Abstract

Chlamydia (C.) pecorum, an obligate intracellular bacterium, may cause severe diseases in ruminants, swine and koalas, although asymptomatic infections are the norm. Recently, we identified genetic polymorphisms in the ompA, incA and ORF663 genes that potentially differentiate between high-virulence C. pecorum isolates from diseased animals and low-virulence isolates from asymptomatic animals. Here, we expand these findings by including additional ruminant, swine, and koala strains. Coding tandem repeats (CTRs) at the incA locus encoded a variable number of repeats of APA or AGA amino acid motifs. Addition of any non-APA/AGA repeat motif, such as APEVPA, APAVPA, APE, or APAPE, associated with low virulence (P<10−4), as did a high number of amino acids in all incA CTRs (P = 0.0028). In ORF663, high numbers of 15-mer CTRs correlated with low virulence (P = 0.0001). Correction for ompA phylogram position in ORF663 and incA abolished the correlation between genetic changes and virulence, demonstrating co-evolution of ompA, incA, and ORF663 towards low virulence. Pairwise divergence of ompA, incA, and ORF663 among isolates from healthy animals was significantly higher than among strains isolated from diseased animals (P≤10−5), confirming the longer evolutionary path traversed by low-virulence strains. All three markers combined identified 43 unique strains and 4 pairs of identical strains among all 57 isolates tested, demonstrating the suitability of these markers for epidemiological investigations.

Background

Chlamydia (C.) pecorum, a Gram-negative obligate intracellular bacterium, is a species of the genus Chlamydia belonging to the family Chlamydiaceae [1]. C. pecorum strains have been isolated worldwide from ruminants and swine with conjunctivitis, encephalomyelitis, enteritis, pneumonia, polyarthritis, abortion, and reproductive or urinary tract diseases [2]–[4]. More recent studies have shown that wild animals may also be infected with C. pecorum, most prominently Australian marsupials, such as koalas, in which fertility is severely compromised by urogenital infections [5], and western barred bandicoots with conjunctivitis [6]. C. pecorum is also found in the conjunctiva, intestine, and vaginal mucus of clinically healthy ruminants and swine [7]–[9]. In fact, such asymptomatic C. pecorum infections are found very frequently, particularly in ruminants at high population density where prevalence rates can approach 100% [10], [11], but also in pigs [12]. While high C. pecorum infectious loads associate significantly with disease symptoms [13], the majority of C. pecorum infections are asymptomatic and very low infectious loads are detected [8]–[10]. Nevertheless, even such asymptomatic infections of calves cause detectable lung dysfunction [14] and incur substantial reductions in weight gains [15]. Collectively, these observations raise the question if the parallel occurrence of asymptomatic and clinically manifest C. pecorum infections associates with virulence differences of strains that can be detected and characterized.

For several decades, serotyping using polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies in micro-immunofluorescence assays was used to characterize and classify individual chlamydial strains. Meanwhile, genotyping based on PCR and sequencing of ompA has gradually replaced serotyping. Indeed, several new methods were proposed, such as DNA microarray testing [16], multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) [17] and typing based on variable number tandem repeats (VNTR) [18]. However, none of these methods is congruent with the virulence of chlamydial isolates, although some parameters are correlated with clinical manifestations and serotyping. For C. trachomatis, in a study including 175 men and 135 women attending a sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinic, a correlation was reported between urethral discharge in men and serotypes H and J, and between lower abdominal pain in women and serotypes F and G [19]. Furthermore, 47.5% of asymptomatic patients were infected with C. trachomatis serovar E among 1,770 STD-infected women in China [20]. As to C. psittaci, serovar D strains induce the most severe disease in turkeys [21].

C. pecorum strains present many genetic and antigenic variations [22], [23]. In earlier investigations, we found virulence-associated genetic differences among 19 C. pecorum strains by identifying different motifs of the variant coding tandem repeats (CTR) in incA of isolates from sick versus healthy ruminants [24]. By determining lower numbers of repetitions of the CTR in the hypothetical ORF663 in highly virulent C. pecorum strains than in low-virulence isolates, we further identified virulence-associated genetic polymorphisms of C. pecorum [25]. In addition, 6 out of 8 strains from diseased ruminants clustered to a single ompA sequence group [25].

In this study we further investigated the C. pecorum segregation by virulence in ompA, incA, and ORF663. These loci were sequenced for an expanded panel of C. pecorum isolates from most known hosts of C. pecorum, including 11 strains isolated from swine, 24 additional strains isolated from ruminants, and 3 strains isolated from koalas. Virulence associations of incA and ORF663 CTRs were confirmed and expanded to porcine and koala C. pecorum isolates, and low virulence significantly associated with evolutionary distance of ompA, incA, and ORF663 from the respective putative C. pecorum ancestor.

Results

Sequence analysis of ompA, incA and ORF663

All 32 strains yielded the expected amplification products of ompA, incA, and ORF663, except for two bovine strains (DC49 and DC55) that failed to give an incA and one porcine strain (R106) that failed to give an ORF663 amplicon (Table 1). Sequence analysis of incA showed that all 11 porcine strains had one encoded motif (APA) with 7 to 14 repetitions representing 7 variants (Table 1). Similarly, the 3 koala strains with recently deposited genomes showed 4–11 repetitions of the APA motif. In addition, a new motif of 9 nucleotides (GCTGGAGCC) encoding amino acids alanine and glycine AGA (Motif 5) was identified. This motif was detected only in 3 bovine strains isolated from different geographical areas and associated with different conditions (DC13, 2047, 66P130; Table 1).

Table 1. Sequence coding tandem repeat characteristics and accession numbers for all C. pecorum strains analyzed in this study.

*Strains sequenced in this study. Strains not marked with an asterisk were sequenced in a preceding study [23], or posted as complete genomes [30]–[32].

Referenced in [31].

Referenced in [2].

Referenced in [42].

Referenced in [30].

Isolated by M. Dawson, Virology Department, Central Veterinary Laboratory, Weybridge UK.

Isolated at INRA, UR1282, Infectiologie Animale et Santé Publique, Centre de Recherche de Tours, France.

Referenced in [43].

Referenced in [32].

Referenced in [3].

Supplied by Konrad Sachse, Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut Jena, OIE and National Reference Laboratory for Chlamydiosis, 07743 Jena, Germany, 07743 Jena, Germany.

Supplied by Simone Magnino, Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale della Lombardia e dell’Emilia Romagna “Bruno Ubertini”, National Reference Laboratory for Animal Chlamydioses, Sezione Diagnostica di Pavia, 27100 Pavia, Italy.

Isolated by M.S. McNulty, Veterinary Research Laboratory, Stormont, Belfast, Ulster.

-not amplified by PCR.

Similar to the ruminant strains isolated from diseased animals, the 10 porcine strains and 3 koala strains, all from diseased hosts, possessed lower numbers of ORF663 CTR repetitions (<43 repeats) than most intestinal strains isolated from asymptomatic (healthy) ruminants (Table 1). Strains isolated from asymptomatic ruminants (n = 19) had more than 43 repeats, except for 6 strains isolated from cattle and one strain isolated from sheep (Table 1).

Correlation of ompA with virulence

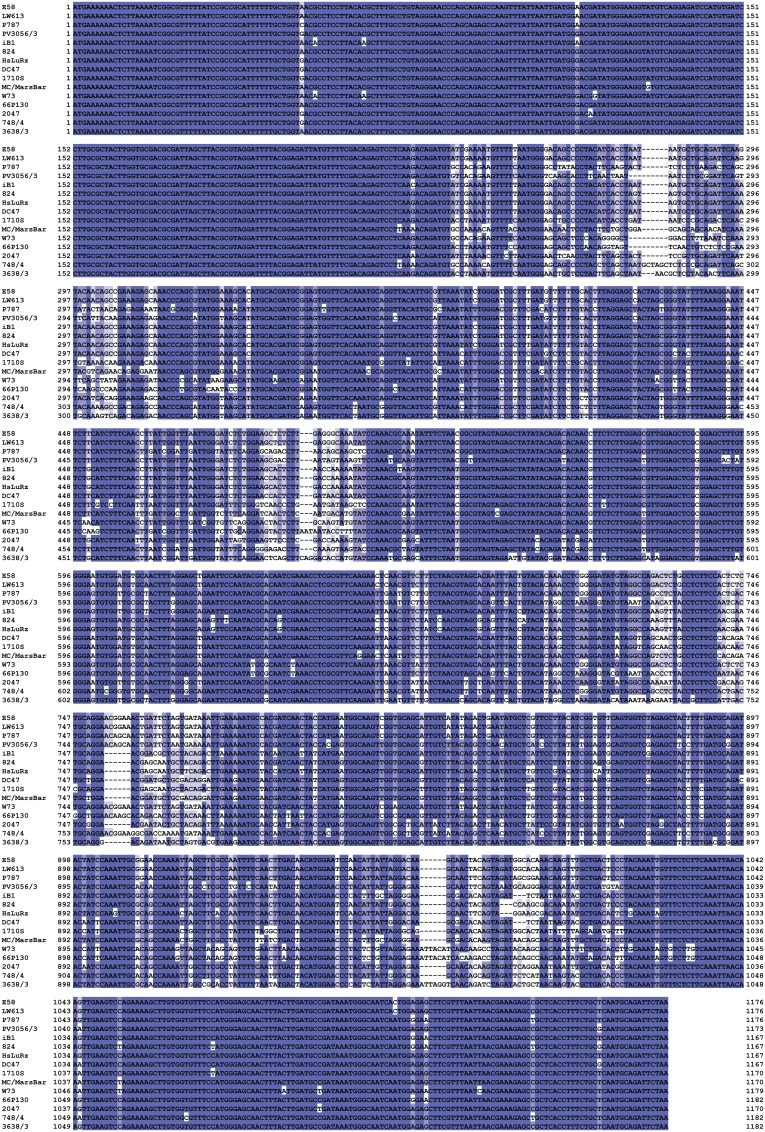

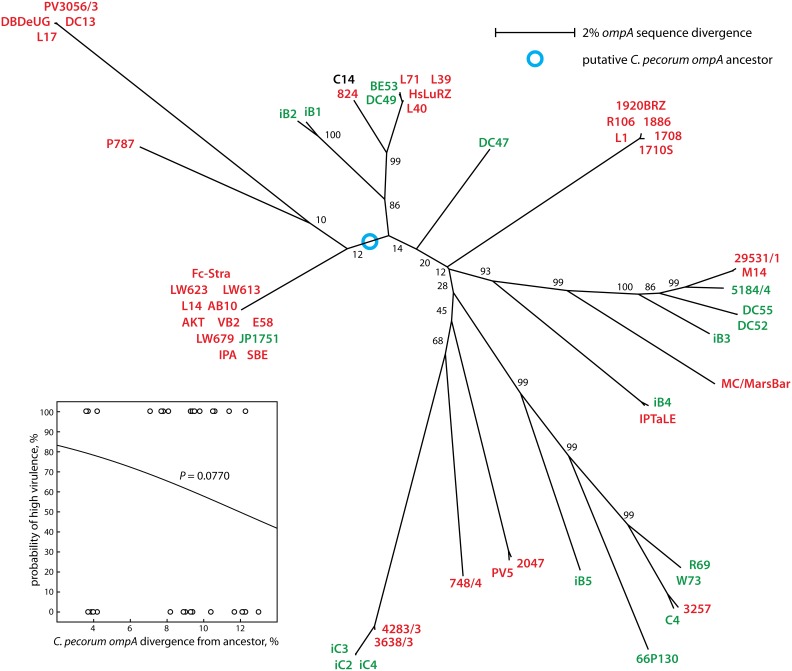

The chlamydial ompA is one of the most polymorphic of all genes conserved throughout the genus Chlamydia, and therefore frequently used as surrogate for approximating overall evolution of chlamydial genomes. This diversity is based not on variation in repeat elements, but on frequent recombination within the 4 variable domains of the gene [25]. We therefore used ompA to estimate the correlation between C. pecorum genomic diversity with virulence. We first aligned the complete ompA sequences of all 57 C. pecorum strains used in this study (Figure 1; Figure S1) and performed neighbor-joining phylogenetic reconstruction of their evolution. The resultant phylogram in Figure 2 arranged the ompA genes into several clusters of closely related sequences (clades) that were separated from other clades by deep and strongly bootstrap-supported branches [25].

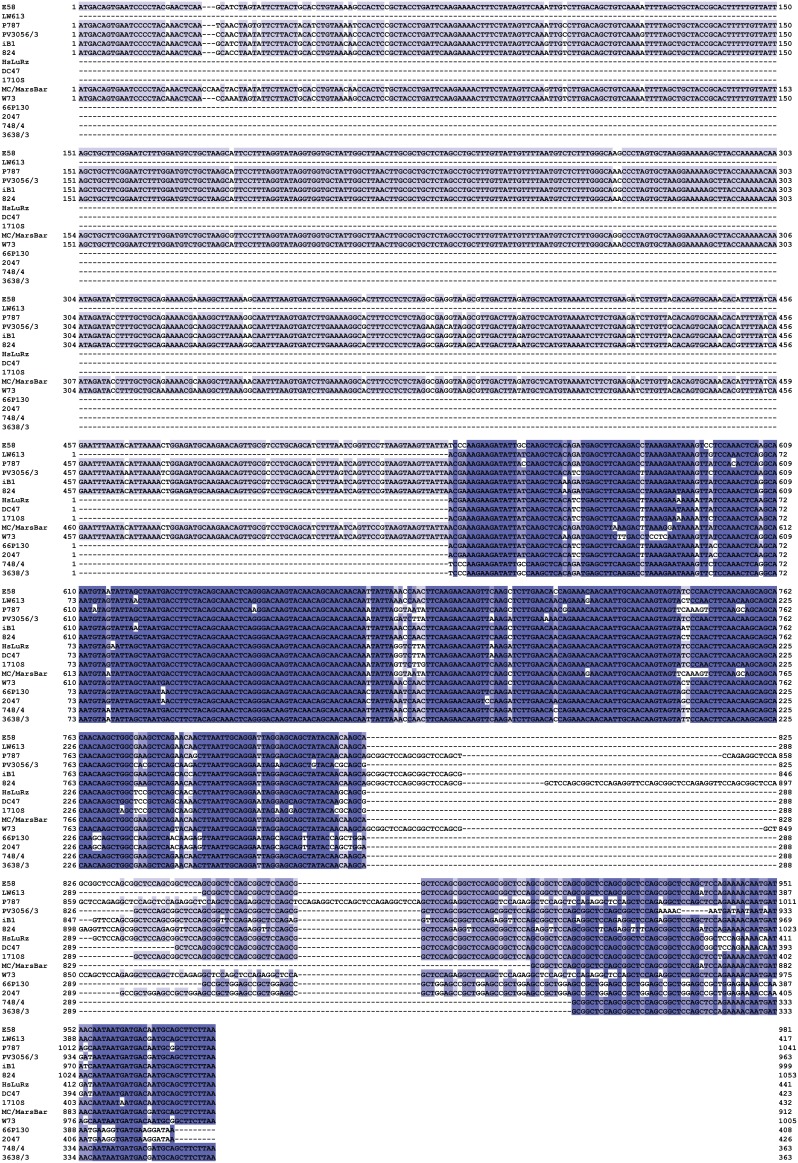

Figure 1. C. pecorum ompA alignment.

A subset of the 57 analyzed C. pecorum strains was selected that represents all major clades of the phylogram in Figure 2. The corresponding sequence alignment of the complete ompA of all 57 strains was used to infer C. pecorum ompA evolution by construction of a phylogenetic tree. The alignment of the resultant amino acid sequences of all 57 C. pecorum OmpA proteins deduced from the nucleotide sequences is shown in Figure S1.

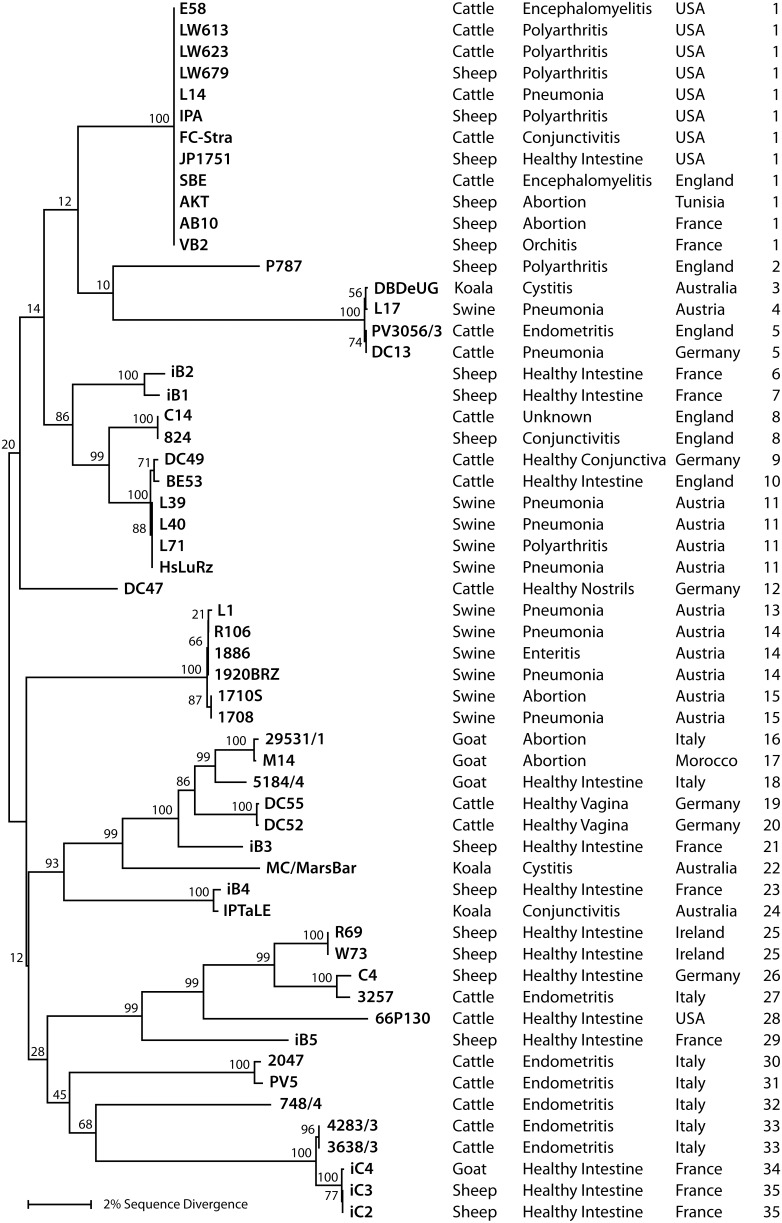

Figure 2. Unrooted neighbor-joining phylogram of ompA of 57 C. pecorum strains based on the nucleotide sequence alignment.

Percentages of branching patterns in bootstrap analyses of the dataset (10,000 replications) are indicated left to the branches. Host animal species, disease association, country of origin, and ompA phylogenetic rank are indicated in the columns to the right of the strain names.

To estimate the association of ompA genotype with disease, the deeply separated branches of the ompA phylogram in Figure 2 were stratified into 5 high- and 4 low-virulence clades. “High-virulence” clades contained 50% or more strains isolated from diseased animals (strains E58-VB2, P787-DC13, iB2-HsLuRz, L1-1708, 2047-748/4), while “low-virulence” clades contained less than 50% strains isolated from diseased animals (strains DC47, 29531/1-IPTaLE, R69-iB5, 4283/3-iC2). In sum, the high-virulence clades contained 30 high-virulence strains among a total of 35, while the low-virulence groups differed highly significantly and contained 7 high-virulence strains among a total of 21 (P = 0.0001; two-tailed Fisher Exact Test).

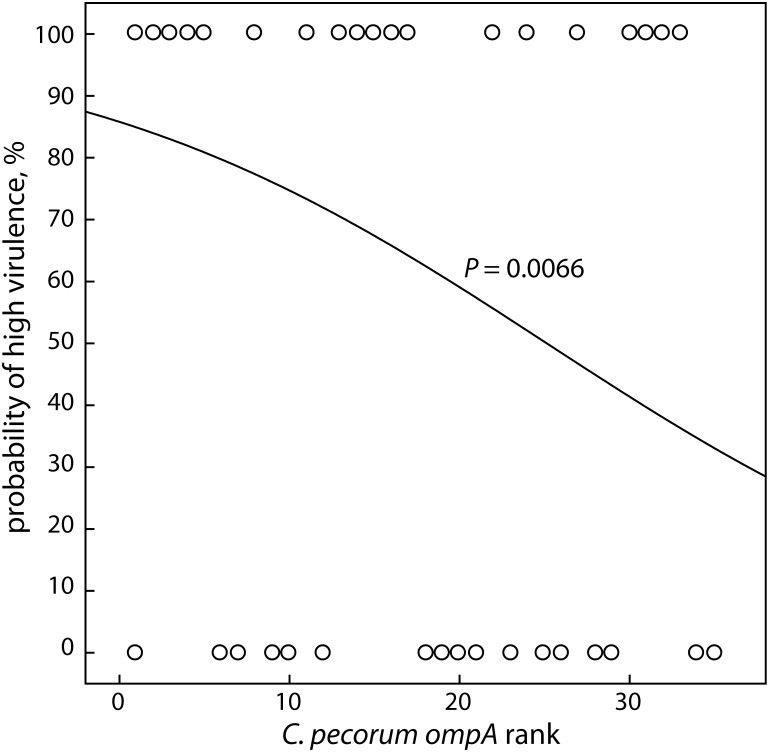

We also used non-stratified ompA phylogenetic rank data to evaluate the relation between ompA evolution and virulence by logistic regression. All strains with a unique ompA genotype received a unique phylogenetic rank number between 1 and 35, based on their position in the phylogram in Figure 2. C. pecorum strains isolated from diseased animals were scored as “high virulent” versus the strains isolated from healthy animals scored as “low virulent”. As evident in the highly significant regression plot (P = 0.0066; Figure 3), the probability of high virulence was high for low ompA rank, but dropped with increasing ompA rank. Thus, two analyses indicated that strain position on the ompA phylogenetic tree highly significantly correlates with virulence of C. pecorum isolates.

Figure 3. Relationship between virulence of C. pecorum strains and rank number in the ompA phylogram.

The probability of high virulence was determined by logistic regression analysis of the virulence of C. pecorum isolates scored by host disease association (0 = healthy; 100 = diseased), and ompA rank numbers of the isolates were regressed against virulence. The probability of high virulence decreases highly significantly with increasing ompA rank number.

Correlation of incA-coding tandem repeat sequence motifs with virulence

Next, we sought to quantitatively assess the relationship between the numbers of repetitions of sequence motifs in incA and the virulence of the C. pecorum strains. While amino acid APA/AGA motifs are dominant, addition of different motifs (APEVPA, APAVPA, APE, or APAPE) highly significantly associated with low virulence, i.e. 10 of 17 low-virulence strains possessed such sequence motifs, while 30 of 31 high-virulence strains did not (P<10−4; two-tailed Fisher Exact Test).

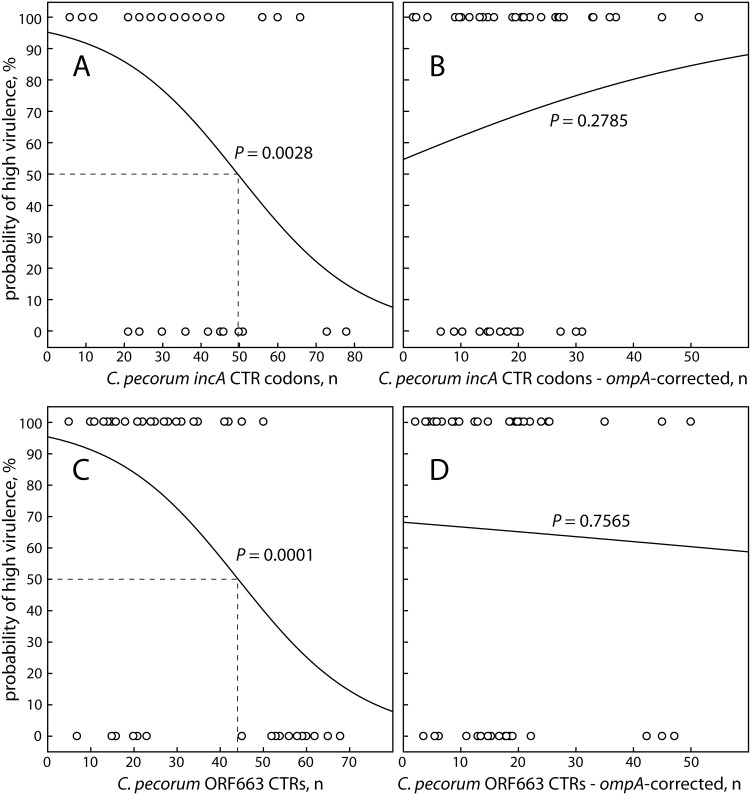

Similar to the ompA phylogenetic rank, we examined the correlation of the number of CTRs in incA with virulence by logistic regression. To account for the total amount of the different repeat motif insertions, we used the total number of amino acids encoded by these CTR codons. In logistic regression, high total CTR codon numbers highly significantly correlated with low virulence (P = 0.0028), with 50 codons representing a midpoint 50% probability of high virulence (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Relationship between virulence of C. pecorum strains and coding tandem repeats in incA and ORF663.

The probability of high virulence was determined by logistic regression analysis of the virulence of C. pecorum isolates, scored as in Figure 3, and continuous parameters for CTR numbers of the isolates were regressed against virulence. (A) the number of codons encoded by the CTRs in incA; (B) the number of codons encoded by the CTRs in incA corrected for the rank number of each isolate in the ompA phylogram. (C) The number of CTRs in ORF663; and (D) the number of CTRs in ORF663 corrected for the ompA rank number of each isolate. The highly significant correlation between CTRs and probability of high virulence in both incA and ORF663 is abolished by correction for ompA rank, indicating co-evolution of ompA, incA, and ORF663.

A fundamental question in this analysis is whether molecular evolution of the C. pecorum strains and incA CTR codon numbers is co-linear, and whether, therefore, the correlation between incA CTR codons and virulence was confounded by the phylogenetic position of the isolates. To account for C. pecorum evolution, we created a corrected incA CTR codon dataset that was controlled for the position of the isolates in the ompA phylogram. This was achieved by creating standardized phylogram rank data (mean = 0, SD = 1), adjusting these data to positive by adding 1+ the absolute minimum standardized rank number (results in 1 as the minimum adjusted standardized rank number), and dividing the number of incA CTR codon of each strain by the respective adjusted standardized ompA rank number. Using the ompA rank-corrected incA CTR codon data, we repeated the logistic regression analysis, but failed to obtain a significant correlation to virulence (P = 0.2785; Figure 4B). Thus, both incA and ompA evolution progress in a co-linear fashion, linking the number of incA CTR codons to the phylogenetic position of the C. pecorum ompA.

Correlation of coding tandem repeats in ORF663 with virulence

Similar to incA, we examined the correlation of the number of CTRs in ORF663 with virulence. The correlation of the number of CTRs in ORF663 with virulence was highly significant (P = 0.0001), again with low numbers of CTRs associating with high probability of high virulence, with 50% probability of high virulence at 43 repetitions (Figure 4C). Interestingly, there is a bimodal distribution of the CTR numbers in low-virulence strains, with 6 bovine strains isolated from healthy animals having less than 24 CTR repetitions, while all other isolates had 43 or more repetitions. When we tested for confounding by phylogenetic position using an ompA rank-corrected ORF663 CTR dataset, the correlation was lost (P = 0.7565; Figure 4D). Thus, analogous to incA, the number of CTRs in C. pecorum ORF663 and ompA evolution are closely linked.

Co-evolution of ompA, ORF663, and incA towards reduced virulence

As a final test for evolutionary linkage, we also tested for co-evolution of the CTR numbers in ORF663 and incA by creating an incA CTR codon number dataset that was corrected for ORF663 CTR numbers. Again, the ORF663 correction eliminated the correlation between incA CTR codons and virulence (P = 0.4234; data not shown), thus confirming incA and ORF663 co-evolution.

Collectively, these results suggested that the molecular evolution of C. pecorum progressed from ancestral strains with high virulence towards strains with low virulence, and that increased numbers of CTRs in inc A and ORF663, as well as recombination in ompA resulting in new C. pecorum serovars [26], were markers, if not mediators, of this progression towards low virulence. This hypothesis is testable with the present dataset since it implies that phylogenetic sequence divergence of ompA from the hypothetical ancestor inversely correlates with virulence of the extant C. pecorum strains. We assumed the root of the ompA phylogenetic tree at the connection to an outgroup composed of one ompA sequence of each of the eight remaining chlamydial species. This putative C. pecorum ancestor located to a set of short and weakly bootstrap-supported branches at the base of the phylogram (Figure 5). Association of virulence with evolutionary divergence of each strain from this ancestor was analyzed by logistic regression (Figure 5). While reduced probability of high virulence at long evolutionary distances was obvious from the placement of many strains isolated from healthy animals at the tips of long branches, this trend failed to reach significance (P = 0.0770; Figure 5).

Figure 5. Evolutionary distance from the putative ompA ancestor in correlation to virulence of C. pecorum strains.

A putative ancestral ompA was assumed at the connection of an outgroup, composed of one ompA sequence each of the 8 remaining chlamydial species, to the 57 C. pecorum ompA seqeunces (blue circle). This root is also consistent with an ancestor in the unrooted ompA neighbor-joining phylogram (Figure 2) at several poorly resolved and weakly bootstrap-supported branches that link the deep branches of the phylogenetic tree. Bootstrap support is indicated by numbers at branches, but not shown at terminal nodes of deep branches. Branch lengths are proportional to evolutionary ompA distance, with the bar indicating 2% sequence divergence (percent nucleotide substitutions). Low-virulence strains are indicated by green font, high-virulence strains by red font. Inset: The relationship between ompA evolutionary distance from the putative ancestor and the probability of high virulence of C. pecorum strains was determined by logistic regression analysis. Long evolutionary distance is correlated to low probability of high virulence, but fails to reach the P<0.05 significance threshold.

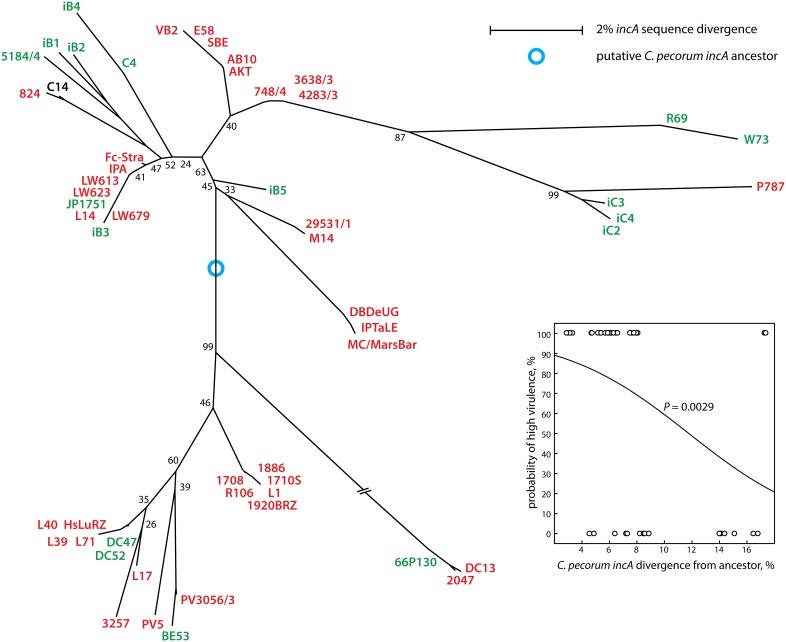

Next, we examined incA for evidence of linkage between virulence and distance from the evolutionary ancestor. Alignment of genes that contain different numbers of CTRs, such as incA, is notoriously difficult and very sensitive to the choice of alignment parameters. We optimized the alignment by minimizing average pairwise sequence distance, mainly by setting a high penalty for gap opening, and, less so, for gap extension. The resultant alignment (Figure 6; Figure S2) was used for phylogenetic reconstruction (Figure 7), and the putative ancestor was placed where an outgroup of incA homologs from the other eight chlamydial species connected to the phylogram of the highly conserved N-terminal fragment of C. pecorum incA (the hypervariable CTR region has no homolog). For incA, a highly significant inverse correlation between evolutionary divergence and probability of high virulence was found (P = 0.0029; Figure 7).

Figure 6. C. pecorum incA alignment.

The strain subset used in Figure 1 is shown. The complete incA is shown for all strains for which the sequence is available, demonstrating highly conserved 5′ (position 1-825 of strain E58) and 3′ ends of the gene (position 906-end of strain E58), interrupted by a highly variable region of coding tandem repeats. The alignment of the PCR fragment sequences available for all 57 strains, corresponding to positions 537 through the 3′ end of strain E58, was optimized for minimal sequence divergence and used for construction of the C. pecorum incA phylogenetic tree in Figure 7. The alignment of the resultant amino acid sequences of all 57 partial C. pecorum IncA proteins deduced from the nucleotide sequences is shown in Figure S2.

Figure 7. Evolutionary distance from the putative incA ancestor correlates to virulence of C. pecorum strains.

A neighbor-joining phylogram (not shown) was constructed of the conserved 5′ portion of incA of all available C. pecorum sequences, and an outgroup composed of one incA sequence of each of the 8 remaining chlamydial species. In this unrooted phylogram based on the sequence alignment of the 3′ incA fragment available for all 57 C. pecorum strains in this study, the putative ancestral incA was assumed at the connection of this outgroup (blue circle). Indicators of bootstrap support, branch lengths, and strain virulence correspond to Figure 5. Inset: The relationship between incA evolutionary distance from the putative ancestor and the probability of high virulence of C. pecorum strains was determined by logistic regression analysis. Long evolutionary distance is highly significantly correlated to low probability of high virulence.

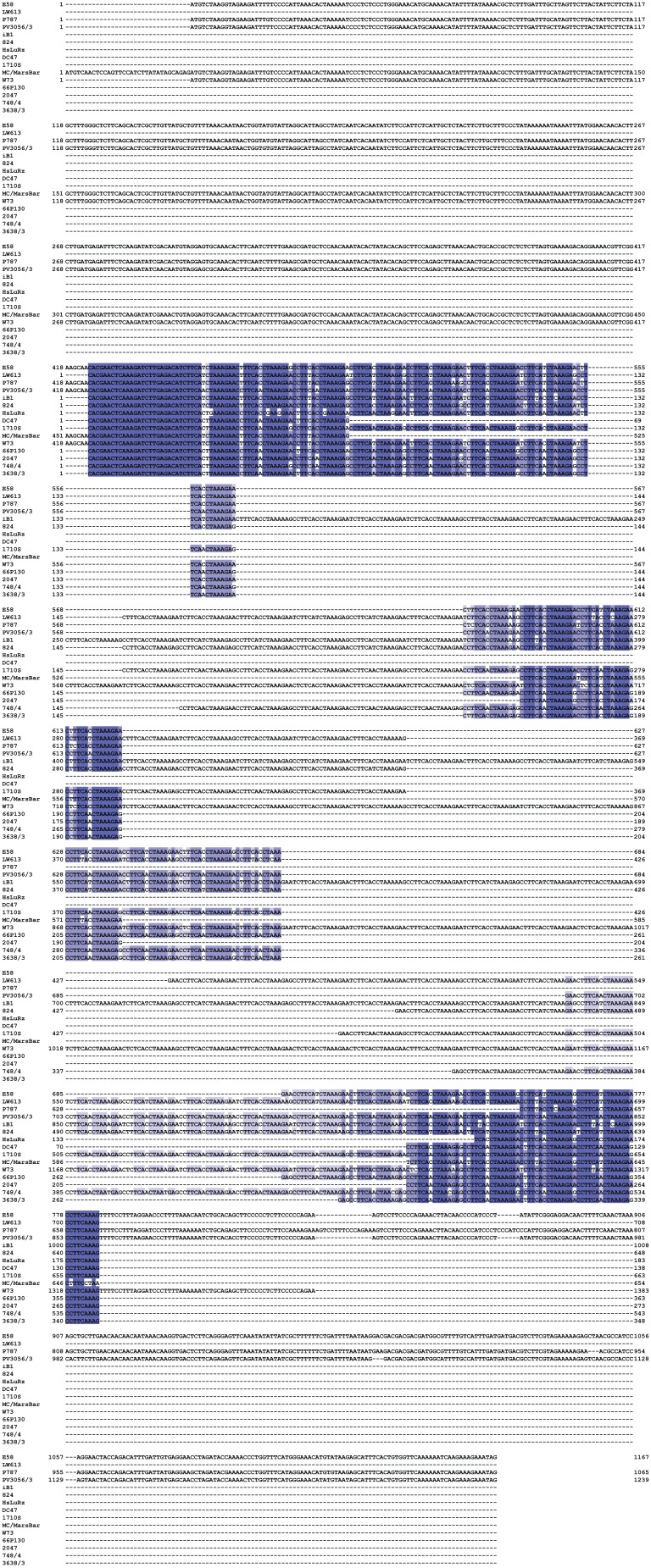

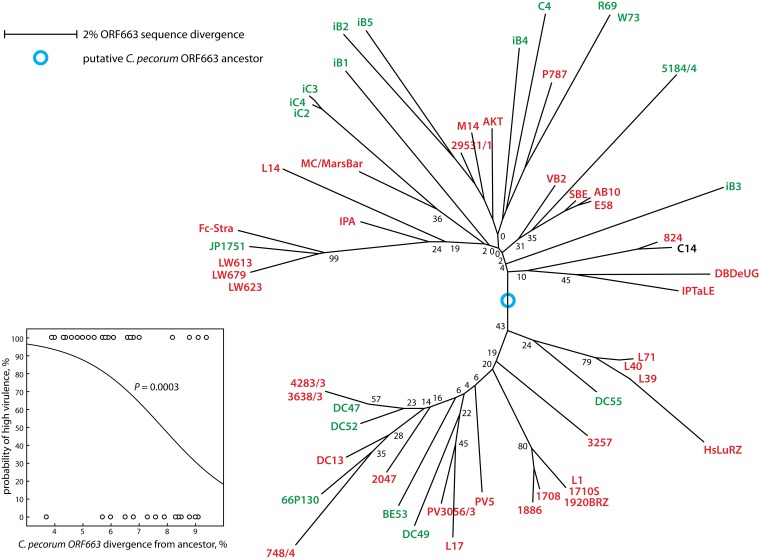

For ORF663, we used an approach similar to incA for alignment (Figure 8; Figure S3) and phylogenetic reconstruction (Figure 9). The relationship between long evolutionary distance from the putative ancestor and low virulence was even more pronounced for ORF663 (P = 0.0003; Figure 9). Thus, based on phylogenetic modeling, incA and ORF663 highly significantly, and ompA marginally so, co-evolve towards low virulence, irrespective of the branch of the phylogram, on which a specific strain is located.

Figure 8. C. pecorum ORF663 alignment.

The strain subset used in Figure 1 is shown. The complete ORF663 is shown for all strains for which the sequence is available, demonstrating a highly conserved 5′ portion (positions 1–493 of strain E58), followed by a highly variable region of coding tandem repeats containing a short conserved CTR fragment at position 748-786 of strain E58. The alignment of the PCR fragment sequences available for all 57 strains, corresponding to positions 424–786 of strain E58, was optimized for minimal sequence divergence and used for construction of the C. pecorum ORF663 phylogenetic tree in Figure 9. The alignment of the resultant amino acid sequences of all 57 full and partial C. pecorum IncA proteins deduced from the nucleotide sequences is shown in Figure S3.

Figure 9. Evolutionary distance from the putative ORF663 ancestor correlates to virulence of C. pecorum strains.

A neighbor-joining phylogram (not shown) was constructed of the conserved 5′ portion of ORF663 of all available C. pecorum sequences, and an outgroup composed of the ORF663 homologs found only in C. abortus, C. psittaci, C. caviae, and C. pneumoniae. In this unrooted phylogram based on the sequence alignment of the 3′ ORF663 fragment available for all 57 C. pecorum strains in this study, the putative ancestral ORF663 was assumed at the connection of this outgroup (blue circle). Indicators of bootstrap support, branch lengths, and strain virulence correspond to Figure 5. Inset: The relationship between ORF663 evolutionary distance from the putative ancestor and the probability of high virulence of C. pecorum strains was determined by logistic regression analysis. Long evolutionary distance is highly significantly correlated to low probability of high virulence.

Confirmation of C. pecorum gene co-evolution towards low virulence by mean pairwise sequence divergence

If the notion of C. pecorum evolution towards low virulence were correct, then a consequence would be that low-virulence strains have travelled a longer evolutionary path than high-virulence strains. This implies that the mean pairwise sequence divergence between low-virulence strains must be higher than that of high-virulence strains, irrespective of the distance from the ancestor, thus providing an easily testable hypothesis. The mean pairwise distances between ompA, incA, and ORF663 of C. pecorum strains isolated from healthy or diseased animals, as well as those of all 57 strains are listed in Table 2. In fact, for all three genes the mean sequence distance between low-virulence isolates from healthy animals is highly significantly by 2–3% higher than that of high-virulence isolates from diseased animals (Table 2). These data provide unambiguous confirmation of C. pecorum evolution towards low virulence.

Table 2. Mean pairwise sequence divergence between all 57 C. pecorum strains analyzed in this study, and between strains isolated from only healthy or from only diseased hosts.

| % Pairwise Divergence | Healthy* | Diseased | All |

| ompA | 13.23Ab (12.57–13.88) | 11.49C (11.10–11.87) | 12.49 (12.26–12.72) |

| incA | 12.39Ab (11.24–13.55) | 9.65C (9.16–10.14) | 10.85 (10.51–11.20) |

| ORF663 | 12.93AB (12.38–13.48) | 10.09C (9.81–10.36) | 11.13 (10.94–11.31) |

*Mean, 95% confidence interval.

Mean of Diseased highly significantly different at P≤10−5.

Mean of All significantly different at P<0.05.

Mean of All significantly different at P = 10−9.

Mean of All significantly different at P≤10−4.

Discussion

We undertook the present study with the primary aim to identify genetic markers that would allow us to unambiguously discriminate between highly virulent (“pathogenic”) and low-virulence or avirulent (“non-pathogenic”) C. pecorum strains that presumably would occupy different branches (clades) of the C. pecorum phylogeny. What our results tell us, though, is a different story, in essence that the main driver of reduction in virulence of C. pecorum is the distance a strain has traversed in its evolution from the primordial C. pecorum strain, and not the phylogenetic position in a specific clade. While it is clear that certain branches of the C. pecorum ompA phylogram harbor more highly virulent strains than others, it is uncertain if this is a genetically fixed property of this clade or has more to do with the short evolutionary distance from the ancestor.

The finding of the association of evolutionary distance with virulence is not surprising, given the endemic nature of C. pecorum infections in ruminants, swine, and koalas [3], [10], [27], [28], particularly in large herds [29]. Long-term coexistence of host and pathogen results in reduced virulence that is beneficial for the pathogen by maintaining a large host population. Effective adaptation to the host and the self-limiting nature of chlamydial intracellular multiplication may also explain the low number of isolates worldwide despite the ubiquity of C. pecorum infections. In addition, we assume that there is a bias towards isolation of C. pecorum from diseased animals rather than from healthy ones, because this is what diagnostic laboratories aim for, in particular given the high effort required for isolation of chlamydiae.

In consideration of the potential economic importance of these ubiquitous endemic bacteria [10], [14], [15], we collected a comprehensive set of DNAs of C. pecorum strains isolated worldwide from healthy as well as diseased mammalian livestock. Importantly, this study extended previous more limited analyses of ruminant C. pecorum strains to include unique sets of C. pecorum strains, isolated in Austria from diseased swine [2], [3] and in Australia from diseased koalas [30]. Following a previous investigation, we chose the ompA, incA and ORF663 loci as targets of our genetic analysis, which have now been identified by genome comparison as being among the most polymorphic genes of the C. pecorum genome, which is otherwise more than 99% conserved among the C. pecorum strains from which the whole genome is known [30]–[32]. Among these 8 strains, i.e. ruminant C. pecorum type strain E58, and strains P787, W73, PV3056/3, and IPA, and koala strains DBDeUG, MC/MarsBar, and IPTaLE, ompA is up to 16% divergent, and incA and ORF663 up to 8%. This remarkable polymorphism is presumably driven by immunoselection acting on the encoded proteins, all of which have been found immunodominant and eliciting high antibody responses ([3], [33], unpublished data).

The previously identified association of increasing numbers of CTRs in incA and ORF663 with reduced virulence [25] was highly significantly confirmed in this study. This finding is in agreement with a study that showed differences between environmental and clinical Legionella pneumophila strains in the repeat copy numbers of four genes [34]. Interestingly, six isolates from healthy animals in Germany, England, and the USA, had low numbers of ORF663 CTRs. This indicates that ORF663, as well as incA or ompA, cannot be used as the sole virulence marker. In ompA, specific sequence polymorphisms are not indicators of virulence, however in the context of the overall C. pecorum ompA phylogeny they are useful in quantifying distance from the root. As evident in Figure 4, the correlations of all three genes, ompA, incA, and ORF663 with virulence of the C. pecorum isolates are co-linear. Therefore, in combination these 3 genes may serve as probabilistic, but not absolute, markers of virulence.

For the practical use of such molecular markers, their genetic stability under non-selective culture conditions is important, and in fact they remain unchanged in laboratory maintenance of the isolates (data not shown), thus making these genes suitable for highly discriminatory epidemiological studies. At least one of these genes differed for two otherwise identical strains, except for 4 cases, namely LW613 and LW623, 3638/3 and 4283/3, L71 and L39, and E58 and SBE (Figure 2, Table 1), thus uniquely identifying 53 out of 57 C. pecorum strains.

The ability of C. pecorum to continuously evolve towards low virulence and generate successive allelic variants of incA, ORF663, and ompA may allow rapid adaptation to a host population and/or evasion of the host immune system. Changes in the repetitive coding regions (loss or gain), mediated by DNA replication error mechanisms, have been shown to cause phase variation in bacteria, which confer major defensive capabilities to the pathogen in order to escape from an aggressive host environment [35], [36]. Similarly, C. pecorum, in the process of inserting increasing numbers of CTRs in incA and ORF663 and recombining ompA, generates new serovars [26] and evolves towards lower virulence. One can speculate that this ompA evolution and many CTR insertions in incA and ORF663 change the immunological signature of a C. pecorum strain. Equally possible, however, is a scenario in which the immunosignature evolution of these genes is accompanied by point mutations in other genes that alter their function, and in that way mediate reduced virulence. Or, alternatively, CTR insertion, as occurs aside from incA and ORF663 in multiple other C. pecorum proteins such as polymorphic membrane proteins, cytotoxins, and phospholipase D-like proteins [32], may alter both function and immunosignature and mediate virulence reduction by both mechanisms. Therefore, the simultaneous evolutionary changes in ompA, incA, and ORF663 may or may not be functional correlates of virulence.

A point of criticism of the present analysis of C. pecorum virulence may be the fact that the differentiation is based on a single clinical examination of the animal from which the isolate was recovered (Figure 2). The diagnosis in that case may be tenuous in an epidemiological setting with ubiquitous endemic infections of C. pecorum [10]. However, the high number of 57 isolates included in this study obtained by numerous investigators over a period of 50 years should alleviate concerns about diagnostic accuracy. If the clinical diagnoses had been widely aberrant, it is very unlikely that we would have been able to demonstrate co-linear correlation with virulence of three independent genetic markers in this study. In addition, Storz et al. [37] have experimentally confirmed this genetic differentiation in virulence long ago by experimental oral inoculation of calves, the original host, with C. pecorum isolates LW613 or 66P130. Highly virulent strain LW613 caused severe hemorrhagic diarrhea and polyarthritis with predominantly lethal outcome. In contrast, strain 66P130, isolated from feces of a healthy calf, caused only transient mild diarrhea. Thus, experimental inoculation of the original host may produce severe disease only with highly virulent isolates, while such isolates may also be detected in asymptomatic natural infections [15]. These asymptomatic infections, by high- as well as low-virulence C. pecorum strains, reduce growth rates in calves by eliciting a status of systemic inflammation [15]. Unraveling the contribution of low- and high-virulence C. pecorum strains to performance reduction in livestock will be of great scientific as well as economic interest.

Methods

Chlamydial isolates

Thirty two C. pecorum strains were newly analyzed in this study, while the remaining 25 isolates had been examined before [24], [25] or published recently [30], [32]. The strains were propagated in the yolk sac of chicken embryos and stored at −70°C as previously described [38]. All isolates were obtained from routine diagnostic specimens in veterinary diagnostics laboratories in Austria (11 isolates), England (1 isolate), Germany (6 isolates), Italy (8 isolates), the USA (6 isolates). The 17 strains from Austria and the USA were isolated between 1965 and 1970, when ethical regulations regarding animal specimens did not exist. The remaining isolates from England, Germany, and Italy were obtained between 1993 and 2006 in governmental veterinary diagnostic laboratories that strictly operated under ethics rules established in the respective countries. None of the specimens obtained caused suffering to the animals in addition to the suffering caused by the natural chlamydial infection.

PCR conditions and sequencing

PCR was performed according to the GoTaq Flexi DNA Polymerase (Promega, Charbonnieres, France) protocol in a final volume of 50 µL, and consisted of DNA denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of amplification in a UNO II thermoblock (Biometra, Göttingen, Germany). Each cycle consisted of a denaturation step at 94°C for 30 sec, an annealing step at 55°C (for ompA and ORF663) or at 63°C (for incA) for 45 sec, an extension step at 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final chain elongation at 72°C for 7 min. The primer pairs used in this study except for forward incA primer b15-F (5′-CAAGAACAGTTGCGTCCTG-3′) have been described before [25]. The PCR products were sequenced by automated sequencing (Genome Express, Meylan, France). The complete DNA sequences of ompA genes and partial sequences of incA and ORF663 genes were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers listed in Table 1.

Sequence alignment and analysis

The number of repetitions of 15-mer CTR in ORF663 was identified using Tandem repeat finder software [39]. Deduced amino acid sequences were first aligned in the freeware MEGA6 [40] by use of the MUSCLE algorithm that considered for the nucleotide alignment all codon positions according to the Blosum 62 AA substitution matrix. Two obvious sequencing errors in the IPTaLE incA between positions 354–367 were manually corrected. Evolutionary distances were computed in MEGA6 in a maximum composite likelihood model as the number of base substitutions per site. Alignments were optimized by varying alignment parameters, in particular gap opening and extension penalties. A gap opening penalty of −5 and extension penalty of −1 resulted in minimum average pairwise sequence distances for all 3 genes, and was used to construct sequence alignments. Publication quality alignments were produced in freeware toolkit Jalview [41]. The evolutionary history was inferred by phylogenetic reconstruction by the neighbor-joining method in the freeware MEGA6 [40], with gaps removed from calculation by pairwise deletion.

Statistical analysis

Virulence association of ompA phylogram clades of and novel incA repeat sequences was analyzed by two-tailed Fisher Exact test. Correlation of C. pecorum strain virulence with ompA rank, incA CTR codon numbers, CTRs in ORF663, and the ompA, incA, and ORF663 nucleotide sequence divergence from the respective ancestral C. pecorum gene was determined by logistic regression analysis. Differences in mean pairwise sequence divergence were analysed by Student’s t-test. All statistical analyses were performed by use of the Statistica 7.1 software package (Statsoft, Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA).

Supporting Information

C. pecorum OmpA protein alignment. Full-length peptide sequences of all 57 analyzed C. pecorum strains are shown. The background colors follow the Zappo color scheme for visualization of multi-peptide alignments [41], and correspond to alignment quality determined by amino acid identities and physicochemical similarities according to the Blosum 62 matrix (Pink = aliphatic/hydrophobic aa I, L, V, A, M; orange = aromatic aa F, W, Y; blue = positive aa K, R, H; red = negative aa D, E; green = hydrophilic aa S, T, N, Q; purple = conformationally special aa P, G; yellow = C). Four variable domains, distinguished by the gap insertions in the alignment, are interspersed between 5 highly conserved domains of the OmpA protein.

(TIF)

C. pecorum IncA protein alignment. IncA peptide sequences of all 57 analyzed C. pecorum strains are shown. The complete IncA protein was used for alignment, and all available full-length sequences are shown in addition to the sequences encoded by the PCR fragment available for all strains. Amino acids 180 through C-terminal amino acid 326 of strain E58 correspond to the PCR fragment sequence used for phylogenetic reconstruction. Background Zappo colors correspond to alignment quality according to the Blosum 62 matrix. A highly conserved N-terminal region of approximately 275 amino acids is followed by a hypervariable region of inserted coding tandem repeats followed by a short conserved C-terminus of the IncA protein.

(TIF)

C. pecorum ORF663 protein alignment. ORF663 peptide sequences of all 57 analyzed C. pecorum strains are shown. The complete ORF5663 protein was used for alignment, and all available full-length sequences are shown in addition to the sequences encoded by the PCR fragment available for all strains. Amino acids 142-262 of strain E58 correspond to the PCR fragment sequence used for phylogenetic reconstruction. Background Zappo colors correspond to alignment quality according to the Blosum 62 matrix. A highly conserved N-terminal region of 154 or 165 amino acids is followed by a hypervariable region of inserted coding tandem repeats followed by short or long variants of a conserved C-terminus of the ORF663 protein.

(TIF)

Funding Statement

The study was funded by the French Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, and current funding by Auburn University. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Kuo CC, Stephens RS, Bavoil PM, Kaltenboeck B (2011) Genus I. Chlamydia Jones, Rake and Stearns 1945, 55AL. In: Krieg NR, Staley JT, Brown DR, Hedlund BP, Paster BJ, et al. editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. New York. Bergey’s Manual Trust. 846–865. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaltenboeck B, Kousoulas KG, Storz J (1993) Structures of and allelic diversity and relationships among the major outer membrane protein (ompA) genes of the four chlamydial species. J Bacteriol 175: 487–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kaltenboeck B, Storz J (1992) Biological properties and genetic analysis of the ompA locus in chlamydiae isolated from swine. Am J Vet Res 53: 1482–1487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Greco G, Corrente M, Buonavoglia D, Campanile G, Di Palo R, et al. (2008) Epizootic abortion related to infections by Chlamydophila abortus and Chlamydophila pecorum in water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis). Theriogenology 69: 1061–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jackson M, White N, Giffard P, Timms P (1999) Epizootiology of Chlamydia infections in two free-range koala populations. Vet Microbiol 65: 255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Warren K, Swan R, Bodetti T, Friend T, Hill S, et al. (2005) Ocular chlamydiales infections of western barred bandicoots (Perameles bougainville) in Western Australia. J Zoo Wildl Med 36: 100–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Di Francesco A, Baldelli R, Donati M, Cotti C, Bassi P, et al. (2013) Evidence for Chlamydiaceae and Parachlamydiaceae in a wild boar (Sus scrofa) population in Italy. Vet Ital 49: 119–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lenzko H, Moog U, Henning K, Lederbach R, Diller R, et al. (2011) High frequency of chlamydial co-infections in clinically healthy sheep flocks. BMC Vet Res 7: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Godin AC, Björkman C, Englund S, Johansson KE, Niskanen R, et al. (2008) Investigation of Chlamydophila spp. in dairy cows with reproductive disorders. Acta Vet Scand 50: 39–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reinhold P, Sachse K, Kaltenboeck B (2011) Chlamydiaceae in cattle: commensals, trigger organism, or pathogens? Vet J 189: 257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mohamad KY, Rodolakis A (2010) Recent advances in the understanding of Chlamydophila pecorum infections, sixteen years after it was named as the fourth species of the Chlamydiaceae family. Vet Res 41: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kauffold J, Melzer F, Henning K, Schulze K, Leiding C, et al. (2006) Prevalence of chlamydiae in boars and semen used for artificial insemination. Theriogenology 65: 1750–1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wan C, Loader J, Hanger J, Beagley K, Timms P, et al. (2011) Using quantitative polymerase chain reaction to correlate Chlamydia pecorum infectious load with ocular, urinary and reproductive tract disease in the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). Aust Vet J 89: 409–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reinhold P, Jaeger J, Liebler-Tenorio E, Berndt A, Bachmann R, et al. (2008) Impact of latent infections with Chlamydophila species in young cattle. Vet J 175: 202–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Poudel A, Elsasser TH, Rahman KhS, Chowdhury EU, Kaltenboeck B (2012) Asymptomatic endemic Chlamydia pecorum infections reduce growth rates in calves by up to 48 percent. PLoS One 7: e44961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sachse K, Laroucau K, Vorimore F, Magnino S, Feige J, et al. (2009) DNA microarray-based genotyping of Chlamydophila psittaci strains from culture and clinical samples. Vet Microbiol 135: 22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pannekoek Y, Morelli G, Kusecek B, Morre SA, Ossewaarde JM, et al. (2008) Multi locus sequence typing of Chlamydiales: clonal groupings within the obligate intracellular bacteria Chlamydia trachomatis . BMC Microbiol 8: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Laroucau K, Thierry S, Vorimore F, Blanco K, Kaleta E, et al. (2008) High resolution typing of Chlamydophila psittaci by multilocus VNTR analysis (MLVA). Infect Genet Evol 8: 171–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van Duynhoven YT, Ossewaarde JM, Derksen-Nawrocki RP, van der Meijden WI, van de Laar MJ (1998) Chlamydia trachomatis genotypes: correlation with clinical manifestations of infection and patient’s characteristics. Clin Infect Dis 26: 314–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gao X, Chen XS, Yin YP, Zhong MY, Shi MQ, et al. (2007) Distribution study of Chlamydia trachomatis serovars among high-risk women in China performed using PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism genotyping. J Clin Microbiol 45: 1185–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vanrompay D, Ducatelle R, Haesebrouck F (1995) Chlamydia psittaci infections: a review with emphasis on avian chlamydiosis. Vet Microbiol 45: 93–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Denamur E, Sayada C, Souriau A, Orfila J, Rodolakis A, et al. (1991) Restriction pattern of the major outer-membrane protein gene provides evidence for a homogeneous invasive group among ruminant isolates of Chlamydia psittaci . J Gen Microbiol 137: 2525–2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Salinas J, Souriau A, De Sa C, Andersen AA, Rodolakis A (1996) Serotype 2-specific antigens from ruminant strains of Chlamydia pecorum detected by monoclonal antibodies. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 19: 155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yousef Mohamad K, Rekiki A, Myers G, Bavoil PM, Rodolakis A (2008) Identification and characterisation of coding tandem repeat variants in incA gene of Chlamydophila pecorum . Vet Res 39: 56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mohamad KY, Roche SM, Myers G, Bavoil PM, Laroucau K, et al. (2008) Preliminary phylogenetic identification of virulent Chlamydophila pecorum strains. Infect Genet Evol 8: 764–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kaltenboeck B, Heinen E, Schneider R, Wittenbrink MM, Schmeer N (2009) OmpA and antigenic diversity of bovine Chlamydophila pecorum strains. Vet Microbiol 135: 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marsh J, Kollipara A, Timms P, Polkinghorne A (2011) Novel molecular markers of Chlamydia pecorum genetic diversity in the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). BMC Microbiol 11: 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jelocnik M, Frentiu FD, Timms P, Polkinghorne A (2013) Multilocus Sequence Analysis Provides Insights into Molecular Epidemiology of Chlamydia pecorum Infections in Australian Sheep, Cattle, and Koalas. J Clin Microbiol 51: 2625–2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jee JB, DeGraves FJ, Kim TY, Kaltenboeck B (2004) High Prevalence of Natural Chlamydophila Species Infection in Calves. J Clin Microbiol. 42: 5664–5672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polkinghorne A (2014) Personal communication.

- 31. Mojica S, Huot Creasy H, Daugherty S, Read TD, Kim T, et al. (2011) Genome sequence of the obligate intracellular animal pathogen Chlamydia pecorum E58. J Bacteriol 193: 3690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sait M, Livingstone M, Clark EM, Wheelhouse N, Spalding L, et al. (2014) Genome sequencing and comparative analysis of three Chlamydia pecorum strains associated with different pathogenic outcomes. BMC Genomics 15: 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mohamad KY, Rekiki A, Berri M, Rodolakis A (2010) Recombinant 35-kDa inclusion membrane protein IncA as a candidate antigen for serodiagnosis of Chlamydophila pecorum . Vet Microbiol 143: 424–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Coil DA, Vandersmissen L, Ginevra C, Jarraud S, Lammertyn E, et al. (2008) Intragenic tandem repeat variation between Legionella pneumophila strains. BMC Microbiol 8: 218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hood DW, Deadman ME, Jennings MP, Bisercic M, Fleischmann RD, et al. (1996) DNA repeats identify novel virulence genes in Haemophilus influenzae . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93: 11121–11125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sachse K, Helbig JH, Lysnyansky I, Grajetzki C, Müller W, et al. (2000) Epitope mapping of immunogenic and adhesive structures in repetitive domains of Mycoplasma bovis variable surface lipoproteins. Infect Immun 68: 680–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Storz J, Collier JR, Eugster AK, Altera KP (1971) Intestinal bacterial changes in Chlamydia-induced primary enteritis of newborn calves. Ann NY Acad Sci 176: 162–175. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rodolakis A (1976) Abortive infection of mice inoculated intraperitoneally with Chlamydia ovis . Ann Rech Vet 7: 195–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Benson G (1999) Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Research 27: 573–580 Available: http://tandem.bu.edu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S (2013) MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol 30: 2725–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DMA, Clamp M, Barton GJ (2009) Jalview Version 2 - a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 25: 1189–1191 doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Norton WL, Storz J (1967) Observations on sheep with polyarthritis produced by an agent of the psittacosis-lymphogranuloma venereum-trachoma group. Arthritis Rheum 10: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rodolakis A, Bernard F, Lantier F (1989) Mouse models for evaluation of virulence of Chlamydia psittaci isolated from ruminants. Res Vet Sci 46: 34–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

C. pecorum OmpA protein alignment. Full-length peptide sequences of all 57 analyzed C. pecorum strains are shown. The background colors follow the Zappo color scheme for visualization of multi-peptide alignments [41], and correspond to alignment quality determined by amino acid identities and physicochemical similarities according to the Blosum 62 matrix (Pink = aliphatic/hydrophobic aa I, L, V, A, M; orange = aromatic aa F, W, Y; blue = positive aa K, R, H; red = negative aa D, E; green = hydrophilic aa S, T, N, Q; purple = conformationally special aa P, G; yellow = C). Four variable domains, distinguished by the gap insertions in the alignment, are interspersed between 5 highly conserved domains of the OmpA protein.

(TIF)

C. pecorum IncA protein alignment. IncA peptide sequences of all 57 analyzed C. pecorum strains are shown. The complete IncA protein was used for alignment, and all available full-length sequences are shown in addition to the sequences encoded by the PCR fragment available for all strains. Amino acids 180 through C-terminal amino acid 326 of strain E58 correspond to the PCR fragment sequence used for phylogenetic reconstruction. Background Zappo colors correspond to alignment quality according to the Blosum 62 matrix. A highly conserved N-terminal region of approximately 275 amino acids is followed by a hypervariable region of inserted coding tandem repeats followed by a short conserved C-terminus of the IncA protein.

(TIF)

C. pecorum ORF663 protein alignment. ORF663 peptide sequences of all 57 analyzed C. pecorum strains are shown. The complete ORF5663 protein was used for alignment, and all available full-length sequences are shown in addition to the sequences encoded by the PCR fragment available for all strains. Amino acids 142-262 of strain E58 correspond to the PCR fragment sequence used for phylogenetic reconstruction. Background Zappo colors correspond to alignment quality according to the Blosum 62 matrix. A highly conserved N-terminal region of 154 or 165 amino acids is followed by a hypervariable region of inserted coding tandem repeats followed by short or long variants of a conserved C-terminus of the ORF663 protein.

(TIF)