J, Geurin AP, Pannier B, Marchais SJ, Safar ME, London GM. Impact of aortic stiffness on survival in end-stage renal disease. Circulation. 1999;99:2434–2439. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.18.2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laurent S, Boutouyrie P, Asmar R, Gautier I, Laloux B, Guize L, Ducimetiere P, Benetos A. Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2001;37:1236–1241. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.5.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sutton-Tyrrell K, Najjar SS, Boudreau RM, Venkitachalam L, Kupelian V, Simonsick EM, Havlik R, Lakatta EG, Spurgeon H, Kritchevsky S, Pahor M, Bauer D, Newman A Health ABC Study. Elevated aortic pulse wave velocity, a marker of arterial stiffness, predicts cardiovascular events in well-functioning older adults. Circulation. 2005;111:3384–3390. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.483628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crouse JR, Goldbourt U, Evans G, Pinsky J, Sharrett AR, Sorlie P, Riley W, Heiss G. Arterial enlargement in the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) cohort. In vivo quantification of carotid arterial enlargement. The ARIC investigators. Stroke. 1994;25:1354–1359. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.7.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Rourke MF, Staessen JA, Vlachopoulus C, Duprez D, Plante GE. Clinical applications of arterial stiffness; defintions and reference values. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15:426–444. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(01)02319-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattace-Raso FU, van der Cammen TJ, Hofman A, van Popele NM, Bos ML, Schalekamp MA, Asmar R, Reneman RS, Hoeks AP, Breteler MM, Witteman JC. Arterial stiffness and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke: the Rotterdam Study. Circulation. 2006;113:657–663. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.555235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leone N, Ducimetière P, Gariépy J, Courbon D, Tzourio C, Dartigues JF, Ritchie K, Alpérovitch A, Amouyel P, Safar ME, Zureik M. Distension of the carotid artery and risk of coronary events: the Three-City Study. Aterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1392–1397. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.164582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Popele NM, Grobbee DE, Bots ML, Asmar R, Topouchian J, Reneman RS, Hoeks AP, van der Kuip DA, Hofman A, Witteman JC. Association between arterial stiffness and atherosclerosis: the Rotterdam Study. Stroke. 2001;32:454–460. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.2.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allison MA, Criqui MH, Wright CM. Patterns and risk factors for systemic calcified atherosclerosis. Aterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:331–336. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000110786.02097.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, Greenland P, Jacob DR, Jr, Kronmal R, Liu K, Nelson JC, O'Leary D, Saad MF, Shea S, Szklo M, Tracy RP. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: Objectives and Design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gamble G, Zorn J, Sanders G, MacMahon S, Sharpe N. Estimation of arterial stiffness, compliance, and distensibility from M-mode ultrasound measurements of the common carotid artery. Stroke. 1994;25:11–16. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carr JJ, Nelson JC, Wong ND, McNitt-Gray M, Arad Y, Jacobs DR, Jr, Sidney S, Bild DE, Williams OD, Detrano RC. Calcified coronary artery plaque measurement with cardiac CT in population based studies: standardized protocol of multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) and coronary artery disease risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. Radiology. 2005;234:35–43. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341040439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Budoff MJ, Katz R, Wong ND, Nasir K, Mao SS, Takasu J, Kronmal R, Detrano RC, Shavelle DM, Blumenthal RS, O'brien KD, Carr JJ. Effect of scanner type on the reproducibility of extracoronary measures of calcification: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Acad Radiol. 2007;14:1043–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Detrano RC, Anderson M, Nelson J, Wong ND, Carr JJ, McNitt-Gray M, Bild DE. Coronary calcium measurement: effect of CT scanner type and calcium measure on the rescan reproducibility-MESA study. Radiology. 2005;236:477–484. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2362040513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lind L, Fors N, Hall J, Marttala K, Stenborg A. A comparison of three different methods to determine arterial compliance in the elderly: the Prospective Investigation of the Vasculature in Uppsala Seniors (PIVUS) study. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1075–1082. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000226197.67052.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laurent S, Cockcroft J, Van Bortel L, Boutouyrie P, Giannattasio C, Hayoz D, Pannier B, Vlachopoulos C, Wilkinson I, Struijker-Boudier H European Network for Non-invasive Investigation of Large Arteries. Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2588–2605. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harloff A, Strecker C, Reinhard M, Kollum M, Handke M, Olschewski M, Weiller C, Hetzel A. Combined measurement of carotid stiffness and intima-media thickness improves prediction of complex aortic plaques in patients with ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:2708–2712. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000244763.19013.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laurent S, Boutouyrie P, Lacolley P. Structural and genetic bases of arterial stiffness. Hypertension. 2005;45:1050–1055. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000164580.39991.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nasir K, Katz R, Takasu J, Shavelle DM, Detrano R, Lima JA, Blumenthal RS, O'Brien K, Budoff MJ. Ethnic differences between extra-coronary measures on cardiac computed tomography: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Atherosclerosis. 2008;198:104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Post W, Bielak LF, Ryan KA, Cheng YC, Shen H, Rumberger JA, Sheedy PF, 2nd, Shuldiner AR, Peyser PA, Mitchell BD. Determinants of coronary artery and aortic calcification in the old order Amish. Circulation. 2007;115:717–724. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.637512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doherty TM, Fitzpatrick LA, Inoue D, Qiao JH, Fishbein MC, Detrano RC, Shah PK, Rajavashisth TB. Molecular, endocrine, and genetic mechanisms of arterial calcification. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:629–672. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iribarren C, Sidney S, Sternfeld V, Browner WS. Calcification of the aortic arch: risk factors and association with coronary disease, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease. JAMA. 2000;283:2810–2815. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.21.2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lehmann ED. Elastic properties of the aorta. Lancet. 1993;342:1417. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92772-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, Bild DE, Burke G, Folsom AR, Liu K, Shea S, Szklo M, Bluemke DA, O'Leary DH, Tracy R, Watson K, Wong ND, Kronmal RA. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1336–1345. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Witteman JC, Kannel WB, Wolf PA, Grobbee DE, Hofman A, D'Agostino RB, Cobb JC. Aortic calcified plaques and cardiovascular disease (the Framingham Study) Am J Cardiol. 1990;66:1060–1064. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90505-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frogoudaki A, Barbetseas J, Aggeli C, Panagiotakos D, Lambrou S, Pitsavos C, Stefanadis C. Thoracic aorta atherosclerosis burden index predicts coronary artery disease in patients undergoing transesophageal echocardiography. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197:232–236. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rivera JJ, Nasir K, Katz R, Takasu J, Allison M, Wong ND, Barr RG, Carr JJ, Blumenthal RS, Budoff MJ. Relationship of thoracic aortic calcium to coronary calcium and its progression (from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis [MESA]) Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:1562–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eisen A, Tenenbaum A, Koren-Morag N, Tanne D, Shemesh J, Imazio M, Fisman EZ, Motro M, Schwammenthal E, Adler Y. Calcification of the thoracic aorta as detected by spiral computed tomography among stable angina pectoris patients: association with cardiovascular events and death. Circulation. 2008;118:1328–1334. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.712141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong ND, Gransar H, Shaw L, Polk D, Moon JH, Miranda-Peats R, Hayes SW, Thomson LE, Rozanski A, Friedman JD, Berman DS. Thoracic aortic calcium versus coronary artery calcium for the prediction of coronary heart disease and cardiovascular disease events. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iribarren C, Sidney S, Sternfeld B, Browner WS. Calcification of the aortic arch: risk factors and association with coronary heart disease, stroke and peripheral vascular disease. JAMA. 2000;283:2810–2815. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.21.2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilkinson IB, Franklin SS, Hall IR, Tyrrell S, Cockcroft JR. Pressure amplification explains why pulse pressure is unrelated to risk in young subjects. Hypertension. 2001;38:1461–66. doi: 10.1161/hy1201.097723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dirk JM, Algra A, van der Graaf Y, Grobbee DE, Bots ML. Carotid stiffness and the risk of new vascular events in patients with manifest cardiovascular disease. The SMART study. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1213–1220. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.