Abstract

Background: Malignant ascites is a common complication seen in association with various types of neoplastic processes. Due to high recurrence rates, patients may require multiple paracenteses, which have associated complications such as increased risk of bleeding, infection, pain, and volume and electrolyte depletion.

Objective: This study evaluated the management of malignant ascites by placement of the PleurX® tunneled catheter system at a single center.

Methods: This was a retrospective study of 38 patients who underwent PleurX catheter placement for refractory malignant ascites between February 2006 and March 2012 at our institution. Pretreatment characteristics and outcome measures were reported using descriptive statistics.

Results: The population included 21 males and 17 females with a mean age of 60.6 years (range, 36–79 years) diagnosed with metastatic disease from a variety of primary malignancies, the most common of which was pancreatic cancer (10 patients). In 84% of patients (32/38) who were not lost to follow-up, mean survival time was 40.7 days (range 4–434 days). Technical success rate of catheter placement was 100%.

Conclusions: The PleurX catheter can be used to manage malignant ascites in severely ill patients with metastatic cancer, with a high rate of procedural success and a low incidence of potentially serious adverse events, infections, or catheter-related complications.

Introduction

Ascites, the pathological collection of fluid in the peritoneal cavity, is a common complication of malignancy, liver cirrhosis, and other serious medical conditions. Malignant ascites develops in as many as 50% of patients with cancer, and is especially common among those with cancers of the pancreas, liver, biliary tract, ovary, colon, lymphatic system, uterus, or cervix.1,2 Ascites develop as a result of the dissemination of malignant cells within the peritoneal cavity (carcinomatosis), which obstruct peritoneal lymphatics and the flow of large molecules and fluid from the peritoneal cavity circulatory system.3 Cancer cells also release cytokines that increase peritoneal capillary permeability, resulting in increased protein concentration of the peritoneal fluid.4 Patients with liver metastases may also develop ascites as a consequence of increased portal hypertension, which results in the efflux of protein from the intravascular compartment to the intraperitoneal space.3,5 Sequelae associated with malignant ascites may include abdominal pain, dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, and anorexia.3

Traditional interventions for malignant ascites have included repeated percutaneous drainage and peritoneovenous shunt placement. Although paracentesis provides temporary improvement in symptoms of nausea, vomiting, dyspnea, and abdominal discomfort for approximately 93% of patients,3 symptoms often return within 72 hours, and most patients require repeated treatment within 2 weeks.6,7 Potential complications include depletion of protein and electrolytes, pain, hypotension, peritonitis, bowel perforation, and hemorrhage.3,8 Protein loss may exacerbate or accelerate cancer-associated cachexia.7 Peritoneovenous shunts (e.g., a Denver shunt) transfer fluid from the peritoneal cavity to the systemic circulation through a one-way compressible valve system.9 Fluid is maintained within the body, minimizing protein and electrolyte loss and reducing patient discomfort associated with repeated paracentesis.9 This technique permits home management, but requires careful patient selection and postprocedure management to avoid serious complications from fluid overload (e.g., cardiac congestion and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy).10

The PleurX® catheter (CareFusion Corporation, San Diego, CA) makes it possible for patients with malignant pleural effusions or ascites to perform intermittent fluid drainage with no physician supervision and no further paracentesis. Benefits of the PleurX drainage system include the ability to perform repeated drainage of ascitic fluid at home, allowing greater patient independence and flexibility; better control of symptoms such as breathlessness, nausea, bloating, and abdominal pain; reduced need for large-volume paracentesis and the associated risk of infection; and resource savings by potential reduction in provider visits, nurse time, or hospital stays.11 Previous studies have reported reduced ascites-related symptoms, and reduced serum albumin in patients undergoing PleurX catheter placement for palliation of malignant ascites, with low rates of infection or procedural complications.12–14

The PleurX catheter system has also been shown to reduce the need for frequent hospital visits for percutaneous drainage, with an overall per-patient complication rate similar to that of paracentesis.8 This study describes the implantation success rate, short-term fluid drainage, procedural complications, and adverse events among patients with malignant ascites who underwent PleurX catheter system placement at a single institution.

Methods

In this institutional review board-approved study, patients with malignant ascites who required large-volume paracentesis and who were subsequently referred for placement of a tunneled PleurX catheter were retrospectively identified. Patients had undergone at least one paracentesis procedure before selection for the PleurX placement procedure.

PleurX placement

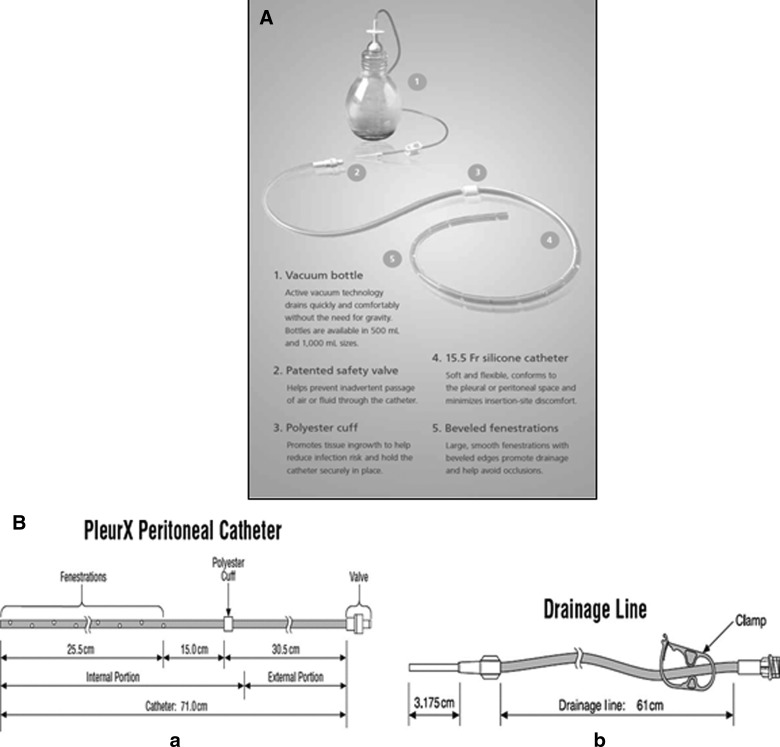

The PleurX and Aspira® (Bard Access Systems, Salt Lake City, UT) systems are more recent options for the home management of recurrent pleural effusions and malignant ascites. The PleurX system, which is commonly used in our practice, is a 15.5 French (15.5F) catheter with 30 beveled fenestrations along its distal 26 cm. The components of the catheter system are shown in Figure 1 (A, B). The catheter is constructed of silicone with a Dacron® cuff, which is approximately 36 cm from the tip. It has a proprietary safety valve that is designed to prevent the passage of air or fluid in either direction unless the valve is accessed with a specially designed, proprietary drainage line.12 The drainage system consists of a 500-mL or 1000-mL vacuum bottle with a drainage line connecting to the peritoneal catheter, as well as a procedure pack that includes supplies needed to perform the drainage procedure using sterile technique and to replace the cap and gauze dressing over the catheter. Drainage is performed when needed by attaching the vacuum bottle drainage line to the catheter drainage tube. When the seal is broken on the collection bottle, the vacuum bottle drains the fluid automatically. When drainage is completed, the patient disconnects the drainage line and applies a new adhesive dressing to cover the external portion of the catheter.

FIG. 1.

(A) The components of the PleurX catheter system, including the indwelling catheter and the vacuum drainage bottle. (B) The PleurX catheter and drainage line.

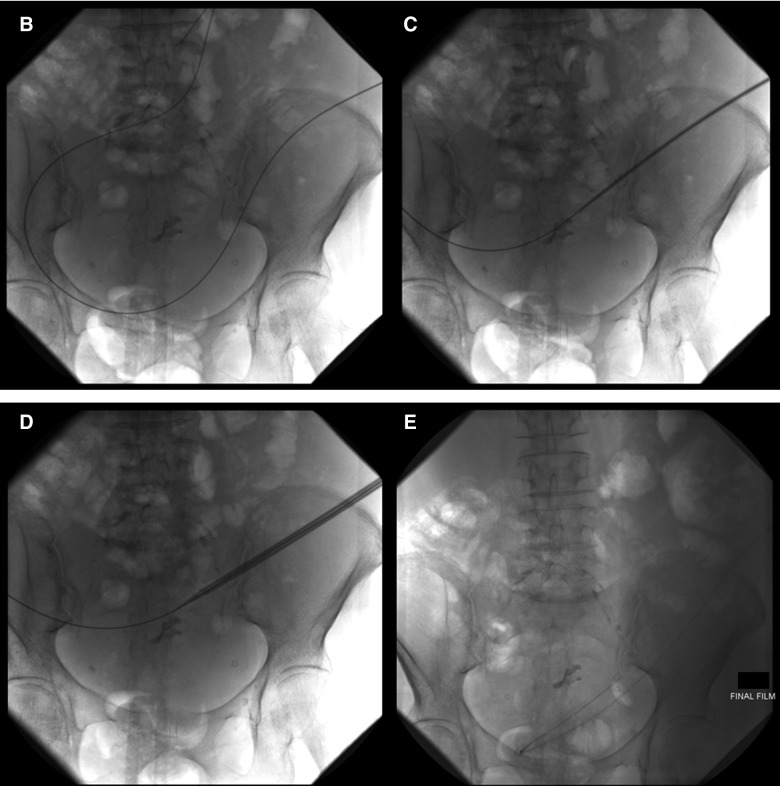

A limited ultrasound (US; 24 patients; Fig. 2A) or in some cases a limited computed tomography (CT) scan (14 patients) of the abdomen was performed and an entry site approximately 6 cm to 10 cm below the costal margin, lateral to the midline, was chosen. Lidocaine (1%) was injected subcutaneously at the site of the drain insertion and along the proposed track of the tunneled line. Conscious sedation with 1 mg to 2 mg of midazolam and 25 mcg to 50 mcg of fentanyl was used if requested by the patient (29 of 38 patients.) A 19-gauge Yueh Needle (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN) and sheath assembly attached to a syringe was inserted gradually into the abdomen. Upon fluid return the sheath was advanced and the needle was removed. A guidewire was inserted into the peritoneal cavity through the sheath (Fig. 2B). A small incision was made in the skin at the guidewire insertion site and then another incision was made 4 cm to 5 cm superiorly and medially. The fenestrated end of the catheter was attached to the tunneler, which was passed subcutaneously from the superior incision to the guidewire insertion site. The catheter was drawn through the tunnel until the Dacron cuff was approximately 1 cm inside the tunnel, and then the tunneler was removed. The Yueh sheath was removed over the wire, and serial dilation was performed; 8F and 12F dilators were provided in the PleurX peritoneal catheter kit (Fig. 2C). The dilation was followed by the placement of a 16F peel-away introducer over the guidewire into the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 2D). Once the guidewire and the dilator from the 16F peel-away introducer sheath had been removed, the fenestrated end of the catheter was advanced through the peel-away introducer until all the fenestrations were within the peritoneal cavity. The peel-away introducer was then removed (Fig. 2E). The incisions were sutured closed and the catheter secured in place. Placement of the PleurX peritoneal catheter is illustrated in Figure 3.

FIG. 2.

(A) Ultrasound of the left midabdomen showing a large volume of ascites. (B) Advancement of a 0.035 inch guidewire into the peritoneal cavity through the 19-guage Yueh sheath under fluoroscopic guidance. (C) Serial dilation over the guidewire. (D) Advancement of the 16F peel-away introducer sheath. (E) Final position of the catheter in the peritoneal cavity.

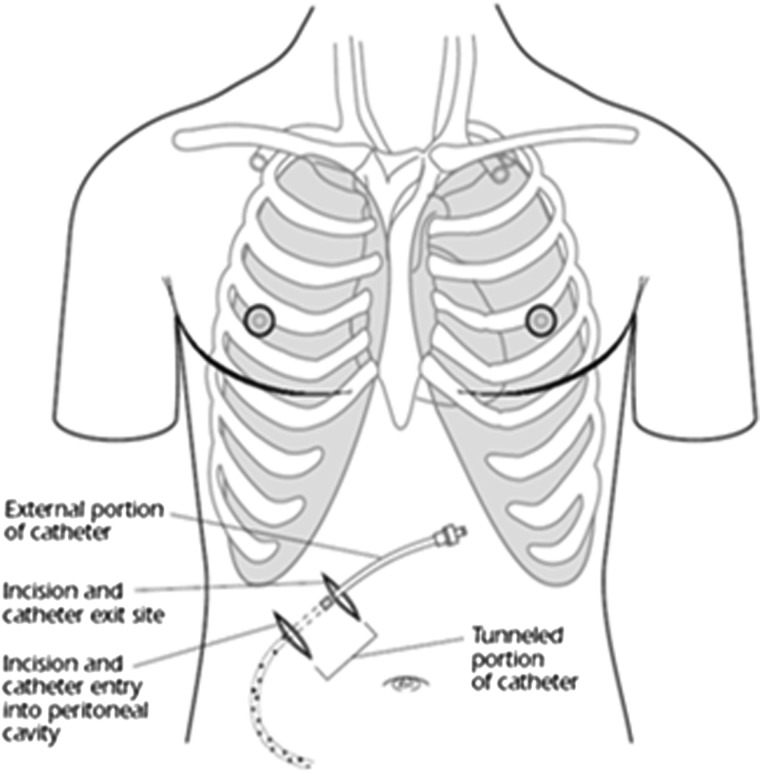

FIG. 3.

Placement of the PleurX peritoneal catheter.

The patient or caregiver was shown an educational training video and was given the instructions for proper catheter management and drainage immediately after catheter placement. Most patients were discharged home for self-care with the help of a family member or home health care, or to hospice. The remainders were managed in house until discharge.

Patient charts were retrospectively reviewed by a single reviewer, who collected the following information: patient age, sex, diagnosis, date of death or last follow-up evaluation for patients who were lost to follow-up, PleurX placement date, dates of subsequent procedures (if required), device-related complications, other complications or adverse events, number of paracentesis episodes before PleurX placement, fluid drained at each paracentesis episode, volume of ascitic fluid drained in the 24 hours after PleurX placement, documentation of patient training to perform PleurX drainage, and discharge destination (e.g., home or hospice). If the patient had home health care, then any complications or adverse events were recorded and the patient returned to the department of interventional radiology for evaluation. Technical success was defined as successful placement of the catheter and drainage of ascites after placement. Pretreatment characteristics and outcome measures were reported using descriptive statistics.

Results

Thirty-eight consecutive patients underwent PleurX catheter placement for refractory malignant ascites between February 6, 2006 and March 19, 2012 at a single institution. The patient population included 21 males and 17 females, who varied in age from 36 to 79 years (mean, 60.6 years). Patients were diagnosed with metastatic disease associated with a variety of primary malignancies, the most common of which included pancreatic cancer (10 patients), breast cancer (7 patients), hepatocellular carcinoma (6 patients), colorectal cancer (5 patients), and cholangiocarcinoma (5 patients). Survival time after catheter placement was available for 32 of the 38 patients (84%), and varied from 4 to 434 days (mean survival time, 40.7 days). Patients underwent a mean of three paracentesis procedures before PleurX placement (range, 1–12 procedures). The mean volume drained by paracentesis was 4078 mL per paracentesis procedure (range, 40 mL to 9500 mL) and a total of 12,000 mL per patient (range, 1000 mL to 48,000 mL). Twenty-four catheters were placed using US guidance and 14 catheters were placed using CT guidance as per operator preference. The technical success rate of catheter placement was 100%. The volume and frequency of PleurX drainage during the first 24 hours after placement was available for 37 of the 38 patients. The mean fluid volume drained during the first 24 hours was 3735 mL (range, 800 mL to 4000 mL). Thirty-four patients underwent a single PleurX catheter drainage within the first 24 hours of placement; 3 patients underwent two drainage sessions. Twelve patients' required additional procedures to check, remove, correct, or replace the PleurX catheter, with a mean time from initial placement of 38.7 days (range, 2 to 106 days). Two patients required catheter check (at days 13 and 17, respectively) with no further procedures. PleurX catheter replacements were performed for 2 patients with catheter leakage after 10 and 15 days, respectively. One patient underwent PleurX catheter removal as the patient elected to have a peritoneovenous shunt placed after 76 days. One patient required catheter repair without replacement after 50 days. Six patients underwent catheter removal after a mean of 50.3 days (range, 2 to 106 days) without replacement: 2 due to infection after 2 days and 62 days, respectively and 2 because they were not draining after 41 days and 106 days, respectively. One patient's catheter was out of place 21 days after the initial placement procedure. The catheter was removed due to insufficient ascitic fluid. Finally, one catheter was removed after 70 days for an unspecified reason. Postprocedural complications between the time of PleurX placement and the time of death or last follow-up examination are summarized in Table 1. The majority of the procedures were performed in the outpatient setting. Twelve of the patients were already admitted when PleurX catheter placement was requested; the mean hospital stay was after placement was 3.75 days.

Table 1.

Postprocedural Complications Recorded between Time of PleurX Catheter Placement and Death or Last Follow-Up Examination

| Event | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Catheter site leakage | 2 |

| Catheter pulled out | 1 |

| Pain | 3 |

| Infection | 2 |

| White blood cell abnormalities | 3 |

| Sleep disturbance | 1 |

Twenty-seven of the patients were discharged to home, 6 were discharged to hospice, and discharge destination was not recorded for the remaining 5 patients. Patient charts indicated that 23 of the patients were successfully trained to perform PleurX drainage, 1 patient declined training, and information about training was not available for the remaining 14 patients.

Discussion

Treatment of malignant ascites is an end-of-life procedure for most patients, and is intended to palliate symptoms. Patients with advanced cancer often experience significant pain and fatigue, and they may delay hospital visits for large-volume paracentesis until fluid has accumulated to an intolerable level.8 Peritoneovenous shunting is another option for patients with malignant ascites, although many patients with advanced cancer may not be eligible for this procedure.9 The PleurX catheter system was approved in 2005 for the intermittent drainage of symptomatic, recurrent, malignant ascites that does not respond to medical management of the underlying disease; and for palliation of symptoms related to recurrent malignant ascites. The PleurX catheter is not approved for nonmalignant ascites, and it is contraindicated when the peritoneal cavity is multiloculated and the drainage of a single loculation would not be expected to provide relief of dyspnea or other symptoms, in the setting of coagulopathy, or when the peritoneal cavity is infected.15

Previous studies of patients with malignant ascites have demonstrated reduced mean serum albumin after PleurX catheter placement,12 with patients successfully draining their ascites at home with no further need for paracentesis and with a complication rate equal to that of repeat paracentesis.8,13 Patients reported satisfaction with the PleurX catheter system, including ease of drainage, lack of procedural pain, and ability to drain ascites before symptoms related to large fluid volumes occurred.8 In a report of their experience with 10 patients, Richard and colleagues did not report any catheter-related infections but had two catheters removed as they were no longer needed, one was pulled out by a patient but was not replaced and one catheter was treated with tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) to unclog it.12 In a prospective, multicenter clinical trial by Courtney and coworkers14 of 34 patients with recurrent malignant ascites, technical success of placement was 100%. Four patients required multiple interventions to unclog the catheter ranging from tPA administration to wire manipulation to maintain patency. There were two cases of infection. Seven patients reported leakage of ascites around the catheter. This prospective study reported that more than 80% of patients stated their ascites was well controlled with the PleurX catheter.14 PleurX catheter placement reduced patient-rated bloating, abdominal discomfort, diarrhea, and nausea after 2 to 8 weeks.14 A recent study by Tapping et al. reported a PleurX catheter success rate of 100% with no procedure-related deaths or major complications. Twenty-eight patients with refractory malignant ascites were followed until death allowing evaluation of factors contributing to minor complications.16 Drains remained in place and patent for a mean of 113 days (range, 5 to 365 days).16 Predictors of postprocedural complications included current chemotherapy, low hemoglobin, low albumin, high C-reactive protein, and high white blood cell (WBC) count. Four catheters were dislodged and replaced on the opposite side. Three patients had leaking around the catheter. Three patients had mild erythema around the catheter managed by oral antibiotics. No systemic infection developed.16

In our experience of 38 patients with recurrent malignant ascites, the PleurX peritoneal catheter system was successfully implanted in all patients. Adverse events included two cases of catheter-related infection and two cases of catheter leakage. One catheter was inadvertently pulled out by the patient, the other had leakage around the catheter 6 days after placement, which resolved after placement of a purse-string suture and (Dermabond, Ethicon, NJ). These rates are comparable to those reported in previous series, discussed above.

Other postprocedural events included infection, pain, WBC abnormalities, and sleep disturbance, all of which are common among severely ill patients with metastatic disease. The majority of cases were performed on an outpatient basis, and most of the patients were successfully trained to perform fluid drainage at home.

An evidence review by The United Kingdom (UK) National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recently concluded that the case for adopting the PleurX peritoneal catheter drainage system by the UK National Health System (NHS) is supported by evidence suggesting that the system is clinically effective, is associated with a low complication rate, and has the potential to improve patient quality of life.11 The PleurX system was associated with an estimated cost savings of £679 per patient when compared with inpatient large-volume paracentesis.11

An alternative to the PleurX system is the Aspira system, which has a few, key, minor differences compared with the PleurX catheter. The Aspira catheter includes an inner stylet that minimizes fluid leakage on advancement of the catheter into the peritoneal cavity. Instead of bottles, the Aspira system connects to a low-vacuum siphon pump that drains into a bag. Aspira internal data report that the system drains faster due to a larger diameter at its narrowest point.17

Potential limitations of this study include the use of a single-group design and retrospective chart review and the lack of prospectively evaluated outcome measures. The retrospective chart review did not permit detailed assessments of long-term outcomes, symptom relief, effects on serum albumin, or other results that might potentially have been of interest in this patient population.

Conclusions

The PleurX catheter system provides an alternative to large-volume paracentesis that may reduce the number of hospital visits for patients with advanced cancer. Catheter placement and management can be performed in the outpatient setting; placement was associated with a 100% short-term success rate. Adverse events were often minor including leakage of ascites around the catheter and catheter obstruction or dislodgement. There was a very low incidence of infection similar to that reported in the literature. The catheter permitted the drainage of large fluid volumes of malignant ascites for most patients in the comfort of their home.

Acknowledgments

Writing and editorial support provided by Mark P. Bowes, PhD, and CareFusion Corporation.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Garrison RN, Kaelin LD, Galloway RH, Heuser LS: Malignant ascites. Clinical and experimental observations. Ann Surg 1986;203:644–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parsons SL, Lang MW, Steele RJ:Malignant ascites: A 2-year review from a teaching hospital. Eur J Surg Oncol 1996;22:237–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sangisetty SL, Miner TJ: Malignant ascites: A review of prognostic factors, pathophysiology and therapeutic measures. World J Gastrointest Surg 2012;4:87–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Granis FW, Lai L, Takuka JT, Cullinane CA: Fluid complications. In: Pazdur R. (ed), Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2003, pp 997–1012 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon FD: Ascites. Clin Liver Dis 2012;16:285–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jatoi A, Nieva JJ, Qin R, et al. : A pilot study of long-acting octreotide for symptomatic malignant ascites. Oncology 2012;82:315–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markman M: Palliation of symptomatic malignant ascites: An (often) unmet need. Oncology 2012;82:313–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenberg S, Courtney A, Nemcek AA, Jr, Omary RA: Comparison of percutaneous management techniques for recurrent malignant ascites. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2004;15:1129–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zanon C, Grosso M, Aprà F, et al. : Palliative treatment of malignant refractory ascites by positioning of Denver peritoneovenous shunt. Tumori 2002;88:123–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Won JY, Choi SY, Ko HK, Kim SH, Lee KH, Lee JT, Lee do Y: Percutaneous peritoneovenous shunt for treatment of refractory ascites. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2008;19:1717– 1722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute for Health and Clinical Evidence: The PleurX peritoneal catheter drainage system for vacuum-assisted drainage of treatment-resistant, recurrent malignant ascites. March2012. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/MTG9/Guidance/pdf/English (Last accessed December10, 2012) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Richard HM, 3rd, Coldwell DM, Boyd-Kranis RL, Murthy R, Van Echo DA: PleurX tunneled catheter in the management of malignant ascites. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2001;12:373–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iyengar TD, Herzog TJ: Management of symptomatic ascites in recurrent ovarian cancer patients using an intra-abdominal semi-permanent catheter. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2002;19:35–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Courtney A, Nemcek AA, Jr, Rosenberg S, Tutton S, Darcy M, Gordon G: Prospective evaluation of the PleurX catheter when used to treat recurrent ascites associated with malignancy. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2008;19:1723–1731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.PleurX Peritoneal Catheter Kit [Instructions for Use]. McGaw Park, IL: CareFusion, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tapping CR, Ling L, Razack A: PleurX drain use in the management of malignant ascites: Safety, complications, long-term patency and factors predictive of success. Br J Radiol 2012;85:623–628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bard Access Systems Inc. Internal data. www.myaspira.com (Last accesed February3, 2013)