Abstract

Background

The Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) was a 7-year randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the efficacy of finasteride for the prevention of prostate cancer with a primary outcome of histologically-determined prevalence of prostate cancer at the end of 7 years.

Methods

A systematic modeling process using logistic regression identified factors available at year 6 that are associated with end-of-study (EOS) biopsy adherence at year 7, stratified by whether participants were ever prompted for a prostate biopsy by year 6. Final models were evaluated for discrimination. At year 6, 13,590 men were available for analysis.

Results

Participants were more likely to have the EOS biopsy if they were adherent to study visit schedules and procedures and/or were in good health (p<.01). Participants at larger sites and/or sites that received retention and adherence grants were also more likely to have the EOS biopsy (p<.05).

Conclusions

Our results show good adherence to study requirements one year prior to the EOS biopsy was associated with greater odds that a participant would comply with the invasive EOS requirement.

Impact

Monitoring adherence behaviors may identify participants at risk of non-adherence to more demanding study end points. Such information could help frame adherence intervention strategies in future trials.

Keywords: end-of-study biopsy, Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial, medical procedure adherence, invasive procedure

Introduction

Medical professionals and researchers recognize that non-adherence to medical treatment remains a challenge and have devoted significant resources to the development of intervention strategies to improve adherence rates. Despite these efforts, half of the strategies that are developed and tested fail [2]. The preponderance of the literature is devoted to medication adherence, particularly in patients with chronic illnesses, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or HIV, but there is a small literature examining adherence to clinical procedures.

End-of-study (EOS) Biopsy

The Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) was unusual in that its primary outcome (prevalence of prostate cancer during the seven-year trial) was based on a non-clinically indicated biopsy at the end of the trial. [3] A few studies have addressed adherence to a prostate biopsy recommendation and factors associated with agreeing to have the procedure. The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO) offers an opportunity to examine adherence to prostate biopsy screening recommendations. In this trial, across cancer disease sites, adherent participants were younger, had higher levels of education, and did not have a first-degree relative with cancer [4]. Pinsky et al. examined factors associated with undergoing a prostate biopsy after a positive PLCO screen [5]. Participants were more likely to undergo a biopsy after a prostate specific antigen (PSA) value of > 7 ng/ml and after a positive digital rectal exam (DRE); a history of prostate problems and Asian ethnicity were also important correlates with adherence [5]. Men over the age of 70 were less likely to obtain a prostate biopsy when presented with a positive screening test in this study [5]. Moul noted that 55% of men with a positive PSA (> 4 ng/ml) had a biopsy within three years of the screening information; even with the highest risk category of PSA levels (PSA level > 10 ng/ml), only 75% obtained a biopsy by 3 years [6]. In a Veterans Administration clinic-based screening program for prostate cancer, Krongrad et al. reported that 57% of men with abnormal PSAs and/or DREs obtained a prostate biopsy [7]. These reports suggest that presentation of high risk status is not sufficient to guarantee that a man will obtain a prostate biopsy.

The current analysis expands the potential factors associated with adherence to an invasive EOS procedure that were previously identified using PCPT data [8, 9] by examining psychosocial outcomes, participant health status, participant adherence, and site characteristics. These factors were drawn from well-known health behavior models such as the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Health Belief Model.[10, 11] Identifying factors associated with potential non-adherence in a timely manner allows clinical trial researchers to select the population of participants most in need of an intervention to increase adherence. One year prior to the EOS biopsy coincides with a time when participants are close to the time of EOS biopsy, yet far enough out that an intervention strategy can be delivered and have sufficient time to work. This approach mimics the real world experiences of study staff working on clinical trials by only using information site staff have access to at the time the intervention strategy is applied.

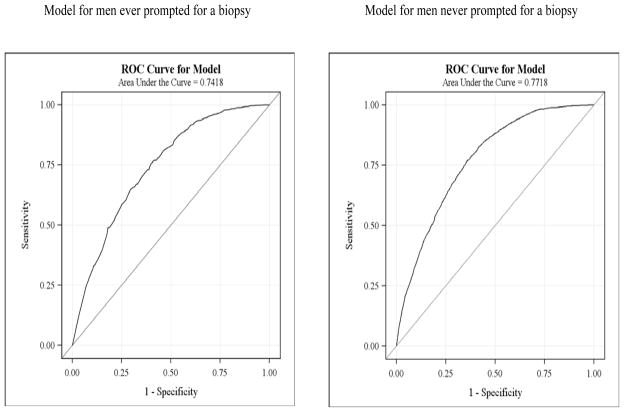

This study has two aims. The first is to investigate novel factors associated with adherence through multivariate logistic regression; the second is to use receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to compare the specificity and sensitivity of our model among men who were and were not prompted for a biopsy.

Materials and Methods

Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) Description

The PCPT was a 7-year randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the efficacy of finasteride for the prevention of prostate cancer [1, 12]. The primary outcome for the trial was prevalence of prostate cancer as measured by a transrectal ultrasonographic-guided biopsy of the prostate (minimum of six cores) at the end of 7 years or an interim diagnosis of prostate cancer. Men randomized to finasteride had a 24.8% reduction in the prevalence of prostate cancer compared to those who were randomized to placebo. Details of the trial design and eligibility criteria have been presented elsewhere [3, 13].

Criteria for Inclusion in the Biopsy Adherence Sample

This analysis examines factors associated with EOS biopsy adherence using information obtainable as of year 6, one year prior to the EOS biopsy. Participants who died or became lost to follow-up between years 6 and 7 (n=431) were included in the primary model and counted as having no EOS biopsy.

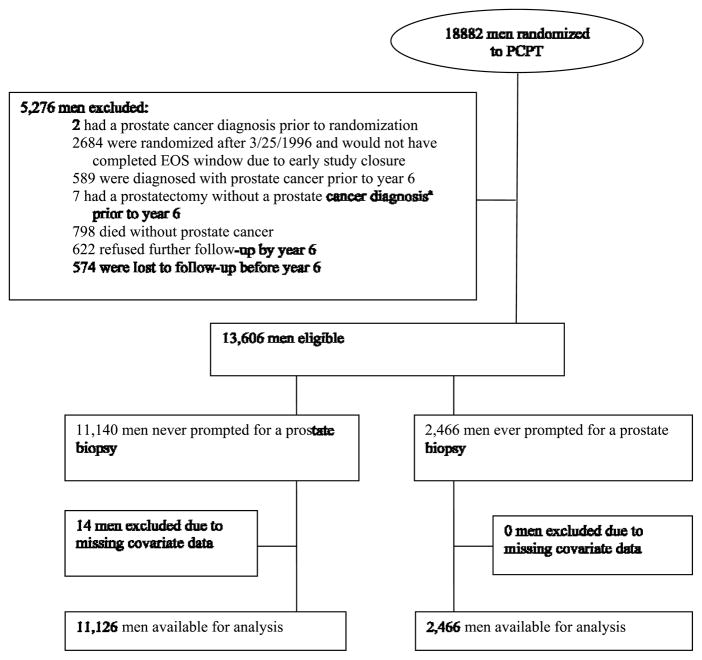

Eligibility and exclusion criteria are shown in Figure 1. Participants were eligible if none of the following events happened as of year 6: prostate cancer diagnosis; prostatectomy or cystoprostatectomy; death; loss to follow up. Participants randomized after March 26, 1996 were excluded due to early study closure on June 24, 2003; these participants did not complete their EOS windows (7-year anniversary of their randomization + 90 days) and their adherence could have been influenced by the early publication of study results. Missing demographic data on 14 participants led to their exclusion from these analyses.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram for PCPT analysis of factors associated with adherence to end-of-study biopsy

The analysis is stratified by biopsy prompt history: those participants who had ever been prompted for a prostate biopsy prior to year 6 (via elevated PSA or DRE suspicious for cancer) and those who had not, as these groups have potentially different motivations for adherence with the EOS biopsy.

Potential Covariates

The covariates considered for inclusion in the models are: age at year 6; demographics measured at randomization; comorbidities over the course of the trial; health related quality of life (HRQL) at year 6; measures of participant adherence at year 6; prior negative biopsy; and site characteristics. See Table 1 for a complete listing of covariates examined in this analysis.

Table 1.

Factors potentially associated with adherence to the end-of-study biopsy at year 7

| Covariate description |

|---|

| DEMOGRAPHIC |

| Age at year 6 |

| Race |

| Educationa |

| Marrieda |

| PROSTATE CANCER/CLINICAL HISTORY |

| Family history of prostate cancera |

| Everb had a negative prostate cancer biopsyc |

| Ever refused a biopsyc |

| PSA test and/or DRE done at year 6 |

| Had a biopsy prompt at year 6c |

| Refused a biopsy at year 6c |

| GENERAL ADHERENCE |

| Study drug adherence at year 6 |

| Ever missed a contact in the past year (between years 5 and 6) |

| Ever missed a contact between randomization and year 5 |

| Ever off treatment |

| COMORBIDITIES (staff interview) |

| Body mass index (BMI) (most recent available) |

| Ever reported benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) |

| Ever reported a cardiovascular event |

| Ever reported diabetes |

| Ever reported hypertension |

| HEALTH-RELATED QUALITY OF LIFEd from SF-36 (participant-reported) |

| General Health/Health Perception score |

| Physical Function score |

| Mental Health score |

| Vitality score |

| SITE CHARACTERISTICS |

| Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP) site |

| Randomized fewer than 200 participants |

| Poor performance |

| Ever received a retention and adherence (R&A) grant |

Abbreviations: DRE = digital rectal examination; PSA = prostate-specific antigen

At randomization

“Ever” indicates “ever prior to year 6” unless otherwise specified

Considered only for men who were ever prompted for a biopsy

At year 6

HRQL covariates were assessed using the Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36). SF-36 scales [14–16] are scored on a 0–100 scale with higher values reflecting better HRQL. Table 1 lists the four scales selected from the full SF-36 for this analysis, which cover key domains of HRQL. Participants who were off treatment were no longer required to submit HRQL forms. PCPT outcome and covariate measures for the HRQL component of the PCPT are described in Moinpour et al. [17] Participants with missing forms and participants with below average scores had similar odds ratios and were grouped and compared to participants with average or better scores. An “average or better” score is defined as a score that is equal to or greater than the population mean minus half a standard deviation (a moderate-sized effect) [18] for that particular score, based on the SF-36 scales for the US general population for men 55 and older [17]; these age-specific norms were provided for the PCPT by Dr. John Ware (Personal Communication, 1994) based on the normative database for the SF-36 published in the SF-36 Manual [19].

General adherence covariates measured how well a participant followed study protocol. Study drug administration was once daily; participants who stopped taking the study drug were considered off treatment. Adherence to this regimen was measured using pill counts and calculated as a percentage of required pills taken over time; at least 80% was considered adherent. Study contacts were quarterly, with visits every 6 months and phone calls at 3 months between visits. A participant who missed a regularly scheduled visit or call was counted as ever missing a visit. PSA tests and DREs were required annually with abnormal results prompting a biopsy. Participant refusal of a prompted biopsy by year 6 was considered a measure of non-adherence.

PCPT was conducted at 219 sites, with enrollment ranging from one (1) to 1444 randomized participants. Site characteristics included being an NCI-funded Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP) site [20], site performance, and receipt of a retention and adherence (R&A) grant. Site performance was measured by submission rate of study forms, with low submission rates indicating poor site performance. R&A grants were intended to support overall site retention and adherence activities. Additional adherence interventions are described in Table 2. Most of these activities were initiated midway through the trial, particularly after the conduct of a series of focus groups in which we examined barriers and reinforcements for complying with all trial requirements.

Table 2.

PCPT Biopsy Adherence Activities

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Biopsy Video: Your Prostate Biopsy: The Final Piece of the Puzzle | The PCPT Study Coordinator (IMT) introduced video, emphasizing how procedures will differ by PCPT site; a PCPT Urologist performed two for cause biopsies on patients (not study participants). The Study Coordinator describes the surgery as it is being performed (three components: digital rectal examination, probe and ultrasound, and the biopsy); explains what happens to the patient’s prostate tissue samples; describes what the patient should do after the biopsy (e.g., take prescribed antibiotic); two study participants comment on for cause biopsies they have experienced during the trial and the importance of the biopsy information for the trial. |

| Focus Group Project | Four groups held (San Antonio, TX and Winston-Salem, NC Showed video Identified participant barriers to complying with the endpoint biopsy Suggestions:

|

| Participant Feedback Post Viewing of Video | A list was posted at each PCPT site for participants to note comments about the prostate biopsy video. |

| Site Grants | Available for holding sessions to show the Biopsy Video, for Q&A sessions about the biopsy with study urologist. |

| Study Site Staff Meetings and Workshops | Reinforced the importance of the biopsy requirement and suggested strategies for preparing study participants (End of Study Biopsy Packet was distributed). Throughout the trial, site staff received current information on the progress of the study through the PCPT Newsletter, The PCPT update. |

| End-of-Study Biopsy Manual | This Manual was designed to help study staff educate study participants and site urologists about the importance of the end-of-study biopsy. It addressed the following planning issues: logistics (e.g., communicating with site urologists); holding a biopsy information session; biopsy information for study participants (e.g., the brochure); pathology issues; plans for after the biopsy; payment information for the biopsy; information on the site grant program; and tips for finding participants lost to follow-up. Site staff were encouraged to customize the folder to make it useful for the specific site but time tables and strategies were suggested. |

| Articles in the PCPT Participant (The Vanguard) & Staff Newsletters (PCPT update) |

|

| Endpoint Biopsy Brochure, Information Sheets | Your Prostate Biopsy: The Final Piece of the Puzzle Brochure allowed participants to have information about the end-of-study biopsy that they could take with them and share with family members and medical providers: how to prepare for the procedure; the three steps involved in the biopsy; what to expect after the biopsy; follow-up with physicians; receiving the biopsy results.. |

| Pilot Study at 1 Site | Held endpoint biopsy informational sessions for participants with study urologist and CRAs. Successful and not so successful strategies used in this pilot study were summarize for use in training workshops for all PCPT site staff. A Procedural Manual based on the pilot study was distributed to site staff. |

| Adherence Coordinator at Coordinating Center | This person (SH) supported a comprehensive set of adherence activities that included the endpoint biopsy requirement. |

Statistical Analysis

The probability of participants having an EOS biopsy versus non-adherence was modeled using logistic regression. Analyses used PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC in SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina) and accounted for participants clustered within sites.

Differences in descriptive study covariates were tested with the t-test and the chi-square test continuous and categorical measures, respectively. Collinearity diagnostics for multivariate models were performed on all candidate covariates, looking at variance inflation factor. Finally, potential interactions between site characteristics, general adherence and age were tested; statistically significant interactions were included in the final model. Multivariate models were conducted separately for men who received a biopsy prompt and men who did not.

Study covariates were chosen based on prior literature [8–11]; the final multivariate models included factors with significant bivariate relationships (Tables 1 and 3). In selecting these variables, we were aware of the interrelated nature of the many variables involved in encouraging study adherence.[21] For this analysis, therefore, we examined a full range of potential interactions between study participants, study staff, and investigators that might reinforce study bonding and enhance participant adherence to study requirements. Predictive power was measured using the area under the ROC curve, with a value ≥0.7 considered adequate discrimination. [22] All data were used to calculate ROC curves (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Characteristics of the subset of participants eligible for an end-of-study biopsy at year 6, stratified by whether or not they had the end-of-study biopsy

| Biopsied at year 7 (n = 8529) | Not biopsied (n = 5061) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEMOGRAPHICS | |||

| Age at year 6 | |||

| MEAN (SD) | 68.8 (5.4) | 69.6 (5.9) | <.0001 |

| <65 (n, %) | 2212 (25.9) | 1191 (23.5) | <.0001 |

| 65–69 (n, %) | 2733 (32.0) | 1504 (29.7) | |

| 70–75 (n, %) | 2203 (25.8) | 1292 (25.5) | |

| ≥75 (n, %) | 1381 (16.2) | 1074 (21.2) | |

| Race (n, %) | |||

| White | 7972 (93.5) | 4695 (92.8) | 0.0273 |

| Black | 258 (3.0) | 196 (3.9) | |

| Other | 299 (3.5) | 170 (3.4) | |

| Married as of randomization (n, %) | 7632 (89.5) | 4313 (85.2) | <.0001 |

| Education as of randomization (n, %) | |||

| High school diploma or less | 1517 (17.8) | 946 (18.7) | 0.3157 |

| Some college/vocational school | 2442 (28.6) | 1465 (28.9) | |

| College degree | 1441 (16.9) | 804 (15.9) | |

| Post-graduate degree | 3128 (36.7) | 1846 (36.5) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Family history of prostate cancer as of randomization (n, %) | 1387 (16.3) | 715 (14.1) | 0.0009 |

| GENERAL ADHERENCE | |||

| Adherent to study drug at year 6 (n, %) | 7181 (84.2) | 2374 (46.9) | <.0001 |

| DRE or PSA test done at year 6 (n, %) | 8397 (98.5) | 3804 (75.2) | <.0001 |

| No missed contacts before year 5 (n, %) | 5107 (59.9) | 1918 (37.9) | <.0001 |

| No missed contacts during the previous year (n, %) | 6839 (80.2) | 3231 (63.8) | <.0001 |

| Ever prompted for a biopsy (n, %) | 1661 (19.5) | 803 (15.9) | <.0001 |

| Ever refused a biopsy (n, %) | 927 (10.9) | 500 (9.9) | 0.0689 |

| Ever had a negative biopsy (n, %) | 1034 (12.1) | 431 (8.5) | <.0001 |

| COMORBIDITIES | |||

| No history of cardiovascular events (n, %) | 6084 (71.3) | 3410 (67.4) | <.0001 |

| No history of diabetes (n, %) | 7822 (91.7) | 4609 (91.1) | 0.1954 |

| Last available body mass index (BMI) | |||

| MEAN (SD) | 27.4 (4.2) | 27.4 (4.5) | 0.5811 |

| Normal (<25) (n, %) | 2156 (25.3) | 1324 (26.2) | 0.6709 |

| Overweight (25–29) (n, %) | 4155 (48.7) | 2418 (47.8) | |

| Obese (≥30) (n, %) | 2142 (25.1) | 1274 (25.2) | |

| Missing (n, %) | 76 (0.9) | 45 (0.9) | |

| Smoking status as of randomization (n, %) | |||

| Never | 2925 (34.3) | 1592 (31.5) | 0.0001 |

| Current | 576 (6.8) | 414 (8.2) | |

| Former | 5028 (59.0) | 3054 (60.3) | |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | |

| HEALTH-RELATED QUALITY OF LIFE AT YEAR 6 | |||

| Vitality score | |||

| MEAN (SD) | 69.5 (17.2) | 65.8 (19.9) | <.0001 |

| Average or better (n, %) | 6783 (79.5) | 2404 (47.5) | <.0001 |

| Below average (n, %) | 832 (9.8) | 516 (10.2) | |

| Missing form (n, %) | 914 (10.7) | 2141 (42.3) | |

| Physical Functioning score | |||

| MEAN (SD) | 83.3 (19.5) | 78.2 (23.9) | <.0001 |

| Average or better (n, %) | 6779 (79.5) | 2382 (47.1) | <.0001 |

| Below average (n, %) | 857 (10.0) | 545 (10.8) | |

| Missing form (n, %) | 893 (10.5) | 2134 (42.2) | |

| General Health score | |||

| MEAN (SD) | 77.2 (16.2) | 73.2 (18.8) | <.0001 |

| Average or better (n, %) | 7118 (83.5) | 2535 (50.1) | <.0001 |

| Below average (n, %) | 515 (6.0) | 394 (7.8) | |

| Missing form (n, %) | 896 (10.5) | 2132 (42.1) | |

| Mental Health score | |||

| MEAN (SD) | 84.8 (12.3) | 82.0 (14.4) | <.0001 |

| Average or better (n, %) | 6722 (78.8) | 2394 (47.3) | <.0001 |

| Below average (n, %) | 891 (10.4) | 528 (10.4) | |

| Missing form (n, %) | 916 (10.7) | 2139 (42.3) | |

| SITE CHARACTERISTICS | |||

| Ever received a recruitment and adherence grant (n, %) | 6318 (74.1) | 3049 (60.2) | <.0001 |

| Number of participants randomized at site (n, %) | |||

| ≤200 | 4581 (53.7) | 3434 (67.9) | <.0001 |

| >200 | 3948 (46.3) | 1627 (32.1) | |

| Poorly performing site (n, %) | 734 (8.6) | 835 (16.5) | <.0001 |

| Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP) (n, %) | 2835 (33.2) | 1570 (31.0) | 0.0076 |

P-values are from t-tests (comparison of means) and χ2 tests (comparison of categorical distributions)

Abbreviations: DRE = digital rectal examination; PSA = prostate specific antigen

Figure 2.

ROC curves for multivariate logistic regression model stratified by biopsy prompt status

Results

Descriptive Findings

Excluded participants were less likely to be white (88% vs. 93%) or be from a larger site (33% vs. 41%). Differences were greater for participants lost to follow-up than participants excluded due to early study closure. Participants who had ever received a biopsy prompt by year 6 were more likely to have an EOS biopsy than those who had not received a prompt (unadjusted OR=1.28[95% CI=1.17,1.41]). The EOS biopsy rate among men ever and never prompted for a biopsy was 67.4% and 61.7%, respectively. The combined EOS biopsy rate for all participants included in this analysis was 62.8%.

Table 3 provides descriptive information for participants by EOS biopsy adherence status. Participants who had an EOS biopsy were different from participants who did not have the procedure. Participants who obtained biopsies were more likely to be adherent to study drug at year 6 (84.2% vs. 46.9%) or have a DRE or PSA test at year 6 (98.5% vs. 75.2%). They were more likely to come from sites that were larger, received R&A grants, or were performing well. Differences for most characteristics presented in Table 3 are not very sizeable, in spite of the small p-values.

Models

Table 4 presents the final model and odds ratios for having an EOS biopsy for the subset of men who ever had a biopsy prompt by year 6. Main effects show that participants were more likely to adhere to the EOS biopsy if they were adherent to study visit schedules and procedures (adherent to study drug, had DRE/PSA test, no missed contacts) and/or were in good health (younger age, high/better SF-36 Physical Functioning scores). The SF-36 Mental Health score was identified as being collinear with the other HRQL measures and was excluded from the analyses presented in Tables 4 and 5. Interaction results showed participants at larger sites that received R&A grants were more likely to have an EOS biopsy.

Table 4.

Odds ratios for end-of-study biopsy adherence for men ever prompted for a biopsy

| n=2466 at risk, n=1662 events | ||

|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Model 1 | ||

| DEMOGRAPHICS | ||

| Age ≤ 70a at year 6 | 1.39 (1.15, 1.67) | 0.0008 |

| GENERAL ADHERENCE | ||

| Adherent to study drug at year 6 | 2.29 (1.80, 2.91) | <.0001 |

| DRE or PSA test done at year 6 | 5.28 (2.88, 9.65) | <.0001 |

| No missed contacts before year 5 | 1.35 (1.09, 1.66) | 0.0053 |

| No missed contacts during the previous year | 1.47 (1.08, 2.00) | 0.0146 |

| HEALTH-RELATED QUALITY OF LIFE AT YEAR 6 | ||

| Physical Functioning score average or better | 1.67 (1.33, 2.09) | <.0001 |

| SITE CHARACTERISTICS | ||

| Ever received an R&A grant | 1.80 (1.27, 2.55) | 0.0009 |

| ≤200 participants randomized at site | 0.71 (0.50, 1.01) | 0.0601 |

| Model 2 | ||

| Site sizeb and receipt of R&A grant | ||

| Smaller site, received an R&A grant | 2.36 (0.83, 6.67) | 0.1057 |

| Smaller site, no R&A grant | 1.50 (0.53, 4.21) | 0.4417 |

| Larger site, received an R&A grant | 3.81 (1.35, 10.70) | 0.0113 |

| Larger site, no R&A grant | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Model 3 | ||

| Site sizeb and PSA/DRE test at year 6 | ||

| Smaller site, participant had DRE/PSA | 5.42 (2.10, 14.03) | 0.0005 |

| Smaller site, participant had no DRE/PSA | 1.42 (0.49, 4.14) | 0.5234 |

| Larger site, participant had DRE/PSA | 7.88 (3.18, 19.55) | <.0001 |

| Larger site, participant had no DRE/PSA | 1.00 (reference) | |

Interactions obtained by adding each one separately to the main effects model. Model 1 contains only the main effects, Model 2 contains the main effects and the site size/R&A grant interaction, and Model 3 contains the main effects and the site size/DRE and PSA tests interaction.

Median age at year 6 for this group

Site size is defined as smaller (≤200 participants registered) or larger (> 200 participants registered)

Abbreviations: DRE = digital rectal examination; PSA = prostate specific antigen; R&A = retention and adherence

Table 5.

Odds ratios for end-of-study biopsy adherence for men never prompted for a biopsy

| n=11126 at risk, n=6868 events | ||

|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Model 1 | ||

| DEMOGRAPHICS | ||

| Age ≤ 68a at year 6 | 1.19 (1.08, 1.31) | 0.0005 |

| Married | 1.32 (1.14, 1.53) | 0.0002 |

| GENERAL ADHERENCE | ||

| Adherent to study drug at year 6 | 2.75 (2.38, 3.18) | <.0001 |

| DRE or PSA test done at year 6 | 5.61 (4.18, 7.53) | <.0001 |

| No missed contacts before year 5 | 1.37 (1.19, 1.58) | <.0001 |

| No missed contacts during the previous year | 1.25 (1.03, 1.53) | 0.0234 |

| COMORBIDITIES | ||

| No history of cardiovascular events before year 6 | 1.35 (1.19, 1.52) | <.0001 |

| HEALTH-RELATED QUALITY OF LIFE AT YEAR 6 | ||

| General Health/Health Perception score average or better | 1.62 (1.40, 1.87) | <.0001 |

| SITE CHARACTERISTICS | ||

| Ever received an R&A grant | 1.29 (0.98, 1.71) | 0.0730 |

| ≤200 participants randomized at site | 0.63 (0.47, 0.84) | 0.0016 |

| Poorly performing site | 0.66 (0.46, 0.96) | 0.0300 |

| Model 2 | ||

| Site sizeb and receipt of R&A grant | ||

| Smaller site, received an R&A grant | 1.49 (1.15, 1.94) | 0.0030 |

| Smaller site, no R&A grant | 1.32 (1.03, 1.69) | 0.0288 |

| Larger site, received an R&A grant | 2.69 (2.10, 3.45) | <.0001 |

| Larger site, no R&A grant | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Model 3 | ||

| Age at year 6c and site performance | 0.70 (0.46, 1.06) | 0.0941 |

| Younger participant, poor site performance | 1.24 (1.12, 1.37) | <.0001 |

| Younger participant, acceptable site performance | 0.79 (0.57, 1.10) | 0.1679 |

| Older participant, poor site performance | ||

| Older participant, acceptable site performance | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Model 4 | ||

| Age and adherence to study drug, at year 6 | ||

| Younger participant, adherent | 3.34 (2.77, 4.03) | <.0001 |

| Younger participant, not adherent | 1.28 (1.09, 1.51) | 0.0028 |

| Older participant, adherent | 2.91 (2.43, 3.50) | <.0001 |

| Older participant, not adherent | 1.00 (reference) | |

Interactions obtained by adding each one separately to the main effects model. Model 1 contains only the main effects, Model 2 contains the main effects and the site size/R&A grant interaction, Model 3 contains the main effects and the age/site performance interaction, and Model 4 contains the main effects and the age/study drug adherence interaction.

Median age at year 6 for this group

Site size is defined as smaller (≤200 participants registered) or larger (> 200 participants registered)

Age is defined as younger (≤ 68) and older (> 68)

Abbreviations: DRE = digital rectal examination; PSA = prostate specific antigen; R&A = retention and adherence

As shown in Table 5, the subset of participants never prompted for a biopsy by year 6 also were more likely to adhere to the EOS biopsy if they were adherent to study visit schedules and procedures and/or were in good health (high/better SF-36 General Health/Health Perceptions scores). Interaction results showed participants at larger sites that received R&A grants also were more likely to have an EOS biopsy.

ROC curves for each model are shown in Figure 2. The models have adequate discrimination between men who will and will not receive an EOS biopsy; the area under the ROC curve for men ever and never prompted for a biopsy is 0.74 (95% CI=0.72,0.76) and 0.77 (95% CI=0.76,0.78), respectively.

Site size has a modest impact on the variability of EOS biopsy adherence. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for site size and EOS biopsy adherence among men ever prompted for a biopsy is 0.11 (0.11 for small sites; 0.07 for large sites). Among men never prompted for a biopsy ICC=0.08 (0.08 for small sites; 0.05 for large sites).

Discussion

The goal of this research was to identify factors prospectively associated with the EOS biopsy in the PCPT. More specifically, we sought to determine which factors identifiable at year 6 were associated with a participant’s willingness to undergo an invasive procedure one year later. The PCPT is unique because it was a prevention, rather than a treatment, trial: the biopsy procedure was critical for evaluating the intervention, but not clinically indicated for most participants. A recent study examining the use of research biopsies in therapeutic clinical trials shows that participants may not have a clear understanding of the risks and benefits of these procedures, suggesting that researchers need to improve study protocols and informed consents to ensure that participants fully understand the study procedures and requirements.[23] This is particularly important in trials like the PCPT where the EOS biopsy happens 7 years after participant enrollment.

Interpretation of Results

Our results show that a variety of participant and site characteristics are associated with participant adherence to the invasive EOS requirement. At the participant level, adherence with study schedule and procedures and general good health is associated with higher EOS biopsy rates; participants at sites that were larger and/or procured R&A grants also had higher EOS biopsy rates.

Probstfield and colleagues have identified failing to adhere to the study agent regimen, missing a study visit, and going off study treatment as “red flags” [24, 25] that should be addressed during the course of the trial to keep participants fully engaged in trial activities and outcomes ascertainment.

These “red flags” coincide with the general adherence factors identified in this analysis as being associated with EOS biopsy adherence. While the analysis does not indicate that improving adherence to study requirements will improve adherence to the EOS biopsy, it does lend support to their status as “red flags.”

Our study found that older men were less adherent, as did the PLCO for any diagnostic procedure [5]. In the PCPT, the lower EOS biopsy adherence rate for older participants could be related to the perceived physical demands of the procedure or age-related medical contraindications. For example, one of the reasons physicians recommended that participants not obtain the EOS biopsy was the need to stop anticoagulation medication for this study-specific procedure. It is important to note that these physicians were not associated with the study, so their primary concern was the well-being of their patients.

We expect larger sites to perform better in nearly all aspects of the study, including having higher rates of EOS biopsies, primarily due to economy of scale. Successful large sites require better management practices to be efficient. Smaller sites can tolerate inefficiencies better and, due to small volume, may lack the motivation to streamline study practices. For example, the top accruing PCPT site had 1444 participants, nearly three times the next largest site, and was considered one of PCPT’s best sites for data quality. The finding regarding R&A grants is ambiguous. We cannot determine from this analysis whether site use of R&A grants specifically affected EOS biopsy rates, or if there is something different about the sites that applied for and received the R&A grants.

The primary concern of this analysis is correctly identifying participants at risk of not completing final study requirements. Identifying these participants shortly before the final study outcome assessment and targeting them with intervention strategies to increase adherence with final study requirements may be a better use of limited staff time than strategies directed at all participants throughout the trial. The cost of any strategies and the cost of identifying the appropriate participants, however, must be weighed against the benefit to the study. If the study design assumptions are not being met and the ability of the study to achieve its objectives is at risk, an intervention strategy may be worthwhile to salvage the study. In the case of the PCPT, we conducted a number of adherence activities to help site staff and participants recognize the importance of the end-of-study biopsy. These initiatives were not formally evaluated although we solicited and received feedback from site staff and study participants on their reaction to most of these activities; this feedback was helpful each time and helped inform the next set of activities.

PCPT met its study specified biopsy rate of 60%, which implies reasonable adherence because the study design required a 60% rate ascertainment of prostate cancer status. Interventions were suggested to all PCPT sites for enhancing adherence with the EOS biopsy because this was an invasive trial outcome. As noted in Table 2, we held EOS informational/educational sessions with participants (often funded with an R&A grant), asked sites to show the EOS Biopsy video distributed to all PCPT sites at the educational session and making it accessible to participants whenever they were at the site, distributed the EOS Biopsy brochure to all participants, and provided the EOS Biopsy Manual to be used by site staff to ready each site and its participants for this challenging outcome.

Limitations

The study population was mostly white, highly educated, and healthy; the results may not be applicable to more diverse and underserved populations. To obtain the PCPT prostate biopsy endpoint, the study required a participant commitment of 7 years, and the models apply only to participants who remained in the study for at least 6 years.

Conclusions

A variety of factors are prospectively associated with complying with the EOS biopsy: adherence to basic requirements for research study participation, good participant health, and certain site characteristics. This model is perhaps best used as a starting point for other studies to consider when trying to increase adherence to invasive, non-clinically indicated procedures. These factors can be used to identify a subgroup of trial participants who are not likely to have a non-clinically indicated procedure. The study can then apply an appropriate intervention strategy to increase adherence to that procedure.

We conclude with a quotation from a PCPT participant who agreed to be in one of the focus groups held midway through the 7-year study period. The question was raised about the impact of any problems experienced with the study drug. One participant who indicated some problems with the drug said, “…but dropping out would be like jumping ship. All that time would be wasted.” The facilitator asked him, “For you or the study?” and the participant responded, “Well, for me and the study because I am the study.” Our ability to carry out successful long-term prevention trials is certainly enhanced if we can create a study environment that generates this level of participant commitment.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the many men in the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial who participated for the seven years of the trial. In addition, we thank the physicians, nurses, and Clinical Research Associates who recruited participants for the trial and successfully followed them for the seven-year period.

PCPT Recruitment and Adherence Committee Members:

Otis Brawley, MD

Susie Carlin, BA

Dee Daniel

Edward DeAntoni, PhD (Co-Chair with Dr. Gritz for several years)

Patricia Ganz, MD

Ellen R. Gritz, PhD (Chair)

Carolyn Harvey, PHD

M Shannon Hill, BM

Lori Minasian, MD

Carol M. Moinpour, PhD

Rose Mary Padberg, RN, MA

Jeanne Parzuchowski, RN, MS

Jeffrey Probstfield, MD

Anne Ryan, RN

Connie Szczepanek, RN, BSN

Sarah Moody Thomas, PhD

Ian Thompson, MD

Clarence Vaughn, MD

This research was supported by Public Health Service grant number CA37429 (C.D. Blanke [C.A. Coltman]) from the Department of Cancer Prevention, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, MD. The study agents (finasteride and placebo) were provided by Merck, Inc. Merck, Inc. and the National Cancer Institute (NCI), Division of Cancer Prevention (DCP) also provided funding to produce videos and to support projects to enhance trial recruitment and adherence. The content of this work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Ellen Gritz was supported in part by funding from the National Cancer Institute, P30CA16672 (R.A. DePinho).

Abbreviations

- CCOP

Community Clinical Oncology Program

- DRE

digital rectal exam

- EOS

end-of-study

- HRQL

health-related quality of life

- ICC

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- PCPT

Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial

- PLCO

Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial

- PSA

prostate specific antigen

- R&A

recruitment and adherence

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- SF-36

Short Form-36 Health Survey

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The PCPT [1] was a 7-year randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the efficacy of finasteride for the prevention of prostate cancer. This research was supported by Public Health Service grant number CA37429 (C.D. Blanke [C.A. Coltman]) from the Department of Cancer Prevention, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, MD. The study agents (finasteride and placebo) were provided by Merck, Inc. Merck, Inc. and the National Cancer Institute (NCI), Division of Cancer Prevention (DCP) also provided funding to produce videos and to support projects to enhance trial recruitment and adherence. The content of this work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute. Phase III Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Finasteride (Proscar) for the Chemoprevention of Prostate Cancer. Clinical Trials (PDQ) [cited January 25, 2011]; Available from: http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/search/view?cdrid=78498&version=healthprofessional.

- 2.Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence (review) Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2008:Article number CD000011. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiegl P, Blumenstein B, Thompson I, et al. Design of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) Controlled Clinical Trials. 1995;16:150–63. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(94)00xxx-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor KL, Shelby R, Gelmann E, McGuire C. Quality of life and trial adherence among participants in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1083–94. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinsky PF, Andriole GL, Kramer BS, et al. Prostate biopsy following a postive screen in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial. J Urol. 2005;173:746–51. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000152697.25708.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moul JW. Editorial comment on Prostate biopsy following a positive screen in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian cancer screening trial. J Urol. 2005;173:750. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000152697.25708.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krongrad A, Kim CO, Jr, Burke MA, Granville LJ. Not all patients pursue prostate biopsy after abnormal prostate specific antigen results. Urol Oncol. 1996;2:35–9. doi: 10.1016/1078-1439(96)00038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Redman MW, Tangen CM, Goodman PJ, et al. Finasteride does not increase the risk of high-grade prostate cancer: A bias-adjusted modeling approach. Cancer Prev Res. 2008;1:174–81. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson IM. Editorial comments on Reduction in the risk of prostate cancer: Future directions after the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. Urology. 2010;75:509–10. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.05.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azjen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Beh Hum Dec. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abraham C, Sheeran P. The health belief model. In: Conner M, Norman P, editors. Predicting Health Behaviour: Research and Practice with Social Cognitive Models. 2. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson IM, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. The influence of finasteride on the development of prostate cancer. New Engl J Med. 2003;349:213–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, Crowley JJ, et al. Implementation of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) Control Clin Trials. 2004;25:203–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Lu JFR, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32:40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–63. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moinpour CM, Lovato LC, Thompson IM, Jr, et al. Profile of men randomized to the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial: Baseline health-related quality of life, urinary and sexual functioning, and health behaviors. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1942–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.9.1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware JE, Jr, Snow KK, Kosinski MA, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and interpretation guide. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minasian L, Carpenter W, Weiner B, et al. Translating research into evidence-based practice: the National Cancer Institute Community Clinical Oncology Program. Cancer. 2010;116:4440–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowen D, Moinpour C, Thompson B, et al. Creation of a public health framework for public health intervention design. In: Miller S, Bowen D, Croyle R, Rowland J, editors. Handbook of cancer control and behavioral science. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. pp. 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2. New York: Wiley, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Overman MJ, Modak J, Kopetz S, et al. Use of research biopsies in clinical trials: Are risks and benefits adequately discussed? J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:17–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Probstfield JL, Russell ML, Henske JC, et al. Successful program for recovery of dropouts to a clinical trial. Am J Med. 1986;80:777–84. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90615-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Probstfield JL, Russell ML, Insull W, Jr, Yusuf S. Dropouts from a clinical trial, their recovery and characterization: A basis for dropout management and prevention. In: Shumaker SA, Schron EB, Ockene JK, editors. The Handbook of Health Behavior Change. New York: Springer; 1990. pp. 376–400. [Google Scholar]