Abstract

Importance

Older adults are often excluded from clinical trials. The benefit of preventive interventions tested in younger trial populations may be reduced when applied to older adults in the clinical setting if they are less likely to survive long enough to experience those outcomes targeted by the intervention.

Objective

To extrapolate a treatment effect similar to those reported in major randomized controlled clinical trials of ACE inhibitors and ARBs for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) prevention to a real-world population of older patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Design and Setting

Simulation study in a retrospective cohort; Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).

Participants

371,470 VA patients aged ≥ 70 years with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Main outcomes and measures: Among members of this cohort, we evaluated the expected effect of a 30% reduction in relative risk on the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one case of ESRD over a three year period. These parameters were selected to mimic the treatment effect achieved in major trials of ACE inhibitors and ARBs for ESRD prevention which have reported relative risk reductions of between 23% and 56% over observation periods of 2.6 to 3.4 years yielding NNTs to prevent one case of ESRD of between 9 and 25.

Results

The NNT to prevent one case of ESRD among members of this cohort ranged from 16 in patients with the highest baseline risk (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 15–29 ml/min/1.73 m2 and ≥ 2+ proteinuria) to 2,500 for those with the lowest baseline risk (eGFR 45–59 ml/min/1.73 m2 and negative/trace proteinuria and eGFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and 1+proteinuria). Most patients belonged to groups with an NNT >100. This was true even when the exposure time was extended over 10 years and in all sensitivity analyses.

Conclusion and relevance

Differences in baseline risk and life expectancy between trial subjects and real-world populations of older adults with CKD may reduce the marginal benefit to individual patients of interventions to prevent ESRD.

Keywords: elderly, chronic kidney disease, end-stage renal disease, prevention, ACE inhibitor, ARB, number needed to treat

Elderly patients are often underrepresented in clinical trials (1–3). Extrapolating the results of trials conducted in younger adults to older patients in the clinical setting can often be challenging. Differences in underlying disease processes, in the presence and severity of co-existing comorbid conditions, and in the clinical context in which interventions are deployed may modify the efficacy, tolerability and relevance of interventions tested in clinical trials when applied to older adults in real-world clinical settings (4–10).

Many interventions recommended in older adults are intended to prevent or delay the onset of non-fatal health outcomes. For these interventions, differences in life expectancy and baseline risk between trial populations and real-world populations of older adults may further modify the expected benefit (11–13). Patients whose life expectancy is more limited or whose baseline risk for the outcome of interest is lower than for the trial population may have less opportunity to benefit from preventive interventions with known efficacy. Thus, in considering treatments intended to lower the risk of non-fatal health outcomes, older patients and their providers must weigh available information on efficacy in the context of their likelihood of experiencing the relevant outcome during their remaining life time and their own treatment priorities (11–14).

To illustrate the importance of interpreting treatment effects from clinical trials in the context of real-world risk information, we conducted a simulation study in which we applied a relative risk reduction similar to that achieved in major randomized controlled trials of ACE inhibitors and ARBs for the prevention of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) to a real-world cohort of elderly patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). These agents have been shown to slow progression to ESRD in clinical trials that were conducted in younger populations at high risk for ESRD (15–17). However, the benefit of these agents in reducing the risk of ESRD in an individual patient is conditional on that patient’s likelihood of surviving long enough to develop ESRD, a quantity that may vary as a function of both life expectancy and baseline risk of ESRD. We therefore hypothesized that the marginal benefit to individual patients of a treatment effect similar to that achieved in major trials of ACE inhibitors and ARBs would differ when applied to a real-world cohort of older adults with CKD.

Methods

Analytic Overview

The treatment effect and exposure time were selected after reviewing the design of and relative risk reductions achieved in trials included in two recent systematic reviews of ESRD prevention (15, 16). Specifically, we considered the subset of four trials that enrolled at least 350 participants and found a lower incidence of ESRD (defined as dialysis or transplant) among participants treated with an ACE inhibitor or ARB compared with participants in the control arm (18–21) (Table 1). None of these trials enrolled adults older than 70, two of the four required that participants have diabetes, three required that participants have proteinuria, and all enrolled participants with renal insufficiency. Mortality rates among members of the control groups ranged from 0 to 21% across trials. Based on the duration (2.6 to 3.4 years) and relative risk reductions (23% to 56%) achieved in these trials, we selected a 30% reduction in the relative risk of ESRD and an observation period of three years.

Table 1.

Entry criteria and outcomes of major trials reporting a protective effect of ACE inhibitors or ARBs on progression to ESRD

| Author, Publication year |

N | Intervention | FU (y) |

Entry criteria | Mortality, % | ESRD, % | ESRD RRR, % |

ESRD ARR, % |

ESRD NNT |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) |

DM | Renal function |

Proteinuria | Control group |

Rx group |

Control group |

Rx group |

|||||||

| Brenner 2001 (18) |

1513 | Losartan vs. placebo |

3.4 | 31– 70 |

yes | Scr 1.3–3 mg/dL |

ACR >300 mg/g |

20.3 | 21 | 25.5 | 19.6 | 23 | 5.9 | 17 |

| Lewis 1993 (19) |

409 | Captopril vs. placebo |

3 | 18– 49 |

yes | Scr ≤ 2.5 mg/dL |

Urine protein ≥ 500 mg/g |

6.9 | 3.9 | 15.4 | 9.7 | 37.0 | 5.7 | 18 |

| Ruggenenti 1999 (20) |

352 | Ramipril vs. placebo |

2.6 | 18– 70 |

IDDM excluded |

CrCl 20–70 ml/min |

Stratum 1: urine protein ≥ 1 g/d and <3 g/d |

0 | 1.0 | 20.7 | 9.1 | 56.0 | 11.6 | 9 |

| Agodoa 2001 (21) |

1094 | Ramipril vs. amlodopine |

3 | 18– 70 |

No | GFR 20–65 ml/min/1.73 m2 |

urinary protein to creatinine ratio ≤ 2.5 mg/g |

6.0 | 4.1 | 14.8 | 10.8 | 27.0 | 4 | 25 |

ESRD was defined by trials as initiation of dialysis or receipt of a kidney transplant. For each trial, we calculated the relative risk reduction, absolute risk reduction and NNT based on the reported percentage of participants in the ACE inhibitor or ARB vs. control arm who developed ESRD during the trial. Abbreviations: N number of trial participants; FU mean follow-up time; y years; RX group intervention group; ESRD end-stage renal disease; RRR relative risk reduction; ARR absolute risk reduction, NNT number needed to treat to prevent one case of ESRD calculated as the reciprocal of the absolute risk reduction; DM diabetes mellitus; IDDM insulin dependent diabetes mellitus; Scr serum creatinine; CrCl creatinine clearance; GFR glomerular filtration rate.

We assumed that the same reduction in relative risk would apply to a real-world population of older patients with CKD. We used information on observed survival and incident ESRD among members of this cohort to determine the probability that a patient would develop ESRD within three years of cohort entry. We then estimated the absolute reduction in risk of ESRD that would occur if patients experienced a 30% reduction in the relative risk of ESRD over this time frame. The estimated number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one case of ESRD was then calculated as the reciprocal of the expected absolute risk reduction. To account for the impact of mortality during follow-up on the NNT and to parallel the method for calculation of the NNT in trials, rates of ESRD during the three year observation period were calculated among the denominator of patients who entered the cohort, regardless of whether they died during follow-up. These estimates are presented for groups defined by level of eGFR and proteinuria because both are strongly associated with survival and risk of ESRD and because trials selected for patients with relatively high levels of proteinuria and low levels of renal function who were at higher risk for ESRD.

We used the same approach to evaluate the effect of a longer exposure to the treatment effect over ten years. For members of this cohort who died within this time frame, the ten year NNT reported here would represent an optimistic estimate of the NNT had the treatment been continued over their remaining lifetime. Our analyses were thus designed to account for two reasons a patient’s absolute risk for ESRD might differ from that observed in the trials. First, they may have a lower baseline risk of developing ESRD. Second, they may be less likely to live long enough to progress to ESRD.

We estimated the NNT to prevent one case of ESRD within three years of cohort entry in the following sensitivity analyses. First, because some trials were conducted only among patients with diabetes, we restricted the analysis to patients with a diagnostic code for diabetes during the year before cohort entry. Second, because some cohort members were already receiving ACE inhibitors or ARBs at cohort entry, we repeated our analyses after excluding these patients. Third, to account for possible age differences in uptake of renal replacement therapy, we expanded the definition of ESRD to include patients who died during follow-up and whose most recent eGFR before death was <15 ml/min/1.73 m2. Finally, we repeated the primary analysis using relative risk reductions of 23% and 56%, respectively to reflect the full range or treatment effects reported in individual trials.

Patients and data sources

We identified 790,342 patients aged 70 years and older who were not receiving chronic dialysis, had not received a kidney transplant and had at least one outpatient serum creatinine measurement at a VA medical center between October 1, 2000 to September 30, 2001. The date of the first serum creatinine measurement during this time period was taken as the date of cohort entry. For patients with urine protein dipstick measurements, we used the most recently available prior to serum creatinine measurement. All analyses were conducted among the subset of patients with stages I- IV CKD defined as having either an eGFR between 15 and 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 or ≥1+ proteinuria on dipstick (n=371,470). Serum creatinine measurements were obtained from the VA Decision Support System Laboratory Results file (that records the results of serum creatinine tests obtained at VA medical centers) and urine protein dipstick results were obtained from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse. Information on age was ascertained from the VA Vital Status file. Information on race was ascertained from both Medicare and VA sources, with preference for Medicare race data when available. Patients with diabetes were identified using inpatient and outpatient diagnostic code search of both VA and Medicare sources. Prescription of ACE inhibitors and ARBs at the time of cohort entry was ascertained using the DSS Pharmacy files. Information on date of death was obtained from the VA Vital Status File (a comprehensive source of death data for Veterans) which was available through July 23, 2013 (22). ESRD defined as initiation of chronic dialysis or receipt of a kidney transplant was ascertained by linkage to the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), a national registry for ESRD. Follow-up for ESRD was available through September 30, 2011. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the VA Puget Sound Healthcare System.

Results

The mean age of cohort patients was 77.8 (± 4.6) years, 2% were women, 9.2% were African American, 47.1% had a diagnostic code for diabetes (n=174,879), and 37.9% had an active prescription for an ACE inhibitor or ARB at the time of cohort entry (n=140,647). Mean eGFR was 48.0 (±11.7) ml/min/1.73 m2. Most patients had moderate reductions in eGFR in the 30–59 ml/min/1.73 m2 range and negative, trace or unmeasured proteinuria (Table 2).

Table 2.

Percentage of patients who developed ESRD within three years of cohort entry and corresponding absolute risk reduction

| Level of eGFR (ml/min/1.732) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of proteinuria | ≥ 60 (n=17,089) | 45–59 (n=223,119) | 30–44 (n=103,671) | 15–29 (n=27,591) | ||||||||

| ESRD, % | ARR, % |

NNT | ESRD, % |

ARR, % |

NNT | ESRD, % | ARR, % |

NNT | ESRD, % | ARR, % |

NNT | |

| Negative/trace (n=137,175) | NA | NA | NA | 0.13 | 0.04 | 2500 | 0.49 | 0.15 | 667 | 4.43 | 1.33 | 75 |

| 1+ protein (n=26,655) | 0.13 | 0.04 | 2500 | 0.31 | 0.09 | 1111 | 0.86 | 0.26 | 385 | 9.55 | 2.87 | 35 |

| ≥ 2+ protein (n=22,536) | 0.25 | 0.08 | 1250 | 0.98 | 0.29 | 345 | 3.58 | 1.07 | 94 | 21.17 | 6.35 | 16 |

| Unmeasured (n=185,104) | NA | NA | NA | 0.19 | 0.06 | 1667 | 0.83 | 0.25 | 400 | 8.47 | 2.54 | 39 |

Abbreviations: NA not applicable as not included in cohort; ESRD, percent of patients who initiated chronic dialysis or received a kidney transplant during trial period; ARR absolute risk reduction associated with a 30% reduction in relative risk; NNT number needed to treat to prevent one case of ESRD during follow-up; eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate. NNTs are rounded to the closest integer.

Overall, 1.1% of cohort members reached ESRD within three years of cohort entry, ranging from 0.13% of those in the lowest risk groups (those with an eGFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and 1+ proteinuria and those with an eGFR 45–59 ml/min/1.73 m2 with negative/trace proteinuria) to 21.17% for those in the highest risk group (eGFR 15–29 ml/min/1.73 m2 and ≥ 2+ proteinuria) (Table 2). NNTs for a 30% reduction in the relative risk of ESRD over the three year exposure period ranged from 16 for the highest risk group to 2,500 for the lowest risk group. Overall, 91 % of cohort members belonged to a group for which the NNT exceeded 100.

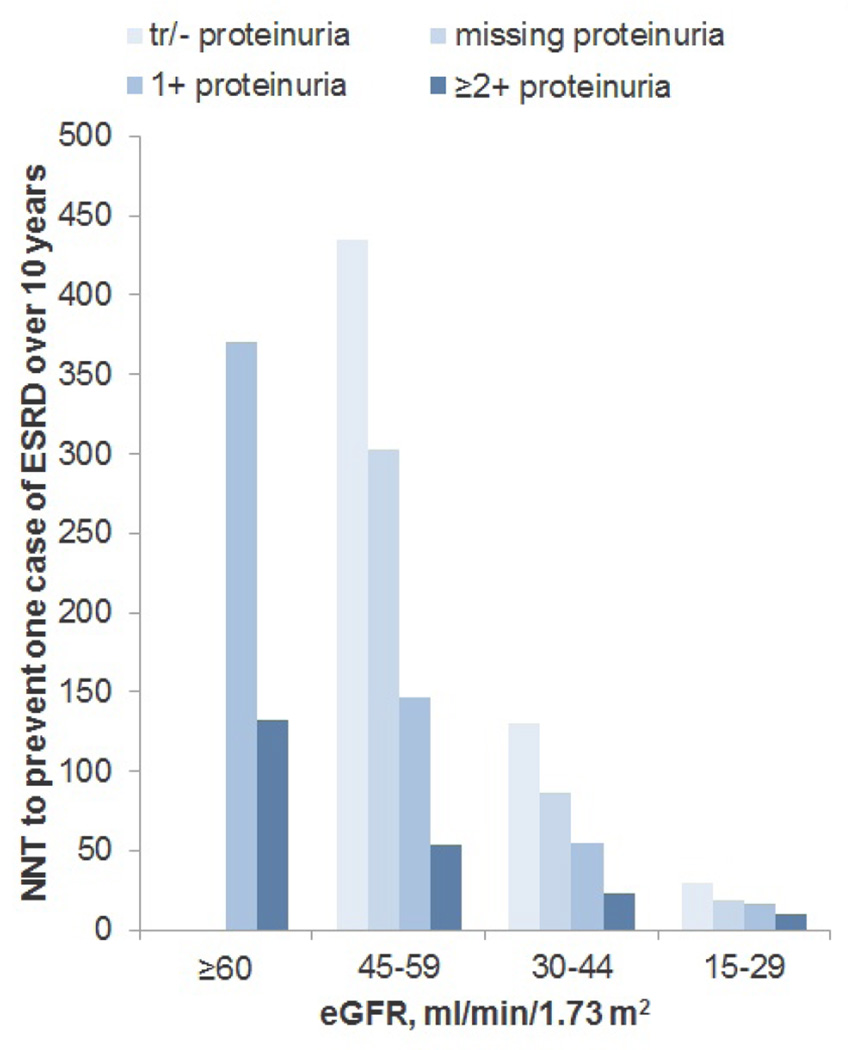

Median survival for members of the study cohort was 6.7 years (25th to 75th percentiles, 3.2 to 11.4 years), ranging from 8.1 years for patients with an eGFR 45–59 ml/min/1.73 m2 negative/trace proteinuria to 3.1 years for patients with an eGFR 15–29 ml/min/1.73 m2 and ≥ 2+ proteinuria (Table 3). Overall, 23.3% died within three years and 68.6% died within 10 years of cohort entry. Ten year mortality rates ranged from 60.6% of those with an eGFR 45–59 ml/min/1.73 m2 and negative/trace proteinuria to 95% of those with an eGFR 15–29 ml/min/1.73 m2 and ≥ 2+ proteinuria. Overall, 3.3% of patients reached ESRD within ten years of cohort entry, ranging from 0.78% of those with an eGFR 45–59 ml/min/1.73 m2 and negative/trace proteinuria to 35.05% of those with an eGFR 15–29 ml/min/1.73 m2 and ≥ 2+ proteinuria (Figure 1; eTable 1). Corresponding NNTs ranged from 10 to 435 and 73% of cohort members belonged to a group for whom the NNT exceeded 100 over the ten year follow-up period.

Table 3.

Median survival and three year and ten year mortality rates by eGFR and level of proteinuria

| Leve l of eGFR (ml/min/1.732) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of proteinuria |

≥ 60 (n=17,089) | 45–59 (n=223,119) | 30–44 (n=103,671) | 15–29 (n=27,591) | ||||||||

| Median survival (25th,75th percentiles), y |

% mortality | Median survival (25th,75th percentiles), y |

% mortality | Median survival (25th,75th percentiles), y |

% mortality | Median survival (25th,75th percentiles), y |

% mortality | |||||

| 3y | 10y | 3y | 10y | 3y | 10y | 3y | 10y | |||||

| Negative/trace (n=137,175) |

NA | NA | NA | 8.1 (4.2, −) | 17.4 | 60.6 | 6.1 (2.9, 10.2) | 25.8 | 74.0 | 3.9 (1.7, 7.2) | 40.5 | 87.3 |

| 1+ protein (n=26,655) |

6.1 (2.8, 10.8) | 26.6 | 71.4 | 5.8 (2.8, 9.8) | 26.6 | 75.8 | 4.7 (2.2, 8.3) | 33.8 | 83.5 | 3.5 (1.6, 6.1) | 43.6 | 92.4 |

| ≥ 2+ protein (n=22,536) |

5.2 (2.3, 9.5) | 31.1 | 77.0 | 5.0 (2.4, 8.7) | 31.7 | 81.6 | 4.1 (1.9, 7.2) | 38.4 | 87.9 | 3.1 (1.5, 5.5) | 48.6 | 95.0 |

| Unmeasured (n=185,104) |

NA | NA | NA | 8.0 (4.0, −) | 18.2 | 61.5 | 5.8 (2.8, 10.0) | 26.9 | 75.1 | 3.7 (1.7, 6.7) | 42.5 | 89.4 |

The median 25th and 75th percentiles of survival time represent the time point at which 50%, 25%, and 75% of group members had died, respectively. For some groups fewer than 75% of cohort members had died at the time of most recent mortality follow-up in July, 2013. For these groups the 75th percentile of survival is represented by a dash. Abbreviations: eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate; y years since cohort entry

Figure 1.

Number needed to treat to prevent one case of ESRD over ten years of follow-up assuming a 30% reduction in relative risk

Sensitivity analyses: Among those with diabetes, the three year NNT ranged from 14 to 2500 and 89% of patients belonged to a group with an NNT greater than 100 (eTable 2). Among patients not receiving an ACE inhibitor or ARB at cohort entry (n=230,823), the three year NNT ranged from 16 to 3333 and 93% belonged to a group with an NNT greater than 100 (eTable 3). When the definition of ESRD was expanded to include death with an eGFR<15 ml/min/1.73 m2, the three year NNT ranged from 12 to 588 and 91% of cohort members belonged to a group with an NNT greater than 100 (eTable 4). When we applied a 23% instead of a 30% relative risk reduction for ESRD to the overall cohort, the three year NNT ranged from 21 to 3333 and 93% of patients belonged to a group with an NNT greater than 100. A 56% relative risk reduction conferred thee year NNTs ranging from 8 to 1667 and 91% of patients belonged to a group with an NNT greater than 100.

Discussion

Major ESRD prevention trials have achieved NNTs of between 9 and 25 over trial durations of 2.6 to 3.4 years, with relative risk reductions of between 23% and 56% in populations with a baseline risk of ESRD between 14.8% and 25.5% during follow-up (18–21). When extrapolated to this real-world cohort of adults aged 70 years and older with CKD, a treatment effect within this range would be expected to yield NNTs ranging from 16 for those at highest risk for ESRD to 2,500 for those at lowest risk, with the vast majority of patients belonging to groups with an NNT greater than 100.

Older adults with limited life expectancy and complex comorbidity must often choose between a large number of recommended interventions intended to restore or maintain health (6, 13). End-stage renal disease is but one example of the many disease outcomes for which preventive interventions are available and may be recommended in an older adult. Information on the NNT to achieve a given clinical outcome can be useful in this context because it conveys information on the effort needed to achieve a treatment effect in a way that can be readily understood by patients and providers (23–25). The most effective treatments have NNTs close to 1, indicating that very few patients must be treated in order to achieve the desired outcome in a single patient. As the NNT increases, the marginal benefit to the individual patient decreases. While fixed NNT thresholds are often used to define effectiveness (26), the NNT and its counterpart—the number needed to harm—are appealing precisely because they allow for flexibility in how individual patients weigh the benefits and burdens of different treatments.

Inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system is the ESRD preventive strategy that is most strongly supported by the results of randomized controlled clinical trials (16). Trials supporting the effectiveness of these agents for prevention of ESRD enrolled mainly younger participants who were at relatively high risk for this outcome, especially those with proteinuria (15–17). In a real-world cohort of older adults with CKD, we observed much greater heterogeneity in baseline risk of ESRD compared with trial populations, leading to much larger variation in the NNT for an equivalent degree of relative risk reduction. In general, only among the small subset of patients with the lowest levels of eGFR and highest levels of proteinuria did a 30% reduction in relative risk yield NNTs comparable to those reported in the aforementioned trials. NNTs were far higher than this for the large majority of patients with earlier stages of CKD, particularly those with lower levels of proteinuria. If anything, these results probably overestimate the expected benefit of currently available interventions to prevent ESRD among members of this cohort given the paucity of evidence to support the efficacy of ACE inhibitors and ARBs for ESRD prevention in older adults with CKD and those without proteinuria (15, 27).

Clinical trials of interventions targeted at outcomes such as ESRD that may take many years to develop must often balance the need to optimize power with pragmatic constraints on trial recruitment and duration. Selection of participants at high risk for the outcome of interest can help to support these opposing goals. However, extrapolation of treatment effects in high risk trial populations to real-world populations at lower risk rests on the assumption that similar benefits will accrue over longer periods of time. This assumption may not be justified in patients at much lower risk for the outcome and/or with more limited life expectancy. To evaluate the potential impact of longer term exposure to the treatment effect, we applied the same 30% relative risk reduction over a ten year time frame. Ten year NNTs represent an optimistic estimate of the NNT had the exposure been extended over the remaining lifetime of the 68.6% of cohort members who died during this time frame. Even over this longer follow-up period, most cohort members belonged to groups for which the NNT far exceeded those achieved in trial populations over much shorter periods of time.

The simulation described here is intended to illustrate the potential importance of interpreting treatment effects from clinical trials in the context of risk information from real-world clinical settings. Our study is not intended to provide all of the information that would be needed to support treatment decisions about ESRD prevention among older adults in the clinical setting. First, interventions to prevent ESRD may also favorably impact a range of other desired treatment targets (e.g., doubling of serum creatinine, movement to a more advanced stage of kidney disease, reduction in cardiovascular risk and mortality). NNTs for interventions targeted at outcomes that are more common than ESRD (e.g., loss of eGFR) or that simultaneously reduce the risk of both ESRD and death would be expected to be lower than those reported here for ESRD. Second, we assumed equal efficacy in all patients (i.e., the same reduction in relative risk for all groups). In reality, the efficacy of interventions to prevent ESRD may also vary depending on patient characteristics such as level of renal function and proteinuria (16, 17, 28). Because older adults and those without proteinuria have generally been excluded from major randomized trials of interventions targeted at ESRD, the efficacy of these interventions at older ages and in patients without proteinuria is uncertain (15, 28). Third, we assumed that patients with similar levels of eGFR and proteinuria had a similar baseline risk of ESRD. However, as for survival time, the risk of ESRD probably varies even within these strata (29). Finally, the overall benefit of an intervention depends on the relationship between effectiveness and harm (12, 30), and the harms of interventions to prevent ESRD probably differ between real-world populations of older adults with CKD and trial populations.

Study limitations include first that our results for this predominantly male cohort may not be generalizable to older women with CKD. Because rates of ESRD are higher in men than in women (31), the results presented here probably overestimate the benefit of an equivalent reduction in relative risk among populations with a more balanced gender distribution. Second, information on level of proteinuria was missing for a substantial number of cohort patients. Nevertheless, the percentage of cohort members missing information on proteinuria is similar to that reported for other real-world cohorts defined by the presence of serum creatinine measures (32–34). We chose to retain these patients in the cohort in order to be able to assess the NNT for all groups within the population with an eGFR<60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Finally, ten year NNTs may be overly optimistic given that percent relative risk reduction for any intervention is likely to diminish as the size of the unaffected population decreases.

Differences in baseline risk and life expectancy may substantially modify the benefit of ESRD preventive interventions when applied to real-world populations of older adults compared with trial populations. This study highlights the importance of interpreting treatment effects from randomized controlled trials in the context of risk information from real-world clinical settings. This may be a particularly relevant consideration in older adults because they are often underrepresented in clinical trials and their risk for experiencing the outcome of interest during their remaining lifetime may be very different than for younger trial populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms. Whitney Showalter, Mr. Jeff Todd-Stenberg, and Dr. Charles Maynard for providing administrative and material support for this project. Dr. O’Hare receives research funding from CDC, NIA and VA Health Services Research and Development and Royalties from UpToDate. Dr. Hotchkiss receives funding from the Chief Business Office, Veteran’s Healthcare Administration. Dr. Kurella Tamura served on a scientific advisory board for Amgen. Dr Hemmelgarn is supported by the Roy and Vi Baay Chair in Kidney Research. Dr. Do is employed by Amgen but his work for this project was completed in his role as an employee of the University of Washington and the VA Puget Sound Healthcare System and was unrelated to his employment at Amgen. Dr. Larson receives funding from NIH. Dr. Covinsky is supported by K24AG029812 from the NIA. These funding sources had no role in the design or interpretation of the study.

References

- 1.Van Spall HG, Toren A, Kiss A, Fowler RA. Eligibility criteria of randomized controlled trials published in high-impact general medical journals: a systematic sampling review. JAMA. 2007;297(11):1233–1240. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.11.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee PY, Alexander KP, Hammill BG, Pasquali SK, Peterson ED. Representation of elderly persons and women in published randomized trials of acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2001;286(6):708–713. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.6.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gurwitz JH, Col NF, Avorn J. The exclusion of the elderly and women from clinical trials in acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1992;268(11):1417–1422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heiat A, Gross CP, Krumholz HM. Representation of the elderly, women, and minorities in heart failure clinical trials. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(15):1682–1688. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.15.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tinetti ME, Fried TR, Boyd CM. Designing health care for the most common chronic condition--multimorbidity. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2493–2494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294(6):716–724. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fried TR, Tinetti ME, Iannone L. Primary care clinicians’ experiences with treatment decision making for older persons with multiple conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(1):75–80. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried TR, McGraw S, Agostini JV, Tinetti ME. Views of older persons with multiple morbidities on competing outcomes and clinical decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1839–1844. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tinetti ME, McAvay GJ, Fried TR, Allore HG, Salmon JC, Foody JM, et al. Health outcome priorities among competing cardiovascular, fall injury, and medication-related symptom outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(8):1409–1416. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01815.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tinetti ME, Fried T. The end of the disease era. Am J Med. 2004;116(3):179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gill TM. The central role of prognosis in clinical decision making. JAMA. 2012;307(2):199–200. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: a framework for individualized decision making. JAMA. 2001;285(21):2750–2756. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.21.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reuben DB. Medical care for the final years of life: “When you’re 83, it’s not going to be 20 years”. JAMA. 2009;302(24):2686–2694. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fried TR, Tinetti ME, Iannone L, O’Leary JR, Towle V, Van Ness PH. Health outcome prioritization as a tool for decision making among older persons with multiple chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(20):1854–1856. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Hare AM, Kaufman JS, Covinsky KE, Landefeld CS, McFarland LV, Larson EB. Current guidelines for using angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II-receptor antagonists in chronic kidney disease: is the evidence base relevant to older adults? Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(10):717–724. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-10-200905190-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fink HA, Ishani A, Taylor BC, Greer NL, MacDonald R, Rossini D, et al. Screening for, monitoring, and treatment of chronic kidney disease stages 1 to 3: a systematic review for the U.S; Preventive Services Task Force and for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(8):570–581. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-8-201204170-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Uhlig K. Which antihypertensive agents in chronic kidney disease? Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(3):213–215. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-3-200602070-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(12):861–869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Bain RP, Rohde RD. The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. The Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(20):1456–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311113292004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Gherardi G, Garini G, Zoccali C, Salvadori M, et al. Renoprotective properties of ACE-inhibition in non-diabetic nephropathies with non-nephrotic proteinuria. Lancet. 1999;354(9176):359–364. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10363-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agodoa LY, Appel L, Bakris GL, Beck G, Bourgoignie J, Briggs JP, et al. Effect of ramipril vs amlodipine on renal outcomes in hypertensive nephrosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285(21):2719–2728. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.21.2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sohn MW, Arnold N, Maynard C, Hynes DM. Accuracy and completeness of mortality data in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Popul Health Metr. 2006;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laupacis A, Sackett DL, Roberts RS. An assessment of clinically useful measures of the consequences of treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(26):1728–1733. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198806303182605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nuovo J, Melnikow J, Chang D. Reporting number needed to treat and absolute risk reduction in randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2002;287(21):2813–2814. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.21.2813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cook RJ, Sackett DL. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. BMJ. 1995;310(6977):452–454. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6977.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ridker PM, MacFadyen JG, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Kastelein JJ, et al. Number needed to treat with rosuvastatin to prevent first cardiovascular events and death among men and women with low low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein: justification for the use of statins in prevention: an intervention trial evaluating rosuvastatin (JUPITER) Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2(6):616–623. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.848473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rahman M, Pressel S, Davis BR, Nwachuku C, Wright JT, Jr, Whelton PK, et al. Renal outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients treated with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or a calcium channel blocker vs a diuretic: a report from the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(8):936–946. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.8.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Upadhyay A, Earley A, Haynes SM, Uhlig K. Systematic review: blood pressure target in chronic kidney disease and proteinuria as an effect modifier. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(8):541–548. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-8-201104190-00335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tangri N, Stevens LA, Griffith J, Tighiouart H, Djurdjev O, Naimark D, et al. A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA. 2011;305(15):1553–1559. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zermansky A. Number needed to harm should be measured for treatments. BMJ. 1998;317(7164):1014. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7164.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eriksen BO, Ingebretsen OC. The progression of chronic kidney disease: a 10-year population-based study of the effects of gender and age. Kidney Int. 2006;69(2):375–382. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiss JW, Johnson ES, Petrik A, Smith DH, Yang X, Thorp ML. Systolic blood pressure and mortality among older community-dwelling adults with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56(6):1062–1071. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall YN, Choi AI, Chertow GM, Bindman AB. Chronic kidney disease in the urban poor. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(5):828–835. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09011209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Lloyd A, James MT, Klarenbach S, Quinn RR, et al. Relation between kidney function, proteinuria, and adverse outcomes. JAMA. 2010;303(5):423–429. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.