Abstract

Monitoring the metabolic activity of cells in automated culture systems is one of the key features of micro-total-analysis systems. We have developed a microfluidic device that allows us to trap single cardiac myocytes (SCM) in sub-nanoliter volumes and incorporates amperometric glucose sensing electrodes with working areas of 0.002 mm2 to measure the glucose consumption of SCM. The miniaturized planar glucose electrodes were fabricated by spin coating platinum electrodes on glass substrates with a glutaraldehyde/enzyme solution and a protective Nafion membrane. The glucose electrodes demonstrate a high enzymatic activity characterized by an apparent Michaelis-Menten constant of 7.52±0.18mM and a sensitivity of ~33.8mA/M·cm2 and ~13.2mA/M·cm2 at glucose concentration from 0–6mM and 6–20mM in Tyrode’s solution, respectively. The response time of the glucose electrodes was between 5 and 15s, and the sensitivity of the electrodes did not degrade over a period of 8 weeks. A replica molded polydimethylsiloxane microfluidic device with a sub-nanoliter sensing volume was sealed to the glass substrate and aligned with the glucose microelectrodes. SCM can be trapped in the sensing volume above the glucose electrodes to measure the glucose consumption over time. The average glucose consumption of SCM was 0.211±0.097mM/min (n=7) in Tyrode’s solution with 5mM of glucose.

Keywords: glucose sensor, glucose oxidase, spin coating deposition, microfluidic device, cardiac myocytes

1. Introduction

Micro-total-analysis-system (μ-TAS) technologies are becoming increasingly established and have had a substantial impact on bio-analytical applications (West et al., 2008). μ-TAS systems have been developed to monitor the metabolic activity of cells in automated microfluidic-based culture systems (Huang and Lee, 2007; Tanaka et al., 2007). However, adding sensing to μ-TAS and scaling the technologies to single cells remains challenging. One strategy is to trap single cells in confined volumes equipped with miniature electrochemical sensing electrodes (Ges et al., 2008). The metabolic activity of single cells can be monitored by measuring the acidification rate in the extracellular environment (Ges and Baudenbacher, 2008; Werdich et al., 2004). A decrease in pH occurs as acidic metabolites build up the extracellular environment (Baxter et al., 1994; Eklund et al., 2003; Ges et al., 2007). In order to detect metabolic pathway switching and utilize the technology for cell based toxin or pathogen detection or high throughput drug screening applications, the sensing capabilities must be extended to include measuring glucose consumption rates.

In recent years, many different types of glucose-sensing systems, such as enzyme coated, amperometric (Lapierre et al., 1998; Shan et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2007), potentiometric (Liao et al., 2007), optical (Pasic et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008), Quartz Crystal Microbalance (Deng et al., 2007) and resistive transduction schemes (Soldatkin et al., 1994), have been developed. Amperometric glucose sensors utilize entrapped glucose oxidase (GOx) and sense oxygen or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) concentration to measure glucose concentration (Updike and Hicks, 1967). The hydrogen peroxide quantification is typically based on the electrochemical oxidation of H2O2 on platinum electrodes, on which the GOx is immobilized. There are numerous possibilities for immobilizing GOx on electrodes, ranging from applying the enzyme solution manually, screen printing, and photochemical deposition to entrapment of the enzyme during electropolymerization of pyrole (Eklund et al., 2006; Nakajima et al., 2006; Suzuki, 2000); however, not all methods are suited for the fabrication of micron–sized, highly sensitive electrodes.

In this paper, we describe the design and fabrication of a microfluidic device suitable to trap SCM and integrate miniature amperometric glucose sensing electrodes. The glucose sensors are incorporated into a sub-nanoliter sensing volume and utilized to measure the glucose consumption rates from SCM. The described sensors are highly stable, reproducible, provide high sensitivities in multiple, commonly used cell culture media and can be integrated into more complex μ-TAS for metabolic pathway monitoring. The device architecture can be easily extended to multiple detection volumes allowing for high throughput measurements.

2. Reagents and Materials

Titanium (99.95%) and platinum (99.95%) were purchased from Goodfellow Corp. Triton X-100 was purchased from Acros, and D –(+) glucose (99.5%), glucose oxidase (Aspergillus niger), bovine serum albumin and 25% solution of glutaraldehyde came from Sigma. Nafion® from Alfa Aesar and universal pH buffers from VWR Scientific. The salts used for the Tyrode’s solution (potassium chloride, sodium chloride, magnesium chloride, sodium phosphate, sodium bicarbonate) were supplied by Fisher Scientific. RPMI-1640 buffer was from Molecular Device Corp. DMEM were purchased from Mediatech, Inc., All chemicals were used as received. Double-distilled water was used for the preparation of all solutions.

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) elastomer composed of prepolymer and curing agent (Sylgard 184 kit, Dow Corning) was purchased from Essex Chemical.

3. Instrumentation

Thin film metal electrodes were fabricated on microscope glass substrates using e-beam vacuum evaporation of Ti and Pt from carbon crucible liners. The deposition rate and the thickness of the films were monitored with a controller MDC-360 (Maxtek, Inc.).

A spin processor (WS-400B-6NPP-Lite) with digital process controller (Laurell Technologies Corp.) was used for the deposition of the glucose sensor components (glucose oxidase, Nafion).

All electrochemical experiments were performed with potentiostat models CHI660B or CHI1030 produced by CH Instruments, Austin, TX. A three-electrode configuration was used for calibration and glucose consumption measurements on SCM. The counter electrode was either a Pt wire with a diameter of 1mm for the calibration experiments in the beaker or a thin Pt film for experiments in a microfluidic device. In all experiments a Dri-Ref-450 from WPI, Inc. was used as reference electrode (diameter 0.45mm).

Fluidic flow visualization was performed using colored solutions and an inverted microscope (AXIOVERT 25CFL) in combination with a color CCD camera (KP-D20BU, Hitachi). The fluidic flow was controlled and maintained using a microsyringe pump controller MICRO-4 (WPI).

4. Experimental

In order to measure the glucose consumption of SCM, we combined a planar microfabricated functionalized sensor array with a microfluidic device, which allows us to confine the myocytes in a working volume of 0.36nL. The fabrication steps of the combined device can be broken down into the following steps: deposition and patterning of thin film electrodes; functionalizing the electrodes to form the glucose sensing elements using spin coating; replica molding of PDMS microfluidic devices.

4.1. Thin film conducting electrodes

The planar thin film metal electrodes were fabricated on microscope glass slides which were cut into small sections of 25×25mm2. The glass substrates were thoroughly cleaned prior to deposition. The planar metal electrodes consist of two layers: a Ti adhesion layer (10nm) and a Pt layer (100nm). Thin film electrodes were deposited by e-beam vacuum evaporation of Ti and Pt in a single process without breaking vacuum. The deposition rate and the thickness of the films were monitored by a quartz crystal microbalance deposition controller. The miniature electrodes were fabricated by patterning the Ti–Pt films using a standard photolithography process with a 1 μm-thick photoresist (NR7-1000P). The unprotected Ti–Pt film was removed by ion beam etching

4.2. Glucose electrode fabrication

The enzyme solution to fabricate glucose sensitive electrodes was prepared with minor modifications to the procedure published by Eklund (Eklund et al., 2004). In our protocol, the glucose oxidase (GOx) film solution was prepared by dissolving 2.5mg of GOx and 25mg of BSA in 250μL of 1mM PBS containing 0.02% v/v Triton X-100. After the BSA and GOx were completely dissolved, 15μL of 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution was added and thoroughly mixed using a Vortexer for 10min. Different types of polymer membranes were used to protect the GOx and improve the long-term characteristics of the sensor. In our investigation we used Nafion membranes because of their excellent glucose and oxygen diffusivity and biocompatibility (Koudelka et al., 1989). The enzyme layer was deposited onto the microfabricated metal electrodes by spin coating. The enzyme solution (100μL) was pipetted onto the substrate. The substrate was then spun at 1500rpm for 30s using a spin coater. A typical thickness of the glucose oxidase film was ~0.4μm. After spin coating, the GOx films were dried at room temperature for 1 hour. Nafion polymer membranes (~0.4μm) were also deposited by spin coating. In order to characterize the miniature glucose electrodes in a beaker, we partially covered the electrodes with a thin PDMS membrane (~100μm), exposing a working area of 50×500μm2. The biosensor devices were stored at 4°C before use.

4.3. PDMS microfluidic network

The microfluidic network was fabricated from PDMS by replica molding, using photoresist on a silicon wafer as a master. The PDMS polymer was prepared by mixing PDMS pre-polymer with curing agent in a 10:1 ratio by weight. The master was fabricated by spinning a 20μm thick layer of photoresist (SU-8 2025) on a silicon wafer and by exposing it to UV light through a metal mask. The master was placed in a Petri dish, which was filled to a height of approximately 1cm with PDMS polymer and cured in an oven for 4 hours at 70°C. After curing, the elastomer was mechanically separated from the master and cut into discrete devices. The PDMS microfluidic device was manually aligned relative to the glucose sensitive electrodes with a stereo microscope. The PDMS device was sealed to the glass substrate by auto-adhesion, and stabilized with a mechanical clamp (Fig. 1d). For cell manipulation we controlled the syringes connected to the output and control port by hand. For precise flow control we incorporated miniature mechanical screw valves into the microfluidic devices (Ges et al., 2008). Our design allowed us to place two valves within a footprint of 6×8mm2 in close proximity to the 0.36 nL sensing volume (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

(a) Schematic overview of a NanoPhysiometer to measure glucose consumption from single cardiac myocytes in sub-nanoliter volumes: (A) micro-fluidic channels network; (B) microelectrode array. Only two electrodes (counter, working) of the seven shown are in contact with the microfluidic network at any one time. (b) Enlarge view of microelectrodes in the detection volume: (1) mechanical screw valve; (2) Ag/AgCl reference electrode; (3) glucose sensor; (4) Pt counter electrode. (c) Combined multielectrode sensor array (5) and PDMS microfluidic (6) device. (d) Picture of the complete assembly with clamping mechanism (7), which ensures mechanical stability and reliable seal between PDMS microfluidic device and glass substrate with the thin film glucose sensors; (8) - external Ag/AgCl reference electrode diam. 0.45mm.

4.4. Single cell isolation

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of Avertin solution (5mg Avertin per 10g body weight, T48402, Sigma-Aldrich) containing heparin (3mg/10ml, H9399, Sigma-Aldrich). The heart was rapidly excised and placed into ice-cold Ca2+ -free and glucose-free Hepes-buffered Tyrode’s solution (TS). The TS contained (in mM): NaCl–140, KCl–4.5, MgCl2–0.5, NaH2PO4–0.4, NaHCO3–10, Hepes–10. The pH of all solutions was adjusted to 7.4 using NaOH. The aorta was cannulated and the heart was perfused with TS at room temperature for 10min to stop contractions. The perfusion was then switched to TS containing 10mM CaCl2 with collagenase (178U/ml, CLS2, Worthington Biochemical) and protease (0.64U/ml, P5147, Sigma-Aldrich) for 12 minutes at 37°C. Tissues from the atria and aorta were discarded. The remaining ventricular tissue was coarsely minced and placed into T solution containing 0.5mM Ca2+. Myocytes were dissociated by gentle agitation and used within 3 hours after isolation.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Characterization of glucose sensor

Here we describe the fabrication of a glucose sensor to measure the glucose consumption rate of a SCM in a confined extracellular space with an active sensing area of the glucose electrode comparable to the cell size. Conventional methods of drop deposition are not suited for our purpose because it is practically impossible to achieve a uniform thickness of the GOx film. The spin coating of glucose oxidase onto macrosurfaces (Kimura et al., 1989) or to fabricate permeable membranes (Chang et al., 2005; Soldatkin et al., 1994) is described in the literature.

The functionalizing of the metal electrodes with the different films was conducted in a clean room. The detailed protocol for the deposition consists of the following steps: cleaning the glass substrate with Pt electrodes using pressurized dry nitrogen; spin coating deposition of GOx at 1500rpm and 30s; 1 hour drying at room temperature; spin coating deposition of protective polymer membrane (Nafion); 0.5 hours drying at room temperature. Using this approach we obtained GOx and Nafion films of high uniformity. The deviations in the thickness of the films were less than 3%.

The thickness of the coatings had a strong influence on the characteristics (sensitivity, stability, response time) of the glucose sensor. We fabricated devices with different thickness of GOx and Nafion films to optimize the properties of the glucose sensors. Based on our optimization, we found that the thickness for the GOx and Nafion films should be 0.4÷0.6 μm and 0.4÷0.5 μm, respectively.

Glucose oxidase is one of the most extensively studied enzymes for the fabrication of glucose biosensors. The glucose sensors on the base of GOx have a high selectivity and sensitivity, a wide range over which the sensitivity is constant, operation at room temperature and a low cost of sensor fabrication. The detection of glucose with an enzyme-electrode is based on the electrochemical detection of H2O2, which is produced during the enzyme-catalyzed oxidation of glucose by dissolved oxygen. The following chemical reactions summarize the transducing principle (Chen et al., 2006; Deng et al., 2007). First, the GOx oxidizes the glucose and produces gluconic acid and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2).

| (1) |

Then, the hydrogen peroxide is further oxidized.

| (2) |

The concentration of peroxide can be determined by measuring a current generated between the working and the counter electrode in this amperometric detection scheme. To demonstrate the sensor performance under realistic biological conditions, we measured the sensor sensitivity in common cell growth media (DMEM, RPMI-1600 and Tyrode’s) and compared the properties of spin coated glucose sensors with the characteristics of the same sensor in standard phosphate buffer solution. For this purpose the glucose electrodes were calibrated in a glass beaker containing 25mL of the cell growth media. A DRI-Ref 450 (diam. 0.45mm) was used as a reference electrode, and a bare Pt thin film microelectrode was used as a counter electrode. The glucose electrodes were set at +0.6V versus an Ag/AgCl reference electrode to oxidize hydrogen peroxide. After the current reached a steady baseline, the glucose concentration was increased in steps of 2mM. The current-time response of a typical glucose sensor during the successive additions of glucose to the different cell culture media and PBS is shown in Fig. 2a. The response times are summarized in Table 1 and were on the order of 5–15s. The current generated at the glucose electrode was stable in all solutions and practically did not change during the time course of the measurement. The calibration curves for our glucose sensors in different cell culture media and PBS are presented in Fig. 2b. The current generated by the enzyme electrode increased monotonously with the increase in glucose concentration. Fig. 2b shows that there are two regions (I and II) in which the current response versus glucose concentration can be linearized. The sensitivity for Tyrode’s solution was ~ 0.85×10−8A/mM and ~0.34×10−8A/mM in region I (0÷6mM) and in region II (6–20mM), respectively. The sensitivities of the glucose sensor for the different culture media and PBS in regions I and II are summarized in Table 1. The sensitivities of the glucose electrodes used in our experiments on single cardiac myocytes were typically ~13mA/M·cm2 in region II for Tyrode’s solution.

Fig. 2.

(a) Current-time curves recorded from the glucose sensors during calibration through the successive addition of 2mM glucose in four different cell culture media in beaker experiments. 1–DMEM; 2–RPMI-1640; 3–Tyrod’s solution (pH7.4); 4–Phosphate buffer solution (pH7). (b) Current as a function of glucose concentration in four different cell culture media. 1–DMEM; 2–RPMI-1640; 3–Tyrod’s solution (pH7.4); 4–Phosphate buffer solution (pH7). The sensitivity can be linearly approximated in region I (glucose concentration of < 6mM) as ~0.85×10−8A/mM and in region II (glucose concentration of > 6mM) as 0.34×10−8A/mM (for Tyrod’s solution).

Table 1.

The main characteristics of spin coated glucose sensors in different cell growth media

| Cell growth media | Sensitivity I region/II region mA/M·cm2 | Response time s | Lifetime month | Apparent Michaelis-Menten constant mM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMEM | 13.9/6.4 | ~ 20 | ~0.5 | 3.13±0.14 |

| RPMI-1680 | 32.1/9.8 | 10 ÷ 15 | ~2 | 8.40±0.47 |

| Tyrode’s | 33.8/13.2 | 5 ÷ 10 | >3 | 7.51±0.18 |

| PBS | 40.1/14.8 | 5 ÷ 10 | >3 | 6.83±0.50 |

The apparent Michaelis-Menten constant ( ), which characterizes the enzyme-substrate kinetics, was estimated using the Lineweaver-Burk equation (Deng et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2007), to be for Tyrode’s solution. This value agrees well with values reported in the literature for glucose sensors on the basis of Nafion coated GOx functionalized electrodes (4.3mM in (Zhao et al., 2006); 5.47mM in (Deng et al., 2007); 14.91mM in (Ozoemena and Nyokong, 2006).

The long-term stability of our spin coated miniaturized glucose sensors were tested by continuous monitoring the steady-state currents in four different solutions at glucose concentration of 6 and 8mM at room temperature over time. As shown in Fig. 3a the steady state current for the three solutions (RPMI, Tyrode’s and PBS) did not change significantly over a one hour period, which is sufficient to monitor the metabolic activity of SCM. In contrast, a small constant signal drift was observed in the DMEM solution. However, the drift is small and could be taken into account in specific experiments. We evaluated the shelf life of our glucose sensors by recording three calibration curves with at least ten measurement points every three days over an extended period of time. In between experiments, the electrodes were stored dry in container at room temperature. Fig. 3b show the sensitivities of the glucose sensors for region I and II for 3 different glucose sensitive electrodes (E4, E5, E8) over a period 10 weeks obtained in Tyrode’s solution. During this investigation, we conducted about 100 calibrations with each electrode without a significant decrease in sensitivity. The tested sensors were fabricated on one substrate under identical conditions. No appreciable loss in sensor sensitivity was observed for periods of about three month.

Fig. 3.

(a) Stability of the current generated by the glucose sensor over time in four different cell culture media (1–DMEM; 2–RPMI-1640; 3–Tyrod’s solution (pH7.4); 4–Phosphate buffer solution (pH7)) with 6 and 8mM glucose concentration. (b) Investigation of long time stability of the sensitivity of the glucose sensor for region I and II for 3 different glucose sensitive electrodes (E4, E5, E8) in Tyrod’s solution.

5.2. Properties of glucose sensors in microfluidic environment

To measure the metabolic activity of SCM in a confined extracellular space of comparable size we integrated the glucose sensor array into a microfluidic device (NanoPhysiometer). The layout and an image of a NanoPhysiometer to measure glucose consumption from SCM in sub-nanoliter volumes are shown in Fig. 1. The device consists of a PDMS microchannel network auto-adhered to a glass substrate with a microfabricated array of platinum electrodes functionalized with GOx. A clamp was used to provide the mechanical stability. The glass substrate typically had 7 Pt electrodes. Four of the electrodes were functionalized as glucose sensors. Three electrodes remained bare and were used as counter electrodes. The glucose sensitive electrode (labeled (3)) was aligned with the cell trap volume in the microfluidic devices and the input port (Fig. 1a,b) with the bare Pt thin film used as counter electrode (labeled (4)). The external reference electrode (2) was placed in the input port. During the measurement of glucose consumption the mechanical microvalves (1) were closed to eliminate the influence of residual fluid flow on the signal.

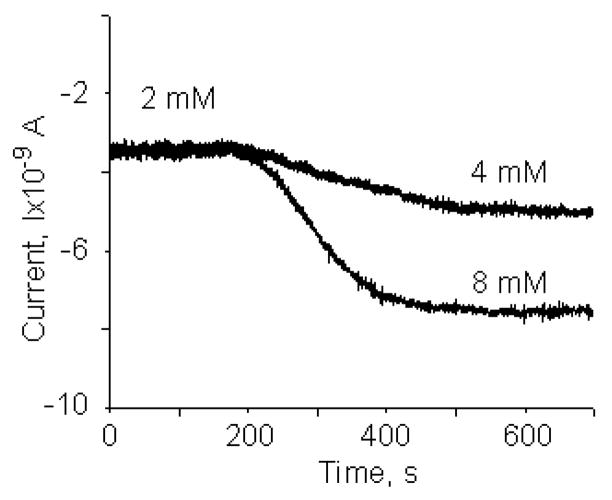

In order to validate the performance of the glucose electrodes (100×500μm2) in a microfluidic environment, we filled the microfluidic channel (width ~40μm) with Tyrode’s solution with a glucose concentration of 2mM. We then inserted tubing filled with Tyrode’s solution containing 8mM glucose into the input port. Electrochemical measurements for glucose concentration showed a stable response of the current signal, as shown in Fig. 4. After ~5min, the syringe pump was turned on and Tyrode’s solution (8mM glucose) with a flow rate of 2nL/min was forced through the input channel. During the period from 200s to 400s the current increases. After 400s we obtained a stable current representing the concentration of 8 mM of glucose. The transition period is a result of the sensor response and a concentration gradient in the microfluidic channel. The experiments were repeated with a change in glucose concentration from 2 to 4mM in Tyrode’s solution and are also shown in Fig. 4. We computed a sensitivity of glucose sensor in the microfluidic environment of 25.2mA/M·cm2 (region I) and 13.8mA/M·cm2 (region II). These sensitivity values as well as the Signal to Noise Ratios (SNR) are comparable to beaker experiments. Furthermore, the data allowed us to compute the smallest detectable change in Glucose concentration to be 1.69 mM at a SNR of 3 and a bandwidth of 10Hz. The SNR could be significantly improved by reducing the bandwidth.

Fig. 4.

Calibration of the glucose sensor (100×500μm2) in the microfluidic channel (width ~40μm) with Tyrod’s solution of different glucose concentrations (2 and 4mM; 2 and 8mM). The flow rate during calibration was 2nL/min.

5.3 Glucose consumption measurements from single cardiac cells in sub-nL volume

In order to measure the glucose consumption from single cardiac myocytes, we designed a microfluidic device (NanoPhysiometer), which allows us to trap SCM above our miniature thin film glucose electrodes in a volume of 360pL. A layout of the configuration and the assembled device are shown in Fig. 1. A concentrated cell suspension (6–8 μl) was added to the input reservoir using a syringe with a plastic needle. The input port is connected to the 360pL cell trap volume through the cell input channel (Fig. 5A). By applying a pressure gradient to the output and control ports, the cardiac cells move from the reservoir along the input channel toward the cell trap volume. After trapping a SCM, we closed the mechanical valves to block the output and control channels (Fig. 1a) to suppress residual flow. The results of our measurements to quantify the glucose consumption from a SCM in the sub-nanoliter (0.36nL) volume in Tyrode’s solution are shown in Fig. 5A and 5B. In the measurements shown in Fig. 5A, we used spin coated glucose sensitive electrodes (GOx ~ 0.4mm, Nafion ~ 0.4mm on Pt electrodes) with dimensions of 40×100 μm2. Data from the initial setting of the amplifiers and the time required to trap cell in the sensing volume are not shown. In Fig. 5A three regimes can be identified. In the first (R1) period the current declines at a constant rate, which represents a reduction of the glucose concentration. Taking into account the sensitivity of the glucose electrode (region II, 4÷10mM (Fig. 4)), which was 0.55·10−9A/mM, we estimated that the change in the glucose concentration was 0.91mM over a time period of 300s. After removal of the cell at the beginning of period RII (Fig. 5A(b)), we observed a flattening in the current time plot (Fig. 5A, region RII) and the current (glucose concentration) remained constant, demonstrating that the consumption of glucose by the electrode is negligible compared to the consumption by the myocyte. During period RIII, the cardiac cell was moved back into the cell trap volume using a negative pressure in the control port. After closing the mechanical valves and a stabilization period (2÷3min) we began to record and repeat the measurement of the glucose consumption rate. We observed a linear decrease of the anodic current over time which corresponds to the reduction of the glucose concentration in the sensing volume of the NanoPhysiometer of 1.45mM over a time period of 600s. From the data, we computed the rate of glucose consumption as 0.182mM/min and 0.145mM/min for region RI and region RIII, respectively.

Fig. 5.

(A) Measurements of the glucose consumption from single cardiac myocyte in a 0.36nL volume in Tyrode’s solution (10mM glucose, 0.5mM Ca2+). Region R1 and R3 – cardiac myocyte in the detection volume (image (a)). Region R2 – cardiac myocyte removed from the detection volume (image (b)). Glucose sensor (GOx~0.4 μm and Nafion~0.4 μm thick) with a sensitive area of 40×100 μm2. 1–cell input channel; 2–output channel; 3–cell trap volume (0.36nL); 4–cardiac myocyte; 5–glucose sensor. (B) Current over time recorded from the glucose sensor (GOD~0.53 μm; Nafion~0.46 μm; dimension of sensor working area ~100×40 μm2) in Tyrode’s solution without glucose (1–3). The measurements of glucose consumption from different single cardiac myocytes (4–6) in the subnanoliter (0.36nL) volume in Tyrode’s solution (10mM glucose, 0.8mM Ca2+). The inset shows a glucose consumption rate (GCR) measurement of wild type cardiac myocytes. For cardiac myocytes we measured an average GCR 0.211±0.097mM/min (n=7).

We conducted a series of experiments with cardiac myocytes to determine the metabolic activity of single cardiomyocytes in sub-nanoliter confined volumes statistically. The data are shown in Fig. 5B. The glucose sensors used in these experiments had the following characteristics: thickness of GOx film ~0.53 μm; thickness of Nafion film ~ 0.46 μm; dimensions of the working area 100×40 μm2; sensitivity ~0.24×10−4A/mM·cm2. The baseline recordings of the current generated by the glucose sensor in the NanoPhysiomter in Tyrode’s solution without glucose and cells are shown in Fig. 5B in traces 1–3. After the initial settling period of 0–80s, the current achieves a stable value and almost does not change over the time period of an experiment. Measurements of glucose consumption from three different SCM in the sub-nanoliter volume in Tyrode’s solution (10mM glucose; 0.8mM Ca2+) are shown in Fig. 5B in traces 4–6. After an initial settling of the amplifiers and non linear decrease of current over time the glucose consumption is approximated constant. This constant decline was used to characterize the metabolic activity of cardiac cells and to compute the glucose consumption rate (GCR). We calculated GCR as the rate of current change during the time period from 100s to 400s. The inset of Fig. 5B shows GCR measurements of single cardiac myocytes. We measured an average GCR 0.211±0.097mM/min (n=7)

6. Conclusions

We combined electrochemical glucose sensors and microfluidic technologies to fabricate a NanoPhysiometer, which can be utilized to measure the glucose consumption of single cardiac cells in Tyrode’s solution confined in a restricted extracellular space. The microsize (50×500μm2) glucose sensors have a high sensitivity (~13mA/M·cm2 in the range of 6–20mM), response times of ~5–15s, a shelf life time of ~2 months with a Michaelis-Menten kinetics characterized by a and were fabricated using spin coating to deposit glucose oxidase and Nafion on Pt thin film electrodes. We demonstrated a dependence of the sensitivity on the type of cell growth media used (DMEM, RPMI-1640, Tyrode’s solution) with a decrease of sensitivity in comparison to standard PBS (pH7). The experiments in the microfluidic environment showed the sensitivity of the glucose sensor (40×100μm2) as ~14mA/M·cm2 for Tyrode’s solution. We utilized our glucose sensitive microelectrodes to measure the glucose concentration changes in 0.36nL volumes from single cardiac cells. The average glucose consumption rate was in the range of 0.14–0.22mM/min. The NanoPhysiometer is optically transparent, and allows the integration of fluorescence imaging techniques with electrochemical sensing in order to monitor complex dynamic cellular processes at the single cell level in a chemically controlled microenvironment.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the lab of Dr. Bjorn Knollmann for isolating the cardiac myocytes and helpful discussions. This work has been supported in part by NIH Grant U01AI061223 and the Vanderbilt Institute for Integrative Biosystems Research and Education.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baxter GT, Young ML, Miller DL, Owicki JC. Life Sciences. 1994;55:573–583. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00483-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CC, Pai CL, Chen WC, Jenekhe SA. Thin Solid Films. 2005;479:254–260. [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Jiang Y, Kan J. Biosens Bioelectron. 2006;22:639–643. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng C, Li M, Xie Q, Liu M, Yang Q, Xiang C, Yao S. Sens Actuators B. 2007;122:148–157. [Google Scholar]

- Eklund SE, Cliffel DE, Kozlov E, Prokop A, Wikswo J, Baudenbacher F. Anal Chim Acta. 2003;496:93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Eklund SE, Snider RM, Wikswo J, Baudenbacher F, Prokop A, Cliffel DE. J Electroanal Chem. 2006;587:333–339. [Google Scholar]

- Eklund SE, Taylor D, Kozlov E, Prokop A, Cliffel DE. Anal Chem. 2004;76:519–527. doi: 10.1021/ac034641z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ges IA, Baudenbacher F. J Experimental Nanosci. 2008;3:63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ges IA, Dzhura IA, Baudenbacher FJ. Biomedical Microdevices. 2008;10:347–354. doi: 10.1007/s10544-007-9142-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ges IA, Ivanov BL, Werdich AA, Baudenbacher FJ. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;22:1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CW, Lee GB. J Micromech Microengineering. 2007;17:1266–1274. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura J, Saito A, Ito N, Nakamoto S, Kuriyama T. J Membrane Science. 1989;43:291–305. [Google Scholar]

- Koudelka M, Gernet S, De Rooij NF. Sensors Actuators. 1989;18:157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre A, Olsina R, Raba J. Anal Chem. 1998;70:3679–3684. doi: 10.1021/ac9708194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao CW, Chou JC, Sun TP, Hsiung SK, Hsieh JH. Sensors Actuators B. 2007;123:720–726. [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima H, Ishino S, Masuda H, Nakagama T, Shimosaka T, Uchiyama K. Anal Chim Acta. 2006;562:103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ozoemena KI, Nyokong T. Electrochim Acta. 2006;51:5131–5136. [Google Scholar]

- Pasic A, Koehler H, Klimant I, Schaupp L. Sensors Actuators B. 2007;122:60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Salimi A, Sharifi E, Noorbakhsh A, Soltanian S. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;22:3146–3153. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan D, Zhu M, Xue H, Cosnier S. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;22:1612–1617. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldatkin AP, El’skaya AV, Shul’ga AA, Jdanova AS, Dzyadevich SV, Jaffrezic-Renault N, Clechet P. Anal Chim Acta. 1994;288:197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H. Electroanalysis. 2000;12:703–715. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Sato K, Shimizu T, Yamato M, Okano T, Kitamori T. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;23:449–458. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Updike SJ, Hicks GP. Nature. 1967;214:986. doi: 10.1038/214986a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XD, Zhou TY, Chen X, Wong KY, Wang XR. Sensors Actuators B. 2008;129:866–873. [Google Scholar]

- Werdich AA, Lima EA, Ivanov B, Ges I, Anderson ME, Wikswo JP, Baudenbacher FJ. Lab on Chip. 2004;4:357–362. doi: 10.1039/b315648f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West J, Becker M, Tombrink S, Manz A. Anal Chem. 2008;80:4403–4419. doi: 10.1021/ac800680j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu BY, Hou SH, Yin F, Zhao ZX, Wang YY, Wang XS, Chen Q. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;22:2854–2860. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, Zhang K, Bai Y, Yang W, Sun C. Bioelectrochem. 2006;69:158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao ZX, Qiao MQ, Yin F, Shao B, Wu BY, Wang XS, Qin X, Li S, Yu L, Chen Q. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;22:3021–3027. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]