Abstract

Purpose

RMFPNAPYL (RMF), a WT1-derived CD8 T cell epitope presented by HLA-A*02:01, is a validated target for T-cell-based immunotherapy. We previously reported ESK1, a high avidity (Kd < 0.2nM), fully-human monoclonal antibody (mAb) specific for the WT1 RMF peptide/HLA-A*02:01 complex, which selectively bound and killed WT1+ and HLA-A*02:01+ leukemia and solid tumor cell lines.

Experimental Design

We engineered a second-generation mAb, ESKM, to have enhanced antibody dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) function due to altered Fc glycosylation. ESKM was compared to native ESK1 in binding assays, in vitro ADCC assays, and mesothelioma and leukemia therapeutic models and pharmacokinetic studies in mice. ESKM toxicity was assessed in HLA-A*02:01+ transgenic mice.

Results

ESK antibodies mediated ADCC against hematopoietic and solid tumor cells at concentrations below 1µg/ml, but ESKM was about 5–10 fold more potent in vitro against multiple cancer cell lines. ESKM was more potent in vivo against JMN mesothelioma, and effective against SET2 AML and fresh ALL xenografts. ESKM had a shortened half-life (4.9 vs 6.5 days), but an identical biodistribution pattern in C57BL6/J mice. At therapeutic doses of ESKM, there was no difference in half-life or biodistribution in HLA-A*02:01+ transgenic mice compared to the parent strain. Importantly, therapeutic doses of ESKM in these mice caused no depletion of total WBCs or hematopoetic stem cells, or pathologic tissue damage.

Conclusions

The data provide proof of concept that an Fc-enhanced mAb can improve efficacy against a low-density, tumor-specific, peptide/MHC target, and support further development of this mAb against an important intracellular oncogenic protein.

INTRODUCTION

Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are highly specific and effective drugs, with pharmacokinetics suitable for infrequent dosing. However, all current marketed therapeutic anticancer mAbs target extracellular or cell-surface molecules, whereas many of the most important tumor-associated and oncogenic proteins are nuclear or cytoplasmic (1, 2). Intracellular proteins are processed by the proteasome and presented on the cell surface as small peptides in the pocket of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules HLA in humans) allowing recognition by T-cell receptors (TCRs) (3, 4). Therefore, mAbs that mimic the specificity of TCRs (that is, recognizing a peptide presented in the context of a specific HLA-type) can bind cell-surface complexes with specificity for an intracellular protein. A “TCR-mimic” (TCRm) antibody was first reported by Andersen et. al. (5), and several have since been developed by various groups (6–11).

We recently reported the first fully human TCRm mAb, called ESK1, that specifically targets RMFPNAPYL (RMF), a peptide derived from Wilms’ tumor gene 1 (WT1), presented in the context of HLA-A*02:01 (RMF/A2) (12). WT1 is an important, immunologically validated oncogenic target that has been the focus of many vaccine trials (13). WT1 is a zinc finger transcription factor with limited expression in normal adult tissues, but is over expressed in the majority of leukemias and a wide range of solid tumors, especially mesothelioma and ovarian cancer (14–16). WT1 was ranked as the top cancer antigenic target for immunotherapy by a National Institutes of Health-convened panel (17); further, WT1 expression is a biomarker and a prognostic indicator in leukemia (18, 19). ESK1 mAb specifically bound to leukemias and solid tumor cell lines that are both WT1+ and HLA-A*02:01+ and showed efficacy in mouse models in vivo against several WT1+ HLA-A*02:01+ leukemias (12). Therefore, ESK1 is a useful therapeutic platform for further clinical development, and improvements to the native antibody could help potentiate its effect and improve clinical efficacy.

The mechanisms of action of mAbs can be enhanced through Fc region protein engineering (20), or by modification of Fc-region glycosylation (21, 22). Removal of fucose from the carbohydrate chain increases mAb binding affinity for the activating FcγRIIIa receptor and enhances ADCC (23–26). The addition of bisecting N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (GlcNAc) can also significantly enhance ADCC (26–28). However, removal or replacement of the terminal galactose residues present on endogenous IgG reduces complement dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) activity (22, 29).

TCRm antibodies are potentially limited by the extremely low number of epitopes presented on the target cell, which may be as few as several hundred sites (30). Therefore, mechanisms to enhance potency may be essential to their success in humans as therapeutic agents against cancer. The ESK1 mAb works primarily through ADCC and therefore we hypothesized that an Fc-glycosylation altered version of the antibody would improve efficacy in vivo. An Fc-modified antibody was generated by expressing the ESK1 construct in MAGE 1.5 CHO cells (Eureka Therapeutics, Inc), resulting in a consistent pattern of defucosylation and exposed terminal hexose (mannose and/or glucose), allowing higher affinity for activating human FcγRIIIa and murine FcγRIV while decreasing affinity for inhibitory FcγRIIb. The modified antibody, “ESKM”, mediated ADCC at lower doses than native ESK1 and was more potent in human tumor models in vivo. Further, ESKM had similar pharmacokinetics and biodistribution to the native antibody. ESKM showed no observable off-target tissue sink in wild-type mice, and at therapeutic doses there was no difference in half-life or biodistribution in HLA-A2.1+ transgenic mice compared to the parent strain. Importantly, therapeutic doses of ESKM in these mice caused no depletion of total WBCs or hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), or pathologic tissue damage. The retained specificity, enhanced potency, favorable pharmacokinetics and distribution, and lack of toxicity in these models support ESKM as a promising lead clinical drug candidate to treat a wide variety of cancers and leukemias.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligosaccharide analysis and FcR binding assays

N-Glycan from ESK1 or ESKM was cleaved from antibody by PNGase F, and measured by HPAEC-PAD using PA200 column. Binding of ESK1/ESKM to mouse FcγR4 and mouse FcγRIIb were measured by ELISA. Briefly, 2µg/mL recombinant mouse FcγR4 or FcγRIIb were coated onto ELISA plate. Various concentrations of ESK1 or ESKM antibodies were added to the wells for 1 hour at room temperature, then detected by secondary antibody (HRP conjugated anti-human IgG Fab’2 fragment). Binding of ESK1/ESKM to human FcγRs was measured by Flow Cytometry (Guava easyCyte HT, Millipore) against CHO cells expressing appropriate human FcγR. Binding of ESK1/ESKM to human FcγRI, FcγRIIa, FcγRIIIa-158V, FcγRIIIa-158F and human FcRn were measured directly using ESK1 or ESK1 antibody, followed by the 2nd antibody (FITC conjugated Fab’2 fragment anti-human IgG Fab’2). For human FcγRIIb, dimers were formed first by mixing ESK1 or ESKM to a PE-conjugated Fab’2 fragment anti-human Fab’2 at 2:1 ratio at RT for 2 hour. Binding of dimeric complex of ESK1 or ESKM to human FcγRIIb were measured directly by Flow Cytometry using the immunocomplex.

Cells and reagents

Cell lines were from laboratory stocks, and were passaged in RPMI with 10% FBS for less than one month before experiments. Cell lines were from the same stocks as published previously (12), and were not tested and authenticated. An ovarian patient sample (WT1 positive by immunohistochemistry, and strongly positive for HLA-A2 and ESK mAb binding by flow cytometry) was obtained under MSKCC IRB approved protocols. For ALL leukemia animal studies, fresh pre-B cell ALL cells were obtained under MSKCC IRB approved protocols from the CNS relapse of a female pediatric patient after treatment with a chemotherapy induction regimen and bone-marrow transplant. Leukemia cells were transduced with a lentiviral vector containing a plasmid encoding luciferase/GFP (kindly provided by Vladimir Ponomarev, MSKCC). Luciferase+/GFP+ leukemia was then expanded in NSG mice, luciferase signal was confirmed by bioluminescent imaging, and tumor cells were harvested and sorted for CD45. Peptides for T2 pulsing assays were purchased and synthesized by Genemed Synthesis, Inc. Peptides were > 90% pure. GFP+ luciferase-expressing SET2 and JMN cells were generated as described previously (12). All cells were HLA typed by the Department of Cellular Immunology at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

Animals

C57BL/6 and C57BL/-Tg (HLA-A2.1) 1 Enge/J (6–8 week-old male), and NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ mice (6–8 week-old male), known as NOD scid gamma (NSG), were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Functionally equivalent NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Sug/JicTac (6–8 week-old male), known as NOG, and C.B-Igh-1b/IcrTac-Prkdcscid (6–8 week-old male), known as CB17 SCID, were purchased from Taconic. All studies were conducted in accordance with IACUC approved protocols.

Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC)

After informed consent on Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Institutional Review Board (MSKCC IRB) approved protocols, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors were obtained by Ficoll density centrifugation. Target cells used for ADCC were T2 cells pulsed with or without WT1 or RHAMM-3 peptides, and cancer cell lines or primary ovarian cancer sample without peptide pulsing. ESK1, ESKM or isotype control human IgG1 (Eureka Therapeutics, Inc) at various concentrations were incubated with target cells and fresh PBMCs at different effector: target (E:T) ratio. Cytotoxicity was measured by standard 4 hour 51Cr-release assay.

Therapy of ESK1 and ESKM in human mesothelioma, AML and ALL xenograft mouse models

Luciferase-expressing JMN cells (3×105) were injected into the intraperitoneal cavity of CB17 SCID mice. On day 4, tumor engraftment was confirmed by luciferase imaging, signal was quantified with Living Image software (Xenogen), and mice were sorted into groups with similar average signal from the supine position. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 50µg ESK1, ESKM or human isotype IgG1 antibody twice weekly beginning on day 4.

For AML leukemia studies, luciferase-expressing SET2 (AML) cells (3×106) were injected intravenously via tail vein into NSG mice. Animals were sorted, and, where indicated, treated with intraperitoneal injections of 100µg ESKM twice weekly beginning on day 6. For ALL studies, fresh leukemia cells were obtained as describe above (Cell lines and reagents) then injected intravenously into NSG mice (55×106/animal), and engraftment was confirmed by bioluminescent imaging on day 2 post-injection. Animals were sorted into two groups (n=5 each) so that average signal in each group was equal. ESKM or isotype control antibody (100µg/animal) was administered via retro-orbital injection on days 2, 5, 9, 12, 14 and 23, and leukemia growth was followed by bioluminescent imaging. On day 41, animals were sacrificed and bone marrow cells were harvested and pooled: after dissection and homogenization, cells were centrifuged, subjected to Ficoll density centrifugation, and counted after red blood cell lysis (acetic acid). An equal number of cells from each treatment group was resuspended in matrigel (200µL/injection) and engrafted subcutaneously into the opposite shoulders of NSG mice (n=4). No further treatment was given, and tumor growth was followed by bioluminescent imaging.

Pharmacokinetic and biodistribution studies

Antibody was labeled with 125I (PerkinElmer) using the chloramine-T method. 100µg antibody was reacted with 1mCi 125I and 20µg chloramine-T, quenched with 200µg Na metabisulfite, then separated from free 125I using a 10DG column equilibrated with 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS. Specific activities of products were in the range of 4–8 mCi/mg. Radiolabeled mAb was injected into mice retro-orbitally, and blood and/or organs were collected at various time points, weighed and measured on a gamma counter.

Toxicity studies

For isolated cell binding studies, C57BL6/J or HLA-A2.1+ transgenic mice were sacrificed, and cells were harvested from spleen, thymus and bone-marrow. After red blood cell lysis, cells (106 per tube, in duplicate) were incubated with 125I-labeled ESK1 (1 µg/ml) for 45 minutes on ice, then washed extensively with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS on ice. To determine specific binding, a set of cells was assayed after pre-incubation in the presence of 50-fold excess unlabeled ESK1 for 20 minutes on ice. Bound radioactivity was measured by a gamma counter, specific binding was determined, and the number of bound antibodies per cell was calculated from specific activity.

For toxicity studies, 100µg of ESKM or isotype control mAb was injected into human HLA-A*02:01 transgenic mice (Jackson Labs) on days 0 and 4, to mimic the maximum dose and therapeutic schedule used in the therapy experiments. Mice were sacrificed on day 5 for collection and analysis of whole blood and bone marrow leukocytes. Whole blood was analyzed with a Hemavet system (Drew Scientific). Bone marrow cells were harvested from both femurs and tibias of mice and subjected to red blood cell lysis, then analyzed by flow cytometry (see Antibodies and flow cytometry analysis).

Antibodies and flow cytometry analysis

For cell surface staining, cells were blocked with human FcR blocking reagent (Milteni Biotec), then incubated with appropriate mAbs for 30–60 minutes on ice. Flow cytometry data were collected on a FACS Calibur or LSRFortessa (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Treestar). APC-labeled ESK1 and hIgG1 isotype (Eureka Therapeutics, catalog number ET901) were generated with Lightning-Link® kit (Innova Biosciences). For human leukemia stem cell studies, cells were stained with the following antibodies, and corresponding fully-stained-minus-one controls: PE-Cy5 anti-human lineage cocktail (BioLegend; anti-CD3, CD14, CD16, CD19, CD20, CD56), FITC-labeled anti-CD38, PE-labeled anti-CD34, PE-Cy7-labeled BB7.2, and APC-labeled ESK1.

For HSC toxicity studies, mouse bone marrow cells were stained with the following antibodies: (Lineage; CD3, CD4, CD8, Gr1, B220, CD19, TER119, all conjugated with PE-Cy5), Sca-Pacific Blue, CD34-FITC, SLAM-APC, CD48-PE and c-KIT-AlexaFluor 780. The stained cells were analyzed for flow cytometry on the BD LSRII instrument.

For mouse immunophenotyping, cells were isolated from the intraperitoneal cavity by washing with complete media, or from spleen by dissection and red blood cell lysis (RBC Lysis Solution, Qiagen). Samples were then analyzed by flow cytometry after multi-color staining with well-characterized lineage-specific markers: CD335 (NKp46)-PE and F4/80 (BM8)-AlexaFluor700 (BioLegend), CD49b/VLA-2a (DX5)-FITC (Life Technologies), CD3e-PE-Cy7 and Gr-1/Ly-6G/Ly-6C (RB6-8C5)-PerCP-Cy5.5 (BD Pharmingen).

RESULTS

ESKM antibody has enhanced binding affinity for FcγRIIIa and reduced affinity for FcγRIIb

ESKM mAb was produced in MAGE 1.5 CHO cells, with the homogeneous oligosaccharide structure (Supplemental Fig. S1A) and no detectable fucose or galactose. ESKM had 80% higher affinity for activating human FcγRIIIa (158V variant), 3.5-fold higher affinity for the FcγRIIIa 158F variant, and 50% reduced affinity for inhibitory FcγRIIb. Importantly, ESKM affinity for FcRn was unchanged (Table 1 & Supplemental Fig. S1B). Similarly, ESKM had 51% higher affinity for activating mouse FcγRIV, and half the affinity for inactivating mouse FcγRIIb (Table 1 & Supplemental Fig. S1C). Changes in Fc glycosylation pattern did not affect antigen binding, as avidity of ESKM against WT1+ HLA-A*02:01+ JMN cells was nearly identical to the native ESK1 (0.2–0.4nM) (Table 1 & Supplemental Fig. S1D).

Table 1.

Summary of ESK1 and ESKM binding to mouse and human FcγRs, and RMF/A2+ target cells.

| Kd +/− SD (nM) | Ratio of Affinity Constants (ESKM/ESK1) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Receptor | ESK1 | ESKM | |

| Mouse | |||

| FcγRIIb | 32.0 +/− 0.454 | 62.3 +/− 7.27 | 0.51 |

| FcγRIV | 3.34 +/− 0.193 | 2.21 +/− 0.153 | 1.51 |

| Human | |||

| FcγRI | 0.581 +/− 0.113 | 0.680 +/− 0.125 | N.C. |

| FcγRIIa | 105 +/− 15.5 | 58.3 +/− 8.80 | 1.81 |

| FcγRIIb | 1338 +/− 253 | 2644 +/− 438 | 0.51 |

| FcγRIIIa (158V) | 92.6 +/− 15.0 | 50.4 +/− 8.35 | 1.84 |

| FcγRIIIa (158F) | 19.0 +/− 2.38 | 5.53 +/− 0.741 | 3.45 |

| FcRn | 824 +/− 102 | 780 +/− 97.5 | N.C. |

| Cell line | |||

| JMN | 0.2 | 0.4 | |

ADCC mediated by ESKM in vitro

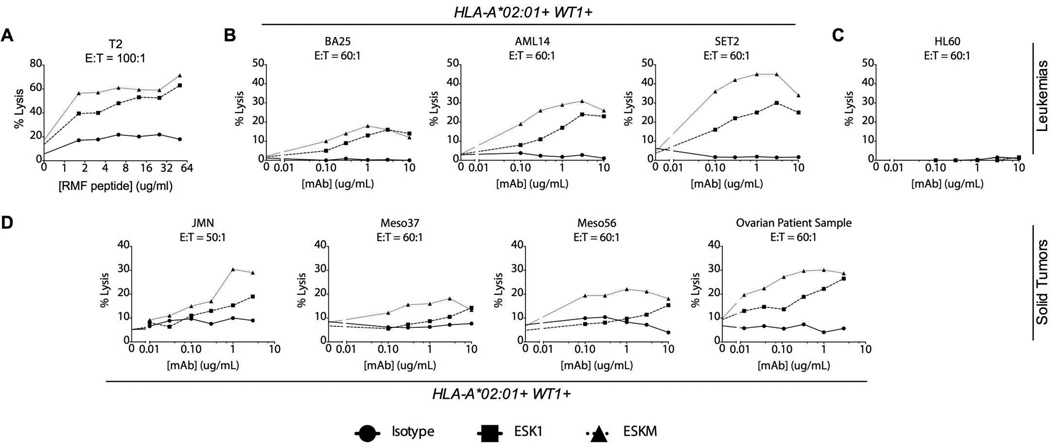

We investigated the relationship of cell surface antigen density with ESKM ADCC efficacy using T2, a TAP-deficient cell line that expresses HLA-A*02:01 but does not present peptides through the ER pathway, and thus can be loaded with exogenous peptides for presentation in a dose-dependent manner. To determine whether ESKM could better mediate ADCC against cells with low antigen density, we fixed the dose of ESK1 and ESKM mAbs and tested them against T2 cells loaded with titrated RMF peptide. Both antibodies were effective against T2 cells pulsed with high peptide concentrations, but ESKM was able to mediate greater ADCC against cells with fewer RMF/A2 complexes (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

ESKM is more efficacious and potent in ADCC assays with human PBMC effectors at the indicated mAb concentrations and effector/target (E:T) ratios. Cytotoxicity was measured by 4-hour 51Cr release assay. (A) T2 cells were pulsed with RMF peptide and incubated with 3µg/mL mAb. (B) HLA-A*02:01+ human leukemia cell lines: BA25 ALL, AML14 and SET2 AML (C) HLA-A*02:01 negative HL60 promyelocytic leukemia. (D) HLA-A*02:01+ human mesothelioma cell lines: JMN, Meso37 and Meso56; and a HLA-A*02:01+ primary human ovarian cancer. Data presented are averages of triplicate measurements, with spontaneous 51Cr release subtracted, from representative experiments, all with isolated PBMCs from the same donor. All cell lines, with exception of Meso37 and Meso56, were repeated 3 or more times with multiple donors.

We next determined the in vitro ADCC activity of ESK1 and ESKM against cell lines presenting a range of levels of cell surface RMF/A2 (12). ESKM showed both increased potency and efficacy against six leukemia and mesothelioma cell lines in an HLA-restricted manner. ESKM effectively mediated ADCC against BA-25, an acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cell line expressing approximately 1000–2000 RMF/A2 targets per cell; both antibodies were similarly effective at ADCC at concentrations above 1µg/mL, but ESKM was more potent at concentrations down to 100ng/ml of mAb (Fig 1B). Against AML-14 and SET2 acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cell lines, which both bind ~5000 mAb per cell, ESKM mediated higher cell lysis than ESK1 at the highest antibody concentrations, and showed cytolytic efficacy down to doses as low as 100ng/mL (Fig. 1B). As we have shown previously for ESK1 (12), ESKM did not kill leukemia cells not expressing HLA-A*02:01 (Fig 1C). Further, ESKM mediated higher specific lysis at nearly all doses tested against 3 HLA-A*02:01+ mesothelioma cell lines: JMN, Meso-37, and Meso-56 (Fig 1D). Importantly, ESKM was also more potent against a WT1+, HLA-A*02:01+ primary fresh patient ovarian cancer sample (Fig 1D), which was positive for ESK binding by flow cytometry. To assess the human effector cell populations responsible for ADCC in vitro, we separated whole blood from healthy donors into neutrophils and PBMCs, which were further sorted into macrophage/monocyte and NK cell populations (see Supplemental Methods). Only isolated NK cells were capable of ADCC directed by ESKM in vitro against BV173 target cells Supplemental Fig. S2). These data showed that ESKM was both more potent –as illustrated by its ability to kill cells with lower mAb concentrations and fewer cell surface targets—and more effective than ESK1, as demonstrated by higher specific lysis attained at the highest concentrations.

Potency of ESKM against human mesothelioma and leukemia models in mice

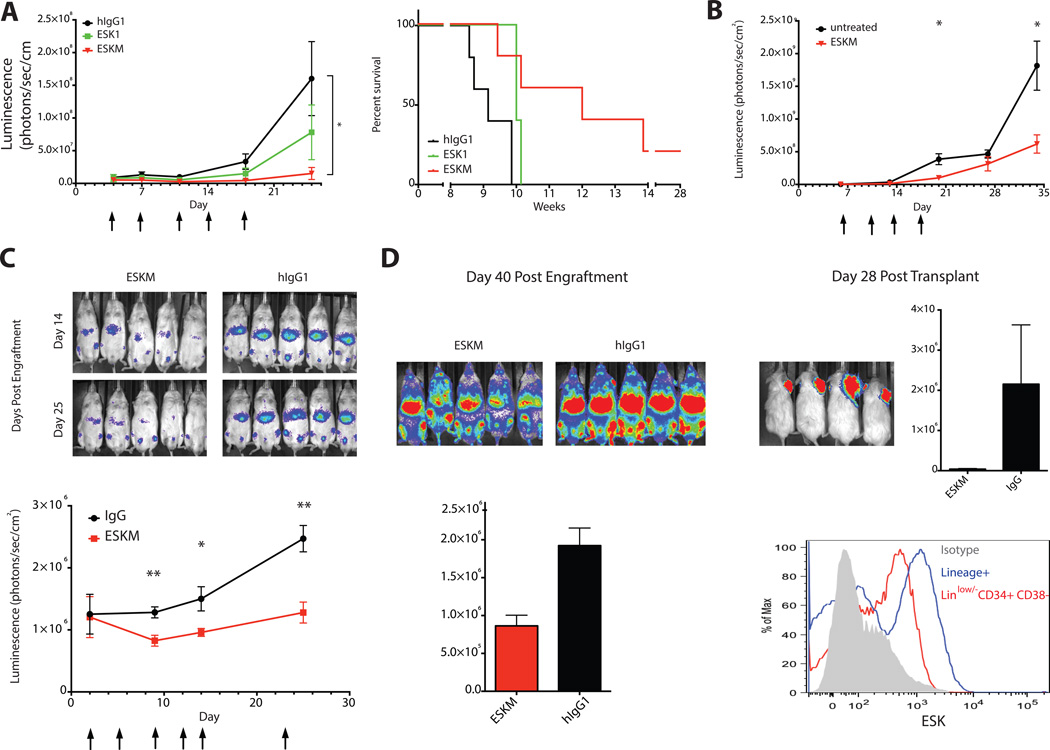

Data from several experiments in vitro and in vivo provided strong evidence that ADCC was the dominant mechanism of therapeutic action of the ESK1 mAb. (12). Here, we utilized a SCID mouse model to investigate whether ESKM offered a consistent and significant improvement over native ESK1 in vivo in mice with more available effector cells capable of ADCC than NSG/NOG mice (12). ESKM more effectively engages activating murine FcγRIIa and FcγRIV, therefore murine cells should serve as potent effectors in vivo. Mice were engrafted with luciferase+ JMN mesothelioma cells in the intraperitoneal cavity (simulating this serosal cavity cancer). To determine the relative abundance of murine effector cell populations in the intraperitoneal cavity, we analyzed extracted cells with common murine immunophenotyping markers (31). SCID mice contain intraperitoneal macrophages, neutrophils and NK-cells (Table 2). This flow cytometry analysis also confirmed the presence of murine monocytes, macrophages and NK cells, but lack of B- and T-cells in the spleen and peripheral blood, as expected (32). Biweekly 50µg treatment with ESKM was more effective than ESK1 against intraperitoneal JMN, and significantly improved survival over isotype control antibody (Fig. 2A). Further, ESKM was able to reduce tumor burden during the treatment course, whereas ESK1 merely slowed growth (Supplementary Fig. S3A). In a third experiment at the same dose and schedule, neither antibody construct showed efficacy against intraperitoneal JMN in NOG mice (Supplemental Fig. S3B), which lack NK-cells and intraperitoneal neutrophils (Table 2), indicating that these cell populations likely play an important role in efficacy in the intraperitoneal model.

Table 2.

Intraperitoneal effector cell populations in BALB/c, SCID, and NOG mice.

| Cells (% of parent population) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Population |

Cell type | Marker Phenotype |

BALB/c | CB17 SCID | NOG |

| CD11b+ | |||||

| Granulocyte | Gr-1+ F4/80− | 46.6 +/− 28.3 | 7.45 +/− 2.71 | 0.215 +/− 0.137 | |

| Macrophage | Gr-1low F4/80+ | 10.5 +/− 6.87 | 19.0 +/− 1.29 | 96.3 +/− 1.06 | |

| Monocyte | Gr-1− F4/80− | 39.2 +/− 21.1 | 70.2 +/− 2.73 | 1.25 +/− 0.562 | |

| CD11b− | |||||

| NK cell | NKp46+ CD3e− | 1.68 +/− 0.250 | 36.2 +/− 12.0 | 0.278 +/− 0.413 | |

Figure 2.

ESKM is superior to ESK1 in vivo, and is effective against multiple tumor models. Tumor burden was determined by luciferase imaging of mice in the supine position (n=5 per group). Data points are averages of each group, and error bars represent SEM. Arrows indicate treatment with mAb. (A) ESKM significantly reduced mean tumor growth of intraperitoneal JMN mesothelioma as assessed by total luminescence (*p<0.05, multiple T-tests on and after day 18), and also significantly improved survival (p=0.016 vs isotype, p=0.095 vs ESK1), with events representing death or terminal morbidity as assessed on protocol by veterinarians. (B) ESKM is effective against SET2 AML (*p<0.05, multiple T-tests). (C) ESKM is effective against a disseminated fresh, patient-derived pre-B ALL (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, multiple T-tests). (D) Leukemia burden in the bone marrow was quantitated by imaging on day 40, then bone marrow cells were harvested from mice in C and transplanted as subcutaneous tumors into NSG mice. Bone marrow cells from the isotype-treated mice were injected into the right shoulder (viewed from above), while an equal number of bone marrow cells from the ESKM-treated mice were injected into the left shoulder. Subcutaneous tumors were then quantitated 28 days post transplantation. In a multi-color flow cytometry analysis of a frozen stock of the same fresh primary ALL sample (before passage in animals), ESK mAb bound the lineagelow/− CD34+ CD38− subset.

We previously reported that ESKM is effective at a low dose against disseminated bcr/abl+ BV173 ALL in a NSG mouse model, where FcγRIV+ monomyeloid cells are present in the spleen (33). We therefore used NSG mice to evaluate ESKM efficacy against disseminated leukemia models. We first investigated ESKM against SET2, an AML that grew more aggressively than BV173 in the NSG mouse model (Supplemental Fig. S3C). ESKM significantly reduced tumor growth (Fig. 2B). ESKM also significantly reduced initial burden and slowed outgrowth of a patient-derived human pre-B-cell ALL (Fig. 2C). Leukemia relapsed after treatment was stopped, allowing us to collect leukemia cells from the bone marrow and transplant to new animals to assess outgrowth from remaining progenitors. Total bone marrow signal in ESKM-treated mice was lower at time of transplant, but equal numbers of ESKM-treated and isotype-treated bone marrow cells were engrafted into recipient animals. Subcutaneous leukemia tumors from isotype-treated leukemia cells grew to 50 times the total signal compared to tumors from ESKM-treated cells (Fig. 2D). In this same patient ALL sample, ESK bound a lineagelow, CD34+, CD38− population, characterized as a cancer stem cell population in ALL (34), at nearly the same level as lineage+ populations (Figure 2D and Supplemental Methods). This suggests that ESKM therapy could target this population, but does not imply that ESK mAbs can differentiate between leukemic stem cell and normal HSC populations. Further supporting the hypothesis that ESK mAbs can target leukemic progenitor cells, ESK1 bound CD33+/CD34+ cells from a separate HLA-A*02:01+ AML patient with ~8-fold shift in median fluorescence intensity of ESK1 compared to isotype control antibody (12).

Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of ESK1 and ESKM

Altering Fc glycosylation could potentially change pharmacokinetic properties of the mAb, thereby affecting its therapeutic utility. Trace 125I-labeled antibodies were injected intravenously into C57 BL6/J mice and blood levels of mAb were measured over 7 days. Both ESK1 and ESKM exhibited biphasic clearance, with initial tissue distribution and an alpha half-life of 1.1 – 2.4hr, followed by a slower beta half-life of several days (Fig. 3A). ESKM had a shorter beta half-life than ESK1 (4.9 days vs 6.5 days). The biodistribution patterns of the antibodies were determined using the same radiolabeled constructs. Both antibodies displayed similar patterns of organ distribution and clearance (Fig. 3A). While increased FcγR binding or manose receptor binding could create a sink for ESKM, we found no increase in ESKM distribution to the liver, spleen, thymus or bone marrow that could account for the shortened serum half-life.

Figure 3.

ESKM and native ESK1 display similar pharmacokinetics and biodistribution. 125I-labeled mAb was injected IV and activity was measured in blood or harvested organs (n=3 per group). Data points are averages of each group, and error bars represent SEM. (A) Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of ESKM or native ESK1 (3µg each) in C57BL6/J mice. (B) Pharmacokinetics of trace ESKM (2µg) and 24-hour biodistribution of ESKM (100µg) in C57BL6/J or HLA-A*02:01+ transgenic mice. (C-D) ESKM (C) or hIgG1 isotype control (D) (2µg each) in C57BL6/J or HLA-A*02:01+ transgenic mice, harvested after 1 day.

As the ESKM antibody targets a human-specific epitope, the C57BL6/J mouse model cannot recapitulate possible on-target binding to normal tissues that could alter antibody pharmacokinetics and biodistribution. Therefore, we used a transgenic mouse model based on the C57BL6/J background that expresses human HLA-A*02:01 driven by a lymphoid promoter. We confirmed the presence of surface HLA-A*02:01 on murine cells by flow cytometry with the BB7.2 antibody. Leukocytes isolated from thymus tissue showed low but detectable binding, while cells isolated from the bone marrow and spleen showed appreciable binding, with a 5 to 10-fold shift in median fluorescent intensity over isotype control antibody, comparable to surface HLA-A*02:01 levels observed on human PBMCs from healthy donors (12). The 9-mer RMF sequence is identical in human and mouse, and therefore this transgenic model could recapitulate antigen presentation of the RMF/A2 epitope in healthy cells. There was no difference between wild-type and HLA-A*02:01 transgenic mice in blood pharmacokinetics of ESKM, indicating that there was no significant antibody sink. Further, at a therapeutic dose of antibody (100µg), there was no difference in biodistribution in transgenic compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 3B).

At low doses of trace-labeled ESKM (2µg) there was a small yet detectable increase in uptake of antibody in the spleen of transgenic mice compared to wild-type (Fig. 3C). The additional splenic binding was small, accounting for only 16ng of antibody, which could be due to RMF presentation in HLA-A*02:01+ cells, or to an unknown cross-reacting epitope. Splenic uptake was not due to Fc glycosylation pattern alone, as the native ESK1 mAb also showed increased uptake in transgenic spleens at 24 hours (Supplemental Fig. S4A). Additionally, increased spleen uptake in transgenic mice appeared to be partly related to strain differences in clearance, as the isotype control antibody also showed 60% increased splenic uptake at 24 hours in transgenic compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 3D and Supplemental Fig. S4A). Further, we observed no binding of ESK1 to cells isolated from transgenic mouse spleen cells by either flow cytometry (12) or specific binding assay with 125 I-labeled ESK1 (Supplemental Fig. S4B), suggesting that if a cross-reacting epitope was present, it was not expressed in detectable amounts on a specific cell type.

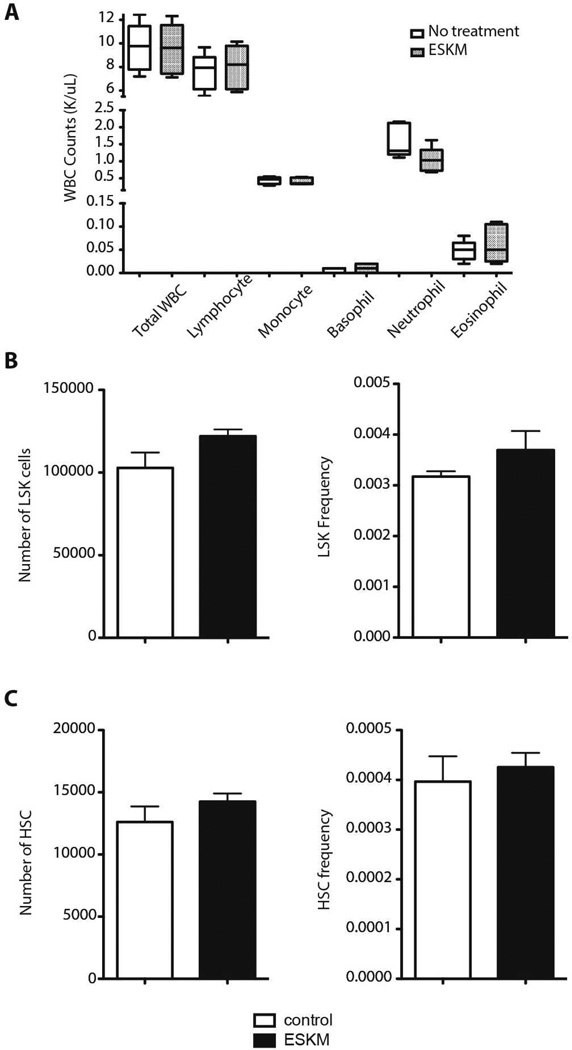

Toxicity of ESKM in a HLA-A*02:01 transgenic mouse model

WT1 is reported to be expressed in hematopoetic stem cells (HSC)(35), so the C57 BL6/J transgenic mouse model with human HLA-A*02:01 driven by a lymphoid promoter provides an opportunity to assess possible toxicity against progenitor cells in the hematopoetic compartment that, given the high potency of ESKM, might occur even at low epitope density. White blood cell and bone-marrow cell counts were assessed one day after the final of two therapeutic doses of ESKM or isotype control mAb on the same schedule as previously described therapy experiments (12). There were no differences in total white blood cell count, or lymphocyte, neutrophil, monocyte, eosinophil or basophil cell counts (Fig. 4A). Within the bone-marrow compartment, we found equivalent absolute number and frequency of hematopoetic stem cell (HSC) progenitors (LSK: Lineagelo, c-kit+, Sca1+) (Fig. 4B) and HSCs (CD150hi, CD48−, LSK) (Fig. 4C) in the ESKM treated and isotype control-treated mice.

Figure 4.

ESKM treatment does not affect leukocyte or hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) counts in HLA-A*02:01+ transgenic mice. Animals (n=5 per group) were treated with 100µg ESKM or hIgG1 isotype control on days 0 and 4; blood and bone marrow were harvested on day 5. Data points are averages of each group, and error bars represent SEM. (A) Total white blood cell (WBC) and WBC subset cell counts. (B) Absolute number and frequency of lineage− SCA1+ KIT+ (LSK) cells. (C) Absolute number and frequency of long-term HSCs (Slamf1+ CD34− LSK cells).

Finally, we assessed gross and microscopic pathology of lymphoid and major organs of HLA-A*02:01 transgenic mice treated with ESKM or isotype mAb on the same schedule. No striking differences between ESKM- and isotype-treated groups were observed by a trained hematopathologist (Supplemental Table S1). The bone marrow sections of both groups showed trilineage hematopoiesis with adequate maturation of the myeloid and erythroid lineages. The megakaryocytes were adequate in number with normal morphology. Thymus sections showed a well-defined cortex and medulla with few Hassall’s corpuscles, which is normal for rodent histology (36). The kidney sections showed no pathologic findings such as glomerulosclerosis, congestion, or inflammation. All spleen sections showed a normal distribution of red and white pulp. Occasional scattered megakaryocytes were seen in the red pulp consistent with extramedullary hematopoiesis (37).

DISCUSSION

The generation of TCRm antibodies allows use of the mAb to target cell-surface fragments of intracellular proteins, provided that they are processed and presented on MHC class I molecules. ESK1 was the first TCRm antibody reported against a peptide derived from WT1, an important oncogene expressed in a wide variety of cancers, but not normal adult tissues. WT1 appears to be expressed in leukemic stem cells (35), raising the possibility that the mAb could ultimately eliminate clonogenic leukemia cells in patients. Other therapeutic TCRm mouse antibodies, human ScFv and Fab fragments have been previously described (6–8, 10, 11). However, ESK1 is the first and only fully human therapeutic TCRm mAb reported. Features of the RMF/A2 epitope, especially the low levels of expression on the cell surface, require selection of a highly potent and effective ESK1 construct. We chose to improve the ESK1 construct by altering Fc glycosylation as a means to enhance ADCC, the major mechanism of ESK1 action in vitro and in vivo (12). Several ADCC-enhanced mAbs to highly expressed cell-surface antigens, produced, either by glyco-engineering or point mutations, are in clinical trials in the U.S. with promising results (38–40). The ESKM mAb had a homogeneous glycosylation pattern lacking N-linked fucose and with terminal hexose (mannose and/or glucose) structure. This engineering strategy modulates mAb binding to Fcγ receptors in two ways: a higher affinity for activating human FcγRIIIa (and murine FcγRIV) increases ADCC activity; while diminished affinity for both human and murine FcγRIIb should reduce inhibitory receptor activation. As expected, ESKM was both more potent and effective in vitro even at very low epitope density.

ESKM was also more effective than ESK1 in vivo, and was able to treat peritoneal mesothelioma in SCID mice, modeling the clinical situation. Further, ESKM significantly slowed leukemia growth of disseminated SET2, an AML cell line with much more aggressive in vivo leukemia growth kinetics than BV173, and a fresh patient-derived pre-B-cell ALL in xenograft models. In the fresh ALL model, tumor relapsed after mAb therapy was stopped, but leukemia cells extracted from the bone marrow of ESKM-treated mice and transplanted as subcutaneous tumors showed minimal outgrowth. This suggests that ESKM may target a progenitor population of leukemia cells. This supposition is supported by binding of ESK to a lineagelow/−, CD34+, CD38− population by flow cytometry, and consistent with the hypothesis that WT1 expression in HSCs could allow reduction of this population. However, cells collected from the bone marrow after relapse were not phenotyped and sorted, so we cannot determine the exact cell population targeted. ESKM was not curative in the models tested, possibly because of the lack of NK cells in NOG/NSG mice and short treatment courses. In this system, an incomplete effect is not surprising, and may not accurately model the effect in humans.

ESKM therapy was not effective against peritoneal mesothelioma in NSG or NOG mice, which lack NK-cells and neutrophils, though naked ESK1 did previously show potent activity against a disseminated leukemia model in these mice. This discrepancy could be due both to the tumor model—leukemia cells could have different sensitivity to effector-mediated cytotoxicity—and to the availability of intraperitoneal effector cells in the NSG/NOG model: our assays indicated that the intraperitoneal cavity of NOG mice contained predominately macrophages, while neutrophils were present in the blood and spleen, as previously reported (33). The marked improvement in efficacy with the Fc-enhanced mAb in SCID mice indicated that NK cells and/or monocytes (both with FcγRIV) are important to therapy in the intraperitoneal mesothelioma model, while splenic and circulating neutrophils presumably mediate ADCC against disseminated leukemias in NSG/NOG mice.

Altering Fc glycosylation could potentially change pharmacokinetic properties of the mAb through a number of mechanisms, including: altered FcRn binding and antibody recycling, modified binding to circulating effector cells, and differential engagement with clearance mechanisms, such as mannose receptors. Similar afucosylated, Fc-modified antibodies with improved ADCC have been investigated in pharmacokinetic studies in vivo (41, 42). ESKM had nearly identical biodistribution to ESK1, but a shortened blood half-life. We saw no change in biodistribution pattern that could account for this altered half-life. IgG half-life is regulated by the neonatal Fc receptor, FcRn (43, 44); however, ESKM had identical affinity for FcRn as ESK1. The altered pharmacokinetics is possibly due to interaction with mannose receptor on macrophages, a known mechanism of glycoprotein clearance (45–47). ESK1 and ESKM half-lives could be quite different in humans—where higher affinity binding to Fc receptors and clearance through human mannose receptors could have a role—as seen with other high-mannose IgG antibodies in humans (48).

Since ESK mAbs target a human HLA-specific epitope, we utilized the human HLA-A*02:01+ transgenic mouse strain for toxicology studies. WT1 is reportedly expressed in HSCs, yet a therapeutic dose of ESKM that cleared leukemia in our models had no effect on LSK cells or early HSCs. Importantly, ESKM did not affect the architecture or cell coverage in the bone marrow, thymus or spleen, where WT1+ HSCs could be expected, and where HLA-A*02:01 expression is highest because the transgene is driven by a lymphoid promoter. This transgenic system is the best available for predicting potential off target toxicity, but is limited to hematopoietic tissues. Despite this limitation, the lack of ESKM toxicity against those tissues shown to express human HLA-A*02:01 suggests that ESKM may be well tolerated in humans.

Selection of ESKM as a lead construct for human clinical development required us to consider its features of a moderately decreased half-life yet increased potency and broader applicability. The potential enhanced efficacy against tumors expressing fewer RMF/A2 sites could expand the number of patients and cancer types eligible for this therapy as well as increase efficacy. In addition, the MAGE 1.5 CHO engineering technology generates mAbs that effectively engage FcγRIIIa (CD16), regardless of amino acid 158 polymorphism. Carriers of CD16–158F are less responsive than CD16–158V/V individuals to human IgG1 therapeutics such as rituximab and trastuzumab (49, 50). WT1 is expressed in multiple cancers (14), making RMF/A2 a potential therapeutic target for many indications. Despite this potentially broad base of cancers, ESKM and most TCRm antibodies developed to date are directed to peptides presented by HLA-A*02:01, as this is the most common allele in the US population. Patients with other epitopes thus will not benefit from ESKM and additional analogous TCRm mAbs would be necessary for these patients. Further, ESKM binding depends on the level of HLA-A*02:01 expression, and on WT1 processing and peptide presentation on the cell surface. These processes could be aberrant in cancer cells. In preclinical models, we have shown efficacy against bcr/abl+ ALL and B-ALL (12), and here, AML, mesothelioma and primary ALL xenografts. In summary, ESKM is a potent therapeutic mAb against a widely expressed oncogenic target with a restricted normal cell expression profile, and has shown efficacy against multiple human tumor models in mice.

Supplementary Material

STATEMENT OF TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

Wilms’ tumor protein (WT1) is an intracellular, oncogenic transcription factor that is over-expressed in a wide range of cancers, but has limited expression in normal adult tissues. ESK1, a human IgG1 mAb, mimics T-cell receptor specificity for a WT1-derived peptide (RMF) presented by HLA-A*02:01 and kills cancer cells via antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), suggesting that it could treat a wide range of cancers while sparing normal tissue. However, RMF/ HLA-A*02:01 epitope levels are far lower than other therapeutic mAb targets, so enhanced ADCC activity should be more valuable clinically. ESKM, a construct with altered Fc glycosylation, demonstrated increased ADCC activity in vitro and greater potency and efficacy in mice. ESKM was not toxic to human HLA-A*02:01 transgenic mice. This study provides proof of concept that an ADCC-enhanced mAb construct can effectively treat cancers while targeting a low-density peptide/HLA epitope (500–6,000 per cell), and supports the clinical utility of ESKM.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Elliott Brea and Andrew Scott for helpful discussions.

FUNDING

Supported by the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, NIH R01CA55349 and P01 23766, and T32 CA062948 (N.V.), and the Major Family Fund.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST:

HL, JX, and CL: Employees of Eureka Therapeutics, Inc, which holds intellectual property protection around ESK antibodies and generation. NV, TD, LD and DAS: patents pending related to ESK antibodies. All others: No conflicts to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sensi M, Anichini A. Unique tumor antigens: evidence for immune control of genome integrity and immunogenic targets for T cell-mediated patient-specific immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5023–5032. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler JH, Melief CJ. Identification of T-cell epitopes for cancer immunotherapy. Leukemia. 2007;21:1859–1874. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris E, Hart D, Gao LQ, Tsallios A, Xue SA, Stauss H. Generation of tumor-specific T-cell therapies. Blood Reviews. 2006;20:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konig R. Interactions between MHC molecules and co-receptors of the TCR. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2002;14:75–83. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(01)00300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersen PS, Stryhn A, Hansen BE, Fugger L, Engberg J, Buus S. A recombinant antibody with the antigen-specific, major histocompatibility complex-restricted specificity of T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:1820–1824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epel M, Carmi I, Soueid-Baumgarten S, Oh SK, Bera T, Pastan I, et al. Targeting TARP, a novel breast and prostate tumor-associated antigen, with T cell receptor-like human recombinant antibodies. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1706–1720. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wittman VP, Woodburn D, Nguyen T, Neethling FA, Wright S, Weidanz JA. Antibody targeting to a class I MHC-peptide epitope promotes tumor cell death. J Immunol. 2006;177:4187–4195. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.4187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klechevsky E, Gallegos M, Denkberg G, Palucka K, Banchereau J, Cohen C, et al. Antitumor activity of immunotoxins with T-cell receptor-like specificity against human melanoma xenografts. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6360–6367. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhattacharya R, Xu Y, Rahman MA, Couraud PO, Romero IA, Weksler BB, et al. A novel vascular targeting strategy for brain-derived endothelial cells using a TCR mimic antibody. J Cell Physiol. 2010;225:664–672. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verma B, Neethling FA, Caseltine S, Fabrizio G, Largo S, Duty JA, et al. TCR mimic monoclonal antibody targets a specific peptide/HLA class I complex and significantly impedes tumor growth in vivo using breast cancer models. J Immunol. 2010;184:2156–2165. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sergeeva A, Alatrash G, He H, Ruisaard K, Lu S, Wygant J, et al. An anti-PR1/HLA-A2 T-cell receptor-like antibody mediates complement-dependent cytotoxicity against acute myeloid leukemia progenitor cells. Blood. 2011;117:4262–4272. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-299248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dao T, Yan S, Veomett N, Pankov D, Zhou L, Korontsvit T, et al. Targeting the Intracellular WT1 Oncogene Product with a Therapeutic Human Antibody. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:176ra33. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dao T, Scheinberg DA. Peptide vaccines for myeloid leukaemias. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2008;21:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka-Harada Y, Kawakami M, Oka Y, Tsuboi A, Katagiri T, Elisseeva OA, et al. Biased usage of BV gene families of T-cell receptors of WT1 (Wilms' tumor gene)-specific CD8+ T cells in patients with myeloid malignancies. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:594–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01453.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soslow RA. Histologic subtypes of ovarian carcinoma: an overview. International journal of gynecological pathology : official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists. 2008;27:161–174. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e31815ea812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raja S, Murthy SC, Mason DP. Malignant pleural mesothelioma. Current oncology reports. 2011;13:259–264. doi: 10.1007/s11912-011-0177-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheever MA, Allison JP, Ferris AS, Finn OJ, Hastings BM, Hecht TT, et al. The prioritization of cancer antigens: a national cancer institute pilot project for the acceleration of translational research. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5323–5337. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue K, Sugiyama H, Ogawa H, Nakagawa M, Yamagami T, Miwa H, et al. WT1 as a new prognostic factor and a new marker for the detection of minimal residual disease in acute leukemia. Blood. 1994;84:3071–3079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogawa H, Tamaki H, Ikegame K, Soma T, Kawakami M, Tsuboi A, et al. The usefulness of monitoring WT1 gene transcripts for the prediction and management of relapse following allogeneic stem cell transplantation in acute type leukemia. Blood. 2003;101:1698–1704. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desjarlais JR, Lazar GA, Zhukovsky EA, Chu SY. Optimizing engagement of the immune system by anti-tumor antibodies: an engineer's perspective. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12:898–910. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jefferis R. Glycosylation of recombinant antibody therapeutics. Biotechnol Prog. 2005;21:11–16. doi: 10.1021/bp040016j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodoniczky J, Zheng YZ, James DC. Control of recombinant monoclonal antibody effector functions by Fc N-glycan remodeling in vitro. Biotechnol Prog. 2005;21:1644–1652. doi: 10.1021/bp050228w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Romeuf C, Dutertre CA, Le Garff-Tavernier M, Fournier N, Gaucher C, Glacet A, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia cells are efficiently killed by an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody selected for improved engagement of FcgammaRIIIA/CD16. Br J Haematol. 2008;140:635–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masuda K, Kubota T, Kaneko E, Iida S, Wakitani M, Kobayashi-Natsume Y, et al. Enhanced binding affinity for FcgammaRIIIa of fucose-negative antibody is sufficient to induce maximal antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:3122–3131. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shields RL, Lai J, Keck R, O'Connell LY, Hong K, Meng YG, et al. Lack of fucose on human IgG1 N-linked oligosaccharide improves binding to human Fcgamma RIII and antibody-dependent cellular toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26733–26740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shinkawa T, Nakamura K, Yamane N, Shoji-Hosaka E, Kanda Y, Sakurada M, et al. The absence of fucose but not the presence of galactose or bisecting N-acetylglucosamine of human IgG1 complex-type oligosaccharides shows the critical role of enhancing antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3466–3473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210665200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davies J, Jiang L, Pan LZ, LaBarre MJ, Anderson D, Reff M. Expression of GnTIII in a recombinant anti-CD20 CHO production cell line: Expression of antibodies with altered glycoforms leads to an increase in ADCC through higher affinity for FC gamma RIII. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2001;74:288–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Umana P, Jean-Mairet J, Moudry R, Amstutz H, Bailey JE. Engineered glycoforms of an antineuroblastoma IgG1 with optimized antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxic activity. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:176–180. doi: 10.1038/6179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boyd PN, Lines AC, Patel AK. The effect of the removal of sialic acid, galactose and total carbohydrate on the functional activity of Campath-1H. Mol Immunol. 1995;32:1311–1318. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(95)00118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Veomett N, Dao T, Scheinberg DA. Therapeutic antibodies to intracellular targets in cancer therapy. Expert opinion on biological therapy. 2013;13:1485–1488. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2013.833602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai L, Alaverdi N, Maltais L, Morse HC., 3rd Mouse cell surface antigens: nomenclature and immunophenotyping. J Immunol. 1998;160:3861–3868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bosma MJ, Carroll AM. The SCID mouse mutant: definition, characterization, and potential uses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:323–350. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shultz LD, Lyons BL, Burzenski LM, Gott B, Chen X, Chaleff S, et al. Human lymphoid and myeloid cell development in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2R gamma null mice engrafted with mobilized human hemopoietic stem cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:6477–6489. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cox CV, Evely RS, Oakhill A, Pamphilon DH, Goulden NJ, Blair A. Characterization of acute lymphoblastic leukemia progenitor cells. Blood. 2004;104:2919–2925. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ariyaratana S, Loeb DM. The role of the Wilms tumour gene (WT1) in normal and malignant haematopoiesis. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2007;9:1–17. doi: 10.1017/S1462399407000336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Center TUoTMDAC. Atlas of Laboratory Mouse Histology. [cited June 13, 2012]; Available from: http://ctrgenpath.net/static/atlas/mousehistology/Windows/introduction.html. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cesta MF. Normal structure, function, and histology of the spleen. Toxicol Pathol. 2006;34:455–465. doi: 10.1080/01926230600867743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kubota T, Niwa R, Satoh M, Akinaga S, Shitara K, Hanai N. Engineered therapeutic antibodies with improved effector functions. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1566–1572. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ishida T, Joh T, Uike N, Yamamoto K, Utsunomiya A, Yoshida S, et al. Defucosylated anti-CCR4 monoclonal antibody (KW-0761) for relapsed adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma: a multicenter phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:837–842. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subramaniam JM, Whiteside G, McKeage K, Croxtall JC. Mogamulizumab: first global approval. Drugs. 2012;72:1293–1298. doi: 10.2165/11631090-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gasdaska JR, Sherwood S, Regan JT, Dickey LF. An afucosylated anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody with greater antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and B-cell depletion and lower complement-dependent cytotoxicity than rituximab. Mol Immunol. 2012;50:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Junttila TT, Parsons K, Olsson C, Lu Y, Xin Y, Theriault J, et al. Superior in vivo efficacy of afucosylated trastuzumab in the treatment of HER2-amplified breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4481–4489. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raghavan M, Bjorkman PJ. Fc receptors and their interactions with immunoglobulins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:181–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roopenian DC, Akilesh S. FcRn: the neonatal Fc receptor comes of age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:715–725. doi: 10.1038/nri2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allavena P, Chieppa M, Monti P, Piemonti L. From pattern recognition receptor to regulator of homeostasis: the double-faced macrophage mannose receptor. Crit Rev Immunol. 2004;24:179–192. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v24.i3.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee SJ, Evers S, Roeder D, Parlow AF, Risteli J, Risteli L, et al. Mannose receptor-mediated regulation of serum glycoprotein homeostasis. Science. 2002;295:1898–1901. doi: 10.1126/science.1069540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stahl PD. The mannose receptor and other macrophage lectins. Current Opinion in Immunology. 1992;4:49–52. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(92)90123-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goetze AM, Liu YD, Zhang Z, Shah B, Lee E, Bondarenko PV, et al. High-mannose glycans on the Fc region of therapeutic IgG antibodies increase serum clearance in humans. Glycobiology. 2011;21:949–959. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cartron G, Dacheux L, Salles G, Solal-Celigny P, Bardos P, Colombat P, et al. Therapeutic activity of humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and polymorphism in IgG Fc receptor FcgammaRIIIa gene. Blood. 2002;99:754–758. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Musolino A, Naldi N, Bortesi B, Pezzuolo D, Capelletti M, Missale G, et al. Immunoglobulin G fragment C receptor polymorphisms and clinical efficacy of trastuzumab-based therapy in patients with HER-2/neu-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1789–1796. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.