Abstract

Trophoblast invasion into uterine tissues represents a hallmark of first trimester placental development. As expression of serum amyloid A4 (SAA4) occurs in tumorigenic and invasive tissues we here investigated whether SAA4 is present in trophoblast-like human AC1-M59/Jeg-3 cells and trophoblast preparations of human first trimester and term placenta. SAA4 mRNA was expressed in non-stimulated and cytokine-treated AC1-M59/Jeg-3 cells. In purified trophoblast cells SAA4 mRNA expression was upregulated at weeks 10 and 12 of pregnancy. Western-blot and immunohistochemical staining of first trimester placental tissue revealed pronounced SAA4 expression in invasive trophoblast cells indicating a potential role of SAA4 during invasion.

Keywords: SAA4, Placenta, Invasion, Cytokine, Outgrowing extravillous trophoblast

Highlights

-

•

SAA4 mRNA is expressed in Jeg-3 and AC1-M59 cells.

-

•

SAA4 mRNA is expressed in first trimester/term trophoblast cells.

-

•

SAA4 mRNA is upregulated at pregnancy week 10 and 12.

-

•

SAA4 protein is present in interstitial, intramural and intraluminal trophoblast cells.

1. Introduction

The serum amyloid A (SAA) family comprises lipoprotein-associated proteins, encoded by different genes with a high allelic variation [1,2]. In humans, the non-glycosylated SAA1/2 proteins, highly induced during the acute-phase response [3], are considered as important clinical markers of inflammation [4]. While human SAA3 is a pseudogene, SAA4 codes for glycosylated SAA4 protein that represents the predominant SAA isoform under physiological conditions. Although the liver is the major source for SAA4 assumed to be constitutively expressed [5–7], some studies reported abundant expression specifically in tumorigenic tissues [8–11].

Acute-phase SAA1/2 is expressed in human placenta, trophoblast cells and choriocarcinoma cell lines [12–14]. Therefore, the present study aimed at identifying SAA4 in (i) human Jeg-3 choriocarcinoma and AC1-M59 cells (hybrid of term trophoblast cells and AC-1 cells derived from Jeg-3), (ii) trophoblast cells of human first trimester and term placenta and (iii) outgrowing human first trimester extravillous trophoblast (EVT) cells.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture experiments

Placental tissues were obtained from born placentas of healthy pregnancies and from clinically normal human pregnancies, which were interrupted for psychosocial reasons (approved by the Ethical Committee at the Medical University of Graz [23-203 ex 10/11] and the Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena [1503-03/05]). Mononucleated human first trimester and term trophoblast cells were isolated as described [15,16]. Outgrowing EVT cells were isolated from placental villi after terminations of pregnancy (7–10 weeks, n = 5) and were incubated in Petri dishes for two days at 5% CO2 in DMEM/Ham's F12 with 10% (v/v) human serum. Then the villi were transferred into collagen-coated 24-well plates (two explants/well) and incubated at 2.5% O2, 5% CO2. After three days of culture the villi were removed from the plates and the already outgrown cells were cultured for another day at 5% CO2. Human hepatocellular carcinoma (HUH-7) cells, human Jeg-3 and human AC1-M59 cells were cultured as described [12,17,18]. AC1-M59 and Jeg-3 cells were seeded into cell culture dishes and upon reaching 80% confluence, incubated for 24 h in medium containing 10 ng/ml IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, or TNFα (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

2.2. RNA isolation, RT-PCR and real-time RT-PCR (qPCR) analysis

RNA was isolated from (i) AC1-M59, Jeg-3, EVT, HUH-7 (using RNeasy Mini Kit from QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) and (ii) first trimester (week 6–12) and term trophoblast cells (week 35 and 40) using Trizol-reagent (Sigma–Aldrich, Saint-Louis, MO, USA), followed by DNase treatment, reverse transcription and PCR for SAA4 and GAPDH (used as a housekeeping gene, see Supplementary Table I) as described [19]. The qPCR protocol was performed using LightCycler 480 system (Roche Diagnostics, Vienna, Austria) [20]. Gene specific primers used for SAA4 and HPRT (used as a housekeeping gene) are listed in the Supplementary Table II. Relative gene expression levels compared to HPRT were calculated using ΔΔCT method.

2.3. Western-blot analysis

Total cellular proteins were isolated [16] and 50 μg of protein (as assessed by the BCA method) was subjected to Western-blot analysis as described [19]. Rabbit polyclonal anti-human SAA4 antiserum (raised against amino acids 94-112 of human SAA4; dilution 1:300) not cross-reacting with human SAA1/2 was used as primary antibody [21].

2.4. Immunohistochemistry of first trimester placenta

Placental specimens from elective terminations of pregnancy (7–10 weeks, n = 5) were fixed in formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Sections of 5 μm were dewaxed and stained for SAA4 (polyclonal anti-SAA4 peptide antibody [21], dilution 1:500) or HLA-G (monoclonal antibody 4H84, 1:2000, BD Biosciences, NJ, USA) using labelled polymer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) and 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (Dako, Inc., Carpinteria, CA, USA) to detect antibody binding [22]. Control experiments were performed using rabbit or mouse non-immune serum or IgG.

3. Results and discussion

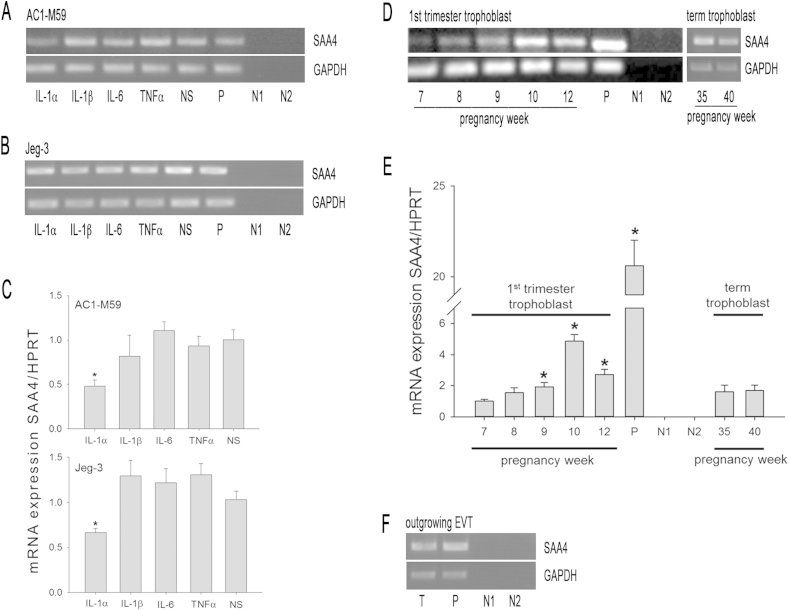

RT-PCR (Fig. 1A/B) and qPCR analysis (Fig. 1C) reveals that SAA4 mRNA expression in AC1-M59 cells as well as in its parental cell line Jeg-3 (Fig. 1A/B) is not altered by IL-1β, IL-6, and TNFα treatment. However, IL-1α significantly decreased SAA4 mRNA expression in both cell lines (Fig. 1C). This observation, as well as similar data obtained in non-differentiated human mesenchymal stem cells and human osteosarcoma cell lines (using RT-PCR [19]) does not confirm the constitutive character of apolipoprotein SAA4 [6,7] in general.

Fig. 1.

RT-PCR and qPCR analysis for SAA4 mRNA expression in non-stimulated and cytokine-stimulated trophoblast cells: AC1-M59 and Jeg-3 cells were stimulated with different cytokines (10 ng/ml) for 24 h (A–C). RNA was isolated from both cell lines (A–C) as well as from cell preparations from first trimester and term trophoblast cells at indicated pregnancy weeks (D, E) as well as outgrowing EVT cells from placental villi from first trimester placentas (F). Then RNA was reverse transcribed, and cDNA was amplified using specific forward and reverse oligonucleotide primers (Supplementary Table I). RT-PCR products were separated on 1.5% agarose gels. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping gene. qPCR was performed from reverse-transcribed RNA isolated from non-stimulated and cytokine-stimulated AC1-M59 and Jeg-3 cells (C) and first trimester and term trophoblast cells (E) using specific primers (Supplementary Table II) for SAA4 and HPRT (used as a housekeeping gene). NS (non-stimulated); P (positive control: RNA was isolated from human hepatocellular carcinoma HUH-7 cells, diluted 1:20 in F); N1 (negative control, RNA template: negative controls were done for all samples); N2 (negative control, water template). T = EVT. One representative experiment out of three is shown. Values (C and E) are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4). (C) = *p ≤ 0.05 vs. non-stimulated cells; (E) *p ≤ 0.05 vs. first trimester trophoblast cells isolated from pregnancy week 6 (set as 1; x-fold expression of SAA4/HPRT mRNA is given on the Y-axis in (C) and (E)).

High SAA4 mRNA expression in human colon adenocarcinoma [10,23] and ovarian carcinoma [11] suggests a possible role of SAA4 in tumorigenesis and invasion as previously reported for SAA1/2 [24,25]. This seems likely, as the adhesion motif present in the N-terminal region of SAA1/2 that mediates binding to extracellular matrix components and cell invasion, is highly homologous to that present in SAA4. One of the hallmarks of first trimester placental development is invasion of uterine tissue by fetal trophoblast cells. Thus, SAA4 expression was studied in invasive trophoblast cells. While expression of SAA4 transcripts is low during early placental development (weeks 7–9), expression levels are increased at later first trimester pregnancy weeks but decreased at term pregnancy stages (Fig. 1D). Data obtained from qPCR analyses (Fig. 1E) confirmed results obtained with RT-PCR (Fig. 1D); highest SAA4 mRNA expression was found at week 10 and 12; however, at later pregnancy stages (week 35 and 40) SAA4 mRNA levels were similar as observed in early pregnancy weeks. Furthermore, SAA4 mRNA expression was also found in preparations of isolated outgrowing first trimester EVT cells (Fig. 1F).

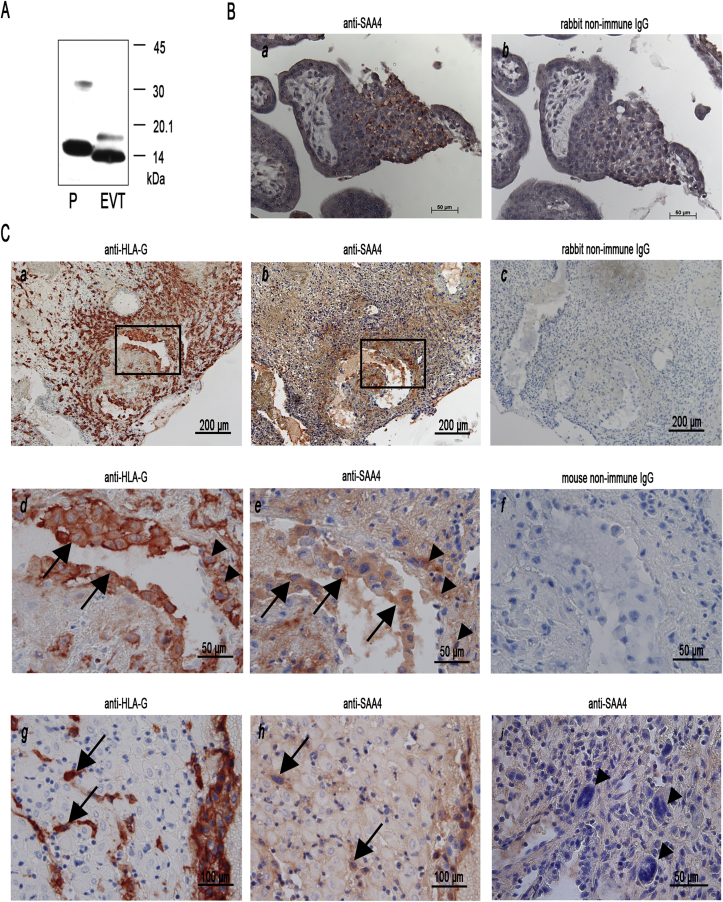

Next, we tried to identify SAA4 protein in human placental tissue using an antibody (raised against the C-terminal portion [that differs from SAA1/2] of SAA4 [21]). Two immunoreactive bands corresponding to approximately 14 kDa (non-glycosylated) and a less intensive 19 kDa (glycosylated) protein, as reported for liver-derived human SAA4 [5,7], were identified by Western-blot in outgrowing EVT cells (Fig. 2A). However, no immunoreactive signals for SAA4 were detected in AC1-M59 or Jeg-3 cells under non-stimulated or cytokine-stimulated conditions (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

SAA4 protein expression in trophoblast cells from first trimester and term placenta: (A) Outgrowing EVT cells were isolated, lysed and 50 μg of total protein was subjected to Western-blot analysis using anti-human SAA4 as primary antibody [21]. As a positive control (P) human non-glycosylated SAA4 ([expressed in E. coli] containing an N-terminal His6-tag and an enterokinase cleavage site [21]) was detected as a monomeric (approximately 15.5 kDa) or dimeric (31 kDa) protein. One representative Western-blot is shown. (B) Paraffin sections of placental specimens from first trimester placental villi and (C) trophoblast-invaded decidua basalis were stained with anti-human SAA4 antiserum (Ba, Cb,e,h,i) or with anti-human HLA-G antibody (Ca,d,g) as a marker for trophoblast cells. Control experiments were performed with non-immune rabbit IgG (Bb and Cc) or non-immune mouse IgG (Cf). To detect antibody binding labelled polymer and 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole was used. The indicated areas in (Ca) and (Cb) (demonstrating part of trophoblast-invaded spiral artery) are shown at higher magnification as (Cd) and (Ce). Arrows in (Cd) and (Ce) point towards intraluminal trophoblast cells while arrowheads point towards intramural trophoblast cells positive for SAA4. Arrows in (Cg) and (Ch) point towards interstitial trophoblast cells positive for SAA4. The arrowheads in (Ci) represent multinucleated trophoblast giant cells negative for SAA4. The respective bar size is indicated in (B) and (C).

Immunohistochemical staining revealed the presence of SAA4 in cell columns of first trimester placental tissue representing potentially invasive EVT cells (Fig. 2Ba). In the proliferative zone of cell columns near the basement membrane towards the villous stroma, SAA4 was barely detectable. Interestingly, the more pronounced the invasive character of trophoblast cells, the more pronounced is SAA4 expression (Fig. 2Ba). Areas within the decidua, which were invaded by trophoblast cells (Fig. 2Ca), show positivity for SAA4 (Fig. 2Cb). SAA4 expression was detected in different EVT cell populations that had already invaded the decidua basalis, such as intramural trophoblast cells replacing the walls of spiral arteries (Fig. 2Cd and e), intraluminal trophoblast cells plugging the lumina of spiral arteries (Fig. 2Cd and e), and interstitial trophoblast cells (Fig. 2Cg and h), respectively. However, multinucleated trophoblast giant cells, a subpopulation representing the terminally differentiated sessile endpoint of invading trophoblast cells [26], showed no staining for SAA4 (Fig. 2Ci). Also glandular epithelial cells of the decidua were negative for SAA4 (Supplementary Fig. I). To verify the trophoblast nature of these cells an antibody recognizing HLA-G (expressed only by extravillous trophoblast and choriocarcinoma cells) was used on serial sections (Fig. 2Ca, d and g).

Here we present first evidence of a pronounced expression of SAA4, so far considered as a protein of “unknown” function, in first trimester placental tissues. SAA4 expression in invasive trophoblast cells suggests a likely role of this apolipoprotein during invasion. The underlying mechanisms as reported for acute-phase SAA [25] are currently under investigation.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

Supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) DK-MCD W1226, P19074 and SFB-LIPOTOX F3007).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Uhlar C.M., Whitehead A.S. Serum amyloid A, the major vertebrate acute-phase reactant. Eur J Biochem. 1999;265(2):501–523. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malle E., Steinmetz A., Raynes J.G. Serum amyloid A (SAA): an acute phase protein and apolipoprotein. Atherosclerosis. 1993;102(2):131–146. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(93)90155-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen L.E., Whitehead A.S. Regulation of serum amyloid A protein expression during the acute-phase response. Biochem J. 1998;334(Pt 3):489–503. doi: 10.1042/bj3340489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malle E., De Beer F.C. Human serum amyloid A (SAA) protein: a prominent acute-phase reactant for clinical practice. Eur J Clin Invest. 1996;26(6):427–435. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1996.159291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Beer M.C., Yuan T., Kindy M.S., Asztalos B.F., Roheim P.S., de Beer F.C. Characterization of constitutive human serum amyloid A protein (SAA4) as an apolipoprotein. J Lipid Res. 1995;36(3):526–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamada T., Kluve-Beckerman B., Kuster W.M., Liepnieks J.J., Benson M.D. Measurement of serum amyloid A4 (SAA4): its constitutive presence in serum. Amyloid. 1994;1(2):114–118. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitehead A.S., de Beer M.C., Steel D.M., Rits M., Lelias J.M., Lane W.S. Identification of novel members of the serum amyloid A protein superfamily as constitutive apolipoproteins of high density lipoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(6):3862–3867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ren Y., Wang H., Lu D., Xie X., Chen X., Peng J. Expression of serum amyloid A in uterine cervical cancer. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:16. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-9-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen C.L., Lin T.S., Tsai C.H., Wu C.C., Chung T., Chien K.Y. Identification of potential bladder cancer markers in urine by abundant-protein depletion coupled with quantitative proteomics. J Proteomics. 2013;85:28–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutfeld O., Prus D., Ackerman Z., Dishon S., Linke R.P., Levin M. Expression of serum amyloid A, in normal, dysplastic, and neoplastic human colonic mucosa: implication for a role in colonic tumorigenesis. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54(1):63–73. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5A6645.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urieli-Shoval S., Finci-Yeheskel Z., Dishon S., Galinsky D., Linke R.P., Ariel I. Expression of serum amyloid A in human ovarian epithelial tumors: implication for a role in ovarian tumorigenesis. J Histochem Cytochem. 2010;58(11):1015–1023. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2010.956821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovacevic A., Hammer A., Sundl M., Pfister B., Hrzenjak A., Ray A. Expression of serum amyloid A transcripts in human trophoblast and fetal-derived trophoblast-like choriocarcinoma cells. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(1):161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urieli-Shoval S., Cohen P., Eisenberg S., Matzner Y. Widespread expression of serum amyloid A in histologically normal human tissues. Predominant localization to the epithelium. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46(12):1377–1384. doi: 10.1177/002215549804601206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson P.M., Husby G., Natvig J.B., Anders R.F., Linder E. Identification in human placentae of antigenic activity related to the amyloid serum protein SAA. Scand J Immunol. 1977;6(4):319–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1977.tb00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poehlmann T.G., Fitzgerald J.S., Meissner A., Wengenmayer T., Schleussner E., Friedrich K. Trophoblast invasion: tuning through LIF, signalling via Stat3. Placenta. 2005;26(Suppl. A):S37–S41. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wadsack C., Hammer A., Levak-Frank S., Desoye G., Kozarsky K.F., Hirschmugl B. Selective cholesteryl ester uptake from high density lipoprotein by human first trimester and term villous trophoblast cells. Placenta. 2003;24(2–3):131–143. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Funayama H., Gaus G., Ebeling I., Takayama M., Füzesi L., Huppertz B. Parent cells for trophoblast hybridization II: AC1 and related trophoblast cell lines, a family of HGPRT-negative mutants of the choriocarcinoma cell line Jeg-3. Trophobl Res. 1997;10:191–201. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaus G., Funayama H., Huppertz B., Kaufmann P., Frank H.G. Parent cells for trophoblast hybridization I: Isolation of extravillous trophoblast cells from human term chorion laeve. Trophobl Res. 1997;10:181–190. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kovacevic A., Hammer A., Stadelmeyer E., Windischhofer W., Sundl M., Ray A. Expression of serum amyloid A transcripts in human bone tissues, differentiated osteoblast-like stem cells and human osteosarcoma cell lines. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103(3):994–1004. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossmann C., Rauh A., Hammer A., Windischhofer W., Zirkl S., Sattler W. Hypochlorite-modified high-density lipoprotein promotes induction of HO-1 in endothelial cells via activation of p42/44 MAPK and zinc finger transcription factor Egr-1. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;509(1):16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hrzenjak A., Artl A., Knipping G., Kostner G., Sattler W., Malle E. Silent mutations in secondary Shine-Dalgarno sequences in the cDNA of human serum amyloid A4 promotes expression of recombinant protein in Escherichia coli. Protein Eng. 2001;14(12):949–952. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.12.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gauster M., Siwetz M., Huppertz B. Fusion of villous trophoblast can be visualized by localizing active caspase 8. Placenta. 2009;30(6):547–550. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michaeli A., Finci-Yeheskel Z., Dishon S., Linke R.P., Levin M., Urieli-Shoval S. Serum amyloid A enhances plasminogen activation: implication for a role in colon cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;368(2):368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malle E., Sodin-Semrl S., Kovacevic A. Serum amyloid A: an acute-phase protein involved in tumour pathogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66(1):9–26. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8321-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandri S., Urban Borbely A., Fernandes I., Mendes de Oliveira E., Knebel F.H., Ruano R. Serum amyloid A in the placenta and its role in trophoblast invasion. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e90881. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kemp B., Kertschanska S., Kadyrov M., Rath W., Kaufmann P., Huppertz B. Invasive depth of extravillous trophoblast correlates with cellular phenotype: a comparison of intra- and extrauterine implantation sites. Histochem Cell Biol. 2002;117(5):401–414. doi: 10.1007/s00418-002-0396-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.