Abstract

Rumination has been shown to be important in both the maintenance and severity of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder (MDD). Increased rumination has also been linked to perceptions of increased stress, which in turn are significantly associated with increased PTSD severity. The present study sought to examine this relationship in more detail by means of a mediation analysis. Forty-nine female survivors of interpersonal violence who met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text rev.; DSM-IV-TR) criteria for PTSD were administered the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS), the Ruminative Thought Style Questionnaire (RTS), the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), and the Beck Depression Inventory–II (BDI-II). Results indicated that perceived stress mediates the relationship between rumination and PTSD, but did not do so after controlling for depression. Such results provide further evidence for the overlap between PTSD and MDD, and, in broader clinical practice, translate to a sharper focus on rumination and perceived stress as maintenance factors in both disorders.

Keywords: PTSD, domestic violence, child abuse, sexual assault

Perceived stress is defined as “the degree to which situations in one’s life are appraised as stressful” (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983, p. 387). Perceived stress provides useful information beyond more objective measures of exposure to stressful events because it describes the individual’s interpretation of these stressors and his or her anticipated ability to negotiate such challenges. As such, research investigating the relationship between posttraumatic stress and more global perceived stress has found that increased posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom severity and higher levels of perceived stress frequently co-occur in a variety of populations (e.g., Besser, Neria, & Haynes, 2009; Frasier et al., 2004; Laganá & Schuitevoerder, 2009; Qu et al., 2012). Perceived stress has also been identified as a specific risk factor in the development (Fincham, Altes, Stein, & Seedat, 2009; Haisch & Meyers, 2004) and experience (Besser et al., 2009) of PTSD. Therefore, perceived stress may play a role in potentiating the severity of PTSD symptoms.

Rumination has also been shown to be an important maintenance factor in the manifestation and maintenance of PTSD (see Elwood, Hahn, Olatunji, & Williams, 2009, for a comprehensive review). Considered the core cognitive feature of major depressive disorder (MDD), rumination is described as the tendency to think continuously and passively about negative events and individual distress (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). When one considers how comorbidity rates of MDD and PTSD run as high as 48% (e.g., Kaufman & Charney, 2000; Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995; King-Kallimanis, Gum, & Kohn, 2009; Nixon, Resick, & Nishith, 2004), this concurrence is suggestive of shared features, which may include the tendency to ruminate upon negative experiences. Indeed, Ehlers and Clark (2000) proposed a cognitive model of PTSD in which a continuous negative evaluation of the trauma via constant rumination and memory disruption maintains symptomatology. The same authors (Ehlers & Clark, 2008) later suggest that rumination is intended to reduce the current sense of threat and regain cognitive control. Rumination may thus serve as an avoidant strategy that ultimately maintains PTSD by allowing individuals to focus on the highly verbal yet superficial aspect of how and why the trauma happened, rather than processing the underlying emotional content (Michael, Halligan, Clark, & Ehlers, 2007).

Finally, rumination and perceived stress themselves may be interrelated constructs. Research on college undergraduates found two well-validated measures of rumination and perceived stress to be correlated at .44 (Morrison & O’Connor, 2005). This association may be best explained by a diathesis-stress model wherein increased rumination following a stressful negative life event may serve to increase subsequent experiences of psychopathology, particularly symptoms of depression (Morrison & O’Connor, 2005; Robinson & Alloy, 2003). As rumination and perceived stress appear to be important factors in the maintenance of PTSD, examining a model that addresses the relationship between these constructs within the framework of PTSD may help inform subsequent treatment of this disorder. Therefore, the present study sought to examine the relationship between rumination, perceived stress, and PTSD symptomatology within a population of female interpersonal violence survivors. Specifically, the study hypothesized that perceived stress mediates the relationship between rumination and PTSD in this particular sample, such that rumination acts to increase PTSD severity by in turn increasing the level of perceived stress.

Method

Participants and Procedure

As part of a larger neuroimaging and PTSD treatment trial, 49 women who completed measures assessing PTSD severity, level of perceived stress, and frequency of ruminative thoughts were included in the current sample. Participants were recruited via advertisements in the community and through the student subject pool of a large, Midwestern university. All participants were between the ages of 18 and 55, had experienced interpersonal violence—defined as some form of physical and/or sexual assault—as children or adults, and met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text rev.; DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000) diagnostic criteria for PTSD according to scores on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; described below). Participants were excluded from the study along several criteria, including but not limited to prescription psychotropic medications; current comorbid disorders such as bipolar disorder, psychosis, or personality disorders; and traumatic brain injury.

Measures

The CAPS

PTSD severity was assessed by the CAPS, a semi-structured diagnostic interview that queries all 17 symptoms of PTSD for frequency of occurrence and severity of impairment in the past month (see Blake et al., 1990). A variety of psychometric studies conducted over the years have shown the CAPS to be internally and externally consistent (e.g., Blake et al., 1990; Hovens et al., 1994; Hyer, Summers, Boyd, Litaker, & Boudewyns, 1996). Blake and colleagues’ (1990) original scoring rules were implemented, such that each individual symptom was considered to be “present” with a frequency score of at least 1 and a severity score of at least 2. Participants were considered PTSD positive if symptom guidelines according to the DSM-IV-TR were met—that is, participants endorsed at least one reexperiencing symptom, at least three avoidance/numbing symptoms, and at least two hypervigilance symptoms.

Beck Depression Inventory–II (BDI-II)

The BDI-II is a 21-item self-report measure of a respondent’s experience of depressive symptomatology (see Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). Item responses fall on a Likert-type scale with ranges of 0–3, each item assessing a separate symptom of depression in accordance with diagnostic criteria in the DSM (4th ed.; DSM-IV; APA, 1994). Coefficient alpha for the BDI-II was found to be .91 in a sample of college students, with a sensitivity rate of 71% (Dozois, Dobson, & Ahnberg, 1998).

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

The PSS is a 14-item self-report measure of a respondent’s overall stress as experienced in the past month (see Cohen et al., 1983). In addition to items querying general levels of stress and nervousness, the PSS also examines the respondent’s sense of control and efficacy in his or her recent life. Item responses range from 0 = never to 4 = very often, and seven items are reverse-scored to produce a total score as a measure of overall subjective stress. Coefficient alpha for the PSS has been found to be .84 or higher, and the measure also demonstrated good test–retest reliability in two college student samples (Cohen et al., 1983).

Ruminative Thought Style Questionnaire (RTS)

The RTS is a 20-item self-report measure of a respondent’s overall tendency toward ruminative thinking (Brinker & Dozois, 2009). Participants rate items according to how well each item describes his or her pattern of thinking, where 1 = not at all and 7 = very well. Total scores range from 20 to 140, with higher scores indicating a greater tendency toward rumination. Furthermore, psychometric analyses of the RTS have concluded that the measure demonstrates good internal (coefficient α = .87) and test–retest reliability (r = .80, p < .01); the RTS is also well correlated with other measures of repetitive thought, as well as measures of psychopathology associated with rumination, such as depression (Brinker & Dozois, 2009).

Results

Participants averaged 31.4 years of age, and most identified as either Caucasian (n = 27) or African American (n = 22). Average education was 14.68 years (SD = 3.21). Participants reported an average CAPS total score of 65.02 (SD = 17.6), PSS score of 34.23 (SD = 7.82), BDI score of 25.72 (SD = 9.83), and RTS score of 97.73 (SD = 22.9). The PSS and RTS were found to be elevated when compared with the normative scores upon which the measures were standardized—23.18 and 88.00, respectively (Brinker & Dozois, 2009; Cohen et al., 1983). Internal consistency values for the CAPS (Cronbach’s α =.86), PSS (Cronbach’s α =.86), the BDI (Cronbach’s α =.88), and the RTS (Cronbach’s α =.93) in the current study all demonstrated excellent reliability.

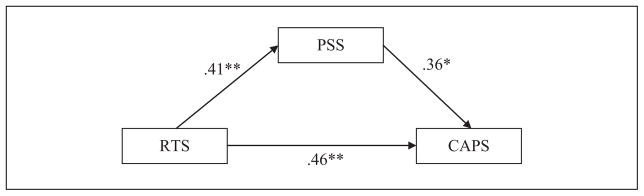

To establish the prerequisites for mediation analysis, linear regressions were conducted among all variables to determine the significance of individual paths. Analyses indicated that the RTS significantly predicted the CAPS, β = .46, t(43) = 3.339, p = .002, and the RTS significantly predicted the PSS, β = .41, t(49) = 3.09, p = .003. Subsequent multiple regression using the RTS and PSS as predictors of CAPS scores was also significant, β = .359, t(43) = 2.563, p = .014. Thus, prerequisites for subsequent mediation analysis were met.

Sobel’s path analysis was then subsequently used to determine whether mediation was present. Analyses indicated partial mediation (t = 2.035, df = 41, p < .05), such that PSS scores appear to significantly mediate the relationship between RTS and CAPS scores in this sample. Figure 1 depicts a path diagram of the mediation analysis. The analyses were then repeated to determine whether such findings still held after controlling for depression. BDI scores were thus entered as a covariate, and the model was rerun. Results indicated that the paths between RTS and PSS scores (p = .21) and between PSS and CAPS scores (p = .47) became nonsignificant after depression was controlled. Therefore, PSS scores no longer functioned as a significant mediator between RTS and CAPS scores after controlling for depression.

Figure 1.

Standardized regression coefficients (β) for the relationship between frequency of rumination and PTSD severity, as mediated by levels of perceived stress.

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; PSS = Perceived Stress Scale; RTS = Ruminative Thought Style Questionnaire; CAPS = Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyze the relationship among rumination, perceived stress, and PTSD. Individual regression analyses indicated that these constructs are all closely related, confirming findings from previous research (e.g., Frasier et al., 2004; Michael et al., 2007; Morrison & O’Connor, 2005). Results of a mediational analysis initially indicated that perceived stress partially mediates the relationship between rumination and PTSD. However, these results did not hold after controlling for depression. Such results are unsurprising given the high degree of overlap between depression and PTSD, and indeed, one may extrapolate from the findings of this study that the cognitive patterns that characterize PTSD and depression may be more similar than previously assumed. Such similarities suggest treatment for PTSD may benefit from incorporating elements of depression treatment used to address rumination, especially because of the impact of rumination on perceived stress. The cognitive model for PTSD proposed by Ehlers and Clark (2000) highlights the extent to which negative trauma-related appraisal processes can negatively impact posttraumatic adaptation. This model may be applied to the findings of the current study by considering how metacognition may lead an individual to appraise increased trauma-related rumination as indicative of enduring posttraumatic dysfunction. Such an appraisal may decrease the individual’s sense of self-efficacy and control, thereby increasing levels of perceived stress. In accordance with such theory, clinicians may wish to address rumination at the outset of PTSD treatment through psychoeducation and direct intervention, such that patients may be less likely to consider themselves more stressed and less efficacious due to continuous revisiting of the traumatic memory. Mindfulness-based techniques, which encourage acceptance of current thoughts without becoming attached to their meaning, may also be especially useful for addressing rumination in this way.

Limitations of the current study include the sole use of a female sample, which may not generalize to men. Furthermore, all participants reported an interpersonal assault history. Examination of the relationship of rumination and PTSD based on other traumatic events may be warranted. In addition, participants were part of a broader PTSD treatment study, meaning they were seeking treatment at the time of participation. Therefore, the current sample may be composed of individuals who perhaps were experiencing more perceived stress due to trauma-related ruminative thoughts, and thus were motivated to seek treatment for these difficulties. This study was also underpowered (statistical power = 0.45 for a small to medium effect size; see Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007), so future research may wish to utilize larger samples to better inform the results. Finally, the data utilized in the analysis were cross-sectional. According to Maxwell and Cole (2007), mediational analyses are designed to examine longitudinal changes over time. Therefore, results from this study may only be considered preliminary. Despite these limitations, the results suggest that ruminative tendencies and level of perceived stress are important factors to consider with regard to the maintenance and treatment of PTSD symptoms. Future research may encompass an exploration of how age at trauma onset (e.g., child vs. adult) factors into such a model, especially given how the severity and consequences of rumination may increase as a function of length of time since the trauma. Future research may also wish to examine rumination and perceived stress as dimensional constructs within related forms of psychopathology, particularly MDD. Greater emphasis is being placed on the dimensional classification of disorders in the DSM (5th ed.; DSM-5; APA, 2013), and understanding interrelated aspects of psychological disorders is central to this effort. Rumination and perceived stress warrant consideration as cognitive dimensions, given their salience in MDD and PTSD. Continuous assessment of these two constructs throughout the course of PTSD treatment may thus better inform treatment approach and prognosis by providing clinicians with another index of PTSD symptom severity.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported in part by National Institute of Mental Health Grants K23 MH090366-01 and 1RC1 MH089704-01.

Biographies

Emily Hu, MA, is a doctoral student in clinical psychology at the University of Missouri–St. Louis. Her research interests include etiology and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder, as well as the intersection of trauma and multicultural psychology.

Ellen M. Koucky, MA, is a PhD candidate in clinical psychology at the University of Missouri–St. Louis. She is currently a predoctoral intern at the Cincinnati VA Medical Center. Her research focuses on the etiology and treatment of trauma-related symptoms, posttraumatic cognitions, and social support.

Wilson J. Brown, MA, is a doctoral student at the University of Missouri–St. Louis where he studies clinical psychology. His research focuses on the role of emotion regulation within comorbid anxiety and mood disorders. He completed his undergraduate studies at Pennsylvania State University.

Steven E. Bruce, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Missouri–St. Louis. His research interests and clinical specializations include the treatment of anxiety and affective disorders, particularly posttraumatic stress disorder. Specifically, he is interested in conducting translational research incorporating neuroimaging and psychophysiological assessment as predictors and outcomes of treatment response.

Yvette I. Sheline, MD, is a professor of psychiatry, radiology, and neurology at Washington University School of Medicine and director of the Center for Depression, Stress, and Neuroimaging. Her extensive research experience has focused on neuroimaging in the diagnosis and treatment of major depression and posttraumatic stress disorders, and has conducted studies of emotional regulation in mood disorders using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) for the past decade. She maintains a productive collaboration with Dr. Steve Bruce, director of the Center for Trauma Recovery at the University of Missouri–St. Louis. Future goals are to examine populations suffering from interpersonal trauma using her expertise in resting state functional connectivity.

Footnotes

Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Besser A, Neria Y, Haynes M. Adult attachment, perceived stress, and PTSD among civilians exposed to ongoing terrorist attacks in Southern Israel. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;47:851–857. [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Klauminzer G, Charney DS, Keane TM. A clinician rating scale for assessing current and lifetime PTSD: The CAPS-I. Behavior Therapist. 1990;13:187–188. [Google Scholar]

- Brinker JK, Dozois DJ. Ruminative thought style and depressed mood. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65:1–19. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozois DJA, Dobson KS, Ahnberg JL. A psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10(2):83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Clark DM. A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2000;38:319–345. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Clark DM. Post-traumatic stress disorder: The development of effective psychological treatments. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;62:11–18. doi: 10.1080/08039480802315608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwood LS, Hahn KS, Olatunji BO, Williams NL. Cognitive vulnerabilities to the development of PTSD: A review of four vulnerabilities and the proposal of an integrative vulnerability model. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:87–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham DS, Altes LK, Stein DJ, Seedat S. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in adolescents: Risk factors versus resilience moderation. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2009;50:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasier PY, Belton L, Hooton E, Campbell MK, DeVellis B, Benedict S, Meier A. Disaster down East: Using participatory action research to explore intimate partner violence in eastern North Carolina. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31(4):69S–84S. doi: 10.1177/1090198104266035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, MacKinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science. 2007;18:233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haisch DC, Meyers LS. MMPI-2 assessed post-traumatic stress disorder related to job stress, coping, and personality in police agencies. Stress & Health. 2004;20:223–229. doi: 10.1002/smi.1020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hovens J, Van der Ploeg HM, Bramsen I, Klaarenbeek MTA, Schreuder BJN, Rivero VV. The development of the Self-Rating Inventory for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1994;90:172–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyer LA, Summers MN, Boyd S, Litaker M, Boudewyns PA. Assessment of older combat veterans with the clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1996;9:587–593. doi: 10.1007/BF02103667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Charney D. Comorbidity of mood and anxiety disorders. Depression and Anxiety. 2000;12(Suppl 1):69–76. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)12:1+<69::AID-DA9>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King-Kallimanis B, Gum AM, Kohn R. Comorbidity of depressive and anxiety disorders for older Americans in the national comorbidity survey-replication. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009;17:782–792. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ad4d17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laganá L, Schuitevoerder S. Pilot testing a new short form screen for older women’s PTSD symptomatology. Educational Gerontology. 2009;35:732–751. doi: 10.1080/03601270802708442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE, Cole DA. Bias in cross-sectional analysis of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:23–44. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael T, Halligan SL, Clark DM, Ehlers A. Rumination in post-traumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2007;24:307–317. doi: 10.1002/da.20228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison R, O’Connor RC. Predicting psychological distress in college students: The role of rumination and stress. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;61:447–460. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon RD, Resick PA, Nishith P. An exploration of comorbid depression among female victims of intimate partner violence with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;82:315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:569–582. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Z, Tian D, Zhang Q, Wang X, He H, Zhang X, Xu F. The impact of the catastrophic earthquake in China’s Sichuan province on the mental health of pregnant women. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;136:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MS, Alloy LB. Negative cognitive styles and stress-reactive rumination interact to predict depression: A prospective study. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:275–292. [Google Scholar]