Abstract

A novel mutation in the α-Synuclein (α-Syn) gene “G51D” was recently identified in two familial cases exhibiting features of Parkinson's disease (PD) and multiple system atrophy (MSA). In this study, we explored the impact of this novel mutation on the aggregation, cellular and biophysical properties of α-Syn, in an attempt to unravel how this mutant contributes to PD/MSA. Our results show that the G51D mutation significantly attenuates α-Syn aggregation in vitro. Moreover, it disrupts local helix formation in the presence of SDS, decreases binding to lipid vesicles C-terminal to the site of mutation and severely inhibits helical folding in the presence of acidic vesicles. When expressed in yeast, α-SynG51D behaves similarly to α-SynA30P, as both exhibit impaired membrane association, form few inclusions and are non-toxic. In contrast, enhanced secreted and nuclear levels of the G51D mutant were observed in mammalian cells, as well as in primary neurons, where α-SynG51D was enriched in the nuclear compartment, was hyper-phosphorylated at S129 and exacerbated α-Syn-induced mitochondrial fragmentation. Finally, post-mortem human brain tissues of α-SynG51D cases were examined, and revealed only partial colocalization with nuclear membrane markers, probably due to post-mortem tissue delay and fixation. These findings suggest that the PD-linked mutations may cause neurodegeneration via different mechanisms, some of which may be independent of α-Syn aggregation.

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson's disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder characterized by severe loss of dopamine producing neurons in the substantia nigra of the brain. The presence of intracellular inclusions termed “Lewy bodies” comprising misfolded and aggregated proteins within surviving neurons has been long established as a neuropathological hallmark of PD (1). The discovery that mutations in the α-Synuclein (α-Syn) encoding gene “SNCA” cause autosomal dominant familial PD two decades ago (2) led to the identification of the α-Syn protein as the major component of Lewy bodies (3).

α-Syn is a natively unfolded presynaptic protein that is involved in regulating neurotransmitter release, synaptic plasticity and intracellular trafficking within the ER/golgi network (4,5). Although α-Syn exhibits no stable secondary structure in solution (6), it adopts an α-helical conformation upon interaction with unilamellar vesicles comprising negatively charged lipids (7–10). Moreover, upon aggregation, α-Syn undergoes structural changes, self-associates and forms β-sheet rich oligomeric species and amyloid fibrils (11).

Duplications/triplications (12,13) and several missense point mutations of the SNCA gene have been identified in patients having a familial history of PD, namely A53T, A30P and E46K (2,14,15). Recently, two new familial mutations in α-Syn's coding sequence were discovered at residues H50Q and G51D (16–18). Whereas the former was linked to late-onset PD, the G51D mutation was associated with early onset of disease and neuropathological features of both PD and multiple system atrophy (MSA); an α-synucleinopathy showing glial cytoplasmic inclusions (GCIs) in oligodendrocytes in addition to neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions. Interestingly, these two mutations showed different effects on α-Syn aggregation in vitro, with the H50Q slightly enhancing aggregation (19), and the G51D mutant (α-SynG51D) exhibiting slower oligomerization propensity compared to the WT protein (α-SynWT) (18). Nevertheless, the precise mechanism by which the G51D mutation causes PD/MSA remains unknown.

In this study, we performed detailed studies to examine the effect of the G51D mutation on the structure, aggregation, membrane binding and phosphorylation of α-Syn, both in vitro and in cells. In addition, we investigated the impact of this mutation on α-Syn's subcellular localization, secretion and toxicity using different mammalian cell lines and primary neurons. Finally, we extended our analysis to post-mortem human brain samples of α-SynG51D cases, where we performed thorough immunohistochemical analysis of the subcellular localization of α-SynG51D. Our results suggest that, unlike other PD-linked mutations which have been shown to enhance α-Syn oligomerization and/or fibril formation, the G51D mutant aggregates significantly slower than α-SynWT in vitro, and forms amorphous aggregates at early aggregation stages. In addition, the G51D mutant exhibits impaired membrane binding in vitro and in yeast, is secreted more rapidly by mammalian cells and is enriched in the nuclear compartment of cell lines and primary neurons; an effect that is concomitant with enhanced nuclear S129 phosphorylation and exacerbated mitochondrial fragmentation. Notably, we could not detect any nuclear α-SynG51D in post-mortem human brains, probably due to the post-mortem delay and/or tissue fixation and processing procedures.

RESULTS

The G51D mutation does not significantly affect the structure of free α-Syn in aqueous buffer

We first assessed whether the G51D mutation influences the native structure of α-Syn in vitro. After showing that the two proteins run as a single band on SDS–PAGE, exhibit the same random coil secondary structure signal (as shown by circular dichroism spectroscopy; CD) and behave as monomeric proteins (as determined by MALS; Supplementary Material, Fig. S1A–E), we examined the structure of α-SynG51D in aqueous solution compared to α-SynWT using NMR spectroscopy. The 1H,15N-HSQC spectrum of the mutant appeared to be very similar to that of α-SynWT and a comparison of amide group chemical shifts (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1F) confirmed that differences in spectra are localized to the few (±5) residues surrounding the mutation site, although small chemical shift perturbations extend slightly further C-terminal to the mutation site. Analysis of the secondary structure propensity of α-SynG51D via alpha-carbon secondary shifts (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1G) showed no significant loss or gain of secondary structure compared to α-SynWT, despite some small perturbations at the mutation site. These data show that the G51D mutation does not significantly affect the overall disordered structure of α-Syn in aqueous solution. The G51D mutation also does not significantly perturb transient long-range N- to C-terminal contacts known to occur in α-SynWT (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1H).

The G51D mutation attenuates α-Syn aggregation and alters the structure of α-Syn aggregates in vitro

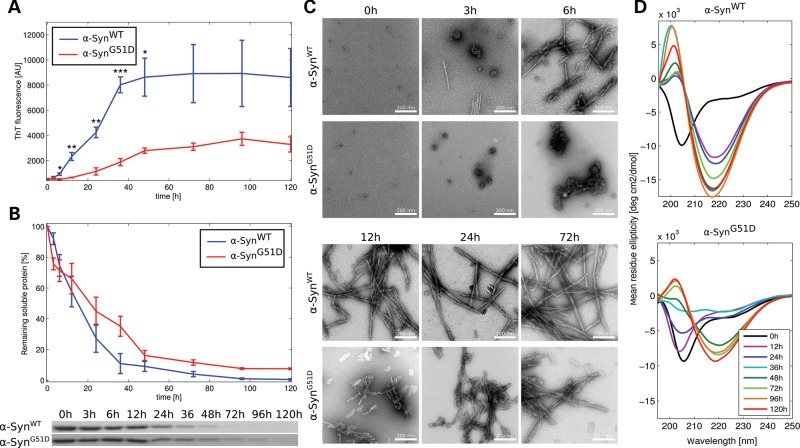

In order to compare the kinetics of aggregation of α-SynWT versus α-SynG51D, we performed in vitro aggregation experiments by incubating each of the proteins for several days at 37°C under shaking conditions. Strikingly, and as presented in Figure 1, the aggregation of the G51D mutant was significantly slower than that of the WT protein. α-SynWT showed an increase in Thioflavin-T (ThT) signal already after 3–6 h incubation, and the plateau was reached after ∼36 h (Fig. 1A), whereas the ThT signal of the G51D mutant began to increase only after 12 h of incubation and the plateau was reached after 48 h. Moreover, the final absolute value of the plateau ThT signal of the G51D mutant was consistently about two to three times less than that of α-SynWT. As a second readout to assess fibril formation, we used a sedimentation assay which allows quantifying the loss of soluble protein as a function of time. In line with our ThT data, the sedimentation assay showed that α-SynWT converted to insoluble aggregates slightly faster than the G51D mutant (Fig. 1B). Although there was no soluble protein left after 72 h of incubation of α-SynWT, soluble α-SynG51D was still observed after 120 h of incubation. However, the difference in aggregation propensity observed using this assay was not as prominent as shown by ThT.

Figure 1.

The G51D mutation attenuates α-Syn aggregation in vitro. Recombinant α-SynWT or α-SynG51D were incubated at 37°C under shaking conditions, and the kinetics of aggregation of both proteins were followed by: (A) ThT ± SEM (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n = 3), (B) quantification of remaining soluble protein ± SEM (the differences between the WT and mutant are non-significant, for all time points, n = 3), (C) transmission electron microscopy (scale bar is 200 nm) and (D) circular dichroism. In all used assays, we observed attenuation of α-SynG51D aggregation kinetics compared to α-SynWT.

TEM micrographs revealed that although small oligomeric species were observed for both proteins at early time points, after 3 h of incubation those species readily converted into fibrils in the case of α-SynWT, but not for α-SynG51D, which continued to form larger amorphous aggregates (Fig. 1C). In fact, fibrils of the G51D mutant were first observed only after 24 h of incubation. The large ThT-negative amorphous aggregates observed with the G51D mutant are likely to precipitate when centrifuged (i.e. leading to loss of soluble protein) which could explain why the G51D mutant exhibited longer fibrilization lag phase by ThT, despite having comparable loss of soluble species in the sedimentation assay. Notably though, at longer incubation times these amorphous aggregates seem to convert into fibrils, as they are no longer observed by TEM, and very little α-Syn remains in the soluble fraction. Consistent with the faster aggregation rate of the WT protein, however, CD spectroscopy showed that while the secondary structure of α-SynWT was converted from random coil to β-sheet conformation within the first 12 h of incubation, α-SynG51D conversion to β-sheets was delayed and completed only after 48 h (Fig. 1D).

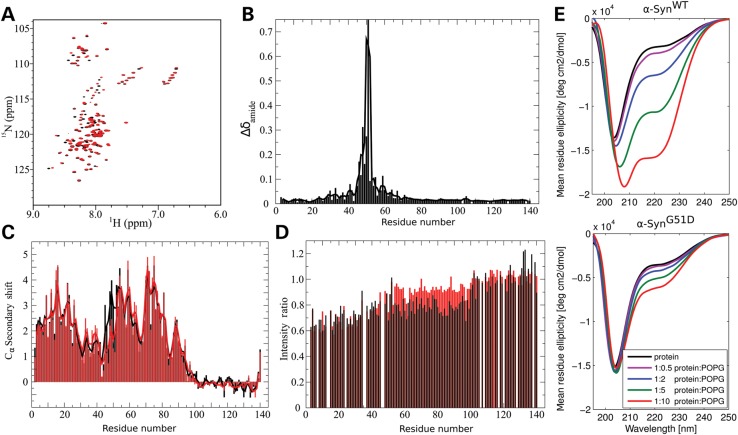

The G51D mutation disrupts local helix formation in the presence of SDS and decreases binding to lipid vesicles C-terminal to the mutation site

The G51 residue lies within the N-terminal region of α-Syn which mediates α-helix formation upon interaction with acidic vesicles. Therefore, we investigated the effect of the G51D mutation on α-Syn lipid interaction by NMR and CD spectroscopy. As previously established, α-SynWT adopts a broken-helix structure in the presence of spheroidal SDS micelles in which the N-terminal ∼100 residues form two antiparallel helices (helix-1 and helix-2) connected by a short linker (10,20–22). Comparison of 1H,15N-HSQC spectra of α-SynWT and α-SynG51D in the presence of 40 mm SDS shows significant spectral changes (Fig. 2A) and a residue-by-residue comparison of amide group chemical shifts (Fig. 2B) reveals that differences are not only centered on the mutation site but extend ∼15 residues both N- and C-terminal to the position of the mutation. Analysis of the alpha-carbon secondary shifts (Fig. 2C) shows that residues 45–55, corresponding to the N-terminal end of helix-2, exhibit decreased helicity in the G51D mutant, which may reflect N-terminal fraying of helix-2 in the presence of the glycine to aspartate mutation.

Figure 2.

The G51D mutation disrupts local helix formation in the presence of SDS, decreases binding to lipid vesicles C-terminal to the site of mutation and severely inhibits helical folding in the presence of acidic vesicles. (A) 1H,15N-HSQC spectra of α-SynWT (black) and α-SynG51D (red) in 40 mm SDS. (B) Plot of averaged amide chemical shift difference [Δδamide = √(½(ΔδHN2 + (ΔδN/5)2))] between the SDS-bound α-SynWT and α-SynG51D spectra as a function of residue number. The line shows a three-residue average. (C) Plot of alpha-carbon secondary shifts (difference between measured chemical shift and random coil chemical shift) for α-SynWT (black) and α-SynG51D (red) in the presence of 40 mm SDS as a function of residue number. The lines show three-residue averages. (D) Plot of the ratio of amide cross-peak intensity in samples with 3 mm SUVs to the intensity in samples without SUVs for ∼150 µm α-SynWT (black) and α-SynG51D (red) by residue number. (E) Circular dichroism of α-SynWT and α-SynG51D mixed with protein:lipid weight ratios of 1:0, 1:0.5, 1:2, 1:5 and 1:10. α-SynG51D (lower panel) shows lower lipid biding propensity compared with α-SynWT (upper panel), as evidenced by the drastic decrease in alpha helical content at all tested ratios.

NMR spectroscopy was also used to examine the effect of the G51D mutation on α-Syn binding to lipid vesicles in a residue-specific manner, taking advantage of the fact that α-Syn residues participating in binding become NMR-invisible (23,24). Thus, in a partial-binding regime, the intensity decrease of amide cross-peaks in the presence of vesicles can report on the lipid-bound population of that particular region of the protein. When incubated with 20:1 lipid:protein small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) composed of 15:25:60 DOPS:DOPE:DOPC, α-SynG51D shows a qualitatively similar binding profile to that of α-SynWT (Fig. 2D), with the N-terminal ∼100 residues showing decreased intensity resulting from binding. However, the decrease in intensity for residues ∼45–100 is notably less for the mutant protein. Interestingly, this region corresponds roughly to helix-2 of the broken-helix form of α-Syn.

Next, we compared the ability of α-SynWT versus α-SynG51D to form α-helical structure upon interaction with different ratios of negatively charged POPG vesicles (1:0, 1:0.5, 1:2, 1:5 and 1:10, w/w) by CD. As previously reported (7,8), we observed an increase in α-SynWT α-helical content with increasing POPG proportions (Fig. 2E). Strikingly, the G51D mutant exhibited significantly reduced propensity to form α-helices in the presence of vesicles, even at high POPG ratios. The capacity of α-SynG51D to form α-helices was further investigated using trifluoroethanol (TFE), a solvent that favors helix formation of intrinsically helical motifs. As such, comparing CD spectra of α-SynG51D mixed with POPG vesicles or with TFE enables us to differentiate between the intrinsic helical propensity of α-SynG51D and conformational changes induced by its interaction with acidic vesicles, which correlate with biological activity (25). The inherent capacity of α-SynG51D to form α-helices was not abrogated, as demonstrated by the fact that it can still adopt an α-helical conformation in the presence of TFE (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2A), hence demonstrating that the G51D mutation interferes specifically with α-Syn interaction with negatively charged vesicles.

Partially folded conformations of α-Syn in the presence of intermediate protein to lipid ratios have been reported to favor membrane-induced aggregation (24,26–28), while the strong α-helical conformation of the protein observed in high excess of lipids was shown to inhibit the aggregation process. As such, and since G51D shows partially folded states even in excess of lipids, we hypothesized that membrane-driven aggregation should be favored at all protein to lipids ratios. To test this hypothesis, we incubated α-SynWT and α-SynG51D with different ratios of POPG vesicles (1:0, 1:0.5, 1:2, 1:5 and 1:10, w/w) under shaking conditions. As previously reported (29,30), we observed that α-SynWT aggregation is favored in the presence of intermediate protein to lipid ratios, while it is inhibited at high ratios, due to the strong α-helical conformation (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2B). Conversely, α-SynG51D which only forms partially folded states even in excess of lipids, aggregation was enhanced at all tested ratios.

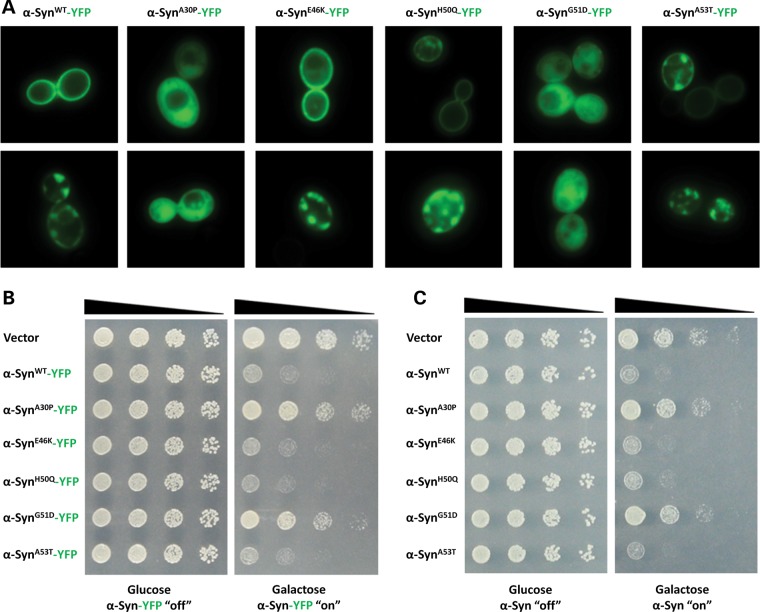

The G51D mutation impairs membrane association, inclusion formation and toxicity of α-Syn in yeast

After having shown that the G51D substitution attenuates α-Syn aggregation and membrane binding in vitro, we sought to investigate whether this mutation influences the cellular properties of α-Syn. Yeast cells have been used to model α-Syn biology and pathobiology, to define mechanisms of aggregation and toxicity, as well as to discover small molecule suppressors of α-Syn-induced toxicity (31–37). Therefore, we first compared the localization of the G51D mutant to that of α-SynWT, as well as to the other PD-linked mutations, in yeast cells. To assess this, C-terminally YFP-tagged proteins were expressed and visualized by live fluorescence microscopy (34). Strikingly, whereas WT, E46K, H50Q and A53T α-Syn localized to the plasma membrane or formed cytoplasmic vesicular membrane accumulations, both the A30P and G51D mutants exhibited impaired membrane association (Fig. 3A). Moreover, the vast majority of cells expressing α-SynG51D or α-SynA30P did not form vesicular α-Syn foci but showed mostly diffuse cytoplasmic localization (Fig. 3A). To assess the effect of the impaired membrane binding on yeast viability, serial dilutions of yeast transformants expressing WT or mutant α-Syn fused to YFP were spotted on glucose- or galactose-containing agar plates, and growth was assessed after 2 days. Whereas all transformants grew equally well on the control glucose plates (no α-Syn expression), induction of expression in galactose-containing agar plates inhibited the growth of yeast cells expressing WT, E46K, H50Q or A53T α-Syn but not the G51D or A30P mutants (Fig. 3B). Importantly, spotting assays performed with untagged α-Syn and mutants showed similar results, indicating that the YFP-tag does not affect toxicity in this model (Fig. 3C). Together, these results suggest that the ability to associate with membranes is a component of α-Syn toxicity in yeast.

Figure 3.

The G51D mutation impairs α-Syn membrane binding, inclusion formation and toxicity in yeast. (A) Fluorescence microscopy was used to visualize the localization of C-terminally YFP-tagged α-Syn fusion proteins expressed from a high-copy plasmid. Representative examples of localization patterns are shown in top and bottom panels for each construct. Whereas WT, E46K, H50Q and A53T α-Syn localized to the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic vesicular membrane accumulations, the A30P and G51D mutations impaired α-Syn membrane association and exhibited mostly diffuse cytoplasmic distribution. (B) Serial dilutions of yeast transformants expressing WT or mutant α-Syn YFP fusions were spotted on glucose- or galactose-containing agar plates, and growth was assessed after 2 days. Whereas the transformants grew equally well on the control glucose plates (no α-Syn expression), expression of WT, E46K, H50Q or A53T α-Syn inhibited growth and the A30P and G51D mutations did not. (C) Spotting assay using untagged α-Syn constructs demonstrates similar results as with the YFP-tagged constructs shown in (B).

The G51D mutation enhances the nuclear localization of α-Syn in mammalian cells and primary neurons

We next investigated whether the G51D mutation influences the properties of α-Syn in mammalian cells. First, we examined the ability of WT versus mutant α-Syn to bind cellular membranes in HEK cells by assessing colocalization with co-transfected Mb-YFP (containing a palmitoylation domain of neuromodulin that targets YFP to membranes) or ER-DsRed (containing targeting sequence of calreticulin “KDEL retrieval sequence” that targets DsRed to the ER). As a control, we performed the same assay with α-SynA30P which showed impaired membrane binding in our yeast model, and has been consistently reported to exhibit reduced binding to lipids in vitro as well as in cells (38–40). Immuno-labeling using the Syn-211 antibody showed that all three variants exhibit mostly cytosolic localization, and that neither the G51D nor A30P mutations perturb the partial colocalization of α-Syn with Mb-YFP or ER-DsRed (Fig. 4A), indicating that this assay may not have the discriminatory strength to distinguish differences in membrane binding of the three variants. Strikingly though, biochemical fractionation of HEK cells expressing WT or mutant α-Syn showed significant enrichment of α-SynG51D in the nuclear fraction compared with WT or the A30P mutant (Fig. 4B). In order to investigate this finding by immunocytochemistry, we performed a thorough assessment of the subcellular localization of α-SynWT and α-SynG51D using different anti-α-Syn antibodies (epitopes depicted in Supplementary Material, Fig. S3B) in transiently transfected HEK cells. Whereas the three antibodies FL-140, Syn-208 and Syn-211 detected mainly cytosolic distribution of α-Syn without detectable signal in the nucleus (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3A), the Syn-1, EP1646Y and SA-3400 antibodies detected additional nuclear signal in some α-Syn expressing cells that was comparable in intensity to that in the cytosol (Fig. 4C and Supplementary Material, Fig. S3A). Importantly, more cells showing nuclear α-Syn signal with the Syn-1 antibody were detected in HEK cells expressing α-SynG51D compared to α-SynWT (Fig. 4C), hence confirming our biochemical fractionation data.

Figure 4.

Effect of the G51D mutation on α-Syn subcellular localization in mammalian cells and primary neurons. (A) Immunocytochemical analysis using the Syn-211 antibody shows only partial colocalization of α-SynWT, α-SynG51D and α-SynA30P with the co-expressed cytoplasmic membrane marker (Mb-YFP; upper panel) or endoplasmic reticulum marker (ER-DsRed; lower panel). (B) Subcellular fractionation of HEK cells expressing α-SynWT, α-SynG51D or α-SynA30P reveals enriched localization of the G51D mutant in nuclear fractions compared with α-SynWT and α-SynA30P (upper panel). The total (input) and cytosolic fractions establish that similar levels of α-Syn are expressed, and probing with HSP-90 and Parp-1 demonstrates equal loading, as well as purity of cytosolic versus nuclear fractions, respectively. Densitometric quantification (lower panel, n = 3) of α-Syn in nuclear fractions shows significant (P < 0.05) increase in α-SynG51D enrichment in nuclear fractions compared to α-SynWT. (C) Immunocytochemical analysis using the Syn-1 antibody shows that cells expressing α-SynWT or α-SynG51D exhibit either pure cytoplasmic localization, or cytoplasmic with additional comparable nuclear signal of α-Syn (upper panel). The lower panel shows quantification of cells expressing α-SynWT or α-SynG51D and manifesting either of the two distributions. At least 800 cells per condition were quantified from four independent coverslips (transfections), and the whole experiment was repeated twice. The asterisk represents significance at P < 0.05. (D) Living HEK cells expressing mEOS2-α-SynWT or mEOS2-α-SynG51D were repeatedly photoconverted using a 461 nm laser in the cytosol (crossed circles), and imaged by time-lapse confocal microscopy. The upper and lower panels for each condition show cellular fluorescence (488 and 568 nm) before (t = 0) or after photoconversion (t = ∼5 min), respectively. Note that the photoconversion caused the bleaching of the cytosolic 488 nm signal. Scale bar denotes 2 μm. (E) Fluorescence intensity curves of nuclear photoactivated WT or G51D mEOS2-α-Syn in cells photoconverted in the cytosol. For each condition, at least 25 cells were analyzed, and the experiment was repeated twice. Each plot represents mean ± SD for each time point of all photoactivation experiments. (F) Immunocytochemical analysis of neurons using the N-19 antibody shows that both α-SynWT and α-SynG51D are localized in neuronal soma and neurites (left panel, low magnification), as evidenced by the co-staining with MAP-2. High magnification images of soma (right panels) show that neurons expressing α-SynG51D exhibit more nuclear localization compared to α-SynWT. (G) Intensity profiles of α-Syn and DAPI staining along red lines in (F) shows increased basal levels of α-SynG51D in neuronal nuclei compared to α-SynWT expressing neurons.

To further investigate the increase in nuclear α-SynG51D levels, we utilized the photoconvertable fluorescent protein “mEOS2” (41). Normally, this protein emits bright green fluorescence at 506 nm. However, if illuminated at near-ultraviolet wavelengths, its fluorescence is photoconverted to orange–red (584 nm), hence allowing specific photoconversion and tracking of mEOS2 tagged proteins. Therefore, we expressed constructs encoding α-SynWT or α-SynG51D that are N- or C-terminally fused to mEOS2 in HEK cells. At steady state, all proteins showed cytosolic and nuclear localization (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3C). Upon repeated photoconversion in a specific region in the cytosol however, time-lapse confocal imaging showed that photoconverted mEOS2-α-SynG51D is translocated to the nucleus faster than its WT counterpart (Fig. 4D and Supplementary Material, Videos S1 and S2). Quantification of the intensities of photoconverted proteins in the nuclei of 25 cells per condition further revealed that mEOS2-α-SynG51D is translocated at a higher rate compared with mEOS2-α-SynWT (Fig. 4E). Notably though, the effect of the G51D mutation on nuclear transport was much less pronounced when the C-terminal mEOS2 fusion proteins were used to monitor nuclear translocation (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3D). This observation could be explained by previous studies implicating the C-terminal domain in regulating the nuclear localization of α-Syn (42–44).

To determine whether the G51D mutation affects the subcellular localization of α-Syn in neurons, we transiently transfected primary hippocampal neurons and compared the localization of α-SynWT and α-SynG51D using the different α-Syn antibodies summarized in Figure S3B. All tested antibodies detected α-Syn with in neuronal soma and neurites (Fig. 4F and Supplementary Material, Fig. S4). Neuronal expression of α-Syn was established by co-staining with the neuronal specific protein MAP-2, and the SNAP-25 marker was also probed to reveal presynaptic terminals, which showed similar partial colocalization with neuritic α-SynWT and α-SynG51D (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4C). However, and in accordance with our observations in HEK cells, whereas the Syn-208, Syn-211 and FL-140 antibodies detected mostly cytosolic localization in neuronal soma, the N19 (epitope N-terminal) and Syn-1 antibodies revealed the additional nuclear signal in primary neurons (Fig. 4F and Supplementary Material, Fig. S4). Importantly, neurons expressing α-SynG51D exhibited again enhanced nuclear localization compared with α-SynWT (Fig. 4G).

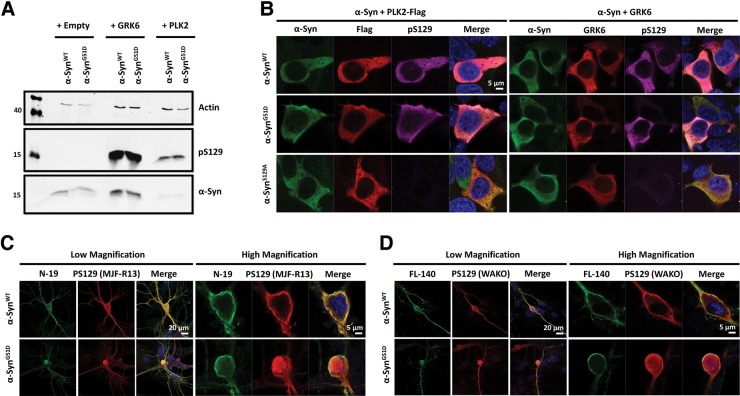

Nuclear α-SynG51D is hyper-phosphorylated at S129 in primary neurons

Previous studies have shown that α-Syn phosphorylated at S129 is enriched in the nucleus (45–48). These observations, combined with the fact that phosphorylation at S129 has been shown to regulate α-Syn degradation, aggregation and toxicity (49), led us to investigate whether the G51D mutation affects α-Syn phosphorylation at S129, and conversely, whether differences in S129 phosphorylation may explain the enhanced nuclear localization of α-SynG51D. Therefore, we first transiently co-expressed α-SynWT or α-SynG51D in HEK cells with PLK2 and GRK6; two kinases known to efficiently phosphorylate α-Syn at S129 (46,50), and assessed phosphorylation biochemically and by immunofluorescence analysis. As shown in Figure 5A, HEK cell lysates expressing α-SynWT or α-SynG51D together with GRK6 or PLK2 showed that both α-Syn forms are readily phosphorylated at S129. Moreover, co-expressing α-SynWT or α-SynG51D with PLK2 (but not GRK6) induced significant degradation of α-Syn, as recently described by our group for α-SynWT (51). Similar results were obtained from triple immuno-labeling experiments where α-SynWT and α-SynG51D were efficiently phosphorylated at S129 by PLK2 and GRK6 (Fig. 5B). The specificity of the phospho-specific antibody used (WAKO) was confirmed by the fact that it did not stain a non-phosphorylatable α-Syn mutant “α-SynS129A” when co-expressed with both kinases (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

The G51D mutation enhances nuclear α-Syn S129 phosphorylation in primary neurons. (A) Western blot analysis shows that both α-SynWT and α-SynG51D are readily phosphorylated by PLK2 or GRK6 at S129, as HEK cells co-overexpressing α-Syn and each of these kinases show prominent phosphorylation at S129. Moreover, co-expressing α-SynWT or α-SynG51D with PLK2 induced significant degradation of α-Syn as recently described by our group for α-SynWT (51). As controls, HEK cells were transfected with α-SynWT or α-SynG51D together with empty vector, and actin was used as a loading control. (B) Triple immuno-labeling of HEK cells co-expressing α-SynWT or α-SynG51D with PLK2 (left panel) or GRK6 (right panel) shows that both proteins are efficiently phosphorylated at S129 by these kinases. The N19 antibody (N-terminal epitope) was used to detect α-Syn, and the specificity of the used phospho-specific antibody (WAKO anti-pS129) was established as the non-phosphorylatable S129A mutant shows no pS129 signal when co-expressed with PLK2 or GRK6. Note that in the case of PLK2 overexpression, cells expressing similar levels of α-Syn were imaged in order to allow comparison of subcellular distribution. (C and D) Double immuno-labeling of neurons expressing α-SynWT or α-SynG51D using the N19 antibody for total α-Syn and MJF-R13 for pS129 (C), or FL-140 antibody for total α-Syn and WAKO for pS129 (D) shows that both α-SynWT and α-SynG51D are efficiently phosphorylated at S129 by endogenous kinases in the soma and terminals (left panels), with α-SynG51D exhibiting stronger nuclear pS129 signal compared to α-SynWT (C and D; right panels).

In order to investigate the effect of the G51D mutation on S129 phosphorylation in primary neurons, we performed double immuno-labeling experiments on neuronal cultures expressing α-SynWT or α-SynG51D using antibodies against total and pS129 α-Syn. As shown in Figure 5C and D, immuno-labeling using the MJF-R13 or WAKO pS129 specific antibodies showed that α-SynWT and α-SynG51D are both efficiently phosphorylated at S129 by endogenous kinases in soma and neurites. Strikingly, the α-SynG51D mutant exhibited much stronger nuclear pS129 signal compared with α-SynWT (Fig. 5C and D). This effect was observed using the two pS129 specific antibodies, and even when the anti-total α-Syn antibody “FL-140” did not detect the enhanced nuclear localization of the mutant (Fig. 5D), hence ruling out any non-specific signals arising from total α-Syn imaging in the nucleus.

α-SynG51D exacerbates mitochondrial fragmentation in primary neurons

We next assessed whether the G51D mutation confers any toxic effect to α-Syn in neurons, and determined the effect of the α-SynWT versus α-SynG51D expression on mitochondrial fragmentation; a robust phenotype indicative of cellular stress that has been established for α-SynWT (52,53). Notably, although both WT and mutant α-Syn provoked abnormalities in mitochondrial structure, as evidenced by detection of Mito-YFP positive fragmented and enlarged structures (Fig. 6A), the effect of the G51D mutant was more pronounced, as shown by the quantification of neurons expressing α-Syn and exhibiting this abnormal mitochondrial phenotype. To determine whether this affected neuronal viability, we transiently expressed α-SynWT or α-SynG51D in primary neurons, and monitored the number of dead cells over time using the Sytox green exclusion assay. In line with previous reports (54,55), expression of α-SynWT did not provoke prominent toxicity (Fig. 6B). Moreover, α-SynG51D transfection showed similar levels of Sytox green fluorescence compared to transfection with the empty vector control, hence suggesting that α-SynG51D expression does not lead to neuronal death per se.

Figure 6.

The G51D mutation exacerbates mitochondrial fragmentation in primary neurons. (A) Immunocytochemical analysis using the Syn-211 antibody shows that both α-SynWT and α-SynG51D expressing neurons exhibit fragmented mitochondria compared with neurons transfected with empty plasmid (upper panel). To delineate mitochondria, the mitochondrial marker Mito-YFP was co-expressed with α-Syn encoding vectors. Quantification of neurons co-expressing α-Syn and Mito-YFP showed that α-SynG51D expression exacerbates mitochondrial fragmentation, as more neurons manifesting Mito-YFP clumps (larger than in 1 µm in diameter) were identified upon α-SynG51D expression (lower panel). The asterisk represents significance at P < 0.05 (at least 25 neurons per condition were quantified and the experiment was performed three independent times). (B) The Sytox green dye exclusion assay was used to assess the amounts of dead neurons upon transfection with empty vector, α-SynWT or α-SynG51D for 24, 48 and 72 h. The upper panel shows representative images of neurons 24 h post transfection, stained with the Syn-211 anti-human α-Syn antibody, and the anti-MAP2 antibody to reveal transfected and total neurons, respectively. Quantification (n = 3) of Sytox green fluorescence intensity over time is shown in the lower panel. Neurons treated with 200 μm H2O2 for 24 h were used as positive controls showing toxicity (i.e. high Sytox green fluorescence).

The G51D mutation enhances α-Syn secretion by differentiated neuroblastoma cells

Given that α-Syn has been consistently reported in biological fluids such as CSF (56,57), blood plasma (58–60) and saliva (61,62), and increasing evidence from in vivo and cell culture models supports a role for extracellular α-Syn in seeding and spreading pathology in a prion-like manner (63–66), we probed the effect of the G51D mutation on α-Syn secretion by differentiated SHSY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Strikingly, analysis of the conditioned media (CM) derived from cells overexpressing WT or mutant α-Syn showed increased levels of secreted monomeric and high molecular weight (HMW) α-SynG51D compared to the WT protein (Fig. 7A and B), although similar levels of both proteins were detected in cellular lysates. To rule out the possibility of the G51D mutant being more toxic and hence leading to increased α-Syn levels in CM due to membrane permeabilization, we measured the levels of a cytosolic housekeeping protein “lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)” in CM. Using this assay, we did not observe any significant difference in LDH release between α-SynWT and α-SynG51D (Fig. 7C), suggesting that the G51D mutation promotes α-Syn secretion by SHSY5Y cells.

Figure 7.

The G51D mutation enhances α-Syn secretion by neuroblastoma cells. (A) Biochemical analysis of SHSY5Y cells expressing α-SynWT or α-SynG51D shows that although similar levels of both proteins are expressed in total cellular lysates, more monomeric and HMW α-SynG51D is detected in extracellular CM. Actin was used as a housekeeping gene denoting equal protein loading of cellular lysates. (B) Densitometric quantification (n = 3) of monomeric α-Syn released into CM (normalized against total α-Syn levels in Tris-soluble fractions) shows ∼50% increase in secreted levels of α-SynG51D compared to α-SynWT at P < 0.01. (C) Quantification (n = 3) of released LDH in CM shows no significant difference between α-SynWT and α-SynG51D.

Immunohistochemical analysis of post-mortem human brains reveals Thioflavin-S positive α-SynG51D that only partially colocalizes with nuclear membrane markers

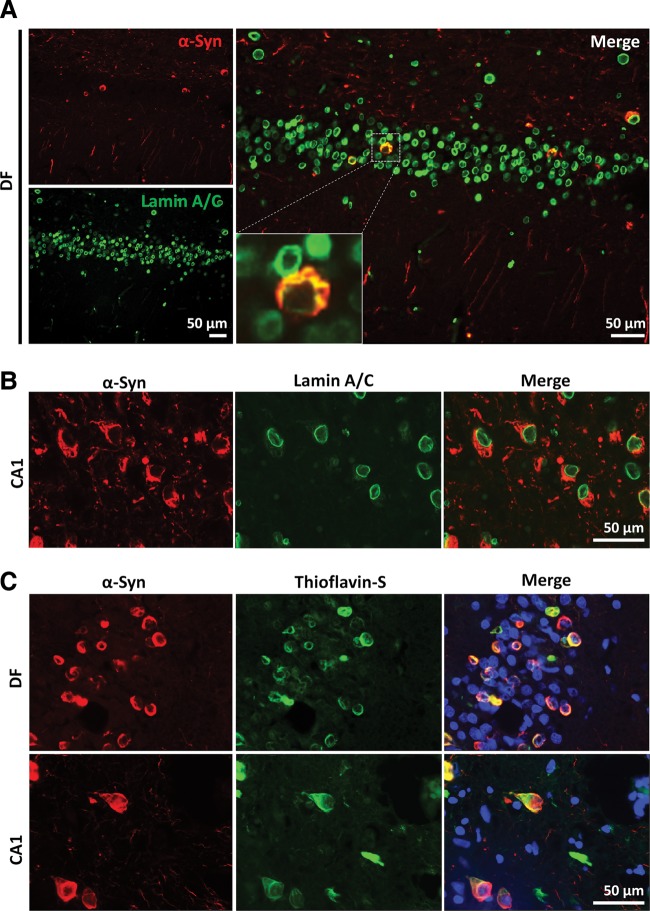

Finally, we set out to assess the effect of the G51D mutation on the distribution of α-Syn in human brains. Therefore, double immunofluorescence analysis of α-Syn with nuclear envelope markers (Lamin A/C) was performed on paraffin embedded sections of human post-mortem α-SynG51D cases (n = 3). Notably, only partial colocalization of α-Syn with Lamin A/C was apparent, particularly in regions which have an abundant accumulation of annular type inclusions, including the posterior frontal cortex and the dentate fascia (Fig. 8A). This colocalization was less apparent in regions having greater populations of NFT-like inclusions such as the CA1 of the hippocampus (Fig. 8B). Importantly, this experiment was repeated using different antibodies (Figure S3B), and again, no evidence of strong α-Syn expression within the nucleus was detected (data not shown).

Figure 8.

α-SynG51D from post-mortem human brains is Thioflavin-S positive and partially colocalizes with nuclear envelope proteins. (A) Representative double immunofluorescence images of α-Syn (red) and Lamin A/C (green) reveal annular type inclusions of the dentate fascia (DF) of post-mortem α-SynG51D cases which partially colocalize with Lamin A/C. (B) α-Syn inclusions having NFT-like morphology of the CA1 region show less colocalization with Lamin A/C. Scale bars represent 50 µm. (C) α-SynG51D colocalizes with Thioflavin-S indicating amyloid conformation. Representative double immunofluorescence images of α-Syn expression (red) and Thioflavin-S (green) staining in DF and CA1 regions of post-mortem α-SynG51D cases.

To investigate the conformational state of α-SynG51D, double immunofluorescence microscopy of α-Syn with Thioflavin-S was performed on paraffin embedded sections of frontal and temporal cortex of post-mortem brain tissues of α-SynG51D cases. Sections double stained with α-Syn and Thioflavin-S examined by confocal microscopy confirmed the presence of α-SynG51D in an amyloid conformation within inclusions (Fig. 8C).

DISCUSSION

The G51D mutation attenuates α-Syn aggregation in vitro

Given that α-Syn aggregation into amyloid fibrils has been established as a central event in the pathogenesis of PD, we first assessed the impact of the recently reported G51D mutation on α-Syn aggregation. Strikingly, the aggregation of α-SynG51D in vitro was significantly attenuated compared with α-SynWT as assessed by ThT binding and CD spectroscopy. However, analysis of remaining soluble content revealed less difference in aggregation propensity between the G51D mutant and α-SynWT. This finding was confirmed and explained by TEM imaging of the aggregates formed by both proteins. At early time points, α-SynG51D forms amorphous aggregates that are ThT negative but readily sediment upon centrifugation. As such, these results suggest that the G51D mutation favors the formation of “off-pathway” amorphous aggregates, which re-enter the amyloid pathway upon depletion of monomeric α-Syn. A similar, however, less prominent attenuation in fibrilization has been reported in the case of the A30P mutant (67–69), whereas all other reported mutations (A53T, E46K and the recently described H50Q) showed enhanced aggregation propensities. In fact, increased levels of amorphous aggregates were also demonstrated for the A30P mutant (67), suggesting that both G51D and A30P mutants may share similarities in aggregation behavior. Notably, one of the two studies initially reporting the identification of the G51D mutation showed no effect on α-Syn aggregation in vitro (18). Given that the aggregation studies carried out by Lesage et al. (18) were performed at a high protein concentration (100 μm), compared with the relatively low concentration used in this study (10 μm), we assessed whether this discrepancy was due to the difference in concentration. However, even when increasing the concentration to 100 µm, the G51D mutant exhibited significantly slower aggregation kinetics compared to α-SynWT (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2C).

The G51D mutation impairs α-Syn interaction with SDS micelles and lipid vesicles in vitro, attenuates membrane binding in yeast and enhances secretion in mammalian cells

Given that the glycine 51 residue is located in a region that is known to become helical upon interaction with vesicles (Supplementary Material, Fig. S5A) (7,8), we investigated the effect of the G51D mutation on α-Syn membrane binding in vitro. Both NMR and CD studies revealed that although the G51D mutation does not have a significant effect on the structure of the free protein in aqueous solution, the substitution of a glycine for a negatively charged aspartate has a significant effect on α-Syn membrane interactions. In the presence of the anionic detergent SDS, which has been commonly used as a membrane mimic for α-Syn structural studies, the N-terminal region of α-SynWT forms a broken-helix state composed of two antiparallel helices connected by a short linker (residues 37–45) (10,20–22). The G51D mutation, which occurs near the N-terminal end of helix-2, significantly decreases the helicity of residues 45–55, suggesting a destabilization effect on the interactions of helix-2 with the micelle surface, possibly resulting in N-terminal fraying. This destabilization is likely a result of the introduction of a negative charge in the apolar face of helix-2 (10,20) (Supplementary Material, Fig. S5B), which is likely to perturb the ability of this region of the amphipathic helix to interact with the hydrophobic interior of the detergent micelle.

When α-Syn binds to lipid vesicles, it adopts an extended-helix conformation in which the linker region between helix-1 and helix-2 of the micelle-bound state converts to a helical conformation (70), fusing the two separate helices into one long uninterrupted helix. Models of the extended-helix state (20,71) indicate that the G51D mutation would again introduce a charged residue into the apolar face of the helix (Supplementary Material, Fig. S5A). In contrast to what is observed for the micelle-bound state, however, our NMR data reveal that the effect of the G51D mutation is not limited to perturbing local binding, but instead leads to decreased binding of the entire region C-terminal to the mutation. This indicates that the helix-2 region is essentially detached from the vesicle surface, while the N-terminal helix remains attached. Consistent with this observation, CD analysis of α-Syn incubated with different POPG lipid ratios revealed that α-SynG51D shows significantly reduced lipid biding propensity compared to the WT protein.

We have previously suggested (72,73) that helix-1 and helix-2 can act as partially independent binding modules on vesicle surfaces, and a variety of experimental observations support the existence of vesicle-binding modes where helix-1 (or parts thereof) are bound while helix-2 is not (24,26–28). Such states have also been proposed to facilitate membrane-induced aggregation of α-Syn (26,49,72). It appears that by disrupting protein–membrane interactions in the N-terminal region of helix-2, the G51D mutation favors the formation of such conformations. Consistent with this hypothesis, we show that membrane-induced aggregation of α-SynG51D is favored at all protein to lipid ratios, while the aggregation of α-SynWT is inhibited in large lipid excess, due to the strong α-helical conformation of the protein. These results further confirm that partially folded states favor α-Syn aggregation and suggest that the lack of strong α-helical conformation of the G51D mutant could allow its aggregation in the presence of lipids and hence explain to some extent its role in disease.

In order to determine whether the G51D mutation similarly affects α-Syn binding to biological membranes, we first expressed WT and mutant α-Syn (C-terminally YFP-tagged) in yeast cells. Strikingly, and in line with our in vitro data, the G51D mutation impaired α-Syn's membrane binding ability, and was not toxic to the yeast cells, an effect that was very similar to that of the A30P mutant (31). From a functional perspective, it is interesting to compare the G51D mutation's effects on α-Syn membrane interactions with those of the A30P mutation, which until now was the only known disease-linked mutation that significantly influenced this aspect of α-Syn physiology. Given the similarities in aggregation and membrane binding behavior of α-SynA30P and α-SynG51D, one could hypothesize that both mutants contribute to Parkinson's pathology via common mechanisms. In fact, although located in different helical segments (A30P is located in helix-1 while G51D is located in helix-2), they both destabilize the formation of their cognate helices, leading to a partly helical state at the membrane. Notably, we were not able to detect differences in membrane binding of α-SynG51D compared with α-SynWT when overexpressed in HEK cells. This is likely due to our assay having weak discriminatory strength in these cells, especially that as we also could not detect reduced membrane binding of the A30P mutant, which has been extensively shown to exhibit reduced membrane binding in vitro and in cell free systems (38,40). In line with this, a previous report showed that overexpressed α-SynA30P in mammalian HeLa cells exhibits reduced binding to lipid droplets formed upon treatment with high concentration of fatty acids, albeit not showing major differences in overall distribution without such treatment (39). Therefore, it remains unclear whether the membrane binding potential of α-SynG51D is affected in mammalian cells upon mere overexpression alone.

Given that α-Syn has been shown to be secreted via vesicle-mediated exocytosis, and the increasing interest in the role of extracellular α-Syn in seeding and spreading of pathological α-Syn, we investigated whether the G51D mutation influences α-Syn cellular secretion. Strikingly, increased levels of secreted monomeric and HMW α-SynG51D were detected in CM of SHSY5Y cells. This effect was not due to non-specific release of α-Syn due to cell death, as LDH levels in CM were not affected by α-Syn overexpression, and HMW α-Syn was not detected in cytosolic extracts. Taken together, these results suggest that, although α-SynG51D localization at the membrane does not seem to differ from that of the WT protein, its folded state, which is affected by the glycine to aspartate mutation, could be leading to a partially folded conformation that potentially enhances its active secretion in SHSY5Y cells, and that membrane binding could be an important regulator of this process. On another note, until recently, it was believed that oligodendroglia do not express α-Syn and therefore the origin of the α-Syn contributing to GCIs in MSA was uncertain. Although it now seems that oligodendrocytes can express α-Syn mRNA (74), there may also be a contribution from extracellular α-Syn, as it has been demonstrated that cultured oligodendrocytes can take up neuron-derived α-Syn from the extracellular medium (75). Thus, an increase in secretion of α-SynG51D could explain the finding of GCI-like inclusions in G51D mutation cases.

α-SynG51D exhibits enhanced nuclear localization in HEK cells, in primary neurons but not in post-mortem human brains of α-SynG51D cases

α-Syn was first discovered as a neuronal protein having presynaptic as well as nuclear localization (76). Since then, although the physiological role of α-Syn at the synapse has been extensively investigated and a regulatory role for α-Syn in presynaptic vesicle cycling and neurotransmitter release has been proposed (77–81), few studies have focused on the function of α-Syn within the nucleus. The nuclear distribution of α-Syn remains somewhat controversial, as conflicting results were obtained regarding the existence of endogenous α-Syn within neuronal nuclei (82–85). Based on published reports (48), as well as our data from this study, this discrepancy could be partially due to the use of different antibodies to detect α-Syn in various studies. In fact, our results show that some antibodies (such as Syn-1, EP1646Y and SA-3400) are more sensitive to detecting nuclear α-Syn than others (i.e. FL-140, Syn-208 and Syn-211), depending on the epitope they recognize, especially as it has been suggested that the α-Syn species in the nucleus could be truncated (86,87), and hence not detectable by some of the commonly used antibodies.

In this study, we observed prominent nuclear enrichment of the G51D mutant compared with α-SynWT in mammalian HEK cells using three independent approaches; biochemical subcellular fractionation, immunocytochemistry using antibodies detecting nuclear α-Syn as well as live imaging. Importantly, although overexpressed α-SynG51D exhibited enhanced nuclear localization in primary cultured neurons, immunohistochemical analysis of post-mortem human brain tissues of α-SynG51D cases did not reveal comparable nuclear signal for α-Syn. This lack of detection of nuclear α-Syn may be due to several technical issues. First, nuclear α-Syn may exist at a level which is below the sensitivity of the immunofluorescence technique, compared with the transient and acute overexpression of α-Syn that was performed in our cell and neuronal culture models. Secondly, the post-mortem delay period may affect the steady-state distribution of α-Syn, hence decreasing its effective nuclear concentration. Thirdly, nuclear α-Syn in paraffin sections may be physically inaccessible to the α-Syn antibodies that we have investigated, as this may be influenced by fixation time or require greater disruption of cell membranes. Finally, the conformation of nuclear α-Syn in human brains may be altered so that none of the antibodies we tested were capable of recognizing the protein in this subcellular compartment. Therefore, the subcellular localization of the α-SynG51D should be further investigated and verified in post-mortem human brain tissues of α-SynG51D cases, by optimizing protocols that allow robust detection of nuclear α-Syn by immunohistochemistry and biochemical assays.

It has been previously shown that the PD-linked mutations A30P and A53T exhibit increased nuclear targeting as well as enhanced speed of shuttling between the nucleus/cytoplasm in cell culture (44,88). Moreover, a recent study demonstrated that, in addition to the C-terminal domain that has been long associated with nuclear accumulation (42), amino acid residues 1–60, which span the region harboring all four PD-linked mutations, is indispensable for α-Syn nuclear import (43). Notably, we did not observe similar nuclear enrichment of the A30P mutant by biochemical fractionation of HEK cells. This suggests that the increased nuclear localization of α-SynG51D is not solely due to deficits in membrane binding, and that other molecular properties of this mutant may be promoting its aberrant distribution in our over expression models.

Given that several proteins associated with neurodegeneration have been found to exert their pathogenic effects when localized in the nucleus (89–92), it could be that the nuclear localization of PD-linked mutant α-SynG51D is at least a partial mediator of neurotoxic effects. In line with this, the handful of studies that have convincingly demonstrated nuclear localization of α-Syn in transfected mammalian cells, cultured primary neurons and in vivo have mainly proposed a neurotoxic function for α-Syn in neuronal nuclei that is not necessarily dependent on α-Syn aggregation. For instance, an elegant study by Kontopoulos et al. (88) showed that α-Syn binds directly to histones and reduces histone H3 acetylation, promoting toxicity both in cell culture and transgenic Drosophila. Similarly, an independent study by Goers et al. (93) showed using mice midbrain sections, that paraquat up-regulates α-Syn expression, nuclear localization and colocalization with acetylated H3 histones. Importantly, although the same report demonstrated that α-Syn interacts with histones in vitro, and that histones dramatically accelerate α-Syn fibrillization, nuclear α-Syn fibrils were not detected in paraquat treated brains, suggesting that the pathogenic effects of nuclear α-Syn localization could be independent of α-Syn aggregation. Further studies supported this notion, as they consistently reported increased nuclear accumulation of α-Syn in response to oxidative stress in dopaminergic neurons (86), which in turn enhances the susceptibility of dopaminergic cells (87), probably by accelerating the cell cycle (43), or the protein's ability to modulate the transcription of PGC-1α; a master mitochondrial transcriptional activator (94). Therefore, future studies should aim at elucidating the cellular factors promoting enhanced α-SynG51D nuclear localization, as well as assessing the result of this enhanced accumulation on PD pathology in different cellular and in vivo models.

Nuclear α-SynG51D is hyper-phosphorylated at S129 and exacerbates mitochondrial fragmentation in primary neurons

α-Syn phosphorylation at S129 has emerged as a pathological hallmark of PD and other synucleinopathies (49). Therefore, we sought to investigate whether the G51D mutation influences α-Syn phosphorylation at S129. Strikingly, whereas no interplay between S129 phosphorylation and the G51D mutation were observed using in vitro kinase assays or in HEK cells upon co-expression with two natural α-Syn kinases (PLK2 and GRK6), experiments in primary neurons showed that the α-SynG51D mutant exhibits much stronger nuclear phosphorylation by endogenous kinases compared to its WT counterpart. This discrepancy could be due to masking effects in HEK cells upon co-expression with kinases that efficiently phosphorylate α-Syn, or due to intrinsic neuronal properties. Importantly, our results are in line with previous reports, suggesting that nuclear α-Syn could be preferentially phosphorylated at S129 compared to cytoplasmic α-Syn (47), and also with reports suggesting enhanced phosphorylation of α-Syn PD mutants by endogenous kinases in human brains as well as in transgenic mice. In fact, detergent-insoluble α-Syn from PD brains bearing the A53T mutation was shown to be hyper-phosphorylated at S129 (95). Similarly, α-Syn inclusions from transgenic mice brains expressing either the E46K or A53T α-Syn mutants were also shown to have strong reactivity with pS129 antibodies (96), although the A53T mutant was previously reported to have similar phosphorylation levels to α-SynWT in SH-SY5Y cells (97), and slower in vitro phosphorylation kinetics by casein kinase 2 (CK2) (98). Moreover, the fact that transgenic mice expressing α-SynA53T showed strong nuclear accumulation of total and S129 phosphorylated α-Syn, together with the fact that we observe a similar effect with the novel G51D mutant in primary neurons further suggests a potential role for nuclear α-Syn in neuropathology (45,99). Finally, we investigated whether the α-SynG51D has any toxic effects in neurons. Although α-SynG51D expression was not toxic per se when total numbers of neurons were assessed, it provoked more pronounced mitochondrial fragmentation than α-SynWT, suggesting that this mutant may be conferring toxic properties to α-Syn in primary neuronal cells.

Summary and perspectives

In this study, we investigated the effect of the G51D mutation on the biophysical and cellular properties of α-Syn using a wide range of commonly used in vitro and cellular models. In vitro, α-SynG51D exhibited attenuated aggregation and impaired membrane binding. Both effects were recapitulated in yeast cells but not in mammalian cell lines or primary neurons. In contrast, the G51D mutant showed enhanced secretion, nuclear localization and phosphorylation in mammalian cells and primary neurons, where it exacerbated α-Syn-induced mitochondrial fragmentation. Nevertheless, immunohistochemical analysis of post-mortem human brain tissues of α-SynG51D cases revealed only partial colocalization with nuclear membrane markers. These findings suggest that effects of PD-linked mutations could be context dependent, and that properties of α-Syn variants should be investigated in different model systems. Future studies should focus on investigating the effects of this novel mutation further in vivo, by generating transgenic animal models expressing this mutant, and comparing side by side the toxicity, subcellular localization and phosphorylation of both proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and cloning

The pAAV-PGK human α-SynWT and the pT7-7 human α-SynWT plasmids were kindly provided by the laboratories of Prof. Patrick Aebisher, EPFL, Switzerland, and Prof. Peter Lansbury, Harvard Medical School, USA, respectively. For the generation of the pmEOS2–α-Syn fusion construct, human α-Syn cDNA was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and cloned into the pmEOS2-C1 plasmid (minus the start codon) to generate the mEOS2–α-Syn fusion. The G51D mutation was then introduced into the pAAV-PGK α-Syn, pT7-7 α-Syn and mEOS2-α-Syn plasmids using the QuikChange® site-directed mutagenesis system (Stratagene). For yeast experiments, an α-Syn Gateway® entry clone was obtained from Invitrogen, containing full-length human α-Syn in the vector pDONR221. To generate untagged α-Syn constructs, this entry clone was used in a Gateway LR reaction with pAG426GAL-ccdB to produce pAG426GALα-Syn. To generate C-terminally YFP-tagged TDP-43 constructs, PCR was performed to amplify α-Syn without a stop codon and incorporate SpeI and HindIII restriction sites along with a Kozak consensus sequence. The resulting PCR product was cloned into SpeI/HindIII digested pRS426GAL-YFP to generate the 2µ α-Syn-YFP fusion construct. Each PD-linked mutant construct was generated by using the QuickChange® site-directed mutagenesis system (Stratagene) with pRS426GAL–α-Syn-YFP as template. The pCDNA-CMV PLK2 and pCDNA-CMV GRK6 were kindly provided by the laboratories of Prof. Ingrid Hoffman, German Cancer Research Center, Germany, and Prof. Dario Diviani, UNIL, Switzerland, respectively. The plasmids encoding the membrane, endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial fluorescent markers were obtained from BD Biosciences, Clontech. All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Microsynth) and agarose gel electrophoresis.

Protein expression and purification

BL21(DE3) cells transformed with pT7-7 plasmid encoding for α-SynWT or α-SynG51D were grown in the LB medium at 37°C, and induced with 1 mm 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (AppliChem) for 4 h. Induced bacterial cultures were pelleted and lysed by sonication. After centrifugation at 48 000g for 20 min, the supernatant was boiled for 5 min and centrifuged again for 20 min. The supernatant was purified by anion-exchange (HiPrep 16/10 Q FF, GE Healthcare Life Sciences), followed by gel filtration (HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200, GE Healthcare Life Sciences), reverse phase C4 HPLC (Proto 300 C4, 20 mm I.D. × 250 mm, 10 µm average bead diameter, Higgins Analytical) and lyophilized. Isotopically labeled (15N and 15N,13C) α-SynG51D was generated as previously reported (7). Specifically, E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells expressing the α-SynG51D plasmid were first grown in rich media, then transferred to minimal media containing either 15N-labeled ammonium chloride or 15N-labeled ammonium chloride and 13C-labeled glucose for production of 15N-labeled or 15N-, 13C-labeled protein, respectively, before induction with IPTG (100). After 3.5 h of induction at 37°C, bacteria were lysed by sonication and the lysate was either directly used for NMR experiments or subjected to further purification, consisting of ammonium sulfate precipitation, anion-exchange chromatography, reversed-phase HPLC and lyophilization.

NMR experiments

NMR experiments were carried out on Varian Inova or Bruker Avance 600 or 800 MHz spectrometers equipped with cryogenic probes. All data were collected at 10°C, except for data from samples containing SDS, which were collected at 40°C. Purified protein concentrations were ∼150 µm for lipid binding experiments and 200 µm for SDS-binding experiments; protein concentration in experiments employing cell lysates was estimated at 200 µm. Backbone amide assignments were transferred from previously published WT assignments (7,20) for the free and SDS micelle-bound states of the protein using HNCA experiments. The free state HNCA was collected using fresh cell lysates with spectral widths of 12, 26 and 26 ppm and 1024, 48 and 84 complex points in the 1H, 15N and 13C dimensions, respectively. The SDS-bound HNCA was collected on lyophilized purified protein dissolved in NMR buffer (100 mm NaCl, 20 mm NaHPO4, pH 6.8) and mixed with SDS stock to a final concentration of 40 mm SDS, 200 µm protein, with spectral widths of 14, 28 and 26 ppm and 1024, 32 and 80 complex points in the 1H, 15N and 13C dimensions, respectively. NMR data were processed with NMR-Pipe (101) and analyzed with NMR ViewJ (102). The difference in the chemical shift of each amide cross-peak between the α-SynG51Dand α-SynWT spectra was calculated as Δδamide = √(½(ΔδHN2 + (ΔδN/5)2)). Secondary shifts were calculated as ΔδCa = δCa,meas – δCa,RC, using temperature- and neighbor-corrected random coil shifts published by Kjaergaard and Poulsen (103). Lipid-binding was assessed by comparing the bound population of α-SynG51D and α-SynWT at a single concentration of lipid vesicles, as reported by cross-peak intensities in matched 1H,15N-HSQC spectra of lipid-free and lipid-containing (15% DOPS 25% DOPE 60% DOPC SUVs) samples (23). SUVs were prepared as previously reported, with slight modification, by mixing chloroform-dissolved lipids, drying under nitrogen, resuspending in NMR buffer, sonicating and clarifying by ultracentrifugation (20). Purified lyophilized α-SynG51D was dissolved in NMR buffer and mixed with SUV stock solutions to a final concentration of 3 mm lipid and 150 µm protein. PRE samples were prepared by dissolving lyophilized protein containing the E20C mutation (∼200 µm final concentration) in NMR buffer with a 10-fold molar excess of the spin-label reagent S-(2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-2,5-dihydro-1H-pyrrol-3-yl)methylmethanesulfonothioate (MTSL), incubating for 1 h and removing excess spin-label using Sephadex G-25 beads. The conjugated protein solution was then split into two samples and DTT (2 mm) added to one, in order to reduce the spin-label and generate a diamagnetic control sample. Matched 1H,15N-HSQC spectra were then collected on the paramagnetic and diamagnetic samples, and the cross-peak intensity ratio taken to estimate the PRE effect in a sequence-specific manner.

In vitro fibrillization and sedimentation assays

Lyophilized proteins were dissolved in 50 mm Tris and 150 mm NaCl, pH 7.5 and filtered through a 100 kDa MW-cut-off filter. Fibril formation was induced by incubating the protein (10 µm) at 37°C and pH 7.5 (50 mm Tris and 150 mm NaCl) under constant agitation at 1000 rpm on an orbital shaker, for up to 120 h. Amyloid formation was monitored by Thioflavin T (ThT) binding, soluble protein content, circular dichroism (CD) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). ThT fluorescence reading (excitation wavelength of 450 nm, emission wavelength of 485 nm) was performed in triplicates with a ThT concentration of 10 μm and a protein concentration of 1 μm in 50 mm glycine pH 8.5, using a Bucher Analyst AD plate reader. To determine the remaining soluble protein content, aliquots of samples at each time point were centrifuged at 20 000g for 10 min at 4°C to pellet insoluble aggregates, and the supernatant was run on 15% SDS–PAGE, which was stained with a Coomassie R-450 solution. The relative amounts of soluble protein with respect to the initial conditions were determined by densitometry analysis (ImageJ).

Circular dichroism

CD was performed on a Jasco J-815 CD spectrometer at 20°C. CD spectra were acquired in the range of 195–250 nm using a 1.0 mm optical path length quartz cuvette. Data were collected using the following parameters: data pitch, 0.2 nm; bandwidth, 1 nm; scanning speed, 50 nm/min; digital integration time, 2 s. For each sample, five spectra were averaged and smoothed using binomial approximation.

Transmission electron microscopy

3.5 μl of sample was applied onto glow-discharged Formvar/carbon-coated 200-mesh copper grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 60 s. The grid was then blotted with filter paper, washed twice with ultrapure water, once with staining solution (Uranyl formate 0.7% w/V) and then stained for 30 s, blotted off and dried by vacuum suction. Imaging was carried out on a Tecnai Spirit BioTWIN electron microscope operated at 80 kV and equipped with a LaB6 gun and a 4K × 4K FEI Eagle CCD camera (FEI).

Lipid vesicle preparation

Phospholipids in chloroform (1-hexadecanoyl-2-(9Z-octadecenoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol), (POPG) from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. were dried using an argon stream to form a thin film on the wall of a glass vial. Potential remaining of chloroform was removed by placing the vial under vacuum overnight. The phospholipids were then resolubilized to the desired stock concentration by water bath sonication. The solution was then extruded through the Avestin LiposoFastTM (Avestin Inc.), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Multi angle light scattering

Thirty micromolar 100 KDa cut-off filtered samples were applied onto a Superdex 200 10/300 GL (GE Healthcare Life Sciences), on an Agilent technologies series 1200 instruments (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, UA) coupled to a refractive index detection (OptilabrEX, Wyatt Technology Corporation) and eight-angles light scattering detectors (DAWN 8+, Wyatt Technology Corporation). Molecular weight determination was performed using the Astra 5.3 analysis software (Wyatt Technology Corporation).

Yeast strains, media, transformation, spotting and imaging

Yeast cells were grown in rich media (YPD) or in synthetic media lacking uracil and containing 2% glucose (SD/-Ura), raffinose (SRaf/-Ura) or galactose (SGal/-Ura). 2 µ plasmid constructs (e.g. pRS416GALα-Syn-YFP) were transformed into BY4741 (MATa his3 leu2 met15 ura3) according to standard protocols. We used the PEG/lithium acetate method to transform yeast with plasmid DNA. For spotting assays, yeast cells were grown overnight at 30°C in liquid media containing SRaf/-Ura until they reached log or mid-log phase. Cultures were then normalized for OD600, serially diluted and spotted with a Frogger (V&P Scientific) onto synthetic solid media containing glucose (SD/-Ura) or galactose (SGal/-Ura) lacking uracil and were grown at 30°C for 2–3 days. For fluorescence microscopy experiments, single colony isolates of the yeast strains were grown to mid-log phase in SRaf/-Ura media at 30°C. Cultures were spun down and resuspended in the same volume of SGal/-Ura to induce expression of the α-Syn-YFP constructs for 6 h before being processed for microscopy.

HEK293T cell culture and transfection

HEK293T cells were grown at 37°C, with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, GIBCO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, GIBCO) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were then plated on cover slips (12 mm, Milian) which had been precoated with poly-l-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich) for immunocytochemistry, in six-well plates for biochemistry, or in 35 mm fluorodishes (World Precision) for live imaging experiments, and then transfected with appropriate plasmids using the standard calcium phosphate (CaPO4) transfection method. Cells were maintained at 37°C and analyzed 24 h post transfection.

HEK293T protein extraction and western blotting

Cells were harvested and lysed with 80 µl lysis buffer/well (20 mm Trizma base, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.25% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% Triton-X, pH 7.4) supplemented with 1 mm PMSF (Sigma) and 1:100 protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). The lysates were vortexed and then kept on ice for 30 min before being centrifuged at 20 817g for 15 min at 4°C. The total protein amount in the supernatant (Triton-soluble) was determined using the BCATM protein assay kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Equal protein amounts were then separated on 16% SDS 1.5 mm gels and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane using a semi-dry transfer cell from Bio-Rad. The membrane was then blocked for 1 h at RT with Odyssey blocking buffer (Li-COR Biosciences GmbH) diluted 1:3 in PBS, and probed with primary antibodies (Supplementary Material, Table S1) at 4°C overnight. After three washes in PBST [PBS 0.01% (v/v) Tween-20 (Fluka)], the membrane was incubated with Alexa Fluor (680 or 800 nm) conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA; Li-COR Biosciences GmbH) at RT for 1 h, washed three times with PBST and scanned using a Li-COR scanner at a wavelength of 700 or 800 nm.

Subcellular fractionation of HEK293T cells

The fractionation of HEK293T cells was carried out employing the subcellular proteome extraction kit (Calbiochem Cat. 539790) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The fractions were analyzed by western blotting, and their purity was established using control antibodies against markers of subcellular compartments provided by the kit (Hsp90 for cytosol and Parp-1 for the nuclear fraction) at 1:1000 dilution in blocking buffer.

Maintenance of differentiated SH-SY5Y cell lines and transfection

SH-SY5Y cells were cultured and differentiated as described previously (65). Briefly, cells were cultured in 10 mm dishes and differentiated with 10 ml of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% Pen/Strep and 50 µm Retinoic Acid (RA) in a humidified incubator at 37°C. To maintain the cells in differentiated conditions, the growth media was renewed every 2 days until the day of experiment. Cells were then electroporated with 10 µg of DNA and kept at 37°C for 48 h to allow optimal expression of the transgene.

Preparation of CM from SH-SY5Y cells

At 48 h post transfection, cells were washed two times with pre-warmed DMEM and incubated for 18 h with fresh DMEM without FBS. The culture supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 1000g for 10 min at 4°C to pellet cellular debris. The supernatant was centrifuged again at 10 000g for 15 min at 4°C, and the conditioned medium was collected and analyzed by western blot. To obtain cellular lysates, cells were harvested and lysed in lysis buffer [1% Triton X-100 in cold PBS supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)]. After a 10 min incubation on ice, the cell lysate was centrifuged at 16 000g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant (Triton-soluble fraction) was collected in a new clean tube. The concentrations of the samples were determined by BCATM (Pierce) protein assay kit, and equal amounts of proteins per sample were resolved in 12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and proceeded for western blot.

Primary neuron culture preparation and transfection

Primary hippocampal neuronal cultures were prepared from P0 WT mice (Harlan Laboratories, Netherlands) as previously described (104). Briefly, hippocampi were dissociated with papain and triturated using a glass pipette. After centrifugation at 400g for 2 min, cells were plated in MEM/10% FCS onto poly-l-lysine (BD Biosciences) coated cover slips (12 mm, VWR) at 1.5 × 105 cells/ml. Medium was changed after 4 h to Neurobasal/B27 medium, and neurons were treated with ARAC (Sigma) after 6 days to stop glial division. After 7 days in vitro (DIV), neurons were transiently transfected with 0.5 µg of plasmid using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and analyzed 48 h later.

Immunocytochemistry

HEK cells or primary neurons were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and then incubated in blocking buffer [3% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.02% Saponin in PBS] for 1 h at RT. Then, cover slips were incubated overnight at 4°C in blocking buffer comprising primary antibodies (Supplementary Material, Table S1). Subsequently, cover slips were washed three times with PBS and incubated in blocking buffer comprising appropriate Alexa Fluor conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) as well as the nuclear stain 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1:5000) for 1 h at RT. After three washes with PBS, cover slips were washed once with double distilled water and then mounted on glass slides with DABCO mounting medium (Sigma-Aldrich). Stained samples were then imaged using the LSM700 point scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Live imaging photoconversion experiments

Photoconversion was performed using the LSM 700 inverted point scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with an incubated stage maintained at 37°C, using a Plan-Apochromat 40×/1.3 Oil DIC M27 objective. Transfected cells were first identified using a 488 nm laser (2% transmission) and a 515–565 nm band pass filter to detect unconverted mEOS2. Then, a circular region of interest (ROI, r = 1 µm) was photoconverted using a diode laser at 405 nm (20% transmission) in the cytoplasm. Photoconverted mEOS2 was detected upon excitation with a 555 nm diode laser, and then around 70 images (frame size 512 × 512, 0.06 × 0.06 µm, 8 bit, pixel time: 0.64 µs) were acquired with an interval of around 4 s with the pinhole set to 1 Airy unit for each cell. Photoconversion was performed after the second image and was repeated after every image acquisition. Around 25 neurons per condition were analyzed. Time-lapse series of images showing mEOS2 fluorescent intensities were analyzed to measure photoconverted mEOS2 intensities over time in the nucleus using the LSM Zen 2012 (blue edition) software.

LDH and Sytox green cytotoxicity assays

To assess the membrane integrity in SH-SY5Y cells, LDH cytotoxicity assay was performed on cell culture media using the LDH cytotoxicity kit (Takara BIO INC, cat: MK401) as per manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 20 µl of crude CM was diluted 5-fold in PBS and incubated for 30 min at RT with equal amounts of catalyst solution (Diaphorase/NAD+) in the dark. The enzymatic reaction was quenched with 2N HCl and absorbance was immediately quantified at 490 nm. To assess the membrane integrity in neurons, the Sytox green dye exclusion assay was performed using Sytox green reagent (Molecular probes, Invitrogen) as per manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, Sytox green dye was diluted (1:5000) in media of neurons plated and transfected in 96-well clear bottom black plates (Corning, Cat: 3603), and then incubated for 30 min at 37°C in the dark. Neurons were subsequently washed twice with PBS, and then fluorescence intensity per well was measured after adding 100 µl of PBS per well using the Infinite M200-Pro plate reader (Excitation: 487 nm; Emission: 519 nm). Neurons were then fixed and immunocytochemistry was performed as described above.

Analysis of post-mortem human brains

Brain tissue was donated to the Queen Square Brain Bank for Neurological Disorders, UCL Institute of Neurology using ethically approved protocols and stored for research under a license issued by the human Tissue Authority (No. 12198). Following division in the saggital plane, one half of each brain was sliced in the coronal plane and immediately flash frozen and stored at −80°C. Following fixation in 10% buffered formalin, the remaining half brain was sliced in the coronal plane, examined and blocks were selected for paraffin wax embedding and histology. Three G51D SNCA mutation cases were used in this investigation, and the presence of the point mutation had been confirmed by Sanger sequencing for exon 3 of SNCA. Paraffin embedded sections (8 μm thick) were stained using primary antibodies: α-Syn (Abcam, UK), Lamin A/C and Lamin B (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, CA, USA). Double immunofluorescence was detected using isotype specific anti-rabbit IgG or anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies conjugated with either Alexa 488 or 594 fluorescent dyes (1:400) (Life technologies) followed by quenching of auto-fluorescence with 0.1% Sudan Black/70% Ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) solution for 10 min and mounting with glass cover slips using VECTA-shield mounting media with DAPI nuclear stain (Vector laboratories). Images were taken using fluorescence microscopy (Leica DM5500 B). In order to determine the conformational state of α-SynG51D, paraffin embedded (8 µm thick) sections from frontal lobe and hippocampal regions were prepared for double staining with α-Syn and Thioflavin S. Sections were pre-treated using 70% formic acid and α-Syn was incubated overnight followed by biotinylated anti-rabbit antibody, and finally ABC reagent. Sections were finally counterstained in aqueous Thioflavin S.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

FUNDING

This work was supported by researchers at the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre; by the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology and Swiss National Science Foundation (H.L.); National Institutes of Health (R37AG019391 to D.E.); NYSTAR and ORIP/NIH facility improvement grant (CO6RR015495 to D.E.); a gift from Herbert and Ann Siegel (D.E.); the Reta Lila Weston Institute for Neurological Studies (J.H.) and the Multiple System Atrophy Trust (J.H., A.K.).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Nathalie Jordan, John Perrin, Celine Vocat and Trudy Ramlall for their excellent technical expertise, and Prof. Virginia Lee for kindly providing the Syn-208 antibody.

Conflict of interest Statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goedert M., Spillantini M.G., Del Tredici K., Braak H. 100 years of Lewy pathology. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2013;9:13–24. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polymeropoulos M.H., Lavedan C., Leroy E., Ide S.E., Dehejia A., Dutra A., Pike B., Root H., Rubenstein J., Boyer R., et al. Mutation in the alpha-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson's disease. Science. 1997;276:2045–2047. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baba M., Nakajo S., Tu P.H., Tomita T., Nakaya K., Lee V.M., Trojanowski J.Q., Iwatsubo T. Aggregation of alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies of sporadic Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Am. J. Pathol. 1998;152:879–884. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lashuel H.A., Overk C.R., Oueslati A., Masliah E. The many faces of alpha-synuclein: from structure and toxicity to therapeutic target. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013;14:38–48. doi: 10.1038/nrn3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bendor J.T., Logan T.P., Edwards R.H. The function of alpha-synuclein. Neuron. 2013;79:1044–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinreb P.H., Zhen W., Poon A.W., Conway K.A., Lansbury P.T., Jr. NACP, a protein implicated in Alzheimer's disease and learning, is natively unfolded. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13709–13715. doi: 10.1021/bi961799n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eliezer D., Kutluay E., Bussell R., Jr., Browne G. Conformational properties of alpha-synuclein in its free and lipid-associated states. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;307:1061–1073. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson W.S., Jonas A., Clayton D.F., George J.M. Stabilization of alpha-synuclein secondary structure upon binding to synthetic membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:9443–9449. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahn K.J., Paik S.R., Chung K.C., Kim J. Amino acid sequence motifs and mechanistic features of the membrane translocation of alpha-synuclein. J. Neurochem. 2006;97:265–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ulmer T.S., Bax A., Cole N.B., Nussbaum R.L. Structure and dynamics of micelle-bound human alpha-synuclein. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:9595–9603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411805200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]