Abstract

The first home pregnancy test was introduced in 1976. Since then, pregnancy tests have become the most common diagnostic assay used at home. Pregnancy tests use antibodies to detect human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). It is an ideal marker of pregnancy since it rises rapidly and consistently in early pregnancy and can be detected in urine. The most advanced home pregnancy test currently available assesses the level of hCG found in urine and claims to provide women with reliable results within just a few weeks of pregnancy. Today, over 15 different types of home pregnancy test are available to buy over the counter in Germany. Many tests claim to be highly accurate and capable of detecting pregnancy before the next monthly period is due, although claims such as 8 days prior to menstruation are unrealistic. However, users and healthcare professionals should be aware that, although all are labelled as CE, there are currently no standard criteria for testing performance and claims. This review provides an overview of the development of home pregnancy tests and the data on their efficacy together with an analysis of published data on the accuracy of hCG for the detection of early pregnancy and studies on the use of home-based pregnancy tests. Preliminary data on some home pregnancy tests available in Germany are presented which indicate that many results do not match the claims made in the package insert. Healthcare professionals and women should be aware that some of the claims made for home pregnancy tests are inconsistent and that common definitions and testing criteria are urgently needed.

Key words: pregnancy, pregnancy test, hCG

Abstract

Zusammenfassung

Der erste Urinschwangerschaftstest wurde 1976 vorgestellt und seitdem gehören diese Tests zu den am häufigsten durchgeführten Laboruntersuchungen in der Eigenanwendung. Schwangerschaftstests gehören nach der europäischen Richtlinie 98/79/EG zu den In-vitro-Diagnostika der Medizinprodukte. Sie sind keiner Risikoliste zugeordnet. Anders als in den USA führt weder das Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte (BMfArM) noch die Zentralstelle der Länder für Gesundheitsschutz bei Arzneimitteln und Medizinprodukten (ZLG) eine Liste geprüfter und zugelassener Schwangerschaftstests. Im vergangenen Jahr war zwischenzeitlich geplant, die hCG-Bestimmung aus dem Urin in der frauenärztlichen Praxis einer externen Qualitätskontrolle zu unterziehen, ohne dass kommerzielle Schwangerschaftstests ihre Genauigkeit und Sensitivität unter Beweis stellen mussten und es bis heute auch keine Standards für eine solche Überprüfung gibt. In Apotheken und Drogeriemärkten in Deutschland sind derzeit über 15 verschiedene Heim-Schwangerschaftstests erhältlich. Viele dieser Schwangerschaftstests behaupten, mit einer hohen Genauigkeit und Empfindlichkeit hCG im Urin festzustellen, oft angeblich bereits einige Tage vor der erwarteten Periodenblutung. Diese Arbeit gibt einen Überblick über die Entwicklung von Urin-Schwangerschaftstests sowie die vorhandenen Daten zur Genauigkeit und Sensitivität der hCG-Messung und informiert über neue Entwicklungen. Es werden erste Daten einer vergleichenden Überprüfung in Deutschland verkaufter Schwangerschaftstests vorgestellt, die zeigen, dass nicht viele den Versprechungen auf ihren Verpackungen genügen. Allen Benutzern von Heim-Schwangerschaftstests müssen die Grenzen dieser Methode und die Anfälligkeit einzelner Tests bekannt sein, um nicht falsche Schlussfolgerungen zu ziehen. In Anbetracht der großen Bedeutung des Ergebnisses eines Schwangerschaftstests für jede einzelne Frau ist auch in Deutschland dringend eine offizielle Prüfung und Zulassung einzelner Tests vor dem Verkauf und später eine Produktüberwachung notwendig.

Schlüsselwörter: Schwangerschaft, Hormone, hCG, Schwangerschaftstest

Introduction

Home pregnancy testing, which is done via the detection of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) in urine, has made considerable progress since its inception in 1976. Today in Germany, around 15–20 different home pregnancy tests are sold over the counter (in pharmacies and drugstores), a selection of which are described in Table 1. The package inserts of most available tests claim that the accuracy of the tests are “over 99 %” and “highly sensitive”. However, the majority of these over-the-counter pregnancy tests have not been tested in independent, prospective studies and their true accuracy has not been evaluated. None of the German supervisory authorities such as the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte or BfArM, http://www.bfarm.de) or the Central Authority of the Länder for Health Protection in Medicinal Products and Medical Devices (Zentralstelle der Länder für Gesundheitsschutz bei Arzneimitteln und Medizinprodukten or ZLG, https://www.zlg.de) do not currently test or approve tests. For self-tests, such as home pregnancy tests, a technical file or design dossier is prepared, which is then reviewed by a notified body prior to marketing; this notified body must be an organisation accredited and recognised within the European Union as capable of performing conformity assessments 1. The only information currently available on the accuracy of pregnancy tests is from non-institutional and non-scientific publications 2. This review provides an important update on current scientific knowledge and published literature on urinary home pregnancy tests. It also provides urgently needed data on the accuracy of commonly available tests and discusses new developments relating to the measurement of urinary hCG to estimate pregnancy.

Table 1 Results of a preliminary evaluation of the performance of currently marketed pregnancy tests available in Germany. To perform this analysis, hCG solutions of 0, 5, 10, 25, and 50 mIU/ml (in pooled hCG-negative urine) were prepared from an initial stock solution calibrated to the WHO (World Health Organisation) 4th International Standard. The standards were all measured by AutoDELFIA (Perkin Elmer) to ensure they were within ± 5 % of target value. Results from testing of standards are expressed as total number of positive results over the number of devices tested.

| Test | Cyclotest (Schwangerschaftstest) | MedVec International (Schwangerschaftsfrühtest) | Clearblue Digital Pregnancy Test with Conception Indicator | Testamed Diagnostics (Digitaler Schwangerschaftstest) | Cyclotest (Schwangerschaftsfrühtest) | Prima Sicher (Schwangerschaftstest) | Testamed Diagnostics (Schwangerschaftsfrühtest) | Presense (Schwangerschaftsfrühtest) | Clearblue Pregnancy Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Claimed sensitivity (mIU/ml) | 25 | 10 | 25 | not stated | 12 | 25 | 25 | 10 | 25 |

| Required dipping time (seconds) | 3 | 10 | 20 | 15 | 3 | 3 | 20 | 10 | 5 |

| Reading time (minutes) | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1–3 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| hCG solutions (mIU/ml) | |||||||||

|

0/2 (1 error) | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/1 (2 errors) | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 |

|

0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/2 (1 error) | 0/3 | 0/3 | 1/3 | 0/3 | 3/3 |

|

0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/1 (2 errors) | 0/3 | 2/3 | 3/3 | 2/3 | 3/3 |

|

0/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 2/2 (1 error) | 0/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 |

|

0/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 1/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 |

| Did test match sensitivity claim? | no | No | Yes | unknown | no | yes | yes | borderline | yes |

| Price per test (amazon.de) | 4.32 € | 9.87 € | 10.95 € | 14.57 € | 6.28 € | 4.95 € | 7.02 € | not available | 3.95–5.99 € |

Human Chorionic Gonadotropin

The hormone hCG is produced very early in pregnancy by trophoblast cells. After implantation, the placenta begins to develop and produce increasing amounts of hCG. As this makes hCG a marker for implantation, this finding has been exploited to create both laboratory and home pregnancy tests.

Human chorionic gonadotropin is a glycoprotein consisting of two non-covalently linked, dissimilar subunits, known as α (91 amino acids) and β (hormone specific subunit of 145 amino acids). Multiple forms of hCG can be detected in both serum and urine, and WHO International Standards have been created for the most important forms 3, 4, 5, which include intact hCG, nicked intact hCG (where there is a nick in the β-polypeptide chain, primarily between amino acid positions 40 and 50 from the N-terminal end of the β-subunit 6, 7), free β-subunit, and free nicked β-subunit. An additional form, free β-core, is present in urine and becomes the predominant form in later pregnancy 8.

There has been much discussion on hyperglycosylated hCG (hCG-H), which originally referred to a variant of “normal” hCG with larger complex oligosaccharide side chains seen in choriocarcinoma 9. Some researchers reported that hCG-H is the predominant form in early pregnancy 10. Unfortunately, there is no reference standard available for this form of hCG, and all studies were done using a single antibody B152, which is not commercially available, so that corroboration of these findings via independent reagents has not been possible. However, it is clear that a mixture of hCG forms is typical in early pregnancy 11. Different immunoassays vary in their ability to recognise these different forms 12, although there is no evidence of any benefit in measuring one or multiple forms with regard to accuracy in detecting pregnancy 4, 5.

Human Chorionic Gonadotropin in Early Pregnancy

Eight days after conception, hCG can be detected in the maternal circulation 13; a concentration of approximately 10 mlU/ml is observed in serum between 9 and 10 days after follicular rupture 14. As the pregnancy develops, the level of hCG increases at a rate of approximately 50 % per day, reaching a peak of around 100 000 mlU/ml by week 10, after which levels decrease and remain stable at approximately 20 000 mIU/ml for the remainder of the pregnancy 14, 15.

In addition to being present in maternal serum, hCG can be detected in the urine of pregnant women, where its appearance and rise show similar patterns to those observed in the maternal circulation 16. At 9 days after conception, the mean concentration of hCG has been observed to be 0.93 mIU/ml 17, with levels increasing daily until they reach the plateaux at approximately 45 days post conception.

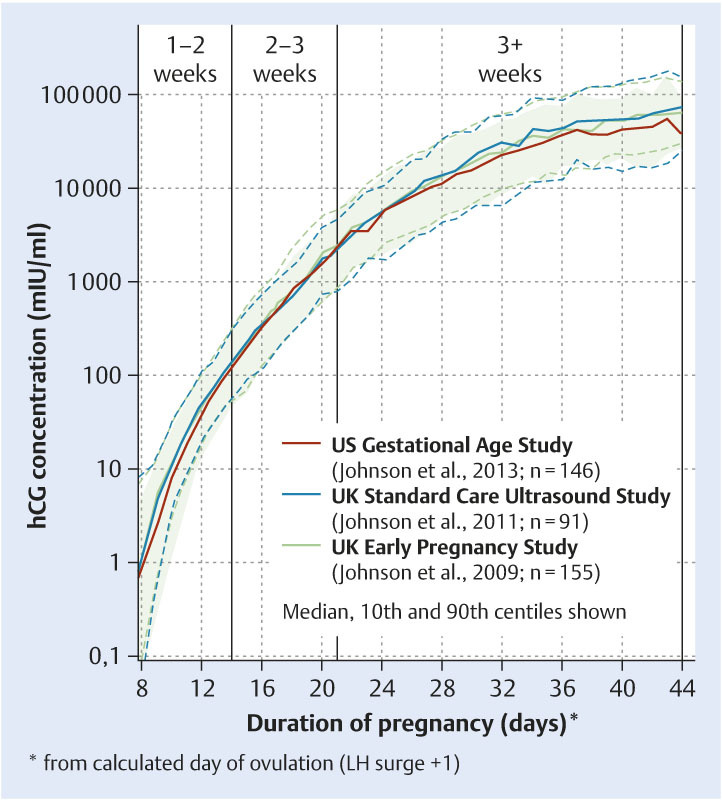

This daily increase in urinary hCG levels by approximately 50 % observed in early pregnancy was consistently noted in different studies conducted across a 5-year period, using three different cohorts of women, as shown in Fig. 1. All of the studies reported a remarkable uniformity in the rise of hCG levels in early pregnancy. This combined cohort data has been used to provide reference ranges for hCG for each day of pregnancy (Table 2). The studies reported no differences between ethnicities with regard to urinary hCG increase 18. However, levels of serum hCG in early pregnancy (day 16 following assisted reproductive technology [ART]) have been seen to be slightly lower in women with a higher pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI); this may be due to the effect of adipose tissue-derived signalling molecules on hCG secretion by the implanting embryo 19.

Fig. 1.

Daily increase in urinary hCG in early pregnancy in three different studies: The UK Early Pregnancy Study 17, the UK Standard Care Ultrasound Study 26 and the US Gestational Age Study 18. The grey area is the 10th to 90th centile band for the US Gestational Age Study 18.

Table 2 Reference ranges for urinary intact hCG for each day of pregnancy. Duration of pregnancy refers to days since ovulation (with ovulation given as LH surge + 1 day). Data was obtained from 109 UK volunteers who provided daily urine samples, starting prior to conception and continuing through early pregnancy (collection done from 23/01/12 to 12/03/13, with the approval of the local ethics committee). Mean age of the volunteers was 29.50 years (SD 4.27, median 29 years, range 21–40). hCG was measured using the AutoDELFIA immunoassay system (Perkin Elmer).

| Duration of pregnancy (days) | n | Median hCG (mIU/ml) | 10th and 90th centiles of hCG (mIU/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| hCG: human chorionic gonadotropin | |||

| 7 | 91 | 0.00 | (0.00, 0.20) |

| 8 | 102 | 0.06 | (0.00, 2.91) |

| 9 | 104 | 4.04 | (0.19, 11.32) |

| 10 | 103 | 12.23 | (3.92, 27.01) |

| 11 | 104 | 25.04 | (9.47, 57.82) |

| 12 | 98 | 48.10 | (15.72, 94.09) |

| 13 | 101 | 75.25 | (29.02, 196.95) |

| 14 | 103 | 137.19 | (45.06, 301.08) |

| 15 | 104 | 208.34 | (86.83, 464.51) |

| 16 | 107 | 333.73 | (139.19, 853.50) |

| 17 | 100 | 524.90 | (209.98, 1 313.55) |

| 18 | 105 | 813.74 | (283.89, 1 768.70) |

| 19 | 99 | 1 187.00 | (426.07, 2 976.40) |

| 20 | 104 | 1 644.70 | (662.62, 4 169.70) |

| 21 | 104 | 2 681.70 | (935.46, 6 470.40) |

| 22 | 104 | 3 066.80 | (1 071.20, 7 300.10) |

| 23 | 98 | 4 554.20 | (1 316.10, 11 043.00) |

| 24 | 99 | 5 056.80 | (1 787.40, 13 029.00) |

| 25 | 100 | 6 451.55 | (2 477.55, 15 310.00) |

| 26 | 99 | 7 692.50 | (3 157.70, 20 123.00) |

| 27 | 102 | 10 170.00 | (3 203.30, 25 863.00) |

| 28 | 103 | 11 975.00 | (4 381.60, 29 184.00) |

| 29 | 97 | 12 942.00 | (5 301.20, 33 212.00) |

| 30 | 100 | 16 109.00 | (5 793.00, 41 008.50) |

| 31 | 96 | 18 265.50 | (8 578.20, 57 419.00) |

| 32 | 101 | 26 115.00 | (9 176.30, 73 159.00) |

| 33 | 95 | 27 485.00 | (11 482.00, 70 464.00) |

| 34 | 93 | 31 189.00 | (12 852.00, 84 109.00) |

| 35 | 91 | 35 243.00 | (15 541.00, 81 680.00) |

| 36 | 92 | 35 177.50 | (12 809.00, 87 293.00) |

| 37 | 93 | 38 955.00 | (17 155.00, 101 990.00) |

| 38 | 86 | 40 431.50 | (19 484.00, 108 660.00) |

| 39 | 85 | 52 411.00 | (16 658.00, 106 670.00) |

| 40 | 88 | 50 239.50 | (17 949.00, 108 820.00) |

| 41 | 84 | 57 398.00 | (19 243.00, 124 940.00) |

| 42 | 68 | 50 480.00 | (22 547.00, 106 520.00) |

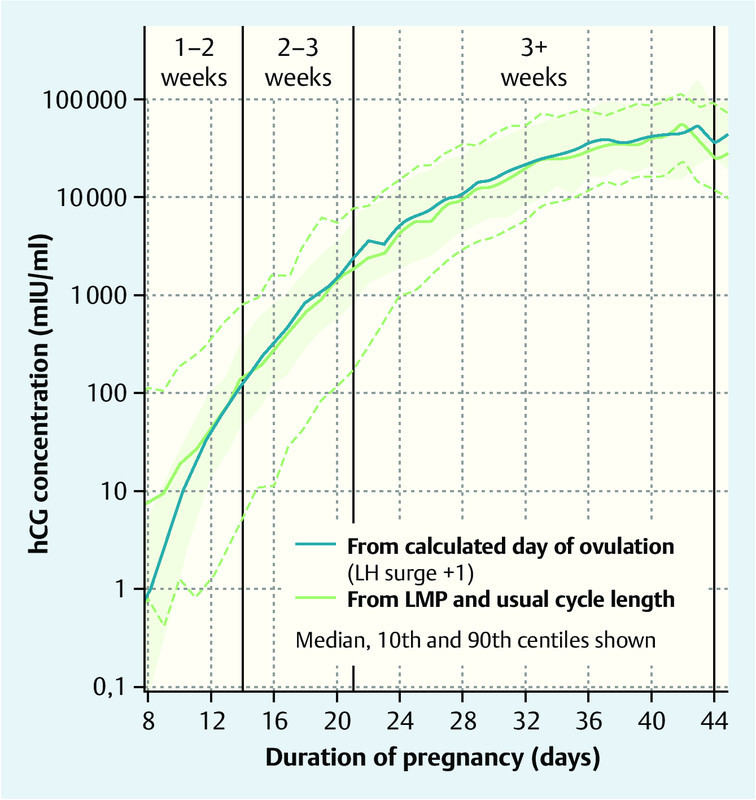

Studies reporting a wide variability in hCG concentrations in early pregnancy have generally calculated pregnancy duration from the day of the last menstrual period (LMP). The variability of hCG concentrations in these studies is unsurprising, given the considerable intra- and inter-individual variation in the length of the follicular phase 17, 20, 21. In addition, inaccuracies frequently occur due to womenʼs poor recollection of their LMP. Studies found that only 32 % of women had regular monthly cycles and were certain of their LMP date 22; higher incidence of round number preferences was also recorded when women were asked the day of their LMP, with the 15th of the month given 2.5 times more often than expected 23. Early pregnancy bleeding, recent hormonal contraceptive use or breastfeeding are all additional reasons why a woman may not have a reliable LMP date. When hCG concentrations are calculated based on the surge in luteinising hormone that stimulates ovulation (LH surge), most of this variability disappears 18. Fig. 2 shows the influence of an imperfect referencing method (LMP) on the precision of the urinary hCG normogram for early pregnancy. This means that semi-quantitative hCG measurement in urine can be useful for determining the true gestational age or, if the time of conception is known, hCG measurement can contribute to early detection of pregnancy disturbances.

Fig. 2.

Impact of reference method used to determine pregnancy duration (day of pregnancy calculated from LMP (− 14 days) or from ovulation (LH surge + 1 day) on variability of urinary hCG in early pregnancy normograms by day. Median hCG levels overlay by day; variability was markedly increased when pregnancy duration was calculated from LMP as opposed to ovulation. The grey area is the 10th to 90th centile band for the US Gestational Age Study 18.

History of Human Chorionic Gonadotropin in Pregnancy Testing

In 1927 the first bioassay for the diagnosis of pregnancy was introduced (Aschheim-Zondek Test). In this test, urine from women in the early stage of pregnancy was injected into immature female mice or rabbits. The ovaries of the animals were examined a few days subsequent to injection for the presence of follicular maturation, luteinisation and haemorrhage into the ovarian stroma, which signified a positive result for the pregnancy test 24. Following the development of an immunoassay in 1959, the first immunological pregnancy test, the Wide-Gemzell test, was developed, using rabbit antibodies against hCG 25. The advent of monoclonal antibodies and the development of enzyme-labelled immunoassays in the 1970s led to more sensitive and accurate hCG assays.

In the wake of these technological innovations, the company Warner-Chilcott launched the first pregnancy test for home use in 1976. This test was not easy to use – it consisted of a test tube and a tube-holder fitted with a special mirror to allow the user to read the results from the bottom of the tube, and it took 2 hours until the results were ready 24.

The home pregnancy tests currently available are quick and easy to use. They consist of an immunometric assay that uses monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies to bind hCG and produce a reaction which results in a colour change. This traditionally occurs with the appearance of marker lines, or in the case of the newer digital tests, the reaction is read by an optical sensor which then displays the result as “Pregnant” or “Not pregnant” (in words) 26.

The most advanced version of the home pregnancy test to date is able to quantify the level of hCG found in urine to provide women with an estimate of the duration of their pregnancy (in weeks since gestation) 17, 27. The Clearblue Digital Pregnancy Test with Conception/Weeks Indicator (SPD Swiss Precision Diagnostics GmbH, Switzerland), measures the level of hCG and categorises the duration of the userʼs pregnancy into 1–2 weeks, 2–3 weeks and 3+ weeks since ovulation/conception, based on established hCG thresholds relative to ovulation, defined as LH surge + 1 day 17, 27.

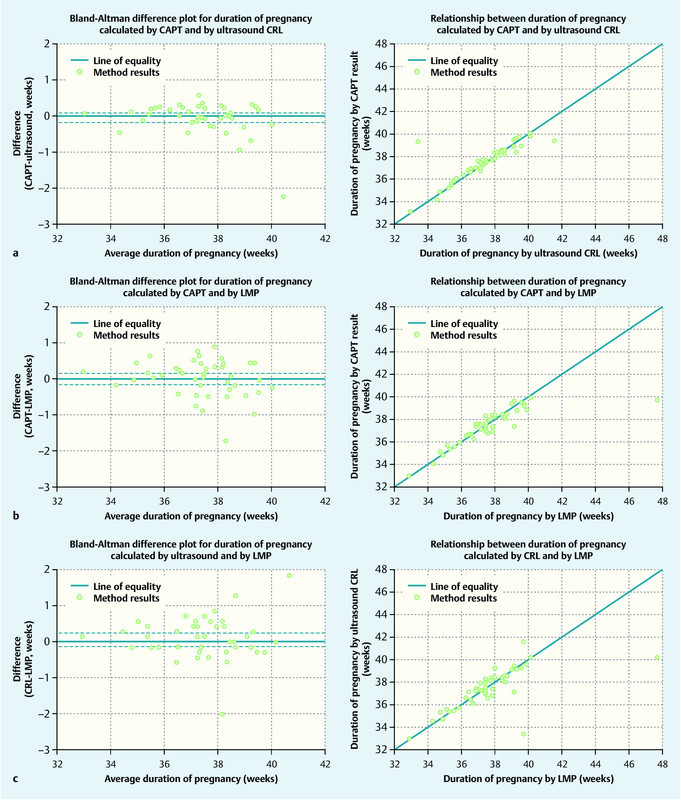

This test operates by using the close relationship between hCG and gestational age. Studies have shown the test results agree well (> 90 %) with the results for gestational age calculated using 11–13 week ultrasound crown rump length (CRL) measurements and pregnancy duration calculated by day of ovulation 27, 28.

This highlights that hCG measurement is a more accurate method for dating early pregnancy than LMP, since LMP provides a value in the same week as the true gestational age for just 46 % of women, within 1 week for 78 % of women and within 2 weeks for 87 % of women 29. Obviously, with hCG being more accurate than LMP to determine pregnancy duration, some women will receive conflicting results. Further investigation on how this affects women would be of interest, but is likely to be similar to cases of divergent results between early ultrasound and LMP.

Most recently, urinary hCG levels in early pregnancy have also been found to correlate with the prospective delivery date. A study comparing the Weeks Indicator test with ultrasound found that the device gave a estimate of time of delivery which was comparable to the CRL estimate based on ultrasound. The mean time from each volunteerʼs device result (weeks since ovulation) to delivery was 37.47 weeks and the mean time from ovulation to delivery based on CRL measurement was 37.40 weeks 30, as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3 a.

to c Relationship between duration of pregnancy assessed using the Clearblue Digital Pregnancy Test with Conception Indicator and a ultrasound and b LMP; c shows the relationship between pregnancy duration assessed by ultrasound and LMP [27]. CAPT: Clearblue Advanced Pregnancy Test with Conception/Weeks Indicator; CRL: crown rump length; LMP: last menstrual period. A Bland-Altman plot of differences is a method to analyse agreement between two different, but highly correlated methods of measurement. The plot investigates the existence of any systematic difference between the clinical measurements. If the mean difference ± 1.96 SE (standard error, dotted line) of the two methods contains zero then the two methods can be used interchangeably.

Analytical Performance of Home Pregnancy Tests

Home pregnancy tests marketed within the USA are required to provide objective evidence of product performance according to specific definitions, notably:

test sensitivity, which is the hCG concentration at which the test would be expected to return positive results > 95 % of the time;

method comparison study, where the device is compared to a predicate device;

pregnancy detection rate when testing is done before the period is due, i.e., the percentage rate of detected pregnant results by day relative to the day of the expected period.

Manufacturers who market tests in both Europe and the USA tend to conform to these definitions across both markets (e.g. Clearblue, First Response, and EPT brands). Device accuracy, which is usually considered to be the percentage of correct detection of negative and positive results (at concentrations of hCG greater than test sensitivity) using urine samples from women seeking to know pregnancy status, are also often calculated. However, it is unclear as to whether other tests available in Germany conform to these definitions and it is therefore not possible to make objective comparisons between tests based on their packaging claims.

Earlier studies have shown that urine pregnancy tests for home use vary greatly in their analytical performance. Cole estimated that a sensitivity of 12.4 mIU/ml is needed to detect 95 % of pregnancies at the time of the expected menstrual period 31. Based on our clinical data, a test must have no false positive results and always be able to detect 25 mIU/ml hCG (the 2nd centile of hCG concentration for this day) to achieve a 99 % accuracy rate from the day of the expected period.

Unfortunately, no recent studies have investigated home pregnancy test performance, and indeed, there are no historical studies evaluating the myriad tests now available on the German market. In the absence of any available data on test performance and the lack of standardisation for evaluating test credentials, any declaration of test accuracy on the package labelling is potentially misleading.

The investigation of claims made about pregnancy tests in Germany found that some made claims consistent with the clinical rise in hCG in early pregnancy. For example, tests claiming 25 mIU/ml sensitivity were declared to be > 99 % accurate from the day of the expected period and capable of detecting pregnancy up to 4 days before the expected period. These tests are likely to be correct, providing the test is always able to detect 25 mIU/ml of hCG in every urine sample. However, other tests are making claims such as “8 days early”, or “can detect 10 mIU/ml”; these claims appear to be inconsistent with both assay performance and the hCG rise observed in early pregnancy. We therefore recently conducted a preliminary evaluation of the most commonly available tests to examine their performance. Nine tests freely available from pharmacies (Clearblue Digital Pregnancy Test with Conception/Weeks Indicator [CBD], Clearblue Plus Pregnancy Test [CBP], Cyclotest [CT], Cyclotest Supersensitive [CSS], MedVec International [MI], Presense [P], Prima Sicher [PS], Testamed Diagnostics Digital [TDD], Testamed Diagnostics Sensitive [TDS]) were tested in triplicate using five hCG standards representing non-pregnant status and stages of early pregnancy (0, 5, 10, 25, 50 mIU/ml). Results were read by a panel of three technicians and all results were photographed for reference. This investigation was designed as a preliminary study which aimed to yield important information for further research.

However, even with a sample size of 3 repetitions per standard, this study found important differences in the laboratory performance of home-based urinary hCG tests (Table 1). Four tests (CBD, CBP, PS, P) were all able to detect 25 mIU/ml, a result that was consistent with their respective manufacturersʼ claimed sensitivity of 25 mIU/ml and ability to test up to 4 days before menstruation is due. TDD had an extremely high error rate of 40 % and was also unable to reliably detect 25 mIU/ml hCG. Although CT has a claimed sensitivity of 25 mIU/ml, it gave negative results for all tested standards. MI and CSS claimed that they were capable of detecting 10 mIU/ml and could be used for testing up to 8 days early, but neither of the tests showed results consistent with these claims. As regards the CT and CSS home pregnancy tests, only one out of six tests was able to detect 50 mIU/ml, and the results suggested that false negative results may be obtained when testing is done early, or on days around the expected period. The data also allowed sample sizes to be calculated for further research on this subject.

The above results clearly show that there needs to be consistency in how manufacturers of pregnancy tests are permitted to describe their testʼs performance, and that certain pregnancy tests currently available may give women misleading results. A more comprehensive study on this subject is urgently needed to corroborate our findings.

Accuracy of Home Pregnancy Tests in Usersʼ Hands

Many home pregnancy tests claim to be more than 99 % accurate 26, when used from the day of the expected period. However, these accuracy figures are determined on the basis of laboratory testing of urine samples carried out by trained laboratory technicians under ideal conditions. The real life accuracy of home-use pregnancy tests may be lower. A review of published studies found that the sensitivity of home-use pregnancy tests declined when subjects performed the test on their own urine compared with the testing of samples done in a laboratory setting 32.

In one study of 27 home-use tests using standard urine samples, 230 of the 478 positive urine samples distributed were wrongly identified as negative by the women testing them. The primary reason for this was considered to be the difficulty women had, regardless of socioeconomic group, in understanding product instructions and, consequently, in reading the test results correctly 33. This conclusion is supported by an evaluation of 16 home-pregnancy test instructions, which found that none of the instructions rated highly when ranked against criteria for compliance with plain language guidelines 34. Some of these errors can be overcome by using newer digital tests, where the result is displayed in words as “Pregnant” or “Not pregnant” and consequently do not give rise to errors based on an erroneous interpretation of the result by the user. Studies have shown that one in four women can misread line-based pregnancy tests, a traditional format whereby the appearance of coloured lines has to be evaluated by the user to determine whether the result is positive or negative 35.

The type of test format is another factor that can influence the accuracy of pregnancy tests when used at home. Home pregnancy tests are available in three main formats: strip, cassette and midstream test sticks. Strip tests have no casing or sample application wick; they therefore require women to collect a urine sample and then dip the small strip-like device into the sample until the urine reaches a prescribed line on the strip. The cassette format requires women to collect a urine sample, following which the user has to add a small quantity of the collected urine to the cassette-like test device using a plastic bulb supplied with the test. Both the strip and cassette test formats were primarily designed to be used by healthcare professionals in a clinical setting. However, they are also available for women to use at home. In contrast, the midstream test stick format was specifically developed to enable women to carry out pregnancy tests easily at home. Midstream test sticks consist of a stick with an absorbent wick at one end, which is placed in the urine stream or dipped into collected urine to obtain a sample.

In a recent study of over 100 women which compared a number of tests with these differing formats, more than 95 % of women stated that they preferred the midstream test stick format 36. The unhygienic nature of the strip and cassette tests together with the difficulties in using the tests due to the multiple steps required were just some of the reasons women stated for their preference. When asked about the cassette test, 23 % of women reported that the cassette test had failed to display a result (either test or control) and only 31 % of women were certain of the result using this test format. In contrast, the strip and midstream test sticks displayed a result in more than 95 % of cases, and women were certain of the test result in 56 % and > 70 % of cases, respectively, for the strip and midstream test stick devices. When women interpreted standard results for urine, using a test done by a trained study coordinator, their reading of the result agreed with that of the coordinator in less than 70 % of cases for cassette and strip test formats, compared with an agreement of more than 99 % when a digital midstream test was evaluated (Table 3) 36. Table 1 shows that pricing does vary between tests, with strips, cassettes and budget tests found to be appreciably less expensive than branded visual tests. The most expensive tests are digital tests. Women purchasing tests may choose to do so based on issues of costs, as well as promised test performance, which gives rise to the question what the cost of an accurate test is.

Table 3 Comparison of results interpreted by volunteers with results interpreted by coordinators for different home pregnancy tests 36.

| Product | Coordinator results | Volunteer results, n | Percentage agreement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnant | Not pregnant | Donʼt know | |||

| a One Step hCG Test (AI DE Diagnostica Co, Ltd, China); b One Step Pregnancy Test (Al DE Diagnostica Co, Ltd, China); c Boots Pharmaceuticals Pregnancy Test (Boots Pharmaceuticals™, UK); d Clearblue COMPACT pregnancy test (SPD Swiss Precision Diagnostics GmbH, Switzerland); e Clearblue PLUS pregnancy test (SPD Swiss Precision Diagnostics GmbH, Switzerland); f Clearblue DIGITAL pregnancy test (SPD Swiss Precision Diagnostics GmbH, Switzerland); * The results were not recorded for 2 pregnant and 2 not pregnant test results. | |||||

| Stripa | Pregnant | 96 | 79 | 48 | 59.1 |

| Not pregnant | 2 | 101 | 7 | ||

| Cassetteb | Pregnant | 120 | 72 | 30 | 69.3 |

| Not pregnant | 0 | 111 | 0 | ||

| Store-brand midstream visualc | Pregnant | 94 | 85 | 37 | 61.2 |

| Not pregnant | 3 | 110 | 4 | ||

| Branded midstream visuald | Pregnant | 142 | 43 | 38 | 75.6 |

| Not pregnant | 0 | 110 | 0 | ||

| Branded midstream easy-use visuale | Pregnant | 214 | 2 | 6 | 97.2 |

| Not pregnant | 1 | 110 | 0 | ||

| Branded midstream digitalf* | Pregnant | 218 | 1 | 0 | 99.3 |

| Not pregnant | 1 | 109 | 0 | ||

Tests are also sold not just in single packs, but as twin or even triplet packs, which offers a more economical option if testing is done more than once. Ideally, a woman should only need to conduct one test, but, as discussed above, if test accuracy is low, a woman may have to test many times during early pregnancy to get a “Pregnant” result. In addition, a look at internet forums shows that many women choose to carry out multiple pregnancy tests because they are desperate to know the result as soon as possible, or wish to confirm a positive result, sometime several times over. An objective assessment of womenʼs pregnancy testing behaviour would be an interesting area for future research.

Other Reasons for Inaccurate Home Pregnancy Test Results

If an accurate test has been used correctly, there are very few occasions when the result may be considered inaccurate. When used correctly, the most common cause of inaccurate test results is if testing is done before there is sufficient hCG present in urine to obtain a positive result. Consequently, women obtain a “Not pregnant” result; if the women test again later in the same cycle, they will obtain a “Pregnant” test result. Errors mostly arise due to inaccurate estimation by women of the day of their expected period 22, 23. Even if women are sure of the day of their LMP, there can be considerable inter-cycle differences in women, as cycles have been observed to vary by more than 13 days in 30 % of women 37. In some instances errors can also be due to a longer than usual time from ovulation to implantation, as this interval has been observed to vary by up to 6 days in naturally conceived pregnancies 38. These types of false negative results thus do not indicate that the test is inaccurate but are rather due to women misunderstanding when the correct time is in their cycle to perform a pregnancy test, or may be due to variations in time to implantation.

Another cause of observed false negative results for home pregnancy tests can be due to unusually high concentrations of hCGβcf, the core fragment of β-hCG, which can occur in later stages of pregnancy 39. Tests recently cleared for marketing in the USA by the Food and Drugs Administration have been required to demonstrate that they do not produce false negative results when used in later pregnancy. European guidelines require manufacturers to do their own risk assessments; however, specific performance requirements are not defined in the directive. More prescriptive European guidelines would be beneficial to ensure that similar risks are taken into consideration by all manufacturers.

False positive results have been reported when devices have been tested on samples from peri- and post-menopausal women 40. In this study, Snyder et al. calculated that a very sensitive test (5 mIU/ml) would generate no false positive results in women aged 18–40 where the highest hCG value seen was 4.6 mIU/ml. However, 1.3 % of results seen in women aged 41–55, where the maximum hCG seen was 7.7 mIU/ml, would be false positives, and 6.7 % of results in women over 55 years old would be false positives (the highest hCG seen was 13.1 mIU/ml). Oral contraceptive pill (OCP) use is common in peri-menopausal women. Therefore, secondary amenorrhoea after stopping OCP can prompt women to use home pregnancy tests during peri-menopause, as can the irregular periods often encountered in peri-menopause. If the sensitivity level of pregnancy tests were set at concentrations of 15 mIU/ml hCG or above, there would be no specificity issue; this means that the specificity of hCG of high sensitivity tests to detect pregnancy is reduced, albeit only to a small extent and only for the peri- and post-menopausal cohort.

Other less common reasons for misleading results of home-based pregnancy test include the use of fertility drugs containing hCG (such as Pregnyl®, Ovitrelle® and Predalon® for ovulation induction or luteal phase support) which, if testing is done too soon after administration, may give a false “Pregnant” result. The presence of very rare malignancies (e.g. choriocarcinoma, ovarian neoplasm) can also create misleading results.

Discussion

Home pregnancy tests are the most common diagnostic assays used by patients at home and in a clinical setting. There may be serious consequences if false negative or false positive results are displayed, e.g., an unintended pregnancy in a young woman. In the USA, strict criteria and definitions are in place to ensure that the performance of all marketed tests is satisfactory. In Germany and other European countries, assessment is done via a notified body accredited by competent authorities of EU member states. Although notified bodies are capable of performing conformity assessments to award CE marking in accordance with the New Approach directives, these assessments are not based on common definitions. It would therefore be particularly welcome if a set of common definitions and testing requirements was established. This is especially important for medical professionals where it is necessary to be informed about the diagnostic potential, accuracy, and possible limitations of home pregnancy tests to be able to advise patients appropriately.

With clinically sensitive urinary pregnancy tests, it is possible to detect pregnancy up to 4 days before the expected period. However, not all commonly sold home pregnancy tests offer the promised clinical sensitivity. About 50 % of investigated pregnancy tests currently for sale in Germany did not show the sensitivity claimed on the testʼs package insert. The results of our preliminary study show that tests which made extreme claims, especially claims about high sensitivity and early detection, should be used with caution, as these tests are very unlikely to live up to their claimed performance. However, tests that have been subjected to the rigor of an FDA review do appear to meet their performance claims, highlighting the importance of requiring appropriate performance standards for home pregnancy tests.

Urinary hCG shows a remarkable uniformity in its rise during early pregnancy. Particularly if hCG concentrations are referenced to the time of ovulation or conception, the high variability of hCG concentrations reported for early pregnancy in some studies disappears. Dating the gestational age based on the LMP is very unreliable. Irregular cycles, early pregnancy bleedings, previous use of hormonal contraceptives or breastfeeding are common causes which can obscure the time of conception and the gestational age. Since reliable normograms of urinary hCG concentrations already exist, the logical consequence is the development of semi-quantitative hCG home assays. Prospective studies have revealed the high accuracy of currently available semi-quantitative home pregnancy tests. The studies have shown that semi-quantitative hCG measurement in urine is helpful to determine gestational age. This is important in the clinical setting when ultrasound scans are performed early after a first positive pregnancy test. Uncertainty results if the pregnancy cannot be visualised on ultrasound or the scan does not correspond to the calculated gestational age based on LMP. A first ultrasound scan at week 8 + 0–11 + 6 may be relatively late from a clinical point of view and will not be accepted by many of the patients. If time of conception is known, semi-quantitative hCG measurement in urine could be helpful to detect disturbances of early pregnancy or is an early sign of multiple pregnancy. Future investigations into how this affects women would be of interest and could show that early semi-quantitative pregnancy tests give more certainty to patients and physicians.

The reliability of pregnancy test results is not only based on the biochemical performance of the test system. Other important factors are test handling, test procedures and, last but not least, an easy-to-understand instruction leaflet. The digital display of results (“Pregnant”, “Not pregnant”) has removed the need for users to interpret the result, removing errors of interpretation as a cause of incorrect results. These technological advances in home pregnancy testing mean that accurate and reliable results are within reach.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Christian Gnoth: Principle investigator of clinical studies on the performance of fertility monitors, partly supported by SPD (Swiss Precision Diagnostics) Development Company Ltd. Sarah Johnson: Employee of SPD Development Company Limited, a fully owned subsidiary of SPD (Swiss Precision Diagnostics) Development Company Ltd., the manufacturers of “Clearblue pregnancy and fertility tests”.

References

- 1.Richtlinie 98/79/EG des Europäischen Parlaments und Rates vom 27. Oktober 1998 über In-vitro-Diagnostika, Anhang III

- 2.Öko-Test, Ratgeber Gesundheit und Fitness 8/2008

- 3.Birken S, Berger P, Bidart J-M. et al. Preparation and characterisation of new WHO standards for human chorionic gonadotropin and metabolites. Clin Chem. 2003;49:144–154. doi: 10.1373/49.1.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bristow A, Berger P, Bidart J. et al. Establishment, value assignment, and characterization of new WHO reference reagents for six molecular forms of human chorionic gonadotropin. Clin Chem. 2005;51:177–182. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.038679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sturgeon C M, Berger P, Bidart J. et al. Differences in recognition of the 1st WHO international reference reagents for hCG-related isoforms by diagnostic immunoassays for human chorionic gonadotropin. Clin Chem. 2009;55:1484–1491. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.124578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alfthan H, Stenman U-H. Pregnancy serum contains the core fragment of human chroriogonadotropin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;70:783–787. doi: 10.1210/jcem-70-3-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole L A, Kardana A, Ying F C. et al. The biological and clinical significance of nicks in human chorionic gonadotropin and its free beta-subunit. Yale J Biol Med. 1991;64:627–637. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McChesney R, Wilcox A J, OʼConnor J F. et al. Intact HCG, free HCG beta subunit and HCG beta core fragment: longitudinal patterns in urine during early pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:928–935. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kovalevskaya G, Birken S, Kakuma T. et al. Early pregnancy human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) isoforms measured by an immunometric assay for choriocarcinoma-like hCG. J Endocrinol. 1999;161:99–106. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1610099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kovalevskaya G, Kakuma T, Schlatterer J. et al. Hyperglycosylated hCG expression in pregnancy: cellular origin and clinical applications. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;260:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler S A, Khanlian S A, Cole L A. Detection of early pregnancy forms of human chorionic gonadotropin by home pregnancy test devices. Clin Chem. 2001;47:2131–2136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whittington J, Fantz C R, Gronowski A M. et al. The analytical specificity of human chorionic gonadotropin assays determined using WHO International Reference Reagents. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stewart B K, Nazar-Stewart V, Tiovola B. Biochemical discrimination of pathologic pregnancy from early, normal intrauterine gestation in symptomatic patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995;103:386–390. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/103.4.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zegers-Hochschild F, Altierl E, Fabres C. et al. Predictive value of human chorionic gonadotrophin in the outcome of early pregnancy after in-vitro fertilization and spontaneous conception. Hum Rep. 1994;9:1550–1555. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnhart K T, Sammel M D, Rinaudo P F. et al. Symptomatic patients with an early viable intrauterine pregnancy: hCG curves redefined. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:50–55. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000128174.48843.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norman R J, Menabawey M, Lowings C. et al. Relationship between blood and urinary concentrations of intact human chorionic gonadotropin and its free subunits in early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;69:590–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson S R, Miro F, Barrett S. et al. Levels of urinary human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) following conception and variability of menstrual cycle length in a cohort of women attempting to conceive. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:741–748. doi: 10.1185/03007990902743935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larsen J, Buchanan P, Johnson S. et al. Human chorionic gonadotropin as a measure of pregnancy duration. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;123:189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eskild A, Fedorcsak P, Mørkrid L. et al. Maternal body mass index and serum concentrations of human chorionic gonadotropin in very early pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:905–910. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lenton E A, Landgren B M, Sexton L. et al. Normal variation in the length of the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle: effect of chronological age. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1984;91:681–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1984.tb04830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Creinin M D, Keverline S, Meyn L A. How regular is regular? An analysis of menstrual cycle regularity. Contraception. 2004;70:289–292. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geirsson R T, Busby-Earle R M. Certain dates may not provide a reliable estimate of gestational age. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;98:108–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1991.tb10323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waller D K, Spears W D, Gu Y. et al. Assessing number-specific error in the recall of onset of last menstrual period. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2000;14:262–267. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2000.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haarburger D, Pillay T S. Historical perspectives in diagnostic clinical pathology: development of the pregnancy test. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:546–548. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2011.090332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wide L, Gemzell C A. An immunological pregnancy test. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1960;35:261–267. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.xxxv0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scolaro K L, Braxton-Lloyd K, Helms K L. Devices for home evaluation of womenʼs health concerns. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65:299–314. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson S R, Godbert S, Perry P. et al. Accuracy of a home-based device for giving an early estimate of pregnancy duration compared with reference methods. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:1635–1641. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson S, Shaw R, Parkinson P. Home pregnancy test compared to standard-of-care ultrasound dating in the assessment of pregnancy duration. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:393–401. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.545378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mustafa G, David R J. Comparative accuracy of clinical estimate versus menstrual gestational age in computerized birth certificates. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:15–21. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson S, Godbert S. Comparison of home pregnancy test with weeks estimator and ultrasound crown rump measurement to predict delivery date. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(3 Suppl.):S330. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cole L A, Khanlian S, Sutton J. et al. Accuracy of home pregnancy tests at the time of missed menses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:100–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bastian L A, Nanda K, Hasselblad V. et al. Diagnostic efficiency of home pregnancy test kits: a meta-analysis. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:465–469. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.5.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daviaud J, Fournet D, Ballonque C. et al. Reliability and feasibility of home-use tests: laboratory validation and diagnostic evaluation by 638 volunteers. Clin Chem. 1993;39:53–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallace L S, Zite N B, Homewood V J. Making sense of home pregnancy test instructions. J Womens Health. 2009;18:363–368. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.0985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomlinson C, Marshall J, Ellis J E. Comparison of accuracy and certainty of results of six home pregnancy tests available over-the-counter. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:1645–1649. doi: 10.1185/03007990802120572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pike J, Godbert S, Johnson S. Comparison of volunteersʼ experience of using, and accuracy of reading, different types of home pregnancy test formats. Expert Opin Med Diagn. 2013;7:435–441. doi: 10.1517/17530059.2013.830103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geirsson R T. Ultrasound instead of last menstrual period as the basis of gestational age assignment. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1991;1:212–219. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1991.01030212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilcox A J, Baird D D, Weinberg C R. Time of implantation of the conceptus and loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1796–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906103402304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gronowski A M, Cervinski M, Stenman U. et al. False-negative results in point-of-care qualitative human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) devices due to excess hCG-beta core fragment. Clin Chem. 2009;55:1389–1394. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.121210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Snyder J A, Haymond S, Parvin C A. et al. Diagnostic considerations in the measurement of human chorionic gonadotropin in aging women. Clin Chem. 2005;51:1830–1835. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.053595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]