Abstract

Superoxide plays crucial roles in normal physiology and disease; however, its measurement remains challenging because of the limited sensitivity and/or specificity of prior detection methods. We demonstrate that a tetrathiatriarylmethyl (TAM) radical with a single aromatic hydrogen (CT02-H) can serve as a highly sensitive and specific probe. CT02-H is an analogue of the fully substituted TAM radical CT-03 (Finland trityl) with an electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) doublet signal due to its aromatic hydrogen. Owing to the neutral nature and negligible steric hindrance of the hydrogen, preferentially reacts with CT02-H at this site with production of the diamagnetic quinone methide via oxidative dehydrogenation. Upon reaction with , CT02-H loses its EPR signal and this EPR signal decay can be used to quantitatively measure . This is accompanied by a change in color from green to purple, with the quinone methide product exhibiting a unique UV–Vis absorbance (ε =15,900 M−1 cm−1) at 540 nm, providing an additional detection method. More than five-fold higher reactivity of CT02-H for relative to CT-03 was demonstrated, with a second-order rate constant of 1.7 × 104 M−1 s−1 compared to 3.1 × 103 M−1 s−1 for CT-03. CT02-H exhibited high specificity for as evidenced by its inertness to other oxidoreductants. The generation rates detected by CT02-H from xanthine/xanthine oxidase were consistent with those measured by cytochrome c reduction but detection sensitivity was 10- to 100-fold higher. EPR detection of CT02-H enabled measurement of very low flux with a detection limit of 0.34 nM/min over 120 min. HPLC in tandem with electrochemical detection was used to quantitatively detect the stable quinone methide product and is a highly sensitive and specific method for measurement of , with a sensitivity limit of ~2 × 10−13 mol (10 nM with 20-μl injection volume). Based on the O2-dependent linewidth broadening of its EPR spectrum, CT02-H also enables simultaneous measurement of O2 concentration and generation and was shown to provide sensitive detection of extracellular generation in endothelial cells stimulated either by menadione or with anoxia/reoxygenation. Thus, CT02-H is a unique probe that provides very high sensitivity and specificity for measurement of by either EPR or HPLC methods.

Keywords: Oxygen free radicals, Reactive oxygen species, Electron paramagnetic resonance, spectroscopy, Spin trapping, Trityl radical, Free radicals

Introduction

In view of the critical roles of superoxide in both normal cellular signaling and disease [1–6], as well as the limitations of prior detection methods, there is a great need for development of specific high-sensitivity methods for its measurement in biomedical systems. Superoxide is a one-electron reduction product of molecular oxygen (O2) that is mainly generated from the mitochondrial electron transfer chain [7–10] and through several enzyme-mediated processes [11,12]. It has been estimated that 1–2% of O2 is converted into in isolated mitochondria [13]. As a critical reactive oxygen species (ROS), not only takes part in host defense in phagocytic cells, but also is involved in signal transduction and regulation in many types of cells [6]. On the other hand, oxidative stress induced by and other ROS is also associated with pathogenesis of many important diseases including cancer, arteriosclerosis, heart attack, stroke, diabetic vascular disease, and a variety of inflammatory diseases [3,6]. Thus, sensitive and selective detection of in in vitro and in vivo systems is of paramount importance to understand its roles in normal physiology and disease.

Over the past decades, several techniques have been developed for the measurement of , including ferricytochrome c reduction [14], electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR)–spin trapping [15], electrochemistry [16], and fluorescence and chemiluminescence [17,18], but most of these techniques are limited by low sensitivity and/or specificity. Efforts have been made to improve these techniques. For example, new spin traps with enhanced stability of the corresponding spin adducts have been developed [19,20]. In addition, the new HPLC–fluorescence tandem technique was also utilized to compensate for the low specificity of fluorescent detection [21]. Despite these innovations, the identification and quantitation of the low biological fluxes of formation remain challenging.

In recent years a tetrathiatriarylmethyl (TAM) radical (OX063; Scheme 1) has been proposed as an ideal spin probe for in vivo EPR spectroscopy and imaging suitable for the measurement of O2 concentrations based on the O2-dependent linewidth broadening of its EPR spectrum [22,23]. It was also proposed to serve as a highly selective and sensitive probe [24,25]. Superoxide was conveniently measured by following the changes in the EPR signal intensity or UV–Vis absorbance of OX063. Recently, the reaction mechanism of the TAM radicals OX063 and CT-03 with was characterized [26] and the corresponding quinone methide products were identified [26,27]. Owing to unique EPR properties and high biostability [28], TAM radicals have been so far the most promising paramagnetic probes for EPR spectroscopy/imaging applications and have been utilized to measure extracellular [29] and intracellular [30,31] O2 levels, generation [24], pH [32–35], and glutathione levels [36], as well as to assess total redox status [37,38]. Thus, combined with recent progress in low-frequency EPR instrumentation, TAM radicals have great potential for measurement and mapping of in tissues.

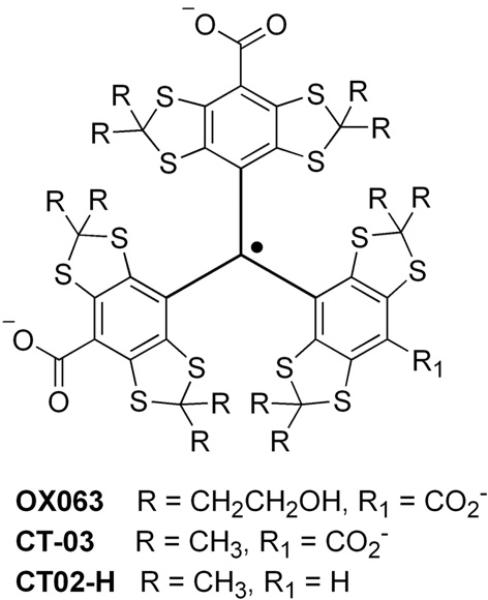

Scheme 1.

Molecular structure of TAM radicals.

In this article, we report a partially substituted TAM radical, CT02-H (Scheme 1), as a new probe with a high rate constant providing enhanced sensitivity. Using xanthine/xanthine oxidase as a source, the reactivity of CT02-H with was compared with that of the fully substituted TAM radical CT-03, and the reaction rate constants of both TAM radicals with were determined using self-dismutation as the competition reaction. The reaction mechanism with was determined based on product analysis. Applications of CT02-H for detection and quantitation of high or low fluxes by EPR spectroscopy or HPLC/ electrochemistry techniques were performed. Cellular generation of in endothelial cells was also measured. CT02-H was found to provide excellent sensitivity and specificity for detection and also to enable simultaneous measurement of O2 concentrations.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Xanthine (X), xanthine oxidase (XO), glutathione (GSH), ascorbic acid (Asc), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), ammonium iron(II) sulfate hexahydrate ((NH4)2Fe(SO4)2•6H2O), diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA), nitrilotriacetic acid disodium salt (NTA), catalase, cytochrome c, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) from bovine erythrocytes were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. TAM radicals CT-03 and CT02-H were synthesized as previously described [30,32,39]. 5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) was purchased from Dojindo Molecular Technologies and 5-(diethoxyphosphoryl)-5-methyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DEPMPO) from Enzo Life Science. The concentration of CT02-H was determined by EPR using the purified CT-03 as standard. Stock solutions (1 mM) of CT-03 and CT02-H as carboxylate sodium forms were prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stored at −20 °C. All other chemicals were commercially available unless otherwise indicated.

EPR spectroscopy

All EPR spectra were recorded at room temperature using a Bruker X-band EPR spectrometer. Samples were loaded into EPR capillary tubes. The following acquisition parameters were used: microwave power, 0.2–10 mW for TAM radicals and 20 mW for the spin trapping with nitrones; modulation frequency, 30–100 kHz; time constant, 21 ms; modulation amplitude, 0.03–1 G.

Stability studies in the presence of biological oxidoreductants

Aqueous solutions of GSH (1 mM), Asc (1 mM), and H2O2 (1 mM) were used. The Fe(II)–NTA complex was prepared by dissolving (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2 and NTA at a molar ratio of 1:2 in water under anaerobic conditions. The Fe(III)–NTA solution (Fe:NTA 1:2) was prepared by slow addition of the appropriate volume of acidic Fe(III) stock solution into a vigorously stirred solution of NTA in water. The resulting solution was slowly neutralized to pH 7.4 using 0.1 M NaOH. Either Fe(II)–NTA or Fe(III)–NTA solution was freshly prepared before use. Hydroxyl radical (HO•) was continuously generated from the system consisting of Fe(III)–NTA (0.1 mM) and H2O2 (1 mM). Spin trapping EPR experiments with the spin trap DMPO were carried out to verify the production of HO•. Superoxide was generated using the X/XO system using XO (10 mU/ml) and X (100 μM) in the presence of DTPA (0.1 mM). Alkylperoxyl radical was generated by thermolysis of 2,2′-azobis-2-methylpropanimidamide, dihydrochloride (AAPH; 1 mM) at 37 °C in the presence or absence of SOD (200 U/ml). Peroxynitrite (ONOO–) was generated by decomposition of SIN-1 (1 mM) at 37 °C in the presence or absence of SOD (50 U/ml). EPR spectra were recorded 30 min after mixing the TAM radical solution (20 mM) with various oxidoreductants in PBS. The effects of various reactive species on CT02-H were expressed as the percentage of CT02-H remaining after exposure to the reactive species for 30 min, which was obtained by comparing the double integral of the EPR signal in each system with that of CT02-H (20 μM). Each experiment was conducted three times.

Cyclic voltammetry

Cyclic voltammetry was performed on a potentiostat and computer-controlled electroanalytical system. Electrochemical measurements were carried out in a 10-ml cell equipped with a glassy carbon working electrode (7.07 mm2), a platinum-wire auxiliary electrode, and a Ag/AgCl reference electrode. Solutions of TAM radicals (1 mM) were degassed by bubbling with nitrogen gas before the detection. The redox potentials were calculated according to the relation .

Kinetic studies

The apparent second-order rate constants of TAM radicals (CT02-H and CT-03) with were determined using the self-dismutation as a competition reaction at pH 7.4. XO (10 mU/ml) was added to the solutions containing various concentrations of TAM radical, X (100 μM), and DTPA (0.1 mM) in PBS (pH 7.4). Incremental EPR spectra were recorded 30 s after mixing. The initial rate of the CT02-H decay was determined within 30–80 s, during which the earliest linear curve becomes evident. Data were plotted using Eq. (1),

| (1) |

where V is the initial rate of the TAM radical decay, k and kdis are the second-order rate constant of the TAM radical with and the self-dismutation rate at pH 7.4 (2.4 × 105 M−1 s−1) [40,41], respectively, and F is the generation rate in the X/XO system, which was determined to be 0.115 μM/s by ferricytochrome c kinetic competition (see Supplementary Fig. S6). The apparent second-order rate constants of CT02-H and CT-03 with were determined to be 1.7 × 104 and 3.1 × 103 M−1 s−1, respectively.

Oxygen sensitivity

The O2 sensitivity of CT02-H was evaluated as previously described [34,36–38]. Briefly, a solution of CT02-H (20 μM) in PBS was transferred into a gas-permeable Teflon tube (i.d. 0.8 mm) and then the tube was sealed at both ends. The sealed sample was placed inside a quartz EPR tube with open ends. Nitrogen or a N2/O2 gas mixture with varying concentrations of O2 was allowed to diffuse into the EPR tube. After 20 min of equilibration, the EPR spectrum was recorded and the peak–peak linewidth was calculated.

Determination of the generation rate of by EPR and UV–Vis spectroscopy

The generation rates at various fluxes from the X/XO system were assessed by EPR spectroscopy using CT02-H with measurement of its signal decay. These results were compared to values measured by UV–Vis spectroscopy using cytochrome c. UV–Vis spectra were recorded at room temperature on a Varian Cary 50 Bio spectrophotometer. First, the enzymatic activity of the commercial XO was determined by monitoring the production of uric acid (12.2 mM−1 cm−1 at 290 nm) in the presence of excess X. Then, various concentrations of XO (0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 mU/ml) were added to the solution containing X (100 μM), DTPA (0.1 mM), and CT02-H (50 μM), with the generation rate determined from the decay rate of the EPR signal of CT02-H. For the measurements of the generation rate from the reduction of ferricytochrome c, various concentrations of XO (2, 5, 10, and 20 mU/ml) were added to solutions containing X (100 μM), EDTA (100 mM), catalase (200 U/ml), and ferricyto-chrome c (100 mM). The generation rate was determined from the reduction of ferricytochrome c to ferrocytochrome c by . It was measured from the slope of the time-dependent production of ferrocytochrome c measured at 550 nm using an extinction coefficient of 2.1 × 104 M−1 cm−1 [42,43].

Preparation of QM1 and 18O-labeled QM1

The quinone methide product QM1 was prepared from CT02-H using the previously reported method [26] with some modification. XO (0.05 U/ml) was added to the solution containing CT02-H (8.6 mg), X (1 mM), and DTPA (0.1 mM) in 100 ml of PBS (pH 7.4). This reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h with a gentle bubbling of O2 gas. Then, a citric acid solution (30 ml, 8%, w/v) was added and QM1 was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 50 ml). The combined organic layers were dried on anhydrous sodium sulfate and concentrated. The resulting residue was redissolved in PBS and purified by RP-flash chromatography over a prepacked C18 column using a gradient from 0/100 to 30/80 of acetonitrile/water mixture to afford 8.5 mg of pure QM1 as a purple solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, acetone-d6) 1.693 (s, 6H), 1.782 (s, 6H), 1.795 (s, 6H), 1.812 (s, 6H), 1.889 (s, 6H), 1.896 (s, 6H); 13CNMR (600 MHz, acetone-d6) 29.5, 30.0, 31.8, 33.3, 33.7, 35.4, 63.4, 64.0, 64.5, 123.7, 130.8, 131.6, 140.4, 141.3, 141.7, 142.8, 146.1, 153.3, 167.6, 173.3; HRMS (electrospray ionization (ESI), negative) calcd for ([M–H]− ), 968.9290; found, 968.9295. A stock solution of QM1 with aconcentration of 3 mM was prepared in PBS (10 mM, pH 7.4) for the subsequent HPLC analysis.

For the preparation of the 18O-labeled QM1, isotopically enriched 18O2 gas (99 atom% 18O; Sigma) was used instead of 16O2. Briefly, the solution containing CT02-H (0.2 mM), X (0.8 mM), and DTPA (0.1 mM) in 3 ml of PBS (pH 7.4) was bubbled with argon for 30 min and then 18O2 for 10 min. Thereafter, XO (0.02 U/ml) was added and the resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 30 min with gentle bubbling of 18O2 gas. Then, the citric acid solution (1 ml, 8%, w/v) was added and the 18O-labeled QM1 was extracted with ethyl acetate. Mass spectrometry (MS) analysis was carried out on the resulting organic solution.

HPLC detection of the product of CT02-H with

The solutions (10 μl) containing various concentrations of QM1 or CT02-H were injected separately into the HPLC system (Coul-Array System from ESA Analytical, Ltd., Chelmsford, MA, USA) on a C18 Tosoh Bioscience ODS-80Tm column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) with refrigerated autosampler and ESA software for data collection and analysis. The mobile phase consisted of 20 mM ammonium acetate:methanol:acetonitrile 40:20:40 (v/v/v), pH 7.0, at a flow rate of 1.2 ml/min, which was filtered and degassed before use. CT02-H and its product with (QM1) were detected at +600 and +800 mV, respectively, using the electrochemical detector of the ESI Coulchem 6210 four-sensor electrochemical cell. The retention time was 4.2 min for the quinone methide QM1 and 9.6 min for CT02-H. The HPLC peak intensity of QM1 linearly increased with the concentration, and the detection limit of this HPLC/electro-chemistry technique was determined to 2 × 10−13 mol of QM1, which was determined from a concentration of 20 nM, with injection volume of 10 μl, or 10 nM with volume of 20 μl.

Detection of generation in cells

Bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs) were grown to confluence in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, glutamine (30 μg/ml), penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), MEM nonessential amino acids (1%), and endothelial cell growth supplement (10 mg/ml) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. Cells were used between passages 7 and 10. After removal of the culture medium, the cells were washed with PBS and treated with trypsin. The suspended cells were centrifuged at 500g for 5 min and washed with PBS. The resulting cell pellet was resuspended in PBS at a concentration of 3.8 × 106 cells/ml. The generation was initiated by adding menadione (100 μM) in the presence of CT02-H (0.2 μM) or DEPMPO (20 mM). Then, the cell sample was transferred to a glass capillary tube and EPR spectra were recorded.

The concentration effect of menadione on the cellular generation was investigated by HPLC. The culture medium was removed from BAECs cultured in a six-well plate. The cells were then washed three times by PBS and incubated with CT02-H (50 μM) and various concentrations of menadione (0, 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 μM) in PBS for 15 min. The medium containing CT02-H and QM1 was taken and centrifuged at 11,000g for 10 min, and the supernatant was analyzed by HPLC. For studies of BAECs subjected to the pathophysiological stimulus of hypoxia and reoxygenation, cells were treated in a Billups Rothenberg chamber purged with 95% nitrogen, 5% CO2 gas for 4 h followed by incubation at 37 °C for 24 h followed by reoxygenation with air.

Simultaneous measurement of generation and O2 consumption

XO (10 mU/ml) was added to a solution containing CT02-H (100 μM), X (100 μM), DTPA (0.1 mM) in PBS (pH 7.4). The lowfield peak of CT02-H was monitored for 35 min. The concentration of CT02-H at each time point was obtained by comparing the double integral of its EPR spectrum with that of a 100 μM CT02-H standard sample, and the linewidth of the probe at each time point was used to calculate O2 concentration according to the O2 sensitivity of CT02-H as mentioned above. Therefore, the initial generation rate (4.9 μM/min) and O2 consumption rate (20.7 μM/min) could be obtained in this single measurement. Based on these data, the efficiency of generation from O2 in the X/XO system was determined to be 24%, consistent with the previously reported values (20–30%) [42,44,45].

Results

Fig. 1 shows the typical EPR spectrum of CT02-H under aerobic conditions, which exhibits a doublet with a hyperfine splitting of 2.35 G at pH 7.4 due to the interaction of the unpaired spin with the proton on the partially substituted aromatic group. The magnitude of this hyperfine splitting is pH-dependent, which was previously proposed to enable pH measurement [32]. In addition to the doublet small satellite lines are seen due to natural abundance 13C splittings.

Fig. 1.

EPR spectrum of CT02-H in PBS.

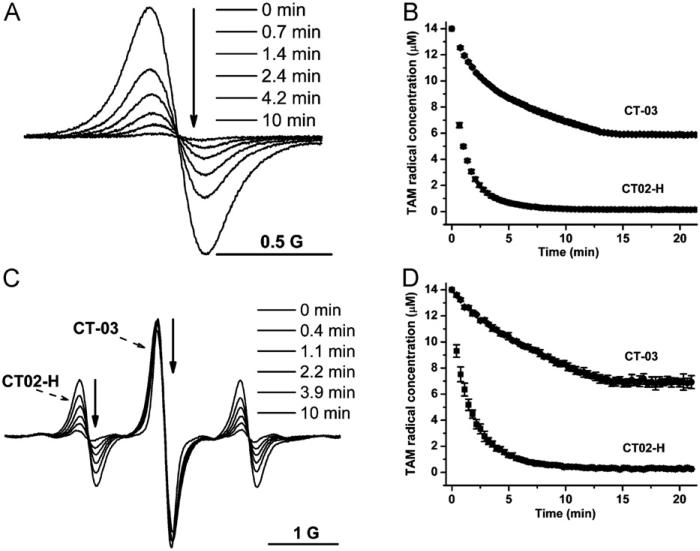

To check if CT02-H can function as a detection probe, its reactivity with was investigated. The X/XO system was used as a source. As shown in Fig. 2A, induced the rapid decay of the signal intensity of CT02-H, as detected from the low-field peak, and the signal almost completely disappeared in 10 min. In contrast, the reaction of the fully substituted TAM radical CT-03 with is much slower. The EPR signal of CT-03 gradually decayed over time, with ~45% of the signal remaining after 15 min, and no further reaction was observed after that time, possibly because xanthine and/or O2 in the system was completely depleted (Fig. 2B). A much higher reactivity of CT02-H to than of CT-03 was further verified by simultaneous measurement of the signal intensity decays of both TAM radicals induced by (Fig. 2C). Whereas CT02-H was quickly quenched by , CT-03 was relatively stable. Of note, only minimal change in the EPR signal intensity was observed for CT-03 in Fig. 2C because of the decrease in the O2 concentration in the system, which narrows its EPR signal and offsets the signal intensity decay from the radical quenching. In fact, the concentration of CT-03 obtained from the double integration of the EPR signal did gradually decrease over time (Fig. 2D). The initial decay rates for CT02-H and CT-03 were 5.7 and 1.0 μM/min, respectively, and thus the second-order reaction rate constant of CT02-H with was approximately 5.7 times that for CT-03 because the same concentration (14 μM) was used for both radicals.

Fig. 2.

(A) -induced decay of the low-field peak in the EPR signal of CT02-H. XO (0.01 U/ml) was added to the solution containing CT02-H (14 μM), DTPA (100 μM), and X (100 μM) in PBS (pH 7.4) and EPR spectra were recorded over time. (B) Plot of TAM radical concentration as a function of time. Error bars are small and within the symbols. (C) Simultaneous measurement of EPR signal decays in both CT02-H and CT-03 after addition of XO (0.01 U/ml) into the solution containing CT02-H (14 μM), CT-03 (14 μM), DTPA (100 μM), and X (100 μM) in PBS (pH 7.4). (D) Plot of TAM radical concentration as a function of time according to the data in (C). TAM radical concentration was quantitated by comparing the double integral of the EPR signal of each radical with its predetermined concentration (i.e., 14 μM). All the experiments were repeated three times.

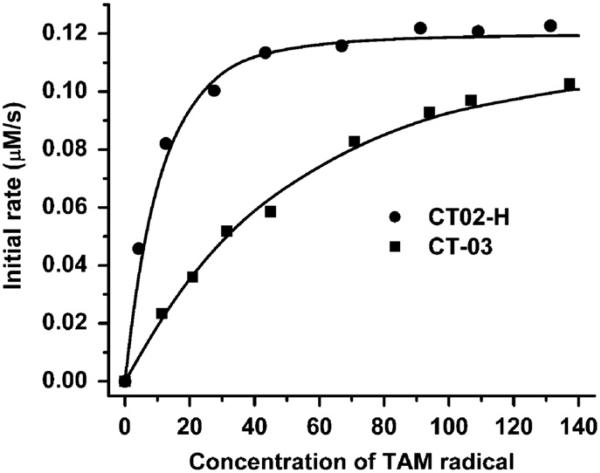

To further quantitate the reactivity of CT02-H with , the apparent second-order rate constants of CT02-H with were determined using self-dismutation as a competition reaction. Fig. 3 shows the concentration effect of CT02-H on its initial decay rates in the presence of (see Supplementary Fig. S7 for the kinetic decay of CT02-H induced by ). The initial decay rate increases with the CT02-H concentration and then reaches a plateau at the concentration of ~45 mM owing to complete trapping of by CT02-H. These data were fitted with Eq. (1) and the apparent second-order rate constant of CT02-H with was calculated to be 1.7 × 104 M−1 s−1 using the self-dismutation rate constant of (2.4 × 105 M−1 s−1) at pH 7.4 [40,41] and the predetermined generation rate (0.115 ± 0.003 μM/s) (see Supplementary Fig. S6). For comparison, a similar kinetics assay was also carried out for CT-03, and its rate constant was determined to be 3.1 × 103 M−1 s−1, which is more than five times lower than that of CT02-H. Because of the relatively low reaction rate with , CT-03 even at 140 μM concentration did not fully outcompete the self-dismutation (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of concentration on the -induced initial decay of CT02-H and CT-03. XO (10 mU/ml) was added to the solution containing DTPA (100 μM), X (100 μM), and various concentrations of CT02-H or CT-03 in PBS (pH 7.4) and EPR spectra were continuously recorded. The initial rate of the decay of CT02-H or CT-03 was determined within 30–80 s.

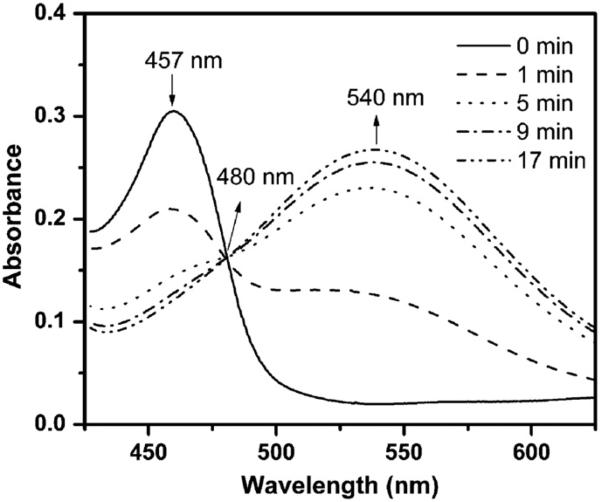

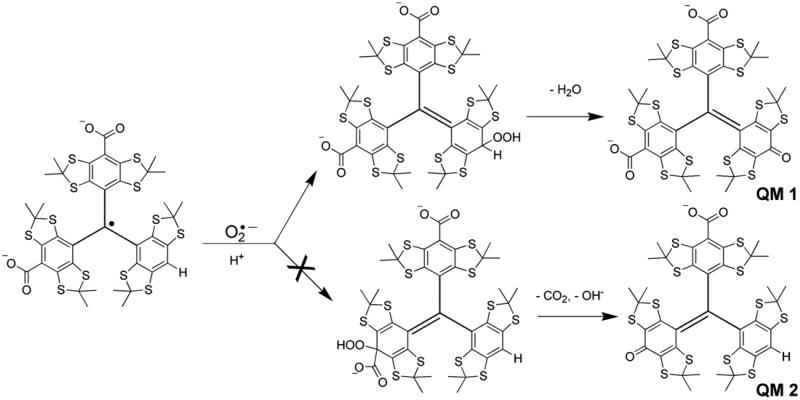

To explore the reaction mechanism of CT02-H with , UV–Vis spectroscopic studies were performed. As shown in Fig. 4, CT02-H has a characteristic peak at 457 nm in the UV–Vis absorption spectrum with an extinction coefficient of 17,900 M−1 cm−1. Compared to CT-03 (467 nm), the maximal absorbance of CT02-H has a blue shift of approximately 10 nm. The reaction between CT02-H and led to the rapid but time-dependent decrease in the absorbance at 457 nm, consistent with the above EPR experimental results. Concurrently, a new absorbance at 540 nm (ε = 15,900 M−1 cm−1) appeared due to the formation of a product that shared an isosbestic point with CT02-H at 480 nm. The presence of the isosbestic point indicates that the reaction of CT02-H with stoichiometrically generates the product, thus enabling quantitation of by measuring the product. According to previous studies regarding the reaction of CT-03 with [26], the product could be the corresponding quinone methide QM1 or QM2 (Fig. 5). Subsequent ESI–MS analysis (negative mode) showed that the product with m/z 968.9295 is QM1 (calculated m/z: 968.9290) instead of QM2 (calculated m/z: 924.9392; see Supplementary Fig. S1). The molecular structure of QM1 was further characterized by 1H and 13C NMR spectra (see Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3), which were well consistent with the previously reported data [46]. To further confirm the origin of the oxygen atom in the quinone QM1, 18O2 instead of 16O2 was used to generate 18O2 in the X/XO system. The resulting product has an 18O inserted in the molecule as determined by the molecular ion of [M+Na]+ in a high-resolution mass spectrum at 994.9276 (calculated value 994.9308, Supplementary Fig. S14), verifying that the oxygen atom in QM1 comes from . Therefore, the reaction of CT02-H with resulted in oxidative dehydrogenation in contrast to the oxidative decarboxylation in the case of CT-03 [26].

Fig. 4.

UV–Vis studies of the reaction of CT02-H with . UV–Vis spectra were continuously recorded after addition of XO (8 mU/ml) into the solution containing CT02-H (16.9 μM), DTPA (100 μM), and X (200 μM) in PBS (pH 7.4).

Fig. 5.

Possible mechanisms of CT02-H reaction with .

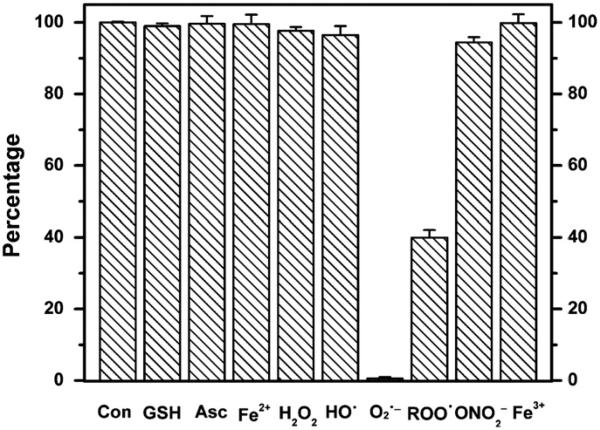

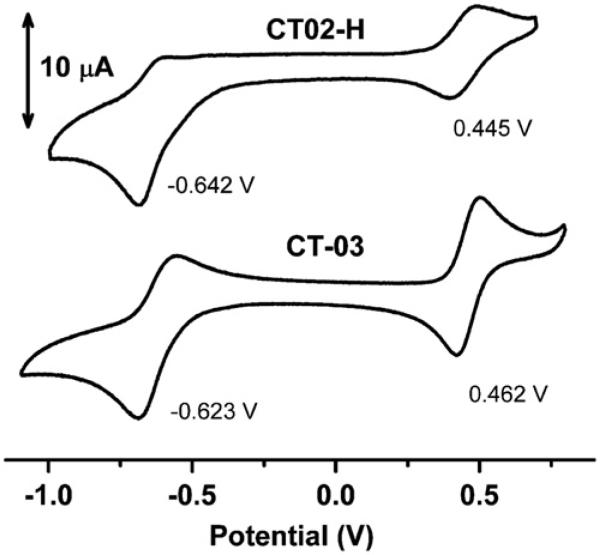

To investigate the specificity of the CT02-H reaction with , its reactivity toward other reactive species was also studied. As shown in Fig. 6, CT02-H was stable toward most reducing agents such as Asc (1 mM), GSH (1 mM), and Fe(II)–NTA (0.1 mM), as well as the oxidants H2O2 (1 mM), Fe(III)–NTA (0.1 mM), HO•, and peroxynitrite generated from decomposition of SIN-1 (1 mM). Although there were only slight changes in the signal intensity after 30-min incubation of CT02-H with the highly reactive HO• and peroxynitrite, reactions between CT02-H and these two species may still exist wherein the paramagnetism of CT02-H is preserved. Reactions of CT02-H with alkyl peroxyl radical generated from the thermolysis of AAPH (1 mM) were observed with ~40% of signal remaining after 30-min incubation. The lack of effect of SOD (200 U/ml) on the decay of CT02-H induced by alkylperoxyl radicals confirmed the moderate reactivity of CT02-H with this species (data not shown). The reaction of CT02-H with alkylperoxyl radicals has the same product (i.e., QM1) as that of the reaction with as verified by UV–Vis spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. S13). Overall, the stability of CT02-H toward various reactive species is very similar to the results observed previously for CT03 and OX063 [24,34]. Cyclic voltammetric studies (Fig. 7) showed that CT02-H, as a neutral radical, can undergo reversible one-electron oxidization to the corresponding TAM cation at E1/2 (ox)=0.445 V vs Ag/AgCl (ΔEp=79 mV) and quasi-reversible one-electron reduction to the corresponding anion E1/2 (red)= −0.642 V vs Ag/AgCl (ΔEp 82 mV). These values are very similar to those observed for CT-03=under the same conditions, i.e., E1/2 (ox)=0.462 V vs Ag/AgCl and E1/2 (red) = −0.623 V vs Ag/AgCl. Similar redox potentials for CT02-H and CT-03 further verified their similar stability toward various oxidoreductants. Although the ester form of CT02-H was previously reported to react with O2 at high concentration [27], no significant signal decay after CT02-H (20 μM) in PBS was observed in room air for 5 h at 37 °C, which supports its use for the measurement of (see Supplementary Fig. S10). Additionally, incubation of CT02-H with the serum protein bovine serum albumin at 37 °C for 5 h resulted in only 4% signal decay (see Supplementary Fig. S10).

Fig. 6.

Effects of various reactive species on CT02-H expressed as a percentage of CT02-H remaining after exposure to reactive species for 30 min. The percentage was obtained by comparing the double integral of the EPR signal in each system with that of CT02-H (20 μM). Each experiment was carried out at least three times. See details under Materials and methods.

Fig. 7.

Cyclic voltammograms of CT02-H (1 mM) and CT-03 (1 mM) in PBS (pH 7.4) containing 0.15 M KCl. Scan rate: 50 mV/s.

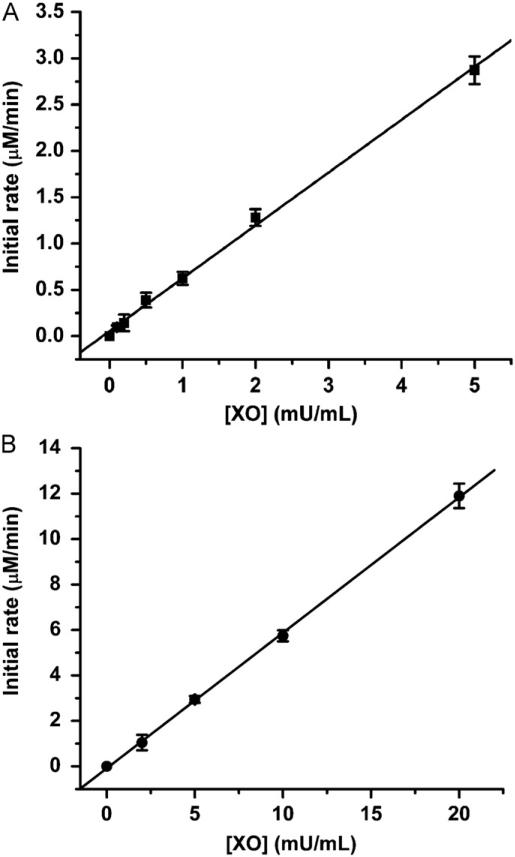

To determine if CT02-H can be used to measure , various fluxes were generated in the presence of a constant concentration of X (100 μM) and various concentrations of XO (0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 mU/ml). As shown in Fig. 8A, CT02-H had a good response to the fluxes, and the initial decay rate of CT02-H was linearly correlated with the XO concentration. The slope (0.56±0.02 μmol/min/U) of the curve obtained by the linear fitting corresponds to the generation activity of XO. Based on this value, the generation activity can be further estimated as 28±1% of the total O2 consumption. Comparatively, the cytochrome c detection technique was also used to determine the generation activity of XO (Fig. 8B). The obtained value (0.58±0.02 μmol/min/U) was consistent with that obtained using CT02-H, implying that CT02-H can be used to quantitate .

Fig. 8.

(A) Detection of various fluxes by EPR using CT02-H. The incubation mixture contained X (100 μM), DTPA (100 μM), CT02-H (50 μM) in PBS (pH 7.4) at room temperature. Various concentrations of XO (0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 mU/ml) were added to initiate the reaction. The decay rate of CT02-H, that is, the generation rate, was determined to be 0.56±0.02 μmol/min/U. (B) Detection of various fluxes by UV–Vis spectroscopy using ferricytochrome c. The incubation mixture contained X (100 μM), cytochrome c (100 μM), EDTA (100 μM), and catalase (200 U/ml) in PBS (pH 7.4) at room temperature. Various concentrations of XO (2, 5, 10, and 20 mU/ml) were added to initiate the reaction. The generation rate was determined to be 0.58±0.02 mmol/min/U. See details under Materials and methods.

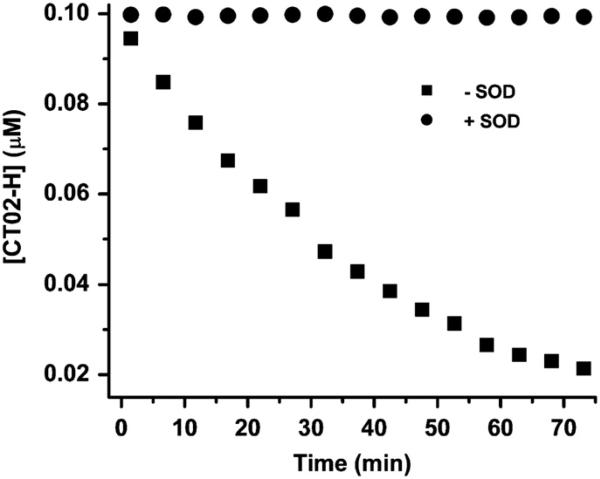

To estimate the detection limit of CT02-H, we monitored the signal decay of CT02-H (0.1 μM) in the presence of low flux generated from the mixture containing X (2 μM), XO (0.05 mU/ml), and DTPA (100 μM). As shown in Fig. 9, CT02-H gradually decayed over time in this system with approximately 25% of CT02-H remaining after 60-min reaction. The incomplete reaction of CT02-H with may result from: (1) less trapped by CT02-H with time due to a significant decrease in the CT02-H concentration or (2) decreased generation possibly due to the consumption of xanthine and O2 as well as to decreased enzyme activity. Addition of Cu/Zn SOD (200 U/ml) completely inhibited the decay of CT02-H, verifying that the CT02-H decay is specific to . However, the EPR spin trapping technique using DEPMPO as a spin trap could not detect any signal under the same condition and required fivefold more XO (i.e., 0.25 mU/ml) to reach a detectable signal (see Supplementary Fig. S4), indicating that the new EPR method using CT02-H as a probe can achieve much higher sensitivity. According to the plot of the generation rate as a function of the XO concentration in Fig. 8, the generation rate is estimated to be 25 nM/min, using 0.05 mU/ml XO and excess X. Assuming that the EPR technique can safely distinguish 5% of the signal intensity change, the present technique can measure a flux of ~1.7 nM/min over 60 min detection.

Fig. 9.

Measurement of the low flux by CT02-H (0.1 μM). The low flux was generated using a low concentration of XO (0.05 mU/ml), X (2 μM), and DTPA (100 μM) in PBS. The concentration of CT02-H was quantitated by comparing the double-integrated EPR signal of each radical with its predetermined concentration (i.e., 0.1 μM).

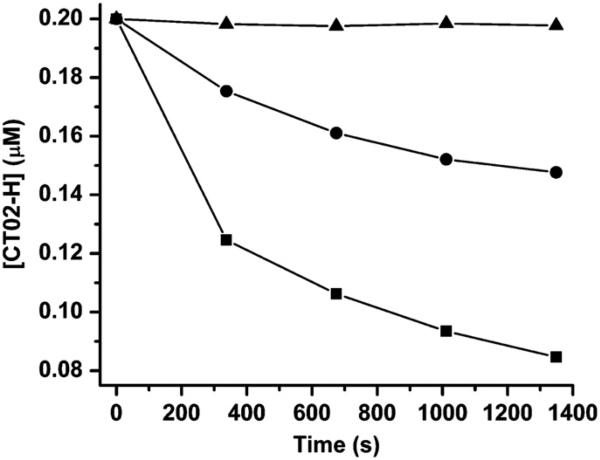

The application of CT02-H for measurement of the generation in cells was also explored. The generation was stimulated in BAECs by adding menadione [47]. As shown in Fig. 10, the generation in cells (3.8 × 105 cells/ml, 40 μl) induced the quick decay of CT02-H with approximately 60% of signal loss after 20-min incubation. The decrease in cell density from 3.8 × 105 to 1.5 × 105 cells/ml (15,000 to 6000 cells) significantly slowed the decay of CT02-H, with slightly more than 25% signal loss after 20-min incubation. Near-complete inhibition of the CT02-H decay by exogenous addition of SOD (200 U/ml) was seen, confirming the specificity of the reaction of CT02-H with in this system. The complete inhibition of the CT02-H decay by the cell-impermeative SOD also implies that CT02-H acts only as an extracellular probe owing to its negatively charged nature. The sensitivity for detection of cellular generation with CT02-H was high and could be detected from as few as 1200 cells over 20 min with a 5% signal decrease. For comparison, a regular spin trapping experiment was also performed using DEPMPO (20 mM) but a much higher cell density of 1.2 × 106 cells/ml, with corresponding cell number of 48,000, was required to reach a detectable EPR signal (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Fig. 10.

Cellular generation of detected by CT02-H. The generation was stimulated by adding menadione (100 μM) to the cell suspension (3.8 × 105 (■) or 1.2 × 105 (●) cells/ml in a 40-μl EPR capillary tube) containing CT02-H (0.2 μM) and DTPA (100 μM) in DMEM. EPR spectra were recorded 5 min after the addition of menadione. SOD (200 U/ml) (△) was used to verify the generation. The concentration of CT02-H was quantitated by comparing the double integral of the EPR signal of each radical with its predetermined concentration (i.e., 0.2 μM).

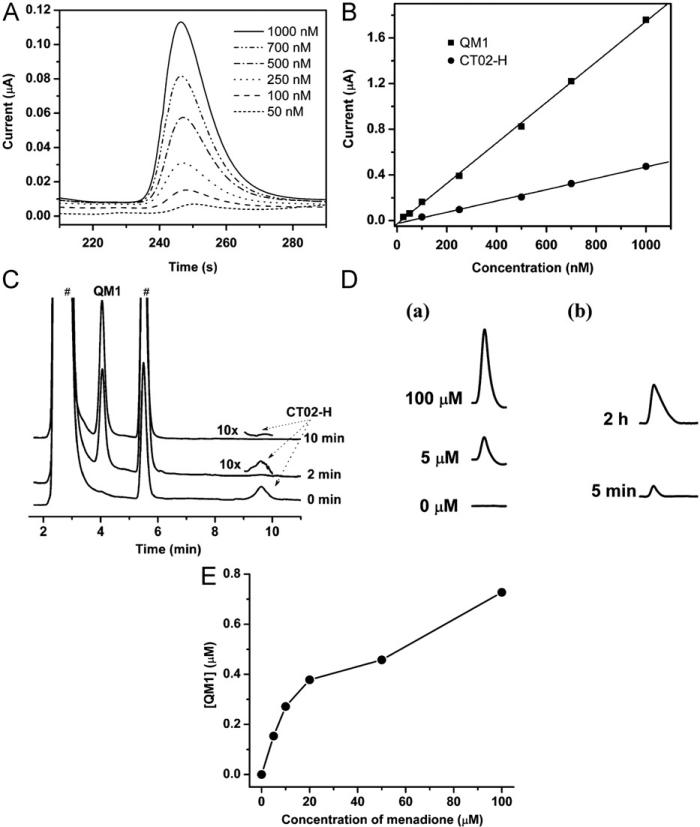

Because the reaction of CT02-H with resulted in the production of the stable QM1 (Supplementary Fig. S12), HPLC in tandem with electrochemical detection was used to detect this specific product. Fig. 11A shows the chromatograms using electro-chemical detection of QM1 at various concentrations with a retention time of ~250 s (~4.2 min). As shown in Fig. 11B, the HPLC peak intensity of QM1 is in good agreement with the amounts of down to 2 × 10−13 mol or 20 nM with an injection volume of 10 μl. With increasing sample volume from 10 to 20 μl the sensitivity could be extended to ~10 nM QM1. Fig. 11C shows the HPLC–EC chromatograms of the reaction of CT02-H with from the X/XO system. Similar to the EPR results in Figs. 2A and 2B, CT02-H with the retention time of 9.6 min was quickly and uniquely transformed into QM1 upon reaction with with a transformation of ~80% after 2 min incubation, and this reaction was complete at 10 min. To further investigate the potential of the HPLC technique for detection, the generation from BAECs stimulated by menadione was also studied by HPLC. As shown in Figs. 11D and 11E, menadione stimulates generation in a concentration-dependent manner, with more generation at higher concentrations of menadione. No EPR signal decay of CT02-H (20 μM) was observed in the presence of menadione (500 μM; data not shown), proving the specificity of CT02-H for . Moreover, reoxygenation of BAECs that underwent anoxia for 24 h immediately induced generation (~0.08 μM), and extended reoxygenation treatment for 2 h further increased the production detected (~0.48 μM; Fig. 11D).

Fig. 11.

(A) HPLC–electrochemistry chromatograms of QM1. (B) HPLC peak intensities of QM1and CT02-H at various concentrations. (C) Reaction of CT02-H with monitored by HPLC–EC at 0, 2, and 10 min. XO (10 mU/ml) was added to the solution containing X (100 μM), DTPA (100 μM), and CT02-H (14 μM) in PBS; then, one aliquot was taken at 2 or 10 min and SOD (200 U/ml) was added to quench the reaction. For the sample at 0 min, SOD was introduced before addition of XO. The peaks of CT02-H at 2 and 10 min are shown with 10-fold higher gain because of the weak residual intensity. #These peaks come from the X/XO system (see Supplementary Fig. S11). (D) (a) HPLC chromatograms of the QM1 peaks centered at a retention time of 4.2 min, measuring the generation in BAECs stimulated by 0, 5, and 100 μM menadione in the presence of CT02-H (50 μM) for 15 min at 37 °C. (b) HPLC chromatograms of the QM1 peaks centered at a retention time of 4.2 min, measuring the generation in BAECs treated with anoxia/reoxygenation. After BAECs were exposed to anoxia for 24 h, CT02-H (50 μM) was added to the medium and then reoxygenation treatment was conducted for 5 min or 2 h. The medium was analyzed by HPLC. (E) Concentration effect of menadione on the cellular generation in BAECs.

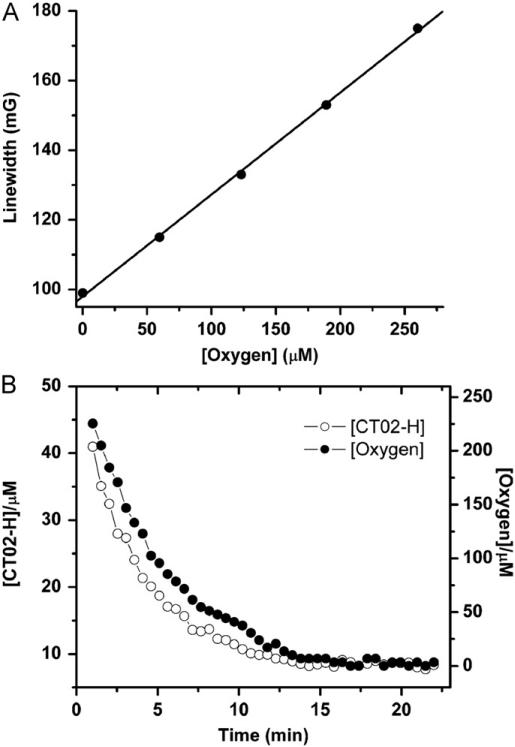

Like other TAM radicals, CT02-H can also serve as an O2 probe based on its O2-dependent EPR linewidth broadening. Fig. 12A shows the EPR line broadening of CT02-H as a function of the O2 concentration. Fig. 12B shows the changes in O2 and CT02-H concentration over time in the X/XO system. CT02-H gradually decayed, with the concomitant decrease in O2 concentration. Because the CT02-H concentration used (100 μM) is much higher than the concentration of , CT02-H largely outcompetes the self-dismutation and traps almost all of the generated during the first several minutes. Therefore, the initial decay rate of CT02-H is effectively equal to the initial generation rate. According to Fig. 12B, the rates of initial generation and consumption were calculated to be 4.9 and 20.7 μM/min, respectively, with the generation efficiency of ~24% from O2 in accordance with the range of values reported in the literatures [42,44,45]. Therefore, CT02-H can be used to simultaneously measure the O2 concentration and generation as well as the ratio of its generation to the O2 consumed.

Fig. 12.

(A) Variations in the EPR linewidth of the low-field peak of CT02-H with O2 concentration. (B) Simultaneous monitoring of O2 and TAM concentrations by EPR in the system containing CT02-H (100 μM), X (100 μM), XO (10 mU/ml), and DTPA (100 mM). The concentration of CT02-H was quantitated by comparing the double integral of the EPR signal of each radical with its predetermined concentration (i.e., 100 μM).

Discussion

The crucial role of in redox cell signaling and in the development of disease has resulted in an increasing need for development of new methodologies for the detection and quantification of this reactive species. However, currently available techniques for the measurement of are still limited by low sensitivity and specificity. In this study, we reported that the partially substituted TAM CT02-H can serve as a highly sensitive and specific probe suitable for measurements in biological systems.

It was shown in our previous study that OX063, a fully substituted TAM radical, can function as a probe with relatively high sensitivity and specificity [24]. Similar results were also observed for CT-03 [34]. Compared to OX063 and CT-03, CT02-H shows higher sensitivity to , due to the high reaction rate, but similarly high specificity (Fig. 6). Upon reaction with , CT02-H quickly loses its EPR signal (Figs. 2A and 2B) and is selectively transformed into the diamagnetic quinone methide QM1 (Fig. 5), which has a maximal absorbance at 540 nm (ε= 15,900 M−1 cm−1; Fig. 4), allowing spectrophotometric measurement of . Interestingly, the reaction of CT02-H with resulted in oxidative dehydrogenation instead of oxidative decarboxylation as observed for CT-03 and OX063 [26]. The rate constant of CT02-H with was estimated to be 5.7 times higher than that of CT-03 by concurrently monitoring their EPR signal decays induced by (Fig. 2D). Kinetic studies (Fig. 3) also showed that CT02-H has a reaction rate constant of 1.7 × 104 M−1 s−1, which is 5.5 times higher than that of CT-03 (3.1 × 103 M−1 s−1), consistent with the above value (5.7 times). The much higher reactivity of CT02-H with compared to CT-03 and OX063 (3.1 × 103 M−1 s−1) [24] is most likely due to the ease of oxidative dehydrogenation in CT02-H compared to the oxidative decarboxylation in CT-03 and OX063 because the hydrogen on the active carbon in CT02-H is less bulky than the carboxylate group in the other two TAMs, and the neutral nature of the hydrogen prevents the electrostatic repulsion with the negatively charged upon the reaction. Therefore, this new EPR probe exhibits higher sensitivity for than its fully substituted analogues CT-03 and OX063.

EPR spin trapping is one of the most sensitive and definitive methods for the detection of biological radicals, including . This technique utilizes the reaction of nitrone spin traps with resulting in the production of relatively stable spin adducts [15]. Our previous studies showed that the EPR spin trapping technique is more sensitive than the cytochrome c reduction method in quantifying [44,48]. However, the application of the EPR spin trapping method for very low fluxes is still limited because of slow spin trap reactivity with , and short adduct half-life, as well as decreased EPR analytical sensitivity due to the complex multiline EPR spectra of the spin adduct. In our experiments, generation was not detectable using DEPMPO, the most specific commonly used spin trap for , when a very low concentration of XO (0.05 mU/ml) was utilized. Comparatively, in the same system, induced a marked decrease in the EPR signal intensity (~75%) of CT02-H over 60 min (Fig. 9), indicating that CT02-H is well suited to the detection of low flux. Assuming that EPR spectroscopy can distinguish 5% of the signal decay, the detection limit of CT02-H in this experiment is estimated to be ~1.7 nM/min of the flux. With the use of an internal nonreactive standard such as the extremely stable dendritic trityl radical [34] or an external standard such as CT-03 or OX063, one can precisely measure as little as 2% of the signal intensity change by EPR, enabling detection of 2.5 times lower flux (i.e., 0.68 nM/min). With longer reaction time the detection limit would be expected to be further lowered in proportion to the time, with a value of as low as 0.34 nM/min after 120 min. Furthermore, owing to the high sensitivity, CT02-H can be used to detect from as few as 600 menadione-treated BAECs (0.04 ml × 1.5 × 104 cells/ml) over 20 min using an external or internal standard as mentioned above, which is 80 times lower than that (48,000 cells) required in the spin trapping method using DEPMPO as a spin trap. To further increase the sensitivity of the present EPR method for , fully deuterated CT02-H with deuteration of all of the methyl groups [49] and the aromatic hydrogen can be developed in the future.

On the other hand, HPLC in tandem with the highly sensitive electrochemical detection technique can be used to quantitate with a detection limit of 10 nM equating to measurement of a flux of only 0.17 nM/min for a 60-min measurement (Figs. 11A and 11B). Owing to the high sensitivity of this technique, the generation can be detected from BAECs that were stimulated by as low as 5 μM menadione (Figs. 11D and 11E). In addition, the generation in BAECs that were treated with anoxia/reoxygenation was also determined (Fig. 11D). Therefore, HPLC coupled with the use of CT02-H allows highly sensitive detection and measurement of the generation in various in vitro and ex vivo systems.

The high O2 sensitivity of CT02-H also allowed simultaneous measurement of the O2 consumption (20.7 μM/min) and generation (4.9 μM/min) in the X/XO system in a single experiment (Fig. 12). Thus, the magnitude of the measured generation corresponded to 24% of the total O2 consumption, which is in good agreement with values calculated from separate experiments using either CT02-H (28%) or cytochrome c (29%) (Fig. 8) and within the range of previously published values of 20– 30% [42,44,45].

Superoxide is the primary species formed during cellular oxidative stress and alkyl peroxyl radicals are secondary or terminal derivatives of that are mainly generated from lipids in cell membranes. Although the reaction of CT02-H with peroxyl radicals was also observed to a lesser extent than with superoxide (Fig. 6), this reaction would be unlikely to occur in cells and tissues because the negatively charged CT02-H remains outside the biomembrane. Therefore, CT02-H would be expected to provide high specificity for in biological systems. In fact, CT02-H exhibits much higher specificity for compared to most currently available fluorescence probes [50], especially with negligible interference from H2O2 and HO . Our prior strategy for stabilization of the TAM CT-03 could also be applied to further increase the specificity of CT02-H to [34]. Moreover, based on its good EPR properties, CT02-H and its derivatives are well suited to in vivo detection and imaging of with the use of low-frequency EPR spectroscopy and imaging [51–53].

In summary, our results showed that the partially substituted TAM radical CT02-H is highly sensitive for detection with good biostability. The negatively charged nature of CT02-H at neutral pH due to its two carboxylates prevents its cellular uptake, making it a specific extracellular probe. With further derivatization in the future, it should be possible to enable intracellular uptake, similar to what we have reported for other TAMs for which modification of the carboxylate groups to form acetoxymethoxy esters has allowed intracellular uptake and targeting [30,31]. The sharp doublet EPR signal of CT02-H enables detection of its levels and -dependent decay. Moreover, its O2-sensitive EPR line broadening also enables simultaneous measurement of the O2 concentration. The stable quinone methide product (QM1) formed by the reaction of CT02-H with can be quantitated by HPLC with electrochemical detection, providing an alternative method for highly sensitive measurement. CT02-H, with its high biostability and sharp doublet EPR spectrum, is well suited to in vivo EPR spectroscopy and imaging of and . Thus, this new probe provides a powerful tool for measuring and O2 in a wide variety of chemical and biological systems and provides important insights into the design of TAM-based superoxide probes with improved properties.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by NIH Grants HL38324, EB0890, EB4900 (J.L.Z.), and HL81248 (F.A.V.).

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.09.011.

References

- 1.Suzuki YJ, Forman HJ, Sevanian A. Oxidants as stimulators of signal transduction. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1997;22:269–285. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00275-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408:239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Droge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:47–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zweier JL, Talukder MAH. The role of oxidants and free radicals in reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006;70:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fridovich I. Superoxide radical—an endogenous toxicant. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1983;23:239–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.23.040183.001323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MTD, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007;39:44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galkin A, Brandt U. Superoxide radical formation by pure complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase) from Yarrowia lipolytica. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:30129–30135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504709200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kussmaul L, Hirst J. The mechanism of superoxide production by NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) from bovine heart mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:7607–7612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510977103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L, Yu LD, Yu CA. Generation of superoxide anion by succinate–cytochrome c reductase from bovine heart mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:33972–33976. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.33972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YR, Chen CL, Yeh A, Liu XP, Zweier JL. Direct and indirect roles of cytochrome b in the mediation of superoxide generation and NO catabolism by mitochondrial succinate–cytochrome c reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:13159–13168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513627200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown DI, Griendling KK. Nox proteins in signal transduction. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;47:1239–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen CA, Wang TY, Varadharaj S, Reyes LA, Hemann C, Talukder MAH, Chen YR, Druhan LJ, Zweier JL. S-glutathionylation uncouples eNOS and regulates its cellular and vascular function. Nature. 2010;468:1115–1521. doi: 10.1038/nature09599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boveris A, Chance B. The mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide: general properties and effect of hyperbaric oxygen. Biochem. J. 1973;134:707–716. doi: 10.1042/bj1340707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler J, Koppenol WH, Margoliash E. Kinetics and mechanism of the reduction of ferricytochrome-c by the superoxide anion. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:747–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villamena FA, Zweier JL. Detection of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species by EPR spin trapping. Antioxid. Redox Signaling. 2004;6:619–629. doi: 10.1089/152308604773934387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuasa M, Oyaizu K. Electrochemical detection and sensing of reactive oxygen species. Curr. Org. Chem. 2005;9:1685–1697. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wardman P. Fluorescent and luminescent probes for measurement of oxidative and nitrosative species in cells and tissues: progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007;43:995–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen XQ, Tian XZ, Shin I, Yoon J. Fluorescent and luminescent probes for detection of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:4783–4804. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15037e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han YB, Liu YP, Rockenbauer A, Zweier JL, Durand G, Villamena FA. Lipophilic beta-cyclodextrin cyclic-nitrone conjugate: synthesis and spin trapping studies. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:5369–5380. doi: 10.1021/jo900856x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardy M, Bardelang D, Karoui H, Rockenbauer A, Finet JP, Jicsinszky L, Rosas R, Ouari O, Tordo P. Improving the trapping of superoxide radical with a beta-cyclodextrin-5-diethoxyphosphoryl-5-methyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DEPMPO) conjugate. Chem.-Eur. J. 2009;15:11114–11118. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao HT, Joseph J, Fales HM, Sokoloski EA, Levine RL, Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B. Detection and characterization of the product of hydroethidine and intracellular superoxide by HPLC and limitations of fluorescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:5727–5732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501719102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsumoto K, English S, Yoo J, Yamada K, Devasahayam N, Cook JA, Mitchell JB, Subramanian S, Krishna MC. Pharmacokinetics of a triarylmethyl-type paramagnetic spin probe used in EPR oximetry. Magn. Reson. Med. 2004;52:885–892. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsumoto K, Subramanian S, Devasahayam N, Aravalluvan T, Murugesan R, Cook JA, Mitchell JB, Krishna MC. Electron paramagnetic resonance imaging of tumor hypoxia: enhanced spatial and temporal resolution for in vivo pO2 determination. Magn. Reson. Med. 2006;55:1157–1163. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rizzi C, Samouilov A, Kutala VK, Parinandi NL, Zweier JL, Kuppusamy P. Application of a trityl-based radical probe for measuring superoxide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003;35:1608–1618. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kutala VK, Parinandi NL, Zweier JL, Kuppusamy P. Reaction of superoxide with trityl radical: implications for the determination of super-oxide by spectrophotometry. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2004;424:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Decroos C, Li Y, Bertho G, Frapart Y, Mansuy D, Boucher JL. Oxidation of tris-(p-carboxyltetrathiaaryl)methyl radical EPR probes: evidence for their oxidative decarboxylation and molecular origin of their specific ability to react with . Chem. Commun. 2009;11:1416–1418. doi: 10.1039/b819259f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xia SJ, Villamena FA, Hadad CM, Kuppusamy P, Li YB, Zhu H, Zweier JL. Reactivity of molecular oxygen with ethoxycarbonyl derivatives of tetrathiatriarylmethyl radicals. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:7268–7279. doi: 10.1021/jo0610560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Laursen I, Leunbach I, Ehnholm G, Wistrand LG, Petersson JS, Golman K. EPR, D. N. P. properties of certain novel single electron contrast agents intended for oximetric imaging. J. Magn. Reson. 1998;133:1–12. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kutala VK, Parinandi NL, Pandian RP, Kuppusamy P. Simultaneous measurement of oxygenation in intracellular and extracellular compartments of lung microvascular endothelial cells. Antioxid. Redox Signaling. 2004;6:597–603. doi: 10.1089/152308604773934350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y, Villamena FA, Sun J, Xu Y, Dhimitruka I, Zweier JL. Synthesis and characterization of ester-derivatized tetrathiatriarylmethyl radicals as intracellular oxygen probes. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:1490–1497. doi: 10.1021/jo7022747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu YP, Villamena FA, Sun J, Wang TY, Zweier JL. Esterified trityl radicals as intracellular oxygen probes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;46:876–883. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bobko AA, Dhimitruka I, Zweier JL, Khramtsov VV. Trityl radicals as persistent dual function pH and oxygen probes for in vivo electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy and imaging: concept and experiment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:7240–7241. doi: 10.1021/ja071515u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dhimitruka I, Bobko AA, Hadad CM, Zweier JL, Khramtsov VV. Synthesis and characterization of amino derivatives of persistent trityl radicals as dual function pH and oxygen paramagnetic probes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:10780–10787. doi: 10.1021/ja803083z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y, Villamena FA, Zweier JL. Highly stable dendritic trityl radicals as oxygen and pH probe. Chem. Commun. 2008;36:4336–4338. doi: 10.1039/b807406b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Driesschaert B, Marchand V, Leveque P, Gallez B, Marchand-Brynaert J. A phosphonated triarylmethyl radical as a probe for measurement of pH by EPR. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:4049–4051. doi: 10.1039/c2cc00025c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu YP, Song YG, Rockenbauer A, Sun J, Hemann C, Villamena FA, Zweier JL. Synthesis of trityl radical-conjugated disulfide biradicals for measurement of thiol concentration. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:3853–3860. doi: 10.1021/jo200265u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu YP, Villamena FA, Rockenbauer A, Zweier JL. Trityl-nitroxide biradicals as unique molecular probes for the simultaneous measurement of redox status and oxygenation. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:628–630. doi: 10.1039/b919279d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu YP, Villamena FA, Song YG, Sun J, Rockenbauer A, Zweier JL. Synthesis of 14 N and 15 N-labeled trityl-nitroxide biradicals with strong spin–spin interaction and improved sensitivity to redox status and oxygen. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:7796–7802. doi: 10.1021/jo1016844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dhimitruka I, Velayutham M, Bobko AA, Khramtsov VV, Villamena FA, Hadad CM, Zweier JL. Large-scale synthesis of a persistent trityl radical for use in biomedical EPR applications and imaging. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:6801–6805. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bielski BHJ, Arudi RL, Sutherland MW. A study of the reactivity of with unsaturated fatty-acids. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:4759–4761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosen GM, Britigan BE, Halpern HJ, Pou S, editors. Free Radicals: Biology and Detection by Spin Trapping. Oxford Univ. Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fridovich I. Quantitative aspects of the production of superoxide anion radical by milk xanthine oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1970;245:4053–4057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Gelder BF, Slater EC. The extinction coefficient of cytochrome c. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 1962;58:593–595. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(62)90073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roubaud V, Sankarapandi S, Kuppusamy P, Tordo P, Zweier JL. Quantitative measurement of superoxide generation using the spin trap 5-(diethoxyphosphoryl)-5-methyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide. Anal. Biochem. 1997;247:404–411. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olson JS, Ballou DP, Palmer G, Massey V. Mechanism of action of xanthine-oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1974;249:4363–4382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Decroos C, Li Y, Bertho G, Frapart Y, Mansuy D, Boucher JL. Oxidative and reductive metabolism of tris(p-carboxyltetrathiaaryl)methyl radicals by liver microsomes. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2009;22:1342–1350. doi: 10.1021/tx9001379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosen GM, Freeman BA. Detection of superoxide generated by endothelial-cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:7269–7273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.23.7269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanders SP, Harrison SJ, Kuppusamy P, Sylvester JT, Zweier JL. A comparative-study of EPR spin-trapping and cytochrome-c reduction techniques for the measurement of superoxide anions. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1994;16:753–761. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dhimitruka I, Grigorieva O, Zweier JL, Khramtsov VV. Synthesis, structure and EPR characterization of deuterated derivatives of Finland trityl radical. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;132:3946–3949. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kalyanaraman B, Darley-Usmar V, Davies KJA, Dennery PA, Forman HJ, Grisham MB, Mann GE, Moore K, Roberts LJ, Ischiropoulos H. Measuring reactive oxygen and nitrogen species with fluorescent probes: challenges and limitations. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012;52:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuppusamy P, Chzhan M, Vij K, Shteynbuk M, Lefer DJ, Giannella E, Zweier JL. Three-dimensional spectral–spatial EPR imaging of free radicals in the heart: a technique for imaging tissue metabolism and oxygenation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:3388–3392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.He G, Shankar RA, Chzhan M, Samouilov A, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL. Noninvasive measurement of anatomic structure and intraluminal oxygenation in the gastrointestinal tract of living mice with spatial and spectral EPR imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:4586–4591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuppusamy P, Wang P, Chzhan M, Zweier JL. High resolution electron paramagnetic resonance imaging of biological samples with a single line paramagnetic label. Magn. Reson. Med. 1997;37:479–483. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910370402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.